Abstract

Background: Sleep care is crucial for the health and development of infants, with proper sleep patterns reducing the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and other sleep-related incidents. Educational interventions targeting caregivers are essential in promoting safe sleep practices. Methods: This systematic review adhered to PRISMA guidelines, searching databases such as PubMed, MEDLINE, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library. Inclusion criteria focused on studies involving home-based interventions for infants aged 0–12 months, including parental education and behavioral interventions. Exclusion criteria included studies in clinical settings and non-peer-reviewed articles. Data extraction and synthesis were performed by two independent reviewers, using a narrative approach to categorize interventions and outcomes. Results: Twenty-three studies met the inclusion criteria. Key findings indicate that home-based educational interventions, including hospital-based programs, home visits, and mobile health technologies, significantly improve parental knowledge and adherence to safe sleep practices. These interventions also enhance parental satisfaction and contribute positively to infant health outcomes. Conclusions: Educational interventions have demonstrated effectiveness in promoting safe sleep practices among caregivers, particularly in home settings. These interventions, including hospital-based programs, home visits, and digital tools, improve parental knowledge, adherence to guidelines, and overall satisfaction. The impact is evident in the reduction of unsafe sleep behaviors and enhanced infant health outcomes. However, variability in the intervention methods and delivery, cultural contexts, and geographic focus suggest a need for more tailored, long-term, and comprehensive studies. Future research should standardize outcome measures and assess the sustained impact of these educational strategies on infant sleep patterns and caregiver practices over time. This will provide deeper insights into the trends and long-term effectiveness of educational patterns and methods in diverse home environments.

1. Introduction

Sleep care is a critical aspect of infant health, directly influencing growth, development, and overall well-being. Establishing appropriate sleep patterns in neonates is pivotal in their physical and cognitive development, serving as a cornerstone for healthy developmental trajectories. Conversely, sleep disturbances in this age group can lead to significant challenges, impacting both the infant and the family. Poor sleep can affect an infant’s immune function, mood regulation, and cognitive processes while also contributing to parental stress and fatigue, potentially impairing the caregiver’s ability to provide optimal care [1].

Educational interventions targeting parents and caregivers are instrumental in promoting optimal sleep patterns in neonates. These interventions frequently encompass hospital-based education, home visiting programs, and parental workshops designed to promote safe sleep practices, establish consistent sleep routines, and mitigate the risk of sleep-related incidents such as sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) [2]. The effectiveness of these interventions varies, influenced by factors such as the delivery method, cultural considerations, and the specific needs of the family [3].

Hospital-based educational programs have shown significant improvements in parental knowledge and adherence to safe sleep practices, reducing the incidence of SIDS and promoting safer sleep environments for infants [1]. Personalized education and support are hallmarks of home visiting programs, which address specific concerns and cultural practices influencing compliance with safe sleep recommendations [2]. Parental workshops provide interactive sessions where caregivers can engage with experts, discuss challenges, and receive practical advice on implementing safe sleep practices [4]. A previous review focused on high-risk populations, finding that traditional safer sleep messaging may be less effective for vulnerable groups, advocating for more tailored interventions that address not only knowledge but also behavioral change components such as parental motivation and environmental factors [5]. Additionally, a recent systematic review protocol [6] aims to evaluate the effectiveness of preventive parental education from pregnancy to 1 month postpartum, focusing on infant sleep patterns, parental sleep, and postpartum depression. These reviews highlight key gaps in existing strategies, particularly for high-risk groups and early intervention periods [6].

This systematic review aims to evaluate the trends, effectiveness, and impact of educational patterns and methods within home settings on infant’s sleep. By analyzing a wide range of studies, this review seeks to identify the most effective strategies for improving sleep duration, reducing night awakenings, enhancing parental satisfaction, and promoting overall infant health. Our review adds to this body of knowledge by providing a comprehensive evaluation of educational strategies across the broader population, identifying effective methods and areas for improvement in promoting safe infant sleep practices.

The focus on “home settings” in this investigation is crucial because the majority of infant sleep-related incidents, including SIDS, occur in the home, making it the most relevant environment for intervention. Home settings offer unique challenges compared to clinical environments, as caregivers are responsible for implementing safe sleep practices without direct oversight from healthcare professionals. Educational interventions within homes, such as personalized counseling, home visits, and digital health tools, are designed to address the specific socio-cultural and economic factors that influence caregiver behavior. These interventions allow for practical, sustainable improvements in infant sleep practices in real-world contexts, particularly benefiting underserved populations. By focusing on home-based care, this study fills a gap in the literature, as many previous studies have concentrated on clinical settings, offering insights into how educational strategies can be most effective where they are most needed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

We conducted a comprehensive literature search in line with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [7] across multiple databases, including PubMed, MEDLINE, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library. The search strategy incorporated a combination of keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms related to infant’s sleep, education, home care, and effectiveness. The search terms used were: “neonatal sleep”, “infant sleep”, “newborn sleep”, “parental education”, “parental training”, “parental intervention”, “home care”, “home-based care”, “domestic care”, “effectiveness”, “outcome”, “impact”, “safe sleep practices”, “SIDS prevention”, and “sleep safety”.

Boolean operators (AND, OR) were utilized to combine search terms and refine results. We applied filters to include only studies published in peer-reviewed journals published until 20 October 2024. We also hand-searched the reference lists of relevant articles to identify additional studies. A comprehensive literature search strategy is provided in Supplementary File S2. Our review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under identification number CRD42024581176.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria for this review were as follows:

- Studies published in peer-reviewed journals.

- Studies focusing on infants (aged 0–12 months).

- Interventions implemented in home settings, such as parental education, behavioral interventions, and the use of mobile health technologies.

- Measured outcomes, including sleep patterns (e.g., adherence to safe sleep practices), parental satisfaction (e.g., satisfaction with the intervention, confidence in managing sleep), and infant’s and parents’ well-being (e.g., sleep duration, depression)

- Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods research designs.

- Studies available in English.

The exclusion criteria included the following:

- Studies not published in peer-reviewed journals.

- Studies conducted in clinical or institutional settings, such as hospitals or neonatal intensive care units (NICUs).

- Articles not available in English.

- Case reports, commentaries, and editorials.

2.3. Quality Assessment

A comprehensive quality assessment was conducted for the included studies using appropriate tools based on their respective study designs. Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) were assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (RoB 2) [8], which evaluates biases in randomization, allocation, blinding, and outcome reporting. For longitudinal and cohort studies, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Quality Assessment Tool [9] and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [10] were employed to evaluate factors such as selection bias, outcome assessment, and follow-up adequacy. Cross-sectional studies were appraised using the Appraisal Tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS) Tool [11], while quality improvement projects were assessed using the Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) Guidelines [12]. Quasi-experimental studies were evaluated using the Risk of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool [13], focusing on biases arising from non-random allocation. Single-arm feasibility studies were appraised using the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Feasibility and Pilot Study Risk of Bias Tool [14]. This systematic approach ensured that each study’s methodological quality was rigorously evaluated, providing confidence in synthesizing findings and minimizing potential biases’ impact. The results of Quality Assessment are available in Supplementary File S3.

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two independent reviewers conducted data extraction using a standardized form. The data extraction form included the following elements:

- Study design (e.g., randomized controlled trial, cohort study, qualitative study).

- Sample size and characteristics (e.g., number of participants).

- Intervention details (e.g., type of intervention, duration, delivery method).

- Outcome measures (e.g., sleep patterns, parental satisfaction, infant and parental well-being).

- Key findings and conclusions.

Any discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer. Extracted data were synthesized using a narrative approach, categorizing results by type of intervention (e.g., educational programs, behavioral interventions, mobile health interventions) and outcomes (e.g., sleep patterns, parental satisfaction, effects on parental and infant well-being). This allowed for a comprehensive summary of the evidence, highlighting similarities and differences across studies, identifying patterns, and drawing conclusions about the effectiveness of various interventions.

2.5. Study Selection Process

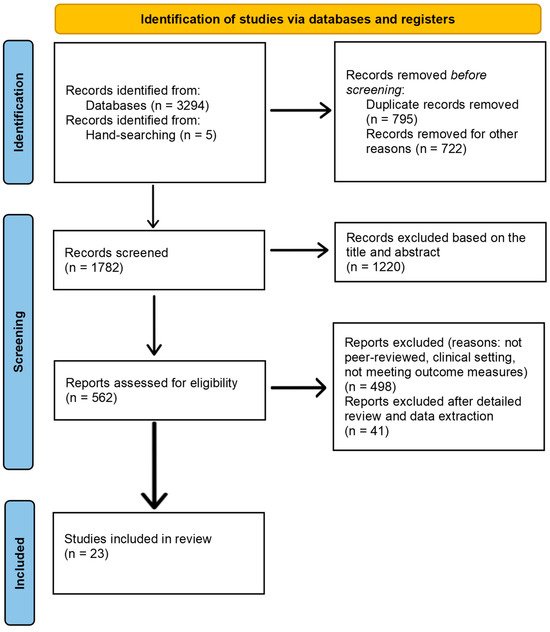

Identification:

- Databases searched: PubMed, MEDLINE, Scopus, Cochrane Library.

- A total of 3294 records were identified through database searches.

- Duplicate records removed: 795.

- Records removed for other reasons: 722.

- Additional records identified through hand-searching of reference lists: 5.

Screening:

- Evaluation of 1782 articles.

- Titles and abstracts screened for relevance.

- 1220 articles excluded based on title and abstract.

- 562 full-text articles assessed for eligibility.

Eligibility:

- Full-text articles reviewed against inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- 498 articles excluded (reasons: not peer-reviewed, clinical setting, not meeting outcome measures).

Included:

- 64 articles met inclusion criteria after full-text review.

- Final selection: 23 studies were included in the systematic review after detailed review and data extraction.

The PRISMA flow diagram for this study selection process is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

3. Results

3.1. Included Studies

The final set of 23 studies included in the systematic review provides robust evidence to evaluate the effectiveness of home-based interventions aimed at improving infant sleep patterns, enhancing parental satisfaction, and promoting infant health.

Table 1 summarizes the studies included in the systematic review [1,2,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

Table 1.

Summary of studies included.

3.2. Trends in Educational Interventions

The review identified several trends in educational interventions for infant sleep care. Common strategies included parental education programs, digital health interventions, and personalized counseling. Hospital-based educational programs and comprehensive hospital initiatives have shown significant improvements in parental knowledge and adherence to safe sleep practices [1,17,24]. The integration of technology, such as mobile apps and online resources, has become increasingly prevalent, providing accessible and scalable solutions for parental education [22,25,26]. Moreover, home-visiting programs and community-based initiatives offer personalized education and support, addressing specific concerns and cultural practices that influence safe sleep adherence [27,29,33]. These diverse approaches highlight the importance of multifaceted interventions tailored to the unique needs of families to effectively promote safe sleep practices and improve infant health outcomes. It has been suggested that combining different educational interventions, such as hospital-based education with follow-up home visits or digital tools, leads to improved adherence to safe sleep practices and better infant health outcomes. For example, Moon et al. [24] found that combining mobile health interventions with nursing quality improvement programs resulted in significantly higher adherence to safe sleep guidelines than when these interventions were used alone. Similarly, interventions that include both in-person education and digital reminders demonstrate better parental adherence and knowledge retention compared to single-method approaches [24].

3.3. Effectiveness of Educational Strategies

The review of various studies highlights the effectiveness of different educational strategies in improving infants’ sleep care. These strategies have shown varying degrees of success in enhancing parental knowledge and adherence to safe sleep practices.

Several studies have demonstrated that combined educational interventions are more successful in enhancing parental knowledge and adherence to safe sleep practices. For example, hospital-based education combined with home visits or mobile health technologies have shown significant improvements in safe sleep adherence. Moon et al. [24] found that the combination of a mobile health intervention with nursing quality improvement programs led to higher adherence to safe sleep practices compared to using these interventions separately. Similarly, the study by McDonald et al. [21] highlighted the effectiveness of structured educational sessions delivered during well-child visits, which significantly improved adherence to all key safe sleep practices. These findings suggest that multifaceted approaches involving continuous reinforcement, such as combining in-person education with digital tools, are more effective than single-method interventions.

Targeted interventions and continuous follow-up have proven to be highly effective. For instance, Brashears et al. [16] enhanced screening and education by incorporating specific sleep safety questions and providing targeted education during well-child visits. This approach led to a significant reduction in unsafe sleep practices, highlighting the importance of ongoing education to ensure adherence to safe sleep guidelines. Similarly, hospital-based programs also play a crucial role in providing foundational knowledge. Goodstein et al. [1] demonstrated that a comprehensive hospital-based infant sleep safety program significantly improved parental adherence to sleep safety practices, with high retention of correct supine sleeping knowledge at follow-up, stressing the critical role of intensive, early hospital education.

In addition to in-person education, long-term parental education has shown sustained benefits in maintaining safe sleep environments. Mathews et al. [15] conducted a longitudinal cohort study, finding that continuous education reduced the use of soft bedding and improved safe sleep practices over time. This suggests that long-term parental education is key to ensuring adherence to sleep safety practices as infants grow.

Early educational interventions delivered shortly after birth further enhance knowledge and adherence. McDonald et al. [23] evaluated a randomized controlled trial where safe sleep health education was provided at a 2-week well-child visit. This early intervention significantly improved parents’ understanding and practice of safe sleep behaviors, underscoring the need to engage parents early in the postpartum period.

Mobile health interventions have emerged as effective tools in promoting safe sleep practices, particularly when combined with other strategies. Moon et al. [24] found that mobile health interventions significantly improved adherence to safe sleep guidelines, whereas a nursing quality improvement program alone did not yield the same results, highlighting the potential of digital platforms to reinforce education. Moreover, Moon et al. [25] identified that mobile health interventions influenced maternal attitudes and social norms, leading to higher adherence to safe sleep practices like supine sleep positioning and room-sharing without bed-sharing. These findings emphasize the importance of addressing not just knowledge but also attitudes and behaviors through accessible digital tools.

Finally, tailored and community-based interventions also play a crucial role. Thompson et al. [32], in the “Delta Healthy Sprouts” study, highlighted that tailored educational interventions addressing both infant sleep and activity led to improvements in maternal knowledge and adherence to sleep duration recommendations. However, some gaps, such as knowledge about tummy time, remain, indicating a need for more focused content in specific areas. Salm Ward et al. [2] evaluated a crib distribution program paired with safe sleep education, showing that providing practical tools like cribs, along with education, significantly improved adherence to safe sleep practices. A mixed methods study by Hubel et al. [34] investigating the promotion of infant safe sleep and breastfeeding at the community level revealed gaps in both promotion efforts and outcomes. The study analyzed state-level data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) and found that disparities in infant safe sleep practices and breastfeeding rates persist, particularly among non-Hispanic Black and American Indian/Alaskan Native populations. The qualitative component highlighted the importance of conversational approaches in promoting safe sleep and breastfeeding, with community collaboration identified as a key factor in addressing organizational capacity limitations. The study concluded that tailored program offerings and enhanced community collaboration could help reduce disparities in infant health outcomes, particularly in underserved populations. These findings underscore the potential of community-level interventions to improve both safe sleep and breastfeeding practices, though more efforts are needed to overcome barriers to access and uptake.

A quasi-experimental study [35] evaluated the effects of a structured sleep education program on mothers’ knowledge and attitudes toward infant sleep. The study included 208 mothers with infants aged 5–12 months from all Jordanian governorates. The intervention group showed a significant improvement in mothers’ sleep knowledge over time (p < 0.001), particularly regarding the benefits of establishing bedtime routines. However, there was no significant improvement in mothers’ attitudes toward infant sleep (p = 0.011), suggesting that while knowledge can be increased through education, changing attitudes may require a longer intervention period.

3.4. Maternal/Parental Satisfaction Outcomes

The study by Leichman et al. [21] on the Customized Sleep Profile (CSP) intervention assessed parental satisfaction with the mHealth behavioral sleep intervention delivered via a smartphone application. Caregivers reported high levels of satisfaction with the personalized recommendations and psychoeducation provided by the CSP. Specifically, 52.4% of caregivers of infants identified as problem sleepers perceived improvements in their infant’s sleep post-intervention, which contributed to the high satisfaction levels. The convenience of the app, coupled with the relevance of the tailored advice, was highlighted as a key factor in the positive feedback. Parents also appreciated the noticeable improvements in their infants’ sleep patterns, including fewer night wakings and longer sleep stretches. This, in turn, led to reduced parental stress and an overall enhancement of family well-being.

Personalized and culturally relevant approaches were particularly well-received by participants. Salm Ward et al. [33], in their evaluation of the “My Baby’s Sleep” (MBS) intervention, found that African American families from under-resourced neighborhoods expressed high levels of satisfaction with the program. The personalized nature of the intervention, along with its cultural relevance, addressed specific family needs and practices, fostering a sense of support and engagement. The structured sessions, educational materials, and guidance from supportive coaches were consistently praised, contributing to both high retention rates and a positive reception of the program.

Prenatal and postnatal guidance also played a significant role in increasing maternal confidence and satisfaction. Sweeney et al. [31] tested a behavioral–educational sleep intervention delivered to first-time mothers, and participants reported high satisfaction with both the prenatal guidance and the postnatal follow-up support. Mothers in the sleep intervention group (SIG) experienced an increase in nocturnal sleep duration and improved perceptions of their own sleep quality, which helped to reduce stress and boost confidence in managing both maternal and infant sleep. The participants found the educational content highly valuable, and their overall positive experiences contributed to higher satisfaction in their parenting roles [31].

3.5. Impact on Infant and Parental Well-Being

Educational interventions aimed at promoting safe sleep practices have demonstrated positive impacts on both infant and parental well-being. Improved sleep patterns in infants contribute to better health outcomes, while parents benefit from increased confidence in sleep management, reduced stress, and improved mental health.

Paul et al. [27] investigated the Responsive Parenting (RP) intervention, which included a sleep component aimed at obesity prevention. Infants in the RP group exhibited longer sleep durations, more consistent bedtime routines, and a greater ability to self-soothe compared to the control group. These improved sleep patterns were associated with broader developmental benefits, such as enhanced cognitive, psychomotor, and socioemotional development. Moreover, better sleep supported infants’ emotional regulation and behavioral management while also improving parental mental health, thereby fostering a healthier developmental environment. This intervention likely contributed to better overall health and developmental outcomes. Similarly, Santos et al. [29] found that behavioral sleep hygiene counseling significantly increased infants’ average nighttime sleep duration and had positive effects on their linear growth and neurocognitive development. This highlights the broader developmental benefits of improving infant sleep hygiene through educational interventions.

Sweeney et al. [31] emphasized the dual benefit of educational interventions for both mothers and infants. Their study demonstrated that a behavioral–educational sleep intervention significantly increased nocturnal sleep duration for mothers, enhanced their perceptions of sleep quality, and boosted their confidence in managing infant sleep. This underlines the importance of addressing parental well-being in interventions, as improved parental mental health can positively influence infant care.

Rouzafzoon et al. [28] assessed the effectiveness of a preventive behavioral sleep intervention (BSI) on infant sleep patterns and maternal health. The intervention significantly improved infant sleep patterns, including longer nighttime sleep periods and earlier bedtimes. Additionally, maternal sleep quality improved, and depression levels decreased, indicating a comprehensive benefit to both infant and family well-being. Maternal sleep quality was assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and depression levels were measured using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), providing validated insights into the positive effects of the intervention on family health. In contrast, Santos et al. [30] evaluated a sleep intervention in Pelotas, Brazil, and found no statistically significant differences in nighttime sleep duration between the intervention and control groups at any age. This suggests that while some educational interventions succeed in improving sleep patterns, others may not effectively increase sleep duration, particularly in certain populations or contexts.

4. Discussion

This systematic review examined the effectiveness of domiciliary educational programs aimed at enhancing safe sleep practices among caregivers responsible for infants between birth and 12 months of age. Our findings highlight the positive impact of these interventions, which include hospital-based programs, home visits, and digital tools, in improving parental knowledge, adherence to safe sleep guidelines, and overall satisfaction. These strategies have been shown to reduce unsafe sleep behaviors and enhance infant health outcomes. However, our review underscores the need for future research to address the variability in intervention methods, cultural contexts, and geographic focus while also advocating for standardized outcome measures and long-term studies to fully assess the sustained impact of these interventions.

In contrast, Shiells et al. [5], in their systematic review, focus on high-risk populations, particularly families in deprived neighborhoods, whose infants face a greater risk of sudden unexpected death in infancy (SUDI). Their analysis utilizes the COM-B model and the Theoretical Domains Framework to explore the behavioral change components of safer sleep interventions. While similar to our review in terms of advocating for educational interventions, Shiells et al. [5] emphasize that traditional safer sleep messaging may not be as effective for high-risk groups. Instead, they advocate for interventions that go beyond knowledge dissemination and focus on modifying parental capability, opportunity, and especially motivation—the latter being crucial in driving safer sleep practices in vulnerable populations. Their findings suggest that practitioners need to tailor their approaches to these high-risk groups by incorporating practical demonstrations and peer support and addressing parents’ goals and emotional factors, which are often barriers to adopting safer sleep behaviors.

Our review contributes to the literature by providing a comprehensive evaluation of educational strategies in the broader population, while Shiells et al. [5] fill a critical gap by analyzing behavior change techniques in the context of SUDI and high-risk infants. The emphasis by Shiells et al. on addressing the motivational and environmental factors that influence behavior offers a more targeted approach for populations where traditional methods may fall short. Together, these reviews complement one another by providing a well-rounded understanding of how safer sleep interventions can be optimized, both for general populations and for those at heightened risk of infant mortality.

Of interest, a recently published systematic review protocol aims to evaluate the effectiveness of preventive parental education provided from pregnancy to 1 month postpartum on infant sleep, postpartum parental sleep, and parental depression [6]. Given that untreated infant sleep problems can persist into childhood and are associated with developmental issues, this review will consider experimental and quasi-experimental studies focusing on interventions that promote healthy sleep habits, such as self-soothing and independent sleeping techniques, starting during pregnancy. The review aims to assess outcomes related to infant sleep patterns, the number of parental awakenings, nocturnal sleep time, and parental depression. It also aims to compare these outcomes to standard care or alternative interventions and use meta-analysis where possible. The findings are expected to inform future recommendations for improving both infant and parental health by targeting sleep-related problems early in the perinatal period [6].

Our review reveals a consistent pattern across studies: educational interventions play a pivotal role in substantially improving parental compliance with safe sleep protocols. For example, hospital-based interventions, such as the comprehensive sleep safety programs described by Goodstein et al. and McDonald et al., provided foundational education that improved parental knowledge at the point of discharge and maintained adherence over time [1,23]. These findings underscore the value of intensive early education delivered before families transition to home care. Goodstein et al. found that 99.8% of parents were aware of the supine sleep position as the safest practice at discharge, with an 84.9% adherence rate at four months follow-up [1]. This high retention rate highlights the importance of structured and early intervention.

Several studies show that continuous or follow-up education is crucial for maintaining adherence to safe sleep guidelines. Mathews et al. emphasized the long-term benefits of ongoing education, noting a significant reduction in the use of soft bedding in infant sleep environments over time [14]. Similarly, Brashears et al. demonstrated that incorporating follow-up calls and personalized sleep education during well-child visits led to a substantial reduction in unsafe sleep practices, reinforcing the need for continuous reinforcement of safe sleep practices throughout infancy [15].

Mobile health (mHealth) interventions have emerged as effective tools for reinforcing safe sleep practices, especially in combination with other methods. Moon et al. evaluated a mobile health intervention that provided daily educational messages and videos to mothers over a 60-day period, leading to significant improvements in adherence to safe sleep practices, such as supine sleeping and room-sharing without bed-sharing [24]. Notably, combining mHealth with in-person nursing support resulted in better adherence compared to either intervention alone, suggesting that digital tools can effectively complement traditional education.

The cultural context in which these interventions are implemented plays a pivotal role in their effectiveness. Studies like those by Salm Ward et al. demonstrate that tailored educational interventions, which account for cultural practices and specific family dynamics, can enhance parental adherence to safe sleep practices in underserved communities [32]. Addressing specific cultural practices and socioeconomic factors allows for more practical and sustainable changes in behavior, particularly in high-risk populations.

The delivery method of educational interventions also influences their effectiveness. Hospital-based programs tend to provide a structured and standardized approach, as seen in Goodstein et al., but may lack the personalized follow-up found in home-based interventions [1]. Home visiting programs, as discussed by Santos et al., offer a tailored approach that accounts for individual family needs and cultural factors but may require more resources and logistical support to implement [29]. Digital interventions, as explored by Moon et al., provide scalable solutions that are accessible to a broader audience, although they may lack the personal touch and immediate feedback provided by in-person education [24].

Despite the effectiveness of these interventions, variability remains in terms of outcomes, particularly regarding the long-term sustainability of behavior change. Studies like those by Paul et al. and Santos et al. highlight the need for standardized outcome measures and extended follow-up periods to fully assess the long-term impact of educational strategies on infant sleep patterns [27,29]. Moreover, the variability in intervention delivery, as well as differences in cultural and geographic contexts, suggests that future research should focus on tailoring interventions to specific populations and settings.

The implementation of safe sleep practices for infants is influenced by a combination of caregiver knowledge, cultural factors, and the quality of information provided by healthcare professionals. Despite high levels of parental education, only a few caregivers receive safe sleep education from healthcare providers. This highlights the critical need for comprehensive and effective educational programs by healthcare providers to ensure caregivers are well-informed about safe sleep practices. Cultural practices, parental fatigue, and convenience also influence adherence, suggesting that interventions need to be culturally sensitive and address practical challenges [36].

In addition to caregiver education and healthcare-provider communication, socioeconomic and demographic factors also significantly impact the implementation of safe sleep practices. Lower socioeconomic status, lack of access to healthcare resources, and lower educational attainment among caregivers have been associated with decreased adherence to safe sleep recommendations. Additionally, racial and ethnic disparities play a role, with minority groups often facing barriers such as language differences and mistrust of healthcare systems [37].

Several barriers hinder the consistent implementation of safe sleep practices, including gaps in healthcare providers’ knowledge and communication. Angal et al. noted that although 98% of physicians in South Dakota understood the importance of discussing SIDS with parents, many did not provide comprehensive advice covering all aspects of safe sleep. Factors such as years since training significantly influenced whether providers shared detailed information on safe sleep, with those more recently trained being more likely to do so [38]. Similarly, Cole emphasized that inconsistent advice from healthcare professionals leads to confusion among caregivers, reducing adherence to safe sleep practices [39]. In another study by Dorjulus et al., barriers such as language differences, cultural beliefs, and socioeconomic factors were identified as significant obstacles to the dissemination of safe sleep information [40].

Educational interventions aimed at promoting safe sleep practices for infants have shown varying degrees of effectiveness. One successful strategy includes direct education of healthcare professionals, which subsequently influences their interactions with caregivers. For example, Moon et al. emphasized the importance of educating healthcare providers about safe sleep guidelines and addressing misconceptions that could hinder adherence [41]. This education allows providers to model safe sleep practices consistently and provide accurate information to parents. It has been shown that healthcare providers who receive comprehensive training on safe sleep guidelines are more likely to counsel parents effectively and demonstrate these practices in clinical settings, thereby improving overall adherence to safe sleep recommendations [41].

Moreover, incorporating culturally sensitive approaches and addressing specific barriers faced by different communities are essential for the success of these interventions. Naugler et al. [42] pointed out that interventions tailored to address cultural beliefs and practices surrounding infant sleep can enhance the effectiveness of educational programs. For example, community workshops and targeted messaging that respect and integrate cultural values have been shown to improve the acceptance and implementation of safe sleep practices. This approach ensures that the educational content is relevant and relatable to diverse caregiver populations, thereby increasing the likelihood of behavior change and adherence to recommended practices [42].

While this systematic review offers valuable insights into safe infant sleep practices and effective interventions, several limitations must be noted. The heterogeneity of studies, varying in population, intervention type, and outcome measures, complicates direct comparisons and generalizations. Publication bias, favoring studies with positive findings, may skew effectiveness assessments. The limited geographic scope, with a concentration in the United States and Australia, reduces the generalizability to diverse cultural and socioeconomic contexts. Short-term follow-up data restrict understanding of long-term behavioral changes, necessitating longitudinal studies. Variability in the implementation of intervention and reliance on self-reported data introduce potential biases and inconsistencies. The lack of standardized outcome measures complicates data synthesis, while small sample sizes in some studies limit statistical power and increase the risk of type II errors. Addressing these limitations in future research is essential for developing more effective, universally applicable interventions to promote safe infant sleep and reduce sleep-related infant deaths.

Future public health initiatives should enhance educational campaigns with clear, consistent messaging and culturally tailored interventions involving family members to improve adherence to safe sleep practices. Integrating user-friendly digital tools like mHealth and EHR portals is essential for broadening the reach and efficacy of educational efforts and providing personalized feedback and reminders. Special attention must be given to high-risk groups, such as young, less educated, and minority mothers, through targeted support programs like My Baby’s Sleep (MBS). Continuous professional training for healthcare providers is necessary to bridge gaps in knowledge and practice regarding safe sleep guidelines. Future research should investigate the long-term effects of these interventions on infant health, using longitudinal studies to assess behavioral sustainability. Finally, community involvement, including collaboration with local leaders and networks, is critical for effectively disseminating safe sleep messages and ensuring culturally relevant interventions.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review highlights home-based educational interventions’ significant impact on improving infant sleep care. These interventions effectively enhance parental knowledge and adherence to safe sleep practices, contributing to better infant health outcomes and higher parental satisfaction. The findings underscore the need for multifaceted and culturally tailored educational strategies to address the unique needs of diverse families. Future research should focus on addressing current limitations, such as study heterogeneity and short-term follow-up, to develop more effective, universally applicable interventions that promote safe infant sleep and reduce sleep-related infant mortality.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/children11111337/s1, Supplementary File S2: Search Strategy; Supplementary File S3: Quality Assessment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. and A.S.; methodology, A.S.; software, M.A.; validation, D.M., M.D., V.V. and A.S.; formal analysis, M.A. and D.M.; investigation, M.A.; resources, A.S.; data curation, M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A. and A.S.; writing—review and editing, M.A., D.M. and A.S.; supervision, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the articles.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work, the AI tool Chat GPT was used to improve the readability and language of the manuscript, and subsequently, the authors revised and edited the content produced by the AI tool as necessary, taking full responsibility for the ultimate content of the present manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Goodstein, M.H.; Bell, T.; Krugman, S.D. Improving Infant Sleep Safety through a Comprehensive Hospital-Based Program. Clin. Pediatr. 2015, 54, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salm Ward, T.C.; McClellan, M.M.; Miller, T.J.; Brown, S. Evaluation of a Crib Distribution and Safe Sleep Educational Program to Reduce Risk of Sleep-Related Infant Death. J. Community Health 2018, 43, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiffler, D.; Matemachani, S.M.; Crane, L. Supporting African American Mothers during Nurse Home Visits in Adopting Safe Sleep Practices. Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2020, 45, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, R.G.; Rajabali, F.; Aragon, M.; Colbourne, M.; Brant, R. Education about crying in normal infants is associated with a reduction in pediatric emergency room visits for crying complaints. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2015, 36, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiells, K.; Cann, H.; Pease, A.; McGovern, R.; Woodman, J.; Barrett, S.; Barlow, J. A Behaviour Change Analysis of Safer Sleep Interventions for Infants at Risk of Sudden and Unexpected Death. Child Abuse Rev. 2024, 33, e2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaka, E.; Ooshige, N.; Ueki, S.; Morokuma, S. Effectiveness of Preventive Parental Education Delivered from Pregnancy to 1 Month Postpartum for Improving Infant Sleep and Parental Sleep and Depression: A Systematic Review Protocol. JBI Evid. Synth. 2024, 22, 1355–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Systematic Review Service–Tools & Resource. Available online: https://www.nihlibrary.nih.gov/services/systematic-review-service/tools-resources (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analyses. Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 21 April 2024).

- Downes, M.J.; Brennan, M.L.; Williams, H.C.; Dean, R.S. Development of a Critical Appraisal Tool to Assess the Quality of Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrinc, G.; Davies, L.; Goodman, D.; Batalden, P.; Davidoff, F.; Stevens, D. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised Publication Guidelines from a Detailed Consensus Process. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2015, 46, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Non-Randomised Studies of Interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health Research. Definitions of Feasibility vs. Pilot Studies. Available online: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/guidance-on-applying-for-feasibility-studies/20474 (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Mathews, A.; Joyner, B.L.; Oden, R.P.; He, J.; McCarter, R., Jr.; Moon, R.Y. Messaging Affects the Behavior of African American Parents with Regards to Soft Bedding in the Infant Sleep Environment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Pediatr. 2016, 175, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brashears, K.A.; Erdlitz, K. Screening and Support for Infant Safe Sleep: A Quality Improvement Project. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2020, 34, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canty, E.A.; Fogel, B.N.; Batra, E.K.; Schaefer, E.W.; Beiler, J.S.; Paul, I.M. Improving Infant Sleep Safety via Electronic Health Record Communication: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 468, Erratum in BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlin, R.F.; Abrams, A.; Mathews, A.; Joyner, B.L.; Oden, R.; McCarter, R.; Moon, R.Y. The Impact of Health Messages on Maternal Decisions About Infant Sleep Position: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Community Health 2018, 43, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, D.A.; Barsman, S.G.; Forsythe, P.; Damato, E.G. Caring about Preemies’ Safe Sleep (CaPSS): An Educational Program to Improve Adherence to Safe Sleep Recommendations by Mothers of Preterm Infants. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2018, 32, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, W.A.; Hutton, E.; Brant, R.F.; Collet, J.P.; Gregg, K.; Saunders, R.; Ipsiroglu, O.; Gafni, A.; Triolet, K.; Tse, L.; et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of an Intervention for Infants’ Behavioral Sleep Problems. BMC Pediatr. 2015, 15, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichman, E.S.; Gould, R.A.; Williamson, A.A.; Walters, R.M.; Mindell, J.A. Effectiveness of an mHealth Intervention for Infant Sleep Disturbances. Behav. Ther. 2020, 51, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.M.A.; Oliveira, J.R.A.; Salgado, C.C.G.; Marques, B.L.S.; Oliveira, L.C.F.; Oliveira, G.R.; Rodrigues, T.S.; Ferreira, R.T. Sleep Habits in Infants: The Role of Maternal Education. Sleep Med. 2018, 52, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, E.M.; Davani, A.; Price, A.; Mahoney, P.; Shields, W.; Musci, R.J.; Solomon, B.S.; Stuart, E.A.; Gielen, A.C. Health Education Intervention Promoting Infant Safe Sleep in Paediatric Primary Care: Randomised Controlled Trial. Inj. Prev. 2019, 25, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, R.Y.; Hauck, F.R.; Colson, E.R.; Kellams, A.L.; Geller, N.L.; Heeren, T.; Kerr, S.M.; Drake, E.E.; Tanabe, K.; McClain, M.; et al. The Effect of Nursing Quality Improvement and Mobile Health Interventions on Infant Sleep Practices: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017, 318, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, R.Y.; Corwin, M.J.; Kerr, S.; Heeren, T.; Colson, E.; Kellams, A.; Geller, N.L.; Drake, E.; Tanabe, K.; Hauck, F.R. Mediators of Improved Adherence to Infant Safe Sleep Using a Mobile Health Intervention. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20182799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabaweesi, R.; Whiteside-Mansell, L.; Mullins, S.H.; Rettiganti, M.R.; Aitken, M.E. Field Assessment of a Safe Sleep Instrument Using Smartphone Technology. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2019, 4, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, I.M.; Savage, J.S.; Anzman-Frasca, S.; Marini, M.E.; Mindell, J.A.; Birch, L.L. INSIGHT Responsive Parenting Intervention and Infant Sleep. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20160762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouzafzoon, M.; Farnam, F.; Khakbazan, Z. The Effects of Infant Behavioural Sleep Interventions on Maternal Sleep and Mood, and Infant Sleep: A Randomised Controlled Trial. J. Sleep Res. 2021, 30, e13344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, I.S.; Bassani, D.G.; Matijasevich, A.; Halal, C.S.; Del-Ponte, B.; da Cruz, S.H.; Anselmi, L.; Albernaz, E.; Fernandes, M.; Tovo-Rodrigues, L.; et al. Infant Sleep Hygiene Counseling (Sleep Trial): Protocol of a Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, I.S.; Del-Ponte, B.; Tovo-Rodrigues, L.; Halal, C.S.; Matijasevich, A.; Cruz, S.; Anselmi, L.; Silveira, M.F.; Hallal, P.R.C.; Bassani, D.G. Effect of Parental Counseling on Infants’ Healthy Sleep Habits in Brazil: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1918062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, B.M.; Signal, T.L.; Babbage, D.R. Effect of a Behavioral-Educational Sleep Intervention for First-Time Mothers and Their Infants: Pilot of a Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2020, 16, 1265–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, J.L.; Tussing-Humphreys, L.M.; Goodman, M.H.; Landry, A.S. Infant Activity and Sleep Behaviors in a Maternal and Infant Home Visiting Project among Rural, Southern, African American Women. Matern. Health Neonatol. Perinatol. 2018, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salm Ward, T.C.; McPherson, J.; Kogan, S.M. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Tailored Infant Safe Sleep Coaching Intervention for African American Families. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhammad, S.; Bani Younis, A.; Ahmed, A.H. Impact of a Structured Sleep Education Program on Mothers’ Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Infant Sleeping. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, R.; Menon, M.; Russell, R.B.; Smith, S.; Scott, S.; Berns, S.D. Community infant safe sleep and breastfeeding promotion and population level-outcomes: A mixed methods study. In Midwifery; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmadi, T.S.; Sobaihi, M.; Banjari, M.A.; Bakheet, K.M.A.; Modan Alghamdi, S.A.; Alharbi, A.S. Are Safe Sleep Practice Recommendations for Infants Being Applied Among Caregivers? Cureus 2020, 12, e12133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.S.; Corwin, M.J. Safe Infant Sleep Practices: Parental Engagement, Education, and Behavior Change. Pediatr. Ann. 2017, 46, e291–e296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angal, J.; Gogoi, M.; Zenel, J.; Elliott, A.J. Physicians Knowledge and Practice of Safe Sleep Recommendations for Infants in South Dakota. S. D. Med. 2019, 72, 349–353. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, R.; Young, J.; Kearney, L.; Thompson, J.M.D. Infant Care Practices, Caregiver Awareness of Safe Sleep Advice and Barriers to Implementation: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorjulus, B.; Prieto, C.; Elger, R.S.; Oredein, I.; Chandran, V.; Yusuf, B.; Wilson, R.; Thomas, N.; Marshall, J. An Evaluation of Factors Associated with Safe Infant Sleep Practices among Perinatal Home Visiting Participants in Florida, United States. J. Child Health Care 2023, 27, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, R.Y.; Hauck, F.R.; Colson, E.R. Safe Infant Sleep Interventions: What is the Evidence for Successful Behavior Change? Curr. Pediatr. Rev. 2016, 12, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naugler, M.R.; DiCarlo, K. Barriers to and Interventions that Increase Nurses’ and Parents’ Compliance with Safe Sleep Recommendations for Preterm Infants. Nurs. Women’s Health 2018, 22, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).