Abstract

Introduction: In Jordan, mental health morbidity among children and adolescents is on the rise. Several studies in Jordan have assessed mental health issues and their associated factors among adolescents; however, there remains a lack of a collation of data regarding such issues. Objectives: To review the prevalence rates of mental health problems among children and adolescents in Jordan to understand the evidence base concerning psychiatric morbidity. Methods: The PubMed database, Cochrane Library, Virtual Health Library (VHL) Lilac, and APA PsycArticles were searched for literature published between January 2010 and May 2023. Studies were included if they were conducted on children and adolescents (≤19 years), were observational studies that reported prevalence data regarding psychosocial problems, and were studies conducted in Jordan. Results: The search yielded 211 records, of which 33 studies were assessed for eligibility and 28 met the inclusion criteria. The sample age ranged from 6–19 years. The prevalence rates ranged from 7.1% to 73.8% for depression, 16.3% to 46.8% for anxiety, 13.0–40.6% for ADHD, 11.7–55.2% for overall emotional and behavioral difficulties, 16.2–65.1% for PTSD, and 12–40.4% for eating disorders. Conclusions: The findings highlight the magnitude of mental health problems among children and adolescents and the heterogeneity of the results. Further studies are needed to investigate the prevalence of eating disorders among refugees, as well as sleeping disorders and substance use disorders among all adolescents.

1. Introduction

Worldwide, the prevalence of mental health problems among adolescents aged 10–19 is high and continues to increase, with a recent review reporting an increase in the age-standardized rate of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for mental disorders in children and adolescents from 803.8 per 100,000 to 833.2 per 100,000 from 1990 to 2019 [1]. In 2019, it was estimated that one in seven adolescents experienced a mental health disorder, with anxiety and depressive disorders accounting for 40% of mental disorders, followed by conduct disorders (20.1%) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (19.5%) [2]. Globally, the burden of depressive disorders is high among adolescents aged 10–24 [3]. The recent COVID-19 pandemic has further negatively impacted the emotional well-being of adolescents due to its inherent characteristics, such as prolonged school closure, strict social isolation from peers, teachers, extended family, and community networks, and the pandemic itself [4].

In Jordan, mental health morbidity among children and adolescents is on the rise, especially among refugee children. Jordan hosts the second-highest share of refugees per capita in the world, where 48% of refugees are children (UNICEF, 2019) [5]. Refugees are vulnerable to mental health disorders since they are subjected to numerous risks and stressful events. Adolescents, making up 21% of the total Jordanian population, are vulnerable to discrimination, stigma, social exclusion, educational difficulties, risk-taking behaviors, physical ill-health, and human rights violations, which in turn worsens their mental well-being [6].

Many studies [7,8,9,10] in Jordan have assessed mental health issues and their associated factors among adolescents; however, there remains a lack of a collation of data regarding such issues. Therefore, this study aimed to review the prevalence rates of mental health and psychosocial problems among adolescents in Jordan to better understand the evidence base concerning adolescent psychiatric morbidity. The main research question was “What is the available evidence regarding the prevalence of mental health issues among children and adolescents in Jordan?” The objectives are to identify the prevalence and type of morbidity, as well as the associated factors, identify research priorities and gaps, and the problems in primary research that should be rectified in future studies. A scoping review was chosen for this study because this type of review explores the breadth or extent of the literature, maps and summarizes the evidence, and informs future research [11]. Unlike systematic reviews, scoping reviews are not meant to inform practice or policy; instead, they are used to inform future research [11].

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search

A preliminary search was conducted using the PubMed database to familiarize ourselves with the literature, refine the aims of the research, and identify relevant keywords and medical subject headings (MeSH terms). The identified keywords were used during the main search (Box 1). The PubMed database, Cochrane Library, and Virtual Health Library (VHL) Lilac were searched on 19 May 2023 for literature published between January 2010 and 2023. In addition, APA PsycAricles was searched for relevant literature. This time period (2010–2023) was chosen since several traumatic events took place in Jordan. For example, in 2011, Syrian refugees chose asylum in Jordan due to the civil war that broke out in March 2011, in addition to the COVID-19 pandemic that started in 2019. The search was not limited by the type of publication or language used. The results were imported into Rayyan where screening of the results was initiated. The Rayyan tool is a web and mobile application to facilitate the screening of articles for scoping reviews [12]. The retained articles were hand searched for relevant literature. The PRISMA-ScR guidelines were followed when preparing the articles.

Box 1. Search terms used to search the PubMed database from 2010 to May 2023.

- 1.

- “Mental Health” [Mesh] or “Mental illness” [tw] or “Mental Disorders” [Mesh] or anxiety[tw] or “Depression” [Mesh] or “Depressive Disorder” [Mesh] or “Psychosocial problems” [tw] or “psychiatric disorders” [tw] or "Problem Behavior” [Mesh] or “behavioral problem” [tw] or “Conduct Disorder” [Mesh] or “emotional problems” [tw] or “Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity” [Mesh] or “Adverse Childhood Experiences” [Mesh] or “Adverse childhood experiences” [tw] or fear [tw] or attention-deficit [tw] or “attention deficit” [tw] or “Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder” [Mesh] or “Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic” [Mesh] or “Intellectual Disability” [Mesh] or “Autistic Disorder” [Mesh] or “Autism Spectrum Disorder” [Mesh]

AND

- 2.

- “Adolescent” [Mesh] or “Child” [Mesh] or child [tw]

AND

- 3.

- “Jordan” [Mesh]

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

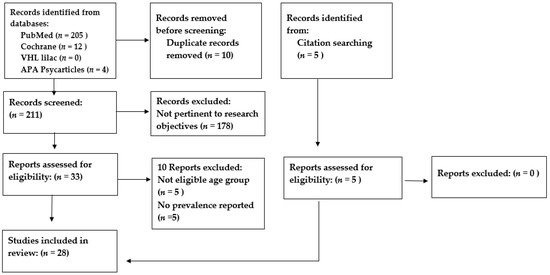

Only studies that met the eligibility criteria were included in this review: (1) studies conducted among children and/or adolescents aged ≤19 years in the host and/or the refugee populations, (2) observational studies that reported prevalence data regarding mental health or psychosocial problems, and (3) studies conducted in Jordan. We excluded studies that were qualitative in design. Two authors independently screened the retrieved 211 titles and abstracts according to a pre-specified inclusion criterion. When the title or abstract did not clearly indicate whether an article should be included or excluded, the full article was read to determine if it met the inclusion criteria. Disagreement between the authors was solved by consensus, and the reasons for exclusion were recorded. A flow chart detailing the number of studies included and excluded at each stage is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A flow chart detailing the number of studies included and excluded from the review.

2.3. Data Extraction

Extraction was based on predefined data fields that included author and publication year, study design, study population, sample size, prevalence rate and associated factors, instrument(s) used, and main outcomes studied. One author extracted the data from the studies, and a second author checked the extracted data. Disagreement was resolved by a discussion between the two authors. When no agreement was reached, a third author was called upon to decide [13].

3. Results

3.1. Studies’ Characteristics

A total of 28 studies [7,8,9,10,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37] were included in this review. Of those, 15 studies [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,25,29,33,35,36,37] examined mental health problems among Jordanian adolescents only, 3 studies were conducted among Syrian refugees [7,9,26], 3 studies included both Jordanian and Syrian adolescents [8,10,27], 2 studies were conducted among adolescents who resided in refugee camps [24,28], and 5 studies did not specify ethnicity [23,30,31,32,34]. The sample age ranged from 6–19 years. A total of 19 studies included data from schoolchildren [7,8,10,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,25,26,29,32,33,37], 2 studies included data from adolescents residing in refugee camps [24,28], 1 study included data from Syrian refugees living within the Jordanian community [9], 1 study included data from adolescents attending health clinics [34], 2 studies [35,36] included data from adolescents residing in institutional care centers, and 1 study included data from participants enrolled in a Mercy Corp registry [27]. Four studies examined female-only samples [15,18,20,24]. In total, 20 screening tools were used to assess mental health disorders and psychosocial problems (Table 1). Table 2 presents the summary of the studies’ findings.

Table 1.

Mental health screening tools used in the retained studies.

Table 2.

Summary of the results.

3.2. Depression

A cross-sectional study of 1103 (605 females and 498 males) Jordanian adolescents aged 13–18 years attending public schools in Irbid reported that the prevalence of any mental disorder (mood disorders and anxiety disorders) was 28.6%, and the prevalence of mood disorders was reported to be 22.4% according to PHQ-A. Mood disorders included major depressive disorder (7.1%), dysthymic disorder (9.8%), and minor depressive disorder (11.2%) [17].

The prevalence of depressive symptoms was reported in 12 studies [9,10,16,17,19,21,23,24,31,34,36,37]. These studies used different tools to assess depression: the CES-C questionnaire [36], the CES-DC questionnaire [10,16], a modified version of the CES-C questionnaire used for children and adolescents, the CDI-2 questionnaire [9], the BDI-II [19], the PHQ-A [17], and a modified version of the PHQ-A, known as PHQ-9 [10]. The overall prevalence of depressive symptoms ranged from 7.1% to 73.8% [9,10,16,17,19,36] among adolescents. The prevalence ranged from 28.3% to 51.8% [9,10] among Syrian refugee adolescents and from 27.2% to 73.8% [10,16,17,19,36] among Jordanian adolescents. One study measured the prevalence of depressive symptoms among youths aged 7 to 18 years who reside in institutional care centers, which reported a rate of 45%. Five studies reported the severity of depression [19,21,23,24,31] using the BDI-II questionnaire [19,21,23,31] and the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS) [24]. The prevalence of moderate depression ranged from 16.9%-19% [19,23,31], whereas severe depression ranged from 14.6–24% [19,23,31] and girls reported higher rates than boys [21]. The prevalence of moderate to extremely severe depressive symptoms was reported at 39.6% among married Palestinian girls aged 14–18 years who resided in refugee camps [24].

The CES-D and the CES-DC are both self-report depression questionnaires with 20 questions to rate depressive symptoms over the previous week. Each question had a score from 0 to 3 and the total score ranges from 0–60. Weissman et al. (1980) [38] the developers of the CES-DC, used a cut-off point of 15 as being suggestive of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. Hence, scores over 15 suggest significant levels of depressive symptoms. Khader Y et al. [7] assessed the prevalence of depressive symptoms among Jordanian and Syrian adolescents using two screening tools: CES-DC and PHQ-9. According to both screening tools, Syrians reported higher rates of depressive symptoms compared to Jordanian adolescents, where findings from the CES-DC questionnaire showed a prevalence rate of 27.2% among Jordanians and 28.3% among Syrian refugees, and the findings from the PHQ-9 questionnaire revealed prevalence rates of 35.2% and 37.1% among Jordanians and Syrians, respectively. Malakeh M et al. [16] assessed the prevalence of depressive symptoms among Jordanian adolescents using the CES-DC questionnaire, which revealed a staggering prevalence of 73.8%. However, the cut-off point used by Malak was much lower compared to the cut-off point used by Khader Y et al. [10] (≥15 vs. >30). Alassaf A et al. [34] also leveraged the CES-DC questionnaire to assess the prevalence of depressive symptoms among adolescents aged 10–17 years, with type 1 diabetes (T1D). Adolescents who attended the Pediatric endocrine clinic at Jordan University Hospital from February 2019 and February 2020 were asked to fill out the self-reported questionnaire. Out of the 108 children enrolled, 50 children (46.3%) had a depression score of 15 or more.

The different studies assessed the factors associated with depression. Among Jordanian and Syrian refugee adolescents, female gender [10,16,17,19,23,31,34,37], older age [19,23,37], residing in families with a monthly income of less than JD 300 and a residing in families with low monthly incomes, reporting a chronic health problem, a mental health problem, a learning difficulty, or a psychiatric diagnosis [19,37], not having resilient traits [9,10], and having high emotional and peer relation problems were associated with a higher risk of developing depressive symptoms [10]. Among the Jordanian adolescents, older students [21], those with a parental history of mental health disorders [17], poor or medium academic achievement (<70%) [16], a family income of less than JD 300 (USD 423), reporting a chronic health problem [19], a mental health problem [19], a learning difficulty [19,21], a psychiatric diagnosis, and seeking psychological help in the past were at a higher risk of developing depressive symptoms [19]. Among the Syrian refugee adolescents experiencing more traumatic life events was associated with higher depression scores [9]. Internet addiction [16], previous trauma, and father’s educational level [24] were predictors of depression [16] and experiencing difficulties with online education during COVID-19 were reported as predictors of both depression and anxiety [23].

3.3. Anxiety

Four studies [10,16,17,24] reported the prevalence rates of anxiety among adolescents. One study reported a prevalence of 41.5% and 46.8% among Jordanian and Syrian adolescents, respectively, using the GAD-7 screening tool [10]. The second study reported a prevalence of 16.3% among Jordanian adolescents using the PHQ-A screening tool, and the third reported a prevalence of 42.1% among Jordanian adolescents using the CES-DC tool. The PHQ-A questionnaire, which was used by Alslman E et al. [17], was not based on total scores, but instead on specific conditions or responses which should be met to provide a provisional diagnosis. According to Khader Y et al.’s study, Syrian refugee adolescents compared to Jordanian adolescents suffered from higher prevalence rates of anxiety (41.5% vs. 46.8%). The fourth study assessed the severity of anxiety and stress symptoms among Palestinian married girls who resided in refugee camps. Using the DASS tool, it was noted that 35.6% and 9.8% suffered from moderate to extremely severe anxiety and stress symptoms, respectively [24].

Jordanian and Syrian refugee adolescents who reported high emotional symptoms, high conduct problems, and hyperactivity disorders were more likely to develop anxiety [10]. Factors associated with higher rates of anxiety among Jordanian adolescents included female gender, older students [16,17], having a family income of <JD 250 (USD 352) [16], a parental history of mental disorders [17], medium or poor academic achievement (<70%), and having a severe level of Internet addiction [16]. Female adolescents experienced higher severity levels of anxiety compared to males [21,23]. Feeling safe was reported as a protective factor among Jordanian and Syrian refugee adolescents, and high perceived support among Jordanians was reported as a protective factor [10].

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder was examined in two studies [22,29], and the authors assessed the prevalence of ADHD and its subtypes among Jordanian adolescents aged 6–12 years. The prevalence of ADHD as reported by teachers ranged from 19.2–40.6% [22,29], and 13.0% as reported by parents [29]. Girls and older children experienced lower rates of ADHD and its subtypes. Respectively, the prevalence rate of ADHD subtypes among 6–9-year-old and 10–12-year-old children were 10.8% and 6.3% for inattention, 15.2% and 5.2% for hyperactivity–impulsivity, and 32.4% and 10.7% for the combined subtype [22].

3.4. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Emotional and Behavioral Problems

Four studies reported the prevalence of PTSD among adolescents [7,26,27,36]. One study assessed the prevalence of PTSD among Syrian refugees and Jordanian non-refugee adolescents that were enrolled in a Mercy Corps registry of youth [27]. The study utilized the Child Revised Impact of Events Scale to measure its prevalence and it was reported at 65.1% and 16.2% among Syrian refugees and Jordanian non-refugees, respectively. Two studies assessed the prevalence of PTSD severity among Syrian refugee adolescents [7,26], utilizing the Child Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Scale (CPSS) (cut-off point of ≥21) [7] and the PTSD Checklist—Civilian Version (PCL-C) [26]. Beni Y et al. reported the prevalence rate of moderate to severe symptoms at 31% [7], while Ramadan M et al. reported the prevalence of moderate and severe symptoms at 46.9% and 29.7%, respectively [26]. Across the above-mentioned studies, the prevalence was higher among females and among adolescents of whom at least one of their parents had died. Prevalence did not differ according to total family income, family size [7] or spirituality levels [26]. One study [36] reported a PTSD prevalence rate of 24% among youths aged 7–18 years, who resided in five institutional care centers in Jordan. The study used the University of California, Los Angeles, PTSD Index for DSM-IV (UPID) to report the PTSD prevalence rate. Close peer relationships and reports of abuse were statistically significant predictors of PTSD [36]. Youths who reported abuse were 5.9 times more likely to suffer from PTSD, compared to youths who did not report abuse [36]. Youths who reported having close peer relationships had 93% lower odds of PTSD, compared to youths who did not report having close peer relationships [36].

Three studies assessed the emotional and behavioral problems among adolescents [8,25,35], where two questionnaires were used: the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) [8,25] and the CBCL [35]. In two of the studies where the SDQ was used, a score of 20–40 was indicative of abnormal levels of total difficulties (including emotional, conduct, hyperactivity/inattention, and peer problems as well as prosocial behavior) [8,25], whereas a score of more than 65 on the CBCL questionnaire indicated a borderline clinical cut-off and a score of more than 69 indicated a clinical cut-off [35]. The prevalence of overall total difficulties among Jordanian adolescents ranged significantly from 11.7% to a substantial 52.5% [8,25]. The Syrian adolescents had slightly higher levels of total difficulties compared to the Jordanian adolescents (58.2% vs. 52.5%) [8]. Lower academic achievement was associated with greater emotional and behavioral problems [25] and girls had a higher risk of developing emotional symptoms and hyperactivity/inattention problems than boys had [8,25]. In contrast, the males had higher scores on the peer problems subscale [25]. The Syrian adolescents were more likely to develop overall difficulties and emotional symptoms but had lower rates of peer relationship problems [8]. Prosocial behavior was negatively correlated with emotional symptoms (r = −0.332, p < 0.001), conduct problems (r = −0.415, p < 0.001), and peer relationship problems (r = −0.239, p = 0.001) [8].

3.5. Eating Disorders

A total of four studies [14,15,18,33] assessed the prevalence of eating disorders among Jordanian adolescents. Two studies [15,18] were conducted among females only, and two studies [14,33] involved female and male adolescents. Al kloub I et al. [14], Alfoukha M et al. [18], and Al-Sheyab N et al., [33] utilized the EAT-26 questionnaire (cut-off point ≥ 20) to assess the prevalence of eating disorders and reported a prevalence of 40.4%, 12%, and 23.6% among adolescents, respectively. Mousa Y et al. [15] used the Eating Habits Questionnaire and reported a prevalence of 33.4%. Only one study reported the prevalence of specific types of eating disorders which included bulimia nervosa (0.6%) and binge eating disorders (1.8%), and no anorexic cases were found [15]. Two studies [14,20] assessed the prevalence of body shape dissatisfaction among Jordanian adolescents which utilized the BSQ screening tool. Al Kloub I et al. [14] reported a prevalence of 16.8% among female and male adolescents, and Mousa Y. et al. [20] reported a prevalence at 21.2% among female adolescents.

Female gender [14,33], place of residence (urban more often than rural) [14], excess weight [14,15], distorted perception of weight [14], body shape dissatisfaction [14,15,18], peers’ influence [14,15,18,33], parents’ influence, mass media influence [14,18], increased psychological distress, low self-esteem [18], and high family socio-economic status [14] were associated with the increased prevalence of disordered eating. Body shape dissatisfaction, low self-esteem, negative peer pressure, and being young were significant predictors of the risk of eating disorders [18]. Body shape dissatisfaction was associated with excess weight [14,20], a distorted perception of weight [14], negative eating attitudes, media influence, and peer pressure [20].

4. Discussion

This review highlights the magnitude of mental health disorders and psychosocial problems among children and adolescents living in Jordan. Among the 28 studies included in this review, the prevalence rates among adolescents were 7.1% to 73.8% for depression [9,10,16,17,19,36], 16.3% to 46.8% for anxiety [10,16,17], 13.0–40.6% for ADHD [22,29], 11.7–55.2% for overall emotional and behavioral difficulties [8,25,35], 16.2–65.1% for PTSD [27], and 12–40.4% [14,15,18] for eating disorders. Although there is wide variation among the reported prevalence rates, it is evident that the rates are high. However, the generalizability of the findings is limited because the studies did not include children of all ages and from all regions of the country, as well as the variety of screening tools that were used, in addition to the different study methodologies. Despite a sufficient number of studies published between 2010–May 2023, several publications [7,8,10,15,19,20,21,37] were derived from the same parent study and dataset, hence sharing the same methodology, but reporting different outcomes and/or variables.

Although the prevalence rate of anxiety among Jordanian adolescents was high, Syrian refugee adolescents suffered even higher rates compared to Jordanians. This can be attributable to the numerous traumatic and stressful events that refugees have been subjected to since the Syrian civil war (2011), such as displacement, separation from family, and death of a family member [39,40]. Adolescents’ mental health and psychosocial well-being is also affected by post-conflict conditions in host countries, such as community acceptance, school attendance, family support [41] and differences in cultural, political, and social contexts [42]. Exposure to such harsh conditions increases the likelihood of developing mental health problems [43], which was evident in the high rate of PTSD among the Syrian refugees (65.1%). Alternatively, a lower rate of PTSD (35.1%) was reported among the Syrian adolescents, who were internally displaced in Syria because of the war [44].

It was seen that the prevalence rate of mental health issues among adolescents was higher in cities that were affected by the influx of refugees compared to the capital city, Amman. For example, the prevalence of emotional and behavioral problems among Jordanian adolescents attending schools in cities that are densely populated by refugees was much higher [8] compared to students attending schools in Amman [25] (55.2% vs. 11.7%), in addition to the variation in the prevalence rate of ADHD among students attending schools in Mafraq (40.52%) [22] vs. Amman (19.2%) [29]. However, these findings should be interpreted with caution, due to the different tools used and different sampling techniques. ADHD is one of the most common and well-studied psychiatric disorders in the pediatric population [45]; however, there still remains a limited base of evidence regarding the prevalence rate and its associated factors in Jordan, in addition to the high variability in the prevalence rates that were reported.

The two studies [10,16] that used the CES-DC tool to assess the prevalence rate of depressive symptoms among adolescents, used different cut-off points (≥15 vs. >30). Therefore, the higher prevalence rate of depressive symptoms among Jordanians compared to Syrian refugees is attributable to the difference in the cut-off points used. In addition, the difference in the cut-off points used can explain the wide range of prevalence rates among Jordanians (27.2–73.8%).

Comparisons with other studies in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region should be made with caution since the studies used different screening tools to assess mental health issues or different sampling procedures or investigated different populations. However, a high prevalence of depressive symptoms was reported in two studies conducted in Egypt [46] and Sudan [47]. One study used the CDI tool (cutoff of ≥ 24) and reported a high prevalence of depressive symptoms among adolescent females, aged 14–17 years, residing in Egypt (15.3%) [46]. Another study used the BDI tool (cut-off point ≥ 8) and reported a prevalence rate of 28.2% among adolescent females, aged 12–19 years, residing in Sudan [47].

In our review, we found that multiple factors were associated with depression and anxiety among adolescents, such as having a parent with a mental health condition, older age, and female gender. These findings are consistent with reviews from low- and middle-income countries [41,48,49]. In addition, females were more likely to develop anxiety [16,17], depression [10,16,17,19], PTSD [8], and eating disorders [14] compared to male adolescents. A systematic review examining the prevalence rate of depressive symptoms among adolescents globally, reported a higher prevalence rate among female adolescents than male adolescents (34% vs. 24%) [50]. Another factor that influenced the prevalence rate of mental health disorders was income level [51]. There was some contradiction in the findings, where two studies showed that a low-income level was associated with the increased prevalence of mental health disorders [14,19], such as depression and anxiety, while another study showed that a high family socioeconomic status increased the prevalence of eating disorders [16]. Further studies with this focus are needed to deepen the knowledge about the subject.

The high overall prevalence rates reported in this review should be viewed with caution because female adolescents were overrepresented in the total population of the included studies. Females are more likely to be exposed to risk factors such as sexual abuse [52], gender discrimination [53], and violence [54], as well as experience chronic concern with their appearance and body dissatisfaction [55], which makes them more vulnerable to developing and internalizing mental health problems [56]. Future research should clarify how gender differences affect the trajectory of mental health among children and adolescents and provide empirical evidence to healthcare specialists and policymakers to translate the knowledge of gender differences into culturally sensitive program implementation. Further, all of the included studies utilized self-reported screening tools, which are subjected to self-recall bias. Screening tools, compared to diagnostic interviews, have been shown to overestimate the prevalence rates of mental health disorders [41].

This review indicates that there has been an increase in the number of epidemiological studies examining mental health problems among adolescents in Jordan over the years. However, there remains a scarcity of studies investigating the prevalence of mental health disorders in Jordan, specifically among refugees. None of the studies assessed the prevalence of eating disorders among refugees, as well as sleeping disorders and substance use disorders among adolescents. Moreover, mental disorders’ etiologies, including the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact, and their consequences were not thoroughly examined, as well as the help-seeking behaviors among children and adolescents regarding mental health services. Additional research regarding health-related quality of life (HRQOL), and drug addiction among adolescents experiencing mental health problems should also be investigated to assess the impact of mental health disorders.

Our study is limited by the fact that only four databases were searched; therefore, studies indexed in other databases were missed during the search strategy. In addition, our search strategy might not have extracted all pertinent studies from the four databases; therefore, we might have missed some relevant studies. Moreover, the included studies all had different methodologies and target audiences and used a different sampling approach and self-reported tools to measure the prevalence of mental health issues. Therefore, our results and conclusions should be interpreted with caution.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this review has highlighted the magnitude of mental health disorders and psychosocial problems among children and adolescents. The findings should be interpreted with caution due to the heterogeneity of the studies, which was outlined in the variety of screening tools and cut-off points that were used, as well as the lack of representative samples. Several factors were associated with mental health issues. Syrians compared to Jordanian adolescents were more likely to develop anxiety symptoms. Female gender and older age were associated with higher rates of mental health problems. Further studies are needed to investigate other factors such as drug addiction, quality of life, and help-seeking behaviors among adolescents experiencing mental health issues, as well as etiologies and trajectories of mental health disorders. Future research should use a robust methodological framework to come up with thorough evidence to inform policies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A., Y.K., E.T., S.A.K. and M.A.N. methodology, R.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.A.; writing—review and editing, R.A., Y.K., E.T., S.A.K. and M.A.N.; supervision, Y.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Piao, J.; Huang, Y.; Han, C.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; He, X. Alarming Changes in the Global Burden of Mental Disorders in Children and Adolescents from 1990 to 2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 1827–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. Adolescent Health Dashboards. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/adolescent-health-dashboards-country-profiles/ (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, K.; Abd-Allah, F.; Bhutta, Z.A.; et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Mazidi, M.; Li, K.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Kirwan, R.; Zhou, H.; Yan, N.; Rahman, A.; Wang, W.; et al. Prevalence of Mental Health Problems among Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 293, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNHCR Jordan Factsheet. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/jordan/unhcr-jordan-factsheet-may-2019 (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- “Adolescent Mental Health”. Who.int. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- Yonis, O.B.; Khader, Y.; Jarboua, A.; Al-Bsoul, M.M.; Al-Akour, N.; Alfaqih, M.A.; Khatatbeh, M.M.; Amarneh, B. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among Syrian Adolescent Refugees in Jordan. J. Public Health 2020, 42, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonis, O.B.; Khader, Y.; Al-Mistarehi, A.H.; Khudair, S.A.; Dawoud, M. Behavioural and Emotional Symptoms among Schoolchildren: A Comparison between Jordanians and Syrian Refugees. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2021, 27, 1162–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehnel, R.; Dalky, H.; Sudarsan, S.; Al-Delaimy, W.K. Resilience and Mental Health Among Syrian Refugee Children in Jordan. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2022, 24, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khader, Y.; Bsoul, M.; Assoboh, L.; Al-Bsoul, M.; Al-Akour, N. Depression and Anxiety and Their Associated Factors Among Jordanian Adolescents and Syrian Adolescent Refugees. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2021, 59, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews—JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis—JBI Global Wiki. Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/4687342/Chapter+11%3A+Scoping+reviews (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, N.; Naveed, S.; Zeshan, M.; Tahir, M.A. How to Conduct a Systematic Review: A Narrative Literature Review. Cureus 2016, 8, e864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kloub, M.I.; Al-Khawaldeh, O.A.; ALBashtawy, M.; Batiha, A.M.; Al-Haliq, M. Disordered Eating in Jordanian Adolescents. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2019, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, T.Y.; Al-Domi, H.A.; Mashal, R.H.; Jibril, M.A.K. Eating Disturbances among Adolescent Schoolgirls in Jordan. Appetite 2010, 54, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malak, M.Z.; Khalifeh, A.H. Anxiety and Depression among School Students in Jordan: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Predictors. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2018, 54, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alslman, E.T.; Baker, N.A.; Dalky, H. Mood and Anxiety Disorders among Adolescent Students in Jordan. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2017, 23, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfoukha, M.M.; Hamdan-Mansour, A.M.; Banihani, M.A. Social and Psychological Factors Related to Risk of Eating Disorders Among High School Girls. J. Sch. Nurs. 2019, 35, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dardas, L.A.; Silva, S.G.; Smoski, M.J.; Noonan, D.; Simmons, F.L.A. The Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms among Arab Adolescents: Findings from Jordan. Public Health Nurs. 2018, 35, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousa, T.Y.; Mashal, R.H.; Al-Domi, H.A.; Jibril, M.A. Body Image Dissatisfaction among Adolescent Schoolgirls in Jordan. Body Image 2010, 7, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardas, L.A.; Silva, S.G.; Smoski, M.J.; Noonan, D.; Simmons, L.A. Adolescent Depression in Jordan Symptoms Profile, Gender Differences, and the Role of Social Context. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2018, 56, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, M.A.; Al Bashtawy, M.; Tubaishat, A.; Batiha, A.-M.; Tawalbeh, L. Prevalence of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder among School-Aged Children in Jordan. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2017, 23, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAzzam, M.; Abuhammad, S.; Abdalrahim, A.; Hamdan-Mansour, A.M. Predictors of Depression and Anxiety Among Senior High School Students During COVID-19 Pandemic: The Context of Home Quarantine and Online Education. J. Sch. Nurs. 2021, 37, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malak, M.Z.; Al-amer, R.M.; Khalifeh, A.H.; Jacoub, S.M. Evaluation of Psychological Reactions among Teenage Married Girls in Palestinian Refugee Camps in Jordan. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoum, M.; Alhussami, M.; Rayan, A. Emotional and Behavioral Problems among Jordanian Adolescents: Prevalence and Associations with Academic Achievement. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2018, 31, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadan, M.; Kheirallah, K.; Saleh, T.; Bellizzi, S.; Shorman, E. The Relationship Between Spirituality and Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Syrian Adolescents in Jordan. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2022, 15, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.; Panter-Brick, C.; Hadfield, K.; Dajani, R.; Hamoudi, A.; Sheridan, M. Minds Under Siege: Cognitive Signatures of Poverty and Trauma in Refugee and Non-Refugee Adolescents. Child Dev. 2019, 90, 1856–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itani, T.; Jacobsen, K.H.; Kraemer, A. Suicidal Ideation and Planning among Palestinian Middle School Students Living in Gaza Strip, West Bank, and United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) Camps. Int. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2017, 4, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nafi, O.; Shahin, A.; Tarawneh, A.; Samhan, Z. Differences in Identification of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children between Teachers and Parents. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2020, 26, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahamneh, H.; Arafa, L.; Al Orani, A.; Baqleh, R.; Trabelsi, K.; Jmaiel, M.; Khacharem, A. Long-Term Psychological Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic on Children in Jordan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardas, L.A.; Silva, S.; Noonan, D.; Simmons, L.A. A Pilot Study of Depression, Stigma, and Attitudes towards Seeking Professional Psychological Help among Arab Adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2018, 30, 20160070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan-Mansour, A.M.; AL-Sagarat, A.Y.; Shehadeh, J.H.; Al Thawabieh, S.S. Determinants of Substance Use Among High School Students in Jordan. Curr. Drug Res. Rev. 2020, 12, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sheyab, N.A.; Gharaibeh, T.; Kheirallah, K. Relationship between Peer Pressure and Risk of Eating Disorders among Adolescents in Jordan. J. Obes. 2018, 2018, 7309878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alassaf, A.; Gharaibeh, L.; Zurikat, R.O.; Farkouh, A.; Ibrahim, S.; Zayed, A.A.; Odeh, R. Prevalence of Depression in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes between 10 and 17 Years of Age in Jordan. J. Diabetes Res. 2023, 2023, 3542780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearing, R.E.; MacKenzie, M.J.; Schwalbe, C.S.; Brewer, K.B.; Ibrahim, R.W. Prevalence of Mental Health and Behavioral Problems among Adolescents in Institutional Care in Jordan. Psychiatr. Serv. 2013, 64, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearing, R.E.; Brewer, K.B.; Elkins, J.; Ibrahim, R.W.; MacKenzie, M.J.; Schwalbe, C.S.J. Prevalence and Correlates of Depression, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Suicidality in Jordanian Youth in Institutional Care. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2015, 203, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dardas, L.A.; Silva, S.G.; Scott, J.; Gondwe, K.W.; Smoski, M.J.; Noonan, D.; Simmons, L.A. Do Beliefs about Depression Etiologies Influence the Type and Severity of Depression Stigma? The Case of Arab Adolescents. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2018, 54, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, M.M.; Orvaschel, H.; Padian, N. Children’s Symptom and Social Functioning Self-Report Scales. Comparison of Mothers’ and Children’s Reports. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1980, 168, 736–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollins, K.; Mrcpsych, M.; Grayson, K.; Frss, B.A. The Mental Health and Social Circumstances of Kosovan Albanian and Albanian Unaccompanied Refugee Adolescents Living in London. Divers. Health Soc. Care 2007, 4, 277–286. [Google Scholar]

- Bean, T.; Derluyn, I.; Eurelings-Bontekoe, E.; Broekaert, E.; Spinhoven, P. Comparing Psychological Distress, Traumatic Stress Reactions, and Experiences of Unaccompanied Refugee Minors with Experiences of Adolescents Accompanied by Parents. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2007, 195, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorns-Presentati, A.; Napp, A.K.; Dessauvagie, A.S.; Stein, D.J.; Jonker, D.; Breet, E.; Charles, W.; Swart, R.L.; Lahti, M.; Suliman, S.; et al. The Prevalence of Mental Health Problems in Sub-Saharan Adolescents: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, S.; Levin, L.; Persson, L.Å.; Hägglöf, B. Stories of Pre-War, War and Exile: Bosnian Refugee Children in Sweden. Med. Confl. Surviv. 2001, 17, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soykoek, S.; Mall, V.; Nehring, I.; Henningsen, P.; Aberl, S. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Syrian Children of a German Refugee Camp. Lancet 2017, 389, 903–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, J.D.; Ajeeb, M.; Fadel, L.; Saleh, G. Mental Health in Syrian Children with a Focus on Post-Traumatic Stress: A Cross-Sectional Study from Syrian Schools. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed.—PsycNET. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1994-97698-000 (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- El-Missiry, A.; Soltan, M.; Hadi, M.A.; Sabry, W. Screening for Depression in a Sample of Egyptian Secondary School Female Students. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 136, e61–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaaban, K.M.A.; Baashar, T.A. Community Study of Depression in Adolescent Girls: Prevalence and Its Relation to Age. Med. Princ. Pract. 2003, 12, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yatham, S.; Sivathasan, S.; Yoon, R.; da Silva, T.L.; Ravindran, A.V. Depression, Anxiety, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among Youth in Low and Middle Income Countries: A Review of Prevalence and Treatment Interventions. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2018, 38, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarafshan, H.; Mohammadi, M.R.; Salmanian, M. Prevalence of Anxiety Disorders among Children and Adolescents in Iran: A Systematic Review. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2015, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey, S.; Ng, E.D.; Wong, C.H.J. Global Prevalence of Depression and Elevated Depressive Symptoms among Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 61, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, S.A.; Silva, S.U.; Ronca, D.B.; Santos Goncalves, V.S.; Dutra, E.S.; Carvalno, K.M.B. Common Mental Disorders Prevalence in Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.F. Child Sexual Abuse. Lancet 2004, 364, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigod, S.N.; Rochon, P.A. The Impact of Gender Discrimination on a Woman’s Mental Health. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 20, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, L.M.; Trevillion, K.; Agnew-Davies, R. Domestic Violence and Mental Health. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2010, 22, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report of the APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls. 2007. Available online: http://www.apa.org/pi/women/programs/girls/report-full.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Rosenfield, S.; Mouzon, D. Gender and Mental Health; Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).