Mental Health and Psychosocial Problems among Children and Adolescents in Jordan: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

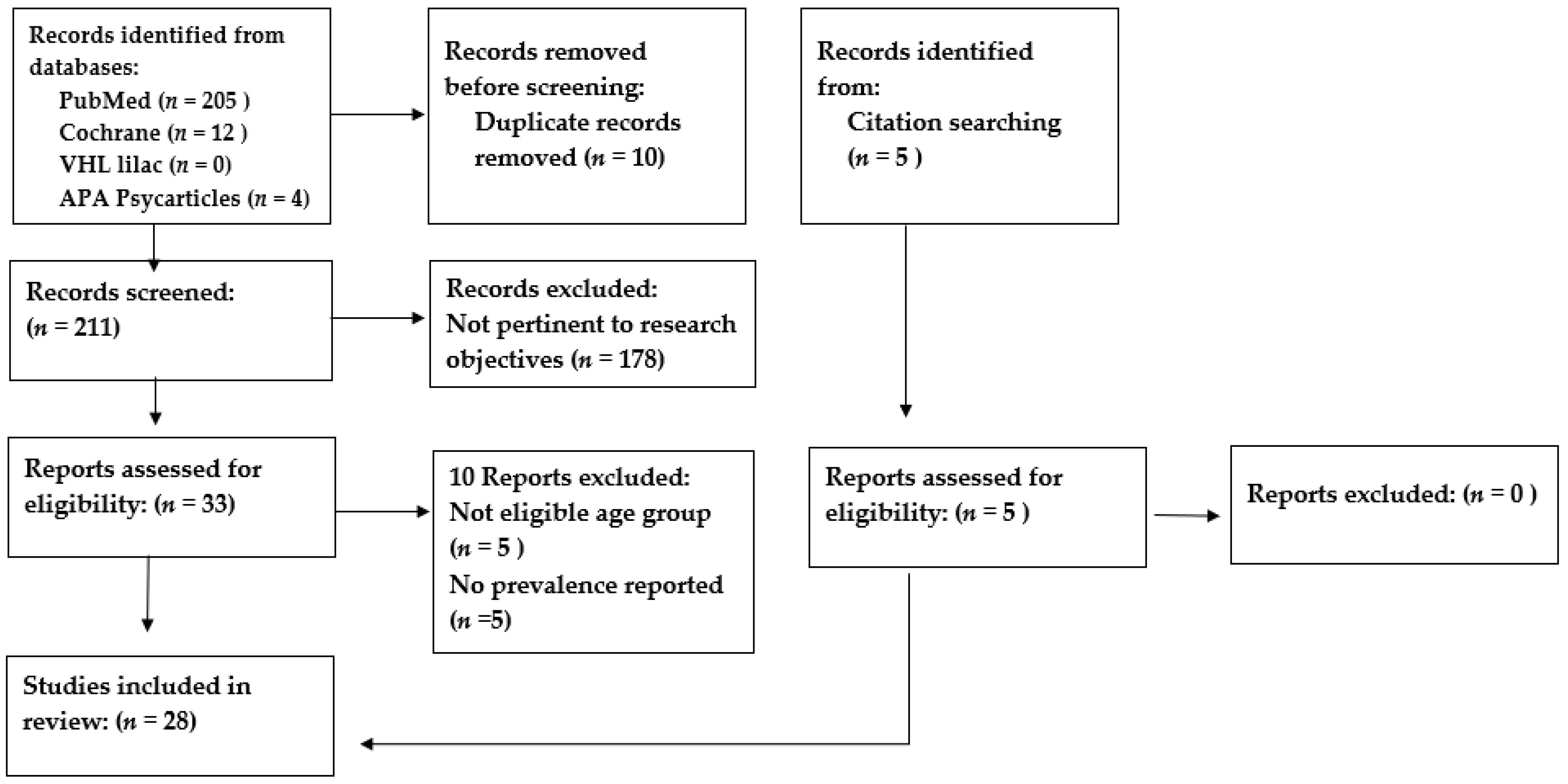

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search

- 1.

- “Mental Health” [Mesh] or “Mental illness” [tw] or “Mental Disorders” [Mesh] or anxiety[tw] or “Depression” [Mesh] or “Depressive Disorder” [Mesh] or “Psychosocial problems” [tw] or “psychiatric disorders” [tw] or "Problem Behavior” [Mesh] or “behavioral problem” [tw] or “Conduct Disorder” [Mesh] or “emotional problems” [tw] or “Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity” [Mesh] or “Adverse Childhood Experiences” [Mesh] or “Adverse childhood experiences” [tw] or fear [tw] or attention-deficit [tw] or “attention deficit” [tw] or “Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder” [Mesh] or “Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic” [Mesh] or “Intellectual Disability” [Mesh] or “Autistic Disorder” [Mesh] or “Autism Spectrum Disorder” [Mesh]

- 2.

- “Adolescent” [Mesh] or “Child” [Mesh] or child [tw]

- 3.

- “Jordan” [Mesh]

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Studies’ Characteristics

3.2. Depression

3.3. Anxiety

3.4. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Emotional and Behavioral Problems

3.5. Eating Disorders

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Piao, J.; Huang, Y.; Han, C.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; He, X. Alarming Changes in the Global Burden of Mental Disorders in Children and Adolescents from 1990 to 2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 1827–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. Adolescent Health Dashboards. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/adolescent-health-dashboards-country-profiles/ (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, K.; Abd-Allah, F.; Bhutta, Z.A.; et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Mazidi, M.; Li, K.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Kirwan, R.; Zhou, H.; Yan, N.; Rahman, A.; Wang, W.; et al. Prevalence of Mental Health Problems among Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 293, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNHCR Jordan Factsheet. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/jordan/unhcr-jordan-factsheet-may-2019 (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- “Adolescent Mental Health”. Who.int. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- Yonis, O.B.; Khader, Y.; Jarboua, A.; Al-Bsoul, M.M.; Al-Akour, N.; Alfaqih, M.A.; Khatatbeh, M.M.; Amarneh, B. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among Syrian Adolescent Refugees in Jordan. J. Public Health 2020, 42, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonis, O.B.; Khader, Y.; Al-Mistarehi, A.H.; Khudair, S.A.; Dawoud, M. Behavioural and Emotional Symptoms among Schoolchildren: A Comparison between Jordanians and Syrian Refugees. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2021, 27, 1162–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehnel, R.; Dalky, H.; Sudarsan, S.; Al-Delaimy, W.K. Resilience and Mental Health Among Syrian Refugee Children in Jordan. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2022, 24, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khader, Y.; Bsoul, M.; Assoboh, L.; Al-Bsoul, M.; Al-Akour, N. Depression and Anxiety and Their Associated Factors Among Jordanian Adolescents and Syrian Adolescent Refugees. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2021, 59, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews—JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis—JBI Global Wiki. Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/4687342/Chapter+11%3A+Scoping+reviews (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, N.; Naveed, S.; Zeshan, M.; Tahir, M.A. How to Conduct a Systematic Review: A Narrative Literature Review. Cureus 2016, 8, e864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kloub, M.I.; Al-Khawaldeh, O.A.; ALBashtawy, M.; Batiha, A.M.; Al-Haliq, M. Disordered Eating in Jordanian Adolescents. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2019, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, T.Y.; Al-Domi, H.A.; Mashal, R.H.; Jibril, M.A.K. Eating Disturbances among Adolescent Schoolgirls in Jordan. Appetite 2010, 54, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malak, M.Z.; Khalifeh, A.H. Anxiety and Depression among School Students in Jordan: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Predictors. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2018, 54, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alslman, E.T.; Baker, N.A.; Dalky, H. Mood and Anxiety Disorders among Adolescent Students in Jordan. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2017, 23, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfoukha, M.M.; Hamdan-Mansour, A.M.; Banihani, M.A. Social and Psychological Factors Related to Risk of Eating Disorders Among High School Girls. J. Sch. Nurs. 2019, 35, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dardas, L.A.; Silva, S.G.; Smoski, M.J.; Noonan, D.; Simmons, F.L.A. The Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms among Arab Adolescents: Findings from Jordan. Public Health Nurs. 2018, 35, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousa, T.Y.; Mashal, R.H.; Al-Domi, H.A.; Jibril, M.A. Body Image Dissatisfaction among Adolescent Schoolgirls in Jordan. Body Image 2010, 7, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardas, L.A.; Silva, S.G.; Smoski, M.J.; Noonan, D.; Simmons, L.A. Adolescent Depression in Jordan Symptoms Profile, Gender Differences, and the Role of Social Context. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2018, 56, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, M.A.; Al Bashtawy, M.; Tubaishat, A.; Batiha, A.-M.; Tawalbeh, L. Prevalence of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder among School-Aged Children in Jordan. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2017, 23, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAzzam, M.; Abuhammad, S.; Abdalrahim, A.; Hamdan-Mansour, A.M. Predictors of Depression and Anxiety Among Senior High School Students During COVID-19 Pandemic: The Context of Home Quarantine and Online Education. J. Sch. Nurs. 2021, 37, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malak, M.Z.; Al-amer, R.M.; Khalifeh, A.H.; Jacoub, S.M. Evaluation of Psychological Reactions among Teenage Married Girls in Palestinian Refugee Camps in Jordan. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoum, M.; Alhussami, M.; Rayan, A. Emotional and Behavioral Problems among Jordanian Adolescents: Prevalence and Associations with Academic Achievement. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2018, 31, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadan, M.; Kheirallah, K.; Saleh, T.; Bellizzi, S.; Shorman, E. The Relationship Between Spirituality and Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Syrian Adolescents in Jordan. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2022, 15, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.; Panter-Brick, C.; Hadfield, K.; Dajani, R.; Hamoudi, A.; Sheridan, M. Minds Under Siege: Cognitive Signatures of Poverty and Trauma in Refugee and Non-Refugee Adolescents. Child Dev. 2019, 90, 1856–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itani, T.; Jacobsen, K.H.; Kraemer, A. Suicidal Ideation and Planning among Palestinian Middle School Students Living in Gaza Strip, West Bank, and United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) Camps. Int. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2017, 4, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nafi, O.; Shahin, A.; Tarawneh, A.; Samhan, Z. Differences in Identification of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children between Teachers and Parents. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2020, 26, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahamneh, H.; Arafa, L.; Al Orani, A.; Baqleh, R.; Trabelsi, K.; Jmaiel, M.; Khacharem, A. Long-Term Psychological Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic on Children in Jordan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardas, L.A.; Silva, S.; Noonan, D.; Simmons, L.A. A Pilot Study of Depression, Stigma, and Attitudes towards Seeking Professional Psychological Help among Arab Adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2018, 30, 20160070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan-Mansour, A.M.; AL-Sagarat, A.Y.; Shehadeh, J.H.; Al Thawabieh, S.S. Determinants of Substance Use Among High School Students in Jordan. Curr. Drug Res. Rev. 2020, 12, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sheyab, N.A.; Gharaibeh, T.; Kheirallah, K. Relationship between Peer Pressure and Risk of Eating Disorders among Adolescents in Jordan. J. Obes. 2018, 2018, 7309878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alassaf, A.; Gharaibeh, L.; Zurikat, R.O.; Farkouh, A.; Ibrahim, S.; Zayed, A.A.; Odeh, R. Prevalence of Depression in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes between 10 and 17 Years of Age in Jordan. J. Diabetes Res. 2023, 2023, 3542780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearing, R.E.; MacKenzie, M.J.; Schwalbe, C.S.; Brewer, K.B.; Ibrahim, R.W. Prevalence of Mental Health and Behavioral Problems among Adolescents in Institutional Care in Jordan. Psychiatr. Serv. 2013, 64, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearing, R.E.; Brewer, K.B.; Elkins, J.; Ibrahim, R.W.; MacKenzie, M.J.; Schwalbe, C.S.J. Prevalence and Correlates of Depression, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Suicidality in Jordanian Youth in Institutional Care. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2015, 203, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dardas, L.A.; Silva, S.G.; Scott, J.; Gondwe, K.W.; Smoski, M.J.; Noonan, D.; Simmons, L.A. Do Beliefs about Depression Etiologies Influence the Type and Severity of Depression Stigma? The Case of Arab Adolescents. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2018, 54, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, M.M.; Orvaschel, H.; Padian, N. Children’s Symptom and Social Functioning Self-Report Scales. Comparison of Mothers’ and Children’s Reports. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1980, 168, 736–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollins, K.; Mrcpsych, M.; Grayson, K.; Frss, B.A. The Mental Health and Social Circumstances of Kosovan Albanian and Albanian Unaccompanied Refugee Adolescents Living in London. Divers. Health Soc. Care 2007, 4, 277–286. [Google Scholar]

- Bean, T.; Derluyn, I.; Eurelings-Bontekoe, E.; Broekaert, E.; Spinhoven, P. Comparing Psychological Distress, Traumatic Stress Reactions, and Experiences of Unaccompanied Refugee Minors with Experiences of Adolescents Accompanied by Parents. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2007, 195, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorns-Presentati, A.; Napp, A.K.; Dessauvagie, A.S.; Stein, D.J.; Jonker, D.; Breet, E.; Charles, W.; Swart, R.L.; Lahti, M.; Suliman, S.; et al. The Prevalence of Mental Health Problems in Sub-Saharan Adolescents: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, S.; Levin, L.; Persson, L.Å.; Hägglöf, B. Stories of Pre-War, War and Exile: Bosnian Refugee Children in Sweden. Med. Confl. Surviv. 2001, 17, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soykoek, S.; Mall, V.; Nehring, I.; Henningsen, P.; Aberl, S. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Syrian Children of a German Refugee Camp. Lancet 2017, 389, 903–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, J.D.; Ajeeb, M.; Fadel, L.; Saleh, G. Mental Health in Syrian Children with a Focus on Post-Traumatic Stress: A Cross-Sectional Study from Syrian Schools. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed.—PsycNET. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1994-97698-000 (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- El-Missiry, A.; Soltan, M.; Hadi, M.A.; Sabry, W. Screening for Depression in a Sample of Egyptian Secondary School Female Students. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 136, e61–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaaban, K.M.A.; Baashar, T.A. Community Study of Depression in Adolescent Girls: Prevalence and Its Relation to Age. Med. Princ. Pract. 2003, 12, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yatham, S.; Sivathasan, S.; Yoon, R.; da Silva, T.L.; Ravindran, A.V. Depression, Anxiety, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among Youth in Low and Middle Income Countries: A Review of Prevalence and Treatment Interventions. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2018, 38, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarafshan, H.; Mohammadi, M.R.; Salmanian, M. Prevalence of Anxiety Disorders among Children and Adolescents in Iran: A Systematic Review. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2015, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey, S.; Ng, E.D.; Wong, C.H.J. Global Prevalence of Depression and Elevated Depressive Symptoms among Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 61, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, S.A.; Silva, S.U.; Ronca, D.B.; Santos Goncalves, V.S.; Dutra, E.S.; Carvalno, K.M.B. Common Mental Disorders Prevalence in Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.F. Child Sexual Abuse. Lancet 2004, 364, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigod, S.N.; Rochon, P.A. The Impact of Gender Discrimination on a Woman’s Mental Health. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 20, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, L.M.; Trevillion, K.; Agnew-Davies, R. Domestic Violence and Mental Health. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2010, 22, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report of the APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls. 2007. Available online: http://www.apa.org/pi/women/programs/girls/report-full.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Rosenfield, S.; Mouzon, D. Gender and Mental Health; Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Name of the Tool | Main Outcome(s) Studied |

|---|---|

| The Child Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Scale (CPSS) | Post traumatic stress disorder |

| PTSD checklist—Civilian Version (PCL-C) | Post traumatic stress disorder |

| The Child Revised Impact of Events Scale | Post traumatic stress disorder |

| The University of California, Los Angeles, PTSD Index for DSM-IV (UPID) | Post traumatic stress disorder and exposure to traumatic events |

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies—Depression Scale (CES-D) | Depression (levels of depressive symptoms) |

| The Center for Epidemiologic Studies—Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC) | Depression (levels of depressive symptoms) |

| Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents (PHQ-A) | Mood disorders (major depressive, dysthymic, and minor depressive disorders) Anxiety disorders (panic and generalized anxiety disorders) |

| Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (Modified version of PHQ-A) | Depression (significant levels of depressive symptoms) |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD) | Anxiety |

| The Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire | Behavioral and emotional symptoms (emotional problems conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer problems, and prosocial behavior). |

| Symptom Checklist Anxiety | Anxiety |

| Eating Attitude Test (EAT-26) | Eating disorders |

| Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) | Body shape dissatisfaction |

| Eating Habits Questionnaire | Eating disorders |

| Beck’s Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) | Depression |

| Children’s Depression Inventory 2 (CDI) | Depression |

| Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale | Depression, anxiety and stress |

| Attention Deficit Disorder Evaluation Scale (ADDES)—school version and parental questionnaire | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (inattentive, hyperactive–impulsive, and combined subtypes) |

| Arabic version of the DSM-IV rating scale for the diagnosis and classification of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (inattentive, hyperactive–impulsive, and combined subtypes) |

| Child Behavioral Checklist (CBCL) |

Item 18: “I deliberately try to hurt or kill myself” |

| Author, Publication Year | Study Design | Study Population | Sample Size | Prevalence Rate | Associated Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yonis, B. et al. 2020 [7] | Cross-sectional | Syrian schoolchildren aged 12–18 years enrolled in schools of four cities: Mafraq, Sahab, Ramtha, and Zarqa. Mean age 14.5 (SD = 1.5) years. | 1768 (991 females and 777 males) |

| Having lost at least one parent (OR = 1.7 (95% CI 1.2–2.5)) and female gender (OR = 1.5 (95% CI 1.2–1.9)) were associated with increased odds of moderate to severe PTSD |

| Yonis, B. et al. 2021 [8] | Cross-sectional | Jordanian schoolchildren and Syrian refugee schoolchildren, aged 12–17 years, enrolled at schools in Mafraq, Ramtha, and Zarqa. Mean age 14.7 (SD = 1.6) years. | 3645 schoolchildren (1877 Jordanian and 1768 Syrian schoolchildren refugees (females 2013; males 1632) | Abnormally high total difficulty score of 55.2% (58.2% among refugees and 52.5% among Jordanians), peer relationship problems (53.6% of Jordanians and 55.5% of Syrians), conduct problems (47.6% among refugees and 44.8% among Jordanians), emotional symptoms (32.0% among refugees and 30.8% among Jordanians), hyperactivity/inattention problems (35.5% among refugees and 36.9% among Jordanians), and prosocial behavior problems (42.5% among refugees and 43.0% among Jordanians) | Syrian adolescents were more likely to develop overall difficulty problems (OR: 1.431, 95% CI: 1.071–1.912) and emotional symptoms (OR: 1.156, 95% CI: 1.007–1.326) and were less likely to develop peer relationship problems (OR: 0.791, 95% CI: 0.631–0.992). Those who had a history of parental death scored significantly higher on the overall difficulties, emotional symptoms, and conduct problems scales. School children who experienced parental separation had significantly more peer relationship problems (71.5%) and more prosocial behavior problems (54.4%) than those with parental death (60.2% and 40.4%, respectively) and who lived with both parents (52% and 41.5%, respectively). |

| Dehnel, Rebecca. et al. 2022 [9] | Cross-sectional | Syrian refugee children aged 10–17 living within the Jordanian community in Irbid and Ramtha. Mean age 13.4 years | 339 (85 males, 252 females, and 2 unreported) | A slight majority of children (51.8%) met the criteria for having significant depressive symptoms (cut-off score of 13), and 40.4% met the cut-off score of 16. All children (100%) have been exposed to at least one traumatic event (car accidents, robberies, and war experience). In total, 27.8% of children experienced suicidal ideation |

|

| Khader, Y. et al. 2021 [10] | Cross-sectional | Jordanian and Syrian refugee adolescents aged 12–17 years, who were registered at schools in four cities, Mafraq, Sahab, Ramtha, and Zarqa. Mean age 14.8 (SD = 1.8) for the Jordanian adolescents and 14.5 (SD = 1.5) for the Syrian adolescents |

|

| Jordanian female adolescents (OR:1.6, 85% CI: 1.2–2.1), Syrian female adolescents (OR:1.4, 85% CI: 1.4–2.5), not feeling safe among Jordanians (OR:2.2, 85% CI: 1.5–3.4) and Syrians (OR:1.8, 85% CI: 1.2–2.8), not having resilient traits among Jordanians (OR:1.9, 85% CI:1.4–2.6) and Syrians (OR:1.8, 85% CI:1.3–2.4), having high emotional symptoms among Jordanians (OR:1.9, 85% CI:1.4–2.6) and Syrians (OR:1.9, 85% CI: 1.4–2.6), and high peer relation problems among Jordanians (OR:1.6, 85% CI: 1.2–2.2) and Syrians (OR:1.4, 85% CI: 1.0–1.8) were associated with higher odds of depressive symptoms |

| Al-Kloub, I. et al. 2019 [14] | Cross-sectional | Jordanian school children aged 15–18 years attending public secondary schools in Amman, Al-Zarqa, and Al-Karak. Mean age 16.01 (SD = 0.72) years | 963 (460 males and 503 females) | Disordered eating (40.4%) and body shape dissatisfaction (16.8%) | Female gender (OR:1.30 95% CI: 1.0–1.92), urban residence (OR:3.70 (2.68–4.47), excess weight (OR:1.86 (1.2–3.88), distorted perception of weight (OR:5.08 (1.39–11.80), body shape dissatisfaction (OR:4.67 (3.10–7.03), parents’ influence (OR:1.29 (1.10–2.60), peers’ influence (OR:1.55 (1.34–2.18), and mass media influence (OR:2.30 (1.42–3.93) were associated with disordered eating |

| Mousa, Y. et al. 2010 [15] | Cross-sectional | Adolescents’ schoolgirls aged 10–16 years attending elementary public and private schools in Amman. Mean age 12.9 (SD = 1.8) years | 326 females | Eating disorders (33.4%) bulimia nervosa (0.6%), binge eating disorders (1.8%), and eating disorders not otherwise specified (31%) | Participants who had dwelling relatives (RR: 2.2 (0.99–4.8)), and friends with an ED history (RR: 3.9 (1.0–15.6)) were at a significantly higher risk of having an ED. The likelihood of developing an ED significantly increased among participants who had body image dissatisfaction (RR: 5.2 (3.3–8.4)), who were post-menarcheal (RR: 1.6 (1.4–1.9)), and overweight or at risk of being overweight (RR: 1.91 (1.4–2.6)) |

| Malak, M. et al. 2018 [16] | Cross-sectional | Jordanian school children aged 12–18 years attended public schools in Amman. Mean age 14.92 (SD = 1.69) years | 800 (400 females and 400 males). | Anxiety (42.1%) and depression (73.8%) | Age 16 to younger than 17 years, female gender, and a family income of <JD 250 were associated with a higher prevalence of anxiety. Medium or poor academic achievement and having a severe level of Internet addiction were associated with anxiety and depression |

| Alslman, E. et al. 2017 [17] | Cross-sectional | Adolescent students aged 13–18 years attending public schools in Irbid. Mean age 15.27 (SD = 0.937) years. | 1103 (605 females; 498 males) |

| Females (OR = 2.4; 95% CI: 1.77–3.25), older students (OR = 1.34; 95% CI: 1.15–1.57), and students whose parents (one or both) had mental disorders (OR = 4.67; 95% CI: 2.85–7.65) were more likely to suffer from mental disorders. Students who were living with one parent or people other than their parents were less likely to have mental disorders than those who were living with both parents (OR = 0.15; 95% CI: 0.03–0.85) |

| Alfoukha, M. 2019 [18] | Cross-sectional | High schoolgirls aged 16–18 years from governmental and private schools in the central region of Jordan. Mean age 16.9 (SD = 0.61) years. | 799 females |

| The risk of eating disorders had a significant and positive correlation with body shape dissatisfaction (r = 0.41), self-esteem (r = 0.19), psychological distress (r = 0.15), and pressure from family (r = 0.27), peers (r = 0.26), and the media (0.23). |

| Dardas, A. et al. 2018 [19] | cross-sectional, | Nationally representative school sample of Jordanian adolescents aged 12–17 attending private or public school. Mean age 15.0 years (SD = 1.5) | 2349 (1389 females; 960 males) | Approximately 47% with minimal depression, 18% with mild depression, 19% with moderate depression, and 15% with severe depression. The prevalence of moderate to severe depression scores was 34% | The mean severity of depression total scores was significantly higher in the following groups of adolescents: females; those aged 14 and older; those residing in families with monthly incomes less than JD 300 (USD 423); those reporting a chronic health problem; those reporting a mental health problem; those reporting a learning difficulty; those reporting a psychiatric diagnosis; and those reporting seeking psychological help in the past |

| Dardas, A et al. 2018 [37] | |||||

| Mousa, Y. et al. 2010 [20] | Cross-sectional | Adolescents schoolgirls, aged 10–16 years, attending public and private schools in Amman. Mean age of 12.9 (SD = 1.8) years | 326 females | Approximately 21.2% of participants displayed body image dissatisfaction (BID), and 40.5% of adolescent girls had negative eating attitudes | Participants who were overweight or at risk of being overweight (RR: 2.8 (2.1–3.8)_ and engaged in negative eating attitudes (RR: 3.6 (2.9–4.5)) were at a significantly higher risk of developing BID. Living in a Western country is inversely associated with BID (RR: 0.34 (0.12–1.1)). Media influence, such as exercise or going on a diet to lose weight because of a magazine article or picture (OR:1.6, 95% CI: 1.3–1.9) and making efforts to look like females in the media (1.2, 1.1–1.4), were associated with BID. Pressure from parents (1.9, 1.6–2.3) and peers (peer pressure) (1.6, 1.3–1.98) were associated with the increased rate of BID |

| Dardas, A. et al. 2021 [21] | Cross-sectional | Jordanian adolescents aged 12 to 17 using a nationally representative school survey | 2349 (1389 females; 960 males) | Approximately 41% of girls and 26% of boys reported scores indicating moderate to severe depression | Among female adolescents, the severity of depression total scores was significantly related to the following characteristics: age, family monthly income, mental health problems, and learning difficulties. Male adolescents’ depression scores were significantly related to their age, mental health problems, and learning difficulties |

| Al Azzam, M. et al. 2017 [22] | Cross-sectional | Jordanian adolescents aged 6–12 years enrolled in public primary schools in Mafraq | 480 (250 males; 230 females) | The prevalence of ADHD* was 40.62%. The prevalence rates within the inattentive, hyperactive–impulsive, and combined subtypes were 10.83, 9.58, and 20.21%, respectively. | Older children, boys, and increased family size were associated with the increased prevalence of ADHD symptoms. |

| AlAzzam, M. et al. 2021 [23] | Cross-sectional | Senior high school students aged 17–18 years old | 384 (153 males; 230 females) | The prevalence of mild to severe depression was 72.4%, while the prevalence of moderately severe depression was 16.9% and 14.6% for severe depression. The prevalence of mild to severe levels of anxiety was 74.9%, while 16.7% reported having severe anxiety and 58.1% reported mild to moderate levels of anxiety | Females and non-working students were associated with higher scores for depression. Females and non-working students reported higher anxiety mean scores |

| Malakeh M. et al. 2021 [24] | Cross-sectional | Teenage Palestinian married girls residing in Palestinian refugee camps, aged 14–18 years. Mean age 16.9, (SD = 0.96) years | 205 females | Approximately 39.6%, 35.6%, and 9.8% suffered moderate to extremely severe levels of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms, respectively. | Age, exposure to previous trauma and parents’ educational level were associated with all mental health symptoms |

| Atoum M. et al. 2018 [25] | Cross-sectional | Jordanian adolescents attending two public secondary schools located in Amman, aged 14–16 years. Mean age 15.12 years (SD = 0.80). | 810 (374 males; 436 females). | The overall prevalence of emotional and behavioral problems was 11.7%. The prevalence of emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, prosocial behavior, and peer problems was 14.2%, 12.5%, 7.5%, 4.2%, and 5.7%, respectively | Lower academic achievement was correlated with greater emotional and behavioral problems |

| Ramadan M. et al. 2022 [26] | Cross-sectional | Syrian adolescents who attended Jordanian schools in the northern region, aged 12–17 years. Mean age 14.89 (SD = 1.34) | 418 | The prevalence rates of moderate and severe levels of PTSD were 46.9% and 29.7%, respectively | Spirituality levels were not associated with PTSD severity levels |

| Chen, A. et al. 2019 [27] | Cross-sectional | Syrian refugee and Jordanian non-refugee adolescents enrolled through a Mercy Corp registry, aged 12–18 years. Mean age 14.29 (SD = 1.79) | 450 (240 Syrian refugees; 210 Jordanian non-refugees) (189 females; 261 males) | The prevalence of PTSD was 65.1% among the Syrian refugee adolescents and 16.2% among the Jordanian non-refugee adolescents | - |

| Itani, T. et al. 2017 [28] | Cross-sectional | Palestinian students aged 13–15 years residing in the Occupied Palestinian Territory and United Nations Relief Works Agency camps (UNRWA) | Total n = 14303, 1495 from Jordan | Suicidal ideation was assessed by one item: “During the past 12 months did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?” Suicidal planning was assessed by one item: “During the past 12 months, did you make a plan about how you would attempt suicide?” In the Jordanian UNRWA camps, the prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicidal planning was 21.7% and 18.1%, with a pooled global prevalence of 19.9% and 17.1%, respectively. The prevalence of suicidal thinking (ideation/planning) was 27.0% with a pooled global rate of 25.6% | A history of marijuana use (OR 5.1 95% CI 2.9–10.6), no close friends (OR 2.9 95% CI 2.0–4.2), recent tobacco use (OR 3.2 95% CI 2.5–4.1), food insecurity (OR 2.4 95% CI 1.7–3.6), and being bullied recently (OR 2.1 95% CI 1.6–2.6) were associated with higher odds of having suicidal ideation/planning in Jordan |

| Nafi, O. et al. 2020 [29] | Cross-sectional | Adolescents attending a total of three schools in Amman and Karak, aged 6–12 years | 1326 students (712 males; 614 females) | The prevalence of ADHD and its subtypes as reported by teachers and parents are the following: ADHD (19.2% vs. 13.0%), attention deficit (7.3% vs. 4.5%), hyperactive–impulsive (7.8% vs. 6.4%), and combined (4.2% vs. 2.1%), respectively | - |

| Al Rahamneh, H. 2021 [30] | Cross-sectional (online survey) | Parents with children between the ages of 5 and 11 years old | 1309 parents (593 with female children; 716 with male children) | According to parents’ reports, children were more irritable (66%), more likely to argue with the rest of their family (60.7%), be nervous (54.8%), reluctant (54.2%), lonely (52.4%), angry (51.8%), restless (48.6%), cry easily (47.3%), have difficulty concentrating (46.1%), be anxious (44.8%), dependent on parents (44.2%), sad (43.4%), uneasy (42.9%), frustrated (42.7%), worried (38.7%), and were afraid of COVID-19 infection (38.6%) during the lockdown compared to the pre-COVID-19 period | The child’s age, parental marital status, and fathers’ employment status were associated with emotional and behavioral differences before and during the COVID-19 pandemic |

| Dardas, L. et al. 2018 [31] | Cross-sectional | Adolescents aged 12–17 years (pilot study) | 88 (35 females; 53 males) | The prevalence of mild, moderate, and severe depression were 22%, 19%, and 24%, respectively. | Females experienced significantly higher levels of depression than males |

| Hamdan-Mansour, A. et al. 2020 [32] | Cross-sectional | Adolescents enrolled in public high schools in the central district of Jordan, aged 13–19 years | 1497 (753 females; 744 males) | Approximately 8.5% used stimulants, 12.8% used tranquilizer sedatives, 14.2% used hypnotic agents, 5.5% used antidepressant agents, 18.3% smoked cigarettes, and 31.4% smoked water pipes | High psychological stress, low coping efficacy, and low perceived social support from family were associated with a higher risk of substance use |

| Al-Sheyab Nihaya, A. et al. 2018 [33] | Cross-sectional | Jordanian school children attending private or public schools in Northern Jordan, aged 14 years to 16 years old, from both genders from grades 8 to 10. Mean age (SD) 15.06 (0.8) years | 738 (408 females; 330 males) | The prevalence of disordered eating behavior (DEB) was 23.6% (29.4% among females and 16.4% among males, p < 0.000) | - |

| Alassaf, Abeer et al. 2023 [34] | Cross-sectional | Adolescents aged 10–17 years with type 1 diabetes. Mean age of 13.7 ± 2.3 years | 108 (49 males; 59 females) | Approximately 50 (46.3%) adolescents had a depression score of 15 or more on the CES-DC, indicating significant depressive symptoms | Girls were more likely to have a depression score of 15 or more compared to boys (OR = 3.41, p = 0.025). Patients who rarely self-monitored their blood glucose levels were more likely to have a depression score of 15 or more compared to those who tested regularly (OR = 36.57, p = 0.002) |

| Gearing, Robin E. et al. 2013 [35] | Cross-sectional | Jordanian adolescents residing in four institutional care centers. Mean age was 12.26 (SD = 2.2 years) | 70 (39 males; 31 females) | Approximately 53% experienced mental health problems, and 43% and 46% had high internalizing and externalizing scores, respectively | Male gender, care entry because of maltreatment, time in care, and transfers were the most significant predictors of problems |

| Gearing, Robin E et al. 2015 [36] | Cross sectional | Jordanian children aged 7–18 years residing in five institutional care centers | 86 (41 Females; 45 males) | 45% had depression, 24% had PTSD, and 27% had suicidality | Youths who reported abuse were 5.9 times more likely to suffer from PTSD compared to youths who did not report abuse. Youths who reported having close peer relationships had 93% and 88% lower odds of PTSD and depression, respectively, compared to youths who did not report having close peer relationships |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

AlHamawi, R.; Khader, Y.; Abu Khudair, S.; Tanaka, E.; Al Nsour, M. Mental Health and Psychosocial Problems among Children and Adolescents in Jordan: A Scoping Review. Children 2023, 10, 1165. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10071165

AlHamawi R, Khader Y, Abu Khudair S, Tanaka E, Al Nsour M. Mental Health and Psychosocial Problems among Children and Adolescents in Jordan: A Scoping Review. Children. 2023; 10(7):1165. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10071165

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlHamawi, Rana, Yousef Khader, Sara Abu Khudair, Eizaburo Tanaka, and Mohannad Al Nsour. 2023. "Mental Health and Psychosocial Problems among Children and Adolescents in Jordan: A Scoping Review" Children 10, no. 7: 1165. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10071165

APA StyleAlHamawi, R., Khader, Y., Abu Khudair, S., Tanaka, E., & Al Nsour, M. (2023). Mental Health and Psychosocial Problems among Children and Adolescents in Jordan: A Scoping Review. Children, 10(7), 1165. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10071165