Abstract

Uveal melanoma (UM) is a rare disease, but the most common primary intraocular cancer, mostly localized in the choroid. Currently, the first-line treatment options for UM are radiation therapy, resection, and enucleation. However, although these treatments could potentially be curative, half of all patients will develop metastatic disease, whose prognosis is still poor. Indeed, effective therapeutic options for patients with advanced or metastatic disease are still lacking. Recently, the development of new treatment modalities with a lower incidence of adverse events, a better disease control rate, and new therapeutic approaches, have merged as new potential and promising therapeutic strategies. Additionally, several clinical trials are ongoing to find new therapeutic options, mainly for those with metastatic disease. Many interventions are still in the preliminary phases of clinical development, being investigated in phase I trial or phase I/II. The success of these trials could be crucial for changing the prognosis of patients with advanced/metastatic UM. In this systematic review, we analyzed all emerging and available literature on the new perspectives in the treatment of UM and patient outcomes; furthermore, their current limitations and more common adverse events are summarized.

1. Introduction

Uveal melanoma (UM) is a rare disease (5% of all melanomas), but the most common primary intraocular cancer in adults (mean age of 60) [1,2]. It is more frequent in Caucasians, with an incidence of 0.69 per 100,000 person-year for males and 0.54 per 100,000 person-year for females. In Europe, UM incidence increases with latitude and range from 2/106 in Spain and Italy, 4–6/106 in Central Europe, and >8/106 in Denmark and Norway [1,3].

UM develops most often in individuals with fair skin, light eye color, ocular or oculodermal melanocytosis, cutaneous or iris, or choroidal nevus. Even if it is frequently associated with BAP1 or BRCA1 mutation carriers [1], its pathogenesis is not yet clearly understood [2]. The choroid is the most frequent localization (85–91%), whereas the ciliary body or the iris are affected in only 9–15% of cases [3]. However, iris melanomas is often detected early, resulting in the best prognosis [4], while ciliary body melanomas are associated with the worst prognosis [5]. Half of all patients with UM will develop metastatic disease, whose prognosis is still poor (6–12 months of survival) [6,7].

Based on the conclusions from the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS) [7], globe–vision-preserving radiation therapy is the primary treatment of choice for most UMs nowadays in the developed world [1]. Other globe-preserving therapies may include surgical or laser. In particular, radiation therapy modalities include brachytherapy, photon-based external-beam radiation, and charged-particle radiation [8,9,10,11]. Incidentally, glucocorticoids and anti-VEGF are used for different ocular diseases [12,13,14,15,16,17], including radiation maculopathy secondary to radiotherapy for UM [18,19,20,21].

Plaque brachytherapy involves an affixing dish-shaped source of radiation onto the sclera to cover the base of the intraocular tumor. During radioactive plaque therapy, radiation travels through and is sequentially absorbed by the sclera, the tumor, the retina, the vitreous, and normal ocular structures as it exits the eye [8,9,10,11].

Prior to introduction of plaque therapy, patients with the diagnosis of UM used to be treated by enucleation (surgical removal of the eye globe) as first-line treatment, despite the critical consequences regarding vision and quality of life [22,23,24]. Therefore, the introduction of plaque therapy significantly improved the management of these patients, allowing preservation of the globe, and saving vision in selected cases. For brachytherapy, reported local recurrence rates are 14.7%—for 106Ru treatment, 7%–10% for 125I, and 3.3%—for 103Pd. Brachytherapy does not lead to increased or decreased survival rates as compared to enucleation [3,7,22].

On the other hand, photodynamic laser photocoagulation and trans-pupillary thermal therapy (TTT) reduce local recurrences by the activation of light-sensitive compounds and free radicals, directly focusing energy to the damage tumor. TTT is effective, particularly in cases of limited lesions with few risk factors. To date, no adjuvant chemotherapy allows to prolong survival [3].

Although brachytherapy is the most common globe-preserving treatment option for small- and medium-sized UM patients, the treatment is associated with severe adverse reactions. Indeed, brachytherapy can lead to the onset of radiation-induced retinopathy, cataracts, neovascular glaucoma, and macular edema, with consequent impaired vision within 2 years [3,23,25,26].

Despite the progress in the development of new therapeutic strategies for ocular tumors, to date, all treatments are still unsatisfactory in terms of disease control, as the average treatment failure in all radiation therapies is 6.15%, 18.6% in surgical, and 20.8% in laser therapies [4,27,28]. Thus, the development of new treatment modalities with a lower incidence of adverse events and a better disease control rate are highly demanded. In this regard, new therapeutic approaches emerged in recent decades, highlighting interesting pharmacological targets, such as sigma receptors [29,30].

This systematic review analyzes the data available on the therapeutic perspectives in the treatment of UM and patient outcomes; furthermore, current limitations and more common adverse events are summarized.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Methods for Identification of Studies

This systematic review was conducted and reported in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses guidelines [31]. The review protocol was not recorded at study design, and no registration number is available for consultation.

The methodology used for this comprehensive review consisted of a systematic search of all available articles exploring the current available treatments or ongoing trials on UM treatment, localized or metastatic types, in adult subjects.

A comprehensive literature search of all original articles published up to December 2020 was performed in parallel by two authors (L.G. and L.T.) using the PubMed, Cochrane library, Embase, and Scopus databases. For the search strategy, we used the following keywords and Mesh terms: “uveal melanoma”, “pharmacological treatment”, “local treatment”, and “systemic therapy”. Furthermore, the reference lists of all identified articles were examined manually to identify any potential studies that were not captured by the electronic searches.

The same terms have been used to conduct a parallel analysis on clinicaltrial.gov, to identify ongoing clinical trials.

The search workflow was designed in adherence to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement [31].

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

All studies available in the literature, reporting on original data on UM treatments, localized or metastatic types, were included, without restriction for study design, sample size, and intervention performed. Review articles, protocols, and studies without efficacy data were excluded.

2.3. Data Collection

After preparation of the list of all electronic data captured, two reviewers (M.T. and G.L.R.) examined the titles and abstracts independently and identified relevant articles according to the eligibility criteria. Any disagreement was assessed by consensus and a third reviewer (Y.A.Y.) was consulted when necessary. The reference lists of the analyzed articles were also considered as potential sources of information.

The following data were analyzed for each article, using an Excel spreadsheet:

- Study design: retrospective, prospective, comparative and non-comparative, randomized and non-randomized, open, and case report/case series;

- Clinical outcomes: primary and secondary, efficacy, safety, PK;

- Number of eyes studied, number of patients enrolled;

- Primary treatment;

- Follow-up (duration of the study);

- Main results;

- Side effects.

For unpublished data, no effort was made to contact the corresponding authors.

3. Results

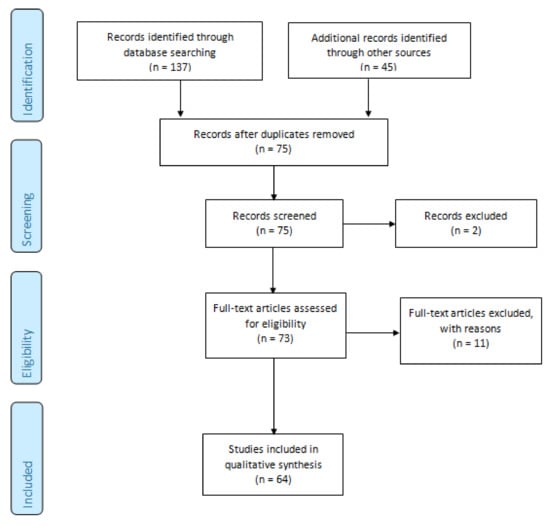

The results of the search strategy are summarized in Figure 1. From 75 articles extracted from the initial research, 73 abstracts were identified for screening and 64 of these met the inclusion/exclusion criteria for full-text review. Moreover, 11 articles were excluded, including 4 studies without efficacy data, 3 protocols, 1 without full-text, 1 non-original article (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA 2009) flowchart [18]. The 64 studies included in this systematic review were divided in the following groups: treatment of local complications (n = 3; Table 1), local treatment of primary tumor or metastases (n = 13; Table 2), and systemic therapy (n = 48; Table 3). Only one study was a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial; the other studies were phase I/pilot studies (n = 14), phase II studies (n = 34), other designs/design not available (n = 16).

Table 1.

Studies about management of local complications in patients with uveal melanoma treated with radiation-therapy.

Table 2.

Studies about local treatment of primary tumor or metastases from uveal melanoma.

Table 3.

Studies about systemic therapy of uveal melanoma.

Table 4.

Main efficacy and safety results (management of local complications).

Table 5.

Main efficacy and safety results (local treatment of primary tumor or metastases from uveal melanoma).

Table 6.

Main efficacy and safety results (systemic therapy for uveal melanoma).

No data synthesis was possible for the heterogeneity of available data and the design of the available studies (i.e., case reports or case series). Thus, the current systematic review reports a qualitative analysis, detailed issue-by-issue below in narrative fashion.

Among the 13 studies about the local treatment of the primary tumor or metastases from UM, we found 4 clinical trials—3 phase II studies and 1 phase III study. One of these trials assessed the local tumor control of the intravitreal administration of ranibizumab [33], but all patients required enucleation, and the study was terminated early due to the lack of therapeutic advantages.

Olofsson R et al. [23] observed an overall radiological response of 68% in 34 patients with liver metastasis from UM treated with isolated hepatic perfusion (IHP) within a phase II trial. The time to local progression was 7 months and the median overall survival (OS) 24 months, with a significant survival advantage compared to the control group (National Patient Register; p = 0.029). All patients enrolled in the phase II study of Fiorentini G et al. [28] obtained an objective response of liver metastasis treated with hepatic transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) adopting irinotecan-loaded microspheres. Finally, the prospective, randomized, phase III trial of Leyvraz S et al. [24] compared the IV or intra-arterial hepatic (I.a.H.) fotemustine administration in 171 patients with liver metastases from UM followed for a median of 5 years. I.a.H. did not improve OS (median 14.6 months) compared to IV administration (median 13.8 months; p = 0.59). However, there was a benefit on progression free survival (PFS) for HIA (median PFS of 4.5 versus 3.5 months, respectively; 1-year PFS rate 24% versus 8%), and on response rate (10.5% versus 2.4%).

In regard to systemic therapy, 30 phase II studies and 1 phase III were conducted. Almost half of these studies evaluated the administration of various chemotherapy regimens in advanced or metastatic UM [43,52,54,66,68,69,71,72,74,76,77,78,79].

Overall, we found a low response rate and limited advantage in terms of survival.

The study by Lane AM et al. [62] did not demonstrate an advantage of adjuvant interferon treatment in terms of melanoma-related mortality compared to historical controls in 121 patients with choroidal or ciliary body melanoma during a long-term follow-up (approximately 9 years). However, Binkley E et al. [38] recently reported a survival benefit of adjuvant therapy based on sequential low-dose dacarbazine and interferon-alpha in 33 patients with high-risk UM (5-year median OS of 66% (45–80, median not observed) in treated patients and 37% (19–55, median 54 months) in control).

The trials that assessed the role of immunotherapy in patients with unresectable or metastatic UM showed a low rate of response, a median OS of 1 year with nivolumab and pembrolizumab [35,39], and 6 months with ipilimumab [51]. One patient treated with pembrolizumab reached a complete response (CR, ongoing at 25.5 months), but the drug was stopped after the first dose due to the onset of a severe form of diabetes (grade 4).

Target therapies obtained partial response (PR) or stable disease (SD) as the best objective outcome [36,40,44,48,49,57,58,82]. No difference in PFS or OS was observed versus chemotherapy or compared with the expected patient survival [36,48,50,58,82].

The only randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial enrolled 129 patients with metastatic UM to receive either selumetinib or placebo plus dacarbazine [42]. The primary endpoint of PFS advantage was not met (median PFS was 2.8 months in the selumetinib + dacarbazine and 1.8 months in the placebo + dacarbazine group).

Finally, we found more than 140 interventional clinical trials (49 ongoing, 79 completed, 1 suspended, 4 withdrawn, and 9 with unknown status) on uveal melanoma listed on the clinicaltrials.gov database. Among the ongoing trials, 11 foresee the enrollment of patients with local disease and 38 patients with metastatic or unresectable uveal melanoma (Table 7a,b).

Table 7.

Ongoing clinical trials in patients with uveal melanoma.

4. Discussion

To date, no drugs have been specifically approved for the treatment of non-metastatic uveal melanoma.

Pharmacological treatments result ineffective, likely due to the incapacity to reach enough concentration into the tumor area in the eye, as result of the characteristics of the posterior segment and the blood–retinal barrier [96]. It is possible that local delivery at the ocular site will obtain better results, in terms of efficacy and safety. Therefore, researchers are developing new drug delivery systems for uveal melanoma and other ophthalmological diseases, thanks in part to nanotechnology [97,98,99].

However, the possibility of using effective drug delivery still represents a big challenge, and further studies are needed to establish whether this new technology could help in the fight against uveal melanoma [100,101,102,103].

Despite advances in diagnosis and local treatment, the overall survival (OS) of patients with uveal melanoma remains poor because of the progression into metastatic disease. Indeed, up to 50% of cases develop metastasis, especially in the liver, at approximately 5 years after treatment of the primary tumor [104,105,106]. This time is shorter in patients with larger neoplasm, especially in those with a higher grade of malignancy [107,108].

Metastatic disease is particularly difficult to treat; available systemic therapy rarely produces durable responses or significant survival benefits. Actually, the reported median survival after detection of metastatic disease is less than 1 year [109].

Moreover, no adjuvant therapy, which may be more active in treating microscopic metastatic tumor, was shown to reduce the risk of disease spread or survival improvement, and would need further studies [104].

The treatment of metastatic uveal melanoma includes systemic chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and molecular targeted therapy. Moreover, local therapies for liver disease (resection, chemoembolization, immunoembolization, radioembolization, isolated hepatic perfusion, percutaneous hepatic perfusion) are also recommended [110].

The most updated clinical practice guidelines [111,112] recommend the enrollment of patients with metastatic disease in clinical trials, if possible. Otherwise, systemic therapies used to treat cutaneous melanoma can be considered, although no regimens demonstrated improved overall survival in uveal disease.

Chemotherapy regimens for cutaneous melanoma (dacarbazine, temozolomide, cisplatin, paclitaxel, treosulfan, fotemustine) have been used in uveal melanoma although with unsatisfactory results (response rate 0–15%, and no survival benefit) [113,114,115].

Immunotherapy has dramatically improved outcomes for patients with advanced cutaneous melanoma, but this clinical benefit has not been observed in metastatic uveal melanoma, probably due to a low mutational burden and low PD-L1 expression [116,117,118].

The randomized phase III trial that led to the approval of ipilimumab did not include patients with uveal melanoma, and subsequent smaller studies found a low response rate (0–5%) and an OS of less than 10 months [64,119,120,121,122].

Even the phase III CheckMate-067 trial, comparing the concomitant use of nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus the monotherapy alone, excluded uveal melanoma patients [123].

A large series of patients with metastatic uveal melanoma treated with PD-1 and PD-L1 antibodies (pembrolizumab N = 38; nivolumab N = 16; atezolizumab N = 2) showed a partial response rate of 3.6%, a median progression free survival (PFS) of 2.8 months, and an OS of 7.6 months [124].

Recently, the results of a single arm phase II trial demonstrated an overall response rate (ORR) of 18%, a median PFS of 5.5 months, and a median OS of 19.1 months in 33 patients with metastatic uveal melanoma treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab [125]. Considering these results, the usefulness of immunotherapy in uveal melanoma requires additional investigation and many clinical trials are currently ongoing.

A novel bispecific molecule targeting T-cells (tebentafusp, IMCgp100) showed clinical benefit in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma in phase II, and recently, a phase III study [126].

The mechanism of action consists in the redirection of T cells to target the gp100 protein, highly expressed in melanocytes and melanoma cells. The phase III trial assessed OS as the primary endpoint in 378 naïve patients with metastatic uveal melanoma, randomized 2:1 to receive tebentafusp or the investigator’s choice among dacarbazine, ipilimumab, or pembrolizumab.

OS was statistically significantly improved in patients randomized in the experimental group compared to the control group in the first pre-planned interim analysis (OS hazard ratio of 0.51, and estimated 1-year OS rate of 73% for the study drug versus 58% with the investigator’s choice) [127,128]. These data confirm the positive survival benefit of the phase II clinical trial, and might likely support the use of this drug as a potential new treatment for cancer patients with this highly unmet need. Moreover, the drug was granted the fast-track and orphan drug designation by the FDA for uveal melanoma [129,130] and Promising Innovative Medicine designation under the UK Early Access to Medicines Scheme.

In regard to target therapies, BRAF and KIT inhibitors are not included among treatment options, as uveal melanomas usually lack BRAF and KIT mutations. Conversely, the typical mutations in GNAQ and GNA11 genes lead to constitutive activation of the MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways and therapies that target downstream effectors, such as MEK, Akt, and protein kinase C (PKC) are under investigation, even with disappointing results so far [113].

For example, selumetinib, a potent and highly selective inhibitor of MEK, associated with dacarbazine, showed no significant improvement in terms of PFS compared to dacarbazine alone (2.8 versus 1.8 months, p = 0.32) in the phase III SUMIT trial [55]. Similarly, there was no significant difference in ORR (3.1 versus 0%, p = 0.36).

According to the underlying molecular mechanisms, target therapies could probably be improved by combinatory strategies [131].

To date, several clinical trials are ongoing to find new therapeutic options, mainly for those with metastatic disease [110]. Many interventions are still in the preliminary phases of clinical development, being investigated in phase I trial or phase I/II (Table 7).

Additionally, the possibility to exploit a possible ocular pharmaceutical RNA-based treatment against differentially expressed miRNAs in different ocular diseases [132,133], including UM, together with the success of these trials, could be crucial for changing the prognosis of patients with advanced/metastatic UM.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review shows the lack of well-designed randomized clinical trials so far and confirms the limited advantages, in terms of response and survival of treatment options for UM. Despite the progress in the development of new effective therapeutic strategies, to date, all treatments for UM are still unsatisfactory and patients have a poor long-term prognosis. The future success of ongoing trials could hopefully change the outcome of patients with advanced/metastatic UM.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.L.R., M.D.T.; methodology, G.L.R., M.D.T.; formal analysis, L.G., L.T., G.L.R., M.D.T.; investigation, L.G., L.T., G.L.R., M.D.T.; resources, L.G., L.T.; data curation, L.G., L.T., M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.G., L.T., M.C., G.L.R., M.D.T.; writing—review and editing, Y.A.Y., G.L.R., M.D.T., C.B., F.D., T.A., R.R., S.Z., Y.A.Y., R.N., K.N.; supervision, G.L.R., M.D.T.; project administration, G.L.R., M.D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. G.L.R. was supported by the PON AIM R&I 2014-2020-E66C18001260007. M.D.T. was supported by the “Foundation to support the development of Ophthalmology” in Poland. The Foundation had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found here: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, (accessed on 1 February 2021); https://clinicaltrials.gov/, (accessed on 15 February 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pt, F. Intraocular melanoma. In Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology, 10th ed.; DeVita, J.V.T., Lawrence, T.S., Rosenberg, S.A., Eds.; Wolter Kluwer, Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014; pp. 1770–1779. [Google Scholar]

- Ragusa, M.; Barbagallo, C.; Statello, L.; Caltabiano, R.; Russo, A.; Puzzo, L.; Avitabile, T.; Longo, A.; Toro, M.D.; Barbagallo, D.; et al. miRNA profiling in vitreous humor, vitreal exosomes and serum from uveal melanoma patients: Pathological and diagnostic implications. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2015, 16, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, C.L.; Kaliki, S.; Furuta, M.; Mashayekhi, A.; Shields, J.A. Clinical spectrum and prognosis of uveal melanoma based on age at presentation in 8,033 cases. Retina 2012, 32, 1363–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, C.L.; Kaliki, S.; Shah, S.U.; Luo, W.; Furuta, M.; Shields, J.A. Iris melanoma: Features and prognosis in 317 children and adults. J. AAPOS 2012, 16, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oittinen, H.A.; O’Shaughnessy, M.; Cullinane, A.B.; Keohane, C. Malignant melanoma of the ciliary body presenting as extraocular metastasis in the temporalis muscle. J. Clin. Pathol. 2007, 60, 834–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kujala, E.; Makitie, T.; Kivela, T. Very long-term prognosis of patients with malignant uveal melanoma. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003, 44, 4651–4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Diener-West, M.; Earle, J.D.; Fine, S.L.; Hawkins, B.S.; Moy, C.S.; Reynolds, S.M.; Schachat, A.P.; Straatsma, B.R.; Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group. The COMS randomized trial of iodine 125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma, III: Initial mortality findings. COMS Report No. 18. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2001, 119, 969–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Brachytherapy Society—Ophthalmic Oncology Task Force; ABS—OOTF Committee. The American Brachytherapy Society consensus guidelines for plaque brachytherapy of uveal melanoma and retinoblastoma. Brachytherapy 2014, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gragoudas, E.S.; Goitein, M.; Verhey, L.; Munzenreider, J.; Urie, M.; Suit, H.; Koehler, A. Proton beam irradiation of uveal melanomas. Results of 5 1/2-year study. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1982, 100, 928–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu-Tsao, S.T.; Astrahan, M.A.; Finger, P.T.; Followill, D.S.; Meigooni, A.S.; Melhus, C.S.; Mourtada, F.; Napolitano, M.E.; Nath, R.; Rivard, M.J.; et al. Dosimetry of (125)I and (103)Pd COMS eye plaques for intraocular tumors: Report of Task Group 129 by the AAPM and ABS. Med. Phys. 2012, 39, 6161–6184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Finger, P.T. Radiation therapy for choroidal melanoma. Surv. Ophthalmol. 1997, 42, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceravolo, I.; Oliverio, G.W.; Alibrandi, A.; Bhatti, A.; Trombetta, L.; Rejdak, R.; Toro, M.D.; Trombetta, C.J. The Application of Structural Retinal Biomarkers to Evaluate the Effect of Intravitreal Ranibizumab and Dexamethasone Intravitreal Implant on Treatment of Diabetic Macular Edema. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, Y.A.; ElRimawi, A.H.; Nazzal, R.M.; Qaroot, A.F.; AlAref, A.H.; Mohammad, M.; Abureesh, O.; Rejdak, R.; Nowomiejska, K.; Avitabile, T.; et al. Coats’ disease: Characteristics, management, outcome, and scleral external drainage with anterior chamber maintainer for stage 3b disease. Medicine 2020, 99, e19623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliano, C.; Toro, M.D.; Avitabile, T.; Stella, S.; Uva, M.G. Intravitreal Steroids for the Prevention of PVR After Surgery for Retinal Detachment. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21, 4698–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reibaldi, M.; Russo, A.; Avitabile, T.; Uva, M.G.; Franco, L.; Longo, A.; Toro, M.D.; Cennamo, G.; Mariotti, C.; Neri, P.; et al. Treatment of persistent serous retinal detachment in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome with intravitreal bevacizumab during the systemic steroid treatment. Retina (Phila. Pa.) 2014, 34, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reibaldi, M.; Russo, A.; Longo, A.; Bonfiglio, V.; Uva, M.G.; Gagliano, C.; Toro, M.D.; Avitabile, T. Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment with a High Risk of Proliferative Vitreoretinopathy Treated with Episcleral Surgery and an Intravitreal Dexamethasone 0.7-mg Implant. Case Rep. Ophthalmol. 2013, 4, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reibaldi, M.; Russo, A.; Zagari, M.; Toro, M.; Grande De, V.; Cifalinò, V.; Rametta, S.; Faro, S.; Longo, A. Resolution of Persistent Cystoid Macular Edema due to Central Retinal Vein Occlusion in a Vitrectomized Eye following Intravitreal Implant of Dexamethasone 0.7 mg. Case Rep. Ophthalmol. 2012, 3, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Russo, A.; Avitabile, T.; Uva, M.; Faro, S.; Franco, L.; Sanfilippo, M.; Gulisano, S.; Toro, M.; De Grande, V.; Rametta, S.; et al. Radiation Macular Edema after Ru-106 Plaque Brachytherapy for Choroidal Melanoma Resolved by an Intravitreal Dexamethasone 0.7-mg Implant. Case Rep. Ophthalmol. 2012, 3, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayess, N.; Mruthyunjaya, P. Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Therapy for Radiation Retinopathy. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retin. 2020, 51, S44–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibel, I.; Hager, A.; Riechardt, A.I.; Davids, A.M.; Böker, A.; Joussen, A.M. Antiangiogenic or Corticosteroid Treatment in Patients With Radiation Maculopathy After Proton Beam Therapy for Uveal Melanoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 168, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, A.; Bucolo, C.; Budzynski, E.; Ward, K.W.; López, F.J. In Vivo Ocular Efficacy Profile of Mapracorat, a Novel Selective Glucocorticoid Receptor Agonist, in Rabbit Models of Ocular Disease. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 1422–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Finger, P.T.; Chin, K.J.; Duvall, G.; Palladium-103 for Choroidal Melanoma Study Group. Palladium-103 ophthalmic plaque radiation therapy for choroidal melanoma: 400 treated patients. Ophthalmology 2009, 116, 790–796.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group. The COMS randomized trial of iodine 125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma: V. Twelve-year mortality rates and prognostic factors: COMS report No. 28. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2006, 124, 1684–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straatsma, B.R. The Jules Francois Memorial lecture. The collaborative ocular melanoma study and management of choroidal melanoma. Bull. Soc. Belg. Ophtalmol. 2002, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jampol, L.M.; Moy, C.S.; Murray, T.G.; Reynolds, S.M.; Albert, D.M.; Schachat, A.P.; Diddie, K.R.; Engstrom, R.E., Jr.; Finger, P.T.; Hovland, K.R.; et al. The COMS randomized trial of iodine 125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma: IV. Local treatment failure and enucleation in the first 5 years after brachytherapy. COMS report no. 19. Ophthalmology 2002, 109, 2197–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, B.S.; Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study, G. The Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS) randomized trial of pre-enucleation radiation of large choroidal melanoma: IV. Ten-year mortality findings and prognostic factors. COMS report number 24. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2004, 138, 936–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousef, Y.A.; Al Jboor, M.; Mohammad, M.; Mehyar, M.; Toro, M.D.; Nazzal, R.; Alzureikat, Q.H.; Rejdak, M.; Elfalah, M.; Sultan, I.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Intravitreal Chemotherapy (Melphalan) to Treat Vitreous Seeds in Retinoblastoma. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 696787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, S.; AlJboor, M.; Toro, M.D.; Rejdak, R.; Nowomiejska, K.; Nazzal, R.; Mohammad, M.; Al-Hussaini, M.; Khzouz, J.; Banat, S.; et al. Management and Outcomes of Unilateral Group D Tumors in Retinoblastoma. Clin. Ophthalmol. (Auckl. N.Z.) 2021, 15, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucolo, C.; Campana, G.; Di Toro, R.; Cacciaguerra, S.; Spampinato, S. Sigma1 recognition sites in rabbit iris-ciliary body: Topical sigma1-site agonists lower intraocular pressure. J. Pharm. Exp. 1999, 289, 1362–1369. [Google Scholar]

- Longhitano, L.; Castracani, C.C.; Tibullo, D.; Avola, R.; Viola, M.; Russo, G.; Prezzavento, O.; Marrazzo, A.; Amata, E.; Reibaldi, M.; et al. Sigma-1 and Sigma-2 receptor ligands induce apoptosis and autophagy but have opposite effect on cell proliferation in uveal melanoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 91099–91111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Open Med. 2009, 3, e123–e130. [Google Scholar]

- Schefler, A.C.; Fuller, D.; Anand, R.; Fuller, T.; Moore, C.; Munoz, J.; Kim, R.S.; RRR Study Group. Randomized Trial of Monthly Versus As-Needed Intravitreal Ranibizumab for Radiation Retinopathy-Related Macular Edema: 1-Year Outcomes. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 216, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, T.G.; Latiff, A.; Villegas, V.M.; Gold, A.S. Aflibercept for Radiation Maculopathy Study: A Prospective, Randomized Clinical Study. Ophthalmol. Retin. 2019, 3, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, N.; Shields, C.L.; Mashayekhi, A.; Salazar, P.F.; Materin, M.A.; O’Regan, M.; Shields, J.A. Periocular triamcinolone for prevention of macular edema after plaque radiotherapy of uveal melanoma: A randomized controlled trial. Ophthalmology 2009, 116, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venturini, M.; Pilla, L.; Agostini, G.; Cappio, S.; Losio, C.; Orsi, M.; Ratti, F.; Aldrighetti, L.; De Cobelli, F.; Del Maschio, A. Transarterial chemoembolization with drug-eluting beads preloaded with irinotecan as a first-line approach in uveal melanoma liver metastases: Tumor response and predictive value of diffusion-weighted MR imaging in five patients. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2012, 23, 937–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olofsson, R.; Cahlin, C.; All-Ericsson, C.; Hashimi, F.; Mattsson, J.; Rizell, M.; Lindner, P. Isolated hepatic perfusion for ocular melanoma metastasis: Registry data suggests a survival benefit. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 21, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leyvraz, S.; Piperno-Neumann, S.; Suciu, S.; Baurain, J.F.; Zdzienicki, M.; Testori, A.; Marshall, E.; Scheulen, M.; Jouary, T.; Negrier, S.; et al. Hepatic intra-arterial versus intravenous fotemustine in patients with liver metastases from uveal melanoma (EORTC 18021): A multicentric randomized trial. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 742–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Iersel, L.B.; de Leede, E.M.; Vahrmeijer, A.L.; Tijl, F.G.; den Hartigh, J.; Kuppen, P.J.; Hartgrink, H.H.; Gelderblom, H.; Nortier, J.W.; Tollenaar, R.A.; et al. Isolated hepatic perfusion with oxaliplatin combined with 100 mg melphalan in patients with metastases confined to the liver: A phase I study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 40, 1557–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, A.; Chervoneva, I.; Sullivan, K.L.; Eschelman, D.J.; Gonsalves, C.F.; Mastrangelo, M.J.; Berd, D.; Shields, J.A.; Shields, C.L.; Terai, M.; et al. High-dose immunoembolization: Survival benefit in patients with hepatic metastases from uveal melanoma. Radiology 2009, 252, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huppert, P.E.; Fierlbeck, G.; Pereira, P.; Schanz, S.; Duda, S.H.; Wietholtz, H.; Rozeik, C.; Claussen, C.D. Transarterial chemoembolization of liver metastases in patients with uveal melanoma. Eur. J. Radiol. 2010, 74, e38–e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorentini, G.; Aliberti, C.; Del Conte, A.; Tilli, M.; Rossi, S.; Ballardini, P.; Turrisi, G.; Benea, G. Intra-arterial hepatic chemoembolization (TACE) of liver metastases from ocular melanoma with slow-release irinotecan-eluting beads. Early results of a phase II clinical study. Vivo 2009, 23, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Voelter, V.; Schalenbourg, A.; Pampallona, S.; Peters, S.; Halkic, N.; Denys, A.; Goitein, G.; Zografos, L.; Leyvraz, S. Adjuvant intra-arterial hepatic fotemustine for high-risk uveal melanoma patients. Melanoma Res. 2008, 18, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Iersel, L.B.; Hoekman, E.J.; Gelderblom, H.; Vahrmeijer, A.L.; van Persijn van Meerten, E.L.; Tijl, F.G.; Hartgrink, H.H.; Kuppen, P.J.; Nortier, J.W.; Tollenaar, R.A.; et al. Isolated hepatic perfusion with 200 mg melphalan for advanced noncolorectal liver metastases. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2008, 15, 1891–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Noter, S.L.; Rothbarth, J.; Pijl, M.E.; Keunen, J.E.; Hartgrink, H.H.; Tijl, F.G.; Kuppen, P.J.; van de Velde, C.J.; Tollenaar, R.A. Isolated hepatic perfusion with high-dose melphalan for the treatment of uveal melanoma metastases confined to the liver. Melanoma Res. 2004, 14, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egerer, G.; Lehnert, T.; Max, R.; Naeher, H.; Keilholz, U.; Ho, A.D. Pilot study of hepatic intraarterial fotemustine chemotherapy for liver metastases from uveal melanoma: A single-center experience with seven patients. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 6, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, R.N.; Heimann, H.; Damato, B. Neoadjuvant intravitreal ranibizumab treatment in high-risk ocular melanoma patients: A two-stage single-centre phase II single-arm study. Melanoma Res. 2020, 30, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favilla, I.; Favilla, M.L.; Gosbell, A.D.; Barry, W.R.; Ellims, P.; Hill, J.S.; Byrne, J.R. Photodynamic therapy: A 5-year study of its effectiveness in the treatment of posterior uveal melanoma, and evaluation of haematoporphyrin uptake and photocytotoxicity of melanoma cells in tissue culture. Melanoma Res. 1995, 5, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, M.; Oze, I.; Masuishi, T.; Yokota, T.; Satake, H.; Iwasawa, S.; Kato, K.; Andoh, M. Multicenter prospective phase II trial of nivolumab in patients with unresectable or metastatic mucosal melanoma. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 25, 972–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, J.J.; Olson, D.J.; Allred, J.B.; Strand, C.A.; Bao, R.; Zha, Y.; Carll, T.; Labadie, B.W.; Bastos, B.R.; Butler, M.O.; et al. Randomized Phase II Trial and Tumor Mutational Spectrum Analysis from Cabozantinib versus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Uveal Melanoma (Alliance A091201). Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 804–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piha-Paul, S.A.; Sachdev, J.C.; Barve, M.; LoRusso, P.; Szmulewitz, R.; Patel, S.P.; Lara, P.N., Jr.; Chen, X.; Hu, B.; Freise, K.J.; et al. First-in-Human Study of Mivebresib (ABBV-075), an Oral Pan-Inhibitor of Bromodomain and Extra Terminal Proteins, in Patients with Relapsed/Refractory Solid Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 6309–6319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Binkley, E.; Triozzi, P.L.; Rybicki, L.; Achberger, S.; Aldrich, W.; Singh, A. A prospective trial of adjuvant therapy for high-risk uveal melanoma: Assessing 5-year survival outcomes. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 104, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Johnson, D.B.; Bao, R.; Ancell, K.K.; Daniels, A.B.; Wallace, D.; Sosman, J.A.; Luke, J.J. Response to Anti-PD-1 in Uveal Melanoma Without High-Volume Liver Metastasis. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2019, 17, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shah, S.; Luke, J.J.; Jacene, H.A.; Chen, T.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Ibrahim, N.; Buchbinder, E.L.; McDermott, D.F.; Flaherty, K.T.; Sullivan, R.J.; et al. Results from phase II trial of HSP90 inhibitor, STA-9090 (ganetespib), in metastatic uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2018, 28, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.; Moreno, R.; Gil-Martin, M.; Cascallo, M.; de Olza, M.O.; Cuadra, C.; Piulats, J.M.; Navarro, V.; Domenech, M.; Alemany, R.; et al. A Phase 1 Trial of Oncolytic Adenovirus ICOVIR-5 Administered Intravenously to Cutaneous and Uveal Melanoma Patients. Hum. Gene 2019, 30, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal, R.D.; Piperno-Neumann, S.; Kapiteijn, E.; Chapman, P.B.; Frank, S.; Joshua, A.M.; Piulats, J.M.; Wolter, P.; Cocquyt, V.; Chmielowski, B.; et al. Selumetinib in Combination With Dacarbazine in Patients With Metastatic Uveal Melanoma: A Phase III, Multicenter, Randomized Trial (SUMIT). J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1232–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schinzari, G.; Rossi, E.; Cassano, A.; Dadduzio, V.; Quirino, M.; Pagliara, M.; Blasi, M.A.; Barone, C. Cisplatin, dacarbazine and vinblastine as first line chemotherapy for liver metastatic uveal melanoma in the era of immunotherapy: A single institution phase II study. Melanoma Res. 2017, 27, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daud, A.; Kluger, H.M.; Kurzrock, R.; Schimmoller, F.; Weitzman, A.L.; Samuel, T.A.; Moussa, A.H.; Gordon, M.S.; Shapiro, G.I. Phase II randomised discontinuation trial of the MET/VEGF receptor inhibitor cabozantinib in metastatic melanoma. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 116, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Naing, A.; Papadopoulos, K.P.; Autio, K.A.; Ott, P.A.; Patel, M.R.; Wong, D.J.; Falchook, G.S.; Pant, S.; Whiteside, M.; Rasco, D.R.; et al. Safety, Antitumor Activity, and Immune Activation of Pegylated Recombinant Human Interleukin-10 (AM0010) in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 3562–3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvajal, R.D.; Sosman, J.A.; Quevedo, J.F.; Milhem, M.M.; Joshua, A.M.; Kudchadkar, R.R.; Linette, G.P.; Gajewski, T.F.; Lutzky, J.; Lawson, D.H.; et al. Effect of selumetinib vs chemotherapy on progression-free survival in uveal melanoma: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014, 311, 2397–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjei, A.A.; LoRusso, P.; Ribas, A.; Sosman, J.A.; Pavlick, A.; Dy, G.K.; Zhou, X.; Gangolli, E.; Kneissl, M.; Faucette, S.; et al. A phase I dose-escalation study of TAK-733, an investigational oral MEK inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Investig. New Drugs 2017, 35, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mouriaux, F.; Servois, V.; Parienti, J.J.; Lesimple, T.; Thyss, A.; Dutriaux, C.; Neidhart-Berard, E.M.; Penel, N.; Delcambre, C.; Peyro Saint Paul, L.; et al. Sorafenib in metastatic uveal melanoma: Efficacy, toxicity and health-related quality of life in a multicentre phase II study. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 115, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shoushtari, A.N.; Ong, L.T.; Schoder, H.; Singh-Kandah, S.; Abbate, K.T.; Postow, M.A.; Callahan, M.K.; Wolchok, J.; Chapman, P.B.; Panageas, K.S.; et al. A phase 2 trial of everolimus and pasireotide long-acting release in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2016, 26, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Joshua, A.M.; Monzon, J.G.; Mihalcioiu, C.; Hogg, D.; Smylie, M.; Cheng, T. A phase 2 study of tremelimumab in patients with advanced uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2015, 25, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, L.; Vaubel, J.; Mohr, P.; Hauschild, A.; Utikal, J.; Simon, J.; Garbe, C.; Herbst, R.; Enk, A.; Kampgen, E.; et al. Phase II DeCOG-study of ipilimumab in pretreated and treatment-naive patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Jung, M.; Choi, H.J.; Kim, H.R.; Kim, H.S.; Roh, M.R.; Ahn, J.B.; Chung, H.C.; Heo, S.J.; Rha, S.Y.; et al. Results of a Phase II Study to Evaluate the Efficacy of Docetaxel and Carboplatin in Metastatic Malignant Melanoma Patients Who Failed First-Line Therapy Containing Dacarbazine. Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 47, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, M.A.; Gordon, M.S.; Edelman, G.; Bendell, J.C.; Kudchadkar, R.R.; LoRusso, P.M.; Johnston, S.H.; Clary, D.O.; Schwartz, G.K. Phase I study of XL281 (BMS-908662), a potent oral RAF kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Investig. New Drugs 2015, 33, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homsi, J.; Bedikian, A.Y.; Papadopoulos, N.E.; Kim, K.B.; Hwu, W.J.; Mahoney, S.L.; Hwu, P. Phase 2 open-label study of weekly docosahexaenoic acid-paclitaxel in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2010, 20, 507–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borden, E.C.; Jacobs, B.; Hollovary, E.; Rybicki, L.; Elson, P.; Olencki, T.; Triozzi, P. Gene regulatory and clinical effects of interferon beta in patients with metastatic melanoma: A phase II trial. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011, 31, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Danielli, R.; Ridolfi, R.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Queirolo, P.; Testori, A.; Plummer, R.; Boitano, M.; Calabro, L.; Rossi, C.D.; Giacomo, A.M.; et al. Ipilimumab in pretreated patients with metastatic uveal melanoma: Safety and clinical efficacy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2012, 61, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhini, A.A.; Frankel, P.; Margolin, K.A.; Christensen, S.; Ruel, C.; Shipe-Spotloe, J.; Gandara, D.R.; Chen, A.; Kirkwood, J.M. Aflibercept (VEGF Trap) in inoperable stage III or stage iv melanoma of cutaneous or uveal origin. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 6574–6581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bhatia, S.; Moon, J.; Margolin, K.A.; Weber, J.S.; Lao, C.D.; Othus, M.; Aparicio, A.M.; Ribas, A.; Sondak, V.K. Phase II trial of sorafenib in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma: SWOG S0512. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falchook, G.S.; Lewis, K.D.; Infante, J.R.; Gordon, M.S.; Vogelzang, N.J.; DeMarini, D.J.; Sun, P.; Moy, C.; Szabo, S.A.; Roadcap, L.T.; et al. Activity of the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib in patients with advanced melanoma: A phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ott, P.A.; Carvajal, R.D.; Pandit-Taskar, N.; Jungbluth, A.A.; Hoffman, E.W.; Wu, B.W.; Bomalaski, J.S.; Venhaus, R.; Pan, L.; Old, L.J.; et al. Phase I/II study of pegylated arginine deiminase (ADI-PEG 20) in patients with advanced melanoma. Investig. New Drugs 2013, 31, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mahipal, A.; Tijani, L.; Chan, K.; Laudadio, M.; Mastrangelo, M.J.; Sato, T. A pilot study of sunitinib malate in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2012, 22, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, A.M.; Egan, K.M.; Harmon, D.; Holbrook, A.; Munzenrider, J.E.; Gragoudas, E.S. Adjuvant interferon therapy for patients with uveal melanoma at high risk of metastasis. Ophthalmology 2009, 116, 2206–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, U.B.; Kauczok-Vetter, C.S.; Houben, R.; Becker, J.C. Overexpression of the KIT/SCF in uveal melanoma does not translate into clinical efficacy of imatinib mesylate. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bedikian, A.Y.; Papadopoulos, N.E.; Kim, K.B.; Vardeleon, A.; Smith, T.; Lu, B.; Deitcher, S.R. A pilot study with vincristine sulfate liposome infusion in patients with metastatic melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2008, 18, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjei, A.A.; Cohen, R.B.; Franklin, W.; Morris, C.; Wilson, D.; Molina, J.R.; Hanson, L.J.; Gore, L.; Chow, L.; Leong, S.; et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the oral, small-molecule mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) in patients with advanced cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 2139–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schmittel, A.; Schmidt-Hieber, M.; Martus, P.; Bechrakis, N.E.; Schuster, R.; Siehl, J.M.; Foerster, M.H.; Thiel, E.; Keilholz, U. A randomized phase II trial of gemcitabine plus treosulfan versus treosulfan alone in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. Ann. Oncol. 2006, 17, 1826–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richtig, E.; Langmann, G.; Schlemmer, G.; Mullner, K.; Papaefthymiou, G.; Bergthaler, P.; Smolle, J. Safety and efficacy of interferon alfa-2b in the adjuvant treatment of uveal melanoma. Ophthalmologe 2006, 103, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, P.A.; Butt, M.; Eswar, C.V.; Gillis, P.; Marshall, E. A prospective single arm phase II study of dacarbazine and treosulfan as first-line therapy in metastatic uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2006, 16, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmittel, A.; Schuster, R.; Bechrakis, N.E.; Siehl, J.M.; Foerster, M.H.; Thiel, E.; Keilholz, U. A two-cohort phase II clinical trial of gemcitabine plus treosulfan in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2005, 15, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrie, P.G.; Shaw, J.; Spanswick, V.J.; Sehmbi, R.; Jonson, A.; Mayer, A.; Bulusu, R.; Hartley, J.A.; Cree, I.A. Phase I trial combining gemcitabine and treosulfan in advanced cutaneous and uveal melanoma patients. Br. J. Cancer 2005, 92, 1997–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schmittel, A.; Scheulen, M.E.; Bechrakis, N.E.; Strumberg, D.; Baumgart, J.; Bornfeld, N.; Foerster, M.H.; Thiel, E.; Keilholz, U. Phase II trial of cisplatin, gemcitabine and treosulfan in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2005, 15, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt-Hieber, M.; Schmittel, A.; Thiel, E.; Keilholz, U. A phase II study of bendamustine chemotherapy as second-line treatment in metastatic uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2004, 14, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keilholz, U.; Schuster, R.; Schmittel, A.; Bechrakis, N.; Siehl, J.; Foerster, M.H.; Thiel, E. A clinical phase I trial of gemcitabine and treosulfan in uveal melanoma and other solid tumours. Eur. J. Cancer 2004, 40, 2047–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terheyden, P.; Brocker, E.B.; Becker, J.C. Clinical evaluation of in vitro chemosensitivity testing: The example of uveal melanoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 130, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfohler, C.; Cree, I.A.; Ugurel, S.; Kuwert, C.; Haass, N.; Neuber, K.; Hengge, U.; Corrie, P.G.; Zutt, M.; Tilgen, W.; et al. Treosulfan and gemcitabine in metastatic uveal melanoma patients: Results of a multicenter feasibility study. Anticancer Drugs 2003, 14, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedikian, A.Y.; Papadopoulos, N.; Plager, C.; Eton, O.; Ring, S. Phase II evaluation of temozolomide in metastatic choroidal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2003, 13, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivela, T.; Suciu, S.; Hansson, J.; Kruit, W.H.; Vuoristo, M.S.; Kloke, O.; Gore, M.; Hahka-Kemppinen, M.; Parvinen, L.M.; Kumpulainen, E.; et al. Bleomycin, vincristine, lomustine and dacarbazine (BOLD) in combination with recombinant interferon alpha-2b for metastatic uveal melanoma. Eur. J. Cancer 2003, 39, 1115–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyrhonen, S.; Hahka-Kemppinen, M.; Muhonen, T.; Nikkanen, V.; Eskelin, S.; Summanen, P.; Tarkkanen, A.; Kivela, T. Chemoimmunotherapy with bleomycin, vincristine, lomustine, dacarbazine (BOLD), and human leukocyte interferon for metastatic uveal melanoma. Cancer 2002, 95, 2366–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.C.; Terheyden, P.; Kampgen, E.; Wagner, S.; Neumann, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Steinmann, A.; Wittenberg, G.; Lieb, W.; Brocker, E.B. Treatment of disseminated ocular melanoma with sequential fotemustine, interferon alpha, and interleukin 2. Br. J. Cancer 2002, 87, 840–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerhorst, J.A.; Bedikian, A.Y.; Smith, T.M.; Papadopoulos, N.E.; Plager, C.; Eton, O. Phase II trial of 9-nitrocamptothecin (RFS 2000) for patients with metastatic cutaneous or uveal melanoma. Anticancer Drugs 2002, 13, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, W.C.; Lohmann, R.C. Oral indomethacin and ranitidine in advanced melanoma: A phase II study. Clin. Oncol. (R. Coll. Radiol.) 1996, 8, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penel, N.; Delcambre, C.; Durando, X.; Clisant, S.; Hebbar, M.; Negrier, S.; Fournier, C.; Isambert, N.; Mascarelli, F.; Mouriaux, F. O-Mel-Inib: A Cancero-pole Nord-Ouest multicenter phase II trial of high-dose imatinib mesylate in metastatic uveal melanoma. Investig. New Drugs 2008, 26, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompella, U.B.; Amrite, A.C.; Pacha Ravi, R.; Durazo, S.A. Nanomedicines for back of the eye drug delivery, gene delivery, and imaging. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2013, 36, 172–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- You, S.; Luo, J.; Grossniklaus, H.E.; Gou, M.L.; Meng, K.; Zhang, Q. Nanomedicine in the application of uveal melanoma. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 9, 1215–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, K.; Misra, M. A review on recent drug delivery systems for posterior segment of eye. Biomed. Pharm. 2018, 107, 1564–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, B.; Bucolo, C.; Giannavola, C.; Puglisi, G.; Giunchedi, P.; Conte, U. Biodegradable microspheres for the intravitreal administration of acyclovir: In vitro/in vivo evaluation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 1997, 5, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompella, U.B.; Kadam, R.S.; Lee, V.H. Recent advances in ophthalmic drug delivery. Ther. Deliv. 2010, 1, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rowe-Rendleman, C.L.; Durazo, S.A.; Kompella, U.B.; Rittenhouse, K.D.; Di Polo, A.; Weiner, A.L.; Grossniklaus, H.E.; Naash, M.I.; Lewin, A.S.; Horsager, A.; et al. Drug and gene delivery to the back of the eye: From bench to bedside. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 2714–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beiu, C.; Giurcaneanu, C.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Holban, A.M.; Popa, L.G.; Mihai, M.M. Nanosystems for Improved Targeted Therapies in Melanoma. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fallico, M.; Maugeri, A.; Romano, G.L.; Bucolo, C.; Longo, A.; Bonfiglio, V.; Russo, A.; Avitabile, T.; Barchitta, M.; Agodi, A.; et al. Epiretinal Membrane Vitrectomy With and Without Intraoperative Intravitreal Dexamethasone Implant: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 635101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triozzi, P.L.; Singh, A.D. Adjuvant Therapy of Uveal Melanoma: Current Status. Ocul. Oncol. Pathol. 2014, 1, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, A.D.; Bergman, L.; Seregard, S. Uveal melanoma: Epidemiologic aspects. Ophthalmol. Clin. N. Am. 2005, 18, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krantz, B.A.; Dave, N.; Komatsubara, K.M.; Marr, B.P.; Carvajal, R.D. Uveal melanoma: Epidemiology, etiology, and treatment of primary disease. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2017, 11, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Damato, B.; Duke, C.; Coupland, S.E.; Hiscott, P.; Smith, P.A.; Campbell, I.; Douglas, A.; Howard, P. Cytogenetics of uveal melanoma: A 7-year clinical experience. Ophthalmology 2007, 114, 1925–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eleuteri, A.; Taktak, A.F.G.; Coupland, S.E.; Heimann, H.; Kalirai, H.; Damato, B. Prognostication of metastatic death in uveal melanoma patients: A Markov multi-state model. Comput. Biol. Med. 2018, 102, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo, D.; Piulats, J.M.; Ochoa, M.; Arias, L.; Gutierrez, C.; Catala, J.; Cobos, E.; Garcia-Bru, P.; Dias, B.; Padron-Perez, N.; et al. Clinical predictors of survival in metastatic uveal melanoma. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 63, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto, E.B.; Zielinska, A.; Luis, M.; Carbone, C.; Martins-Gomes, C.; Souto, S.B.; Silva, A.M. Uveal melanoma: Physiopathology and new in situ-specific therapies. Cancer Chemother. Pharm. 2019, 84, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- NCCN. N.C.C.N. Uveal Melanoma. Version 2. 2021. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1488 (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Seth, R.; Messersmith, H.; Kaur, V.; Kirkwood, J.M.; Kudchadkar, R.; McQuade, J.L.; Provenzano, A.; Swami, U.; Weber, J.; Alluri, K.C.; et al. Systemic Therapy for Melanoma: ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3947–3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Manson, D.K.; Marr, B.P.; Carvajal, R.D. Treatment of uveal melanoma: Where are we now? Adv. Med. Oncol. 2018, 10, 1758834018757175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, F.; Caltabiano, G.; Queirolo, P. Uveal melanoma. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2012, 38, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, F.; Grosso, M.; Picasso, V.; Tornari, E.; Pesce, M.; Queirolo, P. Treatment of metastatic uveal melanoma with intravenous fotemustine. Melanoma Res. 2013, 23, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, B.; Hampson, G.; Michaels, J.; Towse, A.; von der Schulenburg, J.G.; Wong, O. Advanced therapy medicinal products and health technology assessment principles and practices for value-based and sustainable healthcare. Eur. J. Health Econ. HEPAC Health Econ. Prev. Care 2019, 20, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Helgadottir, H.; Hoiom, V. The genetics of uveal melanoma: Current insights. Appl. Clin. Genet. 2016, 9, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Javed, A.; Arguello, D.; Johnston, C.; Gatalica, Z.; Terai, M.; Weight, R.M.; Orloff, M.; Mastrangelo, M.J.; Sato, T. PD-L1 expression in tumor metastasis is different between uveal melanoma and cutaneous melanoma. Immunotherapy 2017, 9, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maio, M.; Danielli, R.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Pigozzo, J.; Parmiani, G.; Ridolfi, R.; De Rosa, F.; Del Vecchio, M.; Di Guardo, L.; Queirolo, P.; et al. Efficacy and safety of ipilimumab in patients with pre-treated, uveal melanoma. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 2911–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelderman, S.; van der Kooij, M.K.; van den Eertwegh, A.J.; Soetekouw, P.M.; Jansen, R.L.; van den Brom, R.R.; Hospers, G.A.; Haanen, J.B.; Kapiteijn, E.; Blank, C.U. Ipilimumab in pretreated metastastic uveal melanoma patients. Results of the Dutch Working group on Immunotherapy of Oncology (WIN-O). Acta Oncol. 2013, 52, 1786–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luke, J.J.; Callahan, M.K.; Postow, M.A.; Romano, E.; Ramaiya, N.; Bluth, M.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Lawrence, D.P.; Ibrahim, N.; Ott, P.A.; et al. Clinical activity of ipilimumab for metastatic uveal melanoma: A retrospective review of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, and University Hospital of Lausanne experience. Cancer 2013, 119, 3687–3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piulats Rodriguez, J.M.; Ochoa de Olza, M.; Codes, M.; Lopez-Martin, J.A.; Berrocal, A.; García, M.; Gurpide, A.; Homet, B.; Martin-Algarra, S. Phase II study evaluating ipilimumab as a single agent in the first-line treatment of adult patients (Pts) with metastatic uveal melanoma (MUM): The GEM-1 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 9033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Grob, J.J.; Rutkowski, P.; Lao, C.D.; Cowey, C.L.; Schadendorf, D.; Wagstaff, J.; Dummer, R.; et al. Five-Year Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1535–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Algazi, A.P.; Tsai, K.K.; Shoushtari, A.N.; Munhoz, R.R.; Eroglu, Z.; Piulats, J.M.; Ott, P.A.; Johnson, D.B.; Hwang, J.; Daud, A.I.; et al. Clinical outcomes in metastatic uveal melanoma treated with PD-1 and PD-L1 antibodies. Cancer 2016, 122, 3344–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelster, M.S.; Gruschkus, S.K.; Bassett, R.; Gombos, D.S.; Shephard, M.; Posada, L.; Glover, M.S.; Simien, R.; Diab, A.; Hwu, P.; et al. Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Metastatic Uveal Melanoma: Results From a Single-Arm Phase II Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damato, B.E.; Dukes, J.; Goodall, H.; Carvajal, R.D. Tebentafusp: T Cell Redirection for the Treatment of Metastatic Uveal Melanoma. Cancers 2019, 11, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- ESMO. Promising Results are Provided by Tebentafusp in Metastatic Uveal Melanoma. Available online: https://www.esmo.org/oncology-news/promising-results-are-provided-by-tebentafusp-in-metastatic-uveal-melanoma (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Sacco, J.J.; Carvajal, R.; Butler, M.O.; Shoushtari, A.N.; Hassel, J.C.; Ikeguchi, A.; Hernandez-Aya, L.; Nathan, P.; Hamid, O.; Piulats Rodriguez, J.M.; et al. A Phase (ph) II, Multi-Center Study of the Safety and Efficacy of Tebentafusp (Tebe) (IMCgp100) in Patients (pts) with Metastatic Uveal Melanoma (mUM). Available online: https://oncologypro.esmo.org/meeting-resources/esmo-immuno-oncology-virtual-congress-2020/a-phase-ph-ii-multi-center-study-of-the-safety-and-efficacy-of-tebentafusp-tebe-imcgp100-in-patients-pts-with-metastatic-uveal-melanoma-mum (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Immunocore. Novel Immunotherapy Tebentafusp Granted Fast Track Designation for Metastatic Uveal Melanoma. Available online: https://www.targetedonc.com/view/novel-immunotherapy-tebentafusp-granted-fast-track-designation-for-metastatic-uveal-melanoma (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Immunocore. Immunocore’s IMCgp100 Receives Promising Innovative Medicine (PIM) Designation under UK Early Access to Medicines Scheme (EAMS) for the Treatment of Patients with Uveal Melanoma. 11 December 2017. Available online: https://bit.ly/2UUPKNU (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Vivet-Noguer, R.; Tarin, M.; Roman-Roman, S.; Alsafadi, S. Emerging Therapeutic Opportunities Based on Current Knowledge of Uveal Melanoma Biology. Cancers 2019, 11, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Russo, A.; Ragusa, M.; Barbagallo, C.; Longo, A.; Avitabile, T.; Uva, M.G.; Bonfiglio, V.; Toro, M.D.; Caltabiano, R.; Mariotti, C.; et al. miRNAs in the vitreous humor of patients affected by idiopathic epiretinal membrane and macular hole. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, M.D.; Reibaldi, M.; Avitabile, T.; Bucolo, C.; Salomone, S.; Rejdak, R.; Nowomiejska, K.; Tripodi, S.; Posarelli, C.; Ragusa, M.; et al. MicroRNAs in the Vitreous Humor of Patients with Retinal Detachment and a Different Grading of Proliferative Vitreoretinopathy: A Pilot Study. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).