Abstract

Background/Objectives: Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have generated a revolutionary approach in the treatment of cancer, but their effectiveness has been compromised by immune-related adverse events, including renal damage. Although rare, these effects are relevant because they have been related to poor patient prognoses. The objective of this review was to estimate the current incidence of nephrotoxicity in patients treated with single and double ICI therapies. Methods: A total of 1283 potential articles were identified, which were reduced to 50 after applying the exclusion and inclusion criteria. Results: This study reveals the increase in acute kidney injury associated with these drugs in the last decade and shows that, interestingly, combined therapies with ICIs does not lead to an increase in kidney damage compared with anti-CTLA-4. It also suggests that kidney damage could be underdiagnosed when it comes to interstitial nephritis, because definitive evidence requires a renal biopsy. Conclusions: In perspective, these conclusions could guide clinicians in making decisions for therapy personalization and highlight the need to search for new diagnostic systems that are more sensitive and specific to the type of damage and could replace the biopsy.

1. Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are monoclonal antibodies specifically directed at blocking immune checkpoints (molecules that regulate the balance between the elimination of foreign antigens and the recognition of autoantigens). These are IgG1-, IgG2-, and IgG4-type human or humanized immunoglobulins. Their pharmacological activity lies in blocking the inhibitory receptors found on T cells, thus allowing their activation and increasing the immune response. Consequently, ICIs reestablish the action of T cells against tumors [1,2].

ICIs have changed the treatment paradigm for several types of tumors with poor prognoses in the last decade. There are three ICI families available for clinical use. On the one hand are those that block immune checkpoints or inhibitory T-cell receptors, i.e., antibodies binding to and blocking the cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), representing the anti-CTLA-4 family, and those that prevent the binding of activating ligands to the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), constituting the anti-PD-1 family. On the other hand, there is another family of antibodies that bind to and block the ligands found on tumor cells (PD-L1), which bind and activate PD-1 receptors in lymphocytes. These form the anti-PD-L1 antibody family [1,2].

In 2011, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first ICI with a therapeutic indication to treat metastatic melanoma cancer. This anti-CTLA-4 antibody, named ipilimumab, was the pioneer preceding eight currently authorized antibodies: tremelimumab (anti-CTLA-4); nivolumab, pembrolizumab, cemiplimab, and dostarlimab (anti-PD-1); and avelumab, durvalumab, and atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1) [3,4].

The clinical use of these nine FDA-approved ICIs has expanded over more than nineteen different therapeutic indications [5]. Furthermore, combined ICI therapy poses a breakthrough in the treatment of some types of cancer, such as non-small-cell lung cancer and metastatic melanoma, in which the concomitant administration of ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) and nivolumab (anti-PD-1) increases the response rate and survival [6].

However, despite their innovative nature and the improvement in efficacy and safety, the use of these drugs has also unveiled a number of adverse events related to the immune system resulting from the boost in the immune response [7]. The incidence of adverse effects appears to be higher in patients receiving combined therapy compared with those receiving monotherapies, which would limit their use [8].

Kidney injury is one of the complications observed. Although not the commonest, renal toxicity is a relevant complication associated with a poorer prognosis [5]. Acute kidney injury (AKI), proteinuria, and electrolyte disorders are the main pathologies of the renal system associated with ICI treatment [9], and the most common pathological lesion that leads to AKI is tubulointerstitial nephritis (90% of cases) [10]. There are also other lesions associated with the autoreactivity of the immune system, such as glomerulonephritis [11].

Since the introduction of these drugs in 2011, the incidence of undesired renal effects has grown due to the increasing use and abundance of authorized ICIs and improved diagnosis [12]. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses dealing with the incidence of renal damage in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors have been previously published, such as those by Liu et al. 2023 [13] and Xie et al. 2023 [14]. However, due to the limited experience accumulated since the recent introduction of these drugs, updated knowledge on incidence, based on the progressively increasing data available, may help guide decision making and optimize treatment. On these grounds, we aimed to estimate the current incidence of nephrotoxicity in cancer patients treated with single and double ICI therapies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Retrieval of Published Studies

A bibliographic search of clinical studies published in Medline and the Web of Science databases until 4 September 2024 was carried out by entering the following keyword combinations: “(nephrotoxicity OR renal toxicity OR renal damage OR renal injury OR kidney injury OR kidney damage) AND (immune checkpoint inhibitor OR ICI OR ICPI OR ipilimumab OR tremelimumab OR nivolumab OR pembrolizumab OR cemiplimab OR atezolizumab OR durvalumab OR avelumab OR PD-1 OR CTLA-4 OR PD-L1)”. The filters used were: “Humans”, “English”.

2.2. Exclusion and Inclusion Criteria

Study selection was carried out following the PRISMA guidelines. Two researchers (J.T. and L.V.-V.) independently withdrew those articles that met any of the following exclusion criteria: (1) preclinical studies, (2) reviews, protocols, communications, and letters to the editor, (3) written in a language other than English, (4) full text not available, and (5) studies evaluating the renal safety of combined therapies of ICIs with other antineoplastic drugs. After that, they selected those studies that met all of the following inclusion criteria: (1) clinical studies evaluating at least one ICI drug and (2) evaluating at least one kidney damage parameter: AKI or nephritis (independently for each ICI family). Discrepancies in article selection were resolved by a third researcher (A.G.C.). The screening was carried out with the online tool “Systematic review facility” [15].

This protocol was registered with the International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (INPLASY registration number: INPLASY202510053) [16].

2.3. Data Extraction

The following data were extracted from each included work: first author’s name, publication year, study design and duration, geographic location, number of patients included, patient characteristics, tumor type and stage, ICI drugs, posology, route of administration, duration of treatment, Jadad or MINORS scale, and number of patients who presented alterations in any of the following parameters of kidney damage: AKI (elevation of plasma creatinine or renal failure) and nephritis. Study quality was assessed with the Jadad scale [17] (for prospective randomized studies) or the MINORS scale [18] (for retrospective or prospective, non-randomized studies). A threshold score of 2 out of 5 (in the Jadad scale) or 7 out of 16 (in the MINORS scale) was established for inclusion in this review.

2.4. Calculation of Incidence

In each clinical study, percentage incidence of AKI and nephritis were calculated according to the following formula:

The weighted mean and the standard error of the mean of AKI and nephritis incidence in ICI families and in the anti-PD-1 + anti-CTLA-4 combination were also calculated. In addition, the weighted mean and the standard error of the mean of the incidence of the kidney damage parameters of nivolumab (anti-PD-1), pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1), atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1), durvalumab (anti-PD-L1), ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4), tremelimumab (anti-CTLA-4), nivolumab + ipilimumab (anti-PD-1 + anti-CTLA-4), and pembrolizumab + ipilimumab (anti-PD-1 + anti-CTLA-4) were also calculated. Figures design was carried out with Microsoft Office 365® software (Redmond, WA, USA).

3. Results

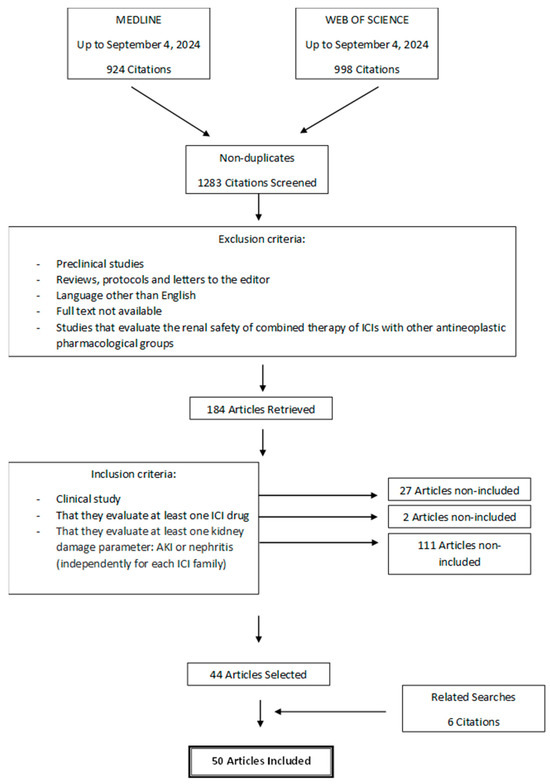

The flow chart describing the study search process and definitive inclusion of cited references is presented in Figure 1. A total of 1283 potential articles were identified, which, after applying the exclusion and inclusion criteria, was reduced to 44 selected articles. During the data extraction stage of the studies, 6 new articles were included from related searches, adding up to a total of 50 clinical studies. The descriptive data of the 50 clinical studies finally included in the review are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of search and selection of studies carried out in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review. Acute kidney injury (AKI).

The 50 clinical studies analyzed in this review were mostly retrospective studies and a few prospective and randomized clinical trials carried out in different hospitals worldwide, mostly with metastatic melanoma and metastatic renal cancer patients, but also with patients with other types of cancer such as non-small-cell lung cancer. The most commonly used ICIs were nivolumab and pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1), ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4), and the combined therapy of nivolumab + ipilimumab. These drugs were administered intravenously for several cycles, essentially every 2 or 3 weeks. The most frequently quantified parameter to evaluate renal function was the elevation of plasma creatinine.

The incidence of AKI was practically similar in the groups of anti-PD-1 (5.32%) and anti-PD-L1 (5.25%) but increased in patients treated with anti-CTLA-4 drugs (7.83%). Yet, it is noteworthy that ipilimumab had a higher incidence of AKI than tremelimumab (7.87% versus 4.35%, respectively). The higher incidence of AKI observed with ipilimumab may be related to the longer period of time that this drug has been used in clinical practice and the greater number of observational studies available (ipilimumab was the first ICI approved by the FDA in 2011, in contrast to tremelimumab, which was approved in 2022) [4]. On the other hand, the incidence of AKI in the combined therapy group (anti-PD-1 + anti-CTLA-4) was 5.58% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Incidences of acute kidney injury (AKI) and nephritis in patients treated with ICIs in monotherapy and in combination. SEM, standard error of the mean.

The mean incidence of nephritis in patients treated with anti-PD-1 did not exceed 1.5% (Table 2). However, the clinical study carried out by O’Reilly et al. in 2019 reported an incidence of nephritis of 3.39% in patients treated with ipilimumab [45]. In relation to the combined drug therapy (anti-PD-1 + anti-CTLA-4), the mean incidence of nephritis reached values around 2%, although the study carried out by Tykody et al. in 2022 evidenced an incidence of nephritis in patients treated with nivolumab + ipilimumab of 3.85% [62].

4. Discussion

ICIs have revolutionized the treatment of certain types of tumors, but their effectiveness has been limited by adverse effects related to the immune system, including renal effects [9,68]. Furthermore, numerous clinical studies have validated their advantageous efficacy profile not only when administered as monotherapy or in combination, but also when combined with chemotherapy, which has led to an increase in the survival of cancer patients [69].

Our study reveals that the incidence of AKI has kept growing in recent years (anti-PD-1 ~5%, anti-PD-L1 ~5%, anti-CTLA-4 ~8%, anti-PD-1 + anti-CTLA-4 ~6%), leaving outdated the previous incidence values of 2–3% for monotherapies and 5% for combined therapies [70]. The actual incidence of nephrotoxicity might be even higher, and damage is likely underdiagnosed in subclinical, asymptomatic, and mild cases due to the poor and sub-optimally sensitive diagnosis technology. In fact, current diagnosis of AKI is curtailed by the known limitations in sensitivity and specificity of the standard biomarker, plasma creatinine [71].

According to the existing literature, nephritis is the cause of 90% of ICI nephrotoxicity cases [10]. However, in this study we did not find incidences of nephritis that were too high (between 1 and 3%) for what would be expected taking into account that nephritis is the main cause of nephrotoxicity. This suggests that nephritis could be underestimated in many studies because definitive diagnosis is made by biopsy [70], which is medically restricted because of its invasive nature and potential complications [72].

ICIs’ toxicity is related to their pharmacological action, namely the release of the physiological blockages that regulate the immune response [9,68]. However, the anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 families act differently because they differ in the location of their molecular targets, the stage of T-cell activation they facilitate, and the signaling pathways involved [73]. This could be the reason why the anti-PD-1 family is more effective and less toxic than the anti-CTLA-4 family, a fact that has been observed in various types of cancer, such as advanced melanoma [74,75,76]. This systematic review agrees with previous studies that show a higher incidence of adverse effects (also AKI) in patients treated with anti-CTLA-4 drugs compared with those treated with anti-PD-1.

The joint administration of anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 could provide synergistic efficacy due to the combination of their different mechanisms of action, which could justify a higher response rate and survival of patients. However, this increase in efficacy could also entail an upsurge in adverse effects [6] that limit their use. With regard to nephrotoxicity, our study contrasts with the existing literature [6,77]. The incidence of AKI following the single anti-CTLA-4 treatment is 7.83%, while after combined therapy of anti-PD-1 + anti-CTLA-4, it is not greater (5.58%). These data suggest that the combined therapy would provide a benefit from an improved antitumor efficacy with no additional nephrotoxic burden.

The findings highlighted in this review updating the kidney damage incidence data reveal the favorable benefit–risk balance of combined ICI therapies in order to improve clinical decision making [23,24,35,63]. In many cases, this could be a successful therapeutic strategy, which would allow two families of ICIs to be included in the therapy without increasing the risk of suffering adverse renal effects (the incidence of kidney damage is not greater than after a single anti-CTLA-4). This is an important piece of information for clinical decision making, since recent systematic reviews, such as that by Xie et al., 2023 [14], report higher incidences of renal damage for combined ICI therapy than for monotherapies.

The different toxicities of these drug families could be related to the mechanism of action of each of them. The blockade carried out by anti-CTLA-4 on the CTLA-4 receptor at the lymph node level alters the quiescence phase of T cells and promotes their activation. This blockade of the inhibitory receptor restores the activating signal of the CD28 costimulatory receptor. Consequently, T cells are activated, and the adaptive immune response against tumor cells is regenerated [9,78]. However, PD-1/PD-L1 blockade occurs at a different site than CTLA-4 blockade. It affects the effector phase of the adaptive immune response and takes place in the tumor microenvironment [68]. In this sense, the T cell–CD28 costimulatory receptor signaling pathway is reestablished. As a result, the production of cytokines, the proliferation of T lymphocytes, and the cytotoxic activity of the T cell is promoted [9,73,78]. This would translate, in addition to the therapeutic response, into the appearance of adverse effects, including kidney effects, due to the attack of autoantigens as a consequence of the overactivation of the lymphocyte system.

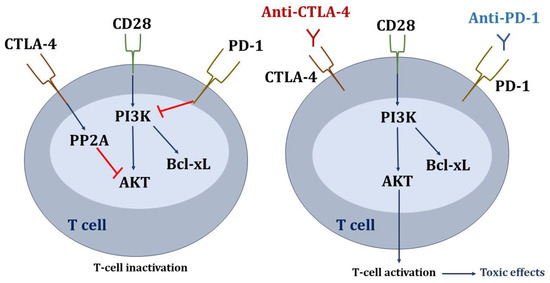

Regarding the signaling pathways affected in T lymphocytes (Figure 2), the inhibitory signals through PD-1 and CTLA-4 converge on serine-threonine kinase (AKT), although the inhibition pathways are different. Parry RV et al. demonstrated that PD-1 signaling blocks CD28-mediated activation of inositolphosphatidyl-3-kinase (PI3K) and AKT. Inhibitory CTLA-4 signaling preserves PI3K activity but inhibits AKT directly through the activation of the phosphatase protein PP2A. Therefore, anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 antibodies would act at different levels in the T-cell signaling cascade in order to stimulate immune activation [78].

Figure 2.

Signaling pathways affected in T lymphocytes due to the inhibition of check points. Blue arrows mean activation, and red lines mean inhibition.

Recently, anti-CTLA-4 drugs have been called “immune enhancers”, and anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 drugs “immune normalizers” [79]. In this sense, anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 would cause a normalization of immunity, while anti-CTLA-4 would enhance it. This fact could justify the greater renal toxicity produced by anti-CTLA-4 drugs with respect to anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1.

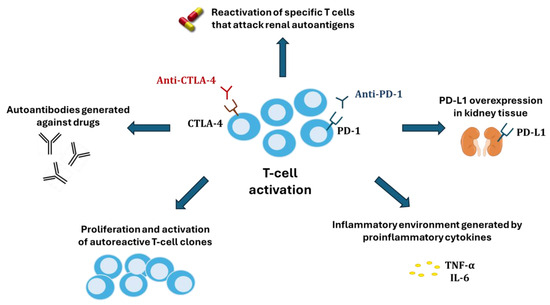

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the nephrotoxicity of ICIs (Figure 3). One of these is the reactivation of specific T cells (in the latency period) that had been generated after the administration of other nephrotoxic drugs (proton pump inhibitors, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and antibiotics) [80] and which could now attack renal autoantigens. Alternatively, ICIs could cause an abnormal proliferation and activation of autoreactive T-cell clones or the production of autoantibodies by B cells recognizing self-antigens in tubular epithelial cells, mesangial cells, or podocytes, until then tolerated by the immune system [9]. A third potential mechanism would be the inflammatory environment generated within kidney tissue by proinflammatory cytokines secreted by T cells. Finally, because renal tubular cells constitutively express PD-L1 to avoid T cell-mediated autoimmunity, blocking its interaction with PD-1 in T cells could disable the defense and facilitate cytotoxic injury [81].

Figure 3.

Mechanisms of kidney damage associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Our study has encountered a few caveats that limit coherent comparison among the studies, which need to be addressed in future studies reporting ICI nephrotoxicity. For instance, the absence of a standard definition and diagnostic criteria for ICI nephropathy prevents the full leverage and integration of data from multiple studies. An international consensus initiative is necessary in this regard.

In conclusion, this review reveals an increased incidence of AKI associated with ICI drugs that should alert clinicians, especially in patients at risk. On the other hand, it also shows that combined ICI therapy is not more nephrotoxic than single anti-CTLA-4 therapy, underpinning a better efficacy-to-safety relation than previously reported. Finally, it suggests that kidney damage could be underdiagnosed because of the absence of reliable, non-invasive technology for differential diagnosis, as conclusive diagnosis still requires a biopsy.

There is a need to search for new, earlier, and more sensitive diagnostic systems. In this sense, new, preferably urinary, biomarkers or, more probably, collections of biomarkers are sought to compose etiological fingerprints with which to differentiate underlying damage patterns through a liquid biopsy. In addition, longer term follow-up studies should be conducted to monitor the evolution and duration of renal side effects and the sequelae of single and double therapies with traditional and new diagnostic methods under a unified definition of ICI nephropathy that allows for cross-study data standardization and comparison.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.I.M.; methodology, J.T., A.G.C. and L.V.-V.; investigation, J.T.; data curation, A.I.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.T.; writing—review and editing, A.I.M., A.G.C., L.V.-V. and F.J.L.-H.; supervision, A.I.M. and F.J.L.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) through the project “PI20/01351”, co-funded by the European Union; and RICORS2040 (Kidney Disease) of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (RD21/0005/0004 and RD24/0004/0024), co-funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU, Mecanismo para la Recuperación y la Resiliencia (MRR). Javier Tascón is a recipient of a predoctoral fellowship from the University of Salamanca, co-funded by Banco Santander.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviation

| AKI | Acute kidney injury |

| AKT | Serine-threonine kinase |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 |

| FDA | United States Food and Drug Administration |

| ICIs | Immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| IgG1 | G1 immunoglobulin |

| IgG2 | G2 immunoglobulin |

| IgG4 | G4 immunoglobulin |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PD-L1 | Ligand 1 of programmed cell death protein |

| PI3K | Inositolphosphatidyl-3-kinase |

| PP2A | Phosphatase protein 2A |

References

- Seidel, J.A.; Otsuka, A.; Kabashima, K. Anti-PD-1 and Anti-CTLA-4 Therapies in Cancer: Mechanisms of Action, Efficacy, and Limitations. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perazella, M.A.; Shirali, A.C. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Nephrotoxicity: What Do We Know and What Should We Do? Kidney Int. 2020, 97, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twomey, J.D.; Zhang, B. Cancer Immunotherapy Update: FDA-Approved Checkpoint Inhibitors and Companion Diagnostics. AAPS J. 2021, 23, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. FDA Approves Tremelimumab in Combination with Durvalumab and Platinum-Based Chemotherapy for Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-tremelimumab-combination-durvalumab-and-platinum-based-chemotherapy-metastatic-non (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Seethapathy, H.; Herrmann, S.M.; Sise, M.E. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Kidney Toxicity: Advances in Diagnosis and Management. Kidney Med. 2021, 3, 1074–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Grob, J.J.; Cowey, C.L.; Lao, C.D.; Schadendorf, D.; Dummer, R.; Smylie, M.; Rutkowski, P.; et al. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab or Monotherapy in Previously Untreated Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barquín-García, A.; Molina-Cerrillo, J.; Garrido, P.; Garcia-Palos, D.; Carrato, A.; Alonso-Gordoa, T. New Oncologic Emergencies: What Is There to Know about Inmunotherapy and Its Potential Side Effects? Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 66, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, M.; Jiang, T.; Ren, S.; Zhou, C. Combination Strategies on the Basis of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Where Do We Stand? Clin. Lung Cancer 2018, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzin, R.; Netti, G.S.; Spadaccino, F.; Porta, C.; Gesualdo, L.; Stallone, G.; Castellano, G.; Ranieri, E. The Use of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Oncology and the Occurrence of AKI: Where Do We Stand? Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 574271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortazar, F.B.; Marrone, K.A.; Troxell, M.L.; Ralto, K.M.; Hoenig, M.P.; Brahmer, J.R.; Le, D.T.; Lipson, E.J.; Glezerman, I.G.; Wolchok, J.; et al. Clinicopathological Features of Acute Kidney Injury Associated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Kidney Int. 2016, 90, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortazar, F.B.; Kibbelaar, Z.A.; Glezerman, I.G.; Abudayyeh, A.; Mamlouk, O.; Motwani, S.S.; Murakami, N.; Herrmann, S.M.; Manohar, S.; Shirali, A.C.; et al. Clinical Features and Outcomes of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor–Associated AKI: A Multicenter Study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 31, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isik, B.; Alexander, M.P.; Manohar, S.; Vaughan, L.; Kottschade, L.; Markovic, S.; Lieske, J.; Kukla, A.; Leung, N.; Herrmann, S.M. Biomarkers, Clinical Features, and Rechallenge for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Renal Immune-Related Adverse Events. Kidney Int. Rep. 2021, 6, 1022–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wei, W.; Yang, L.; Li, J.; Yi, C.; Pu, Y.; Yin, T.; Na, F.; Zhang, L.; Fu, P.; et al. Incidence and Risk Factors of Acute Kidney Injury in Cancer Patients Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1173952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, W.; Xiao, S.; Li, X.; Huang, J.; Li, G.; Zhang, Z. Incidence, Mortality, and Risk Factors of Acute Kidney Injury after Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Real-World Evidence. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 115, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahor, Z.; Liao, J.; Currie, G.; Ayder, C.; Macleod, M.; McCann, S.K.; Bannach-Brown, A.; Wever, K.; Soliman, N.; Wang, Q.; et al. Development and Uptake of an Online Systematic Review Platform: The Early Years of the CAMARADES Systematic Review Facility (SyRF). BMJ Open Sci. 2021, 5, e100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tascón, A.; Casanova, A.G.; Vicente-Vicente, L.; López-Hernández, F.J.; Morales, A.I. Nephrotoxicity of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Single and Combination Therapy. A Systematic and Critical Review INPLASY Protocol 202510053. Available online: https://inplasy.com/inplasy-2025-1-0053/ (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Jadad, A.R.; Moore, R.A.; Carroll, D.; Jenkinson, C.; Reynolds, D.J.; Gavaghan, D.J.; McQuay, H.J. Assessing the Quality of Reports of Randomized Clinical Trials: Is Blinding Necessary? Control. Clin. Trials 1996, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slim, K.; Nini, E.; Forestier, D.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Panis, Y.; Chipponi, J. Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS): Development and Validation of a New Instrument. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahim, M.; Mamlouk, O.; Lin, H.; Lin, J.; Page, V.; Abdel-Wahab, N.; Swan, J.; Selamet, U.; Yee, C.; Diab, A.; et al. Incidence, Predictors, and Survival Impact of Acute Kidney Injury in Patients with Melanoma Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A 10-Year Single-Institution Analysis. Oncoimmunology 2021, 10, 1927313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonia, S.J.; López-Martin, J.A.; Bendell, J.; Ott, P.A.; Taylor, M.; Eder, J.P.; Jäger, D.; Pietanza, M.C.; Le, D.T.; de Braud, F.; et al. Nivolumab Alone and Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Recurrent Small-Cell Lung Cancer (CheckMate 032): A Multicentre, Open-Label, Phase 1/2 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apolo, A.B.; Ellerton, J.A.; Infante, J.R.; Agrawal, M.; Gordon, M.S.; Aljumaily, R.; Gourdin, T.; Dirix, L.; Lee, K.-W.; Taylor, M.H.; et al. Avelumab as Second-Line Therapy for Metastatic, Platinum-Treated Urothelial Carcinoma in the Phase Ib JAVELIN Solid Tumor Study: 2-Year Updated Efficacy and Safety Analysis. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e001246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, M.B.; Hodi, F.S.; Thompson, J.A.; McDermott, D.F.; Hwu, W.-J.; Lawrence, D.P.; Dawson, N.A.; Wong, D.J.; Bhatia, S.; James, M.; et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Pegylated Interferon Alfa-2b or Ipilimumab for Advanced Melanoma or Renal Cell Carcinoma: Dose-Finding Results from the Phase Ib KEYNOTE-029 Study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 1805–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkins, M.B.; Jegede, O.A.; Haas, N.B.; McDermott, D.F.; Bilen, M.A.; Stein, M.; Sosman, J.A.; Alter, R.; Plimack, E.R.; Ornstein, M.C.; et al. Phase II Study of Nivolumab and Salvage Nivolumab/Ipilimumab in Treatment-Naïve Patients with Advanced Non-Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (HCRN GU16-260-Cohort B). J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e004780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blas, L.; Shiota, M.; Tsukahara, S.; Nagakawa, S.; Matsumoto, T.; Eto, M. Adverse Events of Cabozantinib Plus Nivolumab Versus Ipilimumab Plus Nivolumab. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2024, 22, e122–e127.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, M.T.; Matin, S.F.; Tam, A.L.; Sheth, R.A.; Ahrar, K.; Tidwell, R.S.; Rao, P.; Karam, J.A.; Wood, C.G.; Tannir, N.M.; et al. Pilot Study of Tremelimumab with and without Cryoablation in Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizman, N.; Meza, L.; Bergerot, P.; Alcantara, M.; Dorff, T.; Lyou, Y.; Frankel, P.; Cui, Y.; Mira, V.; Llamas, M.; et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab with or without Live Bacterial Supplementation in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Randomized Phase 1 Trial. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espi, M.; Teuma, C.; Novel-Catin, E.; Maillet, D.; Souquet, P.J.; Dalle, S.; Koppe, L.; Fouque, D. Renal Adverse Effects of Immune Checkpoints Inhibitors in Clinical Practice: ImmuNoTox Study. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 147, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flippot, R.; Dalban, C.; Laguerre, B.; Borchiellini, D.; Gravis, G.; Négrier, S.; Chevreau, C.; Joly, F.; Geoffrois, L.; Ladoire, S.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Nivolumab in Brain Metastases From Renal Cell Carcinoma: Results of the GETUG-AFU 26 NIVOREN Multicenter Phase II Study. JCO 2019, 37, 2008–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.J.; Spigel, D.R.; Gordan, L.N.; Kochuparambil, S.T.; Molina, A.M.; Yorio, J.; Rezazadeh Kalebasty, A.; McKean, H.; Tchekmedyian, N.; Tykodi, S.S.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of First-Line Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab Alternating with Nivolumab Monotherapy in Patients with Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma: The Non-Randomised, Open-Label, Phase IIIb/IV CheckMate 920 Trial. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e058396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, S.B.; Schalper, K.A.; Gettinger, S.N.; Mahajan, A.; Herbst, R.S.; Chiang, A.C.; Lilenbaum, R.; Wilson, F.H.; Omay, S.B.; Yu, J.; et al. Pembrolizumab for Management of Patients with NSCLC and Brain Metastases: Long-Term Results and Biomarker Analysis from a Non-Randomized, Open-Label, Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, M.-O.; Grünwald, V.; Müller-Huesmann, H.; Ivanyi, P.; Schostak, M.; von der Heyde, E.; Schultze-Seemann, W.; Belz, H.; Bögemann, M.; Wang, M.; et al. Real-World Data on the Use of Nivolumab Monotherapy in the Treatment of Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma after Prior Therapy: Interim Results from the Noninterventional NORA Study. Eur. Urol. Focus 2022, 8, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, A.; Stewart, T.F.; Mantia, C.M.; Shah, N.J.; Gatof, E.S.; Long, Y.; Allman, K.D.; Ornstein, M.C.; Hammers, H.J.; McDermott, D.F.; et al. Salvage Ipilimumab and Nivolumab in Patients With Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma After Prior Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3088–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammers, H.J.; Plimack, E.R.; Infante, J.R.; Rini, B.I.; McDermott, D.F.; Lewis, L.D.; Voss, M.H.; Sharma, P.; Pal, S.K.; Razak, A.R.A.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Nivolumab in Combination With Ipilimumab in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: The CheckMate 016 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 3851–3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, L.; Forschner, A.; Loquai, C.; Goldinger, S.M.; Zimmer, L.; Ugurel, S.; Schmidgen, M.I.; Gutzmer, R.; Utikal, J.S.; Göppner, D.; et al. Cutaneous, Gastrointestinal, Hepatic, Endocrine, and Renal Side-Effects of Anti-PD-1 Therapy. Eur. J. Cancer 2016, 60, 190–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, K.; Inoue, M.; Washino, S.; Shirotake, S.; Kagawa, M.; Takeshita, H.; Miura, Y.; Hyodo, Y.; Oyama, M.; Kawakami, S.; et al. Clinical Outcomes of Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Patients with Metastatic Non-Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma: Real-World Data from a Japanese Multicenter Retrospective Study. Int. J. Urol. 2023, 30, 714–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, K.; Leung, H.T.; Fuertes, C.; Mori, M.; Wang, M.; Teo, J.; Weiss, L.; Hamilton, S.; DiFebo, H.; Noh, Y.J.; et al. Nivolumab in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Safety Profile and Select Treatment-Related Adverse Events From the CheckMate 040 Study. Oncologist 2020, 25, e1532–e1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanz, B.A.; Pollack, M.H.; Johnpulle, R.; Puzanov, I.; Horn, L.; Morgans, A.; Sosman, J.A.; Rapisuwon, S.; Conry, R.M.; Eroglu, Z.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Anti-PD-1 in Patients with Baseline Cardiac, Renal, or Hepatic Dysfunction. J. Immunother. Cancer 2016, 4, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, D.J.; Hamieh, L.; McKay, R.R.; Harshman, L.C.; Brandao, R.; Norton, C.K.; Steinharter, J.A.; Krajewski, K.M.; Gao, X.; Schutz, F.A.; et al. Durable Clinical Benefit in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Patients Who Discontinue PD-1/PD-L1 Therapy for Immune-Related Adverse Events. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018, 6, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massard, C.; Gordon, M.S.; Sharma, S.; Rafii, S.; Wainberg, Z.A.; Luke, J.; Curiel, T.J.; Colon-Otero, G.; Hamid, O.; Sanborn, R.E.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Durvalumab (MEDI4736), an Anti–Programmed Cell Death Ligand-1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor, in Patients with Advanced Urothelial Bladder Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 3119–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, J.J.; Kochenderfer, M.D.; Olsen, M.R.; Bauer, T.M.; Molina, A.; Hauke, R.J.; Reeves, J.A.; Babu, S.; Van Veldhuizen, P.; Somer, B.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Nivolumab in Patients with Advanced Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma: Results from the Phase IIIb/IV CheckMate 374 Study. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2020, 18, 469–476.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meraz-Muñoz, A.; Amir, E.; Ng, P.; Avila-Casado, C.; Ragobar, C.; Chan, C.; Kim, J.; Wald, R.; Kitchlu, A. Acute Kidney Injury Associated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: Incidence, Risk Factors and Outcomes. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, T.S.K.; Wu, Y.-L.; Kudaba, I.; Kowalski, D.M.; Cho, B.C.; Turna, H.Z.; Castro, G.; Srimuninnimit, V.; Laktionov, K.K.; Bondarenko, I.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for Previously Untreated, PD-L1-Expressing, Locally Advanced or Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (KEYNOTE-042): A Randomised, Open-Label, Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 1819–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourey, L.; Rainho, L.T.; Dalban, C.; Carril-Ajuria, L.; Negrier, S.; Chevreau, C.; Gravis, G.; Thibault, C.; Laguerre, B.; Barthelemy, P.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Nivolumab in Elderly Patients with Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma: Analysis of the NIVOREN GETUG-AFU 26 Study. Eur. J. Cancer 2024, 201, 113589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noronha, V.; Abraham, G.; Patil, V.; Joshi, A.; Menon, N.; Mahajan, A.; Janu, A.; Jain, S.; Talreja, V.T.; Kapoor, A.; et al. A Real-world Data of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Solid Tumors from India. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 1525–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly, A.; Hughes, P.; Mann, J.; Lai, Z.; Teh, J.J.; Mclean, E.; Edmonds, K.; Lingard, K.; Chauhan, D.; Lynch, J.; et al. An Immunotherapy Survivor Population: Health-Related Quality of Life and Toxicity in Patients with Metastatic Melanoma Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polkowska, M.; Ekk-Cierniakowski, P.; Czepielewska, E.; Kozłowska-Wojciechowska, M. Efficacy and Safety of BRAF Inhibitors and Anti-CTLA4 Antibody in Melanoma Patients—Real-World Data. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 75, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, T.; van der Heijden, M.S.; Castellano, D.; Galsky, M.D.; Loriot, Y.; Petrylak, D.P.; Ogawa, O.; Park, S.H.; Lee, J.-L.; De Giorgi, U.; et al. Durvalumab Alone and Durvalumab plus Tremelimumab versus Chemotherapy in Previously Untreated Patients with Unresectable, Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma (DANUBE): A Randomised, Open-Label, Multicentre, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1574–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Tomczak, P.; Park, S.H.; Venugopal, B.; Ferguson, T.; Symeonides, S.N.; Hajek, J.; Gurney, H.; Chang, Y.-H.; Lee, J.L.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus Placebo as Post-Nephrectomy Adjuvant Therapy for Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (KEYNOTE-564): 30-Month Follow-up Analysis of a Multicentre, Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghav, K.P.; Stephen, B.; Karp, D.D.; Piha-Paul, S.A.; Hong, D.S.; Jain, D.; Chudy Onwugaje, D.O.; Abonofal, A.; Willett, A.F.; Overman, M.; et al. Efficacy of Pembrolizumab in Patients with Advanced Cancer of Unknown Primary (CUP): A Phase 2 Non-Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e004822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassy, E.; Dalban, C.; Colomba, E.; Derosa, L.; Alves Costa Silva, C.; Negrier, S.; Chevreau, C.; Gravis, G.; Oudard, S.; Laguerre, B.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Concomitant Proton Pump Inhibitor and Nivolumab in Renal Cell Carcinoma: Results of the GETUG-AFU 26 NIVOREN Multicenter Phase II Study. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2022, 20, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ready, N.E.; Audigier-Valette, C.; Goldman, J.W.; Felip, E.; Ciuleanu, T.-E.; Rosario García Campelo, M.; Jao, K.; Barlesi, F.; Bordenave, S.; Rijavec, E.; et al. First-Line Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab for Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Including Patients with ECOG Performance Status 2 and Other Special Populations: CheckMate 817. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e006127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1–Positive Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1823–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rini, B.I.; Stein, M.; Shannon, P.; Eddy, S.; Tyler, A.; Stephenson, J.J., Jr.; Catlett, L.; Huang, B.; Healey, D.; Gordon, M. Phase 1 Dose-Escalation Trial of Tremelimumab plus Sunitinib in Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer 2011, 117, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seethapathy, H.; Zhao, S.; Chute, D.F.; Zubiri, L.; Oppong, Y.; Strohbehn, I.; Cortazar, F.B.; Leaf, D.E.; Mooradian, M.J.; Villani, A.-C.; et al. The Incidence, Causes, and Risk Factors of Acute Kidney Injury in Patients Receiving Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 14, 1692–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Callahan, M.K.; Bono, P.; Kim, J.; Spiliopoulou, P.; Calvo, E.; Pillai, R.N.; Ott, P.A.; de Braud, F.; Morse, M.; et al. Nivolumab Monotherapy in Recurrent Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma (CheckMate 032): A Multicentre, Open-Label, Phase 1/2 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 1590–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, S.; Baxi, S.; Torres, A.Z.; Lenis, D.; Freedman, A.N.; Mariotto, A.B.; Sharon, E. Organ Dysfunction in Patients with Advanced Melanoma Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Oncologist 2020, 25, e1753–e1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, C.N.; Loriot, Y.; James, N.; Choy, E.; Castellano, D.; Lopez-Rios, F.; Banna, G.L.; De Giorgi, U.; Masini, C.; Bamias, A.; et al. Primary Results from SAUL, a Multinational Single-Arm Safety Study of Atezolizumab Therapy for Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial or Nonurothelial Carcinoma of the Urinary Tract. Eur. Urol. 2019, 76, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukari, A.; Nagasaka, M.; Alhasan, R.; Patel, D.; Wozniak, A.; Ramchandren, R.; Vaishampayan, U.; Weise, A.; Flaherty, L.; Jang, H.; et al. Cancer Site and Adverse Events Induced by Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Retrospective Analysis of Real-Life Experience at a Single Institution. Anticancer. Res. 2019, 39, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tachibana, H.; Kondo, T.; Ishihara, H.; Fukuda, H.; Yoshida, K.; Takagi, T.; Izuka, J.; Kobayashi, H.; Tanabe, K. Modest Efficacy of Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Patients with Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 51, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tio, M.; Rai, R.; Ezeoke, O.M.; McQuade, J.L.; Zimmer, L.; Khoo, C.; Park, J.J.; Spain, L.; Turajlic, S.; Ardolino, L.; et al. Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 Immunotherapy in Patients with Solid Organ Transplant, HIV or Hepatitis B/C Infection. Eur. J. Cancer 2018, 104, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, Y.; Fukasawa, S.; Shinohara, N.; Kitamura, H.; Oya, M.; Eto, M.; Tanabe, K.; Saito, M.; Kimura, G.; Yonese, J.; et al. Nivolumab versus Everolimus in Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma: Japanese Subgroup 3-Year Follow-up Analysis from the Phase III CheckMate 025 Study. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 49, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tykodi, S.S.; Gordan, L.N.; Alter, R.S.; Arrowsmith, E.; Harrison, M.R.; Percent, I.; Singal, R.; Van Veldhuizen, P.; George, D.J.; Hutson, T.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Patients with Advanced Non-Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma: Results from the Phase 3b/4 CheckMate 920 Trial. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e003844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudev, N.S.; Ainsworth, G.; Brown, S.; Pickering, L.; Waddell, T.; Fife, K.; Griffiths, R.; Sharma, A.; Katona, E.; Howard, H.; et al. Standard Versus Modified Ipilimumab, in Combination with Nivolumab, in Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Randomized Phase II Trial (PRISM). J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhaart, S.L.; Abu-Ghanem, Y.; Mulder, S.F.; Oosting, S.; Van Der Veldt, A.; Osanto, S.; Aarts, M.J.B.; Houtsma, D.; Peters, F.P.J.; Groenewegen, G.; et al. Real-World Data of Nivolumab for Patients With Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma in the Netherlands: An Analysis of Toxicity, Efficacy, and Predictive Markers. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2021, 19, 274.e1–274.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelzang, N.J.; Olsen, M.R.; McFarlane, J.J.; Arrowsmith, E.; Bauer, T.M.; Jain, R.K.; Somer, B.; Lam, E.T.; Kochenderfer, M.D.; Molina, A.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Nivolumab in Patients with Advanced Non–Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma: Results From the Phase IIIb/IV CheckMate 374 Study. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2020, 18, 461–468.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.J.; Kumarakulasinghe, N.B.; Muthu, V.; Lee, M.; Walsh, R.; Low, J.L.; Choo, J.; Tan, H.L.; Chong, W.Q.; Ang, Y.; et al. Low-Dose Nivolumab in Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Real-World Experience. Oncology 2021, 99, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Liu, B.; Shen, N.; Fan, X.; Lu, S.; Kong, Z.; Gao, Y.; Lv, Z.; Wang, R. Acute Kidney Injury in Patients Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Ren. Fail. 2024, 46, 2326186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belliere, J.; Mazieres, J.; Meyer, N.; Chebane, L.; Despas, F. Renal Complications Related to Checkpoint Inhibitors: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Strategies. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, M.J.; Larkin, J.M.G. Novel Combination Strategies for Enhancing Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in the Treatment of Metastatic Solid Malignancies. Expert. Opin. Pharmacother. 2017, 18, 1477–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, F.; Martín de Francisco, Á.L.M.; Auñón, P.; García-Carro, C.; García, P.; Gutiérrez, E.; Mcía, M.; Quintana, L.F.; Quiroga, B.; Soler, M.J.; et al. Adverse Renal Effects of Check-Point Inhibitors (ICI) in Cancer Patients: Recommendations of the Onco-Nephrology Working Group of the Spanish Society of Nephrology. Nefrología 2023, 43, 622–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho-Martínez, S.M.; Prieto, L.; Blanco-Gozalo, V.; Fontecha-Barriuso, M.; Vicente-Vicente, L.; Casanova, A.G.; Prieto, M.; Pescador, M.; Morales, A.I.; López-Novoa, J.M.; et al. Acute Tubular Necrosis: An Old Term in Search for a New Meaning within the Evolving Concept of Acute Kidney Injury. N. Horiz. Transl. Med. 2015, 2, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moledina, D.G.; Perazella, M.A. The Challenges of Acute Interstitial Nephritis: Time to Standardize. Kidney360 2021, 2, 1051–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinmann, S.C.; Pisetsky, D.S. Mechanisms of Immune-Related Adverse Events during the Treatment of Cancer with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Rheumatology 2019, 58, vii59–vii67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.S.; D’Angelo, S.P.; Minor, D.; Hodi, F.S.; Gutzmer, R.; Neyns, B.; Hoeller, C.; Khushalani, N.I.; Miller, W.H.; Lao, C.D.; et al. Nivolumab versus Chemotherapy in Patients with Advanced Melanoma Who Progressed after Anti-CTLA-4 Treatment (CheckMate 037): A Randomised, Controlled, Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, C.; Schachter, J.; Long, G.V.; Arance, A.; Grob, J.J.; Mortier, L.; Daud, A.; Carlino, M.S.; McNeil, C.; Lotem, M.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2521–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belliere, J.; Meyer, N.; Mazieres, J.; Ollier, S.; Boulinguez, S.; Delas, A.; Ribes, D.; Faguer, S. Acute Interstitial Nephritis Related to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 115, 1457–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotte, A. Combination of CTLA-4 and PD-1 Blockers for Treatment of Cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, R.V.; Chemnitz, J.M.; Frauwirth, K.A.; Lanfranco, A.R.; Braunstein, I.; Kobayashi, S.V.; Linsley, P.S.; Thompson, C.B.; Riley, J.L. CTLA-4 and PD-1 Receptors Inhibit T-Cell Activation by Distinct Mechanisms. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 25, 9543–9553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmamed, M.F.; Chen, L. A Paradigm Shift in Cancer Immunotherapy: From Enhancement to Normalization. Cell 2018, 175, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Short, S.A.P.; Sise, M.E.; Prosek, J.M.; Madhavan, S.M.; Soler, M.J.; Ostermann, M.; Herrmann, S.M.; Abudayyeh, A.; Anand, S.; et al. Acute Kidney Injury in Patients Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e003467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumoulin, D.W.; Visser, S.; Cornelissen, R.; van Gelder, T.; Vansteenkiste, J.; von der Thusen, J.; Aerts, J.G.J.V. Renal Toxicity From Pemetrexed and Pembrolizumab in the Era of Combination Therapy in Patients With Metastatic Nonsquamous Cell NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2020, 15, 1472–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).