Surface and Biocompatibility Outcomes of Chemical Decontamination in Peri-Implantitis Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiment Protocol

2.2. Atomic Force Microscopy

2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. AFM Assessment

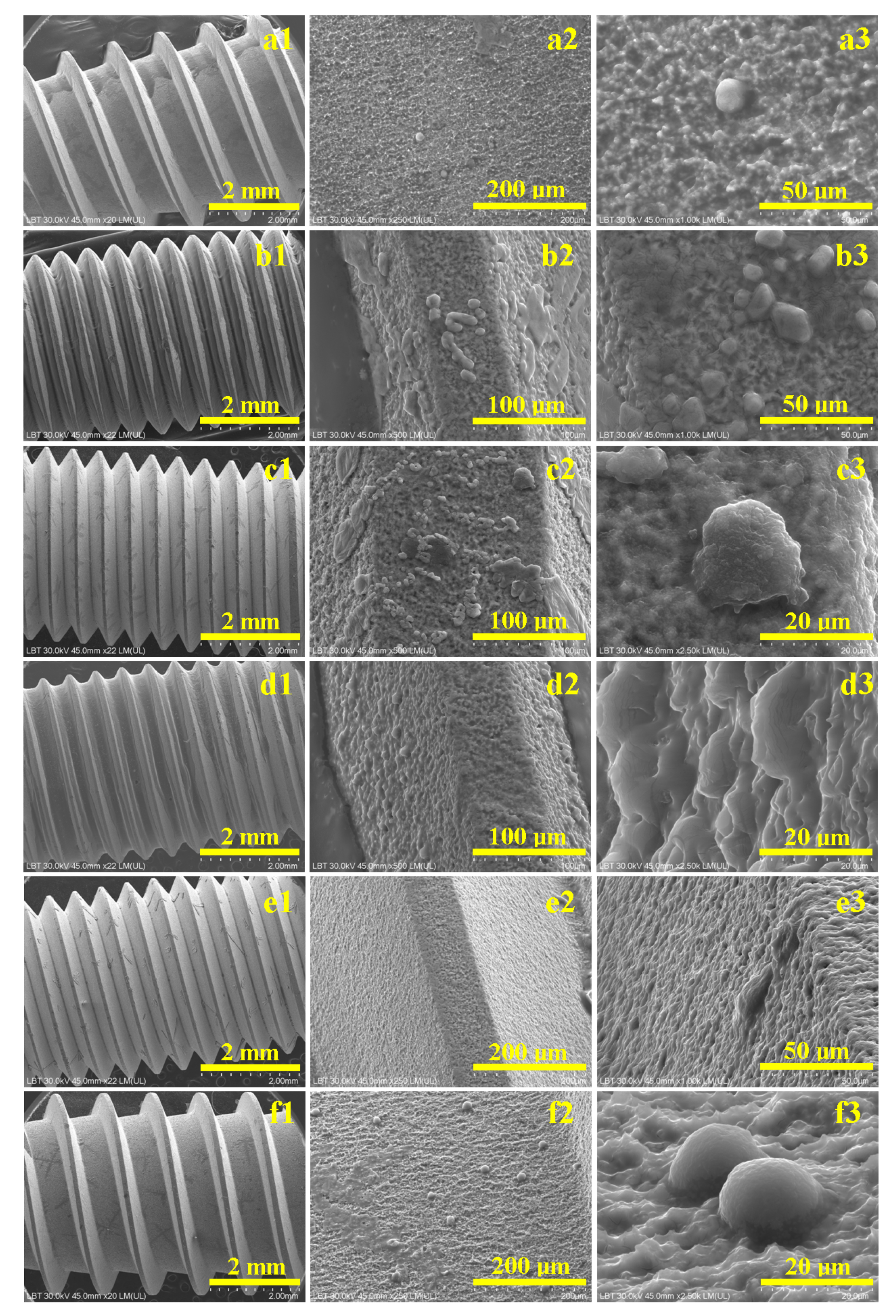

3.2. SEM Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berglundh, T.; Persson, L.; Klinge, B. A systematic review of the incidence of biological and technical complications in implant dentistry. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2002, 29, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, J.; Tomasi, C. Peri-implant health and disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, S158–S171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, F.; Derks, J.; Monje, A.; Wang, H.L. Peri-implantitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, S246–S266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renvert, S.; Roos-Jansåker, A.M.; Claffey, N. Non-surgical treatment of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis: A literature review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2008, 35, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggion, C.M., Jr.; Petersilka, G.; Lange, D.E.; Gerss, J.; Flemmig, T.F. Prognostic factors for clinical periodontal treatment outcomes. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2014, 41, 550–560. [Google Scholar]

- Carcuac, O.; Derks, J.; Charalampakis, G.; Abrahamsson, I.; Wennström, J.L.; Berglundh, T. Adjunctive systemic and local antimicrobial therapy in the surgical treatment of peri-implantitis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, F.; Sahm, N.; Becker, J. Combined surgical therapy of advanced peri-implantitis evaluating two methods of surface decontamination: A 12-month clinical follow-up study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2011, 38, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntrouka, V.I.; Hoogenkamp, M.A.; Zaura, E.; van der Weijden, F.A. The effect of chemotherapeutic agents on titanium-adherent biofilms. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2011, 22, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albouy, J.P.; Abrahamsson, I.; Persson, L.G.; Berglundh, T. Spontaneous progression of peri-implantitis at different types of implants: An experimental study in dogs. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2008, 35, 228–235. [Google Scholar]

- Ramel, C.F.; Lussi, A.; Özcan, M.; Jung, R.E.; Hämmerle, C.H.; Thoma, D.S. Surface alterations of titanium discs after different chemical and mechanical cleaning protocols: An in vitro study. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2019, 30, 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sahrmann, P.; Ronay, V.; Hofer, D.; Attin, T.; Jung, R.E.; Schmidlin, P.R. In vitro cleaning potential of three different implant decontamination methods. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2015, 26, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tisler, C.E.; Moldovan, M.; Petean, I.; Buduru, S.D.; Prodan, D.; Sarosi, C.; Leucuţa, D.-C.; Chifor, R.; Badea, M.E.; Ene, R. Human Enamel Fluorination Enhancement by Photodynamic Laser Treatment. Polymers 2022, 14, 2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avram, S.E.; Tudoran, L.B.; Borodi, G.; Petean, I. Microstructural Characterization of the Mn Lepidolite Distribution in Dark Red Clay Soils. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardelean, A.I.; Dragomir, M.F.; Moldovan, M.; Sarosi, C.; Paltinean, G.A.; Pall, E.; Tudoran, L.B.; Petean, I.; Oana, L. In Vitro Study of Composite Cements on Mesenchymal Stem Cells of Palatal Origin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zeng, W.; Sun, Y.; Han, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, P. Microstructure-Tensile Properties Correlation for the Ti-6Al-4V Titanium Alloy. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2015, 24, 1754–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Song, Y.; He, Y.; Wei, C.; Chen, R.; Guo, S.; Liang, W.; Lei, S.; Liu, X. Evolution of Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Ti-6Al-4V Alloy under Heat Treatment and Multi-Axial Forging. Materials 2024, 17, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtaszek, M.; Korpała, G.; Śleboda, T.; Zyguła, K.; Prahl, U. Hot Processing of Powder Metallurgy and Wrought Ti-6Al-4V Alloy with Large Total Deformation: Physical Modeling and Verification by Rolling. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2020, 51, 5790–5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeraya-Calderón, F.; Jáquez-Muñoz, J.M.; Lara-Banda, M.; Zambrano-Robledo, P.; Cabral-Miramontes, J.A.; Lira-Martínez, A.; Estupinán-López, F.; Gaona Tiburcio, C. Corrosion Behavior of Titanium and Titanium Alloys in Ringer’s Solution. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2022, 17, 220751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neaga, V.; Benea, L.; Axente, E.R. Corrosion Assessment of Zr2.5Nb Alloy in Ringer’s Solution by Electrochemical Methods. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guleryuz, H.; Cimenoglu, H. Oxidation of Ti–6Al–4V alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 472, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahveci, A.I.; Welsch, G.E. Effect of oxygen on the hardness and alpha/beta phase ratio of Ti 6A1 4V alloy. Scr. Metall. 1986, 20, 1287–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tăut, M.A.; Moldovan, M.; Filip, M.; Petean, I.; Saroşi, C.; Cuc, S.; Taut, A.C.; Ardelean, I.; Lazăr, V.; Man, S.C. Synthesis and Characterization of Microcapsules as Fillers for Self-Healing Dental Composites. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moldovan, M.; Dudea, D.; Cuc, S.; Sarosi, C.; Prodan, D.; Petean, I.; Furtos, G.; Ionescu, A.; Ilie, N. Chemical and Structural Assessment of New Dental Composites with Graphene Exposed to Staining Agents. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, A.M.; Azambuja, D.S. Electrochemical behavior of Ti and Ti6Al4V in aqueous solutions of citric acid containing halides. Mater. Res. 2006, 9, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leban, M.B.; Kosec, T.; Finšgar, M. The corrosion resistance of dental Ti6Al4V with differing microstructures in oral environments. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 1982–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, L.; Genova, C.; Stagno, V.; Paoletti, L.; Matulac, A.L.; Ciccola, A.; Di Fazio, M.; Capuani, S.; Favero, G. Multi-Technique Assessment of Chelators-Loaded PVA-Borax Gel-like Systems Performance in Cleaning of Stone Contaminated with Copper Corrosion Products. Gels 2024, 10, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wang, L.; Kang, G.; Lin, X.; Tian, L.; Guo, P.; Wu, L.; Huang, W. Effects of electrolytes on electrochemical behaviour and performance of Ti6Al4V alloy prepared by laser directed energy deposition. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 35, 1913–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Cadena, A.; García-Blanco, M.B.; Reschenhofer, B.; Barreneche, C.; Skerbis, P.; Leitl, P.A.; Santamaría, P.; Roa, J.J. In-depth study of the dry-anodizing process on Ti6Al4V alloys: Effect of the acid content and electrical parameters. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 499, 131767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Sinha, A.; Chattopadhyay, S. Corrosion behavior of titanium and its alloys in simulated physiological environments: A comprehensive review. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H J. Eng. Med. 2023, 237, 753–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Anand, S.; Kumar, P. Surface degradation mechanisms of biomedical titanium alloys under corrosive and mechanical environments: Insights from recent advances. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H J. Eng. Med. 2023, 237, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrir, H.; Layachi, O.A.; Boudouma, A.; El Bouari, A.; Sidimou, A.A.; El Marrakchi, M.; Khoumri, E. Electrochemical corrosion behavior of α-titanium alloys in simulated biological environments (comparative study). RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 38110–38119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, G.; Xu, Q. Review on the fabrication of surface functional structures for enhancing bioactivity of titanium and titanium alloy implants. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2024, 37, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mester, A.; Bran, S.; Moldovan, M.; Petean, I.; Tudoran, L.B.; Sarosi, C.; Piciu, A.; Ene, D. Surface and Biocompatibility Outcomes of Chemical Decontamination in Peri-Implantitis Management. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2748. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112748

Mester A, Bran S, Moldovan M, Petean I, Tudoran LB, Sarosi C, Piciu A, Ene D. Surface and Biocompatibility Outcomes of Chemical Decontamination in Peri-Implantitis Management. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(11):2748. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112748

Chicago/Turabian StyleMester, Alexandru, Simion Bran, Marioara Moldovan, Ioan Petean, Lucian Barbu Tudoran, Codruta Sarosi, Andra Piciu, and Dragos Ene. 2025. "Surface and Biocompatibility Outcomes of Chemical Decontamination in Peri-Implantitis Management" Biomedicines 13, no. 11: 2748. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112748

APA StyleMester, A., Bran, S., Moldovan, M., Petean, I., Tudoran, L. B., Sarosi, C., Piciu, A., & Ene, D. (2025). Surface and Biocompatibility Outcomes of Chemical Decontamination in Peri-Implantitis Management. Biomedicines, 13(11), 2748. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112748