Abstract

Glaucoma is one of the leading causes of permanent vision loss worldwide and has a profound impact on patients’ quality of life. Vision impairment is strongly associated with several psychiatric disorders, like depression, anxiety, and sleep problems. These psychiatric issues are often exacerbated by the gradual, irreversible, and typically silent progression of the disease, contributing to increased mental health challenges for affected individuals. A systematic review was conducted following PRISMA guidelines across six different databases (CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Web of Science, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library) and one gray literature source (Google Scholar), covering the period from 2013 to 2024. Twenty-nine studies involving a total of 13,326,845 subjects were included in the synthesis, highlighting a considerable prevalence of psychiatric disorders among glaucoma patients. Depression and anxiety were the most common conditions identified, with depression rates ranging from 6.6% to 57% and anxiety from 12.11% to 49%. Other less frequent but still significant conditions like sleep disorders, psychosis, dementia, and post-traumatic stress disorder were also observed. The findings also indicated that psychiatric severity was influenced by socio-demographic factors, glaucoma severity, and treatment duration. Given the high occurrence of psychiatric pathologies among individuals with glaucoma, it is essential to develop comprehensive care strategies that address both eye and mental health needs. Multidisciplinary collaboration among ophthalmologists, psychiatrists, psychologists, and primary care physicians is crucial for developing personalized treatment plans that effectively manage both the ocular and psychological aspects of the disease.

1. Introduction

Glaucoma is a major cause of permanent vision loss worldwide, currently affecting more than 76 million individuals, a number expected to rise to 111.8 million by the year 2040 [1]. Chronic illnesses are extensively documented to have a detrimental effect on mental health, with conditions like diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer often linked to higher rates of depression and anxiety [2]. As a chronic disease, the correlation between glaucoma and psychological illnesses is complex and multifaceted. The disease not only causes vision impairment but also has a severe impact on patients’ quality of life and presents considerable socioeconomic issues. The psychological effects experienced by people suffering from glaucoma are significant, occurring alongside the physical symptoms of the condition [3,4]. Impaired vision can lead to a deep sense of reliance, diminished independence, and reduced social engagement [5]. Researchers suggests that individuals with visual impairments are nearly twice as likely to experience depression compared to those without visual problems [6]. These conditions can be exacerbated by the challenges experienced by people with glaucoma, impacting their quality of life, adherence to therapy, and general outlook [7,8]. The gradual and often silent progression of glaucoma can result in notable tension and anxiety, primarily due to the fear of eventual loss of vision. Studies have indicated that around 40% of individuals diagnosed with glaucoma suffer from anxiety, and approximately 20% experience depression rates that are significantly higher than those observed in the general population [9].

Despite the extensive documentation of psychiatric issues in other chronic conditions, the relationship between glaucoma and psychiatric disorders has not been fully elucidated, leaving a gap in the current literature. Existing reviews, while insightful, have not consistently explored the potential mechanisms linking glaucoma and mental health disturbances. There is a need to delve deeper into how glaucoma could affect the brain areas associated with mood regulation, stress responses, and psychological resilience. This exploration is crucial for uncovering not only the prevalence of these psychiatric issues but also the underlying pathways that may drive these associations.

To fully understand the extent of psychiatric disorders in individuals with glaucoma, it is essential to recognize the reciprocal connection between these conditions. Emerging research suggests that glaucoma may not only induce psychological disorders due to the visual impairment it causes but may also be influenced by psychiatric conditions that exacerbate its progression, creating a cycle of physical and mental decline. Additionally, brain regions involved in both vision and emotional regulation, such as the occipital cortex and limbic system, may be implicated in this relationship, further complicating the disease’s impact on mental health. Previous research on this topic has been dispersed, exhibiting differences in their approaches, sample sizes, and geographical scopes. Understanding the interaction between glaucoma and psychological problems is essential for developing comprehensive treatment strategies. By combining mental health care with eye care, treatment adherence can be improved, quality of life can be enhanced, and the disease’s progression can potentially be slowed [10].

Our systematic review aims to analyze and evaluate the current body of research on psychological disorders in individuals with glaucoma, gathering and summarizing the existing research, providing a comprehensive examination of the frequency, categories, and consequences of mental problems in people with glaucoma. In addition, we also aim to contribute new insights regarding the biological pathways that may link psychological stress and glaucoma progression, emphasizing the need for a more integrative approach in research and clinical practice. Specifically, the main objectives of the study are (1) to assess the prevalence of psychological conditions in individuals diagnosed with glaucoma; (2) to classify the psychiatric illnesses frequently linked to glaucoma; (3) to explore possible mechanisms linking glaucoma progression to brain areas involved in mood regulation and how stress-related hormonal changes may exacerbate glaucoma; (4) to analyze the impact of various mental health conditions on the treatment of glaucoma and patient outcomes; and (5) to identify gaps in the current body of knowledge and suggest potential areas for future research.

Through this investigation, our goal is to enhance the understanding of the difficulties experienced by individuals with glaucoma and encourage the implementation of more efficient and coordinated care approaches. Additionally, we aim to identify notable trends and discrepancies in the prevalence and impact of psychiatric disorders among glaucoma patients by analyzing newer studies from Africa, Asia, Europe, and North America and from underrepresented regions, and with unique socio-demographic contexts.

Therefore, this review will be an important resource for clinicians, academics, and policymakers, highlighting the importance of a multidisciplinary approach for managing glaucoma that includes mental health support.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted according to the PRISMA 2020 Guidelines and registered the systematic review project via Open Science Framework (OSF) with the following site doi: 10.17605/OSF.IO/WP7J8.

2.1. Search Strategy

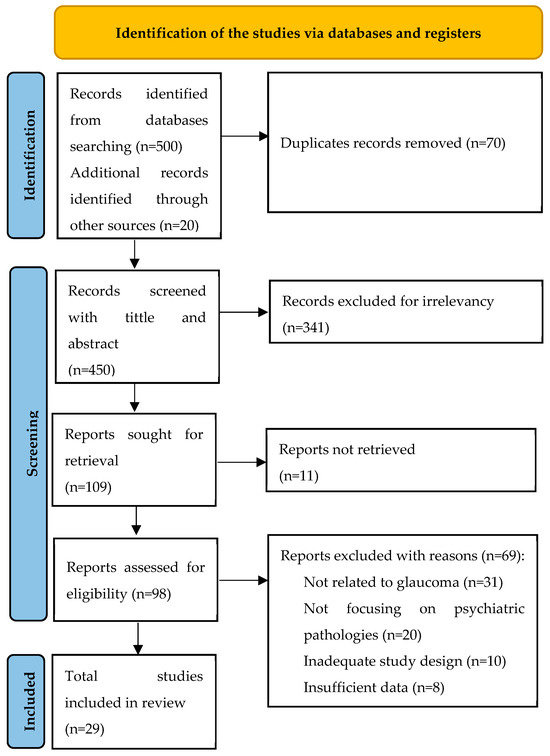

The search strategy for this systematic literature review was designed to capture a wide range of research on psychiatric pathologies in the glaucoma population. Searches were conducted and reviewed independently by three authors (initials of authors: J.J., J.A. and J.M.B.), ensuring comprehensive coverage. In cases of disagreement, a fourth author (D.M./I.R.) resolved the conflicts. Searches were comprehensively conducted across six electronic databases: CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Web of Science, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library. Additionally, to minimize publication bias, the articles search was comprehensively conducted in Google Scholar to trace and review both scholarly sources and gray literature [11]. The search strategy included articles published since 2013. The Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) search terms used were “glaucoma”, “psychiatric disorders”, “mental health”, “depression”, “anxiety”, and “psychological distress”. Boolean operators (AND, OR) were utilized to refine and expand the search as necessary. Additionally, we also reviewed the reference lists of relevant articles and conducted manual searches of key journals to identify any studies that might have been missed in the database searches. To ensure that the selection process was transparent and reproducible, duplicate records were removed using reference management software, and a two-step screening process was implemented: (1) titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, and (2) full texts of potentially relevant studies were reviewed in detail against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The literature selection was represented in PRISMA model at Figure 1 and the relevant selected articles are explained in the data extraction table—Table 1. After the data collection process, a meta-analysis of all the selected studies was performed using the IBM SPSS version 30 software.

Figure 1.

PRISMA model of the literature selection.

Table 1.

Data extraction table.

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria for this systematic literature review encompassed studies published between 2013 and 2024 that investigated the prevalence, incidence, or impact of psychiatric pathologies, such as depression, anxiety, or psychological distress, in populations diagnosed with glaucoma. Eligible studies included various study designs, such as randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, case–control studies, and cross-sectional studies. Participants needed to have a clinical diagnosis of any type of glaucoma (e.g., primary open-angle glaucoma, primary angle-closure glaucoma). Studies published in English were included, with no restrictions on geographic location or healthcare settings. Exclusion criteria were defined with particular care to avoid confounding factors that could impact the results. Studies focusing on populations with significant comorbidities, including cardiovascular diseases, metabolic disorders (e.g., diabetes), and severe neurological disorders, were excluded. This decision was made to ensure that any observed psychiatric symptoms were primarily attributable to glaucoma and not to other chronic or progressive conditions. To ensure the reliability of the results, studies that did not assess psychiatric outcomes, case reports, editorials, commentaries, and studies with insufficient methodological quality or data were excluded.

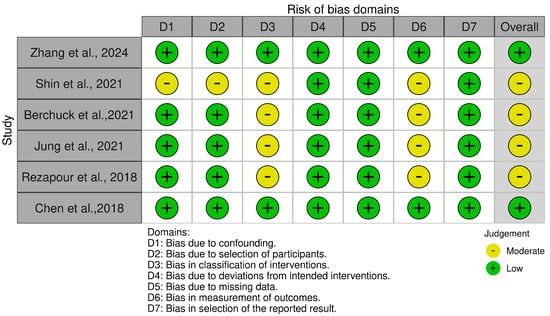

2.3. Risk of Bias

In this systematic review, a comprehensive risk of bias assessment was conducted for all included studies to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings. A total of 29 studies were evaluated using appropriate risk of bias tools based on study design. Specifically, the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool was applied to six cohort studies. The ROBINS-I tool evaluates risk of bias across seven domains: confounding factors, selection of participants, classification of interventions, deviations from intended interventions, missing data, measurement of outcomes, and selection of the reported result, providing a comprehensive assessment of potential biases in non-randomized studies.

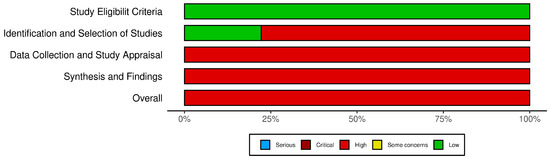

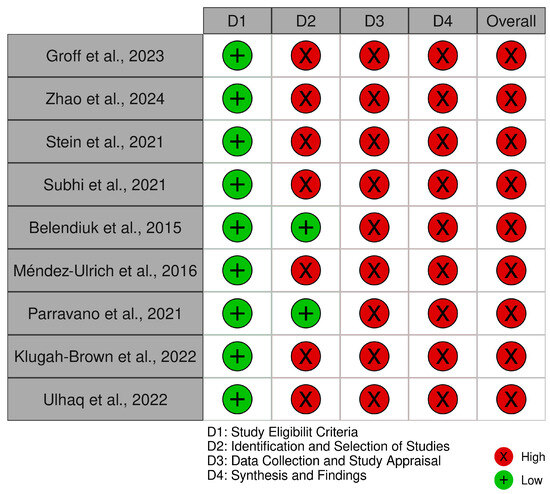

For nine systematic reviews included in the analysis, the Risk of Bias In Systematic Reviews (ROBIS) tool was used. This tool assesses bias across four phases: assessing relevance, identifying concerns with the review process (study identification, selection, data collection, and synthesis), and judging the overall risk of bias in the context of the systematic review methodology.

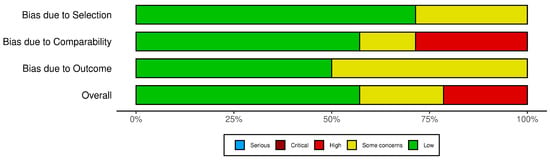

For the remaining 14 cross-sectional and case–control studies, the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was employed. This scale evaluates risk of bias across three broad categories: selection (representativeness of cases/controls, selection of controls, and exposure ascertainment), comparability (controlling for key confounders), and outcome/exposure assessment. Each category is rated to determine overall study quality and potential sources of bias.

3. Results

The 29 studies included in this study focus on diverse populations, including glaucoma patients with various disease severities, veterans, and elderly individuals (n = 13,326,845). They encompass a range of geographic regions (e.g., Japan, Taiwan, USA, Europe, and Ethiopia), employing diverse study designs, including cross-sectional, case–control, cohort, and systematic review designs. The most frequently studied psychiatric disorders were anxiety, depression, PTSD, sleep disorders, cognitive impairment, and common mental disorders (CMDs).

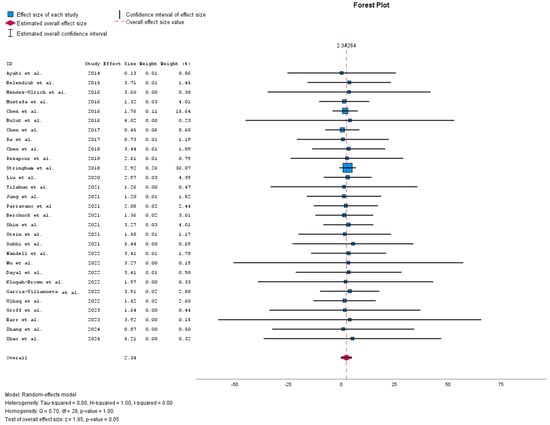

Figure 2 shows the meta-analysis forest plot depicting the effect sizes of multiple studies included in a meta-analysis, each contributing to the overall estimated effect size. The confidence intervals of individual studies vary, indicating less certainty in their estimates. The estimated overall effect size is around 2.39 with a confidence interval that does not cross zero, suggesting a statistically significant effect. Additionally, the heterogeneity results show substantial variability among the studies included in this meta-analysis. The random-effects model used accounts for this heterogeneity, implying that the effect sizes differ across studies beyond random chance, possibly because of the differences in study populations or methodologies.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis forest plot [6,9,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38].

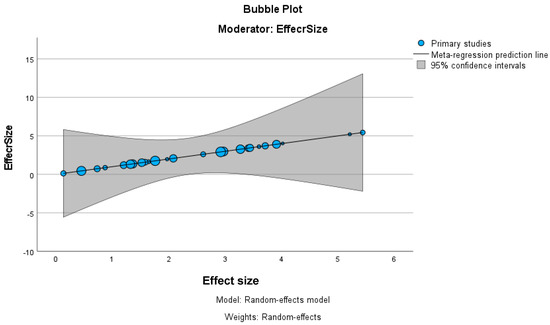

The bubble plot in Figure 3, using effect size as a moderator, visually represents the relationship between effect sizes across primary studies included in the meta-regression. The plot shows a positive slope in the regression line, indicating a potential increase in effect size across studies. When larger effect sizes occur, there is considerable variability in these estimates.

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis bubble plot.

The studies utilized diverse assessment instruments and procedures to evaluate psychiatric diseases in individuals with glaucoma. The commonly used assessment tools included the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [39], the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [40], the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale [41], and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [42].

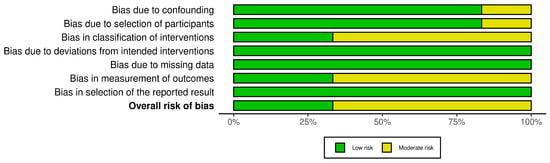

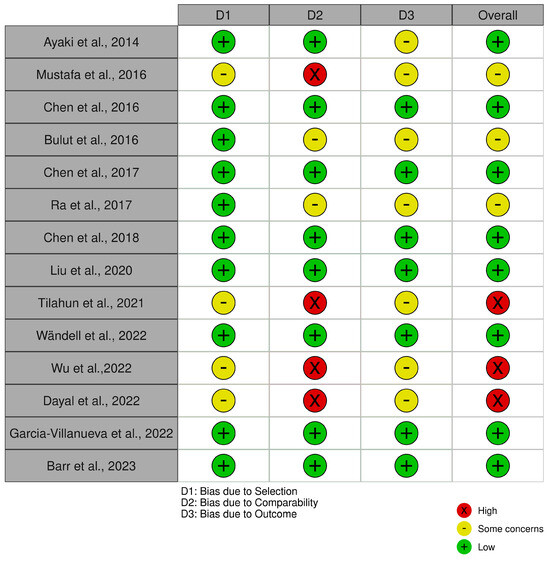

The risk of bias assessment for all the 29 studies included in this systematic review was performed using three tools tailored to the study designs: ROBINS-I (Risk of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions) for six cohort studies, ROBIS (Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews) for nine systematic reviews, and the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for 14 cross-sectional and case–control studies.

For the ROBINS-I tool (Figure 4), the cohort studies displayed a predominantly low risk of bias across domains, including confounding factors, participant selection, and deviations from intended interventions. However, moderate risk of bias was observed in some studies concerning the classification of interventions and measurement of outcomes, largely due to reliance on administrative and self-reported data. The traffic light plot that visually represents the overall risk of bias for each study is showed in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

The ROBINS-I tool.

Figure 5.

The ROBINS-I traffic light plot [20,21,25,26,27,37].

The ROBIS assessment for systematic reviews (Figure 6) identified notable areas of bias. While the ‘Study Eligibility Criteria’ domain generally showed low risk, the ‘Identification and Selection of Studies’, ‘Data Collection and Study Appraisal’, and ‘Synthesis and Findings’ domains demonstrated a high to critical risk of bias. This was attributed to inconsistencies in study selection, insufficient data collection protocols, and limitations in synthesizing findings, which may influence the reliability of systematic review conclusions. The traffic light plot corresponding to the risk of bias for each study is showed in Figure 7.

Figure 6.

The ROBIS tool.

Figure 7.

The ROBIS traffic light plot [6,9,13,14,28,29,33,35,38].

In the evaluation using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) (Figure 8), the cross-sectional and case–control studies were assessed across domains related to selection, comparability, and outcome assessment. The traffic light plot that represents the overall risk of bias for each study is showed in Figure 9.

Figure 8.

The NOS tool.

Figure 9.

The NOS traffic light plot [12,15,16,17,23,24,30,31,32,34,36].

So overall, while many studies demonstrated strong control of confounding factors and robust data management, issues related to study selection, exposure measurement, and the synthesis of findings were observed, particularly among the systematic reviews and certain cross-sectional studies.

Regarding the analysis of 29 studies conducted in different locations and involving diverse populations, it is evident that there is a significant occurrence of psychological disorders among glaucoma patients. Generally, glaucoma becomes more prevalent with age, affecting an estimated 3.54% of the global population between the ages of 40 and 80 [43].

Depression and anxiety are the most common psychiatric diseases within this group, compared to normal individuals, with depression rates ranging from 6.6% to 57% and anxiety rates from 12.11% to 49% [43].

Depression is commonly identified as a comorbid condition in the retrieved articles analyzed. The meta-analysis conducted by Groff et al. (2023) [9] demonstrated a greater occurrence and intensity of depression among those diagnosed with glaucoma. In their study, Chen et al. (2018) [20] found that glaucoma patients had a considerably higher risk of developing depression compared to the control group. The occurrence of depression showed notable variations in the research. Regarding depression treatments, particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), Chen et al. (2016, 2017) [16,18], found that individuals with glaucoma were significantly more likely to have been exposed to SSRIs compared to the general population. Additionally, individuals receiving SSRI therapy for Major Depressive Disorder may be at an elevated risk for any type of glaucoma, especially those between the ages of 32 and 70 years, at higher doses (>20 mg) and with long-term use (>365 days). For those who were prescribed SSRIs, there was a 5.80-fold increased risk of acute angle closure glaucoma within the next seven days.

Glaucoma patients frequently report experiencing anxiety. Research conducted by Groff et al. (2023) [9] and Ulhaq et al. (2024) [35] has shown a significant occurrence of anxiety, with combined prevalence rates of 31.2% for symptoms of anxiety and 19.0% for diagnosed anxiety disorders. Furthermore, pediatric glaucoma patients had significantly elevated levels of anxiety (58.6%) compared to adults (29%) [35,44].

Additionally, sleep disturbances are also common among glaucoma patients. Groff et al. (2023) [9] documented a greater incidence of sleep disorders in this group. A study conducted by Ayaki et al. (2014) [12] revealed that those suffering from advanced glaucoma experienced significantly poorer sleep quality in comparison to the control group. Their study also identified a strong association between the severity of glaucoma and sleep quality.

Finally, psychiatric disorders such as psychosis, dementia, and PTSD were investigated less frequently but still documented in several studies. Wändell et al. (2022) [30] discovered a reduced likelihood of primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) in individuals of both genders who had dementia. Additionally, they observed that women with psychosis exhibited a decreased risk of developing POAG. Stringham et al. (2024) [22] linked PTSD to reduced adherence to glaucoma treatment in military veterans.

Putting all the findings together, our results identify notable trends and discrepancies in the prevalence and impact of psychiatric disorders among glaucoma patients. These data are shown in Table 2. Western populations report higher rates of diagnosed depression and anxiety, while resource-limited regions face greater systemic barriers. Additionally, disease severity universally correlates with worse psychiatric outcomes, though early-stage glaucoma is linked to higher anxiety in younger populations.

Table 2.

Trends in psychiatric comorbidities among glaucoma patients.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Interplay Between Glaucoma and Mental Health

The review highlights the profound impact of glaucoma on mental health, with findings indicating a significant association between glaucoma and various psychiatric disorders, including depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances. The underlying mechanisms for this association are multifaceted, involving biological, psychological, and social factors. Factors such as the severity of glaucoma, the duration of treatment, and concomitant visual impairment were identified as key determinants of the prevalence and severity of psychiatric conditions. Additionally, the data showed that stress is a critical factor influencing both psychological well-being and the progression of chronic diseases like glaucoma. The interplay between stress-related hormonal pathways and glaucoma can exacerbate disease progression through mechanisms such as cortisol dysregulation, altered autonomic function, and neuroinflammation [45]. On one hand, chronic stress results in dysregulated cortisol levels, upregulating glucocorticoid receptors in the trabecular meshwork, reducing aqueous humor outflow and raising intraocular pressure (IOP) [46]. Additionally, this impaired homeostasis, and the exacerbation of the disease progression stress leads to a hyperactivation of the sympathetic nervous system, causing increased vascular resistance and reduced perfusion to the optic nerve head, which can worsen optic nerve damage. On the other hand, it contributes to parasympathetic suppression, which affects the body’s ability to recover from stress and maintain normal IOP and vascular homeostasis, and stimulates the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, TNF-α), which can impair optic nerve function by increasing glial cell activation and disrupt the blood–retinal barrier, compounding retinal and optic nerve damage [46].

4.2. Depression and Antidepressant Use

Patients with glaucoma are at a significantly higher risk of developing depression, reflecting the substantial psychosocial burden associated with visual impairment [5]. Evidence suggests that individuals with glaucoma are more likely to be prescribed selective SSRIs compared to the general population, likely as a reactive approach to managing the psychological impact of the disease. However, many antidepressants, including SSRIs, are contraindicated for glaucoma patients due to their potential to increase IOP, particularly in those predisposed to angle-closure glaucoma [47]. For instance, SSRIs have been linked to a 5.80-fold increase in the risk of acute angle-closure glaucoma within seven days of use in susceptible individuals [47,48,49].

Given this risk, it is imperative to consider newer antidepressants that lack atropine-like side effects. Collaborative care between ophthalmologists and mental health providers is essential to monitor ocular health and ensure safe adjustments to psychiatric medications. Such strategies would help mitigate the risks associated with SSRI use while ensuring effective management of depression [8].

4.3. Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety is also significantly more prevalent among individuals with glaucoma compared to healthy individuals. These findings highlight the mental strain glaucoma places on patients, adding to their physical and emotional burden. The higher prevalence of anxiety in younger patients suggests that early diagnosis and the lifelong management of the disease may trigger heightened anxiety in children and adolescents [3,50]. Considering that many anxiolytics are also contraindicated due to their potential to elevate IOP, alternative therapies, such as cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT), lifestyle changes, and newer medications with lower IOP risks, should be explored [49,51]. These strategies can help reduce reliance on medications that might aggravate glaucoma while effectively managing anxiety symptoms [51].

4.4. Sleep Disturbances

Sleep disturbances were also found to be more common among glaucoma patients. These problems could be driven by the physical discomfort and stress related to visual decline, which in turn worsens the patient’s quality of life. Additionally, a strong association was identified between the severity of glaucoma and sleep quality [9,52]. This suggests that as the disease progresses, sleep disturbances may become more prevalent, possibly due to increased anxiety and visual impairment. Addressing these sleep issues with non-pharmacological approaches, such as sleep hygiene techniques and mindfulness practices, could play an essential role in improving both the physical and mental health outcomes of glaucoma patients [51].

4.5. Other Psychiatric Conditions

While less frequently studied, conditions such as psychosis, dementia, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were also reported in glaucoma patients. The relationship between psychosis and glaucoma may involve complex neurological and pharmacological interactions. Similarly, PTSD may result in decreased treatment adherence, exacerbating visual decline. The potential relationship between glaucoma and dementia raises questions about neurodegenerative processes and their interplay with disease progression [53,54]. These findings highlight the need for specialized mental health interventions tailored to these vulnerable populations.

4.6. Socio-Demographic Influence

Socio-demographic factors, including age, gender, and socio-economic status, significantly influence the psychological outcomes of glaucoma patients [55,56]. For instance, studies suggest that women with depression are more likely to develop primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG), potentially due to underlying biological or psychosocial vulnerabilities [30,54]. Interestingly, living in neighborhoods with higher socio-economic status was associated with an increased risk of POAG, potentially due to greater access to healthcare and higher rates of diagnosis. These findings underscore the complexity of socio-demographic influences and highlight the need for targeted interventions addressing the specific needs of different population groups [57]. The prolonged disease trajectory can additionally lead to feelings of hopelessness and frustration, further exacerbating the mental health burden [3,27]. Rezapour et al. (2018) [21] discovered that there was no notable correlation between self-reported glaucoma and depression or anxiety, even after accounting for age and gender. This inconsistency across studies suggests that socio-demographic factors might interact in complex ways with mental health outcomes, necessitating further research to uncover the underlying mechanisms. Our results highlight how geographic, cultural, clinical, and socioeconomic factors influence the prevalence and impact of psychiatric comorbidities in glaucoma patients across Africa, Asia, Europe, and North America, including those from underrepresented regions or with unique socio-demographic contexts not covered by Ramesh et al. or Klugah-Brown et al. By identifying notable trends and discrepancies in the prevalence and impact of psychiatric disorders, these insights underscore the importance of context-specific interventions, such as tailored mental health care models and culturally sensitive education campaigns.

4.7. Assessment Tools and Methodologies

The studies reviewed employed diverse methodologies and standardized assessment tools, such as the HADS [39], BDI [40], GAD-7 [41], and PSQI [42]. The use of validated tools ensured reliable data and facilitated cross-study comparisons, enhancing the generalizability of findings. In addition, a wide range of study methodologies were employed, providing methodological diversity and a multi-perspective understanding of how glaucoma impacts mental health, drawing from both observational and experimental data.

Regarding the risk of bias, the results indicated that most studies had a low risk of bias in selection and comparability. Nonetheless, moderate to high risks were noted for some studies due to limitations in outcome ascertainment and exposure assessment. Specifically, the absence of detailed non-response information and inconsistencies in control group definitions contributed to these elevated risks.

4.8. Future Directions

Future research should focus on better understanding the link between glaucoma and psychological illnesses. Longitudinal studies are important to uncover causal relationships and to see how psychological symptoms evolve alongside the severity and treatment of glaucoma. It is also important to explore underlying factors, like the role of prolonged stress and vision loss, in contributing to mental health challenges. Research efforts should prioritize evaluating the effectiveness of psychological therapies, support groups, and patient education programs in improving mental health outcomes. Additionally, socio-demographic influences on mental health should be deeply explored to develop targeted interventions for at-risk groups. Our ambition is to expand knowledge and improve care for individuals with glaucoma by addressing both their ocular and mental health in a comprehensive, holistic way [58].

5. Conclusions

The goal of this systematic review was to examine the prevalence and types of mental illnesses in individuals diagnosed with glaucoma. The findings reveal that people with glaucoma experience significantly higher rates of psychiatric conditions, particularly depression and anxiety, compared to the general population. Sleep disturbances were also notably more common, with a clear link between the severity of glaucoma and the extent of sleep disruptions. Although less attention was given to conditions such as PTSD and psychosis, they were still reported in some cases. Socio-demographic factors, such as age, gender, and socio-economic status, were also found to influence mental health outcomes in people with glaucoma.

The chronic nature of glaucoma, along with its potential to cause irreversible vision loss, contributes to elevated levels of depression, anxiety, and other psychiatric conditions. The emotional burden of progressive vision loss can impair daily functioning and intensify feelings of isolation and helplessness in patients. The results underscore the urgent need for comprehensive care strategies and interdisciplinary collaboration to address the mental health needs of glaucoma patients. Ophthalmologists must remain vigilant for signs of depression, anxiety, and other mental health concerns in their patients. Routine mental health assessments are recommended throughout the disease course, especially during times of treatment adjustments or disease progression. The timely detection and management of mental health conditions in glaucoma patients can significantly enhance their quality of life and adherence to treatment. Developing shared care protocols and guidelines that address both vision loss and mental health is crucial for integrated care. The screen of high-risk groups should prioritize mental health assessments for advanced-stage glaucoma patients, as they are at higher risk for depression and anxiety, as well as younger patients diagnosed with glaucoma, who often exhibit heightened anxiety related to lifelong disease management, and patients experiencing sleep disturbances, which are commonly associated with advanced glaucoma. Tools such as HADS, GAD-7, and PSQI should be implemented during routine visits to identify psychiatric comorbidities early and interventions like CBT or support groups may play a key role in alleviating the psychological impact of glaucoma.

This review’s findings highlight the importance of incorporating routine screening for depression, anxiety, and other psychological disorders into standard glaucoma management. Effective collaboration among ophthalmologists, psychiatrists, and primary care providers is essential for designing comprehensive treatment plans that improve both visual and mental health outcomes.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study; The GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators. Global estimates on the number of people blind or visually impaired by glaucoma: A meta-analysis from 2000 to 2020. Eye 2024, 38, 2036–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, S.; Sangaraju, S.L.; Yepez, D.; Grandes, X.A.; Manjunatha, R.T. The nexus between diabetes and depression: A narrative review. Cureus 2022, 14, e25611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, L.S.W.; Ridge, B.; Staffieri, S.E.; Craig, J.E.; Senthil, M.P.; Souzeau, E. Quality of life in adults with childhood glaucoma: An interview study. Ophthalmol. Glaucoma 2022, 5, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, P.V.; Morya, A.K.; Azad, A.; Pannerselvam, P.; Devadas, A.K.; Gopalakrishnan, S.T.; Ramesh, S.V.; Aradhya, A.K. Navigating the intersection of psychiatry and ophthalmology: A comprehensive review of depression and anxiety management in glaucoma patients. World J. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purola, P. Social and Economic Impact of Glaucoma and Glaucoma Care in Ageing Population. Ph.D. Thesis, Tampere University, Tampere, Finland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Parravano, M.; Petri, D.; Maurutto, E.; Lucenteforte, E.; Menchini, F.; Lanzetta, P.; Varano, M.; Van Nispen, R.M.A.; Virgili, G. Association between visual impairment and depression in patients attending eye clinics: A meta-analysis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021, 139, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopilaš, V.; Kopilaš, M. Quality of life and mental health status of glaucoma patients. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1402604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman-Casey, P.A.; Niziol, L.M.; Gillespie, B.W.; Janz, N.K.; Lichter, P.R.; Musch, D.C. The Association between Medication Adherence and Visual Field Progression in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study. Ophthalmology 2020, 127, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groff, M.L.; Choi, B.; Lin, T.; Mcllraith, I.; Hutnik, C.; Malvankar-Mehta, M.S. Anxiety, depression, and sleep-related outcomes of glaucoma patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 58, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallardo, M.; Smith, O.; Trubnik, V.; Reiss, G. Interventional glaucoma and the patient perspective. Expert Rev. Ophthalmol. 2024, 19, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Sterne, J.A.C.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Egger, M. Investigating and dealing with publication bias and other reporting biases in meta-analyses of health research: A review. Res. Synth. Methods 2021, 12, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayaki, M.; Shiba, D.; Negishi, K.; Tsubota, K. Depressed visual field and mood are associated with sleep disorder in glaucoma patients. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belendiuk, K.A.; Baldini, L.L.; Bonn-Miller, M.O. Narrative review of the safety and efficacy of marijuana for the treatment of commonly state-approved medical and psychiatric disorders. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2015, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Méndez-Ulrich, J.L.; Sanz, A. Psycho-ophthalmology: Contributions of health psychology to the assessment and treatment of glaucoma. Psychol. Health 2017, 32, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, M.Z.; Rane-Malcolm, T.; Tatham, A.J.; Dhillon, B.; Cotton, A.; Shah, P.; Sanders, R. Cognitive impairment and psychiatric symptoms in normal tension glaucoma (NTG)-A naturalistic study. New Front. Ophthalmol. 2016, 2, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-Y.; Lin, C.-L.; Lai, S.-W.; Kao, C.-H. Association of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use and acute angle-closure glaucoma. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2016, 77, 19941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulut, M.; Yaman, A.; Erol, M.K.; Kurtuluş, F.; Toslak, D.; Coban, D.T.; Başar, E.K. Cognitive performance of primary open-angle glaucoma and normal-tension glaucoma patients. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2016, 79, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, V.C.-H.; Ng, M.-H.; Chiu, W.-C.; McIntyre, R.S.; Lee, Y.; Lin, T.-Y.; Weng, J.-C.; Chen, P.-C.; Hsu, C.-Y. Effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on glaucoma: A nationwide population-based study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ra, S.; Ayaki, M.; Yuki, K.; Tsubota, K.; Negishi, K. Dry eye, sleep quality, and mood status in glaucoma patients receiving prostaglandin monotherapy were comparable with those in non-glaucoma subjects. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-Y.; Lai, Y.-J.; Wang, J.-P.; Shen, Y.-C.; Wang, C.-Y.; Chen, H.-H.; Hu, H.-Y.; Chou, P. The association between glaucoma and risk of depression: A nationwide population-based cohort study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018, 18, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezapour, J.; Nickels, S.; Schuster, A.K.; Michal, M.; Münzel, T.; Wild, P.S.; Schmidtmann, I.; Lackner, K.; Schulz, A.; Pfeiffer, N. Prevalence of depression and anxiety among participants with glaucoma in a population-based cohort study: The Gutenberg Health Study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018, 18, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringham, J.; Ashkenazy, N.; Galor, A.; Wellik, S.R. Barriers to glaucoma medication compliance among veterans: Dry eye symptoms and anxiety disorders. Eye Contact Lens 2018, 44, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.-H.; Kang, E.Y.-C.; Lin, Y.-H.; Wu, W.-C.; Liu, Z.-H.; Kuo, C.-F.; Lai, C.-C.; Hwang, Y.-S. Association of ocular diseases with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder: A retrospective case-control, population-based study. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilahun, M.M.; Yibekal, B.T.; Kerebih, H.; Ayele, F.A. Prevalence of common mental disorders and associated factors among adults with Glaucoma attending University of Gondar comprehensive specialized hospital tertiary eye care and training center, Northwest, Ethiopia 2020. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Han, K.; Wang, S.; Yoon, H.Y.; Moon, J. Il Effect of depressive symptom and depressive disorder on glaucoma incidence in elderly. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5888. [Google Scholar]

- Berchuck, S.; Jammal, A.; Mukherjee, S.; Somers, T.; Medeiros, F.A. Impact of anxiety and depression on progression to glaucoma among glaucoma suspects. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 105, 1244–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, D.Y.; Jung, K.I.; Park, H.Y.L.; Park, C.K. The effect of anxiety and depression on progression of glaucoma. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, J.D.; Khawaja, A.P.; Weizer, J.S. Glaucoma in adults—Screening, diagnosis, and management: A review. JAMA 2021, 325, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subhi, Y.; Schmidt, D.C.; Bach-Holm, D.; Kolko, M.; Singh, A. Prevalence of Charles Bonnet syndrome in patients with glaucoma: A systematic review with meta-analyses. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021, 99, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wändell, P.E.; Ljunggren, G.; Wahlström, L.; Carlsson, A.C. Psychiatric diseases and dementia and their association with open-angle glaucoma in the total population of Stockholm. Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 3348–3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Kong, X.; Sun, X. Anxiety and depression in Chinese patients with glaucoma and its correlations with vision-related quality of life and visual function indices: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e046194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayal, A.; Sodimalla, K.V.K.; Chelerkar, V.; Deshpande, M. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with primary glaucoma in Western India. J. Glaucoma 2022, 31, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klugah-Brown, B.; Bore, M.C.; Liu, X.; Gan, X.; Biswal, B.B.; Kendrick, K.M.; Chang, D.; Zhou, B.; Becker, B. The neurostructural consequences of glaucoma and their overlap with disorders exhibiting emotional dysregulations: A voxel-based meta-analysis and tripartite system model. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 358, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Villanueva, C.; Milla, E.; Bolarin, J.M.; García-Medina, J.J.; Cruz-Espinosa, J.; Benítez-del-Castillo, J.; Salgado-Borges, J.; Hernández-Martínez, F.J.; Bendala-Tufanisco, E.; Andrés-Blasco, I. Impact of systemic comorbidities on ocular hypertension and open-angle glaucoma, in a population from Spain and Portugal. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulhaq, Z.S.; Soraya, G.V.; Dewi, N.A.; Wulandari, L.R. The prevalence of anxiety symptoms and disorders among ophthalmic disease patients. Ther. Adv. Ophthalmol. 2022, 14, 25158414221090100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, J.L.; Feehan, M.; Tak, C.; Owen, L.A.; Finley, R.C.; Cromwell, P.A.; Lillvis, J.H.; Hicks, P.M.; Au, E.; Farkas, M.H. Heritable risk and protective genetic components of glaucoma medication non-adherence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Fu, L.; Feng, F.; Liu, B.; Lei, Y.; Kang, Q. Mendelian randomization study shows no causal relationship between psychiatric disorders and glaucoma in European and East Asian populations. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1349860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Lv, X.; Wu, G.; Zhou, X.; Tian, H.; Qu, X.; Sun, H.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C. Glaucoma is not associated with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 688551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, M.A.; Muzzatti, B.; Bidoli, E.; Flaiban, C.; Bomben, F.; Piccinin, M.; Gipponi, K.M.; Mariutti, G.; Busato, S.; Mella, S. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) accuracy in cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 3921–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.; Park, J. Diagnostic test accuracy of the beck depression inventory for detecting major depression in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2022, 31, 1481–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Wang, X.; Shen, B.; Xian, J.; Ding, Y. Validation of the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7) as a screening tool for anxiety among pregnant Chinese women. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zitser, J.; Allen, I.E.; Falgàs, N.; Le, M.M.; Neylan, T.C.; Kramer, J.H.; Walsh, C.M. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) responses are modulated by total sleep time and wake after sleep onset in healthy older adults. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allison, K.; Patel, D.; Besharim, C. The value of annual glaucoma screening for high-risk adults ages 60 to 80. Cureus 2021, 13, e18710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, R.; Li, V.S.W.; Wong, M.O.M.; Chan, P.P.M. Pediatric Glaucoma-From Screening, Early Detection to Management. Children 2023, 10, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabel, B.A.; Wang, J.; Cárdenas-Morales, L.; Faiq, M.; Heim, C. Mental stress as consequence and cause of vision loss: The dawn of psychosomatic ophthalmology for preventive and personalized medicine. EPMA J. 2018, 9, 133–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillmann, K.; Hoskens, K.; Mansouri, K. Acute emotional stress as a trigger for intraocular pressure elevation in Glaucoma. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019, 19, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.T.J.; Bahajjaj, S.I.B.Z.-A.; Lateef, F.; Helen, Z.Y. Drug-Induced Acute Angle-Closure Glaucoma-Raising your Index of Suspicion. Biomed. J. Sci. Tech. Res. 2021, 36, 28689–28696. [Google Scholar]

- Ciobanu, A.M.; Dionisie, V.; Neagu, C.; Bolog, O.M.; Riga, S.; Popa-Velea, O. Psychopharmacological Treatment, Intraocular Pressure and the Risk of Glaucoma: A Review of Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dołoto, A.; Bąk, E.; Batóg, G.; Piątkowska-Chmiel, I.; Herbet, M. Interactions of antidepressants with concomitant medications-safety of complex therapies in multimorbidities. Pharmacol. Rep. 2024, 76, 714–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Sun, X. Etiologies and clinical characteristics of young patients with angle-closure glaucoma: A 15-year single-center retrospective study. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2021, 259, 2379–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antos, Z.; Zackiewicz, K.; Tomaszek, N.; Modzelewski, S.; Waszkiewicz, N. Beyond Pharmacology: A Narrative Review of Alternative Therapies for Anxiety Disorders. Diseases 2024, 12, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rák, T.; Csutak, A. Complementary Practices in Pharmacy and Their Relation to Glaucoma—Classification, Definitions, and Limitations. Sci. Pharm. 2024, 92, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, J.E.; Kleiman, M.J.; Walker, M. Using Optical Coherence Tomography to Screen for Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 2021, 84, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tharmathurai, S.; Huwaina, A.S.; Azhany, Y.; Razak, A.A.; Che-Hamzah, J.; Fazilawati, Q.; Tajudin, L.-S.A. Quality of Life of Older Adults with Primary Open Angle Glaucoma using Bahasa Malaysia Version of Glaucoma Quality of Life 36 Questionnaire. Curr. Aging Sci. 2022, 15, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delavar, A.; Bu, J.J.; Radha Saseendrakumar, B.; Weinreb, R.N.; Baxter, S.L. Gender Disparities in Depression, Stress, and Social Support Among Glaucoma Patients. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2023, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDermott, C.E.; Salowe, R.J.; Di Rosa, I.; O’Brien, J.M. Stress, Allostatic Load, and Neuroinflammation: Implications for Racial and Socioeconomic Health Disparities in Glaucoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajith, B.S.; Najeeb, N.; John, A.; Anima, V.N. Cross sectional study of depression, anxiety and quality of life in glaucoma patients at a tertiary centre in North Kerala. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 70, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaštelan, S.; Pjevač, N.; Braš, M.; Đorđević, V.; Keleminić, N.P.; Mezzich, J.E. A person-centered approach in ophthalmology: Optimizing glaucoma care. Int. J. Pers. Cent. Med. 2023, 13, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).