Abstract

Antioxidants are compounds that prevent or delay the oxidation process, acting at a much smaller concentration, in comparison to that of the preserved substrate. Primary antioxidants act as scavenging or chain breaking antioxidants, delaying initiation or interrupting propagation step. Secondary antioxidants quench singlet oxygen, decompose peroxides in non-radical species, chelate prooxidative metal ions, inhibit oxidative enzymes. Based on antioxidants’ reactivity, four lines of defense have been described: Preventative antioxidants, radical scavengers, repair antioxidants, and antioxidants relying on adaptation mechanisms. Carbon-based electrodes are largely employed in electroanalysis given their special features, that encompass large surface area, high electroconductivity, chemical stability, nanostructuring possibilities, facility of manufacturing at low cost, and easiness of surface modification. Largely employed methods encompass voltammetry, amperometry, biamperometry and potentiometry. Determination of key endogenous and exogenous individual antioxidants, as well as of antioxidant activity and its main contributors relied on unmodified or modified carbon electrodes, whose analytical parameters are detailed. Recent advances based on modifications with carbon-nanotubes or the use of hybrid nanocomposite materials are described. Large effective surface area, increased mass transport, electrocatalytical effects, improved sensitivity, and low detection limits in the nanomolar range were reported, with applications validated in complex media such as foodstuffs and biological samples.

1. Antioxidants—General Aspects and Main Determination Techniques

1.1. Defining, Classifying and Describing Modes of Action Antioxidants

Antioxidants are chemical species that prevent or delay oxidation processes. They originate from various sources and hamper lipid peroxidation following different mechanisms of intervention, acting at a much smaller concentration, in comparison to that of the preserved compound [1,2,3,4,5].

Primary antioxidants act as scavenging or chain breaking antioxidants, delaying initiation or disrupting propagation. Secondary antioxidants quench singlet oxygen, decompose peroxides in non-radical species, chelate prooxidative metal ions, inhibit oxidative enzymes or absorb UV radiation. It has been confirmed that they can exploit the above-described mechanisms to stabilize/regenerate primary antioxidants [1].

Considering antioxidants’ reactivity, four lines of defense have been described. Antioxidants belonging to the first line of defense withhold radical species generation. The second line of defense includes mainly radical scavenging antioxidants. The third line of defense intervenes after the free radical-caused insults, being composed of repair antioxidants. Adaptation mechanisms underlie the mode of action of the fourth line of defense: Signals required for free radical generation are exploited, thus such antioxidants can disrupt free radical occurrence or reactions implying radical species intervention [6,7].

Superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase, metal-binding proteins like lactoferrin, ferritin, caeruloplasmin, glutathione, uric acid, alpha-lipoic acid, ubiquinones, bilirubin, and melatonin are well-recognized endogenous antioxidants. Tocopherols, phenolics, vitamin C, and carotenoids are exogenous antioxidants found in food and /or dietary supplements, slowing up the use of endogenous antioxidants, so the cell’s own antioxidant profile can remain unaltered [1,8].

Synthetic antioxidants such gallic acid esters, synergistic butylated hydroxyanisole and butylated hydroxytoluene are added to foodstuffs to prevent rancidity. Another antioxidant classification takes account on the solubility: Hydrophilic (ascorbic acid, glutathione, uric acid, flavonoids) and lipophilic (carotenoids, tocopherols, ascorbyl palmitate, or stearate) antioxidants [1].

With respect to the mechanism involved in free radical inactivation, antioxidant can follow either hydrogen atom transfer, or single electron transfer. Hydrogen atom transfer is swift and is not dependent on pH or nature of solvent, but proved sensitive to the presence of other reductant species. The behavior of an antioxidant molecule can also encompass single electron transfer [9,10]. Considering the analytical methods developed, hydrogen atom transfer underlies Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC), Total Radical Trapping Antioxidant Potential (TRAP) and chemiluminescence, whereas single electron transfer underlies Ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP), and Cupric Reducing Antioxidant Capacity (CUPRAC) [2,10]. 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity (TEAC) can exploit both mechanisms [10,11].

Antioxidants can hamper the deleterious effects of free radicals in the human body, as well as the oxidative decay of food components [1,2,3,12,13,14]. Although both terms have been employed in papers approaching antioxidant assay, distinction has been drawn between antioxidant activity and antioxidant capacity. The antioxidant capacity reflects the conversion of the reactive oxygenated species that is scavenged. This illustrates the scavenging ability, and can be expressed as the amount, as moles, of the scavenged free radical by antioxidants [15,16], present in an analyzed sample, for instance a plant extract [17]. The term “antioxidant activity” is prevalent in electrochemical approaches, that directly provide informations about analyte concentration. Hence, “antioxidant activity” is linked to a thermodynamic significance, as it can be correlated to the total active or effective concentration of antioxidants, or oxidants in a sample. It can be expressed as units of standard antioxidant, for instance milligrams, mmoles or μmoles Trolox equivalents or other reference antioxidant (ascorbic acid, gallic acid, quercetin, catechin, rutin), per amount (grams, kilograms, liters, etc.) of sample. “Antioxidant power” and “antioxidant ability” are less used, and they do not have a precise interpretation [18].

1.2. Analytical Methods Applied to Antioxidant Determination

1.2.1. General Overview of Methods

Antioxidant assay can rely on a plethora of methods, based on electrochemical, spectrometrical or chromatographic detection [4,19,20]. A synoptic overview of the principles underlying the main analytical techniques and detection systems applied to antioxidant assay is presented in Table 1 [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62].

Table 1.

The main analytical methods applied to antioxidant assay [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62].

The advantages and shortcomings of the methods applied in antioxidant assay have been described by Sadeer et al. [20]. Photometric techniques such as DPPH, ABTS are rapid, simple, and provide reproducible results, whereas TBARS assay is characterized by not so good sensibility and specificity [20]. Chromatographic techniques offer accurate and reproducible results, but are often laborious, time-consuming, and require specialized equipment and skilled personnel. Electroanalytical techniques benefit from the rapidity and sensitivity of the electrochemical detection, with specificity improvable by the use of mediators and enzymes in modified electrodes.

1.2.2. Electrochemical Techniques

This sub-section provides a characterization of electroanalytical techniques applied to individual antioxidant content and antioxidant activity determination. Voltammetric and amperometric/biamperometric methods are the most broadly used.

These techniques are able to provide direct assay of the total antioxidant activity, even in the absence of reactive species. Voltammetric and amperometric techniques, including integration in flow injection analysis set-up and microfluidic chip configurations coupled with amperometric detection, relate oxidation potential to antioxidant activity [63,64]. Developing enzyme electrodes by biocatalyst incorporation enables viable assay of the total antioxidant profile or total phenolics, with quantitation in food and beverages, biological samples, pharmaceuticals [63].

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) as potentiodynamic technique involves linear variation applied to the working electrode’s potential, in a triangular waveform, and the recording of the current intensity. The anodic oxidation and cathodic reduction potentials (Ea and Ec) furnish qualitative informations, whereas the intensities of the anodic and cathodic peaks (Ia, Ic) are related the analyte’s amount. For reversible systems, the values of the intensities of the cathodic and anodic peaks are equal. For irreversible systems, the presence of one peak can be noticed on the voltammogram. Cyclic voltammetry has proved its analytical viability for the quantitation of low molecular weight antioxidant capacity of plant extracts, tissue homogenates and blood plasma. The oxidation potential and half-wave potential are linked to the nature of the antioxidant analyte(s); the intensity of the current measured for the anodic peak and the area of the anodic wave underlie quantitative assay [45].

Differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) implies one measurement before applying the potential pulse, and a second towards the end of the pulse period. Sampling the current just before the potential is changed, lowers the effect of the charging current and enhances faradaic current. In differential techniques, the advantage consists in measuring the Δi/ΔE value, where Δi is the difference between the current intensity values, taken just before pulse application, and at the end of the pulse period. Another consequence of double intensity measurement is the presence of the analytical signals in the form of sharp peaks, with improved resolution and sensitivity [53].

Square-wave voltammetry (SWV): A square-wave is superimposed on the potential staircase variation, whereas the current is recorded at the end of each potential change, minimizing charging current, just as in differential pulse technique. Square-wave voltammetry facilitates data acquisition with high sensitivity and minimization of background signals. The fast potential scan enables repetitive measurements, with signals acquired at optimized signal-to-noise ratio. The technique benefits from high contribution of the faradaic current, increased resolution and sensitivity [53].

Staircase voltammetry is a derivative of the linear scan technique less applied in antioxidant assay, for which the potential sweep is a succession of stair steps. The current intensity is measured at the end of each potential change, just before the following step, so contribution of capacitive current is lowered.

Chronoamperometry relies on applying single or double potential steps, and the current resulting from faradaic processes that occur at the electrode is measured as a function of time. As in the case of other pulsed techniques, generated charging currents exponentially decline with time. The Faradaic current due to electron transfer diminishes as revealed by Cottrell equation, that illustrates the inverse dependence of the recorded intensity response, on the square root of time (seconds), under diffusion-controlled conditions. By integrating current intensity over longer periods of time, chronoamperometry improves signal to noise ratio versus other amperometric methods.

Chronocoulometry relies on analogous principles, but it records the variation of charge with time, instead of the current–time dependence. Nevertheless, in chronocoulometry, a signal increase in time is monitored instead of a decrease; signal integration diminishes noise, resulting in a smooth hyperbolic curve; the contributions of absorbed or double-layer charging species become readily noticeable.

Polarography: Polarography is a particular variant of linear sweep voltammetry, that makes use of mercury drop electrode [52]. As a technique with linear potential scan, it is controlled by mass transport, and the recorded polarograms (the current versus potential dependences) have a characteristic sigmoidal shape. The current oscillations noticed on the polarogram are assigned to the mercury drops that fall from the capillary. The limiting current is a diffusion one, as diffusion is the main contributor to the flux of electroactive compounds towards the electrode. The method may suffer from a significant capacitive current contribution, due to the continuous current measurement. Recently, a Clark’s standard Pt electrode was employed for antioxidant activity assay, relying of the measurement of the rate of oxygen intake of a microsomal suspension [51].

The amperometric method: Amperometry involves the measurement of the intensity of the current generated by the oxidation/reduction of an electroactive analyte. During this type of electrochemical assay, the value of the potential is maintained at a fixed value with respect to a reference electrode [65]. The current measured at constant potential due to the oxidation/reduction of the electroactive analyte can be directly correlated to the concentration of the latter. The performances of this technique depend on the working potential. Lowering of the latter, with improvable sensitivity and selectivity, is possible by the use of mediators or enzyme incorporation [53].

The biamperometric method: Biamperometry relies on the measurement of the current flowing between two identical working electrodes, at a small potential difference. Biamperometric selectivity is dependent on the specificity of the reaction between the analyte and the oxidized/reduced form of the redox pair and the analyte. A redox pair largely used in biamperometric studies is DPPH•/DPPH. The recorded analytical signal is proportional to the residual concentration of DPPH•, after its reaction with the antioxidant. Other redox couples used in biamperometric antioxidant capacity assay are ABTS+∙/ABTS, Fe3+/Fe2+, Fe(CN)63−/Fe(CN)64−, Ce4+/Ce3+, VO3−/VO2+, and I2/I− [56,66,67]. The assay of total antioxidant capacity has been applied to the analysis of alcoholic beverages [56] and juices [68].

Potentiometry: Potentiometric measurements logarithmically correlate the electrochemical cell’s potential to the analyte concentration. Lowered potentials signify enhanced electron-donating abilities and, consequently, increased antioxidant potentials. Potentiometry does not need current or potential modulation as in voltammetry/amperometry [53]. It relies on the potential variation that results from a change in the ratio oxidized form/reduced form of an indicating redox species. With the increase of the antioxidant level, the concentration of the reduced form of the indicator increases, and the subsequent potential change is recorded [69]. Possible drawbacks in ion selective potentiometry can encompass deviations from Nernst’s equation, caused by changes in ion activity or temperature.

1.2.3. Biosensor Methods

Biosensors have been applied to the assay of compounds endowed with reductive/antioxidant properties [70,71]. Oxido-reductases are often encountered in biosensor applications, due to the confirmed enhanced electron transfer ability. Biocatalysts act at low concentrations when compared to those of the target analytes (substrates) and do not always require the presence of cofactors. Laser-derived graphene sensors based on nanomaterials and conducting polymers were applied in environmental monitoring, food safety assay, and clinical diagnosis [72]. The use of multienzyme systems in electrochemical biosensors enables detection of a broad spectrum of compounds, as well as the improvement of electrochemical biosensor’s analytical parameters, selectivity and sensitivity [73].

A series of review papers and books refer to antioxidant and antioxidant capacity assay by the use of biosensors [74,75,76,77,78,79]. Applications of biosensors for assessing antioxidant potential are based on monitoring superoxide anion radical (O2•−), nitric oxide (NO), glutathione, uric acid, phenolics, or ascorbic acid [80]. A carbon paste biosensor developed by DNA incorporation relied on the partial damage of the DNA layer present on the electrode surface by OH• radicals, produced in a Fenton system. The electro-oxidation of the intact-remaining adenine nucleobases, generated an oxidation product able to catalyse NADH oxidation. Sample antioxidants scavenged OH•, so more adenine molecules were left unoxidized, resulting in an increase of the catalytic current given by NADH oxidation, quantified in differential pulse voltammetry. Ascorbic acid served as model antioxidant, enabling quantitation of levels as low as 50 nM ascorbic acid in aqueous media [81].

Amperometric biosensors applied in the assessment of phenolics, major contributors to the antioxidant capacity of plants, incorporated laccase, tyrosinase, or peroxidase [82,83,84,85]. Phenolic compounds could be quantitated by enzyme sensors developed by immobilizing polyphenol oxidase (PPO) into conducting copolymers obtained by co-electropolymerization of pyrrole with thiophene-capped polytetrahydrofuran [84]. Phenolic compounds are also determined using biosensors based on oxidases such as tyrosinase and laccase [86].

The principles of developing and particular applications of carbon-based sensors will be discussed in the next sections, given the increasing need for high performance analytical tools in the field of antioxidant assay, linked to food quality and health status monitoring.

2. Carbon Electrodes—General Overview

Carbon electrodes are largely employed in electroanalysis due to their special features, that encompass large surface area, tunable porosity, high electroconductivity, chemical stability, temperature resistance, nanostructuring possibilities, facility of manufacturing at low cost, and easiness of surface modification. The carbonaceous electrodes were classified as carbon paste, glassy carbon, fullerenes, graphite, diamond, and screen- printed electrodes [87].

Carbon Paste Electrodes: Carbon paste electrodes are synthesized from graphite powder and various water-immiscible nonelectrolytic organic pasting liquids, such as mineral (paraffin) oil, [88,89]. Most often high purity mineral oil (Nujol) is employed, nevertheless quasi-solid binders such as silicone grease or polypropylene could replace commonly used pasting liquids, but the developed structure has much higher density and becomes less easy to handle [90]. The advantages of carbon paste electrodes are facility of including modifiers (for developing novel, redox-mediated sensors), very low ohmic resistance, minimized toxicity of this environmentally compatible material, reduced background current, individual polarizability [87]. Obtaining carbon paste electrodes can also be rely on alternative carbon-based materials, replacing graphite powder with glassy carbon powder, carbon nanotubes, porous carbon foam, acetylene black [90].

Glassy Carbon Electrodes: Glassy carbon, also called vitreous carbon is a type of nongraphitizing, solid, three-dimensional carbon material, broadly used in electro-assay. It is obtained at temperatures above 2000 °C, to decompose pyrolysis intermediates that generally exhibit a scarce thermal conductivity [91]. The surface of glassy carbon electrodes can be modified with functional nanomaterials (metals, alloys, or metal oxides) [92,93]. Glassy carbon and glassy carbon-based electrodes provide excellent electroconductivity, mechanical resistance, broad potential range, and gas impermeability [87]. They have large potential window and chemical stability, prove better resistance to solvents than metal electrodes, been confirmed for their viability at the assay of organic compounds. Bare glassy carbon electrodes are characterized by facility of use, being mechanically cleaned by mere polishing on alumina slurry, procedure that can be followed by sonication in aqueous medium. Nevertheless, residual alumina particles on the electrode surface can affect the recorded electrochemical profile of electroactive analytes endowed with reductive (antioxidant) potential, such as phenolics [94].

Glassy carbon modification with alumina particles aimed at improving sensitivity in the case of dopamine [95]. The application of alumina-modified glassy carbon electrode promotes sensitivity, detectability and selectivity in the case of nitroaromatic compounds. Enhancement of dissolved oxygen electrochemical reduction in the presence of alumina was also reported [96]. Employing alumina suspensions for modifying glassy carbon electrodes by abrasive polishing, resulted in successful electro-assay of various phenolics. Modification of glassy carbon electrodes with α-alumina resulted in improved electrochemical response in comparison with θ and γ–alumina, and it was confirmed that alumina structure, and not the particle size or surface area, can exert notable effects [97].

Glassy carbon modification with alumina enhanced the voltammetric current response of gallic acid, caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, catechin, quecetin, and rutin. By applying this simple procedure of electrode modification, lowered DPV relative standard deviation (RSD < 3%, n = 5) for repetitive assays and high inter-electrode precision (RSD < 4%, n = 3) were reported. Nevertheless, when use of unmodified glassy carbon electrodes is chosen, the application of the sonication step to remove all residual alumina is compulsory, as alumina remaining on the electrode surface can significantly affect the voltammetric profile of sample antioxidants [98].

The use of other metal oxides for modification, may also provide performance improvement in the electrochemical determination of antioxidant species. Modification with metal (gold, silver and platinum) or metal oxide nanoparticles imparts distinctive size-dependent electrochemical features. The sol-gel chemistry served for developing silica-modified electrodes, exploiting silica adsorption properties [98,99].

Carbon nanomaterials were divided into: Zero-dimensional fullerenes [100], one dimensional carbon nanotubes [101], two-dimensional graphene [102], and the three-dimensional porous carbons [103]. Porous carbon materials are fabricated using precursors named template composite materials which are synthesized, with subsequent carbonization and template removal [104]. Nevertheless, such a technique is laborious and necessitates a series of synthetic steps, the first stage of template injection, the etching process and the long solidification time [105], which may restrict mass applications of porous carbon materials [106].

Fullerene Electrodes: Fullerenes represent a class of carbon compounds in which carbon atoms form closed cage or cylinder-shaped structures. In the first case the compound is called Buckminsterfullerene (C60, named after the American architect R. Buckminster Fuller, whose geodesic dome was constructed relying on the same structural principles), and in the second case, the obtained structure is called carbon-nanotube [107,108,109]. Single-walled and multi-walled carbon nanotubes are widely employed in electrode modification, being biocompatible, having large surface area to volume ratio, enhanced electro-conductivity, chemical and mechanical resistance.

In the structure of graphene, atoms constitute a single layer and are placed in a two-dimensional honeycomb lattice. Each atom uses sp2 hybridized orbitals to connect by sigma bonds to its three nearest neighbors, and contributes with one electron (belonging to the p unhybridized orbital) to the conduction band that is common for the whole sheet. This type of bond is also encountered in carbon nanotubes, fullerenes and glassy carbon. Graphene oxide nanoparticles, alongside metal oxide nanoparticles are largely used in electrode modification, aiming at antioxidant determination. The oxygenated groups can lead to improvement in the electrochemical responses and mechanical properties. The polarity of these groups present at the surface of graphene oxide results in high dispersibility in polar solvents, enabling applications in biosensing systems.

Graphite Electrodes: Graphite is an allotropic form of carbon, where sp2-hybridized atoms form planes of hexagonal bonds. Graphite is a stable crystalline form of carbon, which can be employed as such, or in the form of composites [110,111,112,113]. Electrodes are inexpensive, commercially available and easy to modify, so they benefit from selectivity enhancement through various modifications, renewable surfaces and hazard-free polishing [114]. The high delocalization degree of pi electrons and the weak van der Waals interactions between the layers, result in good electro-conductivity.

Diamond Electrodes: Diamond is an allotrope form of carbon with insulating properties, very good mechanical resistance, the hardness being due to the bonds established between sp3 carbon atoms. Diamond is a non-easily accessible material, whose preparation require high temperatures and pressures [115]. By doping diamond with boron in different proportions, conductive, superconducting or semiconductor materials can be synthesized. These electrodes are chemically inert and are endowed with excellent electrical features. High boron-doped (103–104 ppm) diamond has metal-like conductivity and can be applied as electrode material [116]. Boron-doped polycrystalline diamond exhibits a rougher morphology, a higher sp3 content, a broader water potential window, and a lower background current [117].

Screen-Printed Electrodes: Such electrodes are developed by printing inks on ceramic or plastic surfaces. The inks, depending on the composition (carbon, gold, platinum) will determine the characteristics of screen-printed electrodes, that can be part of a three electrode set-up in a measuring cell. Depending on the target analyte, the ink can be modified by incorporation of metal powders, redox complexes or biocatalysts, to promote electron transfer [118,119,120].

Glassy carbon, vitreous carbon, carbon nanotubes, fullerenes, screen-printed, graphite, and diamond electrodes are considered homogenous carbon electrodes, whereas carbon paste and modified carbon pastes are heterogeneous carbon electrodes.

In a recent study, a detailed description of advantages and shortcomings of several broadly employed types of carbon-based electrodes is provided [121].

Carbon paste electrodes offer an analytical response on wide potential ranges, with small background current, reduced ohmic resistance, and facility of tuning pretreatment methods and surface modification. These materials do not harm the environment and operate at low cost. Nevertheless, they were characterized as not stable for functioning in flow systems, are not compatible with organic solvents, and often require recalibration. When using organic compounds as binders, the use of such sensors results in irreversibility of recorded voltammograms, and the surface roughness can influence reproducibility of the response.

Glassy carbon electrodes exhibit high mechanical resistance and excellent electro-conductivity. They are characterized by chemical inertness and function on large potential domains, over wide pH ranges, from strongly acidic to alkaline environment. Their large size and difficulty to manufacture at large scale may constitute inconvenients. The electron transfer occurs slower than at electrodes based on noble metals.

Carbon fiber microdisk electrodes are easy to use due to their small diameter and benefit from high speed of electron transfer. They give a rapid analytical response and exhibit high sensitivity for small concentration changes. Being compatible with biological media and non-toxic to cells, can be applied successfully to in vivo determinations. Nevertheless, they may not exhibit resistance to the mechanical force or to the high temperatures applied during the step of capillary pulling. Low selectivity and the possibility to break glass insulation during in vivo measurements are other disadvantages.

Basal plane pyrolytic graphite electrodes are characterized by high speed electrode reaction kinetics, with lowered background signal. Shortcomings may be the irreversible behavior and the large dimensions.

Screen-printed carbon electrodes are easy to employ, due to portability and facility to apply modifications. A broad series of geometries can be obtained, and the determinations can be performed with the possibility to eliminate surface fouling, and low cost. Nevertheless, the incorporated binders may alter the shape of voltammograms. Fouling of the electrode surface may be caused by products of redox reactions. Other shortcomings may be the rough surface and the slow reaction kinetics. The organic solvents present in the buffer may dissolve the ink, diminishing sensitivity.

Given the confirmed advantages of boron-doped diamond (excellent electroconductivity, mechanical resistance), the behavior of this type of electrode has been investigated in cyclic voltammetry of gallic acid. At low potentials, when the electrolytes are stable, deactivation of boron-doped diamond has been reported. It was found that gallic acid electro-oxidation generated the occurrence of a polymeric film on the anodic surface, causing boron-doped diamond deactivation [122].

3. Determination of Individual Antioxidants with Carbon-Based Electrodes

The determination of individual key antioxidants relied on a series of unmodified or modified carbon-based electrodes. An overview of the analytical parameters and applications on real samples, at the assay of some individual antioxidants, using carbonaceous working electrodes is presented in Table 2 [123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167].

Table 2.

Electroanalytical techniques applied to the assay of key individual antioxidants [123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167].

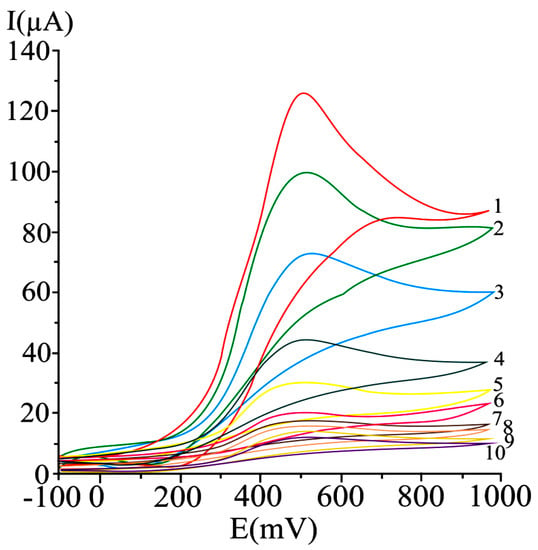

A series of irreversible cyclic voltammograms recorded for increasing ascorbic acid concentrations, at a carbon paste electrode are given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Cyclic voltammograms obtained at a carbon paste working electrode at varying ascorbic acid concentrations, as mM: 20 (1), 15 (2), 10 (3), 5 (4), 2.5 (5), 1.25 (6), 0.625 (7), 0.31 (8), 0.15 (9), and 0.07 (10); potential scan rate 50 mV/s [123].

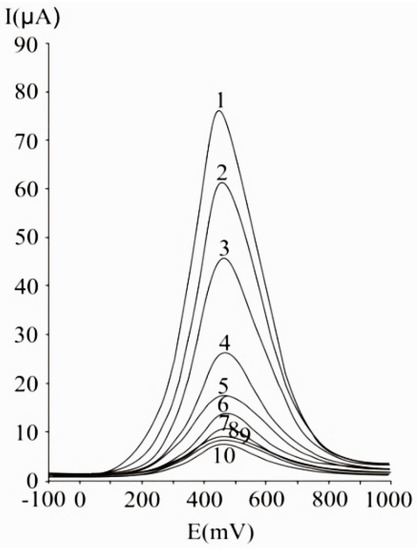

A 50 mV s−1 cyclic voltammetric scan rate could enable analyte diffusion to the electrode and promoted electron transfer. In the case of irreversible or quasi-reversible voltammograms [123,168], at elevated scan rates, electron transfer is slow relative to the applied potential sweep rate, so the rate of establishing the equilibrium at the electrode is diminished. In the case of very elevated scan rates, peaks have high current intensities, but distortions may occur on the voltammogram [168]. In differential pulse voltammetry at carbon paste electrode (Figure 2), the optimum value of 75 mV was used for the pulse amplitude, and 125 ms was chosen for the pulse period, allowing a good compromise between promoting analytical signal, minimizing noise and good resolution [123].

Figure 2.

Differential pulse voltammograms obtained with a carbon paste working electrode for different ascorbic acid concentrations, expressed as mM: 20 (1), 15 (2), 10 (3), 5 (4), 2.5 (5), 1.25 (6), 0.625 (7), 0.31 (8), 0.15 (9), and 0.07 (10); experimental conditions: Pulse amplitude 75 mV, pulse period 125 ms, potential scan rate 50 mV/s [123].

4. Determination of Total Antioxidant Activity with Carbon-Based Electrodes

Bare and modified carbon-based electrodes have been used for the antioxidant activity and its main contributors’ assessment. The electrochemical measurements are performed as per reference to a standard antioxidant, Trolox, gallic acid, ascorbic acid or quercetin, etc. In most of the cases, the peak intensities or peak areas are considered, providing quantitative informations.

Often, authors report indexes illustrating antioxidant activity: IC30 and IC50 [169]. IC50 corresponds to the antioxidant amount that induces a change of a model signal by 50%. The lower the concentration required for 50% increase or inhibition of the considered model signal, the more active the antioxidant. Korotkova et al. [170] relied on the modifications in the oxygen electro-reduction current in the presence of antioxidants, as criteria to determine IC50 by voltammetry. Catalase and superoxide dismutase yielded an increase of the oxygen electro-reduction current, when compared to the signal obtained in supported electrolyte. Superoxide dismutase presented an IC50 value of 1.08 μM [170]. Wei et al. evaluated IC50, as the antioxidant amount that diminishes the oxidation peak of superoxide by 50%. They reported an IC50 value of ascorbic acid of 5 × 10–4 mol/L [171].

Blasco et al. [172] define the “Electrochemical Index” as the total polyphenolic content measured by an electrochemical technique. In this approach, the corresponding total phenolics concentration obtained from the “total electrochemical signal” was named “Electrochemical Index”. The total electrochemical signal was assimilated to the total amperometric current measured at controlled potential (800 mV), to achieve oxidation of all polyphenolics at neutral pH of 7.5. So, the “Electrochemical Index” became an approach to “total polyphenols” in samples without ascorbic acid (or alpha-tocopherol), or an approach to “total natural antioxidant” content in those samples where ascorbic acid (or alpha-tocopherol) could be present [172].

An overview of the analytical parameters and real sample applications regarding the assay of total antioxidant activity by the use of carbon-based working electrodes is given in Table 3 [173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205].

Table 3.

Some relevant examples of electrochemical assay of antioxidant activity and its key contributors [173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205].

5. Critical Perspectives and Comparative Conclusions

Analytical parameters of carbon-based sensors, analyte oxidation–reduction steps and potentials are influenced by analyte chemical structure (number and position of –OH groups or other substituents), electrode type, its development and interaction with the antioxidant molecule, as well as working conditions (matrix characteristics such pH or presence of interferences).

Studies performed on ascorbic acid electro-oxidation reveal irreversible voltammograms, consistent with the reported mechanism describing electrochemically reversible electron transfer, and a subsequent irreversible chemical process. During the first step, the oxidation of ascorbic acid involves liberation of two electrons and two protons, yielding dehydroascorbic acid. This electron transfer is followed by an irreversible solvation reaction at pH < 4.0. At pH values smaller than the first pKa value of L-ascorbic acid (around 4.5), two protons are exchanged during the process, whereas at higher pH values (4.5–8.0), a single proton is released, giving ascorbate anion as electroactive compound [206,207]. These described oxidation/solvation steps are consistent with the variation of the peak potential with pH, noticed up to pH 8.0, at a gold electrode: A pH increase from strong acidic to mild acidic and neutral values, results in anodic peak displacement to more positive values. Reported mechanistics aspects underlying ascorbic acid oxidation at pH > 8.0 imply ascorbate anion oxidation to a diketolactone, which by dehydration gives dehydroascorbic acid, that eventually suffers isomerisation to an ene-diol oxidizable at higher potentials [207].

Studies performed at a glassy carbon electrode modified by single-walled carbon nanotube/zinc oxide, proved that ascorbic acid anodic peak current increased with the increase of pH from 2 to 5, and reached a maximal value for pH comprised between pH 4 and 5. Then, the peak current progressively diminished as the pH increased from 6 to 10 and then increased again, for pH values found between 11 and 12. This confirms the involvement of deprotonation step in the oxidation of ascorbic acid. The oxidation peak shifted towards less positive potential values as the pH increased from 2 to 13. On the irreversible voltammograms obtained at the modified electrode, the oxidation potential shifted by approximately 240 mV towards a lower potential and the peak current doubled, when compared to the bare glassy carbon electrode, confirming electrocatalytical effect in a diffusion-controlled process (linear dependence of the current intensity on the square root of scan rate was observed) [208].

At a p-phenylenediamine film–holes modified glassy carbon electrodes, the cyclic voltammetric oxidation peak current of ascorbic acid increased, as the pH increased from pH 2 to 5. A further pH increase of the buffer resulted in a decrease of the analytical signal. This observation is consistent with the described analyte-electrode interaction: Within the pH range for which the modifier film is positively charged and the analyte is found in anionic form, the interaction of the modified glassy carbon electrode with ascorbic acid promotes the redox signal. With increasing pH value, the film may adopt a negative charge (caused by adsorption of free OH−), causing rejection of the anionic form of ascorbic acid. Therefore, the pH value of 5.0 was chosen as optimum, privileging interaction between the cationic film of modifier and the anionic form of analyte [209].

The analysis of anthocyanins by cyclic voltammetry at pH 7.0 revealed for kuromanine (cyanidin-3-O-glucoside) chloride and cyanin (cyanidin-3,5-O-diglucoside) chloride a first reversible peak at around 300 mV, due to the oxidation of catechol moiety present on the B-ring. The oxidized molecule can be subject to further oxidation at higher potential values yielding a second oxidation peak corresponding to the oxidation of the 5,7-dihydroxyl structure of the A-ring (resorcinol moiety). Given the different sensitivities of the techniques, the second peak obtained in cyclic voltammetry is smaller than that obtained in differential pulse voltammetry [129].

Studies on flavonoids reconfirmed first oxidation of the most redox active -OH groups present on ring B. Oxidations of the –OH groups present at C3 on ring C, and on the ring A (in resorcinol group) occur at more positive potentials. Studies on delphinidin anthocyanidin firstly reveal two peaks corresponding to oxidative processes involving -OH groups at 3′,4′,5′ positions (ring B), followed by a third peak corresponding to oxidation of -OH present on position 3 on ring C, and a fourth corresponding to oxidation of -OH groups present at positions 5 and 7 on ring A (resorcinol moiety) [128].

Oxidation of most ortho-diphenols occurs at close potentials, while mono-phenols are oxidized at higher potentials. Phenolic compounds that possess two −OH groups in ortho position on the aromatic ring, are reversibly oxidized to ortho-quinones: They give first peaks appearing on voltammograms, consistent with enhanced electron donating ability typically assigned to catechol-like polyphenols, endowed with highest antioxidant power. Most monophenols are subject to irreversible oxidation, due to only one –OH group. Ortho-diphenols present in olive oil, such as caffeic acid, hydroxytyrosol, and oleuropein are subject to reversible oxidation due to the presence of two hydroxyl groups in ortho position, exhibiting one anodic peak and one corresponding cathodic peak at the reverse scan. Tyrosol was irreversibly oxidized generating one anodic peak, due to the oxidation of only one −OH group present on the benzene ring, with the absence of the corresponding cathodic peak. Ferulic acid, a cinnamic acid derivative presenting only one −OH group, has one oxidation peak, and a much less configured reverse cathodic peak [188].

A cyclic voltammetric study performed on wine phenolics confirmed first oxidation of catechol moieties. Catechol-containing hydroxycinnamic acids, as main phenolics present in white wines exhibit a first peak at around 480 mV, followed by polyphenols with more positive potentials (900–1000 mV) such as coumaric acid and their derivatives. High molecular mass compounds resulting from oxidation of original white wine phenolics during storage can contribute to IInd peak. Catechin-type flavonoids, oligomeric and polymeric tannins present in red wines give a first peak around 440 mV; the second peak at around 680 mV was assigned to malvidin, with slight contribution from other phenolics such as trans-resveratrol; second oxidation of the catechin-type flavonoids resulted in a third anodic peak for red wines at 890 mV [137].

Yakovleva et al. performed an electroactivity-based general classification of the phenolic compounds under study (benzenediols, phenolic acids, flavonoids) into groups: Quercetin, dihydroquercetin, and phenolic acids with two −OH groups at ortho positions (2,3-dihydroxybenzoic, protocatechuic, and caffeic acid) are subject to reversible electro-oxidation at pH 6.0, below 400 mV; polyphenols with –OCH3 substituents present oxidation peaks in the range 400–600 mV; monophenols such as monohydroxyphenolic acids are oxidized at lower rate, having anodic peak potentials greater than 600 mV; the electron-donating groups −OH, −OCH3 or −CH3 present on the aromatic ring, were confirmed to render studied phenols more oxidizable. Monohydroxylated phenolics with methoxy substituents could be faster oxidized by electron donation than monohydroxyphenols lacking methoxy groups. It was stipulated that the mechanism underlying this trend is the stabilizing effect of the methoxy groups in the phenoxyl radical formed after electron loss by phenolic compounds [136].

In a study focused on the electrochemical behavior of anthocyanins and anthocyanidins, comparing myrtillin chloride (that has a pyrogallol group on the B-ring) with oenin chloride (that has a hydroxyl group on C4′, placed in ortho position with respect to two methoxy groups), the methoxy groups could not impart the previously discussed oxidation facility, the reverse effect being noticed: Hydroxyl group from pyrogallol moiety on the B-ring (the case of myrtillin chloride) was oxidized with greater facility than the hydroxyl group placed in the ortho position with respect to two methoxyl groups (the case of oenin chloride). Moreover, the hydroxyl group found in the ortho-position with respect two methoxyl groups (in oenin chloride), was more oxidizable than the catechol group placed in the ortho position with respect to a single methoxy group (in petunidin chloride) [129].

Electrochemical studies on phenolic antioxidants are performed in acid media or, most of them, close to physiological pH values, to hamper irreversible conversion of polyphenols at alkaline values. Cyclic voltammograms recorded for some phenolic acids and flavones at pH higher than 8.0 were characterized by irreversibility, and the anodic oxidation potential could not be precisely assessed [136]. It was asserted that phenolic acids can suffer dimerization and polymerization, synchronous with their oxidation by one-electron loss [210]. An increase of the pH value was corroborated with a linear diminution of the oxidation potentials in the case of anthocyanins. Moreover, an enhanced adsorption of the oxidation products (with fouling the electrode surface) was also noticed, correlated to a dramatic anthocyanins’ oxidation peaks decrease during second scan, at all pH values [129].

During a study performed on major phenolics present in coffee, an inverse linear dependence of oxidation peak potential vs pH was observed until reaching the pKa value, with a slope of approximately 59.2 mV, close to the Nerstian theoretical value, describing an electron:proton transfer processes. On the differential pulse voltammograms obtained for 0.5% w/v coffee sample, highest peak currents were noticed at middle-acid pH values (ranging between 5.0 and 6.0), while the slope was broken and peak currents diminished at alkaline pH of 8.0. The same observation was valid for voltammograms of hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives. It was concluded that the redox behavior of electroactive species from coffee samples is dominated by catechol-like main redox contributors, endowed with most enhanced antioxidant features [177].

A series of electroanalytical methods have proved their viability in antioxidant and antioxidant activity assay, largely employed being cyclic, differential pulse and amperometric techniques. In differential pulse and square wave techniques, the influence of capacitive currents is hampered, promoting sensitivity and detection of irreversible oxidation–reduction processes linked to the presence of minor electroactive contributors. Moreover, linear scan (cyclic voltammetric) techniques proved their viability in the comparative study of antioxidants’ electroactivity (relying on peak position), as well as in antioxidant capacity assay (based on the area under the anodic peak).

Carbonaceous electrode properties affecting electrochemical response are represented by surface properties, electronic structure, adsorption, electrocatalytical behavior and surface preparation [211]. The performances of carbon electrodes as working electrodes depend on the structure of the electrode, on the chemical bonds established between the carbon atoms, as these factors influence mechanical, conductive and chemical features. Considering allotropic carbon forms, diamond, whose structure is ensured by sp3 bonds, has poor conductivity, thus requiring boron dopping. Carbon allotropic forms whose structure is ensured by sp2 bonds are endowed with convenient electrical features, mainly conductivity.

Electrochemical determinations rely on surface phenomena and thus, electrode surface represents an important characteristic influencing analytical performances, reaction kinetics and interactions with the compounds to be analyzed. Electrode surfaces are commonly polished using alumina, mainly in the case of glassy carbon. A significant voltammetric current increase was reported in the case of gallic acid, chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, catechin, rutin and quercetin, as consequence of surface modification with alumina, by mere abrasive polishing [98]. It was found that modification of the glassy carbon electrode surface with small amounts of alumina can result in enhanced apparent catalysis of electron transfer involving catechol at low pH value. It was reported that catechol suffers adsorbtion on alumina, not directly on the electrode, so the process involves the triple boundary present between alumina particles, analyzed solution and the electrode. Enhancement of catechol redox process takes place at low pH, as such values facilitate the proton-coupled electron transfer at the previously-mentioned three-phase boundary [94]. The antioxidant capacity and activity, as well as the electrochemical index are significantly influenced by the presence of alumina in the case of tea, wine and phytotherapics samples. The improvement in detectability and sensitivity recommends the use of alumina-modified glassy carbon electrode for this assay. The shift of the anodic peak potentials towards less-positive values was reported, thus indicating that the electron transfer is promoted by surface modified with alumina. Nevertheless, the reported diminution in the difference between peak potentials (affecting peak-to-peak discrimination), may constitute a shortcoming in the case of surface modification with alumina [98].

Glassy carbon electrodes are prone to other modification methods: Electrode coating with ionic polymers was applied due to their ability to enhance conductive properties. A glassy carbon electrode coated with a thin film of poly(trihexylvinylbenzylammonium chloride) proved permselectivity to uric acid, that presented a linear voltammetric analytical response in the concentration range of 1–10 μM [212]. A glassy carbon electrode modified with multi-walled carbon nanotubes dispersed in polyhistidine allowed for simultaneous differential pulse voltammetric determination of ascorbic acid and paracetamol with improved analytical responses at minimized overvoltage and under diffusion control, benefiting from large electroactive area and enhanced electrocatalytical properties [213].

Electrolytes influence the surface of carbonaceous electrodes. Studies performed in sulfuric acid 4.5 M confirmed a change in composition of surface compounds, removal of finely crystalline graphite, as well as of unstable functional groups from the surface of activated carbon [214].

Conventional carbon-based sensors include glassy carbon, carbon fiber or pyrolytic graphite electrodes. Developing sensors at sizes below 100 nm is often a key characteristic that typically results in high surface area and improved surface/volume ratio. Other distinctive, attractive properties are swift electron transfer, enhanced electrocatalytic activity, improved interfacial adsorption and biocompatibility, when compared to other conventional materials [215,216]. Carbon-based nanomaterials composed of graphitic-type atoms linked by sp2 bonds, include fullerenes, carbon nanotubes and graphene. Their behavior depends on the interactions established with other materials and atomic or molecular structures [215,217,218,219,220]. These nanomaterials possess hollow or layered structures, and can establish non-covalent linkages with organic species through π-π stacking, hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, van der Waals or electrostatic forces [215,221].

Carbon nanomaterials are prone to combination with a series of other nanomaterials (based on noble metal nanocrystals, ceramics or Teflon) giving rise to nanocomposites with improved characteristics in a distinctive, novel material [215]. Previously reported novel application reveals that oxidation peaks of key analytes such as ascorbic acid, dopamine and uric acid at a ZnO nanosheet arrays/graphene foam sensor, are higher than those obtained at metal oxide-based (indium tin oxide) electrode, proving enhanced electrochemical features in the assay of both analytes, linked to the high conductivity of 3D porous graphene foam and large specific surface imparted by ZnO nanosheet arrays [222]. Diminished ascorbic acid overpotential and good peak-to-peak DPV separation for ascorbic acid vs dopamine (218.0 mV), dopamine vs paracetamol (218.0 mV), and ascorbic acid vs paracetamol (436.0 mV) were reported for platinum nanoparticles-decorated graphene nanocomposite electrode, with performances improved versus graphene-modified glassy carbon electrode and bare glassy carbon electrode [125]. A ZnO nanorods/graphene nanosheets/indium tin oxide hybrid electrode allowed good discrimination between uric acid and ascorbic acid, peaks at ZnO nanorods/indium tin oxide being not configured [150].

Carbon paste electrodes are synthesized by combining carbon-based materials (carbon nanotubes, microspheres or nanofibers, acetylene black, graphite and diamond,) with a binder (silicon oil or mineral oil) and largely used in antioxidant assay. A highly rigorous control over pasting liquid amount is required, as large amounts, although able to lower background currents, may diminish electron transfer rates [223,224]. These materials are easy to synthesize, inexpensive, possess reduced ohmic resistance, have broad potential range. They are prone to facile modification by using redox complexes, metal oxides or ionic surfactants, to improve performances in voltammetric assays [88]. The use of a carbon paste electrode modified with copper oxide-decorated reduced graphene enabled simultaneous voltammeric assay of ascorbic acid, uric acid and cholesterol, with sensitivity and good separation in SWV [127].

Employing printing technologies for rapid assay of electroactive species benefits from adaptability, compactibility, reduced costs, facility of large scale production, onsite application and easy modifier incorporation. Characteristics such as the employed ink material, the type of substrate, the choice of a particular electrochemical technique, the extent of waste generation, the obtained analytical performances, as well as shortcomings of each application of printed electrode should be considered. Researches should be focused on developing printed electrodes characterized by best analytical performances, lacking hazardous effects to the environment, to successfully replace conventional electrochemical cells [225].

The applications of chemical and biochemical carbon-based sensors encompass swift evaluation of key antioxidants and antioxidant activity in foodstuffs and dietary supplements, as well as in various biological media, these aspects being tightly related to screening/maintaining health status, hence the permanent interest in improving analytical performances and adaptability.

Electrode modification with single-, multiwalled carbon nanotubes or noble metal nanoparticles promotes electrocatalytical features, facilitating electron transfer: Peaks appear at lower potential and have higher corresponding current intensity. Hybrid nanosensors made of carbonaceous materials and metal/metal oxides enable for antioxidant signal separation and enhanced sensitivity in complex media.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.P.; A.P.; and A.I.S.; validation, F.I.; L.S.; and L.B.; formal analysis, A.M.P.; A.P.; and A.I.S.; investigation, A.M.P.; A.P.; F.I.; L.S.; L.B.; and A.I.S.; writing—original draft preparation A.M.P.; A.P.; and A.I.S.; writing—review and editing, F.I.; L.S.; and L.B.; visualization, F.I.; L.S.; L.B.; supervision, A.M.P. and A.I.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pisoschi, A.M.; Pop, A. The role of antioxidants in the chemistry of oxidative stress: A Review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 97, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoschi, A.M.; Pop, A.; Cimpeanu, C.; Predoi, G. Antioxidant capacity determination in plants and plant-derived products: A review. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 36, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoschi, A.M.; Pop, A.; Iordache, F.; Stanca, L.; Predoi, G.; Serban, A.I. Oxidative stress mitigation by antioxidants-an overview on their chemistry and influences on health status. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 209, 112891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, I. Antioxidants and antioxidant methods: An updated overview. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 651–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H.; Xu, L.; Porter, N.A. Free radical lipid peroxidation: Mechanisms and analysis. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 5944–5972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noguchi, N.; Watanabe, A.; Shi, H. Diverse functions of antioxidants. Free Radic. Res. 2001, 33, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ighodaro, O.M.; Akinloye, O.A. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): Their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alexandria J. Med. 2018, 54, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poljsak, B.; Suput, D.; Milisav, I. Achieving the balance between ROS and antioxidants: When to use the synthetic antioxidants. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013, 2013, 956792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Sánchez, N.F.; Salas-Coronado, R.; Villanueva-Cañongo, C.; Hernández-Carlos, B. Chapter 2, Antioxidant compounds and their antioxidant mechanism. In Antioxidants; Shalaby, E., Ed.; InTech Open: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, R.L.; Wu, X.; Schaich, K. Standardized methods for the determination of antioxidant capacity and phenolics in foods and dietary supplements. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 253, 4290–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, A.; Selga, A.; Torres, J.L.; Julia, L. Reducing activity of polyphenols with stable radicals of the TTM series. Electron transfer versus H-abstraction reactions in flavan-3-ols. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 4583–4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campesi, I.; Marino, M.; Cipolletti, M.; Romani, A.; Franconi, F. Put “gender glasses” on the effects of phenolic compounds on cardiovascular function and diseases. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 2677–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisoschi, A.M.; Pop, A.; Cimpeanu, C.; Turcus, V.; Predoi, G.; Iordache, F. Nanoencapsulation techniques for compounds and products with antioxidant and antimicrobial activity-a critical view. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 157, 1326–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carocho, M.; Morales, P.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Antioxidants: Reviewing the chemistry, food applications, legislation and role as preservatives. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 71, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunaciu, A.A.; Danet, A.F.; Fleschin, S.; Aboul-Enein, H.Y. Recent applications for in vitro antioxidant assay. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2016, 46, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apak, R.; Özyürek, M.; Güçlü, K.; Çapanoglu, E. Antioxidant activity/capacity measurement. 1. classification, physicochemical principles, mechanisms, and electron transfer (ET)-based assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 997–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, M.; Serban, A.; Popa, C.V.; Florescu, M. A nanoparticle-based label-free sensor for screening the relative antioxidant capacity of hydrosoluble plant extracts. Sensors 2019, 19, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brainina, K.; Stozhko, N.; Vidrevich, M. Antioxidants: Terminology, methods, and future considerations. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisoschi, A.M.; Negulescu, G.P. Methods for total antioxidant activity determination: A review. Biochem. Anal. Biochem. 2012, 1, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeer, N.B.; Montesano, D.; Albrizio, S.; Zengin, G.; Mahomoodally, M.F. The versatility of antioxidant assays in food science and safety-chemistry, applications, strengths, and limitations. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanet, R.; Coelho, C.; Liu, Y.; Bahut, F.; Ballester, J.; Nikolantonaki, M.; Gougeon, R.D. The antioxidant potential of white wines relies on the chemistry of sulfur-containing compounds: An optimized DPPH assay. Molecules 2019, 24, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Yang, L.; Xue, Q.; Yao, F.; Sun, J.; Yang, F.; Liu, Y. Antioxidant evaluation-guided chemical profling and structureactivity analysis of leaf extracts from five trees in Broussonetia and Morus (Moraceae). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilyasov, I.R.; Beloborodov, V.L.; Selivanova, I.A.; Terekhov, R.P. ABTS/PP decolorization assay of antioxidant capacity reaction pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turkiewicz, I.P.; Wojdyło, A.; Tkacz, K.; Nowicka, P.; Golis, T.; Bąbelewski, P. ABTS On-Line antioxidant, α-amylase, α-glucosidase, pancreatic lipase, acetyl-and butyrylcholinesterase inhibition activity of chaenomeles fruits determined by polyphenols and other chemical compounds. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.C.; Mazzer, A.; Clarkson, G.J.J.; Taylor, G. Antioxidant assays-consistent findings from FRAP and ORAC reveal a negative impact of organic cultivation on antioxidant potential in spinach but not watercress or rocket leaves. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 1, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, N.; Santiago, A.; Alías, J.C. Quantification of the antioxidant activity of plant extracts: Analysis of sensitivity and hierarchization based on the method used. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berker, K.I.; Güçlü, K.; Tor, I.; Demirata, B.; Apak, R. Total antioxidant capacity assay using optimized ferricyanide/prussian blue method. Food Anal. Methods 2010, 3, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, A.; Chen, S.; Xu, T.; Ren, Z.; Han, G.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of Chinese raisins produced in Xinjiang Province. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 2830–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özyürek, M.; Güçlü, K.; Tütem, E.; Başkan, K.S.; Erçağ, E.; Çelik, S.E.; Baki, S.; Yıldız, L.; Karamanc, Ş.; Apak, R. A comprehensive review of CUPRAC methodology. Anal. Methods 2011, 11, 2439–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çekiç, S.D.; Demir, A.; Başkan, K.S.; Tütem, E.; Apak, R. Determination of total antioxidant capacity of milk by CUPRAC and ABTS methods with separate characterisation of milk protein fractions. J. Dairy Res. 2015, 82, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalán, V.; Frühbeck, G.; Gómez-Ambrosi, J. Inflammatory and oxidative stress markers in skeletal muscle of obese subjects. In Oxidative Stress and Dietary Antioxidants; del Moral, A.M., García, C.M.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 163–189. [Google Scholar]

- De Leon, J.A.D.; Borges, C.R. Evaluation of oxidative stress in biological samples using the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances assay. J. Vis. Exp. 2020, 159, e61122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbouguerra, N.; Richard, T.; Saucier, C.; Garcia, F. Voltammetric behavior, flavanol and anthocyanin contents, and antioxidant capacity of grape skins and seeds during ripening (Vitis vinifera var. Merlot, Tannat, and Syrah). Antioxidants 2020, 9, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohtar, L.G.; Messina, G.A.; Bertolino, F.A.; Pereira, S.V.; Raba, J.; Nazareno, M.A. Comparative study of different methodologies for the determination the antioxidant activity of Venezuelan propolis. Microchem. J. 2020, 158, 105244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.K.; Koide, M.; Rao, T.P.; Okubo, T.; Ogasawara, Y.; Juneja, L.R. ORAC and DPPH assay comparison to assess antioxidant capacity of tea infusions: Relationship between total polyphenol and individual catechin content. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 61, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litescu, S.C.; Eremia, S.A.V.; Tache, A.; Vasilescu, I.; Radu, G.-L. The use of Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) and Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity (TEAC) assays in the assessment of beverages’ antioxidant properties. In Processing and Impact on Antioxidants in Beverages; Preedy, V., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 245–251. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Diez, R.; Rodriguez-Rojo, S.; Cocero, M.J.; Duarte, C.M.M.; Matias, A.A.; Bronze, M.R. Phenolic characterization of aging wine lees: Correlation with antioxidant activities. Food Chem. 2018, 259, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denev, P.; Todorova, V.; Ognyanov, M.; Georgiev, Y.; Yanakieva, I.; Tringovska, I.; Grozeva, S.; Kostova, D. Phytochemical composition and antioxidant activity of 63 Balkan pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) accessions. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2019, 13, 2510–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D. Methods for determination of antioxidant capacity: A review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2015, 6, 546–566. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, F.; Xu, T.; Lu, B.; Liu, R. Guidelines for antioxidant assays for food components. Food Front. 2020, 1, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomassetti, M.; Serone, M.; Angeloni, R.; Campanella, L.; Mazzone, E. Amperometric enzyme sensor to check the total antioxidant capacity of several mixed berries. Comparison with two other spectrophotometric and fluorimetric methods. Sensors 2015, 15, 3435–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tubaro, F.; Pizzuto, R.; Raimo, G.; Paventi, G. A novel fluorimetric method to evaluate red wine antioxidant activity. Period. Polytech. Chem. Eng. 2019, 63, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shpigun, L.K.; Arharova, M.A.; Brainina, K.Z.; Ivanova, A.V. Flow injection potentiometric determination of total antioxidant activity of plant extracts. Anal. Chim. Acta 2006, 573–574, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brainina, K.Z.; Stozhko, N.Y.; Buharinova, M.A.; Khamzina, E.I.; Vidrevich, M.B. Potentiometric method of plant microsuspensions antioxidant activity determination. Food Chem. 2019, 278, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevion, S.; Roberts, M.A.; Chevion, M. The use of cyclic voltammetry for the evaluation of antioxidant capacity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 28, 860–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, A.; Frontana, C. Evaluation of a carbon ink chemically modified electrode incorporating a copper-neocuproine complex for the quantification of antioxidants. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 313, 128070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubeckyj, R.A.; Winkler-Moser, J.K.; Fhaner, M.J. Application of differential pulse voltammetry to determine the efficiency of stripping tocopherols from commercial fish oil. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2017, 94, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofin, A.E.; Trinca, L.C.; Ungureanu, E.; Ariton, A.M. CUPRAC voltammetric determination of antioxidant capacity in tea samples by using screen-printed microelectrodes. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2019, 2019, 8012758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovagnoli-Vicuña, C.; Pizarro, S.; Briones-Labarca, V.; Delgadillo, A. A square wave voltammetry study on the antioxidant interaction and effect of extraction method for binary fruit mixture extracts. J. Chem. 2019, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savan, E.K. Square wave voltammetric (SWV) determination of quercetin in tea samples at a single-walled carbon nanotube (SWCNT) modified glassy carbon electrode (GCE). Anal. Lett. 2020, 53, 858–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordiienko, A.; Blaheyevskiy, M.; Iurchenko, I. A comparative study of phenolic compound antioxidant activity by the polarography method, using microsomal lipid peroxidation in vitro. Curr. Issues Pharm. Med. Sci. 2018, 31, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, M.; Tesanovic, K.; Gorjanovic, S.; Pastor, F.T.; Simonovic, M.; Glumac, M.; Pejin, B. Polarography as a technique of choice for the evaluation of total antioxidant activity: The case study of selected Coprinus Comatus extracts and quinic acid, their antidiabetic ingredient. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoschi, A.M.; Cimpeanu, C.; Predoi, G. Electrochemical methods for total antioxidant capacity and its main contributors determination: A review. Open Chem. 2015, 13, 824–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazhina, N.N. Determination of antioxidant activity of various bioantioxidants and their mixtures by the amperometric method. Russ. J. Bioorganic Chem. 2017, 43, 771–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tougas, T.P.; Jannetti, J.M.; Collier, W.G. Theoretical and experimental response of a biamperometric detector for flow injection analysis. Anal. Chem. 1985, 57, 1377–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milardovic, S.; Kerekovic, I.; Rumenjak, V. A flow injection biamperometric method for determination of total antioxidant capacity of alcoholic beverages using bienzymatically produced ABTS+. Food Chem. 2007, 105, 1688–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldoveanu, S. The utilization of gas chromatography/mass spectrometry in the profiling of several antioxidants in botanicals. In Advances in Chromatography; Guo, X., Ed.; InTech Open: London, UK, 2014; Chapter 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viet, T.D.; Xuan, T.D.; Van, T.M.; Andriana, Y.; Rayee, R.; Tran, H.-D. Comprehensive fractionation of antioxidants and GC-MS and ESI-MS fingerprints of celastrus hindsii leaves. Medicines 2019, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merken, H.M.; Beecher, G.R. Measurement of food flavonoids by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography: A review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 577–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, J.; Sun, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhao, R. Comparison of antioxidant activities and high-performance liquid chromatography analysis of polyphenol from different apple varieties. Int. J. Food Prop. 2016, 19, 2396–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorupa, A.; Gierak, A. Detection and visualization methods used in thin-layer chromatography. JPC J. Planar Chromat. 2011, 24, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwatidzo, L.; Dzomba, P.; Mangena, M. TLC separation and antioxidant activity of flavonoids from Carissa bispinosa, Ficus sycomorus, and Grewia bicolar fruits. Nutrire 2018, 43, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Pelle, F.; Compagnone, D. Nanomaterial-based sensing and biosensing of phenolic compounds and related antioxidant capacity in food. Sensors 2018, 18, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escarpa, A. Lights and shadows on food microfluidics. Lab Chip. 2014, 14, 3213–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellner, R.; Mermet, J.M.; Otto, M.; Valcarcel, V.; Widmer, H.M. (Eds.) Analytical Chemistry. A modern Approach to Analytical Science; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Milardovic, S.; Ivekovic, D.; Rumenjak, V.; Grabaric, B.S. Use of DPPH•/DPPH redox couple for biamperometric determination of antioxidant activity. Electroanalysis 2005, 17, 1847–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoschi, A.M. Biamperometric applications to antioxidant content and total antioxidant capacity assessment: An editorial. Biochem. Anal. Biochem. 2015, 4, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoschi, A.M.; Cheregi, M.C.; Danet, A.F. Total antioxidant capacity of some commercial fruit juices: Electrochemical and spectrophotometrical approaches. Molecules 2009, 14, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoschi, A.M.; Pop, A.; Gajaila, I.; Iordache, F.; Dobre, R.; Cazimir, I.; Serban, A.I. Analytical methods applied to the assay of sulfur-containing preserving agents. Microchem. J. 2020, 105, 104681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoschi, A.M.; Negulescu, G.P.; Pisoschi, A. Ascorbic acid determination by an amperometric ascorbate oxidase-based biosensor. Rev. Chim. 2010, 61, 339–344. [Google Scholar]

- Pisoschi, A.M. Biosensors as bio-based materials in chemical analysis: A Review. J. Biobased Mater. Bioenergy 2013, 7, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahcen, A.A.; Rauf, S.; Beduk, T.; Durmus, C.; Aljedaibi, A.; Timur, S.; Alshareef, H.N.; Amine, A.; Wolfbeis, O.S.; Salama, K.N. Electrochemical sensors and biosensors using laser-derived graphene: A comprehensive review. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 168, 112565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucherenko, I.S.; Soldatkin, O.O.; Dzyadevych, S.V.; Soldatkin, A.P. Electrochemical biosensors based on multienzyme systems: Main groups, advantages and limitations—A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1111, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sochor, J.; Dobes, J.; Krystofova, O.; Ruttkay-Nedecky, B.; Babula, P.; Pohanka, M.; Jurikova, T.; Zitka, O.; Adam, V.; Klejdus, B.; et al. Electrochemistry as a tool for studying antioxidant properties. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2013, 8, 8464–8489. [Google Scholar]

- Peres, A.M.; Sousa, M.E.B.; Veloso, A.C.A.; Estevinho, L.; Dias, L.G. Electrochemical sensors for assessing antioxidant capacity of bee products. In Chemistry, Biology and Potential Applications of Honeybee Plant-Derived Products; Susana, M.C., Artur, M.S.S., Eds.; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2016; pp. 196–223. [Google Scholar]

- David, M.; Serban, A.; Radulescu, C.; Danet, A.F.; Florescu, M. Bioelectrochemical evaluation of plant extracts and gold nanozyme-based sensors for total antioxidant capacity determination. Bioelectrochemistry 2019, 129, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, M.; Florescu, M.; Bala, C. Biosensors for antioxidants detection: Trends and perspectives. Biosensors 2020, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Ji, J.; Sun, Z.; Shen, P.; Sun, X. Recent advances in electrochemical biosensors for antioxidant analysis in foodstuff. Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 122, 115718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, R.; Chen, T.-W.; Chen, S.-M.; Rajaji, U.; Chinnapaiyan, S.; Chinnathabmi, S.; Subramanian, B.; Yu, J.; Yu, R. Electrochemical sensors and biosensors for redox analytes implicated in oxidative stress: Review. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2020, 15, 7064–7081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, L.D.; Kubota, L.T. Biosensors as a tool for the antioxidant status evaluation. Talanta 2007, 72, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barroso, M.F.; de-los-Santos-Álvarez, N.; Lobo-Castanón, M.J.; Miranda Ordieres, A.J.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P.; Tunon-Blanco, P. DNA-based biosensor for the electrocatalytic determination of antioxidant capacity in beverages. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2011, 26, 2396–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonanni, A.; Campanella, L.; Gatta, T.; Gregori, E.; Tomassetti, M. Evaluation of the antioxidant and prooxidant properties of several commercial dry spices by different analytical methods. Food Chem. 2007, 102, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.A.; Rebelo, M.J. A new laccase biosensor for polyphenols determination. Sensors 2003, 3, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böyükbayram, A.; Kıralp, S.; Toppare, L.; Yağci, Y. Preparation of biosensors by immobilization of polyphenol oxidase in conducting copolymers and their use in determination of phenolic compounds in red wine. Bioelectrochemistry 2006, 69, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, D.M.A.; Rebelo, M.J.F. Evaluating the antioxidant capacity of wines: A laccase-based biosensor approach. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2010, 231, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymundo-Pereira, P.A.; Silva, T.A.; Caetano, F.R.; Ribovski, L.; Zapp, E.; Brondani, D.; Bergamini, M.F.; Marcolino, L.H., Jr.; Banks, C.E.; Oliveira, O.N., Jr.; et al. Polyphenol oxidase-based electrochemical biosensors: A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1139, 198–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslu, B.; Ozkan, S.A. Electroanalytical application of carbon based electrodes to the pharmaceuticals. Anal. Lett. 2007, 40, 817–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vytras, K.; Svancara, I.; Metelka, R. Carbon paste electrodes in electroanalytical chemistry. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2009, 74, 1021–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apetrei, C.; Apetrei, I.M.; De Saja, J.A.; Rodriguez-Mendez, M.L. Carbon Paste electrodes made from different carbonaceous materials: Application in the study of antioxidants. Sensors 2011, 11, 1328–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svancara, I.; Walcarius, A.; Kalcher, K.; Vytřas, K. Carbon paste electrodes in the new millennium. Cent. Eur. J. Chem. 2009, 7, 598–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. Glassy carbon: A promising material for micro-and nanomanufacturing. Materials 2018, 10, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Shuang, S.; Dong, C.; Choi, M.M.F. Electrodeposition of palladium nanoparticles on fullerene modified glassy carbon electrode for methane sensing. Electrochim. Acta. 2012, 76, 288–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.A.; Almadi, R.; Yamani, Z.H. Indium tin oxide nanoparticle-modified glassy carbon electrode for electrochemical sulfide detection in alcoholic medium. Anal. Sci. 2018, 34, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Batchelor-McAuley, C.; Compton, R.C. Two-electron, two-proton oxidation of catechol: Kinetics and apparent catalysis. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2015, 119, 1489–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalraj, B.; Palanisamy, S.; Chen, S.M.; Kannan, R.S. Alumina polished glassy carbon electrode as a simple electrode for lower potential electrochemical detection of dopamine in its sub-micromolar level. Electroanalysis 2016, 28, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.P.; Almeida, P.L.; Sousa, R.M.; Richter, E.M.; Nossol, E.; Munoz, R.A.A. Effect of alumina supported on glassy-carbon electrode on the electrochemical reduction of 2, 4, 6-trinitrotoluene: A simple strategy for its selective detection. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019, 851, 113385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.P.; Souza, R.C.; Silva, M.N.T.; Gonçalves, R.F.; Nossol, E.; Richter, E.M.; Lima, R.C.; Munoz, R.A.A. Influence of Al2O3 nanoparticles structure immobilized upon glassy-carbon electrode on the electrocatalytic oxidation of phenolic compounds. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 262, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.P.; dos Santos, W.T.P.; Nossol, E.; Richter, E.M.; Munoz, R.A.A. Critical evaluation of voltammetric techniques for antioxidant capacity and activity: Presence of alumina on glassy-carbon electrodes alters the results. Electrochim. Acta. 2020, 358, 136925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walcarius, A. Analytical applications of silica-modified electrodes-A comprehensive review. Electroanalysis 1998, 10, 1217–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholmanov, I.; Cavaliere, E.; Fanetti, M.; Cepek, C.; Gavioli, L. Growth of curved graphene sheets on graphite by chemical vapor deposition. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 79, 233403–233406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Yang, Z.D.; Gao, L.J. Theoretical study of electronic properties of phenyl covalent functional carbon nanotubes. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 32, 259–264. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, C.N.R.; Sood, A.K.; Subrahmanyam, K.S.; Govindaraj, A. Graphene: The new two-dimensional nanomaterial. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 7752–7777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.W.; Li, F.; Liu, M.; Lu, G.Q.; Cheng, H.M. 3D aperiodic hierarchical porous graphitic carbon material for high-rate electrochemical capacitive energy storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Hyeon, T. Recent progress in the synthesis of porous carbon materials. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 2073–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Y.; Wang, W.; Wei, S. Hierarchical porous carbon obtained from animal bone and evaluation in electric double-layer capacitors. Carbon 2011, 49, 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]