Abstract

Fishermen operating in pelagic fisheries often experience significant barriers to medical care due to geographic isolation, harsh environmental conditions, and the absence of onboard healthcare personnel. Telemedicine offers an effective approach to overcome these limitations by enabling remote diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment through satellite-based communication systems. This review summarizes the progress and applications of telemedicine in maritime and other austere environments, focusing on technological advancements, clinical implementations, and emerging trends in artificial intelligence-driven healthcare. Evidence from pilot and retrospective studies highlights the growing use of wearable devices, telementored ultrasound, digital photography, and cloud-based monitoring systems for managing acute and chronic medical conditions at sea. The integration of machine learning and deep learning algorithms has further improved fatigue, stress, and motion detection, enhancing early risk assessment among seafarers. Despite challenges such as limited connectivity, data privacy concerns, and training requirements, the adoption of telemedicine significantly improves health outcomes, reduces emergency evacuations, and promotes occupational safety. Future directions emphasize the development of 5G-enabled Internet of Medical Things networks and predictive AI tools to establish comprehensive maritime telehealth ecosystems for fishermen in pelagic operations.

1. Introduction

Fishermen engaged in pelagic fisheries operate in some of the most isolated and challenging environments on Earth, spending extended periods at sea where access to timely medical care is severely limited [1,2]. The combination of physical labor, unpredictable weather, long working hours, and limited onboard medical infrastructure exposes them to a wide range of occupational health risks, including injuries, dehydration, fatigue, and psychological stress. In most cases, vessels lack qualified medical personnel, and crew members rely on basic first-aid knowledge, which is often insufficient during medical emergencies. These constraints highlight a persistent gap in healthcare accessibility for maritime workers—one that modern telemedicine is uniquely positioned to fill. Telemedicine, defined as the remote delivery of clinical healthcare using telecommunications and digital technology, has emerged as a practical and transformative approach to maritime healthcare [3]. By integrating satellite communication, portable diagnostic devices, and cloud-based data platforms, telemedicine enables real-time consultation between onboard crews and onshore medical professionals. This digital link allows for immediate evaluation of injuries, medical events, or psychological distress—conditions that previously required long delays or emergency evacuations. The evolution from traditional radio-based medical advice to interactive, video-enabled teleconsultation marks a major shift in how healthcare is delivered at sea, turning distant ships into mobile healthcare units connected to expert medical networks [4].

Recent technological advancements have accelerated this transition. Wearable biosensors now enable continuous monitoring of vital parameters such as heart rate, blood oxygen levels, and stress indicators, providing early warning of physiological deterioration. Portable ultrasound and electrocardiogram (ECG) devices allow for onboard imaging and cardiac assessments that can be transmitted instantly to telemedical assistance centers for interpretation. Meanwhile, the integration of cloud computing and artificial intelligence (AI) has enhanced data management and diagnostic precision, allowing for predictive health analysis and early intervention. These innovations together create a connected healthcare ecosystem capable of supporting both acute emergency response and long-term preventive health surveillance. The maritime sector’s adoption of telemedicine extends beyond immediate medical care; it represents a broader commitment to occupational safety, crew welfare, and sustainable fisheries management. For fishermen in pelagic operations, where voyages can span weeks or months, the ability to receive continuous medical supervision and expert consultation fundamentally improves health outcomes, operational efficiency, and morale. Moreover, the lessons learned from telemedicine in other extreme environments, such as Antarctic research bases and mountain expeditions, reinforce its reliability under austere conditions [4,5,6].

Hat et al. introduced the concept of the Human Digital Twin (HDT) as a digital replica of an individual designed to integrate human characteristics directly into system modeling and operational decision-making. This framework aims to revolutionize human–system interaction in maritime environments by enhancing situational awareness, predicting crew performance, and improving overall system reliability. However, the current development of HDT models has given limited attention to the cognitive processes that govern human perception, judgment, and decision-making during complex maritime operations. To address this gap, Hat et al. proposed a model-based framework that integrates the Information–Decision–Action of Crew model with a Discrete Dynamic Event Tree to dynamically capture changes in human cognition and behavior under varying conditions [7]. Their case study, conducted using a ship hydrodynamic simulator, demonstrated that the Cognitive Process-based HDT can quantitatively represent fluctuations in crew states and response mechanisms, offering a promising pathway for future telemedicine and maritime safety systems that rely on real-time human–machine integration.

Previous reviews have examined telemedicine applications in maritime shipping, polar expeditions, offshore energy platforms, and space-analog environments such as NASA’s NEEMO (NASA Extreme Environment Mission Operations) and HI-SEAS (Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation) missions. These studies typically focus on structured, institution-supported contexts with stable communication links, designated medical officers, and standardized emergency-response protocols. Similarly, reviews of Arctic and Antarctic expedition medicine emphasize telehealth integration within well-equipped research stations characterized by scheduled operations and robust logistical support. In contrast, fishermen engaged in pelagic operations experience far more variable and resource-limited conditions. Fishing vessels often lack trained medical personnel, operate with unpredictable travel routes, and rely on intermittent satellite connectivity while facing high rates of injuries, fatigue, environmental exposure, and delayed evacuation. Despite constituting one of the world’s most hazardous occupations, this group remains underrepresented in broader telemedicine syntheses. This review specifically addresses that gap by integrating technological, clinical, and AI-enabled perspectives tailored to the unique constraints of pelagic fisheries, highlighting operational realities that differ substantially from other austere telemedicine models. Finally, it discusses the benefits, challenges, and future perspectives of maritime telehealth, emphasizing the need for international collaboration to establish scalable and standardized systems capable of safeguarding the health and well-being of seafarers worldwide.

2. Technological Framework for Maritime Telemedicine

The advancement of telemedicine in maritime environments represents a transformative milestone in the way medical care is provided to individuals working in remote, high-risk occupations such as pelagic fisheries. Unlike terrestrial healthcare systems, where patients and clinicians can interact face-to-face or through stable network infrastructures, maritime healthcare delivery depends on the seamless coordination of satellite communication, onboard diagnostic technologies, data management systems, and artificial intelligence–driven analytical tools. The entire ecosystem must operate reliably under the constraints of unpredictable weather, limited power supply, and scarce medical personnel. As a result, the technological framework for maritime telemedicine must emphasize not only real-time connectivity but also system resilience, interoperability, and data security to ensure continuous and accurate healthcare support for fishermen operating far from the shore.

2.1. Ship-to-Shore Communication Systems

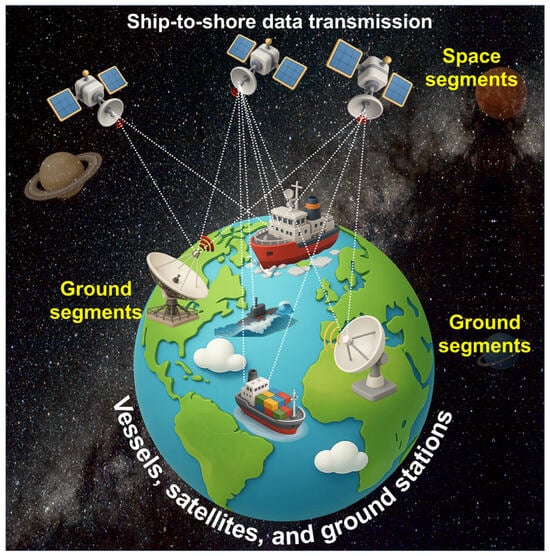

At the core of maritime telemedicine lies the ship-to-shore communication infrastructure, which enables the continuous transmission of medical information between vessels and onshore healthcare centers. This system is primarily powered by satellite networks such as Inmarsat FleetBroadband, Iridium Certus, and Very Small Aperture Terminal (VSAT) systems, which provide broadband connectivity across global maritime zones. Through these satellite links, clinical data, including electrocardiograms, ultrasound images, and real-time video streams, can be transmitted to telemedical assistance services (TMAS) that operate around the clock. Figure 1 illustrates the operational flow of this communication chain, where data originating from the ship’s medical workstation or wearable health devices are transmitted to orbiting satellites and relayed to receiving ground stations. These data are subsequently routed to hospitals, universities, or maritime telehealth centers, where physicians interpret the information and provide immediate diagnostic or therapeutic guidance [8,9].

Figure 1.

Ship-to-shore data transmission through satellite.

This communication model enables both synchronous and asynchronous telemedicine. In the synchronous mode, live video conferencing allows physicians to interact directly with the crew, observe symptoms, and guide emergency medical interventions such as wound suturing, defibrillation, or administration of intravenous therapy. In asynchronous communication, or “store-and-forward” telemedicine, medical data such as dermatological photographs or ultrasound scans are stored locally and transmitted when the connection stabilizes, ensuring continuous care despite bandwidth interruptions. The integration of these communication modalities has drastically reduced response times for medical emergencies at sea, minimized unnecessary helicopter evacuations, and increased diagnostic accuracy for conditions like cardiac arrhythmia, trauma, and infectious diseases. This framework is particularly vital for pelagic fishermen, who often remain at sea for weeks without access to land-based healthcare facilities, relying entirely on ship-to-shore connectivity for medical intervention [10].

2.2. Cloud-Based Monitoring and Data Integration

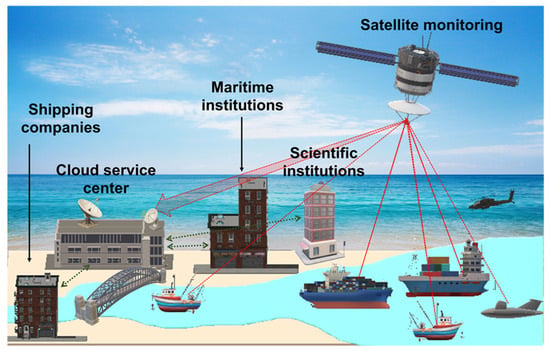

The second pillar of the maritime telemedicine framework is the incorporation of cloud computing for data management and real-time monitoring. Figure 2 represents this architecture, wherein medical data collected aboard vessels is transmitted through encrypted satellite links and stored within centralized cloud servers. These cloud systems serve as digital repositories that connect shipping companies, telemedical centers, maritime regulatory bodies, and scientific institutions under a unified data-sharing network. The cloud infrastructure ensures that each seafarer’s medical record, including diagnostic images, consultation histories, and physiological parameters, remains accessible to authorized healthcare professionals regardless of location. By integrating various data streams, this model creates a continuous feedback loop between ship and shore, fostering collaborative decision-making during emergencies and improving preventive healthcare planning [11].

Figure 2.

Practical applications for ship-to-shore data transmission by satellite monitoring through a cloud service center to shipping companies, maritime institutions, and scientific institutions.

Cloud-based systems also enable predictive analytics by processing large datasets accumulated from wearable devices, environmental sensors, and medical instruments. Artificial intelligence algorithms analyze fluctuations in physiological parameters, such as heart rate variability, body temperature, and oxygen saturation, to predict health risks like fatigue, heat stress, or dehydration before symptoms become clinically evident. Additionally, the combination of environmental monitoring data (including sea temperature, humidity, and air pressure) with physiological parameters allows for predictive modeling of occupational hazards specific to pelagic operations. During the COVID-19 pandemic, cloud-integrated telemedicine networks proved indispensable in managing onboard disease surveillance and quarantine coordination. Data integration ensured immediate triage and isolation protocols for suspected cases, thereby preventing onboard transmission and enabling safe continuation of fishing operations. Consequently, cloud-based telemedicine has evolved from a passive data storage model into an active, decision-supporting infrastructure for global maritime healthcare [12].

2.3. Integration of Portable Diagnostic Devices

The development and miniaturization of medical diagnostic instruments have revolutionized the feasibility of telemedicine aboard fishing vessels. Modern maritime telehealth systems now incorporate compact, ruggedized devices capable of providing hospital-grade diagnostics in confined shipboard environments. Handheld ultrasound scanners, for example, allow operators to capture high-quality images of internal organs, musculoskeletal structures, or cardiac conditions, which can be transmitted instantly via satellite to shore-based specialists. This innovation has proven particularly effective for diagnosing internal injuries, pneumothorax, or pericardial effusions during voyages when immediate evacuation is not possible. Similarly, portable ECG units and automated external defibrillators (AEDs) enable early detection and response to cardiovascular events—a leading cause of morbidity among fishermen and seafarers. Wearable health monitoring devices, such as wristbands or chest straps equipped with biosensors, continuously record heart rate, oxygen saturation, movement, and sleep patterns, transmitting these data in real time to cloud servers for medical supervision [5,13].

The adoption of these portable devices has not only improved emergency preparedness but also introduced a new paradigm of preventive healthcare at sea. Instead of focusing solely on crisis intervention, fishermen can now benefit from continuous physiological monitoring that helps detect fatigue accumulation, sleep disturbances, or dehydration before they impair performance. Studies summarized in this review confirm the growing reliability of these technologies in extreme environments, including polar expeditions and jungle operations, further validating their applicability in pelagic fisheries. By empowering crew members to perform first-line diagnostics under remote supervision, portable devices effectively extend the reach of medical expertise from hospitals to the open ocean, transforming vessels into floating health monitoring stations.

2.4. Artificial Intelligence and Decision Support Systems

The integration of AI represents a pivotal advancement in maritime telemedicine. Machine learning and deep learning algorithms can process large volumes of physiological and environmental data, enabling automated detection of abnormalities and generation of clinical alerts without requiring constant human oversight. As summarized, AI models such as Decision Tree, Random Forest, k-Nearest Neighbor, and Support Vector Machine have been applied for recognizing patterns of fatigue, stress, and motion among workers in demanding environments. More sophisticated deep learning models, including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) networks, have achieved remarkable accuracy in classifying mental fatigue and physical stress states, often exceeding 90% reliability. These analytical frameworks, when integrated with wearable devices aboard ships, can alert telemedical centers in real time when abnormal patterns are detected, such as elevated heart rate, reduced motion variability, or prolonged stress indicators [14].

AI-based decision support systems also facilitate predictive diagnostics and adaptive feedback. By continuously learning from historical health data and operational conditions, algorithms can anticipate the likelihood of specific medical events, such as heatstroke or cardiac arrhythmia, and automatically suggest preventive measures to crew members. The resulting system functions as a digital co-pilot for health, supplementing human medical judgment with algorithmic intelligence. For fishermen in pelagic operations, this predictive capability is particularly valuable because it allows for early intervention in environments where immediate evacuation is impractical. In essence, AI transforms telemedicine from a reactive support system into a proactive and anticipatory healthcare platform, aligning with the modern vision of precision maritime medicine [15].

2.5. Security, Interoperability, and System Resilience

The sensitive nature of medical data transmitted over global networks necessitates rigorous cybersecurity and interoperability standards. Maritime telemedicine systems employ multi-layer encryption, secure authentication protocols, and anonymization measures to safeguard patient information during transmission and storage. Given the diverse array of technologies involved, ranging from satellite and 4G/5G maritime broadband to shipboard Wi-Fi, interoperability becomes essential to ensure seamless communication between devices and networks. Systems must be designed to automatically switch between available communication channels based on signal strength and bandwidth availability, ensuring reliability even during adverse weather conditions or signal disruptions. Future advancements, including 5G-enabled maritime networks and the emerging Internet of Medical Things (IoMT), are expected to enhance bandwidth capacity and reduce latency, allowing for high-definition teleconsultations, real-time AI analytics, and continuous video diagnostics to become routine components of onboard healthcare [16,17].

Resilience is equally critical for the long-term sustainability of telemedicine at sea. Equipment must withstand vibration, humidity, and saline corrosion, while software systems should be capable of autonomous operation when temporarily disconnected from the cloud. Training programs for crew members are vital to ensure the correct usage of medical devices and adherence to teleconsultation protocols. The resilience of these systems thus depends not only on technology but also on human readiness and institutional collaboration among maritime operators, telehealth providers, and regulatory agencies. Together, these components create an adaptive ecosystem capable of maintaining healthcare delivery under the unpredictable conditions of pelagic fisheries.

3. Review of Telemedicine Studies in Maritime and Austere Environments

This provides a structured overview of the breadth of telemedicine research conducted across maritime and other isolated environments, categorizing the works by type of publication, environmental context, and thematic focus. The distribution of studies reveals a predominant emphasis on maritime healthcare, reflecting the global priority of improving medical accessibility for seafarers and fishermen working under physically demanding and geographically isolated conditions. Compared to other remote settings such as Antarctic stations, mountainous expeditions, or jungle operations, the maritime environment exhibits the highest concentration of telemedicine activities, underscoring its importance as a model setting for testing remote healthcare systems.

The entries in Table 1 are organized according to article type—pilot studies, case reports, qualitative studies, company reports, retrospective analyses, and commentaries—demonstrating a progressive evolution from feasibility assessments to structured telemedical operations. Pilot studies occupy a significant portion of the table, primarily addressing the initial deployment and performance evaluation of telemedical devices and systems. These include wearable digital health monitors, portable ultrasound imaging units, and telemonitoring tools for real-time physiological tracking. The recurring inclusion of ultrasound and telementoring categories indicates the central role of imaging and guided diagnostics in establishing reliable remote healthcare for maritime and expeditionary settings. The feasibility of ultrasound-based diagnosis and tele-guided procedures through satellite communication highlights the growing technological maturity of telemedicine in environments where conventional healthcare is unavailable.

Table 1.

Overview of Publications by Type and Environmental Context.

4. Medical Case Studies and Observations in Maritime Healthcare

The data compiled in Table 2 provide a comprehensive overview of how telemedicine has been applied across maritime operations through retrospective, observational, descriptive, and epidemiological analyses. Collectively, these studies highlight the evolution of telemedicine from isolated case-based support to a structured healthcare system capable of both emergency response and preventive medical management for seafarers. The findings encompass a broad range of sample sizes, from small clinical groups to extensive datasets exceeding several thousand maritime health cases, reflecting the increasing institutionalization of telemedical assistance at sea. Retrospective investigations demonstrate that telemedicine significantly improves the efficiency of medical response aboard ships. By enabling continuous ship-to-shore communication, medical assistance services can remotely assess the severity of onboard health incidents, provide immediate clinical guidance, and determine whether evacuation is necessary. This model has been instrumental in reducing the frequency of unnecessary emergency transfers, optimizing logistics, and minimizing operational downtime. The capacity to manage most injuries, infections, and acute illnesses remotely illustrates that teleconsultation has become a cornerstone of maritime health safety. Moreover, the recorded cases show that long-term implementation of telemedical systems enhances the consistency and documentation of health incidents, supporting occupational health surveillance across fleets.

Table 2.

Overview of Examined Studies: Study Type, Sample, Year, and Principal Observations.

Observational and descriptive analyses reinforce the role of telemedicine in broadening the scope of maritime healthcare. The use of teleconsultation platforms and remote diagnostic tools has enabled efficient management of both acute and chronic conditions, including cardiovascular disorders, musculoskeletal injuries, and dermatological issues. Crew members, often with limited medical training, can now perform guided diagnostic procedures such as ECG recording, basic wound care, and ultrasound imaging under real-time supervision from onshore specialists. This capability allows for prompt diagnosis, stabilization, and targeted treatment without delay. Chronic disease management has also benefited substantially, as periodic health monitoring and digital medical records facilitate early detection of conditions that could otherwise progress unnoticed during prolonged voyages. Epidemiological findings presented in the dataset reveal recurring patterns in maritime occupational health, such as higher injury and illness rates among specific job categories and age groups. Telemedicine has proven effective in identifying these trends through systematic data collection, contributing to the design of preventive programs and policy interventions aimed at improving crew welfare. The integration of continuous telemonitoring and digital reporting has allowed shipping companies and health authorities to analyze health statistics in real time, translating clinical data into actionable safety measures. This capacity for large-scale data aggregation positions telemedicine not only as a clinical service but also as an essential component of maritime public health surveillance.

A particularly important aspect of these findings concerns the application of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic, which served as a global validation of its value in emergency preparedness and outbreak control. Remote consultation systems were rapidly adapted to monitor symptoms, implement quarantine measures, and maintain communication between vessels and health authorities. Medical teams provided guidance for isolation, temperature tracking, and respiratory assessment, ensuring continuous operational safety while preventing disease transmission onboard. The pandemic also expanded the use of telemedicine for psychological support, addressing mental health challenges related to isolation and prolonged confinement. This period demonstrated that telemedicine can function as an integrated medical infrastructure, capable of supporting both clinical management and crisis mitigation under unprecedented conditions [3].

5. Integration of Artificial Intelligence in Telemedicine

The application of AI in telemedicine represents a major technological advancement that transforms traditional remote healthcare into an intelligent, adaptive, and predictive system. The summary presented in Table 3 highlights the growing implementation of AI models for health monitoring, focusing particularly on stress, fatigue, and motion detection. These models utilize various machine learning and deep learning architectures—including Decision Tree (DT), Random Forest (RF), k-nearest Neighbor (k-NN), Naive Bayes (NB), Support Vector Machine (SVM), CNN, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), and hybrid ensembles such as RF + SVM or CNN + LSTM + BiLSTM—to analyze physiological and behavioral data obtained from wearable or environmental sensors. Machine learning algorithms form the foundation of AI-based health monitoring by identifying subtle patterns in complex physiological datasets. In this framework, models such as DT, RF, and SVM are trained to classify variations in biometric signals—heart rate, body movement, or electroencephalogram (EEG) activity—that correspond to stress or fatigue levels. Their performance, as reflected in Table 3, shows reliability values between 70% and 85%, demonstrating their suitability for continuous physiological assessment in real-time maritime operations. Deep learning approaches extend this capability by employing multilayered neural networks that can automatically extract higher-order features from raw data. For example, CNN and BiLSTM architectures achieve accuracy levels exceeding 88% and, in some cases, approaching 99.9%, particularly when applied to mental fatigue classification using EEG inputs. Hybrid models that combine multiple algorithms provide even greater robustness, often surpassing 98% reliability, indicating strong potential for use in demanding and noisy environments like offshore fishing vessels. These AI systems are directly relevant to the health monitoring of fishermen who endure prolonged exposure to physically and mentally taxing marine conditions. Extended shifts, fluctuating temperatures, limited rest, and mechanical vibration collectively induce fatigue and stress—key factors influencing safety and productivity [57]. Integrating AI with wearable technologies allows for continuous assessment of these physiological responses, enabling early intervention before fatigue impairs decision-making or motor coordination. For example, an AI-enabled sensor network could alert ship officers when cumulative stress indices exceed safe thresholds, prompting mandatory rest periods or workload redistribution. The combination of algorithmic intelligence and sensor-based data acquisition transforms reactive medical assistance into a proactive safety management system, aligning telemedicine with preventive occupational health objectives. The reliability metrics summarized in Table 3 underscore the maturity of AI-assisted telemonitoring for real-world deployment. Consistently high accuracy levels across machine learning, deep learning, and hybrid categories suggest that these methods can effectively interpret data from non-invasive sensors such as smart bands, EEG headsets, or motion trackers. When integrated into maritime telemedicine frameworks, these AI models can operate through ship-to-shore cloud networks, allowing for real-time analysis and automated transmission of alerts to telemedical centers. Such integration not only enhances diagnostic precision but also reduces the cognitive and procedural workload on crew members, who can rely on automated systems to identify early signs of physiological decline [58]. In pelagic fisheries, most evidence supporting AI-assisted telemedicine originates from related occupational, clinical, or other austere environments rather than from large-scale validation studies conducted directly aboard fishing vessels. Although these studies indicate strong potential for AI-based fatigue, stress, and health monitoring among fishermen, direct validation under real pelagic fishing conditions remains limited. Accordingly, the AI applications discussed should be regarded as translational and prospective rather than fully validated for routine deployment.

Table 3.

AI Applications in Healthcare: Evidence from Empirical Studies.

6. Benefits and Challenges

6.1. Benefits

The implementation of telemedicine in maritime healthcare offers a range of tangible and far-reaching benefits, particularly for fishermen working in pelagic fisheries where conventional access to medical services is virtually impossible. One of the most significant advantages is the improved access to medical expertise. Through satellite-based communication and digital diagnostic tools, crew members can obtain direct consultation from qualified physicians and specialists located onshore. This eliminates the constraints of isolation and enables immediate professional evaluation of injuries, illnesses, or other medical emergencies. The ability to connect vessels to telemedical assistance centers ensures that expert advice is available around the clock, regardless of geographic location or environmental conditions. Another major benefit is the substantial reduction in response time and the associated cost of emergency evacuations. Before telemedicine was widely adopted, medical incidents at sea often required helicopter rescues or emergency docking—operations that were both logistically complex and financially burdensome. Telemedical systems allow for real-time triage and medical decision-making, ensuring that only critical cases are evacuated while non-emergency conditions are treated onboard under remote supervision. This targeted approach minimizes disruption to fishing operations and significantly reduces the financial strain on both maritime companies and national rescue services. Telemedicine also enables continuous health surveillance and preventive care, shifting the focus from reactive to proactive medical management. Wearable sensors and telemonitoring platforms collect physiological data such as heart rate, oxygen saturation, and stress indicators, which can be analyzed remotely to detect early signs of fatigue or illness. This continuous observation allows medical teams to provide early interventions, schedule rest periods, and recommend preventive measures before conditions escalate into emergencies. Such ongoing monitoring not only protects individual health but also contributes to maintaining overall operational efficiency. In addition, telemedicine enhances occupational safety by integrating health management into daily maritime operations. The ability to monitor crew health in real time ensures that potential risks—whether related to physical fatigue, dehydration, or psychological stress—are identified promptly. The inclusion of training modules and digital guidance within telemedical systems also empowers crew members with essential first-aid and emergency management skills. Together, these elements create a safer working environment, promoting both immediate well-being and long-term sustainability for those engaged in pelagic fishing operations [69].

6.2. Challenges

Despite its transformative potential, telemedicine in maritime applications faces several persistent challenges that must be addressed for widespread and effective adoption. The foremost technical limitation lies in bandwidth capacity and connectivity reliability. Satellite communication remains the primary link between ship and shore, but it is often constrained by weather interference, limited data throughput, and high operational costs. These factors can affect the quality of real-time video consultations and delay data transmission, particularly during adverse sea conditions. While emerging 5G maritime networks and low-earth-orbit satellite systems promise improvement, current infrastructure still poses a significant bottleneck for seamless medical communication. Another critical challenge involves the training requirements for both crew members and medical officers. Since telemedicine depends heavily on accurate data collection and the proper use of diagnostic devices, insufficient training can compromise the reliability of transmitted medical information. Crew personnel must be familiar with using wearable monitors, portable ultrasound devices, and telecommunication systems to ensure meaningful interactions with onshore physicians. Likewise, medical officers require specialized training in remote consultation protocols and cross-platform data interpretation to optimize clinical outcomes. Data privacy, cybersecurity, and ethical considerations also present growing concerns. The transmission of sensitive medical information through cloud-based systems introduces potential vulnerabilities to unauthorized access, data breaches, or misuse. Ensuring compliance with global data protection standards—such as GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) and maritime health regulations—is essential for safeguarding both personal privacy and institutional accountability. Encryption, anonymization, and secure authentication systems must be rigorously maintained to uphold ethical standards in digital healthcare delivery. Finally, telemedicine must be effectively integrated with existing maritime regulations and healthcare frameworks. The maritime sector operates under diverse international jurisdictions, each with distinct health, safety, and legal requirements. Achieving regulatory harmonization across these systems remains a challenge, as does defining liability in cases of remote medical misjudgment. Collaboration between maritime authorities, healthcare providers, and telecommunication agencies is necessary to develop standardized protocols that ensure interoperability, legal clarity, and consistent quality of care across fleets and regions [57].

7. Future Perspectives

The future of maritime telemedicine lies in integrating high-speed communication, intelligent analytics, and interconnected health systems to provide continuous medical support in remote oceanic environments. The deployment of 5G-enabled maritime networks will overcome current bandwidth limitations, allowing for high-resolution video consultations, real-time data streaming from wearable devices, and faster diagnostic communication between vessels and onshore medical centers. Combined with edge computing and low-earth-orbit satellite systems, 5G will create a stable and resilient framework for uninterrupted healthcare delivery at sea. The IoMT will further transform vessel-based healthcare by linking wearable biosensors, portable diagnostics, and cloud platforms into a unified digital ecosystem. Through continuous data exchange, IoMT can monitor vital signs, predict fatigue or dehydration, and enable proactive interventions to prevent medical emergencies among fishermen working in physically demanding pelagic operations. Integration of AI-enhanced telehealth systems will enable predictive diagnostics and personalized health management. Commonly used AI frameworks in remote and maritime telehealth include LSTM models for predicting physiological time-series data such as heart rate variation and fatigue progression, CNNs for image-based evaluation of wounds or burns transmitted from vessels, and Bayesian models for recognizing stress-related behavioral patterns during prolonged offshore work. These approaches support early identification of health risks and provide decision support in settings where skilled medical personnel are unavailable. By analyzing longitudinal physiological and behavioral data, AI can identify early disease markers, forecast fatigue or stress, and recommend corrective actions. These systems will extend telemedicine beyond emergency care to include chronic disease monitoring and mental health assessment, providing holistic well-being support for seafarers exposed to isolation and long working hours. To ensure global scalability, standardized policy and regulatory frameworks are needed to address data security, interoperability, and ethical governance. Collaborative efforts between international maritime and health organizations will be essential for harmonizing telemedical standards and ensuring equitable access to digital healthcare technologies worldwide. In essence, the convergence of 5G, IoMT, and AI will redefine maritime telemedicine as a predictive, connected, and globally regulated healthcare system—ensuring continuous, high-quality medical care for fishermen in pelagic fisheries [70].

8. Conclusions

Telemedicine has revolutionized healthcare accessibility for fishermen operating in pelagic fisheries by bridging the vast physical divide between sea and shore. Through satellite-based communication, wearable health monitoring devices, and cloud-integrated data systems, medical professionals can now provide real-time diagnosis, guidance, and preventive care to crews working in the most remote maritime environments. This transformation ensures that medical assistance, once limited by distance and time, is now immediate, continuous, and data-driven. The integration of wearable technologies, satellite connectivity, and artificial intelligence analytics has created a synergistic framework that enables continuous health surveillance, predictive diagnostics, and personalized intervention. These technologies collectively enhance safety, reduce medical evacuation costs, and promote long-term well-being by turning vessels into mobile healthcare units capable of autonomous monitoring and communication. Looking ahead, sustained progress in maritime telemedicine will depend on international collaboration to establish standardized frameworks for interoperability, cybersecurity, and ethical governance. Global partnerships among healthcare institutions, maritime organizations, and telecommunication providers are essential to scale these innovations and ensure equitable, resilient telehealth coverage for all seafarers. By embracing such collaboration, telemedicine can evolve into a universal system that safeguards the health, productivity, and dignity of maritime workers across the world’s oceans. Although artificial intelligence-enabled telemedicine shows strong promise for maritime healthcare, further field-based validation studies conducted directly in pelagic fisheries are required to confirm performance, reliability, and operational feasibility under real fishing conditions.

Author Contributions

P.-H.L. contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, and preparation of the original draft. C.-C.L. contributed to the conceptualization, validation, formal analysis, writing (review and editing), visualization, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan (CMRPGTP0011 to Lin CC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are included in the article’s reference list and are publicly available.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hunt, J.; Lucas, D.; Laforet, P.; Coulange, M.; Auffray, J.-P.; Dehours, E. Medical treatment of seafarers in the Southern Indian Ocean—Interaction between the French Telemedical Maritime Assistance Service (TMAS) and the medical bases of the French Southern and Antarctic Lands (TAAF). Int. Marit. Health 2022, 73, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, L.; Wang, S.; Fan, C.; Huang, D. Facilitating Patient Adoption of Online Medical Advice Through Team-Based Online Consultation. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagaro, G.G.; Battineni, G.; Chintalapudi, N.; Di Canio, M.; Amenta, F. Telemedical assistance at sea in the time of COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Marit. Health 2020, 71, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podugu, R.; Vamshi, P.B.; Chanumolu, S.K.; Uday, N.; Shibu, N.S.; Rao, S.N. Remote medical assistance for marine fishermen through oceannet. In Proceedings of the 2021 12th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Kharagpur, India, 6–8 July 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ting, L.; Wilkes, M. Telemedicine for patient management on expeditions in remote and austere environments: A systematic review. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2021, 32, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puskeppeleit, M.P. Improving Telemedicine Onboard Norwegian Ships and Drilling Platforms: A Study of Intersectoral Co-Operation in Maritime Medicine; Nordic School of Public Health NHV: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Li, F.; Lee, C.-H.; Wang, T.; Diaconeasa, M.A. Mirror the mind of crew: Maritime risk analysis with explicit cognitive processes in a human digital twin. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 62, 102746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh, N.; Gholamzadeh, M. Requirements, challenges, and key components to improve onboard medical care using maritime telemedicine: Narrative review. Int. J. Telemed. Appl. 2023, 2023, 9389286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battineni, G.; Chintalapudi, N.; Amenta, F. Maritime telemedicine: Design and development of an advanced healthcare system called marine doctor. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anogianakis, G.; Maglavera, S.; Pomportsis, A. Relief for maritime medical emergencies through telematics. IEEE Trans. Inf. Technol. Biomed. 2002, 2, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.B.; Tariq, F.; Sumra, I.A.; Rasheed, K. The Digital Evolution of the Maritime Industry: Unleashing the Power of IoT and Cloud Computing. J. Comput. Biomed. Inform. 2025, 9, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.S.; Ganesh, D. Improving telemedicine through IoT and cloud computing: Opportunities and challenges. Adv. Eng. Intell. Syst. 2024, 3, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Battineni, G.; Chintalapudi, N.; Gagliardi, G.; Amenta, F. The use of radio and telemedicine by TMAS Centers in provision of medical care to seafarers: A systematic review. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindle, R.D.; Badawi, O.; Celi, L.A.; Sturland, S. Intensive care unit telemedicine in the era of big data, artificial intelligence, and computer clinical decision support systems. Crit. Care Clin. 2019, 35, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battineni, G.; Chintalapudi, N.; Ricci, G.; Ruocco, C.; Amenta, F. Exploring the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and augmented reality (AR) in maritime medicine. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Fan, X.; Xu, S.; Cao, Y.; Chen, X.B.; Shang, T.; Yu, S. Anonymity-enhanced Sequential Multi-signer Ring Signature for Secure Medical Data Sharing in IoMT. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 5647–5662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagaro, G.G.; Amenta, F. Past, present, and future perspectives of telemedical assistance at sea: A systematic review. Int. Marit. Health 2020, 71, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-R.; Park, J.-H.; Jang, M.-W.; Sung, M.-J.; Song, S.-H.; Huh, U.; Ra, Y.-J.; Tak, Y.-J. Feasibility of Wearable Digital Healthcare Devices Among Korean Male Seafarers: A Pilot Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheit, L.; Dengler, D.; Belz, L.; Reck, C.; Harth, V.; Oldenburg, M. Pilot study on the development of digitally supported health promotion for seafarers on sea. Int. Marit. Health 2025, 76, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, N.; Mozetic, V.; Modrcin, B.; Jaksic, S. Might telesonography be a new useful diagnostic tool aboard merchant ships? A pilot study. Int. Marit. Health 2006, 57, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Latifi, R.; Stanonik, M.d.L.; Merrell, R.C.; Weinstein, R.S. Telemedicine in extreme conditions: Supporting the Martin Strel Amazon swim expedition. Telemed. E-Health 2009, 15, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBeth, P.B.; Hamilton, T.; Kirkpatrick, A.W. Cost-effective remote iPhone-teathered telementored trauma telesonography. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2010, 69, 1597–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBeth, P.B.; Crawford, I.; Blaivas, M.; Hamilton, T.; Musselwhite, K.; Panebianco, N.; Melniker, L.; Ball, C.G.; Gargani, L.; Gherdovich, C. Simple, almost anywhere, with almost anyone: Remote low-cost telementored resuscitative lung ultrasound. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2011, 71, 1528–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnardot, L.; Rainis, R. Store-and-forward telemedicine for doctors working in remote areas. J. Telemed. Telecare 2009, 15, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkpatrick, A.W.; McKee, J.L.; McBeth, P.B.; Ball, C.G.; LaPorta, A.; Broderick, T.; Leslie, T.; King, D.; Beatty, H.E.W.; Keillor, J. The Damage Control Surgery in Austere Environments Research Group (DCSAERG): A dynamic program to facilitate real-time telementoring/telediagnosis to address exsanguination in extreme and austere environments. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017, 83, S156–S163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satava, R.M. Telemedicine and Real-Time Monitoring. Telemed. Teledermatol. 2003, 32, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz, R.Y.; Ridge, G.E. Paederus dermatitis in a seafarer diagnosed via telemedicine collaboration. J. Travel Med. 2016, 23, taw017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-h. Exploring Healthcare Challenges and Stress Management in the Isolated Maritime Environment: A Qualitative Study on Seafarers’ Experiences. Asia-Pac. J. Converg. Res. Interchange 2024, 21, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashishth, T.K.; Sharma, V.; Kumar, S.; Verma, N.; Vidyant, S.; Kaushik, S. The Integration of AI in Telemedicine Transforming Healthcare Delivery and Patient Outcomes. In AI-Driven Personalized Healthcare Solutions; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 71–98. [Google Scholar]

- Dehours, E.; Tourneret, M.-L.; Roux, P.; Tabarly, J. Benefits of photograph transmission for trauma management in isolated areas: Cases from the French tele-medical assistance service. Int. Marit. Health 2016, 67, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, C.A.; Shemenski, R.; Drudi, L. Real-time tele-echocardiography: Diagnosis and management of a pericardial effusion secondary to pericarditis at an Antarctic research station. Telemed. E-Health 2012, 18, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehours, E.; Saccavini, A.; Roucolle, P.; Roux, P.; Bounes, V. Added value of sending photograph in diagnosing a medical disease declared at sea: Experience of the French Tele-Medical Assistance Service. Int. Marit. Health 2017, 68, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyer, R.N. Telemedical experiences at an Antarctic station. J. Telemed. Telecare 1999, 5, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.; Sikka, N.; O’Connell, F.; Dyer, A.; Boniface, K.; Betz, J. Telepsychiatric assessment of a mariner expressing suicidal ideation. Int. Marit. Health 2015, 66, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, A.; Angood, P. Advancing technologies in clinical medicine: The Yale-Mount Everest telemedicine project. Yale J. Biol. Med. 1999, 72, 19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Norum, J.; Moksness, S.G.; Larsen, E. A Norwegian study of seafarers’ and rescuers’ recommendations for maritime telemedicine services. J. Telemed. Telecare 2002, 8, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehours, E.; Vallé, B.; Bounes, V.; Girardi, C.; Tabarly, J.; Concina, F.; Pujos, M.; Ducassé, J.-L. User satisfaction with maritime telemedicine. J. Telemed. Telecare 2012, 18, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, S.S.; Amenta, F. Eighty years of CIRM. A journey of commitment and dedication in providing maritime medical assistance. Int. Marit. Health 2016, 67, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karitis, K.; Zoulias, E.; Liaskos, J.; Mantas, J. Information System for Supporting Seafarer’s Health Incident Reporting. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2025, 323, 233–237. [Google Scholar]

- Ohno, G.; Watanabe, K.; Okada, Y.; Higuchi, K. Practical experience of telehealth between an Antarctic station and Japan. J. Telemed. Telecare 2012, 18, 473–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.; Lanier, R.; Diven, D. A review of the practices and results of the UTMB to South Pole teledermatology program over the past six years. Dermatol. Online J. 2010, 16, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagaro, G.G.; Amenta, F. Telemedicine-Assisted Work-Related Injuries Among Seafarers on Italian-Flagged Ships: A 13-Year Retrospective Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheit, L.; Oldenburg, B.; Dirksen-Fischer, M.; Ehlers, L.; Harth, V.; Oldenburg, M. Maritime Use of Automated External Defibrillators (AED): Retrospective Assessment of Availability and Effectiveness. J. Mar. Med. Soc. 2025, 10, 4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallé, B.; Camelot, D.; Bounes, V.; Parant, M.; Battefort, F.; Ducassé, J.-L.; Pujos, M. Cardiovascular diseases and electrocardiogram teletransmission aboard ships: The French TMAS experience. Int. Marit. Health 2010, 62, 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Waterman, B.R.; Laughlin, M.D.; Belmont, P.J., Jr.; Schoenfeld, A.J.; Pallis, M.P. Enhanced casualty care from a global military orthopaedic teleconsultation program. Injury 2014, 45, 1736–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, C.; Shemenski, R.; Scott, J.M.; Hartshorn, J.; Bishop, S.; Viegas, S. Evaluation of tele-ultrasound as a tool in remote diagnosis and clinical management at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station and the McMurdo Research Station. Telemed. E-Health 2013, 19, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glinkowski, W.M.; Cedro, T.; Wołk, A.; Doniec, R.; Wołk, K.; Wilk, S. Telemedicine, eHealth, and Digital Transformation in Poland (2014–2024): Trends, Specializations, and Systemic Implications. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tareen, M.; Omar, L.; Gassas, L.; Ahmed, D.; Naleem, S.; Parsons, V. Homeworking among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Occup. Med. 2024, 74, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitton, M.J. Telemedicine at sea and onshore: Divergences and convergences. Int. Marit. Health 2015, 66, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herttua, K.; Gerdøe-Kristensen, S.; Vork, J.C.; Nielsen, J.B. Age and nationality in relation to injuries at sea among officers and non-officers: A study based on contacts from ships to Telemedical Assistance Service in Denmark. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e034502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, T.-E.; Tveten, A.; Dahl, E. Medical emergencies on large passenger ships without doctors: The Oslo-Kiel-Oslo ferry experience. Int. Marit. Health 2017, 68, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagaro, G.G.; Dicanio, M.; Battineni, G.; Samad, M.A.; Amenta, F. Incidence of occupational injuries and diseases among seafarers: A descriptive epidemiological study based on contacts from onboard ships to the Italian Telemedical Maritime Assistance Service in Rome, Italy. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apostolatos, C.; Andria, V.; Licari, J. Overall comparative analysis of management and outcomes of cardiac cases reported on board merchant ships. Int. Marit. Health 2017, 68, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafran-Dobrowolska, J.; Renke, M.; Wołyniec, W. Telemedical maritime assistance service at the University Center of Maritime and Tropical Medicine in Gdynia. The analysis of 6 years of activity. Med. Pracy. Work. Health Saf. 2020, 71, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehours, E.; De Camaret, E.; Lucas, D.; Saccavini, A.; Roux, P. The COVID-19 pandemic and maritime telemedicine: 18-month report. Int. Marit. Health 2022, 73, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Canio, M.; Burzi, L.; Ribero, S.; Amenta, F.; Quaglino, P. Role of teledermatology in the management of dermatological diseases among marine workers: A cross-sectional study comparing general practitioners and dermatological diagnoses. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 955311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Rehman, S. Integrating Artificial Intelligence into Telemedicine: Evidence, Challenges, and Future Directions. Cureus 2025, 17, e90829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramessur, R.; Raja, L.; Kilduff, C.L.; Kang, S.; Li, J.-P.O.; Thomas, P.B.; Sim, D.A. Impact and challenges of integrating artificial intelligence and telemedicine into clinical ophthalmology. Asia-Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 10, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, A.; Ghahramani, A.; Becerik-Gerber, B. Monitoring fatigue in construction workers using physiological measurements. Autom. Constr. 2017, 82, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L.; Jones, K. A case for the use of deep learning algorithms for individual and population level assessments of mental health disorders: Predicting depression among China’s elderly. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 369, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.J.; Cardoso, J.M.; Mendes-Moreira, J. k NN prototyping schemes for embedded human activity recognition with online learning. Computers 2020, 9, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, A.; Garg, S.; Tigga, N.P. Predicting anxiety, depression and stress in modern life using machine learning algorithms. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 167, 1258–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebelli, H.; Khalili, M.M.; Lee, S. A continuously updated, computationally efficient stress recognition framework using electroencephalogram (EEG) by applying online multitask learning algorithms (OMTL). IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2018, 23, 1928–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehmood, I.; Li, H.; Qarout, Y.; Umer, W.; Anwer, S.; Wu, H.; Hussain, M.; Antwi-Afari, M.F. Deep learning-based construction equipment operators’ mental fatigue classification using wearable EEG sensor data. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2023, 56, 101978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Gu, B.; Cao, S.; Fang, D. Identifying mental fatigue of construction workers using EEG and deep learning. Autom. Constr. 2023, 151, 104887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Layek, M.A. StackEnsembleMind: Enhancing well-being through accurate identification of human mental states using stack-based ensemble machine learning. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2023, 43, 101405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, S.; Anjum, N.; Masood, N.; Khattak, A.S.; Ramzan, N. A novel hybrid deep learning model for human activity recognition based on transitional activities. Sensors 2021, 21, 8227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manalu, H.V.; Rifai, A.P. Detection of human emotions through facial expressions using hybrid convolutional neural network-recurrent neural network algorithm. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2024, 21, 200339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, M.A.; Turner, A.W. Benefits of integrating telemedicine and artificial intelligence into outreach eye care: Stepwise approach and future directions. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 835804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrell, D.N. Dynamic evaluation approaches to telehealth technologies and artificial intelligence (AI) telemedicine applications in healthcare and biotechnology organizations. Merits 2023, 3, 700–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.