Abstract

Background: Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is characterized by repetitive complete or partial closure of the upper airway during sleep, which is a potentially life-threatening disorder. A cephalogram is a simple and effective examination to predict the risk of OSA in orthodontic clinical practice. This study aims to analyze the relationship between craniofacial characteristics and the severity of OSA using polysomnography and cephalogram data. Gender differences in these parameters are also investigated. Methods: This study included 112 patients who underwent a complete clinical examination, standard polysomnography study, and cephalometric analysis to diagnose obstructive sleep apnea. This study divided the participants into male and female groups to study the correlation between cephalometric parameters and the severity of OSA. The analysis involved 39 cephalometric parameters. The severity of obstructive sleep apnea was evaluated by the apnea–hypopnea index (AHI) and the lowest nocturnal oxygen saturation (LSaO2). Results: The final assessment included 112 adult participants (male/female = 67:45, mean age: 28.4 ± 7.29 years, mean male age: 28.8 ± 7.62 years, mean female age: 27.8 ± 6.79 years). Multivariate analysis revealed that the mandibular position, incisor inclination, facial height, and maxillary first molar position were strongly associated with OSA severity. Gender-specific differences in cephalometric predictors were identified, with distinct parameters correlating with the AHI and LSaO2 in males and females. Notably, the LSaO2 demonstrated stronger associations with craniofacial morphology in females than males. Conclusions: Cephalometric analysis can be effective in assessing the risk and severity of OSA based on the correlation between cephalometric parameters and the AHI/LSaO2. There is a clear difference between the cephalometric parameters associated with OSA severity in male and female individuals. This gender-dependent pattern may assist the personalized diagnosis and management of OSA in clinical practice.

1. Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) refers to a prevalent disorder characterized by repetitive episodes of upper airway collapse during sleep that disrupts normal sleep patterns and ventilation, resulting in symptoms such as snoring, witnessed apnea, and excessive daytime sleepiness [1]. As a very common but frequently undiagnosed disease, recent estimates suggest that OSA affects 9% of middle-aged men and 4% of adult women, with approximately half experiencing moderate-to-severe forms of the condition [2,3]. Risk factors for OSA include obesity, male sex, age, menopause, hypothyroidism, goiter (independent of thyroid function), fluid retention, adenotonsillar hypertrophy, and smoking [4,5]. In pediatric patients, OSA has been associated with neurocognitive deficits, difficulties in learning, behavioral issues, stunted growth, and impaired cardiac function [6,7]. The elderly population is particularly vulnerable to this global health issue since untreated OSA is linked to a number of potential negative health consequences, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, stroke, atherosclerosis, and an elevated risk of cardiovascular mortality [8,9]. Therefore, early screening and diagnosis are essential for reducing the negative impact of OSA on general health. While standard polysomnography (both in-lab and home-based PSG) remains the gold standard for OSA diagnosis, it does not inherently provide detailed morphological evaluation of the craniofacial region. This limitation underscores the need for adjunctive tools to identify anatomical risk factors of OSA, especially for those who may receive orthodontic or orthognathic treatment [10,11]. Anatomical parameters including airway width and length, hyoid bone position, tongue volume, and other craniofacial structures are determinate factors in the pathogenesis of certain OSA cases, hence complementary diagnostic tools are needed for a comprehensive evaluation of these factors [12].

Although advanced imaging techniques such as cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been widely adopted for evaluating the morphological details of orofacial structures, cephalometry persists as a valuable diagnostic tool for assessing skeletal and soft-tissue relationships. Its continued relevance in clinical practice stems from three key advantages: the cost-effectiveness compared to higher-resolution modalities, significantly reduced radiation exposure, and a technical simplicity that enables efficient implementation in routine screening protocols [13,14]. Certain craniofacial skeletal abnormalities have been linked to an increased risk of OSA, such as maxillary and mandibular retrognathia, an increased mandibular plane angle, and an inferiorly positioned hyoid bone, which makes lateral cephalogram an effective tool for the early screening of OSA [15,16]. The current diagnostic and severity grading criteria for OSA are primarily based on the apnea–hypopnea index (AHI), which represents the number of apnea and/or hypopnea events occurring per hour during sleep, regardless of the related nocturnal oxygen desaturation. The severity of OSA can be classified as mild (6 ≤ AHI ≤ 15), moderate (16 ≤ AHI ≤ 29), or severe (AHI ≥ 30) [17]. Similarly, most of the cephalometric studies have investigated the correlation between craniofacial morphological characteristics and the severity of OSA based solely on the AHI [15]. However, substantial evidence suggests that the AHI alone does not fully reflect the clinical symptoms and prognosis of patients with OSA. Mediano et al. reported that patients with similar AHIs may exhibit varying levels of daytime sleepiness, sleep latency, and nocturnal oxygenation [18]. Asano et al. found that although some patients share a similar mean AHI, the severity of hypoxia and incidence of cardiovascular events were significantly different [19]. Wang et al. suggested that an oxygen saturation below 90% during the total sleep time was independently associated with the risk of hypertension in patients with severe OSA, even after adjustment for traditional risk factors such as the AHI and body mass index (BMI) [20]. Building upon existing evidence, systematic evaluation of cephalometric correlations with nocturnal oxygen saturation in patients with OSA represents a critical step in identifying anatomical predictors of hypoxia risk and informing clinical management strategies. This study aims to investigate cephalometric predictors of OSA severity by analyzing craniofacial morphology through lateral cephalometric radiography. Two polysomnographic parameters—the AHI and LSaO₂—are utilized as primary severity indicators, enabling the identification of skeletal and soft-tissue biomarkers associated with OSA severity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Samples

The study was designed as a retrospective study. The study population consisted of patients referred to the Department of Orthodontics at the Hospital of Stomatology, Sun Yat-sen University, between January 2018 and July 2024. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Hospital of Stomatology, Sun Yat-sen University (Approval No.KQEC-2024-99-01). The inclusion criteria included the following: age over 18 years; a diagnosis for OSA confirmed by polysomnography (PSG); and the availability of a digital lateral cephalogram taken with the same cephalostat with the patient in an upright position, with a natural head posture and centric occlusion [21]. Patients were excluded if they had undergone continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment, had craniofacial or growth abnormalities, or had a history of orthodontic treatment or craniofacial trauma and surgery. Based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria, a total of 112 patients were included in this observational prospective study. All data used in this study were obtained from medical record review.

2.2. PSG

All participants underwent standard overnight polysomnographic monitoring, which included EEGs (C3/A2 and C4/A1, measured using surface electrodes), electrooculograms (measured using surface electrodes), submental electromyograms (measured by surface electrodes), nasal airflow (measured using a nasal cannula with a pressure transducer), oral airflow (measured with a thermistor), chest wall and abdominal movements (recorded by inductance plethysmography), electrocardiography, and pulse oximetry. Respiratory events were classified according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Criteria 2012 (version 2.0) [22]. The AHI was defined as apneas plus hypopneas per hour during sleep. Consistent with the 2012 criteria, hypopneas were defined as ≥30% reductions in airflow accompanied by either a ≥3% oxygen desaturation or an arousal. The AHI and lowest oxygen saturation (LSaO2) were recorded for further analysis in this study.

2.3. Cephalometric Analysis

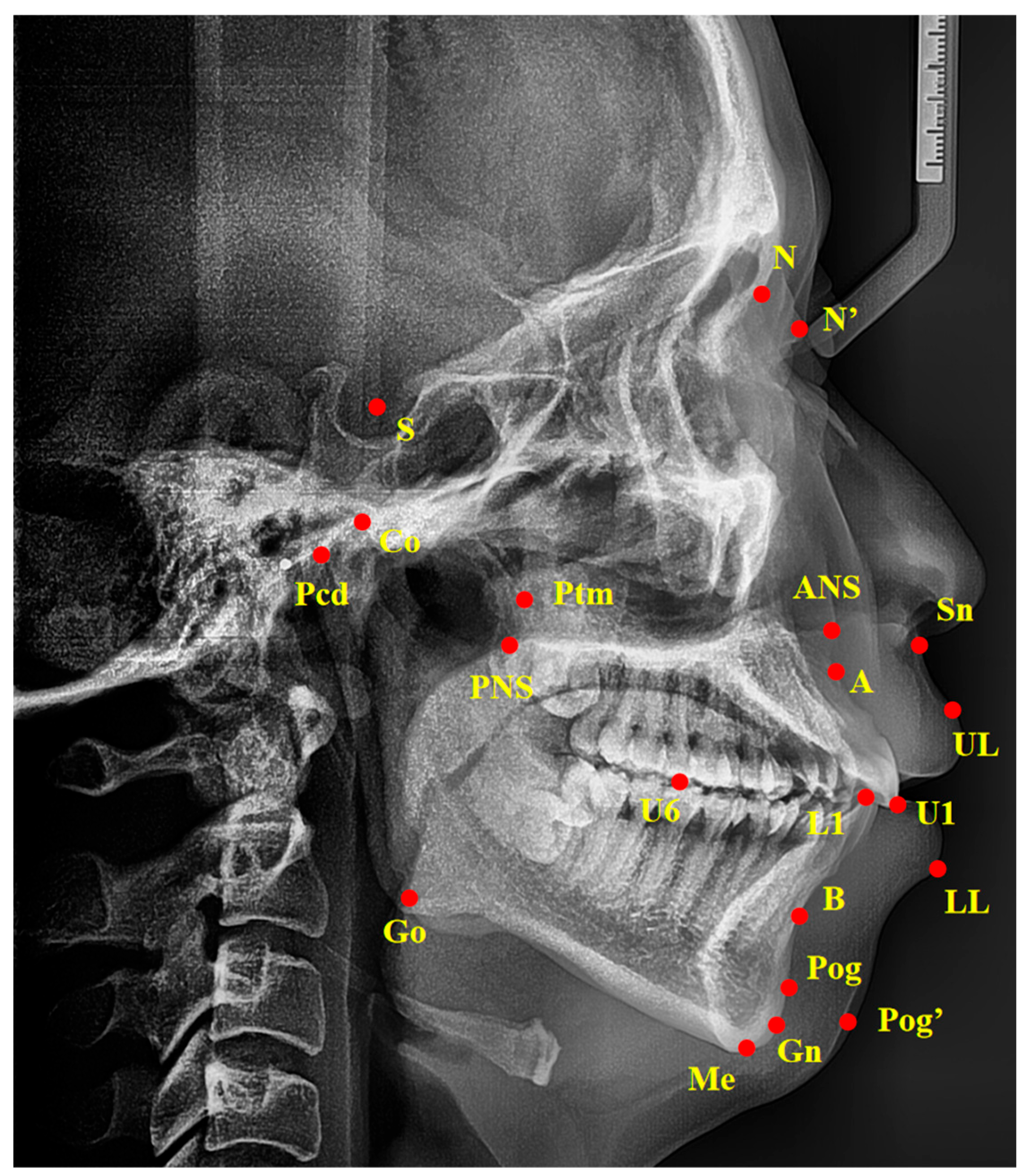

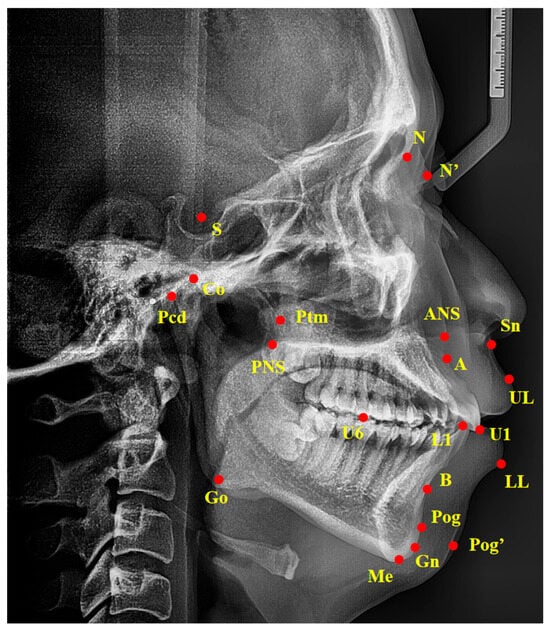

Standardized lateral cephalograms were taken with the same cephalostat at the Hospital of Stomatology, Sun Yat-sen University, with the patient in an upright position, with a natural head posture and centric occlusion. Cephalometric tracings were performed by an examiner blind to the PSG reports and clinical examination results, using the Digident software, version 2.10 (Boltzmann Zhibei Technology Co., Ltd., Chengdu, China) to calculate all angular and linear measurements [23]. All landmarks were automatically digitized and manually adjusted on each radiograph. Thirty-nine variables of linear and angular measurements were calculated from fourteen landmarks digitized on each radiograph as described in Figure 1 and Table 1. To evaluate the error of the method, 20 cephalograms were selected randomly and duplicate determinations were performed 4 weeks later by the same examiner. An intra-class correlation (ICC) coefficient was calculated to evaluate the intra-operator reliability. The values of all calculated intra-class correlation coefficients were greater than 0.95, showing repeated agreement with regard to all measurements.

Figure 1.

Landmarks of cephalometric analysis. Ba, basion; S, sella point; N, nasion; ANS, anterior nasal spine; PNS, posterior nasal spine; A, the deepest point in the concavity of the anterior maxilla between the anterior nasal spine and the alveolar crest; B, the deepest point in the concavity of the anterior mandible between the alveolar crest and pogonion; Pcd, the most posterosuperior point of the condylar head; Go, gonion; Gn, gnathion; Me, menton; Ptm, pterygomaxillary fissure point; Pog, pogonion; U1, upper incisors; L1, lower incisors; U6, the mesial buccal cusp of upper maxillary first molar; UL, upper lip; LL, lower lip; N’, nasion of soft tissue; Pog’, pogonion of soft tissue; Sn, subnasale.

Table 1.

Description of the cephalometric measurements.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

SPSS 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform the statistical analysis. Descriptive data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), median with interquartile range (IQR), or number (percentage), as appropriate. Whether the data were normally distributed was examined using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The independent t-test (for normally distributed variables) and non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test (for non-normally distributed variables) were used to compare the differences in the demographic characteristics between male and female subjects. Correlation coefficients were measured through the Pearson correlation analysis if the variables followed a normal distribution, while those that were not normally distributed were examined through the Spearman rank correlation analysis. Based on the univariate analyses, the correlation between the cephalometric variables and the severity of OSA was determined by multiple regression analysis. p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Sample size calculation was performed based on the study by Yu et al. [24]. In order to detect a correlation of 0.45 (−0.45) using a two-sided hypothesis test with a significance level of 0.05 and a power of 0.80, a number of 36 subjects would be needed for each group.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

A total of 112 adult participants (M/F = 67:45, mean age: 28.4 ± 7.29 years, age range: 18–52 years, mean male age: 28.8 ± 7.62 years, mean female age: 27.8 ± 6.79 years) were included in this study. The detailed demographic data of the patients are demonstrated in Table 2. The AHI value and the LSaO2 levels, along with 13 out of 39 cephalometric parameters were significantly different in the different gender groups. We further divided the participants into male and female groups to investigate whether gender differences affect the correlation between craniofacial parameters and OSA severity.

Table 2.

Demographic, polysomnographic, and cephalometric parameters.

3.2. Correlation Analysis Between Craniofacial Cephalometric Parameters and the Severity of OSA in All Subjects Regardless of Gender

In this study, we investigated the relations between cephalometric parameters and OSA severity indicators (the AHI and LSaO2) in all subjects regardless of gender. Regarding the AHI, SNA, SNB, PP-FH, U1-L1, U1-SN, L1-NB (°), and L1-Apo were the parameters with statistically significant correlations with the AHI. SNA, SNB, U1-SN, L1-NB (°), and L1-Apo were negatively correlated with the AHI, while PP-FH and U1-L1 were positively correlated with the AHI. Interestingly, none of the cephalometric parameters included in this study demonstrated statistically significant correlation with the LSaO2 in the whole sample (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation analysis between cephalometric parameters and AHI/LSaO2 in all subjects.

3.3. Correlation Analysis Between Craniofacial Cephalometric Parameters and the Severity of OSA in Male and Female Individuals

Based on the results above, we investigated whether there was a gender-dependent pattern of the cephalometric parameters associated with the AHI and LSaO2. In male individuals, only U1-L1 and U1-SN were the parameters with a statistically significant correlation with the AHI. Meanwhile, SNB, ANS-Me, L1-NB (°), and L1-Apo demonstrated a statistically significant correlation with the AHI in the female groups (Table 4). Regarding the LSaO2, U6-PP and N’-SN-Pog’ were identified as parameters with a statistically significant correlation in the male group. In the female group, SNB, ANB, NBa-PtGn, and U6-Ptm were statistically significant parameters (Table 5). As expected, all of the correlation coefficients in the male and female groups showed a similar trend to the whole sample regardless of gender (Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5).

Table 4.

Correlation analysis between cephalometric parameters and AHI in male and female subjects.

Table 5.

Correlation analysis between cephalometric parameters and LSaO2 in male and female subjects.

3.4. Multiple Regression Analysis Between Cephalometric Parameters and OSA Severity Indicators in the Male and Female Groups

Based on the results of the correlation analysis above, we selected the parameters that showed a strong correlation with the AHI and LSaO2 in both gender groups to perform a multiple regression analysis.

The multiple regression model was designed to predict the severity of OSA based on the cephalometric parameters. The AHI and LSaO2 were used as dependent variables to study the correlation between other independent variables. The VIF values between one and five of the variables indicated moderate multicollinearity between the variables and the AHI/LSaO2. Multivariate regression analysis demonstrated explanatory power for all models, with R2 values of 0.124 (male AHI), 0.218 (female AHI), 0.202 (male LSaO₂), and 0.469 (female LsaO2). All models showed statistical significance in the F-test (p < 0.05) (Table 6 and Table 7).

Table 6.

Multiple regression for cephalometric variables associated with AHI in male and female individuals.

Table 7.

Multiple regression for cephalometric variables associated with LSaO2 in male and female individuals.

4. Discussion

While the AHI has played a pivotal role in OSA classification, its limitations as a standalone diagnostic marker have become increasingly evident [25]. Emerging evidence highlights the need to integrate multidimensional metrics, such as hypoxia burden (e.g., T90, LSaO2), blood biomarkers, and genetic predictors, to refine OSA risk stratification [26]. Notably, nocturnal hypoxia severity demonstrates stronger associations with OSA-related comorbidities such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and systemic inflammation compared to the AHI alone [20,27,28]. Furthermore, pretreatment oxygen saturation levels correlate closely with therapeutic efficacy in improving oxygenation [29]. These findings advocate for combining the AHI with the LSaO2 and clinical assessments to optimize OSA diagnosis and personalized management.

As an effective tool to identify the risk of OSA, cephalometric analysis was often adopted to investigate the occurrence of OSA based on the AHI [30,31]. Its clinical utility lies in identifying craniofacial predictors of hypoxia susceptibility rather than replacing diagnostic sleep studies. Recent advances in AI-driven cephalometric analysis demonstrate remarkable reproducibility and diagnostic concordance with expert clinicians, potentially overcoming traditional limitations of manual tracing [32,33]. Such automated systems could enable standardized OSA risk stratification, even in primary care settings [34]. According to The American Association of Orthodontists (AAO) white paper on OSA and orthodontics, the strength of the relationship between craniofacial morphologies and the development of OSA is not well established [35]. It is also unclear as to whether the anatomic features of the craniofacial region can reflect the severity of nocturnal hypoxia. In this study, we explored the relations between morphological characteristics on a cephalogram and the severity of OSA based on both the AHI and LSaO2. As expected, there are several cephalometric parameters that showed a statistically significant correlation with the AHI and LSaO2, and the parameters were different in male and female groups.

In the correlation analysis for the whole sample, seven parameters correlated significantly with the AHI: five negatively (SNA, SNB, U1-SN, L1-NB°, L1-Apo) and two positively (PP-FH, U1-L1), while none of the cephalometric parameters showed a statistically significant correlation with the LSaO2. However, after dividing the subjects into different gender groups, we observed obvious changes in the parameters. Only U1-L1 and U1-SN were the parameters with a statistically significant correlation with the AHI in the male group, indicating that a more labial-inclined upper incisor position in relation to the lower incisors, and the SN line is related to a higher severity of OSA. In the female group, SNB, ANS-Me, L1-NB (°), and L1-Apo were all negatively correlated with the AHI (Table 4), suggesting that a more retruded mandible, a lower facial height, and less labial inclination of the lower incisors are associated with a higher severity of OSA.

Regarding the LSaO2, none of the parameters that significantly correlated with the AHI are associated with the LSaO2, and only U6-PP and N’-SN-Pog’ were identified as parameters with a statistically significant correlation in the male group. Based on the correlation coefficient value, a longer distance from the U6 to PP line and a larger N’-SN-Pog’ angle indicate a higher severity of OSA and risk of nocturnal hypoxia. In the female group, SNB, ANB, NBa-PtGn, and U6-Ptm were statistically significant parameters, with ANB being the only parameter that was negatively correlated with the LSaO2, suggesting that a more retruded and clockwise-rotated mandible, and a shorter distance from U6 to Ptm are associated with a higher risk of nocturnal hypoxia (Table 5). Interestingly, it has been observed that in patients with OSA without cardiovascular disease at baseline but who are followed up for a median duration of 78 months, the burden of hypoxia rather than the AHI predicted cardiovascular events and mortality after adjusting for confounding factors; notably stronger associations were observed in patients under 65 years and in women [36]. Our study also revealed that more cephalometric parameters exhibited associations with the LSaO2 in females compared to males; furthermore, the correlation levels between these parameters and the LSaO2 were also higher among females than males. These results implicate potential correlations between craniofacial morphology and the severity of OSA complications, along with a gender-dependent pattern.

Based on the correlation analysis mentioned above, we performed a multiple regression analysis to examine the viability of using cephalometric parameters to predict the values of the AHI and LSaO2. All of the regression models are statistically effective according to the F examination, but the level of correlation is relatively low. Notably, the level of correlation is significantly higher in the LSaO2 models than the AHI models, with almost twice the R2 value in the male and female groups, respectively. The results suggest that the cephalometric analysis is effective in assessing the LSaO2, and it is more reliable in predicting the severity of OSA based on the LSaO2 rather than the AHI. Regarding the gender difference, previous studies have shown that the prevalence and severity of OSA are described to be much higher in men, which could be related to sex hormones, changes in body fat distribution, neck circumference. and central ventilatory control [37,38]. It is quite interesting to find out that a gender-dependent pattern also applies to the cephalometric parameters related to the OSA severity in adult individuals. Further studies should investigate whether the difference in cephalometric parameters in male and female individuals contribute to the different clinical manifestations of OSA. In addition, the study population exhibited a younger mean age compared to prior OSA prevalence studies, which predominantly involved middle-aged and elderly cohorts [39]. This discrepancy may reflect sampling bias inherent to orthodontic clinics, where younger individuals disproportionately seek treatment. Therefore, caution should be exercised when extrapolating these findings to broader populations of patients with OSA.

An abnormality in craniofacial morphology is a crucial predisposing factor in the pathogenesis of OSA, which is often evaluated by cephalometric analysis by orthodontists [40,41]. However, according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s Clinical Practice Guideline, the physician specializing in sleep medicine is considered to be the primary healthcare provider with the highest qualification for diagnosing and treating patients with OSA [42,43]. Therefore, it appears that orthodontists fall outside of the scope of OSA diagnosis and management. In fact, since many patients with OSA seek orthodontic treatment for malocclusion, orthodontists can easily conduct early screening assessments for OSA [44]. By using lateral cephalograms, orthodontists can evaluate the patient’s craniofacial morphological features and assess the risk of OSA. In addition, when developing orthodontic treatment plans, orthodontists have a responsibility to consider how their interventions may impact the prognosis of OSA. While maxillomandibular advancement (MMA) surgery has proven to be the more successful surgical intervention for OSA, apart from tracheostomy, its association with orthognathic surgery and higher cost often discourage patient selection [45]. On the other hand, mandibular advancement devices (MADs) demonstrate efficacy for certain patients but are typically considered as a last-resort due to potential adverse effects. Other orthodontic treatments for OSA such as maxillary expansion either lack sufficient reliability or require long-term clinical follow-up [46,47]. Therefore, based on the results of this study and previous research, we suggest that orthodontists should pay more attention to cephalometric parameters related to the AHI and LSaO2. It is worth noting that cephalometric analysis only offers orthodontists and oral–maxillofacial surgeons a practical framework for the early identification of high-risk individuals since it is rooted in morphological assessment. If the cephalometric analysis indicates a higher risk of OSA, it is recommended that the patient consults a sleep specialist for further advice.

This investigation has several limitations. First, the sample consisted exclusively of Chinese patients with a relatively small cohort size. As a retrospective study design, our analysis was confined to pre-existing lateral cephalograms and polysomnography data, inherently limiting the inclusion of a control group or additional oximetric parameters (e.g., T90, oxygen desaturation index) that better quantify the hypoxemia burden. In addition, the potential impact of artifactually low LSaO2 values due to transient technical factors (e.g., oximeter displacement) could not be definitively ruled out in this retrospective analysis. Finally, several confounding variables, including body mass index and neck circumference, were not systematically controlled for due to incomplete medical records.

5. Conclusions

Several cephalometric parameters are related to the severity of OSA, as indicated by the AHI and LSaO2. Some of these parameters exhibit gender-specific differences. There is a significant difference between the parameters associated with the AHI and those associated with the LSaO2. Our analysis suggest that cephalometric parameters may exhibit gender-dependent associations with OSA severity, particularly when integrating the LSaO2 as a hypoxia-specific metric. While these findings highlight potential anatomical dimorphism in OSA pathophysiology, further validation in diverse cohorts is required before gender-specific cephalometric criteria can be implemented. Orthodontists should interpret these trends cautiously, prioritizing individualized risk assessment alongside polysomnographic evaluation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.D. and H.H.; methodology, Z.D.; software, Z.D.; validation, Z.D. and J.W.; investigation, Z.D. and L.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.D.; writing—review and editing, L.W. and H.H.; supervision, H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Hospital of Stomatology, Sun Yat-sen University (protocol code KQEC-2024-99-01. Date of approval: 20 June 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank the department of radiology at the Hospital of Stomatology, Sun Yat-sen University, for their assistance with cephalogram data management.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Patel, S.R. Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 171, itc81–itc96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjafield, A.V.; Ayas, N.T.; Eastwood, P.R.; Heinzer, R.; Ip, M.S.M.; Morrell, M.J.; Nunez, C.M.; Patel, S.R.; Penzel, T.; Pépin, J.L.; et al. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: A literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019, 7, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Lawati, N.M.; Patel, S.R.; Ayas, N.T. Epidemiology, risk factors, and consequences of obstructive sleep apnea and short sleep duration. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2009, 51, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusdottir, S.; Hill, E.A. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) among preschool aged children in the general population: A systematic review. Sleep. Med. Rev. 2024, 73, 101871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouahchi, Y.; Mejbri, M.; Mediouni, A.; Hedhli, A.; Ouahchi, I.; El Euch, M.; Toujani, S.; Dhahri, B. The Resolution of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in a Patient with Goiter after Total Thyroidectomy: A Case Report. Reports 2024, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Mendoza, J.; He, F.; Calhoun, S.L.; Vgontzas, A.N.; Liao, D.; Bixler, E.O. Association of Pediatric Obstructive Sleep Apnea with Elevated Blood Pressure and Orthostatic Hypertension in Adolescence. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 6, 1144–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.L.; Gozal, D.; Hunter, S.J.; Philby, M.F.; Kaylegian, J.; Kheirandish-Gozal, L. Impact of sleep disordered breathing on behaviour among elementary school-aged children: A cross-sectional analysis of a large community-based sample. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 48, 1631–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévy, P.; Kohler, M.; McNicholas, W.T.; Barbé, F.; McEvoy, R.D.; Somers, V.K.; Lavie, L.; Pépin, J.L. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeghiazarians, Y.; Jneid, H.; Tietjens, J.R.; Redline, S.; Brown, D.L.; El-Sherif, N.; Mehra, R.; Bozkurt, B.; Ndumele, C.E.; Somers, V.K. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 144, e56–e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, R.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, N.; Wang, X.; He, Y.; Yue, H.; Yin, Q. Pathophysiological mechanisms and therapeutic approaches in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randerath, W.; Verbraecken, J.; de Raaff, C.A.L.; Hedner, J.; Herkenrath, S.; Hohenhorst, W.; Jakob, T.; Marrone, O.; Marklund, M.; McNicholas, W.T.; et al. European Respiratory Society guideline on non-CPAP therapies for obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2021, 30, 210200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, J.H.; Park, J.W.; Jang, J.H.; Chung, J.W. Hyoid bone position as an indicator of severe obstructive sleep apnea. BMC Pulm. Med. 2022, 22, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armalaite, J.; Lopatiene, K. Lateral teleradiography of the head as a diagnostic tool used to predict obstructive sleep apnea. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2016, 45, 20150085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorelli, L.; Patcas, R.; Peltomäki, T.; Schätzle, M. Radiation dose of cone-beam computed tomography compared to conventional radiographs in orthodontics. J. Orofac. Orthop. 2016, 77, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelapu, B.C.; Kharbanda, O.P.; Sardana, H.K.; Balachandran, R.; Sardana, V.; Kapoor, P.; Gupta, A.; Vasamsetti, S. Craniofacial and upper airway morphology in adult obstructive sleep apnea patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cephalometric studies. Sleep. Med. Rev. 2017, 31, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finke, H.; Drews, A.; Engel, C.; Koos, B. Craniofacial risk factors for obstructive sleep apnea-systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sleep. Res. 2024, 33, e14004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, D.J.; Punjabi, N.M. Diagnosis and Management of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Review. Jama 2020, 323, 1389–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediano, O.; Barceló, A.; de la Peña, M.; Gozal, D.; Agustí, A.; Barbé, F. Daytime sleepiness and polysomnographic variables in sleep apnoea patients. Eur. Respir. J. 2007, 30, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, K.; Takata, Y.; Usui, Y.; Shiina, K.; Hashimura, Y.; Kato, K.; Saruhara, H.; Yamashina, A. New index for analysis of polysomnography, ‘integrated area of desaturation’, is associated with high cardiovascular risk in patients with mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea. Respiration 2009, 78, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wei, D.H.; Zhang, J.; Cao, J. Time Under 90% Oxygen Saturation and Systemic Hypertension in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Nat. Sci. Sleep. 2022, 14, 2123–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pae, E.K.; Lowe, A.A.; Sasaki, K.; Price, C.; Tsuchiya, M.; Fleetham, J.A. A cephalometric and electromyographic study of upper airway structures in the upright and supine positions. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 1994, 106, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, R.L.M.; Magalhães-da-Silveira, F.J.; Gozal, D. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea: Comparing the American Academy of Sleep Medicine proposed criteria with the STOP-Bang, NoSAS, and GOAL instruments. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 2023, 19, 1239–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F.; Guo, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, Y.; Cheng, F.; Quan, S.; Feng, Q.; Li, J. Artificial intelligence system for automated landmark localization and analysis of cephalometry. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2023, 52, 20220081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Fujimoto, K.; Urushibata, K.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Kubo, K. Cephalometric analysis in obese and nonobese patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest 2003, 124, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pevernagie, D.A.; Gnidovec-Strazisar, B.; Grote, L.; Heinzer, R.; McNicholas, W.T.; Penzel, T.; Randerath, W.; Schiza, S.; Verbraecken, J.; Arnardottir, E.S. On the rise and fall of the apnea-hypopnea index: A historical review and critical appraisal. J. Sleep. Res. 2020, 29, e13066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, A.; Ayappa, I.; Ayas, N.; Collop, N.; Kirsch, D.; McArdle, N.; Mehra, R.; Pack, A.I.; Punjabi, N.; White, D.P.; et al. Metrics of sleep apnea severity: Beyond the apnea-hypopnea index. Sleep. 2021, 44, zsab030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabryelska, A.; Chrzanowski, J.; Sochal, M.; Kaczmarski, P.; Turkiewicz, S.; Ditmer, M.; Karuga, F.F.; Czupryniak, L.; Białasiewicz, P. Nocturnal Oxygen Saturation Parameters as Independent Risk Factors for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus among Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, E.R.; Pires, G.N.; Andersen, M.L.; Tufik, S.; Rosa, D.S. Oxygen saturation as a predictor of inflammation in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2022, 26, 1613–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Almeida, F.R. Disparities in oxygen saturation and hypoxic burden levels in obstructive sleep apnoea patient’s response to oral appliance treatment. J. Oral. Rehabil. 2022, 49, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, N.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Guo, J. Craniofacial and upper airway morphological characteristics associated with the presence and severity of obstructive sleep apnea in Chinese children. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1124610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johal, A.; Conaghan, C. Maxillary morphology in obstructive sleep apnea: A cephalometric and model study. Angle Orthod. 2004, 74, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schwendicke, F.; Chaurasia, A.; Arsiwala, L.; Lee, J.H.; Elhennawy, K.; Jost-Brinkmann, P.G.; Demarco, F.; Krois, J. Deep learning for cephalometric landmark detection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2021, 25, 4299–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, H.W.; Park, J.H.; Moon, J.H.; Yu, Y.; Kim, H.; Her, S.B.; Srinivasan, G.; Aljanabi, M.N.A.; Donatelli, R.E.; Lee, S.J. Automated identification of cephalometric landmarks: Part 2-Might it be better than human? Angle Orthod. 2020, 90, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadek, M.; Alaskari, O.; Hamdan, A. Accuracy of web-based automated versus digital manual cephalometric landmark identification. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2024, 28, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrents, R.G.; Shelgikar, A.V.; Conley, R.S.; Flores-Mir, C.; Hans, M.; Levine, M.; McNamara, J.A.; Palomo, J.M.; Pliska, B.; Stockstill, J.W.; et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and orthodontics: An American Association of Orthodontists White Paper. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2019, 156, 13–28.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzepizur, W.; Blanchard, M.; Ganem, T.; Balusson, F.; Feuilloy, M.; Girault, J.M.; Meslier, N.; Oger, E.; Paris, A.; Pigeanne, T.; et al. Sleep Apnea-Specific Hypoxic Burden, Symptom Subtypes, and Risk of Cardiovascular Events and All-Cause Mortality. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 205, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bixler, E.O.; Vgontzas, A.N.; Lin, H.M.; Ten Have, T.; Rein, J.; Vela-Bueno, A.; Kales, A. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in women: Effects of gender. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 163, 608–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.T.; Wang, H.M.; Lai, H.L. Gender differences in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2016, 33, e9–e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senaratna, C.V.; Perret, J.L.; Lodge, C.J.; Lowe, A.J.; Campbell, B.E.; Matheson, M.C.; Hamilton, G.S.; Dharmage, S.C. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in the general population: A systematic review. Sleep. Med. Rev. 2017, 34, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Gao, X. The interaction of obesity and craniofacial deformity in obstructive sleep apnea. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2021, 50, 20200425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.H.; Jeon, J.Y.; Jang, K.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, K.R.; Ryu, S.; Hwang, K.G. Gender-specific cephalometric features related to obesity in sleep apnea patients: Trilogy of soft palate-mandible-hyoid bone. Maxillofac. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 41, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, S.P.; Ayappa, I.A.; Caples, S.M.; Kimoff, R.J.; Patel, S.R.; Harrod, C.G. Treatment of Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea with Positive Airway Pressure: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 2019, 15, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapur, V.K.; Auckley, D.H.; Chowdhuri, S.; Kuhlmann, D.C.; Mehra, R.; Ramar, K.; Harrod, C.G. Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnostic Testing for Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 2017, 13, 479–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons-Coleman, M.; Bates, C.; Barber, S. Obstructive sleep apnoea and the role of the dental team. Br. Dent. J. 2020, 228, 681–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicus Brookes, C.C.; Boyd, S.B. Controversies in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Surgery. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 29, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamoda, M.M.; Kohzuka, Y.; Almeida, F.R. Oral Appliances for the Management of OSA: An Updated Review of the Literature. Chest 2018, 153, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Zhang, L.; Lu, Y. The role of rapid maxillary expansion in pediatric obstructive sleep apnea: Efficacy, mechanism and multidisciplinary collaboration. Sleep. Med. Rev. 2023, 67, 101733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).