Cardiovascular Disease and All-Cause Mortality Among Individuals with Low Sexual Frequency

Abstract

1. Introduction

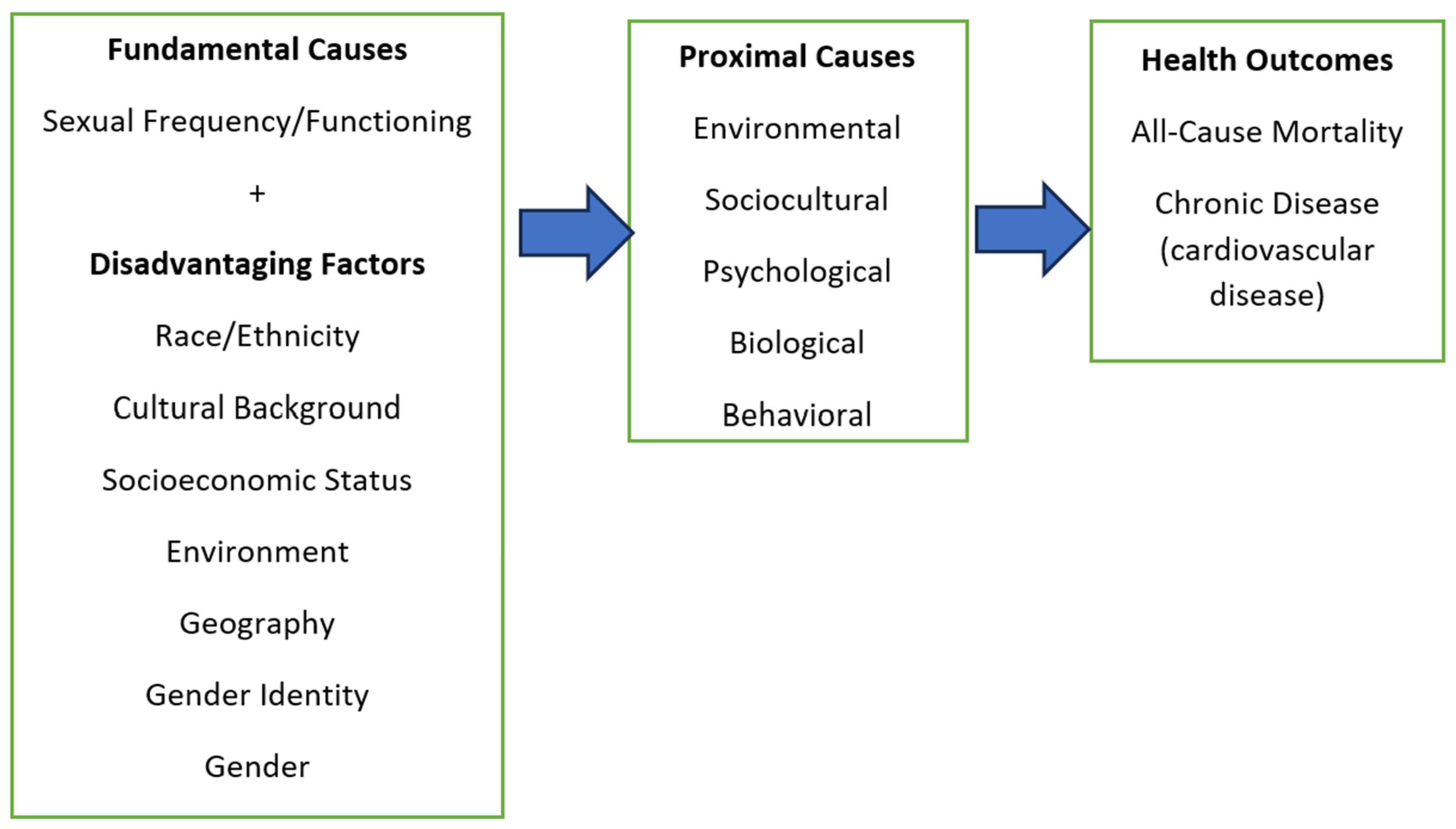

Fundamental Cause Theory

2. Methods

2.1. All-Cause Mortality

2.2. CDC Mortality Linkage

2.2.1. Measures: Cardiovascular Disease (CVD)

- Congestive heart failure—“Has a doctor or other health professional ever diagnosed you with congestive heart failure?”

- Coronary heart disease—“Has a doctor or other health professional ever diagnosed you with coronary heart disease?”

- Angina (angina pectoris)—“Has a doctor or other health professional ever diagnosed you with angina?”

- Heart attack (myocardial infarction)—“Has a doctor or other health professional ever diagnosed you with a heart attack?”

- Stroke—“Has a doctor or other health professional ever diagnosed you with a stroke?”

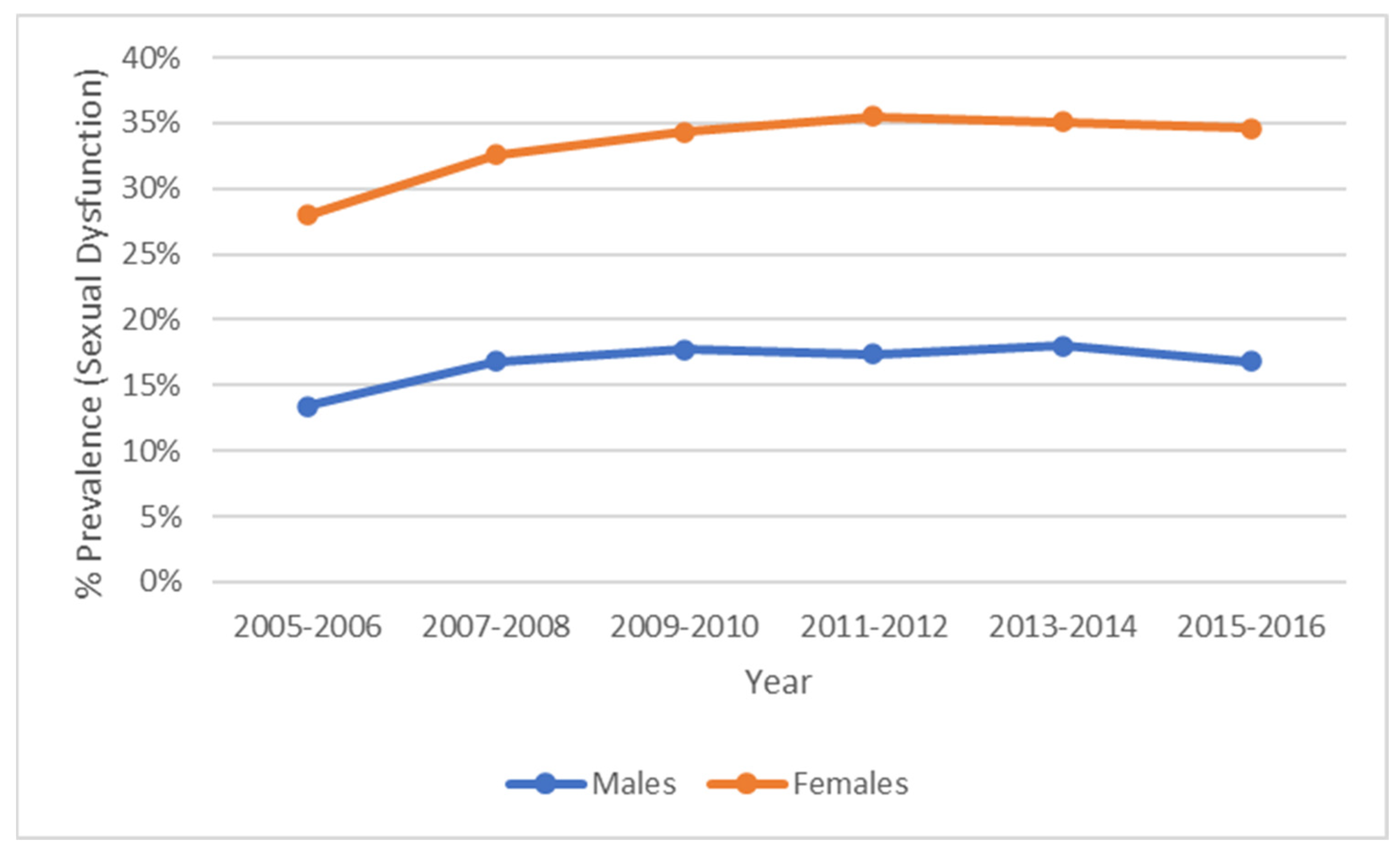

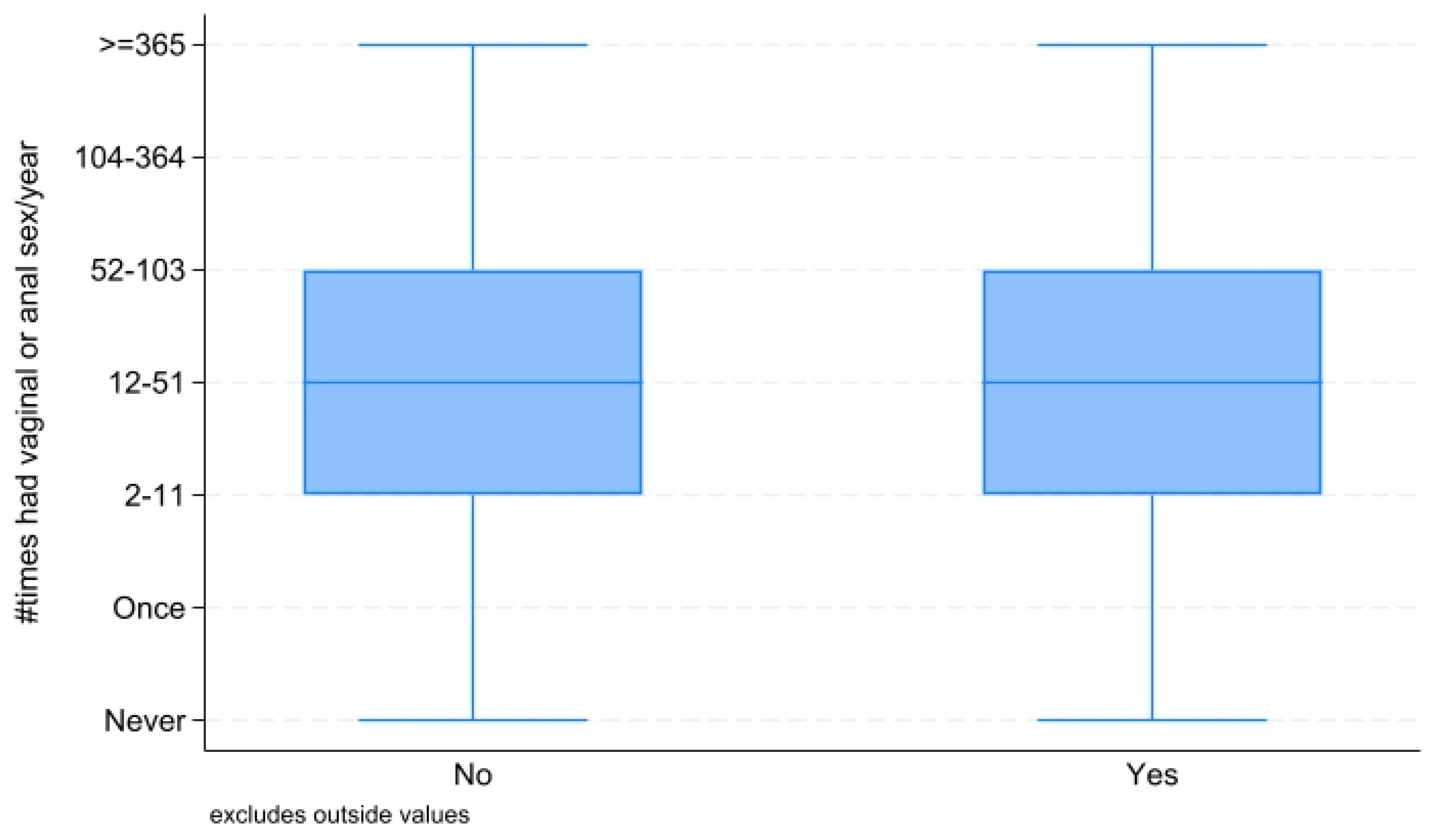

2.2.2. Measures: Sexual Frequency and Sexual Dysfunction

2.2.3. Measures: Obesity

2.2.4. Measures: Diabetes

2.2.5. Measures: Smoking Status

2.2.6. Measures: Additional Covariates

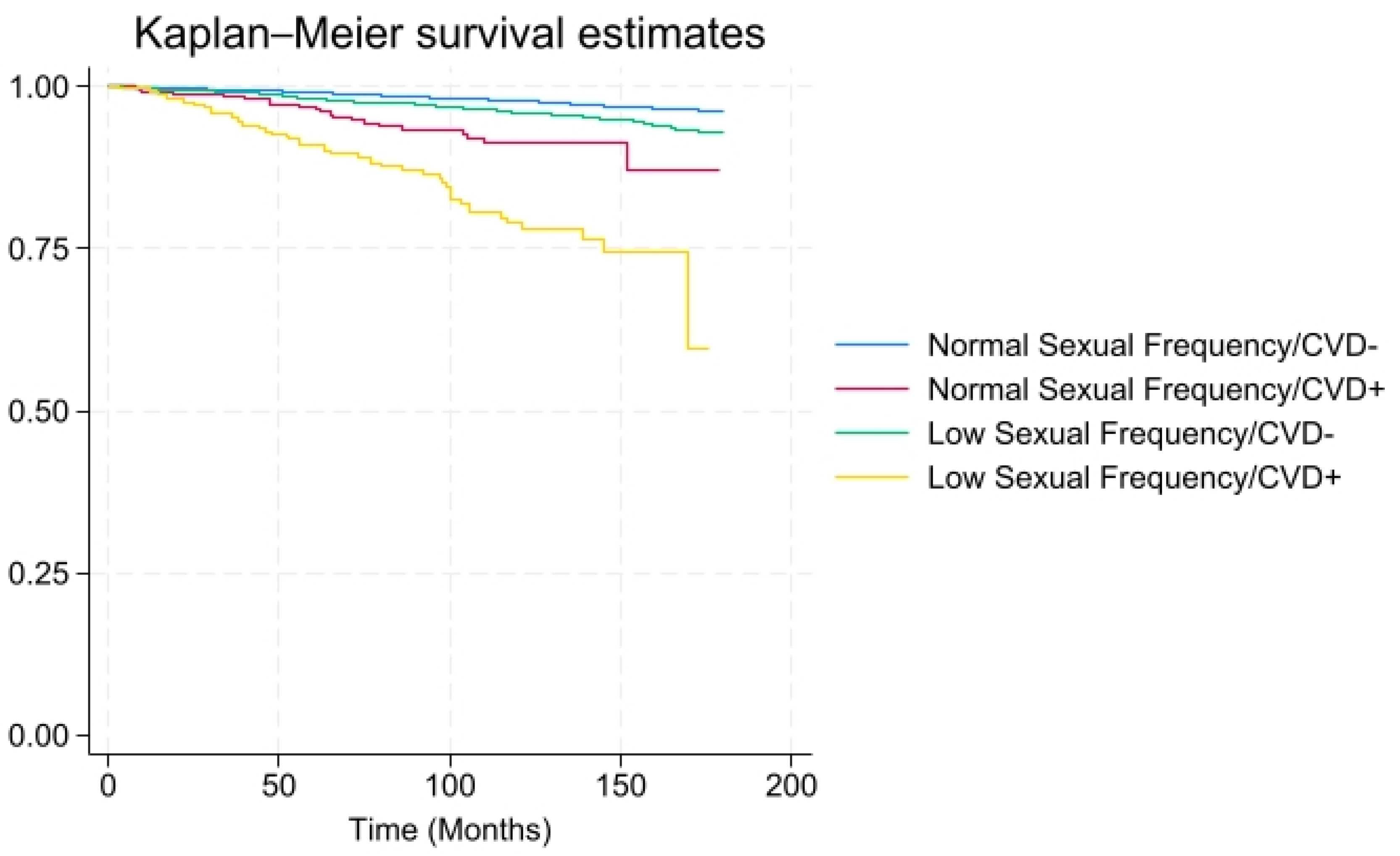

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Recommendations

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ueda, P.; Mercer, C.H.; Ghaznavi, C.; Herbenick, D. Trends in frequency of sexual activity and number of sexual partners among adults aged 18 to 44 years in the US, 2000–2018. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, K.R.; Bierman, A. Risk or release?: Porn use trajectories and the accumulation of sexual partners. Soc. Curr. 2018, 5, 566–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Sherman, R.A.; Wells, B.E. Sexual inactivity during young adulthood is more common among US Millennials and iGen: Age, period, and cohort effects on having no sexual partners after age 18. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2017, 46, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, N.; Malic, V.; Fu, T.-C.; Paul, B.; Zhou, Y.; Dodge, B.; Fortenberry, J.D.; Herbenick, D. Porn sex versus real sex: Sexual behaviors reported by a U.S. probability survey compared to depictions of sex in mainstream internet-based male–female pornography. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2022, 51, 1187–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Calvo, J.; Giménez-García, C.; Gil-Llario, M.D.; Ballester-Arnal, R. Motives to engage in online sexual activities and their links to excessive and problematic use: A systematic review. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2018, 5, 491–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kislev, E. The sexual activity and sexual satisfaction of singles in the second demographic transition. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2020, 18, 726–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Diseases. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Gerber, Y.; Weinstein, R.; Drory, Y. Resuming sexual activity soon after heart attack linked with improved survival. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2024, 31, 780–790. [Google Scholar]

- Gianotten, W.L.; Alley, J.C.; Diamond, L.M. The health benefits of sexual expression. Int. J. Sex. Health 2021, 33, 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.D.; Frankel, S.; Yarnell, J. Sex and death: Are they related? Findings from the Caerphilly Cohort Study. BMJ 1997, 315, 1641–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, L.K.; Blazer, D.G.; Hughes, D.C.; Fowler, N. Sexual activity and cardiovascular health: A study from the Duke University population. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2001, 42, 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Corona, G.; Lee, D.M.; Forti, G.; O’Connor, D.B.; Maggi, M.; Wu, F.C.W. Sexual activity and cardiovascular health in men: Results from the European Male Ageing Study (EMAS). Int. J. Androl. 2010, 33, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland, D.L.; Morrow, A.L.; Hamilton, B.D.; Hevesi, K. Do pornography use and masturbation frequency play a role in delayed/inhibited ejaculation during partnered sex? A comprehensive and detailed analysis. Sexes 2022, 3, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.Y.; Wilson, G.; Berger, J.; Christman, M.; Reina, B.; Bishop, F.; Klam, W.P.; Doan, A.P. Is internet pornography causing sexual dysfunctions? a review with clinical reports. Behav. Sci. 2016, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P.; Behrens, I.; Honigberg, M.C. Sex-specific risk factors in cardiovascular disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1489728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hippisley-Cox, J.; Coupland, C.; Brindle, P. Development and validation of QRISK3 risk prediction algorithms to estimate future risk of cardiovascular disease: Prospective cohort study. BMJ 2017, 357, j2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greear, G.M.; Garg, N.; Hsieh, T.-C. Male Sexual Health and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr. Sex. Health Rep. 2020, 12, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Anderson, P.; Davis, W.S. Connection Between Depression, Sexual Frequency, and All-cause Mortality: Findings from a Nationally Representative Study. J. Psychosexual Health 2024, 6, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.F.; Chawla, I.; Goel, K.; Gollen, R.; Singh, R. Impact of obesity on female sexual dysfunction: A remiss. Curr. Women’s Health Rev. 2021, 17, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennanen-Iire, C.; Prereira-Lourenço, M.; Padoa, A.; Ribeirinho, A.; Samico, A.; Gressler, M.; Jatoi, N.A.; Mehrad, M.; Girard, A. Sexual health implications of COVID-19 pandemic. Sex. Med. Rev. 2021, 9, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Gao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X. Associations between sexual activity frequency and depression in women: Insights from the NHANES data. J. Sex. Med. 2024, 22, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Link, B.G.; Phelan, J.C. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J. Health Soc. Behav. (Extra Issue) 1995, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouston, S.A.; Link, B.G. A retrospective on fundamental cause theory: State of the literature and goals for the future. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2021, 47, 131–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rydland, H.T.; Solheim, E.F.; Eikemo, T.A. Educational inequalities in high- vs. low-preventable health conditions: Exploring the fundamental cause theory. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 267, 113145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, G.M.; He, H.M.; Lai, M.M.; Li, X.M.; Chen, Y.M.; Wei, B. Systemic immune-inflammatory index and its association with female sexual dysfunction, specifically low sexual frequency, in depressive patients: Results from NHANES 2005 to 2016. Medicine 2024, 103, e38151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Xu, M.; Liao, Y.; Zhou, H.; Ma, H.; Geng, Q. Temporal Trends and Differences in Sexuality Among Depressed and Non-Depressed Adults in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 14010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, W.S.; Banerjee, S.; Anderson, P. Inflammation, C-reactive protein Level, Sexual Frequency, and Mortality. ResearchSquare 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P.; Loscalzo, J.; Ridker, P.M.; Fuster, V.; Rosenzweig, A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 1376–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Fuster, V.; Zoghbi, W.A. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risks. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–2991. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, A.H.; Althof, S.E.; McCabe, M.P. Sexual dysfunction and antidepressants: A review of the literature. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2016, 18, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Griggs, R.C.; Seligman, H.K.; Thompson, A. The impact of medications on sexual function in women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 217, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jackson, G.; Montorsi, P.; Burnett, A.L. Management of erectile dysfunction: Current treatment options. Lancet 2013, 381, 2361–2371. [Google Scholar]

- Glover, J.; Wheeler, K.; Jones, M. Impact of psychotropic medications on sexual function. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 39, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, A.; Houghton, L.; Singer, L. Hormonal therapies and sexual function. J. Sex. Med. 2018, 15, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoutsos, S.; Kotsis, V. Erectile dysfunction and its correlation with arterial hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. J. Atheroscler. Prev. Treat. 2023, 14, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, J.D.; McMahon, C.G.; Guay, A.T.; Morgentaler, A.; Althof, S.E.; Becher, E.F.; Bivalacqua, T.J.; Burnett, A.L.; Buvat, J.; El Meliegy, A.; et al. The International Society for Sexual Medicine’s process of care for the assessment and management of testosterone deficiency in adult men. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 1660–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bivalacqua, T.J.; Musicki, B.; Burnett, A.L. Erectile dysfunction: Vascular mechanisms and new treatment targets. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2021, 18, 100–118. [Google Scholar]

- Ganz, P.; Hays, R.D.; Mangione, C.M.; Vitagliano, A. Erectile dysfunction as an early marker of vascular dysfunction. Am. J. Med. 2023, 136, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsberg, S.A.; Clayton, A.H. The female sexual response: New perspectives on desire and arousal. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. 2015, 42, 669–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meston, C.M.; Rellini, A.H.; Telch, M.J. Female sexual dysfunction in clinical settings: Management and challenges. Annu. Rev. Sex Res. 2020, 15, 24–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, W.S.; Lin, H.H.; Kao, C.H. The relationship between cardiovascular diseases and erectile dysfunction: A nationwide population-based study. Medicine 2018, 97, e9719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannas, D.; Frizza, F.; Vignozzi, L.; Corona, G.; Maggi, M.; Rastrelli, G. Erectile dysfunction is a hallmark of cardiovascular disease: Unavoidable matter of fact or opportunity to improve men’s health? J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Total Population (n = 10,596) | Low Sexual Frequency (Less Than Once a Month) (n = 4840) | Moderate-to-High/High Sexual Frequency (Once a Month or More) (n = 5756) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CVD (%) ** | 3.1 (2.8–3.5) | 4.9 (4.3–5.6) | 2.4 (2.1–2.8) |

| Smoking Status (%) ** | |||

| Never Smoked | 64.9 (63.5–36.6) | 63.0 (61.3–64.8) | 65.7 (64.1–67.3) |

| Formerly Smoked | 19.4 (18.5–20.2) | 19.9 (18.6–21.2) | 19.1 (18.1–20.2) |

| Currently Smoke | 15.7 (14.7–16.7) | 17.1 (15.7–18.5) | 15.1 (14.1–16.2) |

| Hypertension (%) ** | 21.5 (20.4–22.6) | 25.4 (23.7–27.20 | 19.9 (18.8–21.1) |

| Diabetes (%) ** | 6.4 (5.9–7.0) | 9.3 (8.2–10.4) | 5.3 (4.8–5.9) |

| Age (SE) ** | 38.5 (0.20) | 41.7 (0.27) | 36.1 (0.22) |

| Gender Male (%) | 50.3 (49.5–51.1) | 51.5 (49.9–53.1) | 49.8 (48.9–50.8) |

| Marital Status (%) ** | |||

| Married | 58.7 (56.9–60.5) | 50.0 (47.052.3) | 62.2 (60.5–64.0) |

| Widowed | 0.7 (0.5–0.8) | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) |

| Divorced | 8.1 (7.5–8.7) | 11.6 (10.3–12.9) | 6.7 (6.1–7.3) |

| Separated | 2.4 (2.1–2.8) | 3.3 (2.8–3.9) | 2.1 (1.7–2.5) |

| Never Married | 19.1 (17.5–20.6) | 25.9 (23.7–28.2) | 16.4 (14.9–17.8) |

| Living with Partner | 11.1 (10.3–11.9) | 8.2 (7.2–9.2) | 12.3 (11.3–13.2) |

| Ethnicity (%) ** | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 66.5 (63.6–69.4) | 62.4 (59.0–65.7) | 68.1 (65.2–71.0) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 11.5 (10.0–13.0) | 15.0 (13.0–17.0) | 10.1 (8.7–11.5) |

| Hispanic | 15.2 (13.1–17.3) | 16.1 (13/9–18.3) | 14.8 (12.6–17.0) |

| Other | 6.9 (6.2–7.6) | 6.5 (5.5–7.7) | 7.0 (6.3–7.8) |

| Education Level (%) ** | |||

| Some High School | 15.1 (13.6–16.5) | 18.4 (16.3–20.6) | 13.7 (12.4–15.1) |

| High School Graduate | 21.3 (20.0–22.6) | 22.7 (20.9–24.5) | 20.8 (19.3–22.2) |

| Some College and Beyond | 63.6 (61.3–65.9) | 58.9 (55.8–61.9) | 65.5 (63.2–67.7) |

| PIR < 1 ** | 14.2 (12.9–15.4) | 17.0 (15.3–18.7) | 13.1 (11.8–14.2) |

| All deaths (N, %) ** | (2.6%) 448 | (4.0%) 210 | (2.0%) 238 |

| Total Population HR (95%CI) | CVD- Low Sexual Frequency HR (95%CI) | CVD+ Moderate-to-High/High Sexual Frequency HR (95%CI) | CVD+ Low Sexual Frequency HR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVD/Sexual Frequency | 1.73 (1.08–2.76) * | 1.06 (0.81–1.40) | 1.21 (0.60–2.43) | 2.26 (1.20–4.26) * |

| Smoking Status | ||||

| Never Smoked | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Formerly Smoked | 1.21 (0.82–1.77) | 1.11 (0.71–1.72) | 1.13 (0.72–1.77) | 1.42 (0.79–2.56) |

| Currently Smoke | 2.88 (2.14–3.87) ** | 3.06 (2.19–4.27) ** | 3.23 (2.16–4.83) ** | 2.47 (1.56–3.92) ** |

| Obesity | 1.10 (0.85–1.42) | 1.17 (0.89–1.54) | 1.07(0.76–1.51) | 1.16(0.71–1.89) |

| Hypertension | 1.62 (1.20–2.20) ** | 1.65 (1.19–2.28) ** | 1.73(1.12–2.67) * | 1.44(0.93–2.24) |

| Diabetes | 1.69 (1.21–2.37) ** | 1.69 (1.16–2.45) ** | 1.52(0.91–2.54) | 1.77(1.17–2.68) ** |

| Age | 1.06 (1.05–1.08) ** | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) ** | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) ** | 1.07 (1.04–1.09) ** |

| Gender (ref. female) | 1.41 (1.11–1.80) ** | 1.40 (1.08–1.81) * | 1.35 (0.96–1.89) | 1.57 (1.08–2.28) * |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Widowed | 0.94 (0.43–2.03) | 0.70 (0.27–1.85) | 0.39 (0.05–2.75) | 1.11 (0.50–2.46) |

| Divorced | 1.55 (1.04–2.31) * | 1.52 (1.01–2.29) * | 1.34 (0.71–2.53) | 1.70 (0.96–2.99) |

| Separated | 2.24 (1.16–4.30) * | 2.15 (1.05–4.43) * | 2.44 (1.10–5.41) * | 1.95 (0.74–5.15) |

| Never Married | 2.08 (1.40–3.10) ** | 2.12 (1.40–3.22) ** | 2.14 (1.29–3.56) ** | 1.90 (1.11–3.27) * |

| Living with partner | 1.79 (1.16–2.76) ** | 1.77 (1.11–2.82) * | 1.82 (1.04–3.21) * | 1.69 (0.91–3.13) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.07 (0.84–1.36) | 1.08 (0.84–1.38) | 1.46 (0.99–2.15) | 0.72 (0.49–1.05) |

| Hispanic | 0.64 (0.47–0.87) ** | 0.61 (0.43–0.85) ** | 0.74 (0.47–1.15) | 0.53 (0.35–0.80) ** |

| Other | 0.48 (0.23–0.99) * | 0.51 (0.24–1.12) | 0.44 (0.15 = 1.30) | 0.51 (0.19–1.39) |

| Education Level | ||||

| Some College or Beyond | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Some High School | 0.67 (0.47–0.96) * | 0.61 (0.40–0.92) * | 0.66 (0.39–1.11) | 0.72 (0.45–1.15) |

| High School Graduate | 0.67 (0.50–0.90) ** | 0.60 (0.43–0.82) ** | 0.67 (0.43–1.0–3) | 0.71 (0.47–1.06) |

| PIR < 1 | 1.58 (1.13–2.21) ** | 1.52 (1.04–2.22) * | 1.33 (0.86–2.05) | 1.94 (1.15–3.26) * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Davis, W.S.; Anderson, P.; Banerjee, S. Cardiovascular Disease and All-Cause Mortality Among Individuals with Low Sexual Frequency. Healthcare 2025, 13, 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050461

Davis WS, Anderson P, Banerjee S. Cardiovascular Disease and All-Cause Mortality Among Individuals with Low Sexual Frequency. Healthcare. 2025; 13(5):461. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050461

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavis, W. Sumner, Peter Anderson, and Sri Banerjee. 2025. "Cardiovascular Disease and All-Cause Mortality Among Individuals with Low Sexual Frequency" Healthcare 13, no. 5: 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050461

APA StyleDavis, W. S., Anderson, P., & Banerjee, S. (2025). Cardiovascular Disease and All-Cause Mortality Among Individuals with Low Sexual Frequency. Healthcare, 13(5), 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13050461