Abstract

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and telemedicine are transforming healthcare delivery, particularly in rural and underserved communities. Background/Objectives: The purpose of this systematic review is to explore the use of AI-driven diagnostic tools and telemedicine platforms to identify underlying themes (constructs) in the literature across multiple research studies. Method: The research team conducted an extensive review of studies and articles using multiple research databases that aimed to identify consistent themes and patterns across the literature. Results: Five underlying constructs were identified with regard to the utilization of AI and telemedicine on patient diagnosis in rural communities: (1) Challenges/benefits of AI and telemedicine in rural communities, (2) Integration of telemedicine and AI in diagnosis and patient monitoring, (3) Future considerations of AI and telemedicine in rural communities, (4) Application of AI for accurate and early diagnosis of diseases through various digital tools, and (5) Insights into the future directions and potential innovations in AI and telemedicine specifically geared towards enhancing healthcare delivery in rural communities. Conclusions: While AI technologies offer enhanced diagnostic capabilities by processing vast datasets of medical records, imaging, and patient histories, leading to earlier and more accurate diagnoses, telemedicine acts as a bridge between patients in remote areas and specialized healthcare providers, offering timely access to consultations, follow-up care, and chronic disease management. Therefore, the integration of AI with telemedicine allows for real-time decision support, improving clinical outcomes by providing data-driven insights during virtual consultations. However, challenges remain, including ensuring equitable access to these technologies, addressing digital literacy gaps, and managing the ethical implications of AI-driven decisions. Despite these hurdles, AI and telemedicine hold significant promise in reducing healthcare disparities and advancing the quality of care in rural settings, potentially leading to improved long-term health outcomes for underserved populations.

Keywords:

artificial intelligence; AI; telemedicine; telehealth; rural healthcare; quality; outcomes 1. Introduction

Access to quality healthcare remains a persistent challenge for rural communities due to geographic isolation, limited healthcare infrastructure, and shortages of medical professionals, all of which contribute to disparities in health outcomes. These challenges have driven innovation in healthcare delivery, with artificial intelligence (AI) and telemedicine emerging as transformative solutions to address these issues [1]. Both technologies have the potential to bridge gaps in care, enhance diagnostic precision, and improve patient outcomes; however, a deeper understanding of their effectiveness and impact on rural populations is needed.

AI has revolutionized various aspects of healthcare by enabling predictive analytics, personalized treatment plans, and streamlined clinical workflows [2]. Machine learning algorithms support early disease detection, while AI-powered decision support systems assist healthcare providers in optimizing the quality of care. Similarly, telemedicine—through virtual consultations, remote monitoring, and telehealth platforms—has expanded access to essential medical services, minimizing the need for travel and ensuring continuity of care for patients in underserved areas [1,3].

Despite their potential, the adoption of AI and telemedicine in rural settings faces several challenges, including limited broadband access, digital literacy barriers, and concerns about data privacy. Furthermore, evidence regarding their direct impact on healthcare quality—such as clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, and care delivery efficiency—remains fragmented across various studies and contexts [3]. To address these gaps, the research team initiated this review to explore the underlying constructs and themes in the existing literature on the application of AI and telemedicine in rural communities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview and Inclusion Criteria

This systematic review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA). This research team’s intent was to investigate how AI could be used to improve the quality of care that patients receive, and to determine the potential future applications of AI by analyzing the most recent literature published surrounding this topic. The literature obtained for this article was selected from three research databases (MEDLINE Complete, Complementary Index, and Academic Search Complete), all accessed through the Texas State University Alkek Library’s EBSCOhost search tool. These specific research databases were utilized in this review because of their availability to the researchers via the Texas State University Library’s EBSCOhost online platform, while yielding the highest number of initial number of articles identified that met the search parameters, but was not duplicative of other available databases. The search string was initially formulated using a brainstorming session among the research team members, each providing their input as to the key terms and themes related to the overall topic of AI and rural communities. Using this information, the team conducted several online Google Scholar search queries, identifying the opportunity to include quality of care in the rural healthcare setting as part of the current search.

Focusing specifically on ‘mhealth’ and related publications, the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) controlled vocabulary thesaurus (National Library of Medicine) was utilized to capture exploding terms for this topic, as well as ‘physical fitness’ and related terminology. Additional research team queries on the EBSCOhost website were conducted to ensure the highest number of published articles germane to the research topic were identified, using the most accessible Boolean search operators to identify the following search string for the study:

[(rural areas or rural communities or rural patients or rural population or remote) AND (telehealth or telemedicine or telemonitoring or telepractice or telenursing or telecare) AND (machine learning or artificial intelligence or deep learning or neural network) AND quality of care AND (diagnosis or diagnosing or diagnostics or assessment or screening)]

For an article to be included in this review, the article had to be published between 1 January 2020–31 December 2024 on the research database. The database queries carried out by the research team occurred from 2 to 28 February 2024. The 2024 ending search date range was automatically selected by EBSCO, the host website, and therefore, picked the most recent publications during the team’s search period. Other EBSCOhost search criteria included: Full Text, Peer Reviewed, and English Only. Full text articles are complete articles found online, as opposed to just the summary or abstract. To be considered peer reviewed, an article must undergo evaluation by experts in the field of study. Editorials, government reports, letters to editors, or other non-reviewed studies were also not included in the search.

Articles within the systematic review had to focus on or address the use of AI and/or telemedicine within rural communities, either as the primary research topic, or at least address how AI and/or telemedicine could improve quality of care. The team carried out a search for the most pertinent literature available to assess the use of AI and telemedicine in rural communities, both currently and potential future innovations. The information in the study did not include human subjects (secondary data sources), with all the literature being publicly available and published. If any study found by the team focused on any individual research subject(s), they were not identifiable to the team. Therefore, an institutional review board (IRB) review was not required, and obtaining consent was not necessary.

2.2. Exclusion Process

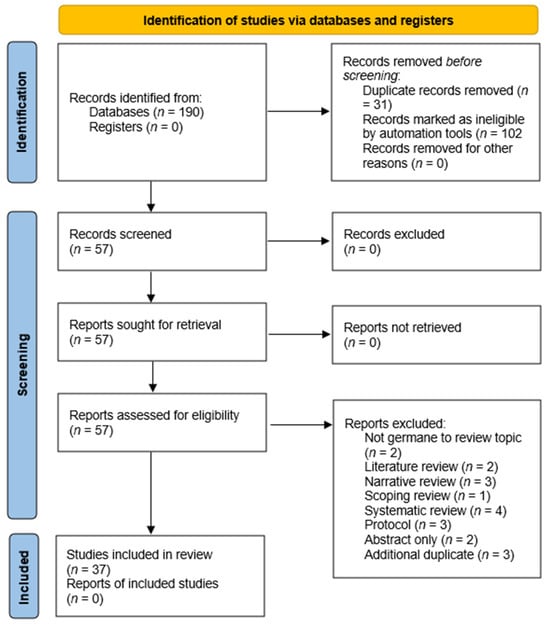

Figure 1 demonstrates the article exclusion process for the review. Figure 1 starts with our initial research database results and ends with our final literature sample (n = 57). Our initial search on EBSCOhost found 190 articles that fit our primary criteria; however, 31 articles were automatically removed from the search results by the EBSCOhost search engine, identified as duplicate articles. Additional articles were then removed from the search results because they were marked as ineligible by automation tools. Of these remaining articles in the EBSCOhost search results, 102 articles were excluded due to automation tools:

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) figure demonstrating the study selection process.

- 28 articles were removed for not being available in full text,

- 52 articles were removed for not being published in peer reviewed journals/outlets,

- 21 articles were removed because they were not published within the review’s prescribed date range.

The research team accessed all 57 articles for retrieval in full-text format for further analysis. Each article was reviewed by at least two of the research team’s members. Each member was assigned roughly 20 articles to review and determine if the articles were relevant to our literature review, and to see if any articles had slipped through our automated screening tools. Table 1 shows how all 57 articles were split up and assigned to each team member to review.

Table 1.

Reviewer assignment of the initial database search findings (full article review).

Upon completion of the full-text review, the research team collectively decided to exclude an additional 17 articles from the review. Two articles were identified as not germane to the current study’s review topic. Two articles were only available to the research team via the EBSCOhost platform as abstract only and three articles were study protocols. Three additional articles were identified as duplicates. Finally, 10 additional articles were removed from the review process for being classified by the review team as either a literature review, systematic review, narrative review, or a scoping review (Figure 1).

3. Results

Guided by the PRISMA protocols, the research team presented their initial article review findings by identifying each study’s population, intervention, control method(s), outcome(s), and study design as applicable. Further review of the articles by the research team involved assessing the articles for specific AI and telemedicine application, specifically in a rural health environment. Often, such articles included the delivery of care utilizing these resources in an ambulatory care/outpatient industry segment. Initial, individual article findings are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of findings (n = 37).

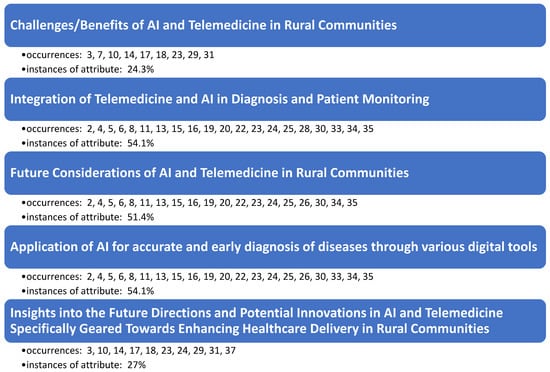

Results of the research team’s consensus meetings demonstrate five main themes (constructs) as identified in the literature to support the use of AI in rural communities. Findings are not mutually exclusive to only one specific theme, as several articles supported more than one construct upon review (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Occurrences of underlying themes as observed in the literature.

The systematic literature review findings reveal a significant focus on the integration and future implications of AI and telemedicine in rural communities, with these topics comprising the majority of the discussion. The construct “Challenges/Benefits of AI and Telemedicine in Rural Communities” was noted in 24.3% of the instances, underscoring both the potential advantages, such as improved access to healthcare, and the barriers, including technological limitations and resistance to adoption in rural settings. The most frequently addressed constructs, “Integration of Telemedicine and AI in Diagnosis and Patient Monitoring” and “Application of AI for Accurate and Early Diagnosis of Diseases through Various Digital Tools” independently accounted for 54.1% of the instances. This highlights the critical role of AI and telemedicine in enhancing diagnostic accuracy and enabling continuous patient monitoring in these areas. Finally, “Future Considerations of AI and Telemedicine in Rural Communities” appeared in 54.1% of the instances, emphasizing the importance of ongoing technological advancements and policy developments to fully realize the potential benefits of AI and telemedicine in rural healthcare.

4. Discussion

4.1. Challenges/Benefits of AI and Telemedicine in Rural Communities

Integrating AI and telemedicine into healthcare systems in rural or underdeveloped areas can drastically alter the healthcare landscape, though this transition is fraught with both significant challenges and profound benefits. Several barriers hinder the widespread adoption and effectiveness of telemedicine and AI. On one hand, regions like rural India face numerous practical obstacles, including insufficient technological infrastructure, intermittent power supply, limited internet access, and a lack of trained healthcare professionals, all of which are essential for the effective deployment of AI and telemedicine [18]. Limited access to high-speed internet and outdated technology infrastructure can impede the seamless delivery of virtual healthcare services. Additionally, the high costs associated with implementing advanced technologies can be prohibitive, limiting the spread of beneficial innovations [18]. Hypothesized barriers to telemedicine use include doctors’ beliefs that it may have little benefit, reduce revenue, and negatively impact their standing within the community [18]. Also, healthcare providers may need specialized training to effectively utilize telemedicine tools and AI technologies. Addressing these training needs is crucial to ensure that rural healthcare professionals can use the full potential of these innovations. Furthermore, data privacy and security present additional barriers to the adoption of telemedicine and AI in rural healthcare settings.

Benefits of integrating AI and telemedicine are substantial and multifaceted. One of the most notable advantages is the increased access to healthcare services, overcoming geographical barriers that often hinder rural residents from receiving timely medical attention. For instance, AI can greatly enhance the quality of care through improved diagnostic accuracy and personalized treatment plans, even in remote locations where specialized medical expertise is scarce [18]. Telemedicine extends healthcare’s reach, allowing patients in isolated areas to receive timely consultations, thus overcoming geographical barriers that traditionally impeded access to care [3,18]. Furthermore, telemedicine platforms can predict health status with maximum accuracy and facilitate continuous monitoring and management of chronic diseases, improving patient outcomes and reducing hospital visits [7,14,17]. Interactive telemedicine systems may include real-time communication between patients and healthcare providers, reduce travel time and ensure timely triage [10]. By combining telemedicine and AI, rural healthcare systems can leverage technology to bridge the gap in healthcare access and provide quality medical care to populations that have historically been underserved.

The deployment of AI in diagnostics and patient management systems can reduce the workload on the limited number of healthcare providers in rural settings, increasing efficiency and allowing more patients to be treated effectively [18]. AI applications in health data analysis can also predict outbreak patterns, which is crucial for preventive healthcare in underdeveloped regions.

Telemedicine and AI also offer economic benefits by reducing the need for physical infrastructure and decreasing travel times for both patients and healthcare providers. This not only lowers healthcare delivery costs but also improves the utilization of healthcare resources. Additionally, innovative applications like drone technology can facilitate the rapid delivery of medical supplies to remote areas, further bridging the gap in healthcare accessibility.

While the implementation of AI and telemedicine in rural or underdeveloped areas faces considerable challenges, the potential to significantly improve healthcare accessibility, quality, and efficiency holds immense promise. Overcoming these challenges requires targeted investments in infrastructure, training, and policy adjustments to ensure that the benefits of these technologies can be fully realized, ultimately leading to more equitable health outcomes [7,18].

4.2. Integration of Telemedicine and AI in Diagnosis and Patient Monitoring

4.2.1. Advancing Remote Diagnostics Through AI and Telemedicine

The integration of AI and telemedicine has significantly enhanced the capacity for remote diagnostics and early disease prediction. Technologies such as AI-powered platforms for stroke diagnosis and diabetic retinopathy screening enable early identification of critical health issues, particularly in underserved regions where access to specialized care is limited [2,4,5]. For example, AI models have been shown to accurately detect retinal diseases using fundus photography and deep learning, which reduces the reliance on in-person examinations [15]. These advancements not only facilitate earlier interventions but also improve patient outcomes by providing timely and accurate diagnoses. As these tools evolve, their capacity to predict and monitor diseases remotely continues to bridge the gap in healthcare accessibility [2].

4.2.2. Wearable Technologies and IoT for Continuous Monitoring

The integration of wearable devices and Internet of Things (IoT) frameworks in telemedicine has revolutionized patient monitoring by enabling continuous data collection and real-time analysis [2]. Wearables such as smart socks for phlebopathic conditions and cardiac monitoring implants provide clinicians with actionable insights into patient health without requiring frequent in-person visits [5]. These technologies are particularly beneficial for managing chronic conditions, as they allow for early detection of complications and reduce the burden on healthcare systems. Moreover, the use of IoT facilitates seamless connectivity between devices and medical platforms, ensuring efficient data flow and enhancing the accuracy of remote monitoring systems [2].

4.2.3. Precision and Automation in Patient Monitoring Systems

Machine learning has become integral to telemedicine by improving the precision and reliability of patient monitoring systems [1]. Automated tools such as video-based activity recognition for Parkinson’s disease and neonatal sound quality assessment reduce the need for manual observations while delivering consistent results. These innovations also enable scalable monitoring solutions, particularly in clinical trials and large-scale health programs [5,13]. By leveraging advanced algorithms, telemedicine systems can provide precise diagnoses and insights, empowering healthcare providers to optimize care delivery [5,13]. This emphasis on automation not only enhances diagnostic accuracy but also alleviates the workload for healthcare professionals.

4.2.4. Scalability and Cost-Effectiveness of AI-Driven Solutions

The scalability and cost-effectiveness of AI-powered telemedicine solutions are pivotal in expanding healthcare access to diverse and resource-limited settings. Autonomous systems such as LumineticsCore for diabetic retinopathy have demonstrated their effectiveness in increasing screening rates while maintaining high diagnostic accuracy [16]. These systems are designed to operate seamlessly across varied practice environments, making them suitable for rural and urban healthcare facilities alike. Furthermore, the integration of AI with multimodal imaging, such as OCT angiography, supports complex diagnostic workflows and enhances the overall quality of care. As telemedicine technologies continue to advance, their affordability and adaptability will remain crucial for addressing global healthcare disparities [15].

4.3. Future Considerations of AI and Telemedicine in Rural Communities

AI and telemedicine are reshaping healthcare delivery, offering innovative solutions to address the persistent challenges faced by rural communities [3,10]. These technologies are advancing personalized care, improving diagnostics, facilitating remote monitoring, and reducing the time and cost associated with accessing healthcare services. As these tools continue to evolve, their potential for enhancing healthcare delivery in underserved areas becomes increasingly evident.

Key advancements include the development of a Real-Time AI and Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) Engine for Mobile Health Edge Computing. This technology uses Sparse Auto-Encoders Deep Learning and Group Method of Data Handling (GMDH) neural networks to predict diseases such as stroke, achieving high diagnostic accuracy and supporting remote medical care in smart living environments [2]. Similarly, AI-powered video-based activity recognition is being developed for automated motor assessments of conditions like Parkinson’s disease, enabling clinicians to remotely evaluate patient actions with precision [20].

The integration of IoT infrastructure in healthcare is also expanding, with innovative tools such as smart socks for detecting phlebopathic conditions and intelligent systems for low-cost remote disease detection and treatment [5]. For neonatal care, automated models that assess heart and lung sounds via telehealth applications are enhancing the quality of care by enabling accurate, remote estimations of heart and breathing rates, which are critical for preventing neonatal mortality and morbidity [11].

Machine learning models are also driving breakthroughs in predictive analytics, such as a frailty phenotype prediction model that achieved a sensitivity of 82.70% and specificity of 71.09%, underscoring the potential for AI to guide targeted interventions [22]. Additionally, programs like the Indian Health Service-Joslin Vision Network Teleophthalmology Program are leveraging AI and telemedicine to enhance compliance with diabetic retinopathy standards among underserved populations, including American Indians and Alaska Natives [3,16,17,19,25].

Emerging technologies continue to show promise for rural healthcare. For instance, robotic-assisted examinations, developed through initiatives like the ProteCT project during the COVID-19 pandemic, demonstrate how automation can address healthcare provider shortages [13,33]. Remote monitoring tools, such as the CardioMEMS device for hemodynamic status tracking, are enhancing chronic disease management by enabling real-time health monitoring and reducing hospitalizations [33].

Future applications of AI and telemedicine hold the potential to further transform rural healthcare [3,17,18]. Advances in imaging techniques, generative adversarial networks for enhancing portable ultrasound imaging, and tele-ophthalmology platforms are expanding diagnostic capabilities. These technologies, coupled with continuous innovation, will likely enable earlier interventions, more personalized care, and improved health outcomes for rural populations [10,18].

An integration of AI and telemedicine technologies offers a pathway to reducing healthcare disparities in rural communities. By enhancing diagnostic accuracy, enabling real-time monitoring, and facilitating access to care, these advancements are poised to revolutionize rural healthcare delivery, ultimately improving patient outcomes and healthcare efficiency. Continued investment in research, infrastructure, and equitable implementation will be critical to realizing the full potential of these transformative technologies.

4.4. Application of AI for Accurate and Early Diagnosis of Diseases Through Various Digital Tools

Some articles proposed the combined use of Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) mobile health app and AI to better serve patients residing in remote and hard to reach areas. More specifically, some studies combined IoT with AI for a more efficient data storage and management through a medical decision support system [8], for predicting some serious health issues [8], including the predictions of stroke, heart attack, brain strokes, and sudden fall [2], the telemonitoring and screening patients suffering from phlebopathic disease using smart sock technology [5], the evaluation of the sound quality of the hearts and lungs of newborn babies, using binary classification model, for future telehealth applications [11], the combination of telemedicine and AI to examine retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), and the use of teleophthalmology program for surveillance and management of diabetic retinopathy among American Indian and Alaska Native populations [23]. The main purpose of the program was to increase diabetic retinopathy screening rate [23]. While this article commented that teleophthalmology is more cost-effective than conventional dilated retinal examination to detect diabetic retinopathy, the authors mentioned that the use of AI systems for diabetic retinopathy diagnosis are not validated at the American Telemedicine Association Category 3 program, and the performance of these AI systems has not been studied among Amarian Indian and Alaska Native populations. The authors suggested that AI systems offer opportunities for the program to improve the performance of the Reading Center, as well as the triage of the patients [23]. Regardless, Boyle, Vignarajan, and Saha [26] embedded AI components (image quality and disease detection algorithm) into a telehealth platform to detect diabetic retinopathy among indigenous Australian communities residing in remote areas. Higher diabetic retinopathy detection rate was reported at the patient level than at the eye level [25].

Another study developed a third-party system to collect and administer remote monitoring RM (data) from implantable cardiac electronic devices (CIEDS) and enable a real-time and automatic centralized of CIEDS data from multiple hospitals [6]. While AI was not used in this study [6], the authors recommended that combining RM data resources with AI may further enhance the prediction of lead malfunctions, battery depletion, and arrhythmia [6].

The use of Human Activity Recognition, in terms of video recordings of body movements, and AI has also helped researchers predicting the severity of Parkinson’s disease based on the Movement Disorder Society Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) [4]. AI based on machine learning techniques with the combination of wireless wearable sensor devices (Internet of Things) was also used to determine patients’ physical frailty phenotypes (slowness, weakness, and exhaustion) [22]. AI, based on two-stage generative adversarial network, was used to obtain the optimal image quality of hand-held/portable ultrasound devices [26].

Some studies in our review used telemedicine without AI. Those studies are mostly concerned with COVID-19 (51 and 54). A telemedical diagnostic system equipped with a robotic arm was used to examine emergency patients, more specifically those who contracted infectious diseases such as COVID-19 [33]. The authors concluded that the acceptance of the new technology was high among physicians, and robotic telemedical devices have the potential to complement healthcare beyond COVID-19 [33]. Labetoulle at al.’s article [34] discussed the use of telescreening for remote ocular surface assessment as a solution to protect eye-doctors from contracting infectious disease, especially during COVID-19 pandemic. Ophthalmologists, among other eye doctors, have a higher risk of contracting COVID-19 because they need to closely approach the patients’ faces for effective eye exam and COVID-19 patients might need to see an ophthalmologist if SARS-CoV-2 causes conjunctival hyperemia [34]. However, the authors concluded that telescreening does not have the capability to replace standard ophthalmic examination, particularly for ocular surface disease. However, there is still hope of having effective telescreening thanks to groundbreaking research in high-technology imaging.

4.5. Insights into the Future Directions and Potential Innovations in AI and Telemedicine Specifically Geared Towards Enhancing Healthcare Delivery in Rural Communities

Future directions in the integration of artificial intelligence and telehealth highlight the potential to transform the healthcare landscape through innovative technologies. One promising example is the development of learning-based disease prediction models that utilize telemedicine and AI to screen for and diagnose eye and ear, nose, and throat (ENT) diseases [3]. These models have demonstrated the capability to remotely screen patients, monitor their conditions, prioritize healthcare resources, enhance disease prediction and diagnosis, and enable clinicians to provide more personalized treatment plans [3,24]. Additionally, deep learning models offer opportunities for greater patient involvement in their own healthcare, such as allowing individuals to capture medical images at home and securely share them with their clinicians for further analysis [10].

However, the integration of AI and telehealth must also address critical ethical and regulatory considerations to ensure these technologies are implemented effectively and responsibly. Key policy recommendations include providing comprehensive training for nurses, clinicians, and other healthcare professionals to enhance their technological literacy and ensure they can confidently utilize these tools [3]. Equally important is educating patients on how to properly use at-home healthcare technologies to promote engagement and accuracy in remote care. Furthermore, it is essential to address challenges related to patient privacy and informed consent by establishing clear guidelines that safeguard sensitive health data and ensure transparency in AI-driven decision-making. Another critical consideration is the careful design and rigorous testing of AI algorithms to minimize biases that could lead to disparities in healthcare delivery and outcomes. Ensuring fairness, accountability, and equity in AI applications will be crucial for maximizing their benefits while maintaining trust and ethical standards in healthcare.

Including underrepresented communities is important to ensure an equity of outcome for those patient population that are being served [10]. Another policy recommendation is to standardize how data collected from IoT’s are formatted, how data are collected, who owns the data, and how that data are used and protected [14,29]. Standardization of data ensures that the data that is collected is reliable and consistent across different healthcare systems and allows IOT devices to share information. Those in healthcare also have an ethical duty to ensure that patients’ personal data are safe and secure; therefore, a risk management policy should be created to ensure that a patient’s data are safe [17].

Future telemedicine platforms have the potential to incorporate AI and IoT devices to enhance patient care, increase accessibility, and decrease costs. Potential innovations include AI-driven diagnostic tools [24]. An AI-driven diagnostic tool is a software application that uses AI algorithms to assist in the diagnosis of medical conditions. Many AI-driven algorithms that are currently being developed for rural communities involve the analysis of medical images to detect and diagnosis patients with diseases. IoT devices can also be utilized to collect large amounts of continuous data for AI algorithms to analyze and make clinical diagnoses [24]. The idea of these AI-driven diagnostic tools is to enable nonclinical specialists to be able to diagnose patients with diseases in rural areas where there are not a lot of clinical specialists. Doing so would decrease the health inequality gaps that rural patients face by increasing access to healthcare. However, employers must provide training programs to educate non-clinical healthcare workers on how to use these AI-driven diagnostic tools efficiently and accurately [16,17]. AI-driven diagnostic tools can be pushed even further. When enough advancements in AI-driven diagnostic tools have been made, these tools can be used by patients themselves to diagnosis themselves [10]. If this is to be achieved, then patients too must be trained in how to diagnosis themselves. However, these tools must be patient, friendly and easy to use. Future directions should also include the creation and implementation of security measures for the data that is collected from patients, transferred, and stored for patients [29]. IoT devices capture large amounts of private medical information that are protected by HIPPA. To avoid legal issues, strict security and privacy standards as well as a top-notch security system should be put in place for the safe storage of information and safe communication among IoT devices and the place where the data will be stored [24]. If such standards are not put in place, third parties could obtain access to that data and perform unauthorized activities with that data [24].

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary of Findings

With the increased access to care in hard-to-reach rural communities, thanks to telemedicine, and the improved accuracy in diagnostic thanks to the use of AI, the authors review extant peer-reviewed articles published between January 1, 2020, and December 31, 2024 to synthesize the findings regarding the impact of the AI and telemedicine on patient diagnoses and quality of care in rural areas. Three constructs emerged from the review of the 40 articles that met the inclusion criteria, namely the challenges and benefits of the use of AI and telemedicine in rural communities, the integration of telemedicine and AI in diagnosis and patient monitoring, and the future considerations of AI and telemedicine in rural communities.

5.2. Review Contributions

Some of the barriers to the widespread adoption of AI and telemedicine in rural areas consist of the lack of resources and infrastructure that these technologies require, high cost, and shortage of specialized workforce, including healthcare providers, who are expected to use these technologies. Other barriers to adoption consist of concerns regarding data privacy and protection as well as whether technology is easy to use. Regardless, telemedicine and AI provide some healthcare benefits. For instance, telemedicine has been found to expand timely communication with healthcare providers and patients residing in remote areas; telemedicine eliminates travel costs and lengthy travel times. Also, the use of AI to assist healthcare providers with accurate diagnosis can increase quality of care because with accurate diagnosis, patients receive the appropriate treatment for their diseases, increasing the probability of positive health outcomes.

Regarding the use of AI and telemedicine to enhance diagnostic accuracy and continuity in patient monitoring, this review found that AI and telemedicine have been used to predict stroke, heart attacks, physical frailty and sudden fall, monitor implantable cardio-electronic devices, and monitor phlebopathic patients, as well as those diagnosed with type II diabetes, especially to prevent blindness due to diabetic retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration. These technologies have also been used to detect and diagnose cancer.

Based on our review, both telemedicine and AI have the potential to improve access to patient diagnosis and therefore quality of care in rural healthcare organizations. There is an emerging trend combining telemedicine and AI to further improve access to and quality of care, with respect to accurate disease prediction and diagnosis, as well as health outcomes. However, nationwide regulations, protocols, and guidelines are needed to standardize telehealth and telemedicine services, ensure ethical practices, mitigate bias that may be embedded in healthcare data when used in AI.

5.3. Review Limitations

While studying the impact of AI on patient diagnoses and quality of care has profound implications for access to care and access to technology, it is essential to recognize and address the limitations inherent in studies such as sample bias, measurement bias, and ethical concerns during the investigation of this complex research topic. Additionally, a formal quality assessment of each article identified in the review could provide deeper insights and enhance the robustness of the findings, in an attempt to future reduce bias and/or assess rigor in future research.

5.4. Future Directions and Possible Applications

Future directions discussed include the development of technology that could change the healthcare landscape with the incorporation of AI technology and telehealth. One such example is the creation of a learning-based disease prediction model that uses telemedicine and AI to screen for and diagnosis eye and ENT diseases [3]. This model has revealed the potential to remotely screen patients, track patient conditions, prioritize resources, improve disease predictions, diagnosis, and classification, and allow clinicians to provide personalized treatment to patients [3,24]. Other deep learning models have the potential to allow patients to become more involved in their healthcare, such as by allowing patients to take images at home and send them to their clinicians [10].

The research team identified the integration of the Internet of Things (IoT) and AI with telemedicine as a relevant concept that may hold future potential for enhancing healthcare delivery. IoT-enabled devices can provide real-time patient data, while AI algorithms can analyze this information to support timely and accurate clinical decision-making in remote settings, supporting the premise of this review. This convergence presents a promising opportunity for future research to explore its impact on improving diagnostic precision, patient monitoring, and overall healthcare accessibility, particularly in underserved communities.

When discussing the future direction of incorporating AI with telehealth, one must also consider policy recommendations to ensure that these innovative technologies are used ethically and to their fullest potential. Policy recommendations that should be considered include having nurses, clinicians, and other healthcare providers be trained in technological literacy [3]. On top of this, patients should also be trained in how to use these at home technologies. Another policy recommendation is to ensure that algorithms are carefully designed and tested to mitigate any amount of bias. Including underrepresented communities is important to ensure an equity of outcome for those patient population that are being served [10]. Another policy recommendation is to standardize how data collected from IOT’s are formatted, how data are collected, who owns the data, and how that data are used and protected [14,29]. Standardization of data ensures that the data that is collected is reliable and consistent across different healthcare systems and allows IOT devices to share information. Those in healthcare also have an ethical duty to ensure that patients’ personal data are safe and secure; therefore, a risk management policy should be created to ensure that a patient’s data are safe [17]. In conclusion, further research into the infrastructure, political landscape, and socioeconomic factors that influence the adoption of artificial intelligence and telemedicine in diverse rural settings is essential to fully understand and address the challenges and opportunities these technologies present.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to this review in accordance with ICMJE standards. K.P., D.W. and C.L. primarily led the research, team initiatives, and guidance throughout the research process. K.P., D.W., A.A., K.L., C.L. and Z.R. contributed to the investigation into the research topic, participation in the method of the review, and original drafting of the manuscript. Discussion and analyses of review results were conducted by all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nashwan, A.J.; Gharib, S.; Alhadidi, M.; El-Ashry, A.M.; Alamgir, A.; Al-Hassan, M.; Khedr, M.A.; Dawood, S.; Abufarsakh, B. Harnessing Artificial Intelligence: Strategies for Mental Health Nurses in Optimizing Psychiatric Patient Care. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 44, 1020–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbagoury, B.M.; Zaghow, M.; Salem, A.-B.M.; Schrader, T. Mobile AI Stroke Health App: A Novel Mobile Intelligent Edge Computing Engine based on Deep Learning models for Stroke Prediction—Research and Industry Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 20th International Conference on Cognitive Informatics & Cognitive Computing (ICCI*CC), Banff, AB, Canada, 29–31 October 2021; pp. 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyaya, P.; Upadhyay, S.K.; Shrestha, A.; Shrestha, N.; Shrestha, R.; Khatri, B.; Pandey, J.; Subedi, A.; Dhungana, S. Use of telemedicine and artificial intelligence in Eye and ENT: A boon for developing countries. In Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Speech Technology (AIST), Delhi, India, 9–10 December 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarapata, G.; Dushin, Y.; Morinan, G.; Ong, J.; Budhdeo, S.; Kainz, B.; O’Keeffe, J. Video-Based Activity Recognition for Automated Motor Assessment of Parkinson’s Disease. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Informatics 2023, 27, 5032–5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelantonio, E.; Lucangeli, L.; Camomilla, V.; Pallotti, A. Smart sock-based machine learning models development for patient screening. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Industry 4.0 & IoT (MetroInd4.0&IoT), Trento, Italy, 7–9 June 2022; pp. 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasumi, E.; Fujiu, K.; Nakamura, K.; Yumino, D.; Nishii, N.; Imai, Y.; Shoda, M.; Komuro, I. A mutually communicable external system resource in remote monitoring for cardiovascular implantable electronic devices. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2023, 47, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preity; Ranjan, R.; Verma, K.; Sahana, B.C. A Computer-Aided Prediagnosis System for Health Prediction Based on Personal Health Data. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 12th International Conference on Communication Systems and Network Technologies (CSNT), Bhopal, India, 8–9 April 2023; pp. 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, K.; Bajwa, I.S.; Ramzan, S.; Anwar, W.; Khan, A. An Intelligent IoT Based Healthcare System Using Fuzzy Neural Networks. Sci. Program. 2020, 2020, 8836927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, S.E.; Agurto, C.; Cecchi, G.A.; Eyigoz, E.; Hershey, B.; Lechleiter, K.; Huynh, D.; McDonald, M.; Rogers, J.L. The Impact of COVID-19 on Chronic Pain: Multidimensional Clustering Reveals Deep Insights into Spinal Cord Stimulation Patients. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Digital Health (ICDH), Chicago, IL, USA, 2–8 July 2023; pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiburg, K.V.; Turner, A.; He, M. Telemedicine and delivery of ophthalmic care in rural and remote communities: Drawing from Australian experience. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2022, 50, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grooby, E.; He, J.; Kiewsky, J.; Fattahi, D.; Zhou, L.; King, A.; Ramanathan, A.; Malhotra, A.; Dumont, G.A.; Marzbanrad, F. Neonatal Heart and Lung Sound Quality Assessment for Robust Heart and Breathing Rate Estimation for Telehealth Applications. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Informatics 2021, 25, 4255–4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Jia, X.; Li, G.; Guo, D.; Xi, X.; Zhou, T.; Liu, J.-B.; Zhang, B. Development of 5G-based Remote Ultrasound Education: Current Status and Future Trends. Adv. Ultrasound Diagn. Ther. 2023, 7, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Zhou, C.; Bai, J.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, B.; Wang, J.; Fu, L.; Long, H.; Huang, X.; Zhao, J.; et al. Current advancements in therapeutic approaches in orthopedic surgery: A review of recent trends. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1328997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Adhikary, A.; Laghari, A.A.; Mitra, S. Eldo-care: EEG with Kinect sensor based telehealthcare for the disabled and the elderly. Neurosci. Informatics 2023, 3, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almadhi, N.H.; Dow, E.R.; Chan, R.V.P.; Alsulaiman, S.M. Multimodal Imaging, Tele-Education, and Telemedicine in Retinopathy of Prematurity. Middle East Afr. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 29, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.; Weitzman, D.; Lemerond, M.; Jones, A. Determinants for scalable adoption of autonomous AI in the detection of diabetic eye disease in diverse practice types: Key best practices learned through collection of real-world data. Front. Digit. Health 2023, 5, 1004130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Yusufu, M.; Liu, Y.; Mou, D.; Chen, X.; Tian, J.; Li, H.; et al. Economic evaluation of combined population-based screening for multiple blindness-causing eye diseases in China: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e456–e465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Choudhury, R.; Kotwal, A. Achieving health equity through healthcare technology: Perspective from India. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2023, 12, 1814–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, C.J.; Garg, S. Telemedicine for Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Telemed. e-Health 2020, 26, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, S.; Côté, D.; Grimes, D.; Mestre, T. A digital companion (eCARE-PD platform) for people living with Parkinson: A co-design study. Int. J. Integr. Care 2022, 22, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadlamani, L.N.; Sharma, V.; Emani, A.; Gowda, M.R. Telepsychiatry and Outpatient Department Services. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 42, 27S–33S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Mishra, R.; Sharafkhaneh, A.; Bryant, M.S.; Nguyen, C.; Torres, I.; Naik, A.D.; Najafi, B. Digital Biomarker Representing Frailty Phenotypes: The Use of Machine Learning and Sensor-Based Sit-to-Stand Test. Sensors 2021, 21, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonda, S.J.; Bursell, S.-E.; Lewis, D.G.; Clary, D.; Shahon, D.; Horton, M.B. The Indian Health Service Primary Care-Based Teleophthalmology Program for Diabetic Eye Disease Surveillance and Management. Telemed. e-Health 2020, 26, 1466–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raoof, S.S.; Durai, M.A.S. A Comprehensive Review on Smart Health Care: Applications, Paradigms, and Challenges with Case Studies. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2022, 2022, 4822235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, J.; Vignarajan, J.; Saha, S. Automated Diabetic Retinopathy Diagnosis for Improved Clinical Decision Support. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2024, 310, 1490–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Qi, Y.; Yu, J. Image Quality Improvement of Hand-Held Ultrasound Devices With a Two-Stage Generative Adversarial Network. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 67, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montilla, I.H.; Mac Carthy, T.; Aguilar, A.; Medela, A. Dermatology Image Quality Assessment (DIQA): Artificial intelligence to ensure the clinical utility of images for remote consultations and clinical trials. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 88, 927–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensah, G.A.; Fuster, V.; Murray, C.J.; Roth, G.A.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbasian, M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdollahi, A.; Abdollahi, M.; Abdulah, D.M.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks, 1990–2022. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 2350–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Eijck, S.; Janssen, D.; van der Steen, M.; Delvaux, E.; Hendriks, H.; Janssen, R. Digital health applications to establish a remote diagnosis for orthopedic knee disorders: A scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 25, e40504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz-Garcia, A.; Fabelo, H.; Rodriguez-Almeida, A.J.; Zamora-Zamorano, G.; Castro-Fernandez, M.; Ruano, M.d.P.A.; Solvoll, T.; Granja, C.; Schopf, T.R.; Callico, G.M.; et al. Quality, Usability, and Effectiveness of mHealth Apps and the Role of Artificial Intelligence: Current Scenario and Challenges. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e44030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jim, H.S.L.; Hoogland, A.I.; Brownstein, N.C.; Barata, A.; Dicker, A.P.; Knoop, H.; Gonzalez, B.D.; Perkins, R.; Rollison, D.; Gilbert, S.M.; et al. Innovations in research and clinical care using patient-generated health data. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 182–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, A.; Macy, E.; Chiriac, A.-M.; Blumenthal, K.G. Drug Allergy Labels Lost in Translation: From Patient to Charts and Backwards. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 3015–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berlet, M.; Fuchtmann, J.; Krumpholz, R.; Naceri, A.; Macari, D.; Jähne-Schon, C.; Haddadin, S.; Friess, H.; Feussner, H.; Wilhelm, D. Toward telemedical diagnostics—Clinical evaluation of a robotic examination system for emergency patients. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076231225084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labetoulle, M.; Sahyoun, M.; Rousseau, A.; Baudouin, C. Ocular surface assessment in times of sanitary crisis: What lessons and solutions for the present and the future? Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 31, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afari, M.E.; Syed, W.; Tsao, L. Implantable devices for heart failure monitoring and therapy. Heart. Fail. Rev. 2018, 23, 935–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyo, J.; Marini, T.J.; Saavedra, A.C.; Toscano, M.; Baran, T.M.; Drennan, K.; Dozier, A.; Zhao, Y.T.; Egoavil, M.; Tamayo, L.; et al. No sonographer, no radiologist: New system for automatic prenatal detection of fetal biometry, fetal presentation, and placental location. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).