Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Self-regulation-based interventions effectively enhance self-care behaviors, knowledge, and self-efficacy among patients with type 2 diabetes.

- The integrative model proposed in this systematic review explains the relationship between disease interpretation, coping strategies, and family involvement in diabetes self-management.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The new integrative model can guide healthcare professionals in designing more comprehensive and patient-centered diabetes education programs.

- Strengthening self-regulation and family support is essential to improve glycemic control and quality of life among patients with type 2 diabetes.

Abstract

Background/Objectives: Self-care is essential in managing type 2 diabetes (T2DM), yet it remains suboptimal among patients. This systematic review aimed to determine whether self-regulation-based self-management interventions improve glycemic control, self-efficacy, and quality of life among adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), including individual and family-based approaches. Methods: Four major databases (Scopus, ScienceDirect, ProQuest, and PubMed) were systematically searched for English-language studies following PRISMA guidelines. Screening was performed using Rayyan, and study quality was assessed with the JBI critical appraisal tool. Data were synthesized based on PICO outcomes and study design to identify key patterns. The review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024594398). Results: A total of 881 articles were identified, and 31 met the inclusion criteria. Most studies were randomized controlled trials (54.8%), with diabetes self-management education (DSME) being the most common intervention (41.9%), followed by self-regulation training (12.9%). Nearly half of the studies measured blood glucose and quality-of-life outcomes (22.6%), while others focused on knowledge, behavior, and self-efficacy (19.4%). Only a few studies addressed individual and family-oriented interventions. Conclusions: DSME and self-regulation-based approaches are recommended as complementary strategies to improve diabetes self-management. This review introduces a novel integrative model linking disease interpretation, coping strategies, and family support, and highlights their influence on patient self-care behaviors. Future research should empirically test this model to clarify the dynamic interactions among its domains and their effects on glycemic control and health outcomes.

1. Introduction

Self-care is a deliberate practice of actions to improve and maintain physical, mental, and emotional health, helping individuals live well, manage stress, and prevent illness [1]. In type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), self-care is essential for maintaining healthy blood glucose levels and preventing complications [2]. However, inadequate self-care capacity often results in poor outcomes, frequently associated with non-adherence to medication, diet, and lifestyle recommendations [3,4]. A major factor underlying these limitations is ineffective self-regulation, which significantly influences quality of life among individuals with T2DM [5].

Self-regulation plays a central role in motivating individuals to engage in sustainable behavioral changes [6]. The Individual and Family Self-Management Theory (IFSMT) provides a practical framework that emphasizes the combined roles of patients and their families in managing diet, exercise, blood glucose monitoring, and medication adherence [7,8]. Integrating family support strengthens patients’ ability to maintain effective disease management and improves quality of life [9,10]. In this review, self-regulation is defined as the capacity of people with T2DM to consciously monitor, control, and adjust their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors to engage in self-care practices consistently, encompassing cognitive, affective, and behavioral processes essential for treatment adherence [10].

To frame the self-regulation conceptually, we draw on Leventhal’s Self-Regulation Model and Baumeister’s Self-Regulation Theory, which explain how illness perceptions and self-control mechanisms influence self-care behaviors [11,12]. Unlike cognitive–behavioral therapy and other professionally driven interventions, which often rely on repeated facilitation, self-regulation approaches emphasize patient autonomy, enabling individuals to set goals, monitor progress, and self-correct over time, making them particularly suitable for chronic diseases such as T2DM [9,13,14].

Previous research has shown that self-regulation among people living with type 2 diabetes is still relatively low, with only about 46.5% demonstrating adequate levels [15]. According to the Common-Sense Model of Illness, self-regulation is shaped by individuals’ cognitive representations of their condition, including beliefs about symptoms, consequences, controllability, and treatment effectiveness. Therefore, the low self-regulation levels observed in this population may reflect maladaptive or inaccurate illness representations, which need to be addressed when designing interventions [16]. Similarly, a study in China reported that adherence to self-care management, including diet, physical activity, health monitoring, and foot care, was mostly in the moderate (50.4%) and low (33.6%) categories [17].

Globally, T2DM accounts for over 90% of all diabetes cases, with 536.6 million individuals affected in 2021 and an estimated 783.2 million by 2045 [18,19]. Prevalence is higher in lower socioeconomic groups and increases with age, particularly affecting those aged 45 and older [20]. These trends underscore the importance of effective self-management interventions that integrate self-regulation principles.

Self-regulation-based interventions grounded in IFSMT have demonstrated improvements in blood glucose levels and quality of life, largely due to the incorporation of family support into daily self-care routines [10]. Emotional regulation therapies, including Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), complement these approaches by enhancing mindfulness, acceptance, emotional awareness, and adaptive coping, directly supporting patients in stress management, motivation, and adherence to self-care behaviors [21,22,23]. Techniques such as goal-setting, self-monitoring, and problem-solving further operationalize self-regulation in practical diabetes management [9,24].

Integrating IFSMT-based strategies with emotional regulation approaches provides a holistic method for diabetes self-management, linking theoretical models of self-regulation with practical interventions. By fostering patients’ autonomy and engagement, these approaches translate cognitive and emotional regulation into consistent self-care behaviors, ultimately strengthening long-term disease management.

In light of these findings, this systematic review seeks to provide empirical insights into self-regulation interventions grounded in individual- and family-centered self-management theories as a promising strategy to enhance self-care and quality of life among individuals with T2DM. Furthermore, it proposes a comprehensive conceptual model offering an in-depth perspective on self-regulation mechanisms in T2DM management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [25] and was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024594398). The inclusion and exclusion criteria were determined using the PICOS framework as follows:

- Inclusion Criteria:

- Population (P): Adults diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

- Intervention (I): Interventions explicitly designed to enhance self-regulation in the management of type 2 diabetes. These included behavioral, psychosocial, or educational programs that integrated core self-regulation components such as goal-setting, self-monitoring, problem-solving, coping strategies, and appraisal of outcomes [9,26]. Educational programs that provided only didactic information or knowledge transfer, without these self-regulation components, were excluded.

- Comparison (C): Control groups receiving either standard care or non-self-regulation-based interventions.

- Outcomes (O): Quantitative assessment of diabetes self-care behaviors (e.g., knowledge, diet, physical activity, medication adherence, blood glucose levels monitoring, stress management, and foot care), and quality of life measured via validated questionnaires (covering physical, psychological, social, and environmental domains, including FBG and HbA1c levels).

- Study Design (S): Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) and quasi-experimental studies.

- Language and Timeframe: Articles published in English between 2014 and 2023.

- Exclusion Criteria:

- Non-primary research such as reviews, editorials, conference abstracts, and study protocols,

- Case reports or applied development studies,

- Qualitative studies or studies with purely descriptive designs.

2.2. Search Strategy

The literature search for this review was conducted between May and July 2024, and eligible studies were restricted to those published between 2014 and 2023. The search covered four primary electronic databases: Scopus, Science Direct, PubMed, and ProQuest, as recommended for systematic reviews to ensure comprehensiveness. A search of all databases was conducted using the following keywords and Boolean operators: (‘self-regulation’ OR ‘self-regulation model’) AND (individual and family self-management theory’ OR ‘IFSMT’ OR ‘family’) AND (‘self-management’ OR ‘self-care’ OR ‘DSME’) AND (‘type 2 diabetes’ OR ‘DMT2’ OR ‘DM2’). All keywords were matched to Medical Subject Headings (MeSH). The complete search strategy for all resources is available in Refs. [9,10,14,24,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51].

2.3. Study Selection

All authors participated in the selection process by screening studies retrieved from academic databases. A total of 881 articles were identified from four major databases and imported into Rayyan (https://rayyan.ai, accessed on 1 May 2024), an intelligent web-based platform specifically designed for systematic reviews. Rayyan was chosen due to its advantages in enabling blinded, independent screening by multiple reviewers, automatic duplicate detection, and efficient tagging of inclusion/exclusion decisions, thereby improving accuracy and reducing selection bias.

After automatic duplicate removal, 364 studies remained for title and abstract screening. Four authors independently reviewed these using predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria based on the PICOS framework. Studies were included if the intervention explicitly incorporated self-regulation elements into diabetes self-management education, rather than education-only programs.

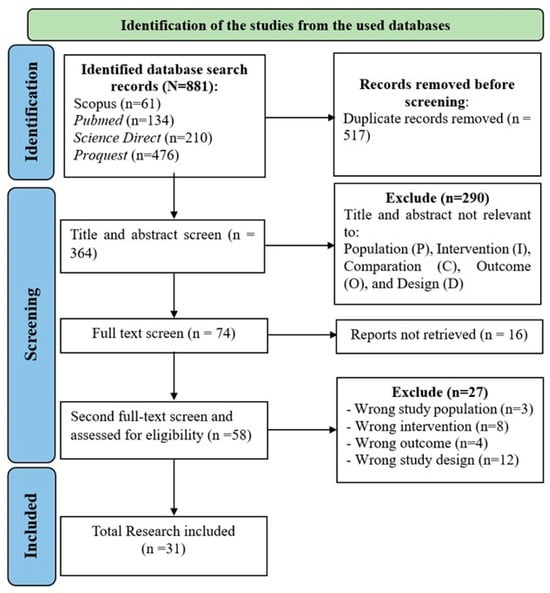

A total of 74 articles underwent full-text review. Of these, 58 studies met the eligibility criteria and were further analyzed. Any disagreements among the review team were resolved through discussion and, if necessary, adjudicated by a third, independent reviewer. A consensus level of 80% or higher was considered to indicate strong inter-reviewer agreement [52,53]. Finally, 31 studies were included in the review, as illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study Selection (adapted from the PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram) [25].

2.4. Data Extraction, Analysis, and Synthesis

Data from each eligible study were extracted into a standardized Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. To ensure accuracy, data extraction was independently performed by two reviewers. Extracted items included study characteristics, participant demographics, intervention content, duration, and reported outcomes. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus, with adjudication by a third reviewer when required.

Due to substantial heterogeneity in the types and durations of self-regulation or self-management interventions, study designs, and reported outcomes, meta-analysis was not feasible. Instead, a narrative and thematic synthesis approach was adopted. Following the PICO framework, the extracted data were first organized into the following categories: Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, and Study Design. Next, an inductive thematic synthesis was conducted following (1) line-by-line coding of relevant findings, (2) grouping codes into descriptive categories, and (3) generating higher-order analytical themes. Coding was performed independently by two reviewers and then cross-checked for consistency. Final themes were refined and agreed upon through iterative team discussions. This process ensured transparency and minimized bias in synthesizing the evidence base [54].

2.5. Risk of Bias and Study Quality

The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated using the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool, applied according to study design. This assessment examined potential sources of bias related to study design, implementation, and analysis. Each study type had its own set of appraisal questions, which were reviewed individually.

The JBI tool covers key methodological aspects, including clarity of research objectives (Q1), appropriateness of the study design (Q2), adequacy of sampling and participant selection (Q3), rigor of data collection procedures (Q4–Q6), strategies for handling confounding factors (Q7–Q8), validity and reliability of outcome measurements (Q9–Q11), and appropriateness of statistical analysis (Q12–Q13).

Quality scores were converted into percentages and categorized as ≥75% = Good, 50–74% = Enough, and <50% = Poor [55]. Only studies meeting acceptable methodological quality were included in the final synthesis.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

This systematic review identified 881 studies across all specified databases, of which only 31 met the inclusion criteria. Table 1 describes the percentage of study characteristics that were obtained.

Table 1.

Description of Study Characteristics (n = 31).

Based on Table 1, most of the included studies were RCTs (17; 54.8%). The interventions applied to type 2 diabetes patients varied considerably, but in this review, they were grouped into two major categories based on their theoretical foundations. Diabetes Self-Management Education (DSME) interventions (13; 41.9%) primarily emphasized structured education to improve diabetes knowledge, dietary adherence, physical activity, medication use, and blood glucose monitoring. Although several DSME programs incorporated elements of self-regulation, such as goal-setting and self-monitoring, their central framework was educational rather than regulatory. By contrast, self-regulation training programs (4; 12.9%) explicitly adopted self-regulation theory as their conceptual basis, focusing on mechanisms such as problem interpretation, goal-setting, emotion regulation, feedback, and appraisal of coping success. Some of these programs also involved family members in order to strengthen patients’ regulatory capacity through social and emotional support. These family-oriented approaches were classified as self-regulation training because their primary focus was on enhancing regulatory processes within both individual and family contexts.

Although DSME was the most frequently used intervention, only a small number of studies explicitly used self-regulation as the theoretical model. This overlap illustrates a broader challenge in the literature, where DSME and self-regulation interventions often share components, making clear distinctions difficult. This also highlights an important methodological implication: while DSME emphasizes structured education, incorporating regulatory elements blurs the boundaries between educational and psychological approaches. Furthermore, behavior change interventions often require long-term follow-up and comprehensive psychological assessments, which may not be feasible in all settings [28]. Consequently, the interpretation of findings across studies must take into account the heterogeneity of intervention design and outcome measures, an issue that will be further addressed in Section 4.

3.2. Risk of Bias and Study Quality

Of the 31 included studies, 28 (90.3%) were rated “Good” quality, with a JBI critical appraisal score above 75.0%. These studies demonstrated clear methodological rigor, including well-described interventions, valid outcome measurements, and appropriate statistical analysis. However, three studies (9.7%) received a “Moderate” rating due to methodological limitations, such as unclear randomization procedures, small sample sizes, and lack of blinding. Despite these limitations, the studies were included due to their relevance, and their findings were interpreted with caution in the synthesis. The full assessment is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Checklist for Randomized Control Trial and Non-Randomized Control Trial from the JBI.

3.3. Impact of Intervention on Type 2 Diabetes Patients

A review of 18 studies found that diabetes self-management interventions improved knowledge, self-management behaviors, self-efficacy, emotional responses, quality of life, and glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, six studies applied information system-based self-management interventions to improve behavior and quality of life. In another intervention, four studies applied self-regulation training programs to improve knowledge, self-management behaviors, self-efficacy, emotional responses, quality of life, and glycemic control in patients with DM type 2. Meanwhile, three studies included individual and family interventions to improve self-management. This showed the need to develop an intervention that includes one family member in self-management to improve health status.

3.3.1. Thematic Synthesis

An inductive thematic synthesis was conducted to integrate findings from the included studies. The analysis involved line-by-line coding, grouping codes into descriptive categories, and generating higher-order analytical themes. To enhance transparency and reproducibility, we provide a thematic development matrix summarizing the progression from initial codes to categories and final themes (Table 3). This table forms the foundation for interpreting the intervention impacts described in the subsequent sections.

Table 3.

Thematic Synthesis.

The thematic synthesis generated seven interrelated themes that represent the core mechanisms by which self-management and self-regulation interventions influence outcomes among individuals with type 2 diabetes. Collectively, these themes highlight that cognitive preparation through education, behavior modification strategies, and strengthened self-efficacy form the foundational components of effective self-regulation. Family engagement and multi-modal health system support further enhance intervention uptake and continuity. Notably, metabolic improvements were consistently associated with interventions incorporating goal-setting, self-monitoring, appraisal processes, and emotional coping. Together, these themes underpin the development of the integrative model by illustrating the multilevel interactions between individual, family, and healthcare system factors that shape diabetes self-management (Table 3).

3.3.2. Impact of Diabetes Self-Management Intervention

Nearly all studies in this systematic review evaluated the effectiveness of DSME interventions on knowledge, self-management behaviors, self-efficacy, emotional responses, quality of life, and glycemic control in people with type 2 diabetes. Interventions delivered through 2 h of weekly face-to-face sessions over 3 months demonstrated improvements in self-management behaviors, self-efficacy, and reductions in HbA1c [24,31,32,33,46,50]. Some studies also reported sustained benefits for up to 6 months [27,34,35,41,42,56], while DSME programs implemented for 9–12 months showed continued improvements in quality of life [43,44,47].

However, the use of varying intervention durations and educational structures makes direct comparison across studies challenging. While this variation reflects the flexibility of DSME programs to adapt to different clinical and community settings, it also limits the ability to draw standardized conclusions regarding the optimal “dose” of DSME. The heterogeneity of intervention length and content suggests the need for more consistent reporting and standardized frameworks in future studies to strengthen comparability and synthesis of outcomes. Additionally, several studies have shown that patients who regularly receive DSME tend to experience fewer complications, better glycemic control, and improved quality of life, particularly when structured tools such as the Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ) are used [57].

This study demonstrates that different questionnaires are used across studies that assess the outcomes of the DSME intervention. Specifically, questions were developed based on the Diabetes Knowledge Scale (DKS) [58]. To determine indicators of self-care management activity through the Diabetes Self-Care Activities Scale (SDSCA) questionnaire [59]. Meanwhile, patients’ emotional responses were measured using the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) [60] and the Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) [61]. The results show a significant impact on quality of life, as measured by the WHOQOL-BREF [62] and the Diabetes Quality of Life (DQOL) [63]. Therefore, this systematic review demonstrates that DSME intervention outcomes can be measured using several questionnaire modifications.

3.3.3. Impact of the Self-Regulation Training Program Intervention

Based on this systematic review, four studies implemented self-regulation interventions to improve diabetes knowledge, self-management behaviors, self-efficacy, emotional responses, quality of life, and glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes [9,10,14,24]. These interventions typically consisted of multiple components, such as educational sessions and behavioral skill-building activities delivered over 3 weeks, and were shown to effectively improve self-management behaviors and reduce HbA1c levels [9,10,14].

There were no statistically significant changes in HbA1c at 12-month follow-up in one study, although clinical improvements were observed. This may be attributable to factors such as environmental influences, small sample size, or the long duration between intervention and evaluation [29]. Other studies showed that family-oriented self-management programs produced favorable effects on HbA1c [26], emphasizing the important role of family in supporting diabetes management. A study from China also reported that such interventions were effective in community health centers for reducing HbA1c after approximately 3 months [36], as summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of Study Descriptions (n = 31).

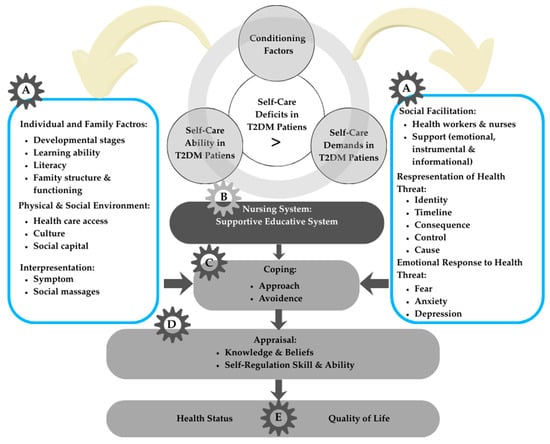

3.4. Development of a New Integrative Model

Although this review demonstrated that both Diabetes Self-Management Education (DSME) and self-regulation training interventions positively influenced knowledge, self-care behaviors, self-efficacy, quality of life, and glycemic control, it also revealed substantial overlap between the two approaches. Many DSME programs included self-regulation components such as goal-setting and self-monitoring, while self-regulation training interventions sometimes incorporated educational aspects. This overlap highlighted the difficulty of drawing a clear distinction between DSME and self-regulation programs and pointed to the need for an integrative framework that captures their shared mechanisms while accounting for contextual influences from individual, family, and environmental factors. To address this gap, a new integrative model was developed that synthesizes elements of self-regulation theory, the IFSMT, and self-care frameworks, as presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Integrative model of self-regulation in T2DM self-management. Letters denote model components: A—Conditioning factors; B—Interaction between self-care ability and demands; C—Coping strategies (approach or avoidance); D—Appraisal process (knowledge, beliefs, and self-regulation skills); E—Outcomes (health status, quality of life, and cost of health).

The factors discussed below describe a new integrative model that explains the relationships among the self-regulation model, individual and family self-management theory (IFSMT), and self-care interventions in patients with type 2 diabetes. The development of this new integrative model is structured into five domains, derived from the systematic review and the synthesis of multiple theoretical frameworks, as illustrated in Figure 2.

The integrative model was developed by systematically mapping the seven analytical themes derived from the thematic synthesis (Table 3) onto each model component (Figure 2). This explicit linkage ensures that the framework is empirically grounded, theoretically coherent, and transparently derived from the included studies.

3.4.1. Factors That Influence Individuals and Families with Type 2 Diabetes (Part A)

Changes in self-management behavior are essential for improving the quality of life and preventing complications in individuals with T2DM. According to the IFSMT framework, behavior change requires a contextual foundation comprising risk factors and supportive conditions. In the integrative model, Part A represents conditioning factors that influence a person’s ability to engage in effective self-care. Personal characteristics such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, family history of diabetes, disease severity, and duration shape coping tendencies, as demonstrated in previous studies showing that older age and longer disease duration are associated with lower adherence to self-care [20].

Disease interpretation also arises within this component, involving symptom recognition, understanding treatment needs, and beliefs about disease causes, which have been linked to self-management outcomes [20]. Environmental factors, including physical and social surroundings, influence perceptions and self-management capabilities, with studies highlighting the role of community support and access to resources in facilitating effective diabetes care [64]. Family-related factors, such as knowledge, caregiving skills, family functioning, and health literacy, are key contextual influences determining how individuals and families respond to diabetes challenges, as reported in [57].

3.4.2. Nursing System (Intervention)

In the integrative model (Part B), the nursing system serves as the mechanism through which healthcare professionals provide supportive educational interventions when individuals’ self-care abilities are insufficient to meet their self-care demands [58]. Within the included studies, this system was most commonly operationalized through Diabetes Self-Management Education (DSME), structured self-care programs, and self-regulation–oriented interventions delivered by nurses or multidisciplinary teams [9,14]. While these interventions collectively aim to strengthen self-care ability, their modes of delivery vary, reflecting different emphases on education, behavioral skill-building, emotional regulation, and coping guidance.

Rather than functioning as isolated components, these interventions interacted with the conditioning factors identified in the model, such as individual literacy, emotional responses, family support, and perceptions of disease threat by tailoring the structure and content of nursing strategies. For example, interventions that integrated self-regulation training were more responsive to patients’ emotional and cognitive barriers, addressing fear, anxiety, and maladaptive coping patterns while simultaneously promoting problem-solving and goal-setting. In contrast, DSME-focused interventions tended to prioritize knowledge acquisition and behavioral routines, which benefited individuals with adequate literacy but were less effective for those with high emotional distress or limited self-efficacy.

Across the 18 studies, supportive–educative interventions demonstrated consistent benefits in improving diabetes knowledge, self-management behavior, self-efficacy, quality of life, and glycemic outcomes. However, the degree of improvement varied, partly due to differences in intervention intensity, delivery personnel (nurse-led vs. multidisciplinary), and the extent to which emotional regulation or coping strategies were explicitly included. Four studies that incorporated self-regulation training showed particularly meaningful effects on emotional responses and coping ability, suggesting that addressing psychological processes may be a critical mechanism through which nursing systems enhance adherence and sustained self-care.

Collectively, these findings illustrate that the nursing system functions not merely as a provider of information but as an adaptive intervention mechanism that connects individual needs, emotional and cognitive processes, and behavioral demands. Its effectiveness appears strongest when interventions synthesize educational, behavioral, and emotional components rather than addressing them separately, thereby bridging the gap between self-care capacity and self-care demands within the integrative framework.

3.4.3. Coping and Appraisal Skills

In the integrative framework, Part C represents coping strategies through which individuals manage the demands of diabetes, including approach-oriented behaviors such as problem-solving, emotional regulation, and adherence to treatment routines, as well as avoidance-oriented responses [65,66,67]. The thematic synthesis of the included studies showed that coping was strengthened through three recurring patterns: improved cognitive appraisal of illness demands, enhanced emotion-focused coping, and increased problem-focused coping [10]. Interventions such as DSME, structured self-care programs, and self-regulation training contributed to these changes by improving understanding of illness, reducing diabetes-related distress, and supporting goal-setting and action planning [9].

Part D, appraisal, involves evaluating the effectiveness of these coping responses, and several studies demonstrated that better appraisal was associated with higher self-efficacy, improved adherence, and more stable emotional outcomes [24]. Although Leventhal’s Self-Regulation Model presents appraisal as occurring after coping, both IFSMT and SRM conceptualize this process as iterative, with appraisal continually shaping subsequent coping and interpretation [20]. The integration of study findings within this model indicates that enhancements in coping and appraisal are key mechanisms through which interventions facilitate more effective and sustainable diabetes self-management.

3.4.4. Outcome (Health Status and Quality of Life)

Across the included studies, two outcome themes consistently emerged: health status and quality of life. Health status was reported in all five studies and primarily assessed through glycemic indices, including fasting blood glucose levels and HbA1c, with significant improvements observed following DSME, structured self-care programs, or self-regulation training [10,14,24,34,56].

Quality of life was reported in two studies using the WHOQOL-BREF instrument and showed significant enhancement following DSME-based interventions. In addition, emotional well-being and stress reduction were reported as secondary outcomes in two studies [34,56]. Overall, the evidence indicates that interventions grounded in self-regulation principles positively influence clinical outcomes, emotional responses, and quality of life in individuals with type 2 diabetes. The integrative model derived from the reviewed literature is summarized in Table 4.

4. Discussion

This systematic review aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of self-management interventions based on the self-regulation model and to develop an integrative framework to guide future research and practice in type 2 diabetes care. Across the included studies, we found consistent evidence that both self–regulation–based approaches and structured self-management programs improve self-care behavior, self-efficacy, emotional responses, and glycemic control. At the same time, our synthesis revealed substantial overlap among the educational, behavioral, and psychological components embedded in these interventions, highlighting the need for a unified model that captures how individual, family, and systemic factors interact in the self-regulation process. The following sections interpret these findings in relation to existing literature, compare the effectiveness of intervention types, and describe how the integrative model was formulated based on the recurring constructs identified in the review.

4.1. Effectiveness of DSME Intervention

This systematic review aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of self-management interventions grounded in self-regulation principles and to map their shared mechanisms, to inform an integrative framework for future diabetes care. Overall, the evidence consistently demonstrates that DSME-based and self-regulation-based interventions improve knowledge, self-care behaviors, self-efficacy, quality of life, and glycemic outcomes in individuals with type 2 diabetes. These findings reinforce the central role of self-regulation processes, particularly goal-setting, self-monitoring, and appraisal, in shaping long-term diabetes self-management.

Diabetes Self-Management Education (DSME) emerged as a structured, evidence-based strategy that facilitates not only knowledge acquisition but also the development of skills and abilities required for sustained self-care [47]. By incorporating key self-regulation components such as goal-setting, self-monitoring, and behavioral feedback, DSME enables individuals to adjust lifestyle practices, enhance motivation, and strengthen self-awareness [9,10,68]. Thus, DSME functions not merely as an educational intervention but as a self-regulation framework that supports continued behavioral optimization.

Across the included studies, DSME interventions produced short-, medium-, and long-term positive effects on self-care knowledge and behavior [26,30,45,47,49]. Programs based on the Orem Self-Care Model and Health Belief Model also contributed to improved self-efficacy and quality of life [38,39,50]. A notable pattern was the rise of technology-assisted DSME, including video-based education, SMS-based reminders, and eHealth family education, which inherently support self-regulation through continuous goal tracking, monitoring, and feedback [31,32,35,36,37,40]. These findings are aligned with recent reviews showing that mHealth interventions facilitate sustained self-management and may serve as cost-effective behavioral tools for chronic disease management [69,70].

Although these findings demonstrate consistent improvements across DSME, SMS-based, mHealth, and family-oriented programs, the comparative pattern suggests that technology-assisted DSME tends to produce faster behavioral gains due to its higher frequency of monitoring and feedback, whereas family-oriented DSME appears more effective for emotional support and long-term adherence. Methodological variability across studies also helps explain differences in outcomes; for instance, mHealth and SMS-based interventions were often delivered with higher intensity and shorter follow-up periods, whereas family-based and in-person DSME programs typically involved longer durations and nurse-led or multidisciplinary delivery formats. These methodological differences likely contribute to the variability in glycemic and behavioral outcomes, clarifying why some studies reported stronger effects than others. Furthermore, instead of general descriptors such as “positive effect,” the evidence indicates specific outcome patterns, such as improved self-efficacy, reductions in diabetes-related distress, and measurable improvements in glycemic control, which provide a more precise understanding of the intervention’s impact.

Family-oriented DSME additionally demonstrated effectiveness in improving HbA1c, self-management behavior, and quality of life [33,36,42,44]. This aligns with broader evidence noting the importance of family support in maintaining new health behaviors and decision-making in diabetes care [71]. Importantly, our synthesis identified substantial conceptual overlap between DSME and self-regulation training interventions. Many DSME programs incorporated self-regulation mechanisms (e.g., goal-setting and monitoring), while self-regulation interventions often included educational components. This suggests that rather than being distinct approaches, DSME and self-regulation training are complementary and can be integrated using shared behavior change techniques.

Recent advances also highlight the potential of emotion regulation therapies such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), which address emotional distress, mindfulness, and adaptive coping among people with type 2 diabetes [21,22,23]. Integrating elements of ACT and DBT into DSME may strengthen patients’ psychological readiness and resilience, supporting adherence to self-care behaviors. This aligns with the growing recognition that both cognitive and affective domains are critical for achieving sustained behavior change in diabetes management.

4.2. Effectiveness of Self-Regulation Model Program Intervention

Evidence from this review indicates that interventions explicitly grounded in the self-regulation model remain limited, with only four of the 31 included studies directly examining their effects on diabetes knowledge, self-management behaviors, self-efficacy, emotional responses, quality of life, and glycemic outcomes. However, despite the small number, these studies consistently demonstrate that self-regulation-based programs can improve key self-management outcomes, particularly when delivered through structured training formats. For instance, short-term self-regulation training delivered over 3 weeks was shown to enhance diabetes self-management behaviors and glycemic control significantly [9,24].

A central mechanism underlying these improvements is the patient’s cognitive representation of diabetes, which shapes how individuals interpret symptoms, evaluate threats, and choose coping strategies. Studies included in this review support prior evidence that accurate cognitive representations are associated with better behavioral regulation and self-management performance [68,72]. Self-regulation interventions seek to strengthen these representations by helping individuals understand their condition, anticipate challenges, and adjust behavior accordingly.

Technology-assisted self-regulation programs, particularly those that use mobile health applications, represent an emerging and promising direction. These interventions emphasize autonomy, continuous monitoring, and adaptive feedback, enabling patients to develop the skills and beliefs required for sustained behavior change [73]. Evidence from one study showed substantial reductions in blood glucose levels from 162.3 mg/dL to 128.9 mg/dL following a three-week self-regulation program grounded in self-regulation theory [10], further highlighting the potential of such approaches.

Across studies, the core components of self-regulation, self-monitoring, decision-making, and behavioral adjustment were consistently associated with improved self-care outcomes [74,75,76]. However, findings also indicate that self-regulation models are most effective when combined with health education, family involvement, or supportive guidance, suggesting that cognitive–behavioral processes alone may not be sufficient to produce long-term adherence without contextual or social reinforcement [9,24]. This aligns with evidence from Egypt and other settings showing that health education enhances adherence and strengthens the behavioral foundations required for self-regulation [77].

Overall, self-regulation interventions grounded in individual and family self-management theory show considerable promise for empowering adults with type 2 diabetes to manage their condition more effectively and independently [68,78]. Given the limited number of available studies, future research should prioritize developing and testing integrated self-regulation models that combine cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and family components to optimize diabetes self-care.

4.3. New Integrative Model

The integrative model developed in this review synthesizes concepts from both self-management and self-regulation theory to offer a comprehensive framework for improving type 2 diabetes self-care [7,67]. Previous studies consistently show that self-management strategies improve clinical outcomes [79,80,81], while self-regulation theory emphasizes individuals’ capacity to monitor, evaluate, and adjust their behavior to achieve desired goals [68]. Integrating these two perspectives enables a more holistic understanding of how patients make decisions, monitor progress, and sustain long-term behavioral change [82].

Disease perception plays a central role in this process. According to the Common-Sense Model, individuals construct illness representations based on personal knowledge and experiences, shaping their appraisal and coping responses [22,23]. For people living with type 2 diabetes, accurate disease appraisal facilitates more adaptive problem-solving and self-management behavior [83]. The Individual and Family Self-Management Theory further supports this by outlining how behavioral change occurs through three interconnected pathways: the self-management process (knowledge, beliefs, and skills), proximal outcomes (self-care behaviors), and distal outcomes (quality of life) [84]. Evidence also shows that involving family in health education enhances knowledge and understanding of diabetes, treatment adherence, and glycemic outcomes [85,86,87].

To integrate findings from the included studies, we conducted a thematic synthesis that identified five recurring constructs: (1) individual self-efficacy and motivation, (2) family support and involvement, (3) patient knowledge and beliefs, (4) healthcare provider facilitation, and (5) behavior monitoring and feedback. These constructs were consistently associated with improved glycemic control and quality of life. They were subsequently mapped into an integrative model structured around three domains: context (individual, family, and healthcare system), process (knowledge, beliefs, self-monitoring, intention), and outcomes (self-care behavior and glycemic control), as shown in Figure 2. This approach ensures the model remains theoretically grounded while directly reflecting empirical patterns across studies.

Additional evidence supports the role of empowerment through education and clinician involvement as key determinants of improved dietary adherence, physical activity, and self-management performance [88,89,90]. Patients with higher self-efficacy and stronger behavioral regulation capabilities are more likely to adhere to treatment, maintain self-care routines, and achieve optimal glycemic control [91,92]. The integrative model, therefore, emphasizes that self-regulation requires an interplay among personal intention, self-efficacy, knowledge, and supportive social structures.

Despite these promising findings, this review has several limitations. A meta-analysis could not be conducted due to considerable heterogeneity in study designs, intervention modalities, age groups, and outcome measurement tools. Although the methodological appraisal using the JBI checklist was rigorous, subjective interpretation remains possible. Future reviews should incorporate post-intervention follow-up assessments to evaluate long-term sustainability better. There is also a need for more homogeneous indicators, such as standardized measures of family function, intervention type, and sample size, to strengthen comparability and validity.

Nevertheless, the current review offers several strengths. It represents one of the earliest evidence-based syntheses evaluating diabetes self-regulation interventions within individual and family contexts. It also proposes a new integrative model that may assist clinicians in designing more practical and contextually appropriate interventions by combining cognitive, behavioral, emotional, and social determinants of self-care.

In practice, this integrative model suggests that DSME programs should explicitly incorporate self-regulation components, goal-setting, self-monitoring, feedback, and coping skills training while actively involving family members to provide both emotional and practical support. Interventions lasting 8–12 weeks may be effective for initiating behavioral change, but long-term reinforcement through follow-up sessions or community support is likely necessary to sustain improvements. Incorporating advances from behavioral science, including mindfulness, acceptance, and adaptive coping strategies (e.g., ACT and DBT), may further strengthen psychological resilience and stress management.

Future research should prioritize the development and testing of structured DSME programs that embed self-regulation mechanisms and consider individual- and family-level factors such as coping responses and appraisal processes. Longitudinal studies are particularly needed to examine dynamic interactions among these variables over time. Clinicians are encouraged to integrate self-monitoring, goal-setting, action planning, and family engagement into routine diabetes counseling, while tailoring interventions to cultural and contextual needs.

Overall, the proposed integrative model advances existing theory by embedding self-regulation within a broader socioecological system. While traditional self-regulation theory concentrates on individual cognitive and behavioral processes, this model extends its scope to include family dynamics, appraisal processes, social and environmental supports, and healthcare system factors. This multidimensional orientation offers a more comprehensive and pragmatically relevant framework to guide the development of future clinical and community-based interventions for type 2 diabetes.

5. Implications for Practice

The findings of this review suggest that integrating self-regulation models into diabetes education programs can significantly improve patient autonomy, self-efficacy, and glycemic control. These results have important implications for nursing practice, particularly in community and primary care settings where nurses often serve as the primary providers of diabetes education and behavioral support. Implementing this model in clinical practice requires a coordinated multidisciplinary approach. Nurses and diabetes educators can lead structured DSME sessions and incorporate self-regulation strategies such as goal-setting, self-monitoring, feedback, and action planning.

Self-regulation-based interventions may be most beneficial when introduced early, such as at the time of diagnosis, but can also be integrated into routine follow-up visits or ongoing DSME sessions. Successful implementation requires adequate resources, including trained personnel, culturally appropriate educational materials, and digital tools that support monitoring and behavioral feedback. It is equally important to consider the role of family members, as family involvement was shown to enhance motivation, emotional support, and adherence to self-care routines. Clarifying these practical considerations, who should deliver the intervention, when it should be applied, and what resources are required provides a clearer translational pathway for integrating self-regulation strategies into routine diabetes care and aligns with the reviewer’s recommendation for deeper reflection on implementation within multidisciplinary care teams.

6. Conclusions

The findings show that interventions incorporating self-regulation components such as coping strategies, illness appraisal, goal-setting, self-monitoring, and family involvement consistently improve self-care behaviors, glycemic control, and psychosocial outcomes in individuals with type 2 diabetes.

Based on these synthesized findings, this review proposes an integrative model that connects individual, family, and healthcare system factors with the processes of self-regulation and self-management. This model highlights how personal beliefs, knowledge, self-efficacy, emotional regulation, and supportive environments interact to influence behavioral and clinical outcomes.

While the evidence demonstrates promising effectiveness, variations in study design, intervention intensity, and outcome measures limit comparability across studies. Future research should focus on validating the proposed model, standardizing key indicators, and testing comprehensive DSME programs that embed self-regulation mechanisms and account for family and contextual factors. This integrative framework offers a foundation for advancing nursing practice and guiding the development of more tailored and sustainable diabetes self-management interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: F.F. and N.U. Data curation: F.F. and E.L.S.; Methodology: F.F., N.N., E.L.S. and N.U. Writing—original draft: F.F. Writing—review & editing the final draft: F.F., N.U. and E.L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this systematic review are derived from previously published studies and publicly available databases, as cited in the manuscript. No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia, and the Faculty of Health, Mega Buana University, Palopo, for supporting this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wiebe, D.J.; Berg, C.A.; Munion, A.K.; Loyola, M.D.R.; Mello, D.; Butner, J.E.; Suchy, Y.; Marino, J.A. Executive Functioning, Daily Self-Regulation, and Diabetes Management while Transitioning into Emerging Adulthood. Ann. Behav. Med. 2023, 57, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, E.V.; Tonin, F.S.; Carneiro, J.; Pontarolo, R.; Wiens, A. Evaluation of the application of the diabetes quality of life questionnaire in patients with diabetes mellitus. J. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 64, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goins, R.T.; Jones, J.; Schure, M.; Winchester, B.; Bradley, V. Type 2 diabetes management among older American Indians: Beliefs, attitudes, and practices. Ethn. Health 2020, 25, 1055–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, R.R.; Pabón Carrasco, M.; Jiménez-Picón, N.; Ponce-Blandón, J.A. Effects of a Diabetes Self-Management Education Program on Glucose Levels and Self-Care in Type 1 Diabetes: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 16364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estuningsih, Y.; Rochmah, T.N.; Andriani, M.; Mahmudiono, T. Effect of self-regulated learning for improving dietary management and quality of life in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus at Dr. Ramelan Naval Hospital, Surabaya, Indonesia. Kesmas Natl. Public Health J. 2019, 14, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, P. Regulasi Diri Dan Dukungan Sosial Dari Keluarga Pada Pasien Diabetes Melitus Tipe 2. J. Experentia 2020, 8, 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, P.; Sawin, K.J. The Individual and Family Self-Management Theory: Background and perspectives on context, process, and outcomes. Nurs. Outlook 2009, 57, 217–225.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristoforou, E.; Lambadiari, V.; Maratou, E.; Makrilakis, K. Association of Glycemic Indices (Hyperglycemia, Glucose Variability, and Hypoglycemia) with Oxidative Stress and Diabetic Complications. J. Diabetes Res. 2020, 2020, 7489795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuman, N.; Hatamochi, C. Intervention Effect Based on Self-Regulation to Promote the Continuation of Self-Care Behavior of Patients with Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus. Health J. 2021, 13, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iawchud, N.; Rojpaisarnkit, K.; Imami, N. The application of a self-regulation model for dietary intake and exercise to control blood sugar of type II diabetic patients. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2023, 34, 570–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, H.; Phillips, L.A.; Burns, E. The Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation (CSM): A dynamic framework for understanding illness self-management. J. Behav. Med. 2016, 39, 935–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohs, K.D.; Baumeister, R.F. Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory, and Applications, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nursalam, N.; Fikriana, R.; Devy, S.R.; Ahsan, A. The development of self-regulation models based on belief in Patients with hypertension. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 1036–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariyono, H.; Romli, L.Y. Self Regulation Effect on Glycemic Control of Type 2 Diabetes Melitus Patients. Indian. J. Public. Health Res. Dev. 2020, 11, 1257–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshete, A.; Getye, B.; Aynaddis, G.; Tilaye, B.; Mekonnen, E.; Taye, B.; Zeleke, D.; Deresse, T.; Kifleyohans, T.; Assefa, Y. Association between illness perception and medication adherence in patients with diabetes mellitus in North Shoa, Zone: Cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1214725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Gao, L. Illness perceptions among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2020, 26, e12801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Xu, J.; Chen, G.; Liu, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Hao, Y.; Wu, Q.; Jiao, M. Self-management behavior and fasting plasma glucose control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus over 60 years old: Multiple effects of social support on quality of life. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogurtsova, K.; Guariguata, L.; Barengo, N.C.; Ruiz, P.L.D.; Sacre, J.W.; Karuranga, S.; Sun, H.; Boyko, E.J.; Magliano, D.J. IDF diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of undiagnosed diabetes in adults for 2021. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2022, 183, 109118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDF. IDF Diabetes Atlas Ninth edition 2020. Lancet 2021, 266, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, R.; Pise, S.; Chaudhari, L.; Deshpande, P. Evaluation of quality of life in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients using quality of life instrument for indian diabetic patients: A cross-sectional study. J. Midlife Health 2019, 10, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fassbinder, E.; Schweiger, U.; Martius, D.; Brand-de Wilde, O.; Arntz, A. Emotion regulation in schema therapy and dialectical behavior therapy. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyami, M.; Serlachius, A.; Mokhtar, I.; Broadbent, E. Longitudinal Associations Between Illness Perceptions and Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2022, 29, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chindankutty, N.V.; Devineni, D. Illness Perception, Coping, and Self-Care Adherence Among Adults With Type 2 Diabetes. J. Popul. Soc. Stud. 2024, 32, 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakolizadeh, J.; Moghadas, M.; Ashraf, H. Effect of self-regulation training on management of type 2 diabetes. Iran. Red. Crescent Med. J. 2014, 16, e13506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, H.C.; Narcisse, M.R.; Long, C.R.; Mcelfish, P.A. Effects of a Family Diabetes Self-Management Education Intervention on the Patients’ Participating Supporters Holly. Fam. Syst. Health 2020, 38, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoul, A.M.; Jalali, R.; Abdi, A.; Salari, N.; Rahimi, M.; Mohammadi, M. The effect of self-management education through weblogs on the quality of life of diabetic patients. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2019, 19, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Shin, D.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, K.S. Effect of diabetes education through pattern management on self-care and self-efficacy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathu, C.W.; Shabani, J.; Kunyiha, N.; Ratansi, R. Effect of diabetes self-management education on glycaemic control among type 2 diabetic patients at a family medicine clinic in Kenya: A randomised controlled trial. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2018, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, F.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Deng, L. Effects of an outpatient diabetes self-management education on patients with type 2 diabetes in China: A randomized controlled trial. J. Diabetes Res. 2019, 2019, 1073131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghadam, S.T.; Najafi, S.S.; Yektatalab, S. The effect of self-care education on emotional intelligence and HbA1c level in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Int. J. Community Based Nurs. Midwifery 2018, 6, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Abaza, H.; Marschollek, M. SMS education for the promotion of diabetes self-management in low & middle income countries: A pilot randomized controlled trial in Egypt. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garizábalo-Dávila, C.M.; Rodríguez-Acelas, A.L.; Mattiello, R.; Cañon-Montañez, W. Social Support Intervention for Self-Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Open Access J. Clin. Trials 2021, 13, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azami, G.; Soh, K.L.; Sazlina, S.G.; Salmiah, M.S.; Aazami, S.; Mozafari, M.; Taghinejad, H. Effect of a Nurse-Led Diabetes Self-Management Education Program on Glycosylated Hemoglobin among Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Diabetes Res. 2018, 2018, 4930157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boels, A.M.; Vos, R.C.; Dijkhorst-Oei, L.T.; Rutten, G.E.H.M. Effectiveness of diabetes self-management education and support via a smartphone application in insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes: Results of a randomized controlled trial (TRIGGER study). BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2019, 7, e000981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Mao, L.; Gu, M.; Yuan, H.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Li, X. The Effectiveness of an eHealth Family-Based Intervention Program in Patients With Uncontrolled Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) in the Community Via WeChat: Randomized Controlled. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2023, 11, e40420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusnanto Widyanata, K.A.J.; Suprajitno Arifin, H. DM-calendar app as a diabetes self-management education on adult type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled trial. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2019, 18, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Sit, J.W.H.; Choi, K.C.; Chair, S.Y.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Long, J.; Yang, H. The effects of an empowerment-based self-management intervention on empowerment level, psychological distress, and quality of life in patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 3, 103407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondhianto; Kusnanto; Melaniani, S. The effect of diabetes self-management education, based on the health belief model, on the psychosocial outcome of type 2 diabetic patients in Indonesia. Indian. J. Public. Health Res. Dev. 2018, 9, 1718–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslakpak, M.H.; Razmara, S.; Niazkhani, Z. Effects of Face-to-Face and Telephone-Based Family-Oriented Education on Self-Care Behavior and Patient Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Diabetes Res. 2017, 2017, 8404328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, S.; Yao, B.; Xu, L.; Wang, D.; Sun, J.; Yuan, N.; Ji, L. The effect of diabetes self-management education on psychological status and blood glucose in newly diagnosed patients with diabetes type 2. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 1427–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, M.M.; Pasvogel, A.; Murdaugh, C. Effects of a Family-Based Diabetes Intervention on Family Social Capital Outcomes for Mexican American Adults. Diabetes Educ. 2019, 45, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, R.; Whittaker, R.; Jiang, Y.; Maddison, R.; Shepherd, M.; McNamara, C.; Cutfield, R.; Khanolkar, M.; Murphy, R. Effectiveness of text message based, diabetes self management support programme (SMS4BG): Two arm, parallel randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2018, 361, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wichit, N.; Mnatzaganian, G.; Courtney, M.; Schulz, P.; Johnson, M. Randomized controlled trial of a family-oriented self-management program to improve self-efficacy, glycemic control and quality of life among Thai individuals with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 123, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailu, F.B.; Moen, A.; Hjortdahl, P. Diabetes Self-Management Education (DSME)—Effect on Knowledge, Self-Care Behavior, and Self-Efficacy Among Type 2 Diabetes Patients in Ethiopia: A Controlled Clinical Trial. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2019, 12, 2489–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusdiana Savira, M.; Amelia, R. The effect of diabetes self-management education on Hba1c level and fasting blood sugar in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in primary health care in binjai city of north Sumatera, Indonesia. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupa, M.F.; Lee, A.; Piette, J.D.; Trivedi, R.; Youk, A.; Heisler, M.; Rosland, A.-M. Impact of a Dyadic Intervention on Family Supporter Involvement in Helping Adults Manage Type 2 Diabetes. J. Gen Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamungkas, R.A.; Chamroonsawasdi, K. Self-management based coaching program to improve diabetes mellitus self-management practice and metabolic markers among uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus in Indonesia: A quasi-experimental study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisi GLde, M.; Aultman, C.; Konidis, R.; Foster, E.; Tahsinul, A.; Sandison, N.; Sarin, M.; Oh, P. Effectiveness of an education intervention associated with an exercise program in improving disease-related knowledge and health behaviours among diabetes patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 1790–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borji, M.; Otaghi, M.; Kazembeigi, S. The impact of Orem’s self-care model on the quality of life in patients with type II diabetes. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 2017, 10, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, C.P.; Rakkapao, N.; Hay, K. Impact of diabetes self-management, diabetes management self-efficacy and diabetes knowledge on glycemic control in people with Type 2 Diabetes (T2D): A multicenter study in Thailand. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bramer, W.M.; Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kleijnen, J.; Franco, O.H. Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: A prospective exploratory study. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, J.C.; Singh, J.; Hsieh, J.; Fehlings, M.G. Methodology of Systematic Reviews and Recommendations. J. Neurotrauma 2011, 28, 1335–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumpston, M.S.; McKenzie, J.E.; Thomas, J.; Brennan, S.E. The use of ‘PICO for synthesis’ and methods for synthesis without meta-analysis: Protocol for a survey of current practice in systematic reviews of health interventions. F1000Research 2021, 9, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monnaatsie, M.; Biddle, S.J.H.; Khan, S.; Kolbe-Alexander, T. Physical activity and sedentary behaviour in shift and non-shift workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 2021, 24, 101597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nooseisai, M.; Viwattanakulvanid, P.; Kumar, R.; Viriyautsahakul, N.; Muhammad Baloch, G.; Somrongthong, R. Effects of diabetes self-management education program on lowering blood glucose level, stress, and quality of life among females with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Thailand. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2021, 22, e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, A.; Reimer, A.; Kulzer, B.; Icks, A.; Paust, R.; Roelver, K.-M.; Kaltheuner, M.; Ehrmann, D.; Krichbaum, M.; Haak, T.; et al. Measurement of psychological adjustment to diabetes with the diabetes acceptance scale. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2018, 32, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.H.; Chen, Y.C.; Ho, C.H.; Lin, C.Y. Validation of Diabetes Knowledge Questionnaire (DKQ) in the Taiwanese Population—Concurrent Validity with Diabetes-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire Module. Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2022, 15, 2391–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toobert, D.J.; Hampson, S.E.; Glasgow, R.E. The Summary of Diabetes Self-Care. Diabetes Care J. 2000, 23, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, P.C.; Dunstan, D.W.; Larsen, R.N.; Lambert, G.W.; Kingwell, B.A.; Owen, N. Prolonged uninterrupted sitting increases fatigue in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 135, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokelainen, J.; Timonen, M.; Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi, S.; Härkönen, P.; Jurvelin, H.; Suija, K. Validation of the Zung self-rating depression scale (SDS) in older adults. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2019, 37, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) 2014. Available online: https://www.sralab.org/rehabilitation-measures/who-quality-life-bref-whoqol-bref (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Bujang, M.A.; Adnan, T.H.; Mohd Hatta, N.K.B.; Ismail, M.; Lim, C.J. A Revised Version of Diabetes Quality of Life Instrument Maintaining Domains for Satisfaction, Impact, and Worry. J. Diabetes Res. 2018, 2018, 5804687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.B.; Nguyen, T.T.; Truong, H.T.; Trinh, C.H.; Du, H.N.T.; Ngo, T.T.; Nguyen, L.H. Effects of Diabetic Complications on Health-Related Quality of Life Impairment in Vietnamese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Diabetes Res. 2020, 2020, 4360804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiqri, A.M.; Sjattar, E.L.; Irwan, A.M. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for self-care behaviors with type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A systematic review. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2022, 16, 102538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alligood, M.R. Nursing Theory Utilization & Application, 5th ed.; Mosby Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, J. Health Psychology, 4th ed.; Open University Press: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fadli, F.; Uly, N.; Safruddin, S.; Darmawan, S.; Batupadang, M. Analysis of self-regulation model to improvement of self-care capability in type 2 Diabetes Mellitus patients. Multidiscip. Sci. J. 2023, 6, 2024082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaslawi, H.; Berrou, I.; Hamid AAl Alhuwail, D.; Aslanpour, Z. Diabetes Self-management Apps: Systematic Review of Adoption Determinants and Future Research Agenda. JMIR Diabetes 2022, 7, e28153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, R.; Niakan Kalhori, S.R.; GhaziSaeedi, M.; Jeddi, M.; Nazari, M.; Fatehi, F. Mobile-based and cloud-based system for self-management of people with type 2 diabetes: Development and usability evaluation. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e18167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-W.; Tong, J. Family-Based, Culturally Responsive Intervention for Chinese Americans With Diabetes: Lessons Learned From a Literature Review to Inform Study Design and Implementation. Asian/Pac. Isl. Nurs. J. 2023, 7, e48746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motamed-Jahromi, M.; Kaveh, M.H.; Vitale, E. Mindfulness and self-regulation intervention for improved self-neglect and self-regulation in diabetic older adults. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syabariyah, S.; Putri, P.; Wardani, K.; Aisyah, P.S.; Hisan, U.K. Mobile health applications for self-regulation of glucose levels in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A systematic review. Fam. Med. Prim. Care Rev. 2024, 26, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.E.F. Self-Regulation Theory and Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose Behavior in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus; University of Louisville: Louisville, KY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukartini, T.; Nursalam, N.; Pradipta, R.O.; Ubudiyah, M. Potential Methods to Improve Self-Management in Those with Type 2 Diabetes: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 21, e119698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Sun, J.; Bian, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Dong, K.; Shen, C.; Liu, T. The relationship between hope level and self-management behaviors in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A chain-mediated role of social support and disease perception. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, M.M.; Sharaa, H.M.; Amer, F.G.M.; Shaban, M. Effect of digital based nursing intervention on knowledge of self-care behaviors and self-efficacy of adult clients with diabetes. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedini, M.; Bijari, B.; Miri, Z.; Shakhs, F.; Abbasi, A. The quality of life of the patients with diabetes type 2 using EQ-5D-5 L in Birjand. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumah, E.; Otchere, G.; Ankomah, S.E.; Fusheini, A.; Kokuro, C.; Aduo-Adjei, K.; Amankwah, J.A. Diabetes self-management education interventions in the WHO African Region: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofiani, Y.; Kamil, A.R.; Rayasari, F. The relationship between illness perceptions, self-management, and quality of life in adult with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Keperawatan Padjadjaran 2022, 10, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurmu, Y.; Dechasa, A. Effect of patient centered diabetes self care management education among adult diabetes patients in Ambo town, Ethiopia: An interventional study. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2023, 19, 100606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamiru, S.; Dugassa, M.; Amsalu, B.; Bidira, K.; Bacha, L.; Tsegaye, D. Effects of Nurse-Led diabetes Self-Management education on Self-Care knowledge and Self-Care behavior among adult patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus attending diabetes follow up clinic: A Quasi-Experimental study design. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2023, 18, 100548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyami, M.; Serlachius, A.; O’Donovan, C.E.; Werf Bvan der Broadbent, E. A systematic review of illness perception interventions in type 2 diabetes: Effects on glycaemic control and illness perceptions. Diabet Med. 2021, 38, e14495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, K.A.; Robins, J.; Salyer, J.; Thurby-Hay, L. Self and Family Management in Type 2 Diabetes: Influencing Factors and Outcomes. Nurs. Sci. Q. 2019, 32, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Staite, E.; Ismail, K.; Winkley, K. A systematic review of diabetes self-management education interventions for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Asian Western Pacific (AWP) region. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 1424–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, V.; Pazos-Couselo, M.; González-Rodríguez, M.; Rodríguez-González, R. Educational programs in type 2 diabetes designed for community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. Geriatr. Nurs. 2022, 46, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannucci, E.; Giaccari, A.; Gallo, M.; Bonifazi, A.; Belén, Á.D.P.; Masini, M.L.; Trento, M.; Monami, M. Self-management in patients with type 2 diabetes: Group-based versus individual education. A systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized trails. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2022, 32, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, S.; Rasmussen, B.; Turner, J.; Steele, C.; Ariarajah, D.; Hamblin, S.; Crowe, S.; Schutte, S.; Wynter, K.; Hussain, I.M. Nurse, midwife and patient perspectives and experiences of diabetes management in an acute inpatient setting: A mixed-methods study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, Y.; Choi, S.; Jeon, B. Evaluation of nurse-led social media intervention for diabetes self-management: A mixed-method study. J. Nurs. Sch. 2022, 54, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eghtedari, M.; Goodarzi—Khoigani, M.; Shahshahani, M.S.; Javadzade, H.; Abazari, P. Is Web-Based Program Effective on Self-Care Behaviors and Glycated Hemoglobin in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2023, 28, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Jiang, H.; Li, M.; Lu, Y.; Liu, K.; Sun, X. The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy in Shaping Self-Management Behaviors Among Adults With Type 2 Diabetes. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2019, 16, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Wang, J.; Lu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Li, M. Self-efficacy-focused education in persons with diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2019, 12, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).