Prevalence and Predictors of Positive Screening of Body Dysmorphic Disorder in Eastern Saudi Women Seeking Cosmetic Procedures: Implications for Clinical Practice in the Social Media Era

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Description

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Sampling Procedures

2.4. Data Collection Steps

2.5. Data Analysis

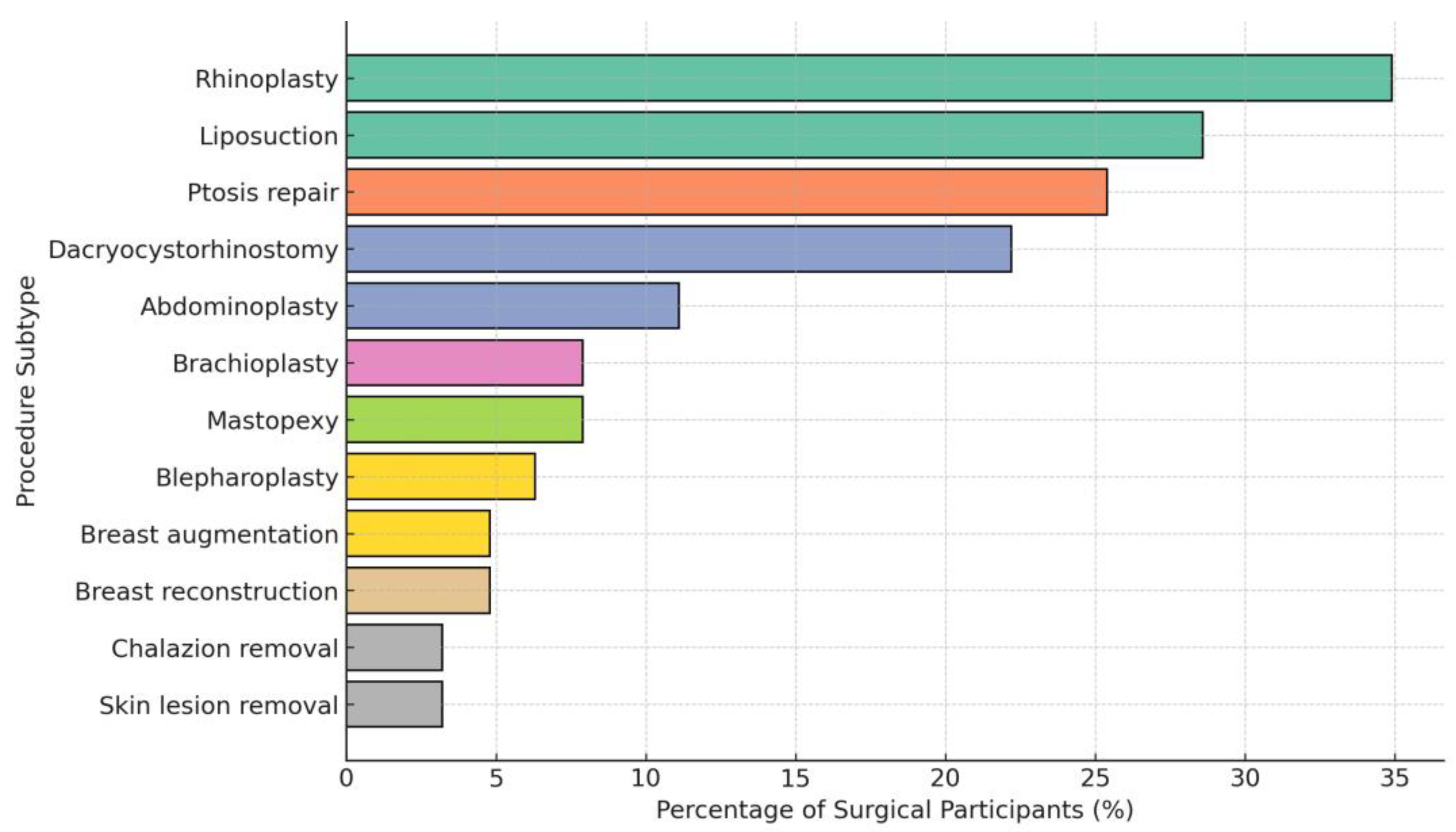

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fioravanti, G.; Bocci Benucci, S.; Ceragioli, G.; Casale, S. How the Exposure to Beauty Ideals on Social Networking Sites Influences Body Image: A Systematic Review of Experimental Studies. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2022, 7, 419–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironica, A.; Popescu, C.A.; George, D.; Tegzeșiu, A.M.; Gherman, C.D. Social Media Influence on Body Image and Cosmetic Surgery Considerations: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e65626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, K.E.; Thomas, J.R. The Changing Face of Beauty: A Global Assessment of Facial Beauty. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 53, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triana, L.; Palacios Huatuco, R.M.; Campilgio, G.; Liscano, E. Trends in Surgical and Nonsurgical Aesthetic Procedures: A 14-Year Analysis of the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery-ISAPS. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2024, 48, 4217–4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, V.M.; Diluiso, G.; Kamdem, C.J.; Goulliart, S.; Schettino, M.; Dziubek, M.; Miszewska, C.; Di Fiore, C.; Carrillo, S.O.; Delhaye, M. Demographic Study and Description of the Surgical Demand in Aesthetic Surgery. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2023, 91, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.D.; Hale, E.W.; Mundra, L.; Le, E.; Kaoutzanis, C.; Mathes, D.W. The heart of it all: Body dysmorphic disorder in cosmetic surgery. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2023, 87, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaleeny, J.D.; Janis, J.E. Body Dysmorphic Disorder in Aesthetic and Reconstructive Plastic Surgery—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicewicz, H.R.; Torrico, T.J.; Boutrouille, J.F. Body Dysmorphic Disorder. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Rück, C.; Mataix-Cols, D.; Feusner, J.D.; Shavitt, R.G.; Veale, D.; Krebs, G.; Fernández de la Cruz, L. Body dysmorphic disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2024, 10, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, R.A.; Phillips, K.A. 61Core Clinical Features of Body Dysmorphic Disorder: Appearance Preoccupations, Negative Emotions, Core Beliefs, and Repetitive and Avoidance Behaviors. In Body Dysmorphic Disorder: Advances in Research and Clinical Practice; Oxford Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, K.A.; Kelly, M.M. Body Dysmorphic Disorder: Clinical Overview and Relationship to Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Focus (Am. Psychiatr. Publ.) 2021, 19, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.E.; Redden, S.A.; Leppink, E.W.; Odlaug, B.L. Skin picking disorder with co-occurring body dysmorphic disorder. Body Image 2015, 15, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windheim, K.; Veale, D.; Anson, M. Mirror gazing in body dysmorphic disorder and healthy controls: Effects of duration of gazing. Behav. Res. Ther. 2011, 49, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addison, M.; James, A.; Borschmann, R.; Costa, M.; Jassi, A.; Krebs, G. Suicidal thoughts and behaviours in body dysmorphic disorder: Prevalence and correlates in a sample of mental health service users in the UK. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 361, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, R.F.; Alrahmani, D.A.; Ahmed, D.M.; Alharthi, N.A.; Fida, A.R.; Al-Raddadi, R.M. Association of body dysmorphic disorder with anxiety, depression, and stress among university students. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2021, 16, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shuhayb, Z.S. Prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder among Saudis seeking facial plastic surgery. Saudi Surg. J. 2019, 7, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwer, D.B.; Spitzer, J.C. Body Image Dysmorphic Disorder in Persons Who Undergo Aesthetic Medical Treatments. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2012, 32, 999–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, S.; Wysong, A. Cosmetic Surgery and Body Dysmorphic Disorder—An Update. Int. J. Womens Dermatol. 2018, 4, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Kazeminia, M.; Heydari, M.; Darvishi, N.; Ghasemi, H.; Shohaimi, S.; Mohammadi, M. Body dysmorphic disorder in individuals requesting cosmetic surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2022, 75, 2325–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiotsa, B.; Naccache, B.; Duval, M.; Rocher, B.; Grall-Bronnec, M. Social Media Use and Body Image Disorders: Association between Frequency of Comparing One’s Own Physical Appearance to That of People Being Followed on Social Media and Body Dissatisfaction and Drive for Thinness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanzari, C.M.; Gorrell, S.; Anderson, L.M.; Reilly, E.E.; Niemiec, M.A.; Orloff, N.C.; Anderson, D.A.; Hormes, J.M. The impact of social media use on body image and disordered eating behaviors: Content matters more than duration of exposure. Eat. Behav. 2023, 49, 101722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoli, M.; Scotto Rosato, M.; Desousa, A.; Cotrufo, P. Cultural Differences in Body Image: A Systematic Review. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conboy, L.; Mingoia, J.; Hutchinson, A.D.; Reisinger, B.A.A.; Gleaves, D.H. Digital body image interventions for adult women: A meta-analytic review. Body Image 2024, 51, 101776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashmar, M.; Alsufyani, M.A.; Ghalamkarpour, F.; Chalouhi, M.; Alomer, G.; Ghannam, S.; El Minawi, H.; Saedi, B.; Hunter, N.; Alkobaisi, A.; et al. Consensus Opinions on Facial Beauty and Implications for Aesthetic Treatment in Middle Eastern Women. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2019, 7, e2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Aibi, A.R.; Ismail, M. The Cultural Evolution and Social Pressures of Liposuction Among Iraqi Women: Navigating Modern Beauty Standards Amidst Conservative Traditions. Cureus 2024, 16, e61440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldeham, R.K.; Bin Abdulrahman, K.; Habib, S.K.; Alajlan, L.M.; AlSugayer, M.K.; Alabdulkarim, L.H. Public Views About Cosmetic Procedures in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2023, 15, e50135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calculator.net. Sample Size Calculator. Available online: https://www.calculator.net/sample-size-calculator.html (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Mortada, H.; Seraj, H.; Bokhari, A. Screening for body dysmorphic disorder among patients pursuing cosmetic surgeries in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2020, 41, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ateq, K.; Alhajji, M.; Alhusseini, N. The association between use of social media and the development of body dysmorphic disorder and attitudes toward cosmetic surgeries: A national survey. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1324092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rammal, A.; Bukhari, J.S.; Alsharif, G.N.; Aseeri, H.S.; Alkhamesi, A.A.; Alharbi, R.F.; Almohammadi, W.F. High Prevalence of Body Dysmorphic Disorder Among Rhinoplasty Candidates: Insights From a Cross-Sectional Study in Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2024, 16, e76431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, A.; Piroozi, B.; Safari, H.; Shokri, A.; Aqaei, A.; Yousefi, F.; Nikouei, M.; Rafieemovahhed, M. Prevalence of elective cosmetic surgery and its relationship with socioeconomic and mental health: A cross-sectional study in west of Iran. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, E.X.; Green, A.; Kandathil, C.K.; Most, S.P. Increased Prevalence of Positive Body Dysmorphic Disorder Screening Among Rhinoplasty Consultations During the COVID-19 Era. Facial Plast. Surg. Aesthetic Med. 2023, 26, 584–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshidi, R.; Hammouri, M.; Al-Ani, A.; Kitaneh, R.; Al-Soleiti, M.; Al Ta’ani, Z.; Sweis, S.; Halasa, Z.; Fashho, E.; Arafah, M.; et al. Investigating the prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder among Jordanian adults with dermatologic and cosmetic concerns: A case–control study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Taleb, R.; Hannani, H.; Mojiri, M.E.; Mobarki, O.A.; Daghriri, S.A.; Mosleh, A.A.; Mongri, A.O.; Farji, J.S.; Alzahrani, A.A.; Safhi, A.M.; et al. Prevalence and Patterns of Cosmetic Dermatological Procedures in Jazan, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2024, 16, e71223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sindi, E.E.; Shosho, R.Y.; AlSulami, M.A.; Alghamdi, A.A.; Alnemari, M.D.; Felemban, W.H.; Aljindan, F.; Alharbi, M.; Altamimi, L.; Almajnuni, R.S. Factors That Affect the Likelihood of Undergoing Cosmetic Procedures Among the General Population of Western Region, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e49792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlBahlal, A.; Alosaimi, N.; Bawadood, M.; AlHarbi, A.; AlSubhi, F. The Effect and Implication of Social Media Platforms on Plastic Cosmetic Surgery: A Cross-sectional Study in Saudi Arabia From 2021 to 2022. Aesthetic Surg. J. Open Forum 2023, 5, ojad002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albash, L.A.; Alyahya, T.; Albooshal, S.S.; Busbait, S.A.; Alkhateeb, A.K.; Alturaiki, B.Y. Social Media Influencers and Their Impact on Society in Performing Cosmetic Procedures Among Al-Ahsa Community. Cureus 2024, 16, e68374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salameh, R.; Ghadban, E.; Murr, E.E.; Hanna, C. Influence of social media on the intent to undergo cosmetic facial injections among Lebanese university students. BMC Digit. Health 2025, 3, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, C.E.; Krumhuber, E.G.; Dayan, S.; Furnham, A. Effects of social media use on desire for cosmetic surgery among young women. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 3355–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlShahwan, M.A. Prevalence and characteristics of body dysmorphic disorder in Arab dermatology patients. Saudi Med. J. 2020, 41, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, E.X.; Kimura, K.S.; Abdelhamid, A.S.; Abany, A.E.; Losorelli, S.; Green, A.; Kandathil, C.K.; Most, S.P. Prevalence and Characteristics Associated with Positive Body Dysmorphic Disorder Screening Among Patients Presenting for Cosmetic Facial Plastic Surgery. Facial Plast. Surg. Aesthet. Med. 2024, 26, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldukhi, S.A.; Almukhadeb, E.A. Prevalence of Body Dysmorphic Disorder Among Dermatology and Plastic Surgery Patients in Saudi Arabia and its Association with Cosmetic Procedures. Bahrain Med. Bull. 2021, 43, 403–409. [Google Scholar]

- Al Shuhayb, B.S.; Bukhamsin, S.; Albaqshi, A.A.; Omer Mohamed, F. The Prevalence and Clinical Features of Body Dysmorphic Disorder Among Dermatology Patients in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2023, 15, e42474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berjaoui, A.; Chahine, B. Body dysmorphic disorder among Lebanese females: A cross-sectional study. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, T.A.; Althagafi, E.S.; Alsofiani, M.H.; Alasmari, R.M.; Aljehani, M.K.; Taha, A.A.; Mahfouz, M.E.M. Perception Toward Cosmetic Surgeries Among Adults in Saudi Arabia and Its Associated Factors: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2024, 6, e64338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szászi, B.; Szabó, P. The prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder and the acceptance of cosmetic surgery in a nonclinical sample of Hungarian adults. Mentálhigiéné Pszichoszomatika 2024, 25, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losorelli, S.; Kandathil, C.K.; Saltychev, M.; Wei, E.X.; Rossi-Meyer, M.K.; Most, S.P. Association Between Symptoms of Body Dysmorphia and Social Media Usage: A Cross-Generational Comparison. Facial Plast. Surg. Aesthetic Med. 2025, 27, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Less than 25 years | 107 | 42.8 |

| 26 to 40 years | 120 | 48.0 |

| More than 40 Years | 23 | 9.2 |

| Work Status | ||

| Unemployed | 68 | 27.2 |

| Government employee | 69 | 27.6 |

| Private sector employee | 48 | 19.2 |

| Self-employed | 65 | 26.0 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 131 | 52.4 |

| Married | 82 | 32.4 |

| Divorce/widowed | 38 | 15.2 |

| Education level | ||

| Up to high school | 81 | 32.4 |

| University and above | 169 | 67.6 |

| Monthly income | ||

| Less than 5000 SAR | 48 | 14.4 |

| 5000 to 10,000 SAR | 105 | 32.4 |

| More than 10,000 SAR | 97 | 53.2 |

| Smoking status | ||

| No | 217 | 86.8 |

| Yes | 33 | 13.2 |

| Chronic disease | ||

| No | 164 | 65.6 |

| Yes | 86 | 34.4 |

| Variable | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Have you ever visited a consultant or clinic for plastic surgery before? | ||

| No | 174 | 69.6 |

| Yes | 76 | 30.4 |

| Have you undergone any cosmetic surgery? | ||

| No | 187 | 74.8 |

| Yes | 63 | 25.2 |

| Are you considering undergoing a cosmetic procedure to correct a defect during this visit? | ||

| No | 160 | 64.0 |

| Yes | 90 | 36.0 |

| Variable | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Hours per day spent on social media | ||

| Less than 1 h | 45 | 18.0 |

| 1–3 h | 95 | 38.0 |

| More than 3 h | 110 | 44.0 |

| Social media platforms * | ||

| 180 | 72.0 | |

| Snapchat | 150 | 60.0 |

| TikTok | 138 | 55.2 |

| Twitter (X) | 85 | 34.0 |

| 55 | 22.0 | |

| Other | 20 | 8.0 |

| Exposed to cosmetic-procedure content on social media | ||

| Yes | 170 | 68.0 |

| No | 80 | 32.0 |

| Social media influenced the decision to undergo a cosmetic procedure | ||

| Yes | 72 | 28.8 |

| No | 123 | 49.2 |

| Not sure | 55 | 22.0 |

| Beauty filters or social media trends cause dissatisfaction | ||

| Never | 35 | 14.0 |

| Rarely | 58 | 23.2 |

| Sometimes | 85 | 34.0 |

| Frequently | 50 | 20.0 |

| Always | 22 | 8.8 |

| Variable | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Are you highly concerned about the appearance of any part(s) of your body that you believe look unattractive? (BDD-Q1) | ||

| No | 58 | 23.2 |

| Yes | 192 | 76.8 |

| Do these appearance-related concerns often occupy your thoughts to the extent that you wish you could think about them less? (BDD-Q2) | ||

| No | 77 | 30.8 |

| Yes | 173 | 69.2 |

| Have other people ever commented on or pointed out the area(s) of your appearance that concern you? (BDD-Q3) | ||

| No | 138 | 55.2 |

| Yes | 112 | 44.8 |

| Have these perceived defects caused you considerable distress, discomfort, or emotional pain? (BDD-Q4) | ||

| No | 145 | 58.0 |

| Yes | 105 | 42.0 |

| Have these concerns noticeably interfered with your social relationships or social activities? (BDD-Q5) | ||

| No | 194 | 77.6 |

| Yes | 56 | 22.4 |

| Have your appearance-related worries affected your schoolwork, job performance, or ability to fulfill your daily responsibilities? (BDD-Q6) | ||

| No | 186 | 74.4 |

| Yes | 64 | 25.6 |

| On average, how much time per day do you spend thinking about the part(s) of your appearance that concern you? (BDD-Q7) | ||

| Less than 1 h a day | 146 | 58.4 |

| 1 to 3 h a day | 64 | 25.6 |

| More than 3 h a day | 40 | 16.0 |

| Variables | Total n = 250 | Multivariable Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No n = 178 | Yes n = 72 | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

| Age | ||||||

| Less than 25 years | 107 | 65 | 42 | Ref | ||

| 26 to 40 years | 120 | 96 | 24 | 0.341 | 0.212–0.517 | 0.008 |

| More than 40 years | 23 | 17 | 6 | 0.632 | 0.481–0.831 | 0.019 |

| Work Status | ||||||

| Unemployed | 68 | 49 | 19 | Ref | ||

| Government employee | 69 | 48 | 21 | 1.252 | 0.371–4.220 | 0.717 |

| Private sector employee | 48 | 34 | 14 | 1.950 | 0.672–5.663 | 0.219 |

| Self-employed | 65 | 47 | 18 | 2.152 | 0.639–7.246 | 0.216 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 131 | 96 | 35 | Ref | ||

| Married | 81 | 53 | 28 | 2.717 | 0.493–14.986 | 0.251 |

| Divorce/widowed | 38 | 29 | 9 | 1.593 | 0.353–7.186 | 0.545 |

| Education level | ||||||

| Up to high school | 81 | 63 | 18 | Ref | ||

| University and above | 169 | 115 | 54 | 1.291 | 1.016–1.667 | 0.038 |

| Monthly income | ||||||

| Less than 5000 SAR | 48 | 35 | 13 | Ref | ||

| 5000 to 10,000 SAR | 105 | 72 | 33 | 0.666 | 0.253–1.755 | 0.411 |

| More than 10,000 SAR | 97 | 71 | 26 | 0.836 | 0.373–1.870 | 0.662 |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| No | 217 | 157 | 60 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 33 | 21 | 12 | 0.598 | 0.264–1.356 | 0.218 |

| Chronic diseases | ||||||

| No | 209 | 147 | 62 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 41 | 31 | 10 | 1.637 | 0.723–3.705 | 0.237 |

| Considering a cosmetic procedure during this visit | ||||||

| No | 160 | 140 | 20 | Ref | 1.671–4.982 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 90 | 38 | 52 | 3.123 | ||

| Social media use duration | ||||||

| Less than 1 h | 45 | 40 | 5 | Ref | ||

| 1 to 3 h | 95 | 75 | 20 | 0.872 | 0.731–3.04 | 0.281 |

| More than 3 h | 110 | 63 | 47 | 4.368 | 3.570–5.134 | 0.007 |

| Prior cosmetic surgery history | ||||||

| No | 187 | 142 | 45 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 63 | 36 | 27 | 3.902 | 1.719–6.284 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alenezi, A.M.; AlQahtani, B.A.M.; Thirunavukkarasu, A.; Alrashed, H.; Alsardi, B.A.H.; Aldaham, T.A.B.; Alsabilah, R.M.D.; Alazmi, K.N.N. Prevalence and Predictors of Positive Screening of Body Dysmorphic Disorder in Eastern Saudi Women Seeking Cosmetic Procedures: Implications for Clinical Practice in the Social Media Era. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3232. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243232

Alenezi AM, AlQahtani BAM, Thirunavukkarasu A, Alrashed H, Alsardi BAH, Aldaham TAB, Alsabilah RMD, Alazmi KNN. Prevalence and Predictors of Positive Screening of Body Dysmorphic Disorder in Eastern Saudi Women Seeking Cosmetic Procedures: Implications for Clinical Practice in the Social Media Era. Healthcare. 2025; 13(24):3232. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243232

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlenezi, Anfal Mohammed, Bandar Abdulrahman Mansour AlQahtani, Ashokkumar Thirunavukkarasu, Hatim Alrashed, Boshra Abdullrahma H. Alsardi, Tamam Abdulrahman B. Aldaham, Rahmah Mohammed D. Alsabilah, and Khulud Najeh N. Alazmi. 2025. "Prevalence and Predictors of Positive Screening of Body Dysmorphic Disorder in Eastern Saudi Women Seeking Cosmetic Procedures: Implications for Clinical Practice in the Social Media Era" Healthcare 13, no. 24: 3232. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243232

APA StyleAlenezi, A. M., AlQahtani, B. A. M., Thirunavukkarasu, A., Alrashed, H., Alsardi, B. A. H., Aldaham, T. A. B., Alsabilah, R. M. D., & Alazmi, K. N. N. (2025). Prevalence and Predictors of Positive Screening of Body Dysmorphic Disorder in Eastern Saudi Women Seeking Cosmetic Procedures: Implications for Clinical Practice in the Social Media Era. Healthcare, 13(24), 3232. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243232