Individual Health Management (IHM) for Stress—A Randomised Controlled Trial (TALENT II Study)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

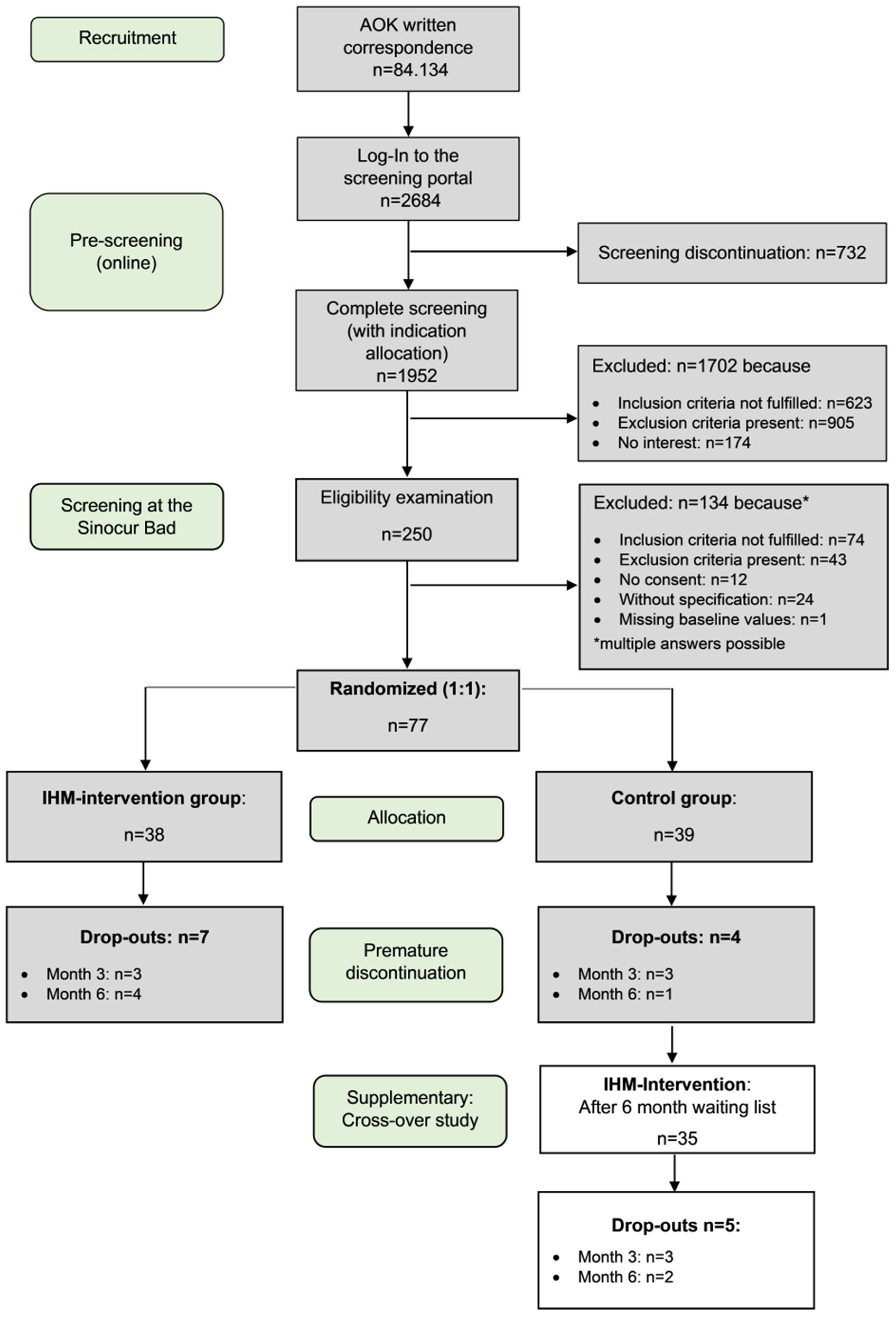

2.2. Recruitment, Randomisation and Participants

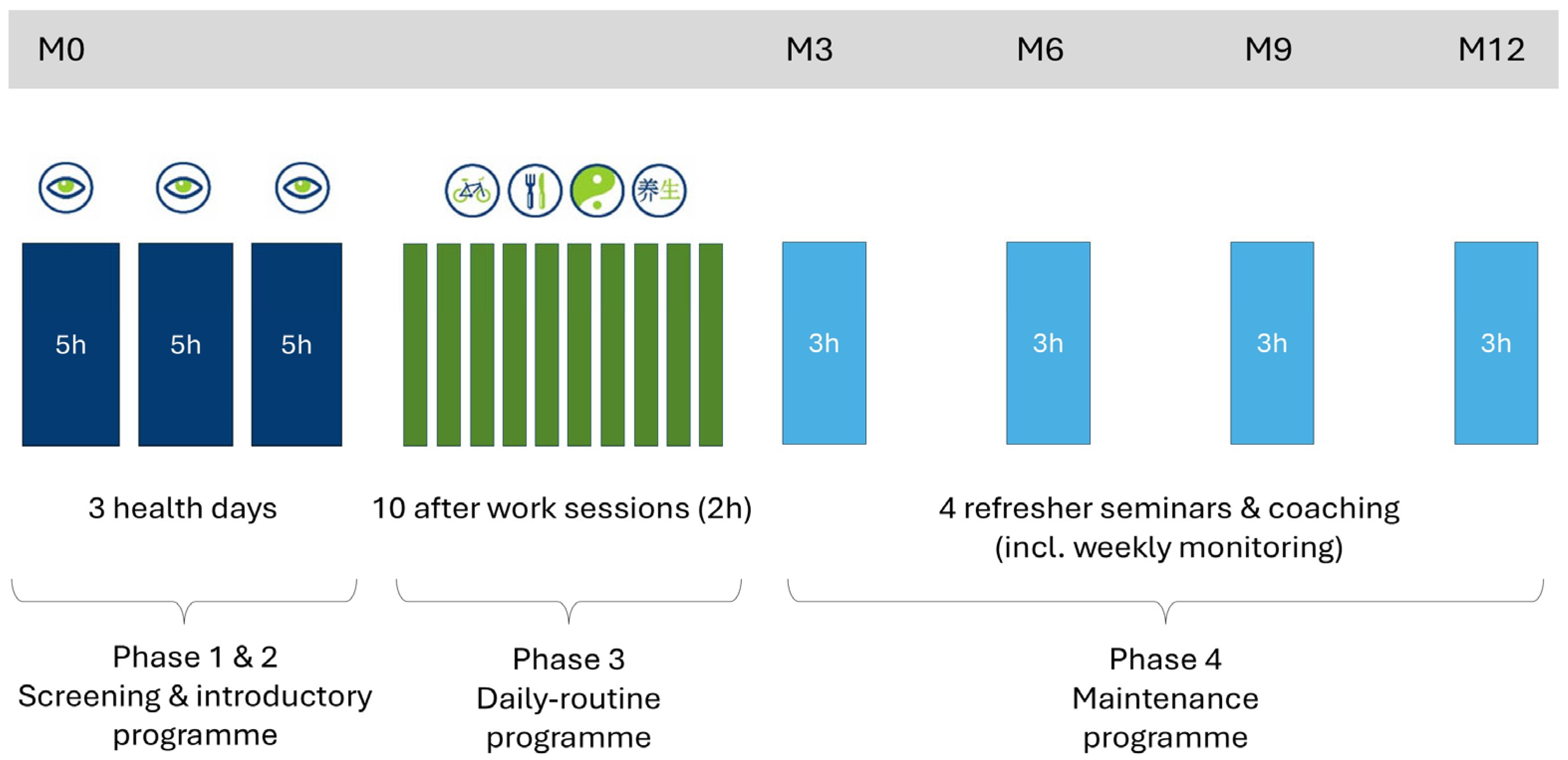

2.3. Intervention

2.4. Outcomes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Dropout and Missing Data

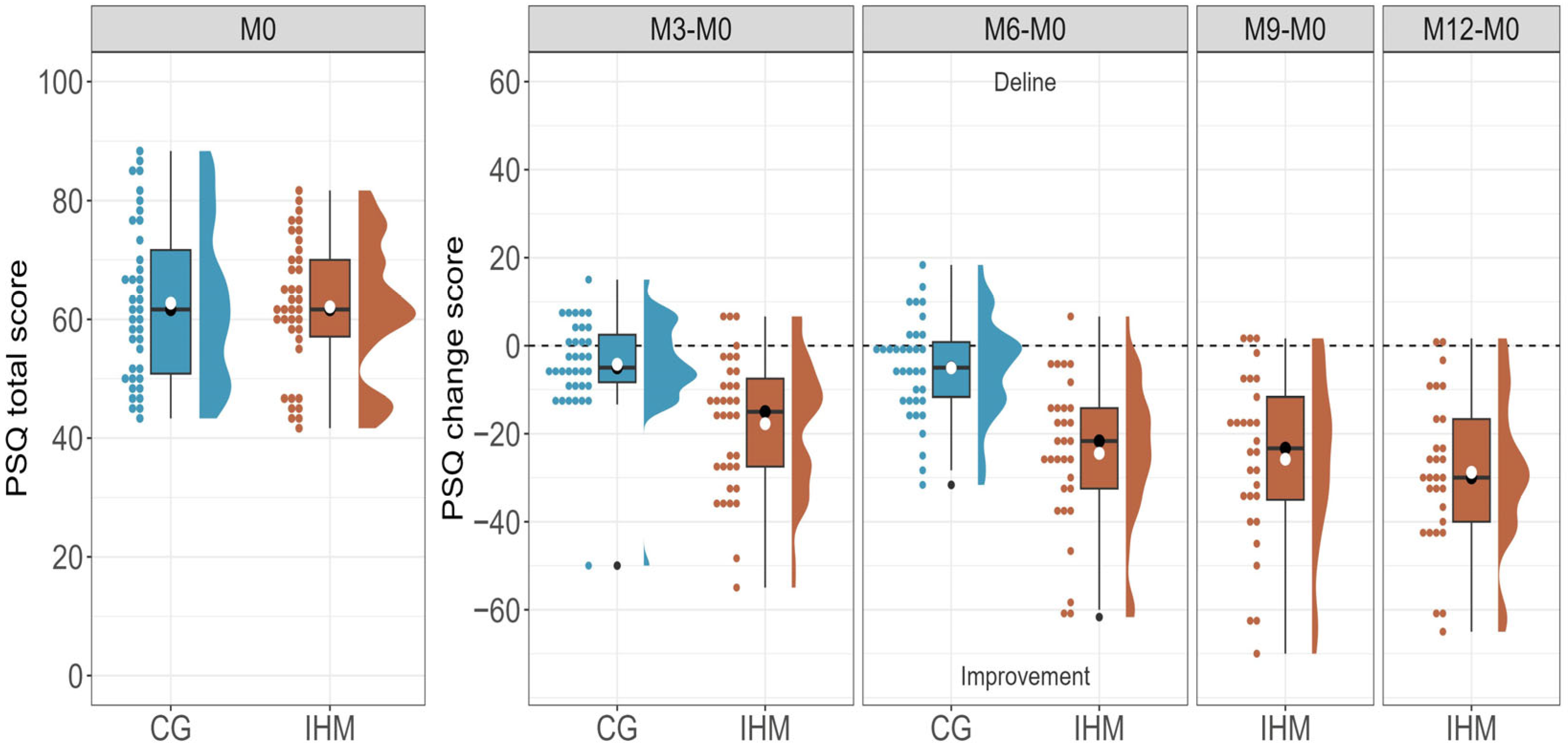

3.3. Primary Outcome

3.4. PSQ Subscales

3.5. Analysis of Covariance

3.6. Cross-Over Analysis

3.7. Secondary Outcomes

3.8. Stress Profile

3.9. Mental Stress and Burden

3.10. Psychological Resource Profile

3.11. General Mood State Severity (VAS)

3.12. Adverse Events

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOK | Allgemeine Ortskrankenkasse—General Health Insurance, Bavaria |

| CoCoNat | The Competence Center for Complementary Medicine and Naturopathy |

| IHM | Individual Health Management |

| ILI | Intensive Lifestyle Intervention |

| TALENT | TAilored Lifestyle IntervENTion Study |

| VITERIO | VIrtual Tool for Education, Reporting, Information and Outcomes |

References

- Wanni Arachchige Dona, S.; McKenna, K.; Ho, T.Q.A.; Bohingamu Mudiyanselage, S.; Seymour, M.; Le, H.N.D.; Gold, L. Health-related quality of life, service utilisation and costs for anxiety disorders in children and young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2025, 373, 118023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohls, J.K.; König, H.-H.; Quirke, E.; Hajek, A. Anxiety, Depression and Quality of Life—A Systematic Review of Evidence from Longitudinal Observational Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Jha, S.C.; Shutta, K.H.; Huang, T.; Balasubramanian, R.; Clish, C.B.; Hankinson, S.E.; Kubzansky, L.D. Psychological distress and metabolomic markers: A systematic review of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and subclinical distress. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 143, 104954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hahad, O.; Kerahrodi, J.G.; Brähler, E.; Lieb, K.; Gilan, D.; Zahn, D.; Petrowski, K.; Reinwarth, A.C.; Kontohow-Beckers, K.; Schuster, A.K.; et al. Psychological resilience, cardiovascular disease, and mortality—Insights from the German Gutenberg Health Study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2025, 192, 112116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, W.; Wei, Y.-H.; Zhang, X.-S.; Zhu, Y.; Li, X.-H. Perceived stress, risk factors and prognostic monitoring loci for the development of depression. World J. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 105222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, M.; Wang, H.F.W.; McNaughton, S.A.; Thomas, G.; Firth, J.; Trott, M.; Cairney, J. Clusters of healthy lifestyle behaviours are associated with symptoms of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2025, 118, 102585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, J.; Waibl, P.J.; Meissner, K. Stress reduction through taiji: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2024, 24, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wankhar, D.; Prabu Kumar, A.; Vijayakumar, V.; Arumugam, V.; Balakrishnan, A.; Ravi, P.; Rudra, B.K.M. Effect of Meditation, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, and Relaxation Techniques as Mind-Body Medicine Practices to Reduce Blood Pressure in Cardiac Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus 2024, 16, e58434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Webster, K.E.; Halicka, M.; Bowater, R.J.; Parkhouse, T.; Stanescu, D.; Punniyakotty, A.V.; Savović, J.; Huntley, A.; Dawson, S.; E Clark, C.; et al. Effectiveness of stress management and relaxation interventions for management of hypertension and prehypertension: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ Med. 2025, 4, e001098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng-Gyasi, E.; Parker, S. Combined Effects of Social and Behavioral Factors on Stress and Depression. Diseases 2025, 13, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hives, B.A.; Beauchamp, M.R.; Liu, Y.; Weiss, J.; Puterman, E. Multidimensional correlates of psychological stress: Insights from traditional statistical approaches and machine learning using a nationally representative Canadian sample. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0323197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, J.; Solmi, M.; Wootton, R.E.; Vancampfort, D.; Schuch, F.B.; Hoare, E.; Gilbody, S.; Torous, J.; Teasdale, S.B.; Jackson, S.E.; et al. A meta-review of “lifestyle psychiatry”: The role of exercise, smoking, diet and sleep in the prevention and treatment of mental disorders. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 360–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, S.; Mahmood, N.; Javaid, S.F.; Khan, M.A.B. The Effect of Lifestyle Interventions on Anxiety, Depression and Stress: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, G.; Fagundes, C.P. (Eds.) Lifestyle Psychiatry: Through the Lens of Behavioral Medicine; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi, F.; Beversdorf, D.Q.; Herman, K.C. Stress and stress responses: A narrative literature review from physiological mechanisms to intervention approaches. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 2024, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, W.; Manger, S.H.; Blencowe, M.; Murray, G.; Ho, F.Y.-Y.; Lawn, S.; Blumenthal, J.A.; Schuch, F.; Stubbs, B.; Ruusunen, A.; et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of lifestyle-based mental health care in major depressive disorder: World Federation of Societies for Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) and Australasian Society of Lifestyle Medicine (ASLM) taskforce. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 24, 333–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimundo, M.; Cerqueira, A.; Gaspar, T.; Gaspar de Matos, M. An Overview of Health-Promoting Programs and Healthy Lifestyles for Adolescents and Young People: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- EveryDay Actions for Better Health—WHO Recommendations. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/everyday-actions-for-better-health-who-recommendations (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Melchart, D.; Löw, P.; Wühr, E.; Kehl, V.; Weidenhammer, W. Effects of a tailored lifestyle self-management intervention (TALENT) study on weight reduction: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2017, 10, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melchart, D.; Eustachi, A.; Wellenhofer-Li, Y.; Doerfler, W.; Bohnes, E. Individual Health Management—A Comprehensive Lifestyle Counselling Programme for Health Promotion, Disease Prevention and Patient Education. Forsch Komplementmed 2016, 23, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchart, D.; Wühr, E.; Doerfler, W.; Eustachi, A.; Wellenhofer-Li, Y.; Weidenhammer, W. Introduction of a web portal for an Individual Health Management and observational health data sciences. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 2018, 9, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melchart, D.; Wühr, E.; Doerfler, W.; Eustachi, A.; Wellenhofer-Li, Y.; Weidenhammer, W. Preliminary outcome data of a Sino-European-Prevention-Program (SEPP) in individuals with perceived stress. J. Prev. Med. Healthc. 2017, 1, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchart, D.; Wühr, E.; Wifling, K.; Bachmeier, B.E. The TALENT II study: A randomized controlled trial assessing the impact of an individual health management (IHM) on stress reduction. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pines, A.; Aronson, E.; Kafry, D. Burnout: From Tedium to Personal Growth; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Tritt, K.; Heymann, F.; Zaudig, M.; Zacharias, I.; Söllner, W.; Loew, T. Entwicklung des Fragebogens “ICD-10-Symptom-Rating” (ISR) [Development of the “ICD-10-Symptom-Rating” (ISR) questionnaire]. Z. Für Psychosom. Med. Und Psychother. 2008, 54, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topp, C.W.; Østergaard, S.D.; Søndergaard, S.; Bech, P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015, 84, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholler, G.; Fliege, H.; Klapp, B.F. Fragebogen zu Selbstwirksamkeit, Optimismus und Pessimismus: Restrukturierung, Itemselektion und Validierung eines Instruments an Untersuchungen klinischer Stichproben [Questionnaire of self-efficacy, optimism and pessimism: Reconstruction, selection of items and validation of an instrument by means of examinations of clinical samples]. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 1999, 49, 275–283. [Google Scholar]

- Feldt, T.; Lintula, H.; Suominen, S.; Koskenvuo, M.; Vahtera, J.; Kivimäki, M. Structural validity and temporal stability of the 13-item sense of coherence scale: Prospective evidence from the population-based HeSSup study. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, G.; Herschbach, P. Questions on Life Satisfaction (FLZM)—A Short Questionnaire for Assessing Subjective Quality of Life. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2000, 16, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.S.; McCabe, G.P.; Craig, B.A. Introduction to the Practice of Statistics, 8th ed.; W. H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, S.; Irizar, P.; Greenberg, N.; Wessely, S.; Fear, N.T.; Hotopf, M.; Stevelink, S.A.M. Sickness absence and associations with sociodemographic factors, health risk behaviours, occupational stressors and adverse mental health in 40,343 UK police employees. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2024, 33, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, S.; Deguchi, Y.; Okura, S.; Maekubo, K.; Inoue, K. Quantifying the impact of occupational stress on long-term sickness absence due to mental disorders. Work 2025, 80, 1137–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsäter, E.; Axelsson, E.; Salomonsson, S.; Santoft, F.; Ejeby, K.; Ljótsson, B.; Åkerstedt, T.; Lekander, M.; Hedman-Lagerlöf, E. Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Stress: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychother. Psychosom. 2018, 87, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennerstam, V.; Franke Föyen, L.; Kontio, E.; Svärdman, F.; Lekander, M.; Lindsäter, E.; Hedman-Lagerlöf, E. Internet-Delivered Treatment for Stress-Related Disorders: A Randomized Controlled Superiority Trial of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy versus General Health Promotion. Psychother. Psychosom. 2025, 94, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, C.; Meixner, F.; Wiebking, C.; Gilg, V. Regular Physical Activity, Short-Term Exercise, Mental Health, and Well-Being Among University Students: The Results of an Online and a Laboratory Study. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebar, A.L.; Stanton, R.; Geard, D.; Short, C.; Duncan, M.J.; Vandelanotte, C. A meta-meta-analysis of the effect of physical activity on depression and anxiety in non-clinical adult populations. Health Psychol. Rev. 2015, 9, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacka, F.N.; Cherbuin, N.; Anstey, K.J.; Butterworth, P. Dietary patterns and depressive symptoms over time: Examining the relationships with socioeconomic position, health behaviours and cardiovascular risk. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórez, K.R.; Dubowitz, T.; Ghosh-Dastidar, M.B.; Beckman, R.; Collins, R.L. Associations between depressive symptomatology, diet, and body mass index among participants in the supplemental nutrition assistance program. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 1102–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Li, J.; Ye, J.; Luo, X.; Wilson, A.; Mu, L.; Zhou, P.; Lv, Y.; Wang, Y. Mapping associations between anxiety and sleep problems among outpatients in high-altitude areas: A network analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crabb, A.B.; Allen, J.; Taylor, G. What if I fail? Unsuccessful smoking cessation attempts and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e091419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, R.K.; Magan, D.; Mehta, N.; Sharma, R.; Mahapatra, S.C. Efficacy of a short-term yoga-based lifestyle intervention in reducing stress and inflammation: Preliminary results. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2012, 18, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daubenmier, J.J.; Weidner, G.; Sumner, M.D.; Mendell, N.; Merritt-Worden, T.; Studley, J.; Ornish, D. The contribution of changes in diet, exercise, and stress management to changes in coronary risk in women and men in the multisite cardiac lifestyle intervention program. Ann. Behav. Med. 2007, 33, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpoveta, E.D.; Okpete, U.E.; Byeon, H. Sleep disorders and mental health: Understanding the cognitive connection. World J. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 105362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinsley, J.; O’Connor, E.J.; Singh, B.; McKeon, G.; Curtis, R.; Ferguson, T.; Gosse, G.; Willems, I.; Marent, P.-J.; Szeto, K.; et al. Effectiveness of Digital Lifestyle Interventions on Depression, Anxiety, Stress, and Well-Being: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e56975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, Y.-S.; Ow Yong, Q.Y.J.; Tam, W.-S.W. Effects of online stigma-reduction programme for people experiencing mental health conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 1040–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ierardi, E.; Bottini, M.; Riva Crugnola, C. Effectiveness of an online versus face-to-face psychodynamic counselling intervention for university students before and during the COVID-19 period. BMC Psychol. 2022, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karyotaki, E.; Efthimiou, O.; Miguel, C.; Bermpohl, F.M.G.; Furukawa, T.A.; Cuijpers, P.; Riper, H.; Patel, V.; Mira, A.; Gemmil, A.W.; et al. Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression: A Systematic Review and Individual Patient Data Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

= Yang Sheng).

= Yang Sheng).

= Yang Sheng).

= Yang Sheng).

| Intervention Group (n = 38) | Control Group (n = 39) | Between Group Differences | In Total (n = 77) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p | Mean | SD | |

| Age (years) | 44.32 | 10.05 | 45.18 | 11.35 | 0.725 | 44.75 | 10.67 |

| n | % | n | % | p | n | % | |

| Female | 29 | 76.3 | 35 | 89.7 | <0.001 *** | 64 | 83.1 |

| Male | 9 | 23.7 | 4 | 10.3 | 13 | 16.9 | |

| School education | 0.529 | ||||||

| No school-leaving certificate | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.6 | 1 | 1.3 | |

| Secondary general school certificate | 15 | 40.5 | 11 | 28.2 | 26 | 34.2 | |

| Intermediate school certificate | 15 | 40.5 | 19 | 48.7 | 34 | 44.7 | |

| University entrance qualification | 6 | 16.2 | 8 | 20.5 | 14 | 18.4 | |

| Other degree | 1 | 2.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.3 | |

| Vocational education | 0.207 | ||||||

| No completed vocational training | 4 | 10.8 | 4 | 10.3 | 8 | 10.5 | |

| Completed apprenticeship | 23 | 62.2 | 18 | 46.2 | 41 | 54.0 | |

| Vocational School | 7 | 18.9 | 11 | 28.2 | 18 | 23.7 | |

| University of applied science | 1 | 2.7 | 3 | 7.7 | 4 | 5.3 | |

| University degree | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 5.1 | 2 | 2.6 | |

| Other degree | 2 | 5.4 | 1 | 2.6 | 3 | 3.9 | |

| Employment status | 0.748 | ||||||

| Employed | 34 | 91.9 | 35 | 89.7 | 69 | 90.8 | |

| Temporarily retired | 1 | 2.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.3 | |

| Retired | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 5.1 | 2 | 2.6 | |

| Employed without remuneration | 1 | 2.7 | 1 | 2.6 | 2 | 2.6 | |

| Without specification | 1 | 2.7 | 1 | 2.6 | 2 | 2.6 | |

| Living condition | 0.286 | ||||||

| Individual household | 5 | 13.5 | 9 | 23.1 | 14 | 18.4 | |

| Multi-person household | 32 | 86.5 | 30 | 76.9 | 62 | 81.6 | |

| Smoking | 0.720 | ||||||

| No | 35 | 92.1 | 35 | 89.7 | 70 | 90.9 | |

| Yes | 3 | 7.9 | 4 | 10.3 | 7 | 9.1 | |

| Alcohol | 0.417 | ||||||

| No | 36 | 94.7 | 35 | 89.7 | 71 | 92.2 | |

| Yes | 2 | 5.3 | 4 | 10.3 | 6 | 7.8 | |

| PSQ | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p | Mean | SD |

| Total score | 62.11 | 11.30 | 62.74 | 13.19 | 0.822 | 62.42 | 12.22 |

| Worries | 51.23 | 18.61 | 51.97 | 17.58 | 0.859 | 51.60 | 17.98 |

| Demands | 64.03 | 22.49 | 57.78 | 18.88 | 0.191 | 60.87 | 20.84 |

| Joy | 36.67 | 14.52 | 28.03 | 15.83 | 0.015 * | 32.29 | 15.71 |

| Tension | 69.82 | 14.35 | 69.23 | 18.14 | 0.874 | 69.52 | 16.27 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||||

| Tedium-Measure Burnout | 4.19 | 0.54 | 4.33 | 0.54 | 0.266 | 4.26 | 0.54 |

| Psycho-vegetative complaints | 56.74 | 13.86 | 53.72 | 13.12 | 0.330 | 55.21 | 13.48 |

| ISR total scores | 1.13 | 0.51 | 1.07 | 0.42 | 0.560 | 1.10 | 0.47 |

| General mood state severity (VAS) | 58.82 | 15.24 | 53.69 | 15.12 | 0.143 | 56.22 | 15.30 |

| Well-being (WHO-5) | 7.89 | 3.65 | 10.56 | 10.48 | 0.140 | 9.25 | 7.95 |

| Vitality (SF-36) | 35.00 | 15.55 | 37.69 | 15.34 | 0.447 | 36.36 | 15.40 |

| Self-efficacy (SWOP) | 12.21 | 2.73 | 11.41 | 2.45 | 0.180 | 11.81 | 2.61 |

| Optimism (SWOP) | 5.32 | 1.36 | 4.74 | 1.25 | 0.058 | 5.03 | 1.33 |

| Pessimism (SWOP) | 5.00 | 1.19 | 5.00 | 1.19 | 1 | 5.00 | 1.18 |

| Sense of Coherence (SOC) | 54.53 | 9.16 | 54.54 | 9.44 | 0.995 | 54.53 | 9.25 |

| Life satisfaction (FLZ) | 33.34 | 27.37 | 29.97 | 26.70 | 0.587 | 31.64 | 26.91 |

| Intervention Group (n = 38) | Control Group (n = 39) | Between Groups | ANCOVA | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | ΔM0 | Cohen’s d | Mean | SD | ΔM0 | Cohen’s d | Mean Difference ΔM0 [95% CI] | Cohen’s d | Parameter Estimate for Group Factor [95% CI] | |

| PSQ total score ITT | |||||||||||

| M0 | 62.11 | 11.30 | 62.74 | 13.19 | −0.63 [−6.21; 4.95] | ||||||

| M3 | 44.71 | 14.95 | −17.39 | −1.13 *** | 59.06 | 15.88 | −3.68 | −0.33. | −13.72 [−20.14; −7.30] | −1.02 *** | −14.70 [−20.94; −8.45] |

| M6 | 36.86 | 15.46 | −25.25 | −1.55 *** | 57.32 | 15.60 | −5.41 | −0.45 ** | −19.84 [−26.47; −13.20] | −1.38 *** | −21.02 [−27.34; −14.70] |

| M9 | 36.84 | 15.71 | −25.27 | −1.37 *** | |||||||

| M12 | 33.90 | 14.43 | −28.20 | −1.70 *** | |||||||

| Sensitivity analysis for PSQ total score PP | |||||||||||

| M3 | 44.76 | 15.44 | −17.71 | −1.31 *** | 59.19 | 16.43 | −4.24 | −0.27 * | −13.48 [−19.84; −7.11] | −1.01 *** | −14.20 [−20.54; −7.85] |

| M6 | 37.15 | 16.70 | −24.46 | −1.70 *** | 57.57 | 16.06 | −5.05 | −0.34 * | −19.42 [−26.10; −12.43] | −1.37 *** | −20.51 [−27.48; −13.54] |

| M9 | 36.04 | 17.39 | −25.80 | −1.78 *** | |||||||

| M12 | 33.91 | 15.88 | −28.79 | −2.13 *** | |||||||

| PSQ worries ITT | |||||||||||

| M0 | 51.23 | 18.61 | 51.97 | 17.58 | −0.74 [−8.96; 7.48] | ||||||

| M3 | 34.74 | 14.97 | −16.49 | −0.92 *** | 48.87 | 19.68 | −3.09 | −0.18 | −13.40 [−21.80; −4.99] | −0.76 ** | −14.36 [−21.87; −6.84] |

| M6 | 27.19 | 16.56 | −24.04 | −1.18 *** | 47.78 | 20.45 | −4.19 | −0.24 | −19.85 [−28.85; −10.85] | −1.04 *** | −21.48 [−29.61; −13.36] |

| M9 | 25.75 | 17.49 | −25.47 | −1.24 *** | |||||||

| M12 | 24.30 | 15.53 | −26.93 | −1.38 *** | |||||||

| PSQ demands ITT | |||||||||||

| M0 | 64.04 | 22.49 | 57.78 | 18.88 | 6.26 [−3.16; 15.68] | ||||||

| M3 | 45.79 | 22.04 | −18.25 | −0.87 *** | 56.48 | 23.03 | −1.30 | −0.08 | −16.95 [−26.56; −7.33] | −0.89 *** | −15.96 [−25.19; −6.73] |

| M6 | 42.60 | 23.60 | −21.44 | −1.09 *** | 52.91 | 20.87 | −4.87 | −0.27 | −16.57 [−25.82; −7.31] | −0.88 *** | −15.33 [−24.47; −6.19] |

| M9 | 45.00 | 23.95 | −19.04 | −0.79 *** | |||||||

| M12 | 39.30 | 20.81 | −24.74 | −1.30 *** | |||||||

| PSQ joy ITT | |||||||||||

| M0 | 36.67 | 14.52 | 28.03 | 15.83 | 8.63 [1.73; 15.54] | ||||||

| M3 | 50.79 | 19.46 | 14.12 | 0.78 *** | 35.37 | 17.21 | 7.33 | 0.52 ** | 6.79 [−1.18; 14.76] | 0.42 | 10.16 [2.19; 18.14] |

| M6 | 60.18 | 19.83 | 23.51 | 1.28 *** | 33.90 | 18.91 | 5.86 | 0.37 * | 17.65 [9.07; 26.22] | 1.02 *** | 21.51 [12.58; 30.44] |

| M9 | 61.70 | 20.19 | 25.04 | 1.13 *** | |||||||

| M12 | 62.07 | 20.71 | 25.40 | 1.18 *** | |||||||

| PSQ tension ITT | |||||||||||

| M0 | 69.82 | 14.35 | 69.23 | 18.14 | 0.59 [−6.85; 8.03] | ||||||

| M3 | 49.11 | 17.99 | −20.72 | −0.96 *** | 66.26 | 20.59 | −2.97 | −0.18 | −17.75 [−26.97; −8.52] | −0.91 *** | −18.48 [−26.92; −10.03] |

| M6 | 37.82 | 18.27 | −32.00 | −1.39 *** | 62.51 | 22.64 | −6.72 | −0.41 * | −25.28 [−34.91; −15.66] | −1.26 *** | −25.87 [−35.04; −16.70] |

| M9 | 38.30 | 21.68 | −31.53 | −1.24 *** | |||||||

| M12 | 34.09 | 18.17 | −35.74 | −1.56 *** | |||||||

| ANCOVA Results | Estimate | SE | df | [95% CI] | t | p | Par. n2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITT population | |||||||

| Intercept | 30.37 | 11.29 | 61.81 | [7.81; 52.93] | 2.69 | 0.009 | |

| Group (IHM/CC) | −21.02 | 3.17 | 68.04 | [−27.34; −14.70] | −6.63 | <0.001 | 0.38 |

| PSQ baseline score | −0.35 | 0.13 | 67.74 | [−0.61; −0.10] | −2.73 | 0.008 | 0.10 |

| Gender | −7.16 | 4.34 | 63.44 | [−15.84; 1.52] | −1.65 | 0.104 | 0.04 |

| PP Population | |||||||

| Intercept | 17.73 | 10.37 | 62 | [−2.99; 38.45] | 1.71 | 0.092 | |

| Group (IHM/CC) | −20.51 | 3.49 | 62 | [−27.47; −13.54] | −5.89 | <0.001 | 0.34 |

| PSQ baseline score | −0.28 | 0.14 | 62 | [−0.56; 0.01] | −1.96 | 0.055 | 0.06 |

| Gender | −5.79 | 4.85 | 62 | [−15.48; 3.90] | −1.20 | 0.237 | 0.02 |

| Intervention Group (n = 35) | Control Group (n = 35) | Between Groups | ANCOVA | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | ΔM0 | Cohen’s d | Mean | SD | ΔM0 | Cohen’s d | Mean Difference ΔM0 [95% CI] | Cohen’s d | Parameter Est. for Group [95% CI] | |

| PSQ total score ITT | |||||||||||

| M0 | 57.57 | 16.06 | 62.62 | 13.17 | |||||||

| M3 | 46.54 | 20.72 | −11.03 | −0.80 *** | 58.37 | 15.92 | −4.25 | −0.39 * | −6.78 [−12.42; −1.14] | −0.54 * | −7.64 [−12.94; −2.34] |

| M6 | 38.83 | 22.23 | −18.74 | −0.99 *** | 57.57 | 16.06 | −5.05 | −0.44 * | −13.69 [−21.74; −5.64] | −0.88 ** | −15.23 [−22.36; −8.10] |

| M9 | 45.68 | 21.70 | −11.89 | −0.69 *** | |||||||

| M12 | 35.80 | 18.58 | −21.77 | −1.57 *** | |||||||

| Sensitivity analysis for PSQ total score PP | |||||||||||

| M3 | 46.24 | 20.87 | −11.61 | −0.59 *** | 58.38 | 15.96 | −4.41 | −0.29 * | −6.67 [−12.10; −1.23] | −0.55 * | −7.72 [−12.83; −2.60] |

| M6 | 38.33 | 22.08 | −19.11 | −0.96 *** | 57.57 | 16.06 | −5.05 | −0.34 * | −13.78 [−22.04; −5.51] | −0.89 ** | −15.56 [−22.75; −8.36] |

| M9 | 44.81 | 23.35 | −11.16 | −0.52 ** | |||||||

| M12 | 34.47 | 18.07 | −21.60 | −1.22 *** | |||||||

| Intervention Group (n = 38) | Control Group (n = 39) | Between Groups | ANCOVA | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | ΔM0 | Cohen’s d | Mean | SD | ΔM0 | Cohen’s d | Mean Difference ΔM0 [95% CI] | Cohen’s d | Parameter Est. for group [95% CI] | |

| Tedium-Measure (Burnout): total score | |||||||||||

| M0 | 4.19 | 0.54 | 4.33 | 0.54 | |||||||

| M3 | 3.42 | 0.75 | −0.77 | −1.15 *** | 4.19 | 0.71 | −0.14 | −0.25 | −0.63 [−0.92; −0.35] | −1.03 *** | −0.69 [−0.98, −0.40] |

| M6 | 2.99 | 0.71 | −1.20 | −1.50 *** | 4.06 | 0.70 | −0.27 | −0.46 ** | −0.94 [−1.26; −0.61] | −1.34 *** | −1.06 [−1.36, −0.75] |

| M9 | 2.75 | 0.68 | −1.45 | −1.71 *** | |||||||

| M12 | 2.74 | 0.73 | −1.45 | −1.77 *** | |||||||

| Psycho-vegetative complaints total score | |||||||||||

| M0 | 56.74 | 13.86 | 53.72 | 13.12 | |||||||

| M3 | 41.92 | 14.01 | −14.82 | −1.03 *** | 51.98 | 14.86 | −1.74 | −0.19 | −13.08 [−18.81; −7.35] | −1.08 *** | −13.03 [−18.43, −7.63] |

| M6 | 35.58 | 15.43 | −21.15 | −1.24 *** | 50.77 | 15.08 | −2.94 | −0.25 | −18.21 [−25.06; −11.36] | −1.24 *** | −17.99 [−24.34, −11.64] |

| M9 | 34.41 | 14.12 | −22.33 | −1.25 *** | |||||||

| M12 | 31.07 | 14.45 | −25.67 | −1.48 *** | |||||||

| ISR: total score | |||||||||||

| M0 | 1.13 | 0.51 | 1.07 | 0.42 | |||||||

| M3 | 0.87 | 0.47 | −0.26 | −0.66 *** | 1.07 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.27 [−0.44, −0.10] | −0.72 ** | −0.29 [−0.44, −0.14] |

| M6 | 0.72 | 0.43 | −0.41 | −0.85 *** | 0.98 | 0.37 | −0.09 | −0.25 | −0.32 [−0.52, −0.12] | −0.76 ** | −0.33 [−0.48, −0.17] |

| M9 | 0.66 | 0.41 | −0.47 | −0.99 *** | |||||||

| M12 | 0.53 | 0.36 | −0.61 | −1.21 *** | |||||||

| WHO well-being index | |||||||||||

| M0 | 7.89 | 3.65 | 9.26 | 4.73 | |||||||

| M3 | 12.86 | 5.28 | 4.97 | 0.95 *** | 9.96 | 5.34 | 0.71 | 0.16 | 4.26 [1.94, 6.58] | 0.86 *** | 3.85 [1.59, 6.11] |

| M6 | 15.03 | 4.28 | 7.14 | 1.42 *** | 9.67 | 5.18 | 0.41 | 0.08 | 6.73 [4.31, 9.15] | 1.28 *** | 6.05 [3.88, 8.22] |

| M9 | 14.61 | 5.92 | 6.71 | 1.13 *** | |||||||

| M12 | 15.82 | 4.25 | 7.92 | 1.65 *** | |||||||

| Vitality | |||||||||||

| M0 | 35.00 | 15.55 | 37.69 | 15.34 | |||||||

| M3 | 52.08 | 20.54 | 17.08 | 0.82 *** | 40.31 | 20.59 | 2.62 | 0.17 | 14.46 [5.34, 23.59] | 0.79 ** | 14.79 [5.96, 23.62] |

| M6 | 60.58 | 19.37 | 25.58 | 1.06 *** | 40.17 | 19.06 | 2.47 | 0.15 | 23.10 [4.88, 13.35] | 1.11 *** | 22.49 [13.66, 31.32] |

| M9 | 60.05 | 22.37 | 25.05 | 1.03 *** | |||||||

| M12 | 63.55 | 18.44 | 28.55 | 1.17 *** | |||||||

| Self-efficacy (SWOP) | |||||||||||

| M0 | 12.21 | 2.73 | 11.41 | 2.45 | |||||||

| M3 | 13.26 | 2.70 | 1.05 | 0.47 ** | 12.12 | 2.33 | 0.71 | 0.37 | 0.34 [−0.73, 1.41] | 0.16 | 0.70 [−0.34, 1.75] |

| M6 | 14.59 | 2.53 | 2.38 | 0.89 *** | 11.83 | 2.28 | 0.42 | 0.19 | 1.96 [0.74, 3.17] | 0.78 ** | 2.49 [1.41, 3.56] |

| M9 | 15.04 | 2.88 | 2.83 | 1.10 *** | |||||||

| M12 | 15.47 | 2.44 | 3.26 | 1.23 *** | |||||||

| Sense of Coherence (SOC): total score | |||||||||||

| M0 | 54.53 | 9.16 | 54.54 | 9.44 | |||||||

| M3 | 60.10 | 11.74 | 5.57 | 0.51 ** | 55.22 | 11.06 | 0.68 | 0.08 | 4.89 [0.25, 9.53] | 0.50 * | 5.36 [0.85, 9.89] |

| M6 | 64.61 | 11.59 | 10.08 | 1.01 *** | 54.76 | 11.18 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 9.87 [5.00, 14.73] | 1.07 *** | 10.04 [5.17, 14.91] |

| M9 | 65.90 | 10.61 | 11.38 | 1.03 *** | |||||||

| M12 | 65.23 | 11.16 | 10.71 | 0.90 *** | |||||||

| Life satisfaction (FLZ): total score | |||||||||||

| M0 | 33.34 | 27.37 | 29.97 | 26.70 | |||||||

| M3 | 42.51 | 25.83 | 9.17 | 0.33. | 40.24 | 26.70 | 10.26 | 0.50 ** | −1.09 [13.32, 11.14] | −0.04 | 1.00 [−9.84, 11.84] |

| M6 | 59.90 | 28.28 | 26.56 | 0.75 *** | 33.13 | 26.40 | 3.16 | 0.16 | 23.40 [9.63, 37.16] | 0.81 ** | 27.53 [15.77, 39.30] |

| M9 | 63.50 | 29.29 | 30.16 | 0.91 *** | |||||||

| M12 | 62.93 | 32.75 | 29.59 | 0.83 *** | |||||||

| General mood state severity (VAS) | |||||||||||

| M0 | 58.82 | 15.24 | 53.69 | 15.12 | |||||||

| M3 | 36.70 | 16.16 | −22.11 | −1.18 *** | 51.33 | 20.87 | −2.37 | −0.11 | −19.75 [−29.29, −10.20] | −0.96 *** | −17.45 [−26.08, −8.81] |

| M6 | 29.88 | 14.92 | −28.93 | −1.45 *** | 57.64 | 17.16 | 3.94 | 0.18 | −32.88 [−42.76, −22.99] | −1.58 *** | −29.71 [−37.74, −21.68] |

| M9 | 30.86 | 18.20 | −27.96 | −1.20 *** | |||||||

| M12 | 28.50 | 15.63 | −30.32 | −1.33 *** | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Melchart, D.; Wühr, E.; Bachmeier, B.; Jötten, L.I. Individual Health Management (IHM) for Stress—A Randomised Controlled Trial (TALENT II Study). Healthcare 2025, 13, 3181. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233181

Melchart D, Wühr E, Bachmeier B, Jötten LI. Individual Health Management (IHM) for Stress—A Randomised Controlled Trial (TALENT II Study). Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3181. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233181

Chicago/Turabian StyleMelchart, Dieter, Erich Wühr, Beatrice Bachmeier, and Lara Isabel Jötten. 2025. "Individual Health Management (IHM) for Stress—A Randomised Controlled Trial (TALENT II Study)" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3181. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233181

APA StyleMelchart, D., Wühr, E., Bachmeier, B., & Jötten, L. I. (2025). Individual Health Management (IHM) for Stress—A Randomised Controlled Trial (TALENT II Study). Healthcare, 13(23), 3181. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233181