Psychometric Validation and Factor Structure of the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire—Short Form in the Romanian Private Healthcare Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Translation Process

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Construct Validity

3.1.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

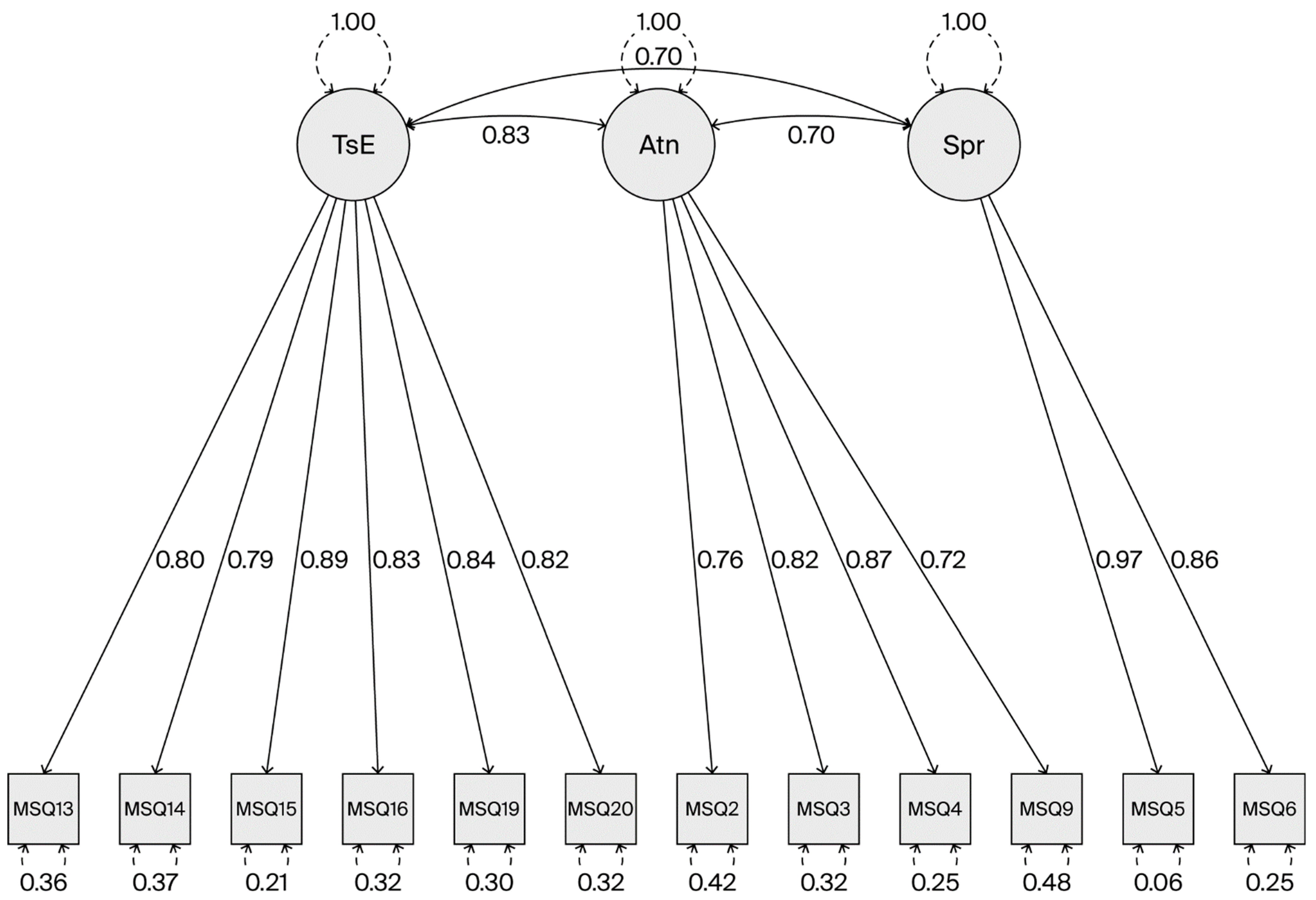

3.1.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.1.3. Internal Consistency

3.1.4. Network Analysis

4. Discussions

4.1. Principal Findings and Comparisons

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Further Works

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MSQ | Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire |

| MSQ-SF | Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire–Short Form |

| JSS | Job Satisfaction Questionnaire |

| eNPS | Employee Net Promoter Score |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| MCAR | Missing Completely at Random |

| KMO | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewins Index |

| NFI | Bentler–Bonett Normed Fit Index |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| HTMT | Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio |

| PNFI | Parsimonious Normed Fit Index |

| RFI | Relative Fit Index |

| IFI | Incremental Fit Index |

| RNI | Relative Noncentrality Index |

| GFI | Goodness-of-Fit Index |

| PDI | Power Distance |

Appendix A

| Item Abbreviation | Question |

|---|---|

| MSQ1 | Posibilitatea de a avea tot timpul ceva de făcut Being able to keep busy all the time |

| MSQ2 | Oportunitatea de a lucra singur, independent. The chance to work alone on the job |

| MSQ3 | Oportunitatea de a face lucruri diferite din când în când. The chance to do different things from time to time |

| MSQ4 | Oportunitatea de a fi recunoscut în comunitate. The chance to be “somebody” in the community |

| MSQ5 | Modul în care șeful meu își tratează angajații. The way my boss handles his/her workers |

| MSQ6 | Competența șefului meu direct în luarea deciziilor. The competence of my supervisor in making decisions |

| MSQ7 | Posibilitatea de a face lucruri care nu contravin principiilor mele morale. Being able to do things that do not go against my conscience |

| MSQ8 | Modul în care locul meu de muncă oferă stabilitate. The way my job provides for steady employment |

| MSQ9 | Oportunitatea de a face lucruri pentru alți oameni. The chance to do things for other people |

| MSQ10 | Oportunitatea de a da indicații altora. The chance to tell people what to do |

| MSQ11 | Oportunitatea de a-mi valorifica abilitățile. The chance to do something that makes use of my abilities |

| MSQ12 | Modul în care politicile instituției sunt puse în practică. The way company policies are put into practice |

| MSQ13 | Salariul în raport cu volumul de muncă. My pay and the amount of work I do |

| MSQ14 | Oportunitățile de promovare în acest loc de muncă. The chances for advancement on this job |

| MSQ15 | Libertatea de a-mi folosi propria judecată. The freedom to use my own judgment |

| MSQ16 | Posibilitatea de a încerca propriile metode pentru îndeplinirea sarcinilor de serviciu. The chance to try my own methods of doing the job |

| MSQ17 | Condițiile de muncă. The working conditions |

| MSQ18 | Modul în care colegii mei se înțeleg între ei. The way my co-workers get along with each other |

| MSQ19 | Aprecierea primită pentru o muncă bine făcută. The praise I get for doing a good job |

| MSQ20 | Sentimentul de împlinire pe care mi-l oferă locul de muncă. The feeling of accomplishment I get from the job |

| MSQ21 (SATGEN) | În general, cât de mulțumit sunteți la acest loc de muncă? Overall, how satisfied are you with this job? |

| Very Satisfied | Foarte mulțumit |

| Satisfied | Mulțumit |

| Neither Satisfied nor Dissatisfied | Nici mulțumit, nici nemulțumit |

| Dissatisfied | Nemulțumit |

| Very Dissatisfied | Foarte nemulțumit |

References

- OECD. Rethinking Health System Performance Assessment: A Renewed Framework; OECD Health Policy Studies: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, K.; van Diepen, C.; Fors, A.; Axelsson, M.; Bertilsson, M.; Hensing, G. Healthcare professionals’ experiences of job satisfaction when providing person-centred care: A systematic review of qualitative studies. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e071178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E. Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Causes, and Consequences; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, D.J.; Dawis, R.V.; England, G.W. Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. Minn. Stud. Vocat. Rehabil. 1967, 22, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.C.; Kendall, L.M.; Hulin, C.L. Job Descriptive Index; APA PsycTests: Washington, DC, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichheld, F.F. The one number you need to grow. Harv. Bus Rev. 2003, 81, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abugre, J.B. Job Satisfaction of Public Sector Employees in Sub-Saharan Africa: Testing the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire in Ghana. Int. J. Public Adm. 2014, 37, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, S.; Adewole, D.A.; Afolabi, R.F. Work Facets Predicting Overall Job Satisfaction among Resident Doctors in Selected Teaching Hospitals in Southern Nigeria: A Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire Survey. J. Occup. Health Epidemiol. 2020, 9, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakatamitou, I.; Lambrinou, E.; Kyriakou, M.; Paikousis, L.; Middleton, N. The Greek versions of the TeamSTEPPS teamwork perceptions questionnaire and Minnesota satisfaction questionnaire “short form”. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, H.; Proença, M.T. Minnesota satisfaction questionnaire: Psychometric properties and validation in a population of portuguese hospital workers. Conferência Investig. Interv. Recur. Hum. 2014, 471, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkowiak, D.; Staszewski, R. Nurses’ job satisfaction–the factor structure of the Minnesota satisfaction questionnaire. J. Health Study Med. 2019, 2, 77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Fang, T.; Liu, F.; Pang, L.; Wen, Y.; Chen, S.; Gu, X. Career Adaptability Research: A Literature Review with Scientific Knowledge Mapping in Web of Science. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, C.M.; Nguyen, C.H.; Le, K.N.D.; Tran, P.T.N.; Nguyen, P.M. Job Satisfaction within the Grassroots Healthcare System in Vietnam’s Key Industrial Region-Binh Duong Province: Validating the Vietnamese Version of the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire Scale. Healthcare 2024, 12, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhippayom, J.P.; Trevittaya, P.; Cheng, A.S.K. Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Validity, and Reliability of the Patient-Rated Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire for Thai Patients. Occup. Ther. Int. 2018, 2018, 8319875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndt, A.E. Sampling Methods. J. Hum. Lact. 2020, 36, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, M.; AL-Muaalemi, M.A. Sampling Techniques for Quantitative Research. In Principles of Social Research Methodology; Islam, M.R., Khan, N.A., Baikady, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfeld, R.R. Does revising the intrinsic and extrinsic subscales of the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire short form make a difference? Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2000, 60, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, B.; Schwab, D.P. Convergent and Discriminant Validities of Corresponding Job Descriptive Index and Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire Scales. J. Appl. Psychol. 1975, 60, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Artino, A.R., Jr. Analyzing and interpreting data from likert-type scales. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2013, 5, 541–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bledsoe, J.C.; Brown, S.E. Factor Structure of the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1977, 45, 301–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, N.A.; Hammond, G.D. A meta-analytic examination of the construct validity of the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire Job Satisfaction Subscale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 73, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancer, M.; George, R.T. Factor structure of the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire short form for restaurant employees. Psychol. Rep. 2004, 94, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Saane, N.; Sluiter, J.K.; Verbeek, J.H.A.M.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W. Reliability and validity of instruments measuring job satisfaction—A systematic review. Occup. Med. 2003, 53, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dikopoulou, Z. Network Analysis, Accuracy and Stability of the Job-Satisfaction Structures. In Modeling and Simulating Complex Business Perceptions: Using Graphical Models and Fuzzy Cognitive Maps; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 85–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomer, B.; Yuan, K.H. A Realistic Evaluation of Methods for Handling Missing Data When There is a Mixture of MCAR, MAR, and MNAR Mechanisms in the Same Dataset. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2023, 58, 988–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holgado-Tello, F.P.; Chacón-Moscoso, S.; Barbero-García, I.; Vila-Abad, E. Polychoric versus Pearson correlations in exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of ordinal variables. Qual. Quant. 2010, 44, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, U. Maximum Likelihood Estimation of the Polychoric Correlation Coefficient. Psychometrika 1979, 44, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Market Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. Validity and Reliability of the Research Instrument; How to Test the Validation of a Questionnaire/Survey in a Research. SSRN Electron. J. 2016, 5, 3205040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, R.O.; Hancock, G.R. Factor Analysis and Latent Structure Analysis: Confirmatory Factor Analysis. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Wright, J.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 686–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif-Nia, H.; She, L.; Osborne, J.; Gorgulu, O.; Fomani, F.K.; Goudarzian, A.H. Statistical concerns, invalid construct validity, and future recommendations. Nurs. Pract. Tod 2024, 11, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamson, K.A.; Prion, S. Reliability: Measuring Internal Consistency Using Cronbach’s α. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2013, 9, E179–E180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaske, J.J.; Beaman, J.; Sponarski, C.C. Rethinking Internal Consistency in Cronbach’s Alpha. Leisure Sci. 2017, 39, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, G.; Perugini, M. The network of conscientiousness. J. Res. Pers. 2016, 65, 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Cramer, A.O.J.; Waldorp, L.J.; Schmittmann, V.D.; Borsboom, D. qgraph: Network Visualizations of Relationships in Psychometric Data. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Borsboom, D.; Fried, E.I. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behav. Res. Methods 2018, 50, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitendach, J.H.; Rothmann, S. The Validation of the Minnesota Job Satisfaction Questionnaire in Selected Organisations in South Africa. S. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marijani, R.; Yohana, M. The validation of the Minnesota job satisfaction questionnaire (MSQ) in Tanzania: A case of Tanzania public service college. Int. J. Afr. Asian Stud. 2016, 23, 162–172. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Enezi, N.; Chowdhury, R.I.; Shah, M.A.; Al-Otabi, M. Job satisfaction of nurses with multicultural backgrounds: A questionnaire survey in Kuwait. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2009, 22, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai Pranav, K.; Deepika, S. Relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment of employees working in a public undertaking: A pilot study. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2022, 7, 214–226. [Google Scholar]

- Ueltschy, L.C.; Laroche, M.; Tamilia, R.D.; Yannopoulos, P. Cross-cultural invariance of measures of satisfaction and service quality. J. Bus Res. 2004, 57, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihut, I.; Lungescu, D. Cultural Dimensions in the Romanian Management. Manag. Mark. 2006, 1, 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.; Islam, M.T. Validating the MSQ of Job Satisfaction in Bangladesh: A Study on the Context of Public Commercial Banks. J. Bus. Stud. 2019, 40, 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Vaduva, S.; Igor, P.; Lîsîi, A. The Particularities of Romanian Management. In Romanian Management Theory and Practice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, A.; Dan, H.; Coroian, A.; Gavris, O. The impact of organizational culture on the competitiveness of organizations in the current context. In Proceedings of the 33rd IBIMA Conference, Granada, Spain, 10–11 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pana, B.C.; Ciufu, N.; Ciufu, C.; Furtunescu, F.L.; Turcu-Stiolica, A.; Mazilu, L. Digital technology for health shows disparities in cancer prevention between digital health technology users and the general population in Romania. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1171699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, L.; Sharif, S.P.; Nia, H.S. Psychometric Evaluation of the Chinese Version of the Modified Online Compulsive Buying Scale among Chinese Young Consumers. J. Asia-Pac. Bus. 2021, 22, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, H.; Goyal, S. Validation of Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire: A Study of Front-Line Retail Employees. SSRN Electron. J. 2016, 2864211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; He, B.S.; Gong, S.C.; Sheng, M.H.; Ruan, X.W. Network analysis of occupational stress and job satisfaction among radiologists. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1411688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokurugu, M.A.; Aninanya, G.A.; Alhassan, M.; Dowou, R.K.; Daliri, D.B. Factors influencing the level of patients’ satisfaction with mental healthcare delivery in Tamale Metropolis: A multicentre cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, G.; Epskamp, S.; Borsboom, D.; Perugini, M.; Mottus, R.; Waldorp, L.J.; Cramer, A.O.J. State of the aRt personality research: A tutorial on network analysis of personality data in R. J. Res. Pers. 2015, 54, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, A.; Bond, S. Hospital nurses’ job satisfaction, individual and organizational characteristics. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 32, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, C.; Millner, A.J.; Forgeard, M.J.C.; Fried, E.I.; Hsu, K.J.; Treadway, M.T.; Leonard, C.V.; Kertz, S.J.; Bjögvinsson, T. Network analysis of depression and anxiety symptom relationships in a psychiatric sample. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 3359–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.Q.; Zhang, X.Q.; Wang, P. Interconnected Stressors and Well-being in Healthcare Professionals. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2025, 20, 459–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.Y.; Ma, X.Q. Network analysis of the relationship between error orientation, self-efficacy, and innovative behavior in nurses. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Weiss (Original) [4] | Walkowiak et al., 2019 [11] | Martins, H., 2012 [10] | Huynh et al., 2024 [13] | Lakatamitou et al., 2020 [9] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | USA | Poland | Portugal | Vietnam | Cyprus |

| MSQ1 | Intrinsic | Intrinsic | *** | Specificity | *** |

| MSQ2 | Intrinsic | Intrinsic | Supervisor/Empowerment | Specificity | Supervisor/Autonomy |

| MSQ3 | Intrinsic | Intrinsic | Task Enrichment | Specificity | Supervisor/Autonomy |

| MSQ4 | Intrinsic | Intrinsic | Supervisor/Empowerment | Autonomy | Supervisor/Autonomy |

| MSQ5 | Extrinsic | Extrinsic | Supervisor/Empowerment | Autonomy | *** |

| MSQ6 | Extrinsic | Extrinsic | Supervisor/Empowerment | *** | *** |

| MSQ7 | Intrinsic | Intrinsic | *** | *** | Supervisor/Autonomy |

| MSQ8 | Intrinsic | (Intrinsic) | *** | *** | Supervisor/Autonomy |

| MSQ9 | Intrinsic | Intrinsic | *** | Autonomy | Supervisor/Autonomy |

| MSQ10 | Intrinsic | Intrinsic | Task Enrichment | Autonomy | Supervisor/Autonomy |

| MSQ11 | Intrinsic | Intrinsic | Task Enrichment | Autonomy | Supervisor/Autonomy |

| MSQ12 | Extrinsic | Extrinsic | *** | *** | *** |

| MSQ13 | Extrinsic | Extrinsic | *** | *** | Task Enrichment |

| MSQ14 | Extrinsic | Intrinsic | *** | Obligation | Task Enrichment |

| MSQ15 | Intrinsic | Intrinsic/Extrinsic | Task Enrichment | Obligation | Task Enrichment |

| MSQ16 | Intrinsic | Intrinsic | Task Enrichment | Obligation | Task Enrichment |

| MSQ17 | General | Extrinsic | *** | Obligation | Task Enrichment |

| MSQ18 | General | (Extrinsic) | *** | Autonomy | *** |

| MSQ19 | Extrinsic | Extrinsic | Task Enrichment | *** | Task Enrichment |

| MSQ20 | Intrinsic | Intrinsic | *** | Autonomy | Task Enrichment |

| Number Items Discarded | 0 | 0 | 10 | 6 | 5 |

| 95% CI For Percentage | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

| Gender | Male | 362 | 83.21% | 79.74% | 86.70% |

| Female | 58 | 13.33% | 10.12% | 16.55% | |

| No Answer | 15 | 3.44% | 1.71% | 5.18% | |

| Age | 30 Years Old and Younger | 94 | 21.60% | 17.67% | 25.53% |

| 31 to 40 Years Old | 87 | 20.00% | 16.21% | 23.79% | |

| 41 to 50 Years Old | 87 | 20.00% | 16.21% | 23.79% | |

| 51 Years Old and Above | 100 | 22.98% | 18.94% | 27.04% | |

| No Answer | 67 | 15.40% | 12.03% | 18.77% | |

| Mean ± Standard Deviation | 40.81 ± 11.87 | ||||

| Median | 41 | ||||

| Youngest Age | 19 | ||||

| Oldest Age | 68 | ||||

| 25th Percentile | 30 | ||||

| 75th Percentile | 51 | ||||

| Education Level | Primary School | 1 | 0.23% | 0.00% | 0.63% |

| Middle School | 10 | 2.29% | 1.30% | 0.33% | |

| College | 110 | 25.29% | 21.28% | 29.30% | |

| Tertiary Education | 294 | 67.58% | 63.18% | 72.00% | |

| No Answer | 20 | 4.60% | 3.26% | 5.94% | |

| Leading Role | Yes | 26 | 5.97% | 4.45% | 7.51% |

| No | 400 | 91.95% | 89.50% | 94.40% | |

| No Answer | 9 | 2.06% | 1.13% | 3.01% | |

| Employment Status | Full-Time | 369 | 84.82% | 81.47% | 88.19% |

| Part-Time | 48 | 11.03% | 8.05% | 14.01% | |

| No Answer | 18 | 4.13% | 2.87% | 5.41% | |

| Time Since Initial Employment in The Surveyed Institution [Months] | Employed for Less Than 3 Years | 254 | 58.39% | 53.72% | 63.06% |

| Employed for 3–5 Years | 63 | 14.48% | 11.20% | 17.76% | |

| Employed for Over 5 Years | 99 | 22.75% | 18.72% | 26.80% | |

| No Answer | 19 | 4.36% | 3.06% | 5.68% | |

| Mean ± Standard Deviation [Months] | 42.74 ± 38.53 | ||||

| Median [Months] | 31 | ||||

| Newest Employed in Institution [Months] | 1 | ||||

| Oldest Employed in Institution [Months] | 168 | ||||

| 25th Percentile | 12 | ||||

| 75th Percentile | 60 | ||||

| Time Since Employment in The Workforce [Months] | Mean ± Standard Deviation [Months] | 85.78 ± 101.95 | |||

| Median [Months] | 44 | ||||

| Newest in Workforce [Months] | 1 | ||||

| Oldest in Workforce [Months] | 502 | ||||

| 25th Percentile | 19 | ||||

| 75th Percentile | 111 | ||||

| No Answer | 22 | 5.32% | |||

| Activity Domain | Daycare Fields | 136 | 31.26% | 26.85% | 35.67% |

| Surgical Fields | 91 | 20.92% | 17.05% | 24.79% | |

| Clinical Fields | 86 | 19.77% | 16.02% | 23.52% | |

| Customer Service | 76 | 17.47% | 13.92% | 21.02% | |

| Technical and Administrative Fields | 41 | 9.42% | 6.65% | 12.21% | |

| No Answer | 5 | 1.14% | 0.39% | 1.91% | |

| Professional Background | Healthcare Professional | 296 | 68.04% | 63.67% | 72.43% |

| Administration and Economics | 43 | 9.88% | 7.04% | 12.74% | |

| Technical | 27 | 6.20% | 4.64% | 7.78% | |

| Services | 20 | 4.59% | 3.26% | 5.94% | |

| Military | 3 | 0.69% | 0.16% | 1.22% | |

| Undergraduate | 17 | 3.90% | 2.67% | 5.15% | |

| No Answer | 29 | 6.66% | 5.04% | 8.30% | |

| Current Job Title Category | Doctors and Pharmacists | 44 | 10.11% | 7.23% | 12.99% |

| Nurses | 161 | 37.01% | 32.37% | 41.65% | |

| Nursing Aides | 80 | 18.39% | 14.74% | 22.04% | |

| Support Staff | 86 | 19.77% | 16.02% | 23.52% | |

| Technical Support | 23 | 5.28% | 3.86% | 6.72% | |

| Administrative Staff | 26 | 5.97% | 4.45% | 7.51% | |

| No Answer | 15 | 3.44% | 2.30% | 4.60% | |

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Uniqueness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSQ13 | 0.864 | 0.336 | ||

| MSQ19 | 0.847 | 0.292 | ||

| MSQ15 | 0.822 | 0.233 | ||

| MSQ16 | 0.806 | 0.324 | ||

| MSQ20 | 0.735 | 0.328 | ||

| MSQ14 | 0.697 | 0.376 | ||

| MSQ3 | 0.952 | 0.209 | ||

| MSQ9 | 0.631 | 0.485 | ||

| MSQ4 | 0.605 | 0.312 | ||

| MSQ2 | 0.602 | 0.443 | ||

| MSQ6 | 1.02 | 0.005 | ||

| MSQ5 | 0.695 | 0.233 | ||

| Percentage of variances before rotation | 59.3% | 6.5% | 4.4% | |

| Percentage of variances after rotation | 35.9% | 19.8% | 14.5% | |

| Eigenvalues | 7.41 | 0.929 | 0.835 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pana, B.C.; Maerean, A.; Chirila, S.I.; Radu, C.P.; Mincă, D.G.; Ciufu, V.; Mociu, A.; Ciufu, N. Psychometric Validation and Factor Structure of the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire—Short Form in the Romanian Private Healthcare Context. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3132. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233132

Pana BC, Maerean A, Chirila SI, Radu CP, Mincă DG, Ciufu V, Mociu A, Ciufu N. Psychometric Validation and Factor Structure of the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire—Short Form in the Romanian Private Healthcare Context. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3132. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233132

Chicago/Turabian StylePana, Bogdan C., Alin Maerean, Sergiu Ioachim Chirila, Ciprian Paul Radu, Dana Galieta Mincă, Vlad Ciufu, Adrian Mociu, and Nicolae Ciufu. 2025. "Psychometric Validation and Factor Structure of the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire—Short Form in the Romanian Private Healthcare Context" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3132. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233132

APA StylePana, B. C., Maerean, A., Chirila, S. I., Radu, C. P., Mincă, D. G., Ciufu, V., Mociu, A., & Ciufu, N. (2025). Psychometric Validation and Factor Structure of the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire—Short Form in the Romanian Private Healthcare Context. Healthcare, 13(23), 3132. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233132