Abstract

Background: Tobacco use remains a leading preventable cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States, with persistent disparities in cessation outcomes across socioeconomic and racial groups. While numerous interventions exist, their effectiveness is shaped by complex interrelated factors at individual, social, and healthcare system levels. Identifying and modeling these causal pathways is essential to inform equitable intervention design. Methods: This study applied the Evidence Synthesis for Constructing Directed Acyclic Graphs (ESC-DAG) protocol to integrate empirical findings from 35 quantitative studies examining barriers and facilitators of tobacco cessation intervention uptake in the United States. Using the Andersen and Aday Health Services Research Model as a guiding framework, we extracted, harmonized, and synthesized significant causal relationships into a unified DAG, distinguishing exposures, outcomes, mediators, and confounders. Results: The integrated DAG revealed that structural factors such as socioeconomic disadvantage, digital inequities, rurality, and cultural barriers exerted substantial influence on cessation outcomes. These upstream determinants operated through mediators including motivation, treatment engagement, and access barriers, while healthcare system factors such as provider engagement and proactive outreach emerged as consistent facilitators. Digital access and culturally tailored interventions were identified as underexplored yet potentially high-impact pathways. Discussion: The ESC-DAG methodology provided a structured approach to visualize and synthesize causal mechanisms beyond traditional review synthesis, highlighting points of intervention at both policy and practice levels. The findings underscore the importance of multi-level strategies, including financial support, digital equity initiatives, provider outreach, and culturally tailored cessation services. Conclusions: By applying ESC-DAG methodology, this study contributes a novel causal framework for understanding disparities in tobacco cessation intervention uptake. The resulting DAG can inform future statistical modeling, simulation studies, and equity-focused program design, supporting more effective public health strategies to reduce smoking prevalence and associated inequities.

1. Introduction

Smoking is one of the leading preventable causes of premature death and health inequities in the United States. According to a study conducted in the U.S. from 2014 to 2019 using U.S. population data, a persistent sociodemographic inequality was identified. Although a similar or higher quit interest exists among non-White and lower socioeconomic status groups, significantly lower sustained cessation rates, i.e., only about 7.5% were observed. The tobacco cessation treatment uptake remained low, i.e., 34% and the disparities in treatment receipt did not improve significantly [1]. The NHIS data examination reported similar underlying trends in disparities in receiving professional cessation advice. Those who are older adults, reside in urban areas, have access to primary care, and are diagnosed with COPD were highly likely to receive tobacco cessation treatment assistance, disproportionately affecting rural, younger, uninsured, and racial minority smokers [2,3].

As per a recent CDC MMWR report, about 50% of adult smokers among 28.8 million U.S. adult smokers tried to quit, but only about 10% succeeded, and less than 40% utilized tobacco cessation interventions, i.e., medical or non-medical interventions [4]. Lower access to tobacco cessation interventions and lower sustained quitting are associated with lower socio-economic status and rural residence. Although the cessation intervention exists, access to pharmacotherapy, counselling, or other types of cessation interventions remains limited due to unaligned care coordination, cost, or lower healthcare engagement [2,3,5]. Prior work has identified key barriers and facilitators of cessation intervention utilization in the United States at both the population and healthcare system levels. The key barriers identified across diverse cessation intervention types are digital inequities for digital interventions, socioeconomic disadvantage, and low motivation at the population level. At the healthcare system level, barriers to care access and inadequate healthcare provider engagement have been identified as further system-level barriers in effective tobacco cessation intervention utilization in the U.S., while the key facilitators identified are financial incentives, culturally tailored interventions, and digital engagement strategies [6].

The effectiveness of treatment interventions outside a strict clinical trial environment is affected by several confounding barriers and facilitating factors [7]. It is crucial to identify such factors to develop a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG), a visual representation of complex relationships between key factors affecting the exposure and outcome variables relationship in any observational data study, as it informs the statistical modeling for causal inferences [6,7,8]. A conventional statistical model due to parametric assumptions might not capture the comprehensive causal relationship of a study context; however, a DAG can graphically depict the complex causal relationship between a key exposure and outcome factors. According to PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Google searches, there exists no scientific literature that develops evidence-based DAG on factors affecting tobacco cessation intervention utilization in the United States. As established, it is vital to build such DAGs to identify causal relationships that affect the tobacco cessation intervention utilization to improve the health inequities and smoking prevalence rate in the United States. Although evidence-based cessation intervention exists, there is a need to identify measurable factors that affect the causal relationship between socioeconomic factors and cessation or quit outcomes in the presence of key confounders. Hence, this study builds upon a prior systematic review to develop an evidence synthesis DAG [6].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Evidence Base

This study utilized the Evidence Synthesis for Constructing Directed Acyclic Graphs (ESC-DAG) protocol to identify the causal factors affecting tobacco cessation intervention uptake in the United States. In observational research, the ESC-DAG methodology helps to integrate causal relationships from existing empirical evidence [9].

A total of 35 studies were identified in the prior extension of this work, a systematic review [6] about barriers and facilitators to tobacco cessation interventions at the population and healthcare system levels. The study included randomized control trials, quasi-experimental, and observational quantitative studies that examined determinants of smoking cessation intervention uptake and treatment disparities at both the population and healthcare system level.

Although ESC-DAG methodology typically integrates multiple evidence sources, this study used a prior systematic review that synthesized 35 quantitative studies examining barriers and facilitators of tobacco cessation intervention uptake in the United States. Given the methodological rigor, comprehensive scope, and quality appraisal within that review, it served as a consolidated and sufficient evidence base for DAG construction consistent with established ESC-DAG applications.

2.2. ESC-DAG Protocol Application

The mapping stage included edge identification and coding in DAGitty software (v 3.1) [10]. Each study included was reviewed to extract empirically supported causal relationships/arrows (interchangeably used with terminology edges) between exposure and outcome variables. Edges that were statistically significant between exposure and outcome variables and coded within the original study context were extracted verbatim. The direct and indirect pathways were established without any directionality rules implied to preserve the original study context.

The translation stage included thematic grouping and categorization by imposing ESC-DAG protocol directionality rules. The conceptual framework used to determine the temporality and directionality of constructs was frequently the Andersen and Aday Health Services Research framework [11]. Overlapping constructs, such as digital access and digital inequities, were combined into a single standardized category. The bidirectionality was assessed, and constructs were aligned with theoretical determinants from the conceptual framework.

The integration stage involved synthesis into a final compiled ESC-DAG. The harmonized constructs and their edges were synthesized into a single DAG that included confounders, mediators, and potentially other effect modifiers. Two reviewers (N.P. and S.S.) independently conducted edge extraction from each included study, identifying statistically supported directional relationships (edges) between constructs. The third reviewer (J.I.) synthesized the independent extraction files and conducted a consensus reconciliation. All reviewers jointly applied thematic grouping and temporal alignment following the Andersen and Aday Health Services Research Model. N.P. implemented the final harmonized Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) using DAGitty software, and all three reviewers validated node placement and directionality through iterative review.

2.3. Conceptual Framework and Quality Assurance

The Andersen and Aday Health Services Research Model was utilized as an organizing framework to contextualize constructs across predisposing, enabling, and need-based factors. The protocol recognized the need for a conceptual framework to inform its translation stage, ensuring that the DAG represented statistical associations aligned with established theory on healthcare access and utilization.

3. Results

3.1. Mapping Stage Findings

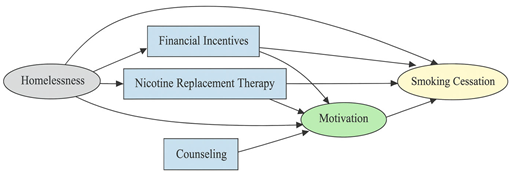

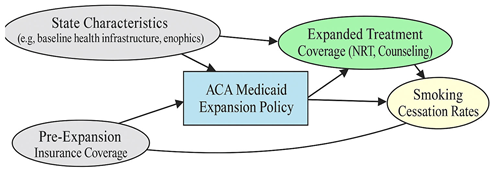

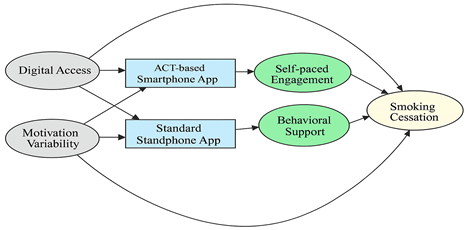

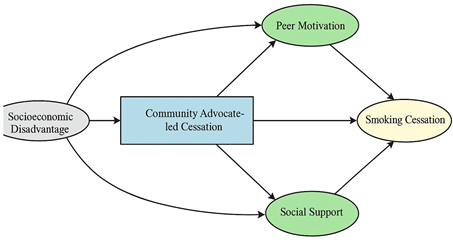

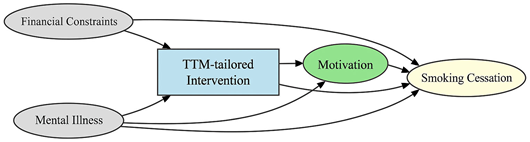

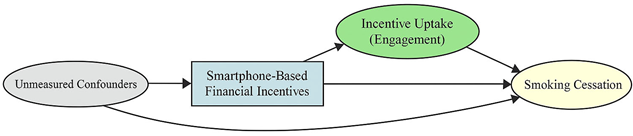

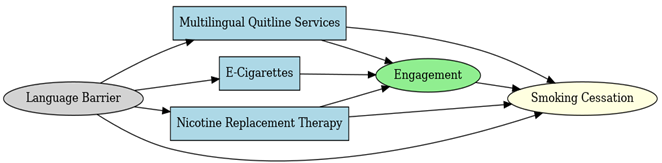

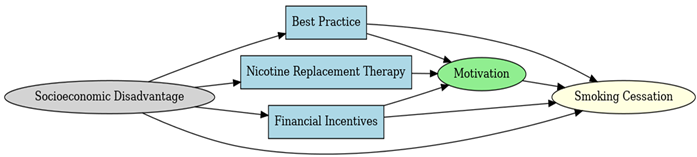

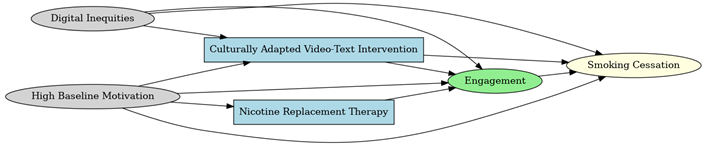

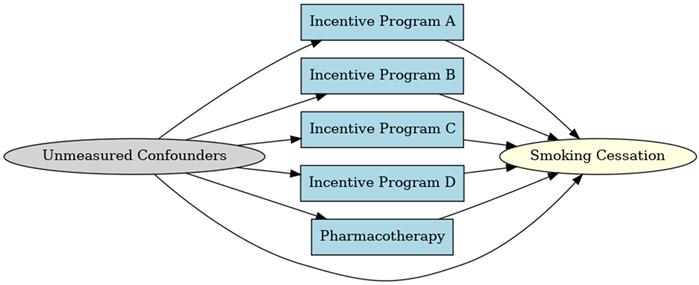

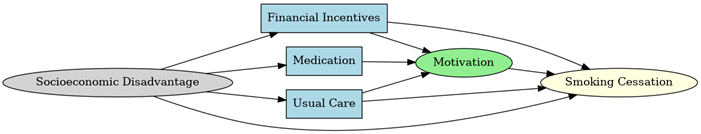

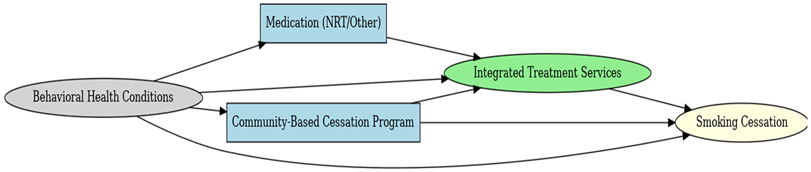

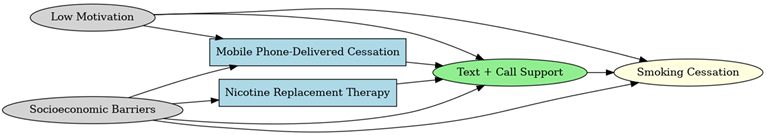

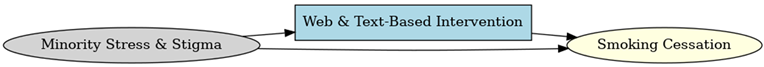

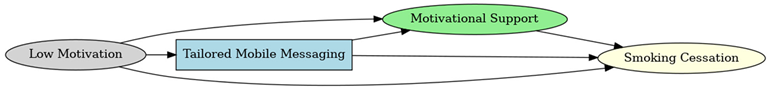

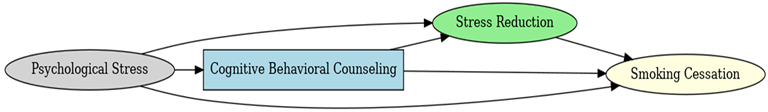

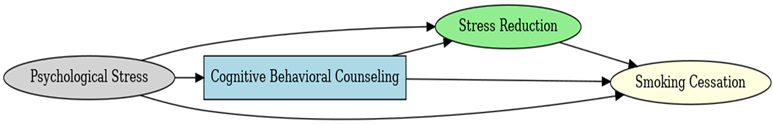

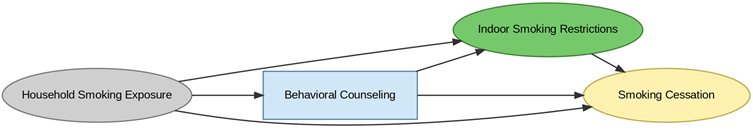

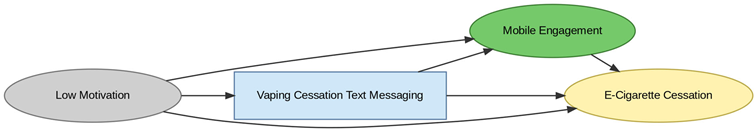

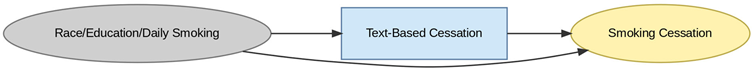

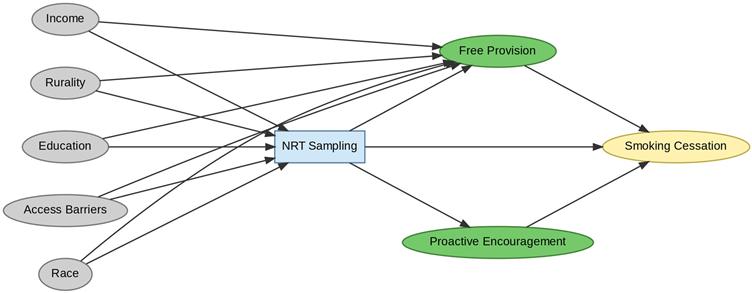

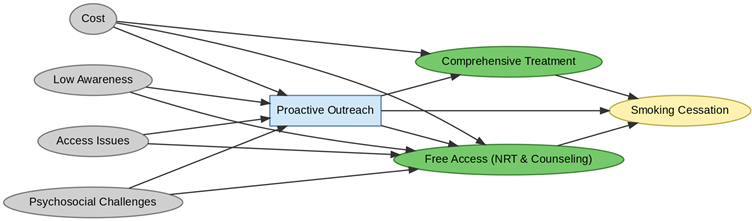

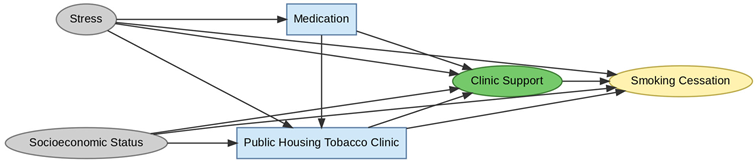

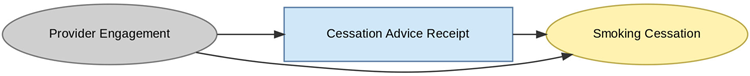

A total of 35 included studies identified a wide range of causal pathways that linked individual, social, and structural factors to smoking cessation outcomes (Table 1). Each study contributed multiple causal pathways, i.e., edges establishing several potential pathways. Frequently mapped factors included socioeconomic disadvantage, digital access and literacy, motivation to quit, and healthcare system barriers, i.e., provider engagement and treatment availability (Table 2). Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT), financial incentives, and mobile-based supports were recurrent intervention-specific nodes. As depicted in Table 1, the yellow nodes represent outcome variables, the blue nodes represent exposure variables, the green nodes represent mediators, and the grey nodes represent confounders, as identified across each included study.

Table 1.

Mapping stage, individual study implied DAGs.

Table 2.

Most frequently and consistently identified barriers and facilitators.

Across the 35 included studies, socioeconomic disadvantage was the most frequently identified barrier (reported in 54% of studies), followed by digital inequities or low digital access (43%), low motivation or readiness to quit (37%), and healthcare access barriers (34%). The most frequently reported facilitators were provider engagement or proactive outreach (49%), financial incentives (40%), digital engagement supports (34%), and culturally tailored interventions (29%). These constructs were consistently represented across RCTs, quasi-experimental, and observational studies, indicating their robustness within the synthesized evidence base.

3.2. Translation Stage and Integration of Extracted DAGs

Following the extraction of individual Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs), a structured translation procedure was implemented to harmonize constructs and establish temporal consistency across studies (Table A1 and Table A2). This process comprised three sequential steps:

3.2.1. Semantic Aggregation

Extracted nodes and edges, i.e., arrows between the nodes (hereafter referred to as edges or causal pathways), were systematically reviewed to identify and reconcile conceptual overlaps. Constructs with equivalent or closely related meanings (e.g., “technology literacy barriers” and “digital access challenges”) were merged into unified categories such as “Digital Access Barriers” or “quitting/vaping/smoking/cessation”. Similarly, outcome constructs, including quit attempt, abstinence, and relapse prevention, were standardized under the category Smoking Cessation. This ensured terminological coherence and reduced redundancy across datasets.

3.2.2. Temporal Re-Alignment

Constructs were organized according to their logical order of influence into upstream determinants, interventions, mechanisms, behaviors, and outcomes. Temporal sequencing was inferred using established causal reasoning and a health behavior framework, including Andersen and Aday’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use. For example, distress consistently preceded intervention access and was thus retained as an upstream determinant rather than reclassified as a mechanism.

3.2.3. Directional Mapping and Validity Assessment

Causal edges were redrawn only when directionality was explicitly supported by primary data or demonstrated consistency across multiple sources. Recourse theory and temporal precedence informed the polarity of edges, thereby avoiding ambiguous or circular paths. Constructs with uncertain directionality were excluded. Face validity of the integrated map was assessed iteratively through expert consensus (n = 3) and triangulated with an established conceptual model.

No single study design was privileged. Instead, causal edges were extracted based on statistical support and mapped uniformly across RCTs, quasi-experimental, and observational studies. Edge direction and placement within the DAG were confirmed using cross-study consistency, temporal precedence, and theoretical plausibility.

3.3. Integrated DAG

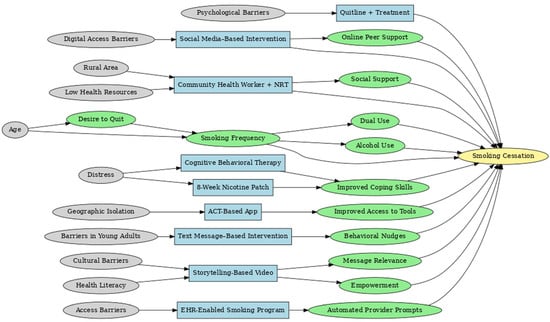

The final Integrated Directed Acyclic Graph (iDAG) presents a comprehensive systems-level representation of the causal architecture underpinning smoking cessation interventions (Figure 1). By synthesizing 35 individual DAGs into a single unified framework, the iDAG illustrates the multilevel and interdependent processes that characterize tobacco cessation through the lens of Andersen and Aday’s Health Services Research conceptual model framework. It delineates how structural inequities cascade through access barriers, intervention modalities, psychological mechanisms, and behavioral mediators to shape cessation outcomes ultimately.

Figure 1.

Integrated DAG Establishing Causal Pathways from Exposure to Outcome Nodes.

3.3.1. Structural: Upstream Determinants

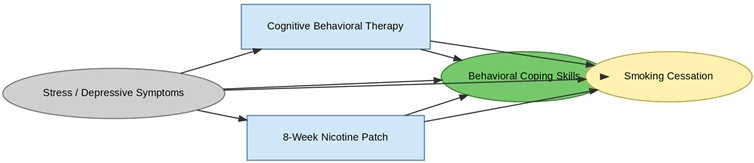

The leftmost domain of the IDAG comprises upstream structural determinants, encompassing demographic and contextual factors such as psychological distress, age, digital access limitations, rural residence, health literacy, and psychosocial barriers. Although these constructs are largely non-manipulable, they are foundational in conditioning access to interventions and moderating treatment effectiveness. For example, psychological distress initiates two distinct causal trajectories: one leading toward Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and another toward Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) sampling, both mediated by improvements in coping capacity.

3.3.2. Intervention: Modality-Specific Pathways

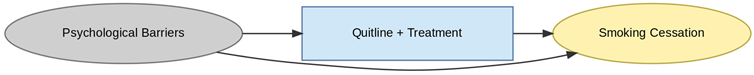

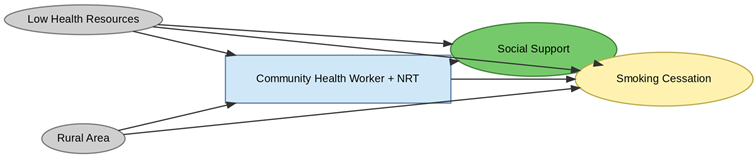

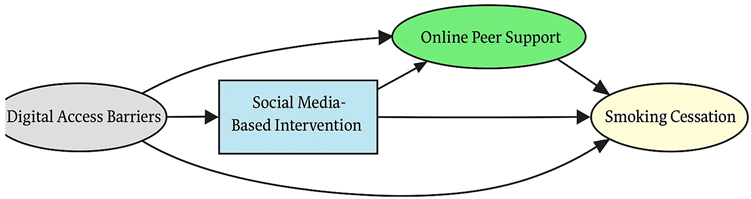

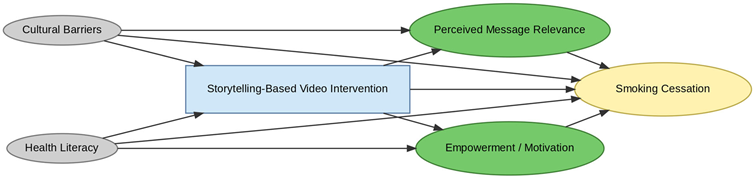

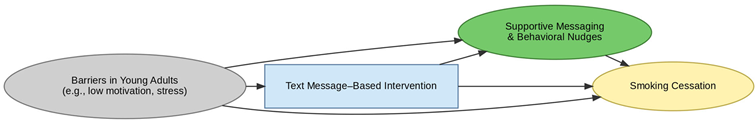

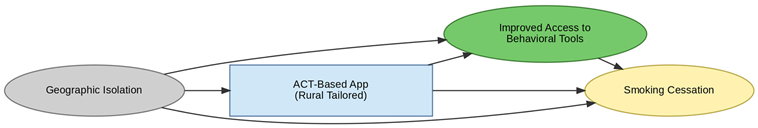

The intervention layer identifies modality-specific pathways that align with the aforementioned upstream constraints. Geographic isolation directs individuals toward Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) based mobile applications, facilitating access to evidence-based tools. Digital access limitations and low health literacy channel participants toward social media and storytelling-based interventions that enhance message relevance and peer engagement. Psychological barriers are associated with the use of quitline services, which mitigate in-person access limitations. Each intervention node is linked to distinct mechanisms of action, highlighting how delivery modality and contextual appropriateness influence downstream behavioral change.

3.3.3. Mechanistic: Mediators of Change

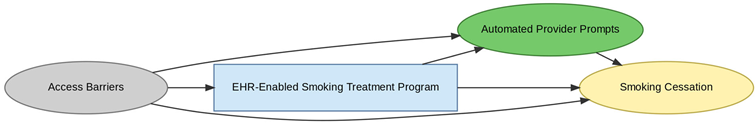

Centrally positioned within the iDAG are mechanistic nodes such as improved coping skills, empowerment, social support, and behavioral nudges that mediate the causal effects of interventions. Their centrality underscores their critical role in translating intervention exposure into behavioral outcomes. CBT, NRT, and ACT-based approaches all converge on coping skill enhancement, suggesting strong theoretical coherence across modalities. Mechanisms such as automated provider prompts in electronic health record (EHR) systems and online peer engagement in digital platforms are intervention-specific, reinforcing the importance of causal pathway specificity in understanding intervention efficacy.

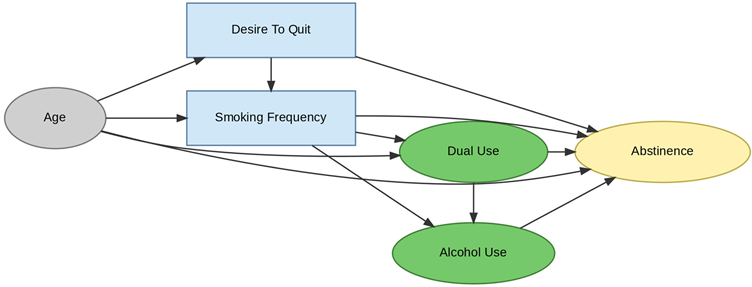

3.3.4. Behavioral: Modifiable Risk Factors

The behavioral layer comprises dynamic, modifiable mediators, including smoking frequency, dual use (cigarettes and vaping), alcohol consumption, and motivation to quit. These behavioral constructs link psychological mechanisms to cessation outcomes and capture known confounding relationships. For example, dual use and alcohol consumption often co-occur and collectively diminish cessation likelihood. Age and motivation to quit further moderate these dynamics, highlighting the complex feedback between readiness to change, behavioral risk factors, and cessation success.

3.3.5. Outcome: Smoking Cessation

At the terminal point of the IDAG lies the smoking cessation node, where all causal pathways converge. Cessation outcomes are influenced by both direct intervention effects and indirect pathways mediated through behavioral and psychological mechanisms. Notably, no upstream determinant connects directly to cessation without traversing intermediate nodes, underscoring the mediated and multistage nature of effective tobacco control strategies.

4. Discussion

The integrated ESC-DAG establishes complex and multifactorial causal pathways that affect tobacco cessation intervention outcomes in the United States. One of the key identified barriers was structural, i.e., socioeconomic disadvantage, digital inequities, and rurality, which affected access to interventions. These factors affected both the direct cessation outcomes and indirect mediators, including motivation, engagement, and treatment adherence. One of the key identified facilitators was provider engagement, emphasizing that healthcare system interactions remain crucial for cessation success.

The findings of this study are consistent with emerging international evidence emphasizing the importance of cultural tailoring and digital innovation in smoking cessation interventions. For instance, Bhatt et al. (2024) demonstrated that culturally and disease-specific multi-component interventions significantly improved cessation rates among patients attending non-communicable disease clinics in India, supporting the present study’s identification of cultural adaptation as a key facilitator [45]. Similarly, Okpako et al. (2024) found substantial interest in digital and virtual-reality–based cessation supports among smokers in Great Britain, reinforcing our DAG-derived conclusion that digital access and engagement pathways are pivotal to enhancing intervention reach and adherence [46].

Some of the underexplored pathways, i.e., cultural tailoring, minority stress, and stigma, emphasize crucial gaps in existing evidence as only a few edges supported these domains from existing empirical studies. This study has several limitations. First, the evidence base was restricted to studies conducted in the United States, which may limit the generalizability of the resulting DAG to other healthcare or cultural contexts. Second, as the synthesis relied on published quantitative studies, potential publication bias cannot be fully excluded, despite the comprehensive search and inclusion strategy of the source review. Third, challenges arose in harmonizing conceptually overlapping constructs such as stress, depression, and minority stress. While constructs were consolidated using theoretical and empirical alignment, this harmonization may have reduced specificity in some psychosocial pathways.

4.1. Methodological Contributions

This study demonstrates the added value of the ESC-DAG methodology over traditional narrative or systematic reviews. By translating empirical evidence into a unified graphical model, we identified confounders, mediators, and moderators that are often overlooked in conventional statistical synthesis. Unlike meta-analysis, which emphasizes effect sizes, ESC-DAG enables researchers to map relationships across diverse study designs and uncover the underlying causal architecture. This methodological innovation is particularly valuable for complex behavioral and health services interventions, where context and interaction effects are critical.

4.2. Policy and Practice Implications

The integrated DAG provides insights for designing equity-focused and targeted cessation interventions. It encompasses digital equity, socio-economic support, provider engagement, and cultural tailoring, which reinforces the need for multi-level interventions addressing not only individual motivation but also other systemic barriers to healthcare access.

The integrated DAG could be utilized to guide confounder adjustment in observational studies of tobacco cessation interventions by applying DAG-informed simulation models to predict the potential impact of scaling specific strategies. It could guide the design of tailored digital platforms that account for motivation levels, literacy, and socio-economic context. Beyond visualizing causal relationships, the integrated ESC-DAG can serve as a strategic framework to prioritize interventions and resource allocation. For instance, structural determinants such as digital inequities and socioeconomic disadvantage occupy upstream positions in the DAG, influencing multiple downstream mediators including motivation, engagement, and access to cessation support. Addressing these upstream nodes through digital equity initiatives (e.g., subsidized internet access, device provision, digital literacy training) or financial support mechanisms (e.g., free NRT, incentive-based programs) is likely to yield broader system-level impact than focusing solely on individual-level behavior change. Conversely, downstream facilitators such as provider engagement and motivational support can be targeted for shorter-term implementation or pilot interventions.

The DAG also provides a foundation for future simulation modeling and quasi-experimental trials by identifying high-priority mediators for targeted testing. For example, a comparative trial could evaluate whether addressing digital inequities produces greater cessation gains than financial incentive programs within resource-constrained settings. Furthermore, by mapping interdependencies between structural and psychosocial factors, the DAG can guide the sequencing of interventions, informing whether structural interventions should precede or accompany behavioral supports.

5. Conclusions

This study extends the methodological application of ESC-DAG to tobacco cessation research, synthesizing evidence from 35 studies into a unified causal framework. The integrated DAG highlights the central role of structural inequities, digital access, and provider engagement in shaping cessation outcomes.

By visualizing these relationships, our analysis demonstrates how DAGs can inform statistical modeling, guide intervention design, and prioritize equity-oriented policy solutions. Future research should build on this framework through simulation studies, quasi-experimental evaluations, and longitudinal designs to test targeted strategies for reducing disparities in cessation uptake.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S. and N.P.; methodology, N.P., S.S. and J.I.; software, N.P.; validation S.S., J.I. and N.P.; formal analysis, S.S., N.P. and J.I.; investigation, S.S., J.I. and N.P.; resources, writing—original draft preparation, N.P. and S.S.; writing—review and editing, N.P., S.S. and J.I.; visualization, N.P., S.S. and J.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable as a review study of secondary data where no human subjects were involved.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was generated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Translation stage results of included studies.

Table A1.

Translation stage results of included studies.

| Edge | Temporality | Face Validity | Recourse to Theory | Final Action | Pathway Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age → Desire to Quit | Valid | Plausible | Supported in behavioral models | Retain | Confounder |

| Age → Smoking Frequency | Valid | Valid | Risk exposure literature supports | Retain | Confounder |

| Age → Dual Use | Valid | Supported by age-based substance use research | Yes | Retain | Confounder |

| Smoking Frequency → Dual Use | Valid | Strong behavioral linkage | Supported | Retain | Mediator |

| Desire to Quit → Smoking Frequency | Valid | Valid | TTM & quit models | Retain | Mediator |

| Dual Use → Alcohol Use | Valid | Comorbid use theory | Strong support | Retain | Mediator |

| Dual Use → Smoking Cessation | Valid | Plausible | Mixed evidence | Retain (flag for sensitivity) | Mediator |

| Alcohol Use → Smoking Cessation | Valid | Mixed support | Substance relapse theory | Retain | Mediator |

| Cognitive Behavioral Therapy → Improved Coping | Valid | Strong support | Core of CBT | Retain | Mediator |

| Improved Coping Skills → Smoking Cessation | Valid | Plausible | Strong in addiction theory | Retain | Mediator |

| Distress → Cognitive Behavioral Therapy | Valid | Yes | Routine clinical pathway | Retain | Confounder |

| Distress → 8-Week Nicotine Patch | Valid | Common clinical response | Yes | Retain | Confounder |

| Distress → Improved Coping Skills | Valid | Established stress models | Yes | Retain | Confounder |

| Geographic Isolation → ACT-Based App | Valid | Yes | Rural access models | Retain | Confounder |

| ACT-Based App → Improved Access to Tools | Valid | Strong | Valid | Retain | Mediator |

| Improved Access to Tools → Smoking Cessation | Valid | Behavioral support theory | Yes | Retain | Mediator |

| Barriers in Young Adults → Text Msg Intervention | Valid | Known access issue | Valid | Retain | Confounder |

| Text Msg Intervention → Behavioral Nudges | Valid | Behaviorism support | Yes | Retain | Mediator |

| Behavioral Nudges → Smoking Cessation | Valid | Supported | Yes | Retain | Mediator |

| Cultural Barriers → Storytelling Video | Valid | Strong support | Yes | Retain | Confounder |

| Health Literacy → Storytelling Video | Valid | Supported | Yes | Retain | Confounder |

| Storytelling Video → Message Relevance | Valid | Yes | Yes | Retain | Mediator |

| Message Relevance → Smoking Cessation | Valid | Plausible | Yes | Retain | Mediator |

| Health Literacy → Empowerment | Valid | Supported | Yes | Retain | Mediator |

| Empowerment → Smoking Cessation | Valid | Supported | Yes | Retain | Mediator |

| Access Barriers → EHR Intervention | Valid | Structural logic | Yes | Retain | Confounder |

| EHR Intervention → Provider Prompts | Valid | Plausible | Systematic evidence | Retain | Mediator |

| Provider Prompts → Smoking Cessation | Valid | Workflow behavior support | Yes | Retain | Mediator |

| Digital Access Barriers → Social Media Intervention | Valid | Digital divide evidence | Yes | Retain | Confounder |

| Social Media Intervention → Online Peer Support | Valid | Plausible | Yes | Retain | Mediator |

| Online Peer Support → Smoking Cessation | Valid | Peer-based models | Yes | Retain | Mediator |

| Rural Area → CHW + NRT | Valid | Intervention targeting | Yes | Retain | Confounder |

| Low Health Resources → CHW + NRT | Valid | Targeting underserved | Yes | Retain | Confounder |

| CHW + NRT → Social Support | Valid | Social pathway logic | Yes | Retain | Mediator |

| Social Support → Smoking Cessation | Valid | Strong evidence | Yes | Retain | Mediator |

| Psychological Barriers → Quitline + Treatment | Valid | Valid | Yes | Retain | Confounder |

| Quitline + Treatment → Smoking Cessation | Valid | Supported | Strong theoretical support | Retain | Mediator |

Table A2.

Operational definition of key constructs harmonized in the iDAG.

Table A2.

Operational definition of key constructs harmonized in the iDAG.

| Harmonized Construct | Operational Definition | Distinct From | Source Constructs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological Distress | Emotional or mental strain interfering with readiness to quit or treatment engagement | Minority Stress, Depression | “mental health”, “stress”, “emotional burden” |

| Minority Stress | Stressors from identity-based discrimination, stigma, or exclusion | General Stress, Socioeconomic Disadvantage | “racial stigma”, “LGBTQ discrimination”, “social bias” |

| Digital Access Barriers | Limited access to or usability of digital cessation tools due to device, connectivity, or literacy gaps | Health Literacy, Technological Engagement | “no smartphone”, “low digital literacy”, “poor access” |

| Socioeconomic Disadvantage | Structural deprivation limiting intervention access or adherence | Minority Stress, Rural Residence | “low income”, “unemployment”, “housing instability” |

| Provider Engagement | Direct action by healthcare providers to recommend, facilitate, or reinforce cessation | Passive Access, System Navigation | “counseling”, “EHR trigger”, “referral to services” |

| Coping Skills Enhancement | Mechanisms that strengthen emotional self-regulation and relapse prevention | Empowerment, Support | “stress management”, “resilience training”, “CBT” |

| Motivation to Quit | Individual’s readiness and intention to initiate cessation | Self-Efficacy, Knowledge | “desire to quit”, “stage of change”, “quit intention” |

| Social Support | External encouragement or assistance from family, peers, or community | Provider Engagement, Empowerment | “family support”, “peer encouragement”, “group sessions” |

| Mobile App Interventions | Use of structured, evidence-based cessation content delivered via smartphone apps | Quitlines, Storytelling | “ACT app”, “digital CBT”, “motivational text” |

| Financial Incentives | Monetary or material rewards linked to cessation behavior | Social Support, Intrinsic Motivation | “cash rewards”, “gift cards for abstinence” |

References

- Leventhal, A.M.; Dai, H.; Higgins, S.T. Smoking Cessation Prevalence and Inequalities in the United States: 2014–2019. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2021, 114, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, K.G.; Volk, R.J. Disparities in Receipt of Smoking Cessation Assistance Within the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2215681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapoint, D.N.; Quigley, B.; Monegro, A.F. Health Care Disparities and Smoking Cessation Counseling: A Retrospective Study on Urban and Non-Urban Populations. Chest 2023, 164, A6390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanFrank, B.; Malarcher, A.; Cornelius, M.E.; Schecter, A.; Jamal, A.; Tynan, M. Adult Smoking Cessation—United States, 2022. In Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR); Centers for Disease Control MMWR Office: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Goodin, A.; Talbert, J.; Freeman, P.R.; Hahn, E.J.; Fallin-Bennett, A. Appalachian Disparities in Tobacco Cessation Treatment Utilization in Medicaid. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2020, 15, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, S.; Inungu, J.; Jahanfar, S. Barriers and Facilitators of Tobacco Cessation Interventions at the Population and Healthcare System Levels: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Karimi, S.M.; Little, B.; Egger, M.; Antimisiaris, D. Applying Evidence Synthesis for Constructing Directed Acyclic Graphs to Identify Causal Pathways Affecting U.S. Early-Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment Receipt and Overall Survival. Therapeutics 2024, 1, 64–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenland, S.; Pearl, J.; Robins, J.M. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology 1999, 10, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, K.D.; McCann, M.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Thomson, H.; Green, M.J.; Smith, D.J.; Lewsey, J.D. Evidence Synthesis for Constructing Directed Acyclic Graphs (ESC-DAGs): A Novel and Systematic Method for Building Directed Acyclic Graphs. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 49, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Textor, J.; van der Zander, B.; Gilthorpe, M.S.; Liśkiewicz, M.; Ellison, G.T. Robust causal inference using directed acyclic graphs: The R package “dagitty”. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 1887–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aday, L.A.; Begley, C.E.; Larison, D.R.; Slater, C.H.; Richard, A.J.; Montoya, I.D. A Framework for Assessing the Effectiveness, Efficiency, and Equity of Behavioral Healthcare—PubMed. Am. J. Manag. Care 1999, 5, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Baggett, T.P.; Chang, Y.; Yaqubi, A.; McGlave, C.; Higgins, S.T.; Rigotti, N.A. Financial Incentives for Smoking Abstinence in Homeless Smokers: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2018, 20, 1442–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.R.; Marino, M.; Ezekiel-Herrera, D.; Schmidt, T.; Angier, H.; Hoopes, M.J.; DeVoe, J.E.; Heintzman, J.; Huguet, N. Tobacco Cessation in Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansion States Versus Non-expansion States. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020, 22, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bricker, J.B.; Santiago-Torres, M.; Mull, K.E.; Sullivan, B.M.; David, S.P.; Schmitz, J.; Stotts, A.; Rigotti, N.A. Do medications increase the efficacy of digital interventions for smoking cessation? Secondary results from the iCanQuit randomized trial. Addiction 2024, 119, 664–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, D.R.; Burtner, J.L.; Borrelli, B.; Heeren, T.C.; Evans, T.; Davine, J.A.; Greenbaum, J.; Scarpaci, M.; Kane, J.; Rees, V.W.; et al. Twelve-Month Outcomes of a Group-Randomized Community Health Advocate-Led Smoking Cessation Intervention in Public Housing. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2018, 20, 1434–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Anderson, C.M.; Babb, S.D.; Frank, R.; Wong, S.; Kuiper, N.M.; Zhu, S.-H. Evaluation of the Asian Smokers’ Quitline: A Centralized Service for a Dispersed Population. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 60, S154–S162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, B.A.; Reeder, K.M.; TerBeek, E.G.; Fiore, M.C.; Baker, T.B. Motivating Low Socioeconomic Status Smokers to Accept Evidence-Based Smoking Cessation Treatment: A Brief Intervention for the Community Agency Setting. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2015, 17, 1002–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, B.N.; Nair, U.S.; Davis, S.M.; Rodriguez, D. Increasing Home Smoking Restrictions Boosts Underserved Moms’ Bioverified Quit Success. Am. J. Health Behav. 2019, 43, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahne, J.; Wahlquist, A.E.; Smith, T.T.; Carpenter, M.J. The di fferential impact of nicotine replacement therapy sampling on cessation outcomes across established tobacco disparities groups. Prev. Med. 2020, 136, 106096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.S.; van Ryn, M.; Nelson, D.; Burgess, D.J.; Thomas, J.L.; Saul, J.; Clothier, B.; Nyman, J.A.; Hammett, P.; Joseph, A.M. Proactive tobacco treatment offering free nicotine replacement therapy and telephone counselling for socioeconomically disadvantaged smokers: A randomised clinical trial. Thorax 2016, 71, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiatsatos, P.; Soybel, A.; Jassal, M.; Cruz, S.A.P.; Spartin, C.; Shaw, K.; Cunningham, J.; Kanarek, N.F. Tobacco treatment clinics in urban public housing: Feasibility and outcomes of a hands-on tobacco dependence service in the community. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A.L.; Papandonatos, G.D.; Cha, S.; Erar, B.; Amato, M.S. Improving Adherence to Smoking Cessation Treatment: Smoking Outcomes in a Web-based Randomized Trial. Ann. Behav. Med. 2018, 52, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpern, S.D.; French, B.; Small, D.S.; Saulsgiver, K.; Harhay, M.O.; Audrain-McGovern, J.; Loewenstein, G.; Brennan, T.A.; Asch, D.A.; Volpp, K.G. Randomized Trial of Four Financial-Incentive Programs for Smoking Cessation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2108–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heffner, J.L.; Mull, K.E.; Watson, N.L.; McClure, J.B.; Bricker, J.B. Long-Term Smoking Cessation Outcomes for Sexual Minority Versus Nonminority Smokers in a Large Randomized Controlled Trial of Two Web-Based Interventions. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020, 22, 1596–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickman, I.I.I.N.J.; Delucchi, K.L.; Prochaska, J.J. Treating Tobacco Dependence at the Intersection of Diversity, Poverty, and Mental Illness: A Randomized Feasibility and Replication Trial. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2015, 17, 1012–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, S.T.; Plucinski, S.; Orr, E.; Nighbor, T.D.; Coleman, S.R.M.; Skelly, J.; DeSarno, M.; Bunn, J. Randomized clinical trial examining financial incentives for smoking cessation among mothers of young children and possible impacts on child secondhand smoke exposure. Prev. Med. 2023, 176, 107651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, M.W.; Miller, D.B.; Saldivar, E.; Mitchell, C.; Johnson, L.; Burns, M.; Huang, M.-C. Randomized Controlled Trial Testing a Video-Text Tobacco Cessation Intervention Among Economically Disadvantaged African American Adults. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2021, 35, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamke, K.; Grenen, E.; Robinson, C.; El-Toukhy, S. Dropout and Abstinence Outcomes in a National Text Messaging Smoking Cessation Intervention for Pregnant Women, SmokefreeMOM: Observational Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e14699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendzor, D.E.; Businelle, M.S.; Frank-Pearce, S.G.; Waring, J.J.C.; Chen, S.; Hebert, E.T.; Swartz, M.D.; Alexander, A.C.; Sifat, M.S.; Boozary, L.K.; et al. Financial Incentives for Smoking Cessation Among Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Adults A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2418821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkvliet, J.L.; Wey, H.; Fahrenwald, N.L. Cessation Among State Quitline Participants with a Mental Health Condition. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2015, 17, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurti, A.N.; Tang, K.; Bolivar, H.A.; Evemy, C.; Medina, N.; Skelly, J.; Nighbor, T.; Higgins, S.T. Smartphone-based financial incentives to promote smoking cessation during pregnancy: A pilot study. Prev. Med. 2020, 140, 106201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Contrera Avila, J.; Ahluwalia, J.S. Differences in Cessation Attempts and Cessation Methods by Race/ethnicity Among US Adult Smokers, 2016–2018. Addict. Behav. 2023, 137, 107523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Miller, S.M.; Wen, K.-Y.; Hui, S.A.; Roussi, P.; Hernandez, E. Cognitive-behavioral intervention to promote smoking cessation for pregnant and postpartum inner city women. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 38, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mays, D.; Johnson, A.C.; Phan, L.; Sanders, C.; Shoben, A.; Tercyak, K.P.; Wagener, T.L.; Brinkman, M.C.; Lipkus, I.M. Tailored Mobile Messaging Intervention for Waterpipe Tobacco Cessation in Young Adults: A Randomized Trial. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 1686–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meernik, C.; McCullough, A.; Ranney, L.; Walsh, B.; Goldstein, A.O. Evaluation of Community-Based Cessation Programs: How Do Smokers with Behavioral Health Conditions Fare? Community Ment. Health J. 2018, 54, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidrine, J.I.; Sutton, S.K.; Wetter, D.W.; Shih, Y.-C.T.; Ramondetta, L.M.; Elting, L.S.; Walker, J.L.; Smith, K.M.; Frank-Pearce, S.G.; Li, Y.; et al. Efficacy of a Smoking Cessation Intervention for Survivors of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia or Cervical Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 2779–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wewers, M.E.; Shoben, A.; Conroy, S.; Curry, E.; Ferketich, A.K.; Murray, D.M.; Nemeth, J.; Wermert, A. Effectiveness of Two Community Health Worker Models of Tobacco Dependence Treatment Among Community Residents of Ohio Appalachia. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2017, 19, 1499–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.C.; Meacham, M.C.; Nguyen, N.; Ramo, D.; Ling, P.M. Factors Associated With Abstinence Among Young Adult Smokers Enrolled in a Real-world Social Media Smoking Cessation Program. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2024, 26, S27–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, M.W.; Calixte-Civil, P.; Verzijl, C.; Brandon, K.O.; Asfar, T.; Koru-Sengul, T.; Antoni, M.H.; Lee, D.J.; Simmons, V.N.; Brandon, T.H. Associations between perceived racial discrimination and tobacco cessation among diverse treatment seekers. Ethn. Dis. 2020, 30, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, D.E.; Baker, T.B.; Zehner, M.E.; Adsit, R.T.; Kim, N.; Zwaga, D.; Coates, K.; Wallenkamp, H.; Nolan, M.; Steiner, M.; et al. A Comprehensive Electronic Health Record-Enabled Smoking Treatment Program: Evaluating Reach and Effectiveness in Primary Care in a Multiple Baseline Design. Prev. Med. 2022, 165, 107101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuter, M.W.; Garg, R.; Fu, Q.; Caburnay, C.; Thompson, T.; Roberts, C.; Sandheinrich, D.; Javed, I.; Wolff, J.M.; Butler, T.; et al. Helping Low-Income Smokers Quit: Findings from a Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Specialized Quitline Services with and Without Social Needs Navigation. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2023, 23, 100529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torres, M.; Mull, K.E.; Sullivan, B.M.; Ferketich, A.K.; Bricker, J.B. Efficacy of an acceptance and commitment therapy-based smartphone application for helping rural populations quit smoking: Results from the iCanQuit randomized trial. Prev. Med. 2022, 157, 107008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torres, M.; Mull, K.E.; Sullivan, B.M.; Kwon, D.M.; Henderson, P.N.; Nelson, L.A.; Patten, C.A.; Bricker, J.B. Efficacy and Utilization of Smartphone Applications for Smoking Cessation Among American Indians and Alaska Natives: Results From the iCanQuit Trial. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2022, 24, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb Hooper, M.; Kolar, S.K. Distress, race/ethnicity and smoking cessation in treatment-seekers: Implications for disparity elimination. Addiction 2015, 110, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, G.; Goel, S.; Yadav, S.K.; Patial, A.; Medhi, B.; Grover, S.; Attri, S.; Kaur, R.; Singh, G.; Gill, S.S. A Randomised Controlled Trial to Evaluate the Effectiveness of a Culture and Disease-Specific, Patient-Centric Multi-Component Tobacco Cessation Intervention Package for the Patients Attending Non-Communicable Disease Clinics in PUNJAB. India Psychol. Health 2025, 40, 1497–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpako, T.; Kale, D.; Perski, O.; Brown, J. Prevalence and Characteristics of Smokers Interested in Using Virtual Reality for Encouraging Smoking Cessation: A Representative Population Survey in Great Britain. BMC Digit. Health 2024, 2, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).