Perceived Stress Profiles Among Italian University Students: A Multivariate Approach

Highlights

- Italian university students show moderate–high perceived stress; academic demands are the predominant stressors.

- Higher stress is observed in women, younger and first-year students, and those in Health Sciences/STEM, whereas lower stress/better coping is observed in older and postgraduate students and in Southern/Islands; private universities show higher academic pressure.

- Use early screening with validated instruments such as the IPSS-R to identify at-risk groups and provide targeted interventions.

- Implement institutional measures (workload/assessment review, counseling, peer support), prioritizing first-year and high-pressure programs.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Sample and Data Collection

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Statistical Analyses

2.6. Transparency and Openness

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

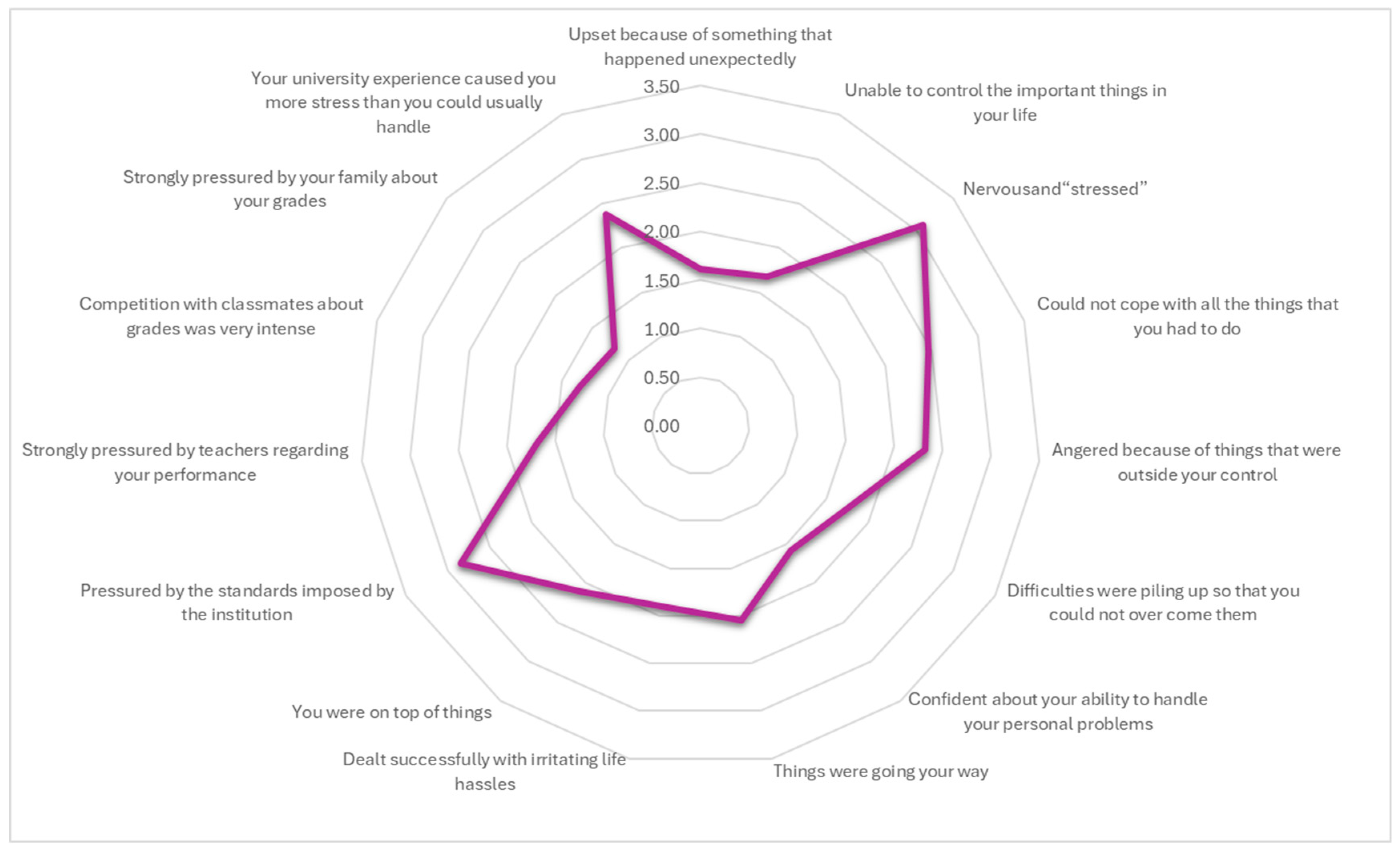

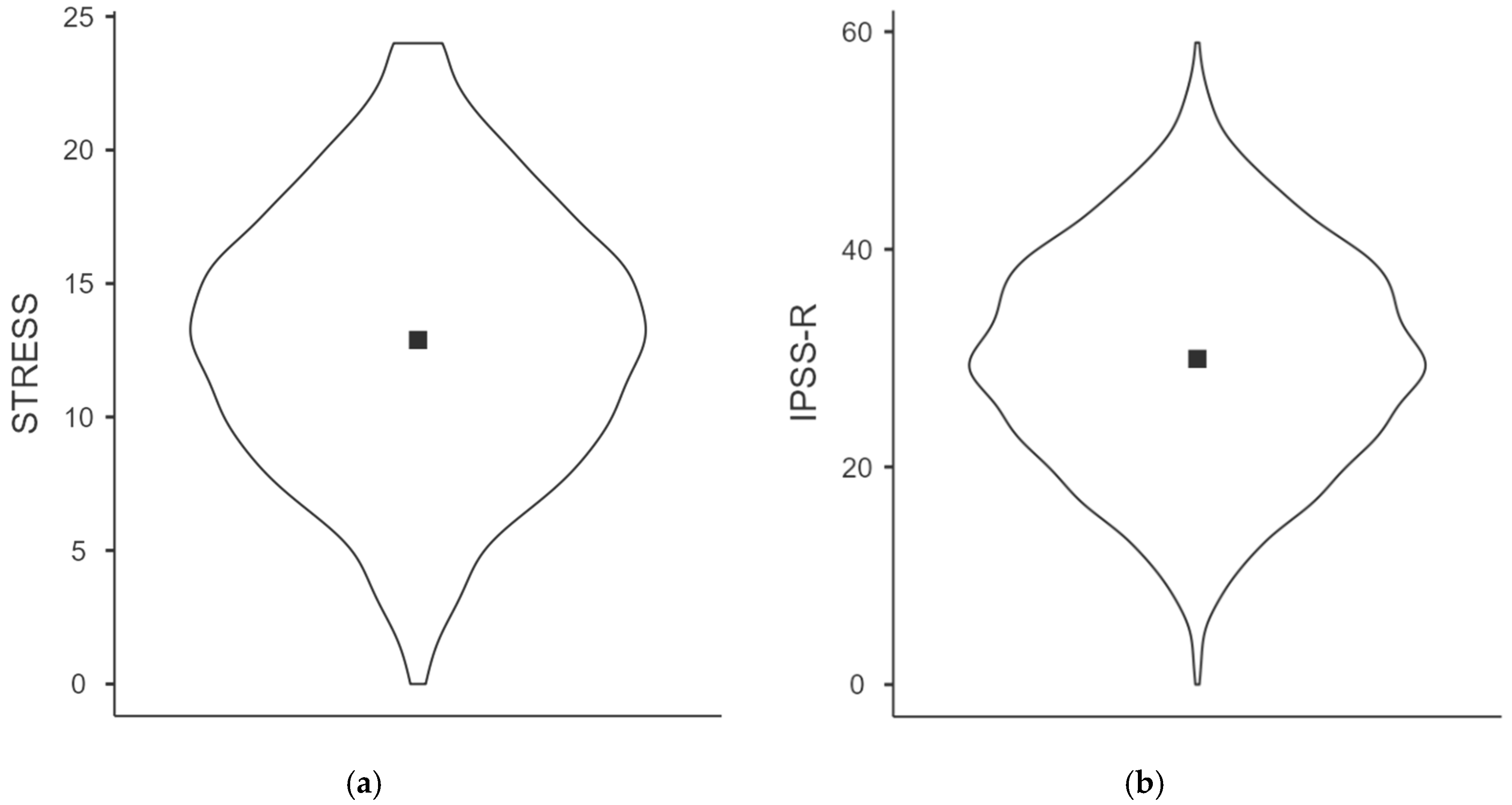

3.2. Stress and Coping Profiles

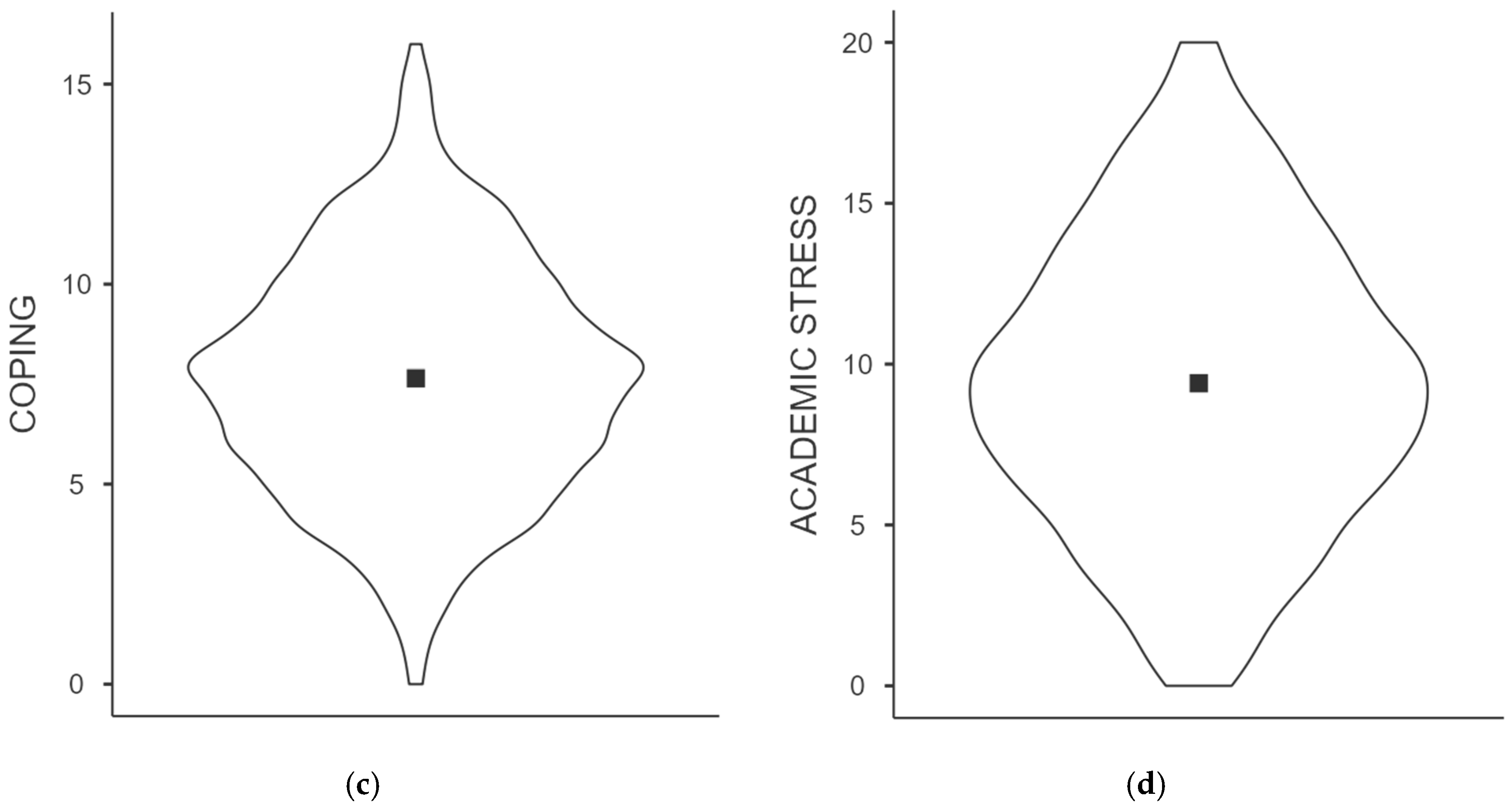

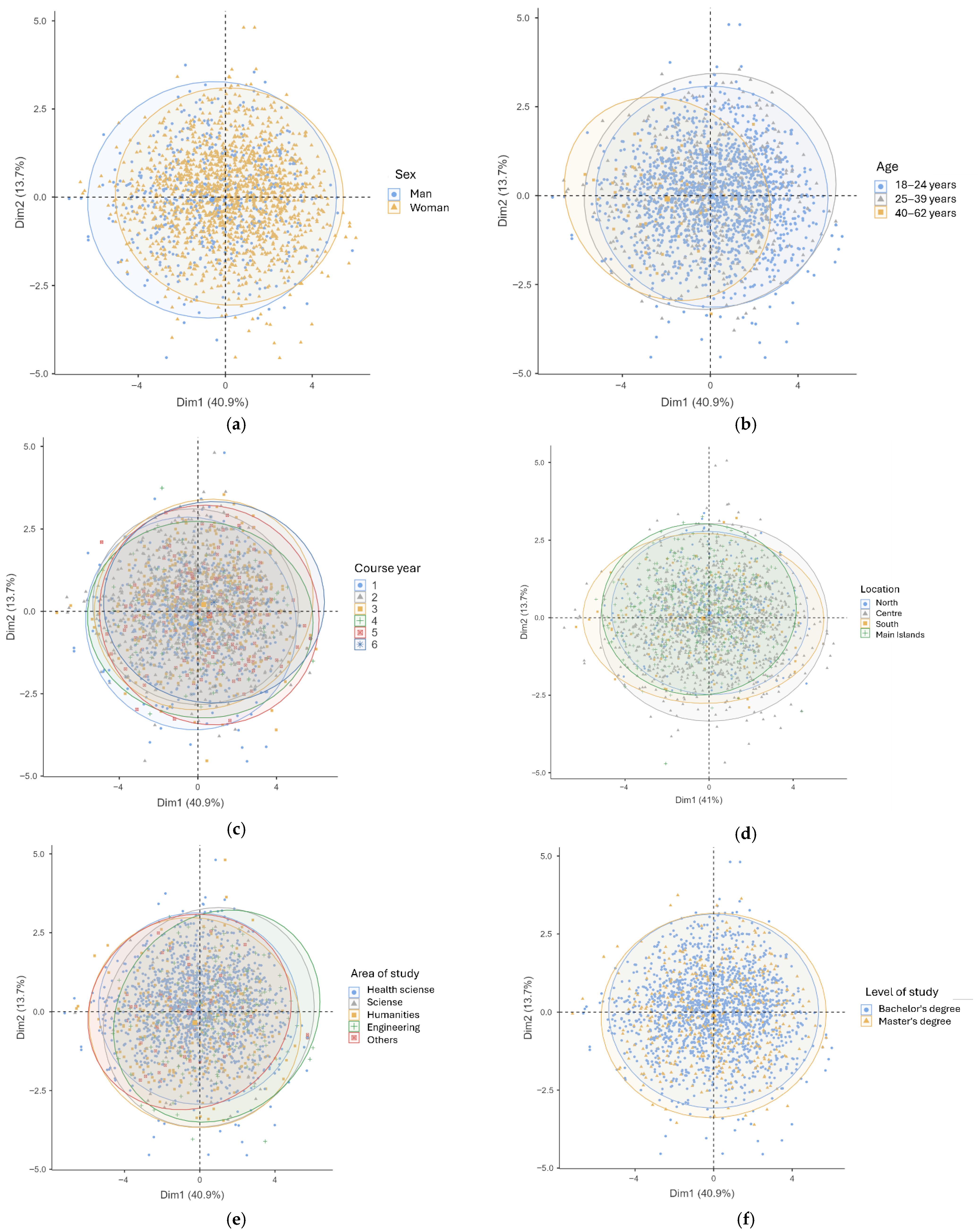

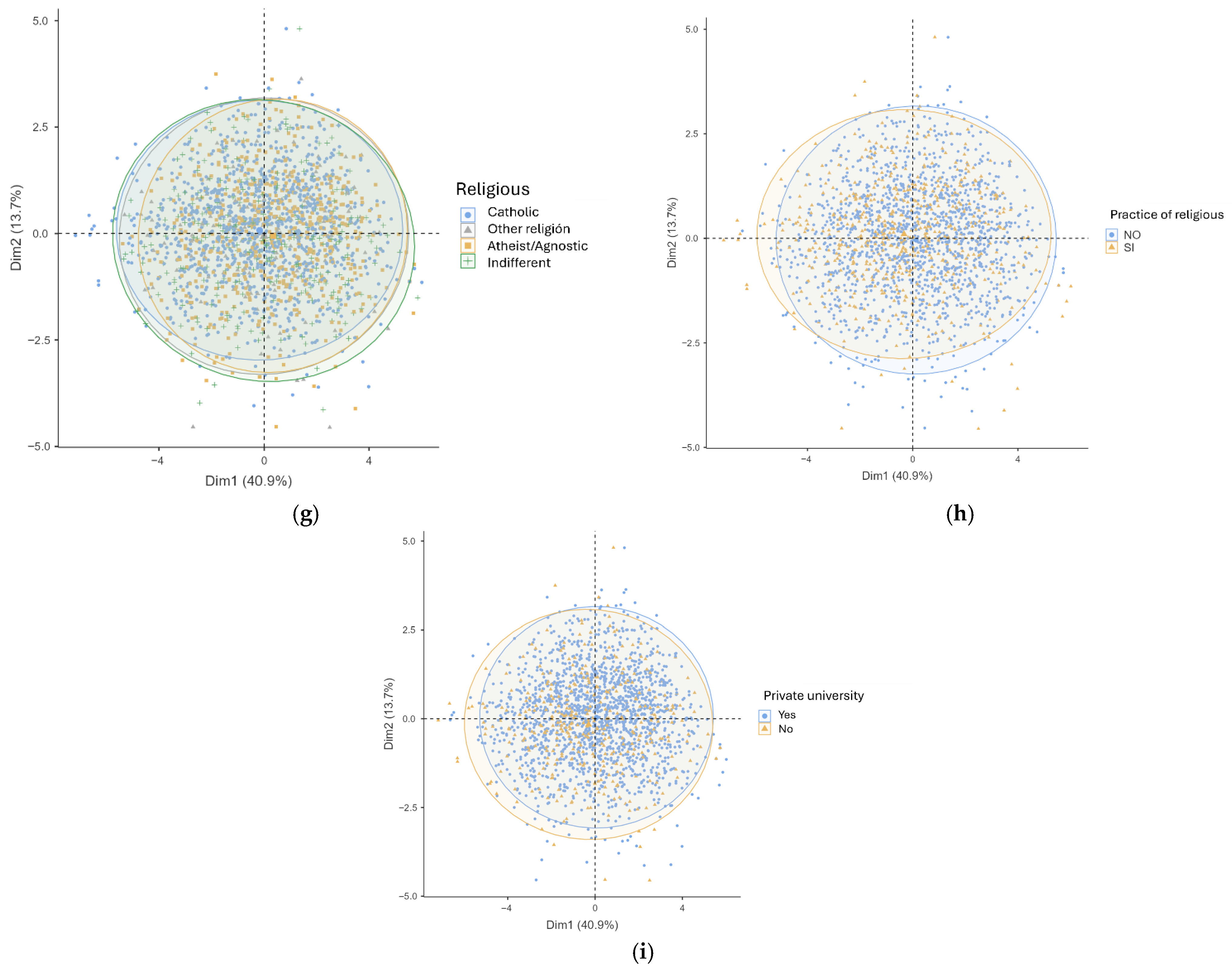

3.3. Principal Component Analysis

3.4. Group Comparisons

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IPSS-R | Italian Perceived Stress Scale—Revised |

| PSS | Perceived Stress Scale |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| STROBE | Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| HPA | Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal (axis) |

| SAM | Sympathetic–Adrenal–Medullary (system) |

| STEM | Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| CECRI | Center of Excellence for Nursing Scholarship (Rome, Italy) |

Appendix A

References

- Obbarius, N.; Fischer, F.; Liegl, G.; Obbarius, A.; Rose, M. A Modified Version of the Transactional Stress Concept According to Lazarus and Folkman Was Confirmed in a Psychosomatic Inpatient Sample. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 584333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.L.S.; Chow, P.P.K.; Wong, F.M.F.; Ho, M.M. Associations among stressors, perceived stress, and psychological distress in nursing students: A mixed methods longitudinal study of a Hong Kong sample. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1234354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, S.S.; Kemeny, M.E. Acute Stressors and Cortisol Responses: A Theoretical Integration and Synthesis of Laboratory Research. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 355–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Physiology and Neurobiology of Stress and Adaptation: Central Role of the Brain. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 873–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavich, G.M.; Irwin, M.R. From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: A social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 774–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Janicki-Deverts, D.; Miller, G.E. Psychological Stress and Disease. JAMA 2007, 298, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccarino, V.; Bremner, J.D. Stress and cardiovascular disease: An update. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2024, 21, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosalski, R.; Siedlinski, M.; Neves, K.B.; Monaco, C. Editorial: The interplay between oxidative stress, immune cells and inflammation in cardiovascular diseases. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1385809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Bian, F.; Zhu, Y. The relationship between social support and academic engagement among university students: The chain mediating effects of life satisfaction and academic motivation. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huguenel, B.M.; Conley, C.S. Transitions to Higher Education. In The Encyclopedia of Child and Adolescent Development; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Barbayannis, G.; Bandari, M.; Zheng, X.; Baquerizo, H.; Pecor, K.W.; Ming, X. Academic Stress and Mental Well-Being in College Students: Correlations, Affected Groups, and COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 886344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Tu, C.C.; Wang, Z.; Hao, D.; Huang, X. Potential effect of social support on perceived stress and anxiety in college students during public health crisis: Multiple interactions of gender. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0319799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.R.; Meyers, S.A.; Beidas, R.S. The relationship between financial strain, perceived stress, psychological symptoms, and academic and social integration in undergraduate students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2016, 64, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasr, R.; Rahman, A.A.; Haddad, C.; Nasr, N.; Karam, J.; Hayek, J.; Ismael, I.; Swaidan, E.; Salameh, P.; Alami, N. The impact of financial stress on student wellbeing in Lebanese higher education. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maymon, R.; Hall, N.C. A Review of First-Year Student Stress and Social Support. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrella-Proaño, A.; Rivadeneira, M.F.; Alvarado, J.; Murtagh, M.; Guijarro, S.; Alomoto, L.; Cañarejo, G. Anxiety and depression in first-year university students: The role of family and social support. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1462948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedewy, D.; Gabriel, A. Examining perceptions of academic stress and its sources among university students: The Perception of Academic Stress Scale. Health Psychol. Open 2015, 2, 2055102915596714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, Í.J.S.; Pereira, R.; Freire, I.V.; de Oliveira, B.G.; Casotti, C.A.; Boery, E.N. Stress and Quality of Life Among University Students: A Systematic Literature Review. Health Prof. Educ. 2018, 4, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monserrat-Hernández, M.; Checa-Olmos, J.C.; Arjona-Garrido, Á.; López-Liria, R.; Rocamora-Pérez, P. Academic Stress in University Students: The Role of Physical Exercise and Nutrition. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leombruni, P.; Corradi, A.; Moro, G.L.; Acampora, A.; Agodi, A.; Celotto, D.; Chironna, M.; Cocchio, S.; Cofini, V.; D’errico, M.M.; et al. Stress in Medical Students: PRIMES, an Italian, Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portoghese, I.; Porru, F.; Galletta, M.; Campagna, M.; Burdorf, A. Stress among medical students: Factor structure of the University Stress Scale among Italian students. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondo, M.; Sechi, C.; Cabras, C. Psychometric evaluation of three versions of the Italian Perceived Stress Scale. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 1884–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piredda, M.; Cascio, A.L.; Marchetti, A.; Campanozzi, L.; Pellegrino, P.; Mondo, M.; Petrucci, G.; Latina, R.; De Maria, M.; Alvaro, R.; et al. Development and Psychometric Testing of Perfectionism Inventory to Assess Perfectionism and Academic Stress in University Students: A Cross-Sectional Multi-Centre Study. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörnell, A.; Berg, C.; Forsum, E.; Larsson, C.; Sonestedt, E.; Åkesson, A.; Lachat, C.; Hawwash, D.; Kolsteren, P.; Byrnes, G.; et al. Perspective: An Extension of the STROBE Statement for Observational Studies in Nutritional Epidemiology (STROBE-nut): Explanation and Elaboration. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 652–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Participants. JAMA 2025, 333, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Online Statistics Calculator. Hypothesis Testing T-TC-SRCA of VCAnalysis. Online Statistics Calculator. Hypothesis Testing, T-Test, Chi-Square, Regression, Correlation, Analysis of Variance, Cluster Analysis. 2024. Available online: https://datatab.net/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cid, L.; Monteiro, D.; Teixeira, D.S.; Evmenenko, A.; Andrade, A.; Bento, T.; Vitorino, A.; Couto, N.; Rodrigues, F. Assessment in Sport and Exercise Psychology: Considerations and Recommendations for Translation and Validation of Questionnaires. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 806176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorndike, R.L. Who Belongs in the Family? Psychometrika 1953, 18, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, N.; Oberhoffer-Fritz, R.; Reiner, B.; Schulz, T. Stress, student burnout and study engagement—A cross-sectional comparison of university students of different academic subjects. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Jorge, D.; Boutaba-Alehyan, M.; González-Contreras, A.I.; Pérez-Pérez, I. Examining the effects of academic stress on student well-being in higher education. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Yang, G.; Lin, Z.; Ning, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Wong, C.U.I. The impact of academic burnout on academic achievement: A moderated chain mediation effect from the Stimulus-Organism-Response perspective. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1559330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slimmen, S.; Timmermans, O.; Mikolajczak-Degrauwe, K.; Oenema, A. How stress-related factors affect mental wellbeing of university students A cross-sectional study to explore the associations between stressors, perceived stress, and mental wellbeing. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puigbó, J.; Edo, S.; Rovira, T.; Limonero, J.T.; Fernández-Castro, J. Influencia de la inteligencia emocional percibida en el afrontamiento del estrés cotidiano. Ansiedad Estrés 2019, 25, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nespereira-Campuzano, T.; Vázquez-Campo, M. Inteligencia emocional y manejo del estrés en profesionales de Enfermería del Servicio de Urgencias hospitalarias. Enferm. Clin. 2017, 27, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pointon-Haas, J.; Waqar, L.; Upsher, R.; Foster, J.; Byrom, N.; Oates, J. A systematic review of peer support interventions for student mental health and well-being in higher education. BJPsych Open 2023, 10, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mize, J.L. Depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms and coping strategies in the context of the sudden course modality shift in the Spring 2020 semester. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 43, 3944–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulick, V.; Graves, D.; Ames, S.; Krishnamani, P.P. Effect of a Virtual Reality-Enhanced Exercise and Education Intervention on Patient Engagement and Learning in Cardiac Rehabilitation: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e23882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, N.M.; Balogun, S.K.; Oratile, K.N. Managing stress: The influence of gender, age and emotion regulation on coping among university students in Botswana. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2014, 19, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabras, E.; Pozo, P.; Suárez-Falcón, J.C.; Caprara, M.; Contreras, A. Stress and academic achievement among distance university students in Spain during the COVID-19 pandemic: Age, perceived study time, and the mediating role of academic self-efficacy. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2024, 39, 4275–4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piumatti, G.; Garro, M.; Pipitone, L.; Di Vita, A.M.; Rabaglietti, E. North/South Differences Among Italian Emerging Adults Regarding Criteria Deemed Important for Adulthood and Life Satisfaction. Eur. J. Psychol. 2016, 12, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.J.; Mirabelli, J.F.; Kunze, A.J.; Romanchek, T.E.; Cross, K.J. Undergraduate student perceptions of stress and mental health in engineering culture. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2023, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calizaya-López, J.; Pinto-Pomareda, H.; Lazo-Manrique, M.C.; Bellido-Medina, R.; Vilca, A.R.M.; Ceballos-Bejarano, F. Comparison of Academic Stress in Students of Public and Private Universities in Peru. J. High. Educ. Theory Pract. 2022, 22, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khlaiwi, T.; Habib, S.S.; Akram, A.; Al-Khliwi, H.; Habib, S.M. Comparison of depression, anxiety, and stress between public and private university medical students. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2023, 12, 1092–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Cao, X. Bidirectional reduction effects of perceived stress and general self-efficacy among college students: A cross-lagged study. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madson, R.C.; Perrone, P.B.; Goldstein, S.E.; Lee, C.-Y.S. Self-Efficacy, Perceived Stress, and Individual Adjustment among College-Attending Emerging Adults. Youth 2022, 2, 668–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, C.; Ayala, A.; Trejo, L.A.; Ramos, B.; Briz, C.L.; Noriega, I.; Chávez, A. Measuring the Effectiveness of a Multicomponent Program to Manage Academic Stress through a Resilience to Stress Index. Sensors 2023, 23, 2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, C. Enhancing Mental Health, Well-Being and Active Lifestyles of University Students by Means of Physical Activity and Exercise Research Programs. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 849093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonato, L.C.; Prado, A.K.G.; dos Santos, D.L.; Tobar, K.D.L.; Araújo, J.A.; Ferreira, J.C.; Cambri, L.T. Acute Physical Exercise Reduces Mental Stress-Induced Responses in Teachers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.R.; Goicochea, S.; Merlo, L.J. In their own words: Stressors facing medical students in the millennial generation. Med. Educ. Online 2018, 23, 1530558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham Thi, T.D.; Duong, N.T. Investigating learning burnout and academic performance among management students: A longitudinal study in English courses. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisyah, D.; Hasanuddin, H.; Munir, A. Hubungan Kepribadian Tangguh dan Optimisme dengan Stres Akademik pada Siswa SMA Negeri 1 Binjai. J. Educ. Hum. Soc. Sci. (JEHSS) 2023, 5, 1894–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harahap, N.R.A.; Badrujaman, A.; Hidayat, D.R. Determinants of Academic Stress in Students. Bisma J. Couns. 2022, 6, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Roy, S.; Mandal, A. A Rough Set Based Approach to Compute Impact of Non Academic Parameters on Academic Performance. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Distributed Computing and Intelligent Technology, Bhubaneswar, India, 18–22 January 2023; pp. 316–327. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, V.N.; Wasnik, S.; Joshi, S.M.; Velankar, D.H. Medical students’ perceptions of stress factors affecting their academic performance, perceived stress and stress management techniques. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2018, 5, 1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Haegele, J.A.; Liu, H.; Yu, F. Academic Stress, Physical Activity, Sleep, and Mental Health among Chinese Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjet, C. Stress management interventions for college students in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 30, e12353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjala, K. Understanding the Academic Stress: Factors, Impact and Strategies: A Review. Int. J. Adv. Res. Innov. 2024, 12, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayathri, P.; Devi, M.N.; Balasubramaniam, P.; Duraisamy, M.R. Assessing the Strategies for Coping with Academic Stress among the Undergraduate Students of TNAU. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 2022, 40, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatunoglu, B.Y. Stress coping strategies of university students. Cypriot J. Educ. Sci. 2020, 15, 1320–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrai, F.; Magavern, E.F.; Micheluzzi, V.M.; Magnaghi, C.R.; Apuzzo, L.M.; Brioni, E.R. Effectiveness of Music to Improve Anxiety in Hemodialysis Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2020, 34, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sex | N | % |

| Male | 500 | 23.80% |

| Female | 1603 | 76.20% |

| Age | Mean | SD |

| 23.4 | 5.68 | |

| N | % | |

| Young (18–24 years) | 1608 | 76.46% |

| Young adults (25–39 years) | 431 | 20.45% |

| Middle age (40–62 years) | 65 | 3.09% |

| Religious Faith | N | % |

| Roman catholic | 1103 | 52.40% |

| Other religion | 137 | 6.50% |

| Atheist/Agnostic | 571 | 27.20% |

| Indifferent | 292 | 13.90% |

| Religious Practice | N | % |

| No | 1496 | 71.10% |

| Yes | 607 | 28.90% |

| Study Level | N | % |

| Bachelor’s degree | 1653 | 78.60% |

| Master’s degree | 450 | 21.40% |

| Course of Studies | N | % |

| Health science (Nursing, Medicine, Dentistry, Nutrition, Psychology) | 1477 | 70.20% |

| Science (Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry, Biology, Biotechnology, etc.) | 122 | 5.80% |

| Humanities (Philosophy, Literature, Communication, Law, Educational sciences, Economics, etc.) | 275 | 13.10% |

| Engineering | 175 | 8.30% |

| Other | 54 | 2.60% |

| Course Year | N | % |

| 1 | 488 | 23.20% |

| 2 | 881 | 41.90% |

| 3 | 396 | 18.80% |

| 4 | 120 | 5.70% |

| 5 | 147 | 7.00% |

| 6 | 71 | 3.40% |

| Geographical Area | N | % |

| North | 330 | 15.70% |

| Centre | 1157 | 55.00% |

| South | 156 | 7.40% |

| Main islands | 460 | 21.90% |

| Private University | N | % |

| No | 1717 | 81.60% |

| Yes | 386 | 18.40% |

| Offsite | N | % |

| No | 1145 | 64.18% |

| Yes | 638 | 35.76% |

| No answer | 320 | 17.94% |

| Scholarship/Place in the College of Merit | N | % |

| No | 1431 | 80.62% |

| Yes | 344 | 19.38% |

| No answer | 328 | 18.48% |

| Mean | SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upset because of something that happened unexpectedly | 1.61 | 1.09 | ||

| Unable to control the important things in your life | 1.68 | 1.10 | ||

| Nervous and “stressed” | 3.08 | 0.91 | ||

| Could not cope with all the things that you had to do | 2.47 | 1.05 | ||

| Angered because of things that were outside your control | 2.32 | 1.13 | ||

| Difficulties were piling up so that you could not overcome them | 1.73 | 1.20 | ||

| Confident about your ability to handle your personal problems | 1.59 | 0.96 | ||

| Things were going your way | 2.05 | 0.90 | ||

| Dealt successfully with irritating life hassles | 1.90 | 0.89 | ||

| You were on top of things | 2.11 | 0.97 | ||

| Pressured by the standards imposed by the institution | 2.84 | 1.11 | ||

| Strongly pressured by teachers regarding your performance | 1.69 | 1.29 | ||

| Competition with classmates about grades was very intense | 1.30 | 1.32 | ||

| Strongly pressured by your family about your grades | 1.18 | 1.31 | ||

| Your university experience caused you more stress than you could usually handle | 2.38 | 1.22 | ||

| STRESS | 12.90 | 4.86 | 2.15 ^ | 0.81 ^ |

| COPING | 7.64 | 2.90 | 1.91 ^ | 0.73 ^ |

| ACADEMIC STRESS | 9.41 | 4.46 | 1.88 ^ | 0.89 ^ |

| IPSS-R | 29.90 | 9.94 | 1.99 ^ | 0.66 ^ |

| Component | Eigenvalue | Percentage of Variance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Things were going your way | 4.905 | 40.87 |

| 2 | Your university experience caused you more stress than you could usually handle | 1.647 | 13.72 |

| 3 | Dealt successfully with irritating life hassles | 0.999 | 8.32 |

| 4 | You were on top of things | 0.678 | 5.65 |

| 5 | Pressured by the standards imposed by the institution | 0.612 | 5.10 |

| 6 | Confident about your ability to handle your personal problems | 0.581 | 4.84 |

| 7 | Nervous and “stressed” | 0.525 | 4.37 |

| 8 | Difficulties were piling up so that you could not overcome them | 0.489 | 4.08 |

| 9 | Could not cope with all the things that you had to do | 0.434 | 3.62 |

| 10 | Angered because of things that were outside your control | 0.415 | 3.46 |

| 11 | Strongly pressured by teachers regarding your performance | 0.367 | 3.06 |

| 12 | Upset because of something that happened unexpectedly | 0.348 | 2.90 |

| Component | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | Uniqueness | |

| You were on top of things | 0.754 | 0.419 | |

| Things were going your way | 0.744 | 0.435 | |

| Dealt successfully with irritating life hassles | 0.742 | 0.447 | |

| Confident about your ability to handle your personal problems | 0.712 | 0.474 | |

| Difficulties were piling up so that you could not overcome them | 0.561 | 0.539 | 0.395 |

| Upset because of something that happened unexpectedly | 0.433 | 0.422 | 0.634 |

| Pressured by the standards imposed by the institution | 0.815 | 0.334 | |

| Your university experience caused you more stress than you could usually handle | 0.769 | 0.372 | |

| Strongly pressured by teachers regarding your performance | 0.748 | 0.432 | |

| Nervous and “stressed” | 0.420 | 0.593 | 0.471 |

| Could not cope with all the things that you had to do | 0.456 | 0.543 | 0.498 |

| Angered because of things that were outside your control | 0.446 | 0.513 | 0.538 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Micheluzzi, V.; Sandri, E.; Marchetti, A.; De Benedictis, A.; Petrucci, G.; Alvaro, R.; De Marinis, M.G.; Piredda, M. Perceived Stress Profiles Among Italian University Students: A Multivariate Approach. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2830. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222830

Micheluzzi V, Sandri E, Marchetti A, De Benedictis A, Petrucci G, Alvaro R, De Marinis MG, Piredda M. Perceived Stress Profiles Among Italian University Students: A Multivariate Approach. Healthcare. 2025; 13(22):2830. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222830

Chicago/Turabian StyleMicheluzzi, Valentina, Elena Sandri, Anna Marchetti, Anna De Benedictis, Giorgia Petrucci, Rosaria Alvaro, Maria Grazia De Marinis, and Michela Piredda. 2025. "Perceived Stress Profiles Among Italian University Students: A Multivariate Approach" Healthcare 13, no. 22: 2830. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222830

APA StyleMicheluzzi, V., Sandri, E., Marchetti, A., De Benedictis, A., Petrucci, G., Alvaro, R., De Marinis, M. G., & Piredda, M. (2025). Perceived Stress Profiles Among Italian University Students: A Multivariate Approach. Healthcare, 13(22), 2830. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222830