1. Introduction

Pressure ulcers (PUs) are a significant challenge for health systems, extending beyond the immediate concerns of wound management, and include broader patient safety issues [

1]. PUs are injuries to the skin and underlying tissues that result from long mechanical loading and are more frequent in patients with limited mobility. The etiology of PUs includes patient factors, such as comorbidities, age-related tissue fragility, and nutritional deficiencies, as well as external factors, such as mechanical forces and hospital care environment characteristics [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. The occurrence of PUs is both a clinical concern and a quality-of-care indicator, emphasizing the responsibility of health providers to prevent injury and to mitigate adverse outcomes [

1,

8].

Intensive care units (ICUs), long-term care acute settings, and nursing homes have higher PU incidence rates, likely due to patient acuity, hospital care practices, and issues with staffing, lack of educational initiatives, or prevention protocols [

8,

9]. Older age is a significant risk factor because of age-related skin changes, tissue integrity, reduced mobility, and the higher prevalence of comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes [

2,

9]. Among younger populations, those mostly affected are patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation or extensive surgical interventions [

4,

9].

Prolonged pressure over bony prominences impairs tissue perfusion, leading to hypoxia, metabolic dysfunction, and, ultimately, cellular necrosis [

2]. This is the reason patients with conditions such as compromised cardiovascular function and diabetes are particularly vulnerable [

2,

3]. In addition, hospital environmental factors play a critical role. Patients in critical care settings experience extended immobility, sedation, and exposure to medical devices, such as mechanical ventilators, catheters, and vascular access devices, all of which can contribute to tissue damage and delayed healing [

4,

5,

6,

10]. Staffing adequacy, nursing education, and institutional culture also influence PU outcomes, with insufficient knowledge of prevention protocols or a lack of systematic risk assessment contributing to higher incidence rates [

7,

11].

Evidence-based strategies for PU prevention include evidence-driven risk assessment, targeted interventions, and continuous monitoring. Validated instruments, such as the Braden Scale and Norton Scale, are available to measure risk and facilitate early identification of high-risk patients and focus on preventive resources at specific anatomical sites [

12,

13]. Repositioning protocols and the use of pressure-relieving surfaces reduce mechanical loading and forces, lowering the likelihood of tissue injury [

14,

15,

16]. Positioning techniques (e.g., 30-degree lateral rotation method) can be particularly effective in reducing pressure over bony prominences [

16]. Malnutrition also increases susceptibility to PUs (affecting tissue repair and skin integrity), and this emphasizes the need for nutritional assessment as part of PU prevention programs [

17].

Health provider education has been shown to improve knowledge and attitudes about patient safety, which, in turn, contribute to safer clinical practices related to PU prevention [

11,

18]. Quality monitoring includes process measures (e.g., completion rates of risk assessments and preventive interventions) and outcome measures (e.g., PU incidence, stage, and severity) as well [

19,

20,

21].

The clinical consequences of PUs extend beyond local tissue injury, affecting patient quality of life, functional status, and mental health. Patients report pain, sleep disturbances, mobility limitations, anxiety, depression, and reduced self-efficacy [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. These impacts often influence long-term recovery and rehabilitation outcomes and extend beyond the hospital stay. Patients with advanced-stage PUs have a higher risk for infection, sepsis, and delayed recovery from underlying medical conditions, which have been associated with increased morbidity and mortality [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. In addition, multiple co-existing PUs create compound challenges, reflecting underlying vulnerability, nutritional compromise, and complex care needs, further straining healthcare resources [

2,

32,

33]. The psychological and social implications of multiple PUs, including body image, social withdrawal, and caregiver strain, emphasize the importance of patient-centered approaches that address physical and psychosocial dimensions of care [

26,

34].

PU staging provides a framework for assessing injury severity and includes four stages. While Stage I PUs can easily be managed [

30,

35], Stage II PUs require specialized wound care [

36]. Stages III and IV PUs, though, are associated with increased risk of infection, sepsis, and prolonged recovery [

31] and increase resource utilization [

24].

The anatomical site and multiplicity of PUs also influence clinical outcomes. The sacrum, heels, buttocks, hips, and elbows are the most affected regions, and multiple co-existing ulcers indicate compounded clinical challenges [

2,

32]. Multiple PUs are frequently linked with malnutrition, advanced frailty, limited healing capacity, increased risk for infection, prolonged hospitalization, and increased mortality risk [

2,

32,

33]. The psychological burden of multiple ulcers compounds patient vulnerability and interventions that address mental health alongside physical wound care [

26,

34].

While prevention strategies and risk assessment tools are well established, there remains a need to quantify the frequency, stage, and anatomical characteristics of PUs and evaluate their association with clinical outcomes. Mapping PU prevalence and PU characteristics can offer a useful tool to understand early risk detection, preventive interventions, and improved resource allocation. Moreover, understanding the relationship between PUs and adverse outcomes provides evidence to support quality improvement initiatives and patient safety policies. The present study aims to address this knowledge gap by (i) mapping the frequency, anatomical site, stage, and characteristics of PUs and (ii) examining their association with inpatient LOS and hospital mortality (all-cause) among hospitalized elderly patients. This study was not designed to explain the mechanism or clinical cause of comorbidities, but it focuses on their burden and the patterns of PUs that are associated with a higher burden for the two study outcomes. By combining descriptive analyses of PU patterns with outcome associations, this study aims to improve our understanding of PU burden in hospital settings. The findings could also guide prevention strategies, inform clinical risk stratification (and help healthcare providers prioritize high-risk patients), optimize care processes, and support evidence-based patient safety interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A retrospective cross-sectional study using secondary administrative data was designed to examine hospitalized Medicare patients with documented pressure ulcers. The first goal of this research was to create a mapping of the PUs, including their frequency, the most frequent combinations, and their stages. Goal 2 was to examine the association between PU site, stage, and multiple PU presence and two critical hospital outcomes: inpatient mortality and LOS. After the bivariate analysis was completed, this study furthermore controlled for demographics, primary Dx, and source of admission.

Figure 1 shows a diagrammatic representation of the study design.

2.2. Dataset and Study Variables

This study used a dataset of 1,123,121 Medicare beneficiary inpatient admissions. The CMS Limited Data Set (LDS) Inpatient dataset is a de-identified claims dataset that includes information on inpatient hospital stays for Medicare patients for the year 2019. The dataset includes every Medicare inpatient admission that happened in hospitals located in the United States during that year. The dataset is made available directly via CMS. The researchers did not extract the original data themselves. Instead, the extracted and cleaned data is made available directly through CMS. CMS itself compiles the dataset and releases it on an annual and quarterly basis. It contains data on patient demographics, diagnoses (ICD-10-CM codes), procedures, LOS, discharge status, hospital charges, and other administrative details. Although patient identifiers are removed, the dataset has important variables that enable health services and outcomes research at a national level in the United States.

Several derived variables were created from the dataset, as appropriate, to examine how the PU characteristics of (i) locality, (ii) stage, and (iii) multiple PU presence are associated with the hospital mortality and LOS. All admissions were reviewed for the presence of PUs using ICD-10-CM Dx codes. Each unique PU ICD-10-CM code was extracted and coded as a dichotomous variable (present/absent) for analysis. A total of 25 groups of ICD-10-CM PU codes were identified. These codes included anatomical site-specific designations (e.g., sacral, heel, back) and were further detailed using secondary billable ICD-10-CM codes that captured the stage of the PU, classified as Stage 1, Stage 2, Stage 3, Stage 4, or unstageable. A summary of all extracted codes, along with their frequency of occurrence in the dataset, is provided in

Table 1. The pressure ulcers were identified by scanning all ICD-10-CM medical diagnosis codes (primary and secondary) per patient, looking for codes representing pressure ulcers. PU codes were identified by the official CMS online tool (

https://icd10cmtool.cdc.gov/?fy=FY2024, accessed on 3 November 2025) by using the keyword “pressure ulcer”. The codes were validated by the pressure ulcer code list from icd10Data.com. A total of 149 pressure ulcer codes were identified, representing 25 different anatomical sites. There are different codes for left and right anatomical sites (e.g., left elbow vs. right elbow PUs are represented by different codes). PUs on patients who had a PU on both sites of the same location were treated as different PUs and not merged. We made this decision because of the different implications that opposite sites (left vs. right) may have, such as underlying clinical and functional factors, instead of just being a random occurrence.

For each site, there are multiple child codes, each representing the pressure ulcer staging information. Readmission information was not available since the unit of analysis of the dataset is the hospital admission, and the patient id information is not available. We did not exclude any of the pressure ulcer codes from the analysis since the classification was well defined and unambiguous.

Comorbidities were not included as covariates because they are often interrelated with both ulcer development and outcomes. This could have obscured these primary relationships. In other words, comorbidities may function as mediators rather than pure confounders reflecting patient frailty that lies on the pathway between pressure ulcer severity and mortality or length of stay. We did decide to control for patient principal diagnosis because its presence allows for the adjustment for the clinical context in which PUs occurred (i.e., distinguishing surgical from medical cases).

In addition to analyzing individual PU anatomical sites, composite constructs representing the presence of two or more co-existing PU anatomical sites during the same hospitalization were developed. These constructs were created by identifying admissions in which multiple distinct ICD-10-CM PU codes (indicating different anatomical sites) were documented simultaneously. Dichotomous variables were generated to indicate the presence of multisite PUs, allowing for comparisons between patients with single and multisite PUs.

Therefore, with these data transformations, it was possible for the present study to examine three different PU characteristics: (i) PU anatomical site, (ii) PU stage, and (iii) multisite PU presence (more than 1 PU site code).

This approach enabled the evaluation of the cumulative burden of PUs on inpatient outcomes. The presence of multiple PU anatomical sites was analyzed as an independent variable in the regression models assessing two key outcomes: hospital LOS and inpatient mortality. By including these multisite constructs, this study aimed to determine whether patients with multiple PU anatomical sites experienced worse clinical outcomes compared to those with ulcers at a single site, after adjusting for covariates, as shown in

Table 1, which presents all the variables that this study used from the CMS dataset, their operational definitions, and their role in this research.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Initial descriptive statistics were calculated, including the mean LOS, mortality rate, and distribution of PU stages and anatomical sites. To examine the relationship between PU characteristics and inpatient outcomes, multivariable regression analyses were conducted. Specifically, linear regression models were used to evaluate the association between PU anatomical site and hospital LOS. A logistic regression model was used to assess the association between PU anatomical site and inpatient mortality. All regression models controlled for potential confounders, including primary Dx, age group, sex, and admission transfer from another setting/SNF.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A two-tailed alpha level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

4. Discussion

This study analyzed 1.1 million Medicare inpatient admissions to map the characteristics of PUs and examine their association with LOS and inpatient mortality. The overall PU prevalence in this hospitalized Medicare population was 3.7%, which is consistent with national estimates. The most common anatomical sites were the sacral region, buttocks, and heels, likely due to immobility-related pressure. Stage 2 ulcers were the most frequently documented stage. However, a significant portion of ulcers, particularly on the heels and head, were classified as unstageable or unspecified.

PU severity, as measured by our Pressure Ulcer Locality–Stage score, was highest in the hips and contiguous back/buttock/hip sites and lowest in the heels and head. Unstageable or unspecified ulcers were most frequent in the hips, heels, ankles, and elbows. The bivariate analysis also highlighted the following sites with the highest mortality: left upper back (14.04%), head (12.82%), and unspecified hip (12.80%).

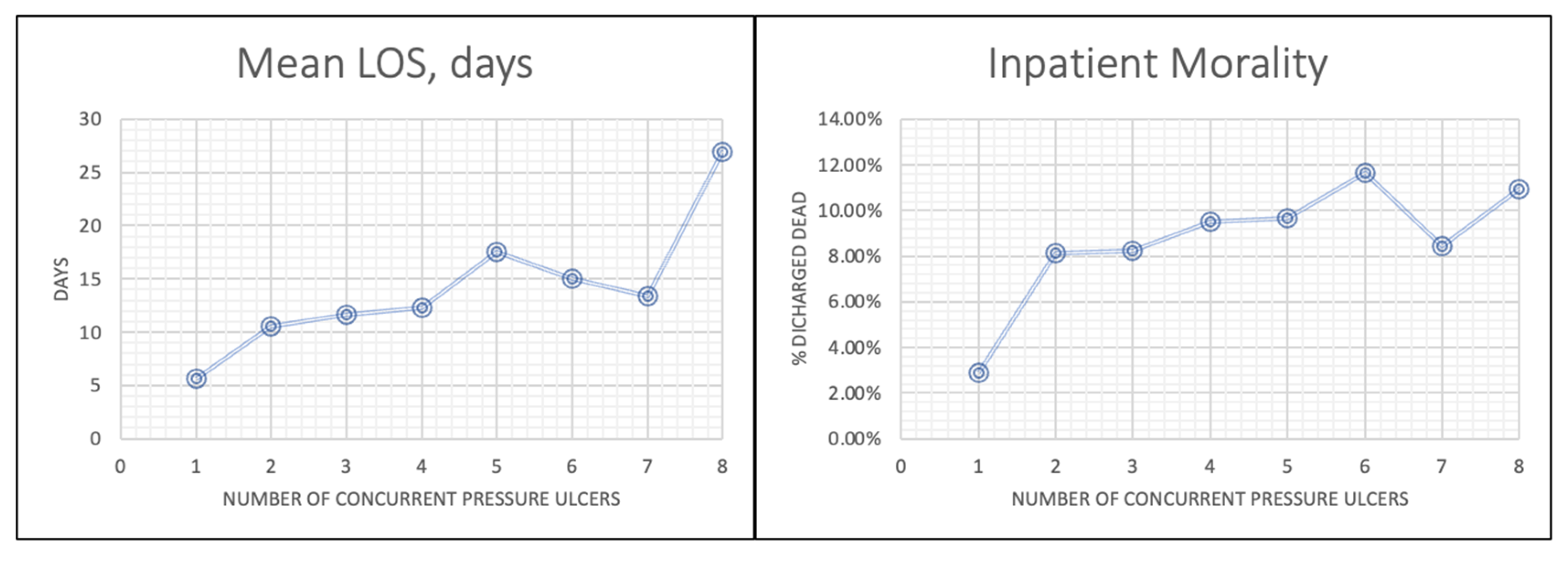

The central finding was that PU anatomical site and multiplicity were stronger predictors of LOS and mortality than PU stage alone. Multiple regression showed that PUs on the sacral region, hip, head, buttock, and upper back were risk factors for both prolonged LOS and increased inpatient mortality. LOS and mortality also increased progressively as the number of concurrent PUs rose. For example, patients with eight or more ulcers had a mean LOS of 23.5 days and a mortality rate of 12.5%, compared to 10.6 days and 8.1% for those with just one ulcer. Conversely, while LOS increased consistently with advancing stage (from 9.4 days for Stage 1 to 15.2 days for Stage 4), higher PU stage was not a significant predictor of inpatient mortality.

The finding that site and multiplicity are more predictive than stage suggests that PUs should be viewed not just as a localized skin injury, but as a proxy for systemic vulnerability. The specific high-risk sites are associated with immobility and are likely indicators of systemic frailty. The presence of multiple ulcers shows a compounding effect where healing capacity is compromised. The location and number of PUs, therefore, appear to carry more prognostic information about a patient’s overall health status than the depth of a single wound [

2].

We believe that the high frequency of Stage 2 ulcers is an issue of detection and subsequent documentation. Stage 1 PUs are often subtle or underreported in busy clinical settings. Stage 2, on the other hand, comes with a clear break in the skin, prompting easier (and likely more consistent) clinical recognition and coding.

It is concerning that the rate of “unstageable” or “unspecified” ulcers is very high, as this indicates issues in clinical assessment and documentation. For example, heel ulcers are often covered with eschar that prevents staging until debridement; head ulcers in elderly patients may present atypically. We would like to point out that unstageable ulcers themselves may hold clinical significance, as they could be proxies of overall patient vulnerability.

We will attempt to explain the lack of association between advanced PU stage and mortality. Firstly, patients with the most severe underlying illnesses may not survive long enough to develop advanced-stage (Stages 3 or 4) ulcers. Second, hospitals that are more diligent in documenting and coding higher-stage PUs may also be those with more robust prevention and care protocols, which, in turn, reduce the impact of an ulcer on mortality. Finally, as noted in our methods, comorbidities were treated as mediators rather than confounders and were not included in the regression models. This means the mortality risk is likely driven by the underlying illness severity rather than the ulcer itself.

The strong association between PUs and LOS represents a “feedback loop”. Prolonged hospitalization increases the risk of developing PUs; in turn, the presence of a PU, particularly an advanced-stage or multiple PUs, increases infection risk, therefore extending the hospital stay [

28].

The primary strength of this study is its large, national dataset, with high statistical power and generalizability to Medicare patients. However, we can identify some limitations. First, its reliance on ICD-10-CM codes from administrative data is subject to documentation and coding variability (i.e., a high number of “unstageable” ulcers). With the dataset, it is not possible to distinguish between pre-existing PUs and those acquired during hospitalization. We did use, though, the source of admission as a control variable to partly mitigate for this issue. We are aware that while this study identifies associations, it was not designed to establish causality.

Our findings have significant implications for clinical practice and patient safety. The evidence that anatomical site and multiplicity are stronger predictors of poor outcomes than stage alone can be the basis for rethinking risk assessment. Existing frameworks (such as the Braden and Norton Scales) should recognize specific PU locations and the presence of multiple ulcers as “red flag” indicators. This includes recognizing high-risk combinations, such as bilateral heels with sacral or hip involvement, which were associated with especially poor outcomes [

37].

The high prevalence of unstageable or unspecified pinpoints the need for improved documentation and administrative investment in staff education and training on staging frameworks. We strongly believe that accurate classification is required for appropriate treatment, enabling the early detection of high-risk patients.

Our findings should trigger discussions to improve bedside PU prevention and management. We also recognize the need for better allocation for support devices as well as specific protocols for patients with ulcers in high-risk locations (sacral, hip, head, upper back) or multiple PUs. In addition, this translates to prioritized skin assessments for these patients. Adjustments to treatment pathways should also be considered to initiate earlier wound care for PUs at high-risk sites [

38].

We believe that PUs should be viewed as both contributors and indicators of negative hospital outcomes. Prioritizing early detection, systematic prevention, and accurate documentation is critical to reducing both clinical harm to patients and the resource burden. Future research should focus on these high-risk PU patterns to understand specific patient subgroups and comorbidity constructs, which were beyond the scope of the present study. Future work should also examine organizational and structural hospital-level characteristics to understand how staffing, policies, technologies, ownership, or training gaps may contribute to the documentation inconsistencies that we found in this study.

5. Conclusions

The numerous unstageable ulcers, particularly in the heels and head, show ongoing challenges in documentation and staging accuracy. These findings suggest that training, resource availability, and assessment protocols can improve the classification and detection of PUs. PU site and multiplicity were stronger predictors of LOS and mortality than stage alone. The presence of multiple ulcers amplified these risks, supporting the interpretation that extensive ulceration signals a global decline in patient resilience.

A higher ulcer stage was not directly linked to increased mortality. This may be because of underlying illness severity or institutional coding and care practices that affect outcome patterns.

Overall, we believe that PUs should be viewed both as indicators and contributors to negative hospital outcomes. The feedback loop between prolonged LOS and PU severity shows the importance of early prevention, monitoring, and standardization in reporting. Validated risk assessments, pressure redistribution intervention, and staff education are foundational to controlling PU progression. Training should focus on early recognition of initial and hard-to-recognize skin changes. These preventive measures will also lessen the effects of PUs on hospital resource use and system-level outcomes.

While this study was not designed to examine associations between PUs and comorbidities, future research should also explore hospital-level determinants and patient-level comorbidities to better identify high-risk patient subgroups.