Evaluating the Impact of the Health Navigator Model on Housing Status Among People Experiencing Homelessness in Four European Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Outcomes

2.3. Statistical Analysis

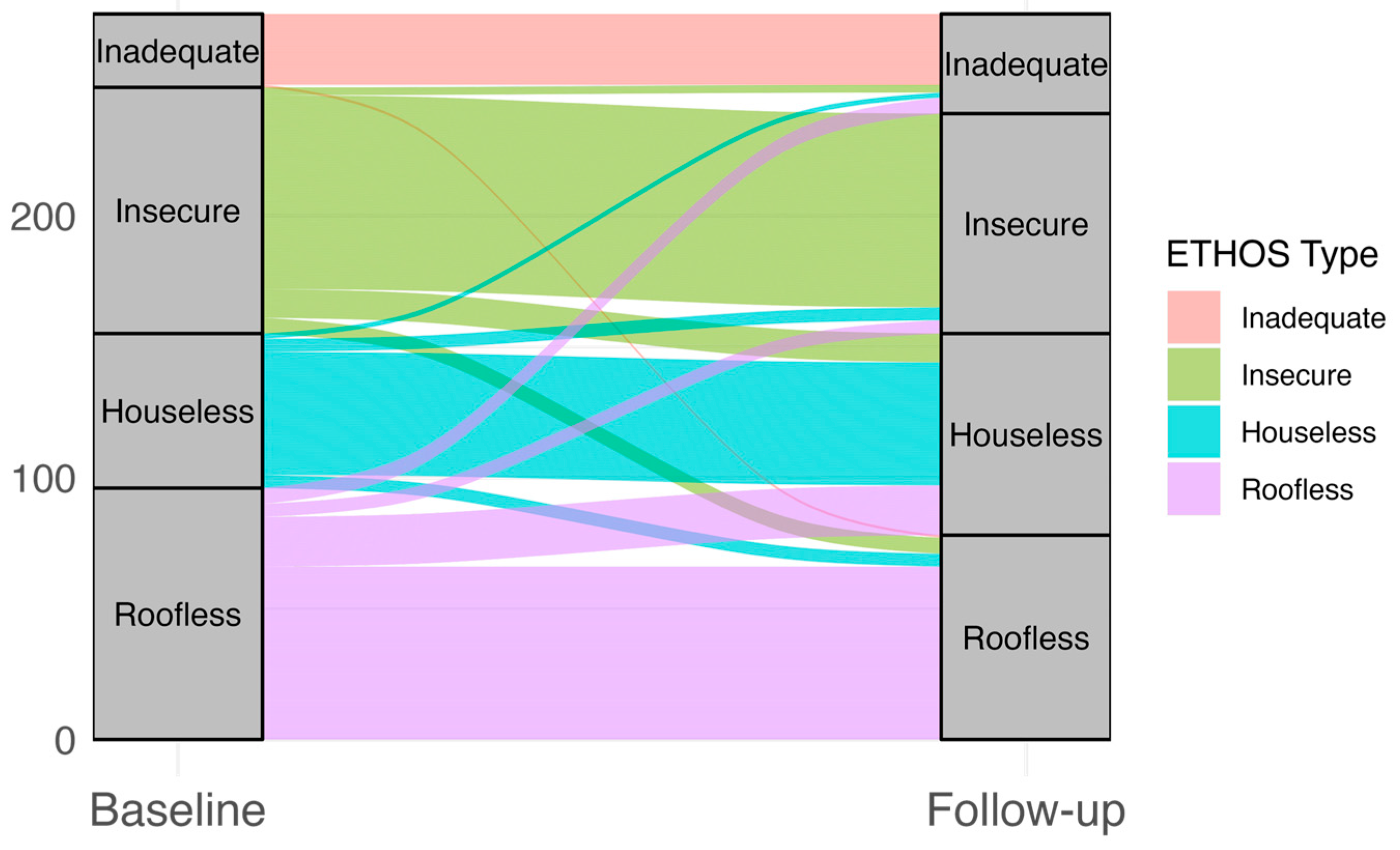

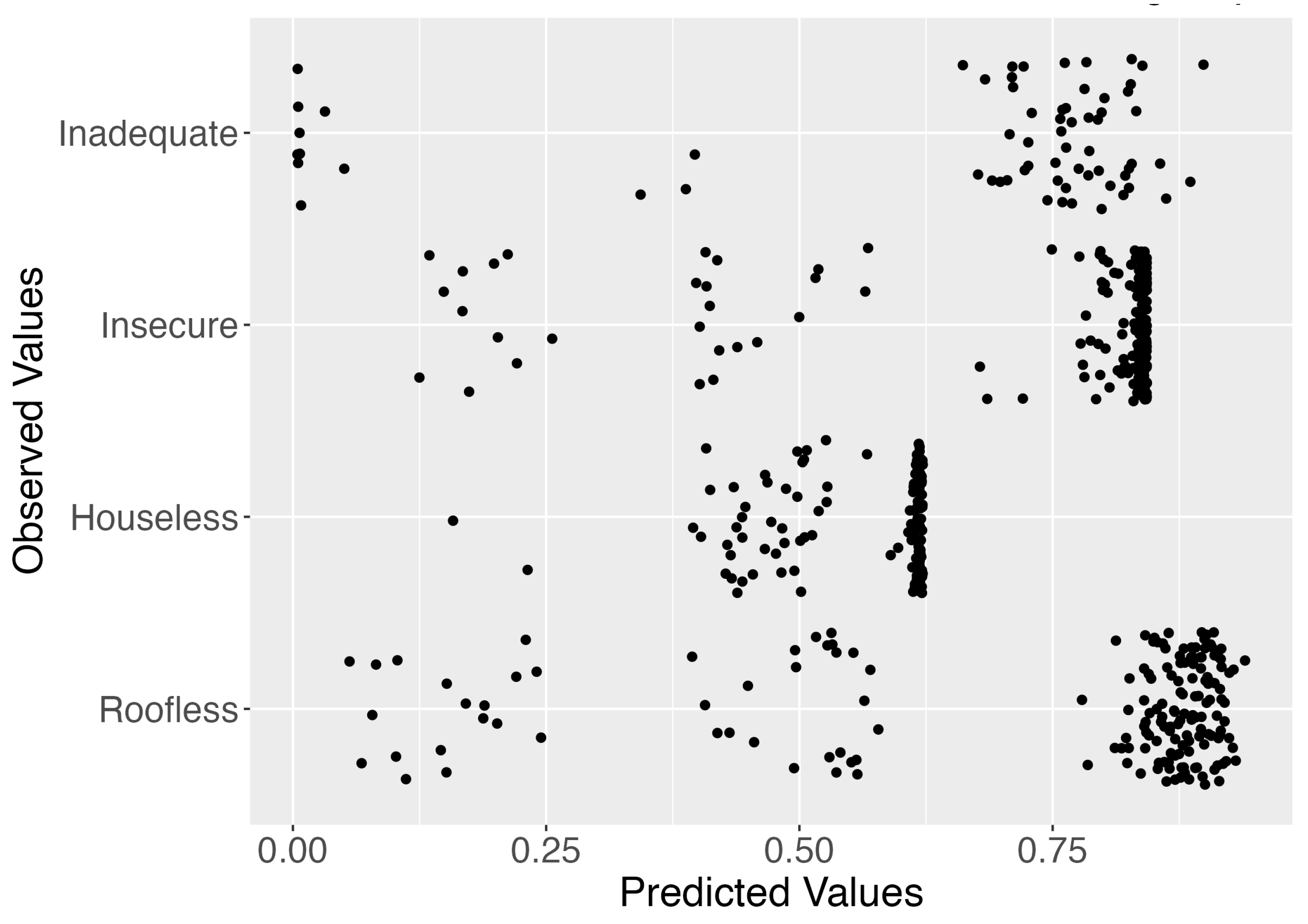

3. Results

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIC | Akaike information criterion |

| CLMM | Cumulative link mixed model |

| ETHOS | European Typology of Homelessness and Housing Exclusion |

| HNM | Health Navigator Model |

| PEH | People experiencing homelessness |

Appendix A

| Variable/Category | Completers (n = 277) | Dropouts (n = 375) |

|---|---|---|

| ETHOS Category (T0) | ||

| Roofless | 96 | 166 |

| Houseless | 59 | 118 |

| Insecure | 93 | 73 |

| Inadequate | 28 | 16 |

| NA | 1 | 2 |

| Education Level | ||

| Early childhood | 18 | 11 |

| Primary | 40 | 55 |

| Lower secondary | 75 | 107 |

| Upper secondary | 75 | 121 |

| Post-secondary non-tertiary | 22 | 23 |

| Short-cycle tertiary | 10 | 9 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 29 | 27 |

| Master’s degree | 1 | 4 |

| Doctoral degree | 0 | 0 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 171 | 247 |

| Female | 104 | 126 |

| Non-binary | 0 | 1 |

| Other | 1 | 1 |

| Prefer not to say | 1 | 0 |

| Smoking Status | ||

| Non-daily smoker | 113 | 119 |

| Daily Smoker | 164 | 255 |

| Alcohol Use | ||

| Never | 131 | 151 |

| Monthly or less | 57 | 60 |

| 2–4 times/month | 46 | 63 |

| 2–3 times/week | 23 | 46 |

| 4+ times/week | 20 | 46 |

| Psychoactive Substance Use | ||

| Never | 222 | 277 |

| Monthly or less | 9 | 21 |

| 2–4 times/month | 11 | 18 |

| 2–3 times/week | 8 | 15 |

| 4+ times/week | 24 | 33 |

| Meal Frequency | ||

| One | 48 | 50 |

| Two | 112 | 113 |

| Three | 97 | 166 |

| Four or more | 19 | 41 |

| None | 1 | 0 |

| Condom Use | ||

| Always | 56 | 56 |

| Most of the time | 39 | 25 |

| About half the time | 20 | 21 |

| Sometimes (<50%) | 16 | 23 |

| Rarely or never | 87 | 123 |

| Moderate Physical Activity | ||

| 10–30 min/day | 144 | 240 |

| 30–60 min/day | 22 | 60 |

| 1–2 h/day | 29 | 33 |

| 2–3 h/day | 4 | 6 |

| 3+ h/day | 6 | 6 |

| Vigorous Physical Activity | ||

| 10–30 min/day | 160 | 288 |

| 30–60 min/day | 10 | 31 |

| 1–2 h/day | 10 | 15 |

| 2–3 h/day | 2 | 0 |

| 3+ h/day | 2 | 2 |

| Handwashing | ||

| Never | 6 | 6 |

| Once | 28 | 77 |

| 2–4 times | 148 | 190 |

| 5 or more | 95 | 98 |

| Sun Exposure | ||

| Never | 22 | 20 |

| Rarely | 82 | 106 |

| Sometimes | 86 | 140 |

| Often | 84 | 103 |

| Birth Region | ||

| Asia | 8 | 3 |

| Eastern Europe | 42 | 53 |

| Latin America | 7 | 23 |

| Middle East/Central Asia | 10 | 8 |

| Missing | 1 | 2 |

| North Africa | 3 | 27 |

| Other | 11 | 25 |

| Southeast Asia | 8 | 0 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 8 | 23 |

| UK | 52 | 77 |

| USA | 2 | 0 |

| Western Europe | 125 | 134 |

References

- FEANTSA; Fondation Abbé Pierre. Ninth Overview of Housing Exclusion in Europe 2024. Available online: https://www.feantsa.org/public/user/Activities/events/2024/9th_overview/Rapport_-_EN.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Boesveldt, N.F. Denying homeless persons access to municipal support. Int. J. Hum. Rights Healthc. 2019, 12, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavan, R.; Barry, M.M.; Matanov, A.; Barros, H.; Gabor, E.; Greacen, T.; Holcnerová, P.; Kluge, U.; Nicaise, P.; Moskalewicz, J.; et al. Service provision and barriers to care for homeless people with mental health problems across 14 European capital cities. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, C.; Schiffler, T.; Smith, L.; Moudatsou, M.; Tabaki, I.; Doñate-Martínez, A.; Alhambra-Borrás, T.; Kouvari, M.; Karnaki, P.; Gil-Salmeron, A.; et al. Barriers and facilitators to health care access for people experiencing homelessness in four European countries: An exploratory qualitative study. Int. J. Equity Health 2023, 22, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omerov, P.; Craftman, Å.G.; Mattsson, E.; Klarare, A. Homeless persons’ experiences of health- and social care: A systematic integrative review. Health Soc. Care Community 2020, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cernadas, A.; Fernández, Á. Healthcare inequities and barriers to access for homeless individuals: A qualitative study in Barcelona (Spain). Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowen, E.; Savino, R.; Irish, A. Homelessness and Health Disparities: A Health Equity Lens. In Homelessness Prevention and Intervention in Social Work; Larkin, H., Aykanian, A., Streeter, C.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 57–83. ISBN 978-3-030-03726-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, E. Voices of the Homeless: An Emic Approach to the Experiences of Health Disparities Faced by People Who Are Homeless. Soc. Work Public Health 2016, 31, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhera, R.K.; Khatana, S.A.M.; Choi, E.; Jiang, G.; Shen, C.; Yeh, R.W.; Joynt Maddox, K.E. Disparities in Care and Mortality Among Homeless Adults Hospitalized for Cardiovascular Conditions. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, K.; Alayo, Q.A.; Sedarous, M.; Nwaiwu, O.; Okafor, P.N. Healthcare Disparities Among Homeless Patients Hospitalized With Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Propensity-Matched, State-Level Analysis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2023, 57, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgary, R. Cancer screening in the homeless population. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, e344–e350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggett, T.P.; Chang, Y.; Porneala, B.C.; Bharel, M.; Singer, D.E.; Rigotti, N.A. Disparities in Cancer Incidence, Stage, and Mortality at Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeleff, M.; Haider, S.; Schiffler, T.; Gil-Salmerón, A.; Yang, L.; Barreto Schuch, F.; Grabovac, I. Cancer risk factors and access to cancer prevention services for people experiencing homelessness. Lancet Public Health 2024, 9, e128–e146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgary, R. Cancer care and treatment during homelessness. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, e84–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffler, T.; Carmichael, C.; Smith, L.; Doñate-Martínez, A.; Alhambra-Borrás, T.; Varadé, M.R.; Barrio Cortes, J.; Kouvari, M.; Karnaki, P.; Moudatsou, M.; et al. Access to cancer preventive care and program considerations for people experiencing homelessness across four European countries: An exploratory qualitative study. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 62, 102095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CORDIS. Cancer Prevention and Early Detection Among the Homeless Population in Europe: Co-Adapting and Implementing the Health Navigator Model. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/965351 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Freeman, H.P.; Rodriguez, R.L. History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer 2011, 117, 3539–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Health Promotion Glossary. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/64546/WHO_HPR_HEP_98.1.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Marmot, M.; Allen, J.; Bell, R.; Bloomer, E.; Goldblatt, P. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet 2012, 380, 1011–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, J.C.; Givens, M.L.; Johnson, S.P.; Kindig, D.A. Keeping It Political and Powerful: Defining the Structural Determinants of Health. Milbank Q. 2024, 102, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Gallant, A.J.; Delahunty-Pike, A.; Langley, J.E.; Zsager, A.; Abaga, E.; Ziegler, C.; Karabanow, J.; Hwang, S.W.; Pinto, A.D. Addressing housing insecurity as a social determinant of health: A systematic review of interventions in healthcare settings. Soc. Sci. Med. 2025, 384, 118557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco-Calafat, A.; Blanes-Selva, V.; Doñate-Martínez, A.; Fragner, T.; Alhambra-Borrás, T.; Gawronska, J.; Moudatsou, M.; Tabaki, I.; Belogianni, K.; Karnaki, P.; et al. An AI-based microsimulation for predicting health outcomes among people experiencing homelessness. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2025, 273, 109112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco-Calafat, A.; Blanes-Selva, V.; Fragner, T.; Doñate-Martínez, A.; Alhambra-Borrás, T.; García-Gómez, J.M.; Grabovac, I.; Saez, C. Multi-source coherence analysis of the first European multi-centre cohort study for cancer prevention in people experiencing homelessness: A data quality study. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEANTSA. ETHOS—European Typology of Homelessness and Housing Exclusion. Available online: https://www.feantsa.org/download/ethos2484215748748239888.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Fazel, S.; Geddes, J.R.; Kushel, M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: Descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet 2014, 384, 1529–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M.; Allen, J.J. Social determinants of health equity. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104 (Suppl. S4), S517–S519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiscock, R.; Bauld, L.; Amos, A.; Fidler, J.A.; Munafò, M. Socioeconomic status and smoking: A review. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1248, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, R.H.B. R Package, version 2023.12-4.1; Ordinal—Regression Models for Ordinal Data; CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Buuren, S.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J. Stat. Soft. 2011, 45, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassuk, E.L.; Latta, R.E.; Sember, R.; Raja, S.; Richard, M. Universal Design for Underserved Populations: Person-Centered, Recovery-Oriented and Trauma Informed. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2017, 28, 896–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baggett, T.P.; O’Connell, J.J.; Singer, D.E.; Rigotti, N.A. The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: A national study. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 1326–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, K.M.; Battaglia, T.A.; Calhoun, E.; Darnell, J.S.; Dudley, D.J.; Fiscella, K.; Hare, M.L.; LaVerda, N.; Lee, J.-H.; Levine, P.; et al. Impact of patient navigation on timely cancer care: The Patient Navigation Research Program. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, dju115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natale-Pereira, A.; Enard, K.R.; Nevarez, L.; Jones, L.A. The role of patient navigators in eliminating health disparities. Cancer 2011, 117, 3543–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderwick, H.A.J.; Gottlieb, L.M.; Fichtenberg, C.M.; Adler, N.E. Social Prescribing in the U.S. and England: Emerging Interventions to Address Patients’ Social Needs. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 54, 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasquez, D.E.; Mecklai, K.; Plevyak, S.; Eappen, B.; Koh, K.A.; Martin, A.F. Health system-based housing navigation for patients experiencing homelessness: A new care coordination framework. Healthcare 2022, 10, 100608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.W.; Chambers, C.; Chiu, S.; Katic, M.; Kiss, A.; Redelmeier, D.A.; Levinson, W. A comprehensive assessment of health care utilization among homeless adults under a system of universal health insurance. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103 (Suppl. 2), S294–S301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, S.; Khosla, V.; Doll, H.; Geddes, J. The prevalence of mental disorders among the homeless in western countries: Systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLoS Med. 2008, 5, e225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, K.F.; Grimes, D.A. Case-control studies: Research in reverse. Lancet 2002, 359, 431–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Completers Baseline | Dropouts Baseline | Completers Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | |||

| N | 277 | 375 | 277 |

| Gender: Male (%) | 61.7 | 65.9 | |

| Gender: Female (%) | 37.5 | 33.6 | |

| Age Mean (SD) | 49.4 (13.3) | 45.9 (14.0) | -- |

| Age Median (IQR) | 50 (20) | 47 (19) | -- |

| EU Citizen (Western Europe/UK) (%) | 63.9 | 56.3 | -- |

| Education Level | |||

| Lower Secondary (%) | 27.1 | 28.5 | |

| Upper Secondary (%) | 27.1 | 32.3 | |

| Health Risk Patterns | |||

| Daily Smoker (%) | 59.2 | 68.0 | 57.0 |

| Alcohol Use: Never (%) | 47.3 | 40.3 | 50.5 |

| Alcohol Use: Monthly or less (%) | 20.6 | 16.0 | 18.0 |

| Psychoactive Substance Use: Never (%) | 80.1 | 73.9 | 81.2 |

| Meal Frequency: Two/day (%) | 40.4 | 30.1 | 45.8 |

| Meal Frequency: Three/day (%) | 35.0 | 44.3 | 29.6 |

| Condom Use: Rarely or Never (%) | 31.4 | 32.8 | 33.2 |

| Moderate Physical Activity, i.e. 10–30 min/day (%) | 52.0 | 64.0 | 59.2 |

| Vigorous Physical Activity, i.e. 10–30 min/day (%) | 57.8 | 76.8 | 70.8 |

| Handwashing: 2–4 times/day (%) | 53.4 | 50.7 | 49.1 |

| Handwashing: 5+ times/day (%) | 34.3 | 26.1 | 35.0 |

| Sun Exposure: Sometimes (%) | 31.0 | 37.3 | 31.8 |

| Sun Exposure: Often (%) | 30.3 | 27.5 | 27.4 |

| ETHOS Subgroup Categories | |||

| Roofless n (%) | 96 (34.7) | 166 (44.3) | 78 (28.2) |

| Houseless n (%) | 59 (21.3) | 118 (31.5) | 77 (27.8) |

| Insecure n (%) | 93 (33.6) | 73 (19.5) | 84 (30.3) |

| Inadequate n (%) | 28 (10.1) | 16 (4.3) | 38 (13.7) |

| NA n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.5) | -- |

| Predictor | Odds Ratio | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time post (intervention) | 1.49 | 1.02 | 2.20 | 0.0418 | Significant positive time association (follow-up vs. baseline) |

| Age at baseline | 1.04 | 1.00 | 1.08 | 0.0649 | Not significant; slightly higher odds |

| Residence status at baseline (Asylum seeker) | 0.40 | 0.08 | 2.11 | 0.2801 | Not significant; possible lower odds |

| Residence status at baseline (Refugee) | 0.46 | 0.01 | 26.64 | 0.7062 | Not significant; very wide 95% CI |

| Residence status at baseline (Economic migrant in an irregular situation) | 24.13 | 6.41 | 90.89 | 2.53 × 10−6 | Strong, significant positive association |

| Daily smoking status | 0.33 | 0.11 | 0.96 | 0.0412 | Significant negative association |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guzman-Benitez, J.E.; Fragner, T.; Alhambra-Borrás, T.; Doñate-Martínez, A.; Blanes-Selva, V.; García-Gómez, J.M.; Barbu, S.; Gawronska, J.; Moudatsou, M.; Tabaki, I.; et al. Evaluating the Impact of the Health Navigator Model on Housing Status Among People Experiencing Homelessness in Four European Countries. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2805. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212805

Guzman-Benitez JE, Fragner T, Alhambra-Borrás T, Doñate-Martínez A, Blanes-Selva V, García-Gómez JM, Barbu S, Gawronska J, Moudatsou M, Tabaki I, et al. Evaluating the Impact of the Health Navigator Model on Housing Status Among People Experiencing Homelessness in Four European Countries. Healthcare. 2025; 13(21):2805. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212805

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuzman-Benitez, Juan Esteban, Tobias Fragner, Tamara Alhambra-Borrás, Ascensión Doñate-Martínez, Vicent Blanes-Selva, Juan M. García-Gómez, Simona Barbu, Julia Gawronska, Maria Moudatsou, Ioanna Tabaki, and et al. 2025. "Evaluating the Impact of the Health Navigator Model on Housing Status Among People Experiencing Homelessness in Four European Countries" Healthcare 13, no. 21: 2805. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212805

APA StyleGuzman-Benitez, J. E., Fragner, T., Alhambra-Borrás, T., Doñate-Martínez, A., Blanes-Selva, V., García-Gómez, J. M., Barbu, S., Gawronska, J., Moudatsou, M., Tabaki, I., Belogianni, K., Karnaki, P., Varadé, M. R., Gómez-Trenado, R., Barrio-Cortes, J., Smith, L., Gil-Salmerón, A., & Grabovac, I. (2025). Evaluating the Impact of the Health Navigator Model on Housing Status Among People Experiencing Homelessness in Four European Countries. Healthcare, 13(21), 2805. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212805