Abstract

Background/Objectives: Eco-anxiety is emerging as a response to worsening environmental conditions. However, several gaps hinder the estimation of this phenomenon worldwide. This review aims to provide a measure of eco-anxiety control by those factors that may affect its prevalence assessment. Methods: The review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines, and the protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42024556132). PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and PsycINFO databases were interrogated. Cross-sectional studies in English and Italian languages assessing eco-anxiety through validated questionnaires were considered. The quality assessment was conducted using the adapted Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale. Results: Sixty-nine articles published between 2020 and 2025 were included. Of these, 60 studies were meta-analyzed, for a total sample size exceeding 65,000 participants across different countries and cultural contexts. The overall pooled mean eco-anxiety level was approximately 34.8/100 (95% CI: 29.6–39.9), corresponding to a moderate level of eco-anxiety, with women scoring higher than men (p < 0.05). Assessment tool and country were also shown as significant predictors of eco-anxiety, while age did not seem to play a significant role. Conclusions: Though further rigorous research is needed in this field, focusing on these variables could help to design targeted strategies that address environmental concerns and support mental well-being and resilience towards environmental challenges.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, the increased frequency of phenomena related with global warming, such as heatwaves, rising sea levels, hurricanes and floods, have raised the general consciousness about the environmental, social and health consequences of climate change. Nowadays, there is increasing awareness that climate change is one of the most significant issues for human and planetary health [1,2,3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies climate change as the greatest threat to both physical and mental health [4]. In fact, besides physical disease and displacement, it can generate a sense of uncertainty and fear about the future, which may contribute to determining anxiety, stress, and other mental health issues [5].

In this scenario, a new psychological phenomenon, so-called “eco-anxiety”, is now emerging. Due to the complex and multifaceted nature of this phenomenon as a psychological response to the ongoing environmental crisis, there is no one universally accepted definition of eco-anxiety. Terms such as Climate Change Anxiety (CCA), climate-related worry, environmental distress, ecological grief, and ecological stress frequently appear in the literature, leading to a range of interpretations and definitions. For instance, eco-anxiety has been described as “extreme worry about current and future harm to the environment caused by climate change” [6] and as “a chronic fear of environmental doom” [7,8]. Additionally, it is characterized as “heightened emotional, mental, or somatic distress in response to dangerous changes in the climate system” [9,10]. Steffen et al. [11] defined eco-anxiety as a form of chronic fear or worry about the environmental catastrophe or “the generalized sense that the ecological foundations of existence are in the process of collapse” [12]. In 2011, Albrecht outlined this phenomenon by defining the “psychoterratic” syndromes as mental health impacts of negative emotions triggered by perceived environmental factors and climate change [13]. In general, eco-anxiety describes a complex emotional state characterized by worry, fear, helplessness, and sometimes even despair about the health of the planet and its long-term consequences for life; it can also include functional impairment and rumination [14]. It represents a new dimension of the interaction between the environment and the human psyche. With the growth in global climate crises, eco-anxiety has become the object of increasing attention within the scientific and psychological communities [15]. Preliminary findings have indicated that climate change may contribute to mental health issues, including functional impairment, symptoms of depression, anxiety, stress, and insomnia [16,17] and, in some cases, it could be a part of a broader syndrome, characterized by constant worries and intrusive thoughts [18]. On the other hand, some authors consider the anxiety related to climate change as a normal response and, for certain individuals, a motivation to environmentally sustainable behaviors [12]. In a world where climate change, natural disasters, and their consequences appear increasingly unavoidable, it is essential to understand how this threat affects the human mind and how the psychological effects of environmental crisis can be mitigated. Therefore, identifying eco-anxiety and its correlates in different populations can be useful to counteract them. Several scales have been developed over the years to assess eco-anxiety and its dimensions [16,19,20,21,22]. However, although their interrelation has been sometimes shown, the available scales differ in focus and domains. For example, some of these tools are aimed at assessing “eco-anxiety”, meant as feeling anxious about ecological problems, while others focus on “climate anxiety”, intended as feeling anxious about the climate crisis [21]. Furthermore, some studies in this field are aimed at assessing functional impairment or negative emotions such as worry towards ecological problems, which are related but do not coincide with eco-anxiety; some others explore eco-anxiety by using not validated tools or adapted questions nested in other questionnaires [10,14]. Other Authors have tried to describe the phenomenon of eco-anxiety, exploring the available literature, but they had to deal with these issues [10,14,21]. In this confusing context, the approach offered by a narrative synthesis, and even by a systematic review, cannot be sufficient from an epidemiological perspective.

Therefore, the present review aims to quantify the eco-anxiety worldwide by using a more inclusive search and a meta-analytic approach. We systematically analyze the available literature in this field, considering only those studies that assessed eco-anxiety through validated tools to shed light on the dimensions of eco-anxiety in the general population and on those factors that may affect its prevalence. Then, we proceeded to a meta-regression of the results by considering these factors as possible predictors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

This systematic review was carried out following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2) [23]. The review protocol was registered in PROSPERO with the reference number CRD42024556132. The review question focuses on eco-anxiety in the general population worldwide, in order to assess the presence of eco-anxiety in the general population and its possible differences among population groups.

The selection procedure was based on the “PICOS” Framework, as reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

“PICOS” Framework used for the study selection procedures.

Four electronic databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and PsycINFO) were then scrutinized using the following search string to find as many relevant articles as possible: “eco-anxiety” OR (“eco” AND “anxiety”) OR “climate anxiety” OR “climate worry” OR “solastalgia” OR “environmental distress” OR “eco distress” OR “eco-paralysis”. All databases were searched by title, abstract, and MeSH terms and keywords.

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Articles were deemed eligible if they reported the eco-anxiety level resulting from cross-sectional studies performed on the general population. Other types of studies, such as reviews, meta-analyses, case studies, qualitative investigations, book chapters, editorials, and commentary studies, were not considered. When pertinent, these other types of publications were examined to identify further articles in their references. We included items published in English and Italian, from the beginning of each database until 28 August 2025. Studies including the assessment of different fields other than eco-anxiety or assessing eco-anxiety through non-validated tools were excluded. For population and comparison, no exclusion criteria were adopted.

2.3. Study Selection

The titles and abstracts obtained from the three databases were imported into the reference management software Zotero (version 6.0.37), which was used for the initial assessment of relevance. Subsequently, the next phase involved a title and abstract screening, where potentially suitable studies were independently reviewed by three authors (A.D.G., E.M., and F.Gr.). Following this, the full texts of these studies were independently examined by the same authors, and a subsequent discussion took place regarding their potential inclusion in the review. Any disagreements were resolved through consensus among the authors. All the steps were supervised by three other investigators (C.P., F.Ga., and F.V.).

2.4. Data Extraction

The collected data were organized into a table that presented bibliographic details (including author, year of publication, country), sample size, study participant/population with age and gender, together with the scale or questionnaire used to assess eco-anxiety, eco-anxiety level values, and significantly correlated variables when reported.

2.5. Study Quality and Evaluation

The quality assessment of the selected articles was conducted using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale, adapted from cohort and case–control studies to perform a quality assessment for cross-sectional studies, as previously described [24]. The quality of each study was individually scored by three authors (A.D.G., E.M., and F.Gr.), and any discrepancies were resolved through consensus among all the authors. The ultimate rating for each article was calculated as the average of the three authors’ scores.

2.6. Data Synthesis and Meta-Analysis

Only studies assessing eco-anxiety with validated and standardized instruments were considered for the quantitative synthesis. In particular, eligible tools included the Climate Anxiety Scale (CAS) and its validated derivatives (e.g., Climate Change Anxiety Scale—CCAS, Climate Change Anxiety Scale for Women’s Health—CCASWH, and other local adaptations), the Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale (HEAS), and the Eco-Anxiety Questionnaire (EAQ). The first is a 13-item scale developed by Clayton and Karazsia in the United States, which considers two factors of the climate anxiety response: the cognitive-emotional impairments (such as difficulties concentrating and sleeping) and the functional impairments (such as difficulties socializing, working and studying) [16]. The HEAS, originally developed by Hogg et al. in Australia and New Zealand, is a 13-item questionnaire that looks for affective (e.g., feeling anxious), ruminative (e.g., persistent thoughts), and behavioural (e.g., difficulties working) symptoms of eco-anxiety and anxiety about the individual’s personal impact on the planet [21]. The EAQ, developed by Àgoston et al. in 2022, evaluates through 22 questions habitual ecological worry and the negative consequences of eco-anxiety [19]. When multiple studies from the same research group examined the same population cohort, only one of them was included in the meta-analysis, though the others were retained in the general overview.

For each study included in the meta-analysis, we extracted the following data: author, year, country, sample size (N), instrument, mean and standard deviation (SD) of eco-anxiety level. When only total scores were reported, values were normalized per item by dividing both mean and SD by the number of items (k), according to the original validation papers (CAS/CCAS/CCASWH/EMEA/HEAS = 13; EAQ = 22). This procedure enabled comparability across studies on their original Likert response range (e.g., 1–5 or 0–3).

When descriptive statistics were incomplete (e.g., data reported only as prevalence categories, ranges, or medians), we reconstructed mean and SD using established statistical methods for meta-analysis [25,26]. Studies for which no reliable reconstruction was feasible were excluded from quantitative pooling. To account for the heterogeneity of scoring ranges across instruments, we harmonized the data through transformation to a Percentage of Maximum Possible (POMP) scale [27]: POMP = [(Observed score − Minimum possible)/(Maximum possible − Minimum possible) × 100. This conversion standardizes scores to a 0–100 metric, interpretable as the percentage of the maximum possible eco-anxiety. Both means and SDs were transformed accordingly prior to pooling. Meta-analyses were performed in Jamovi (v. 2.5, MAJOR module), using raw means as effect size and applying random-effects models (DerSimonian–Laird and REML estimators, for meta-regression). Heterogeneity was evaluated with Cochran’s Q and I2 statistics, and 95% prediction intervals were calculated. Subgroup analyses were conducted by instrument type, while for the POMP dataset, a meta-regression including “instrument” as a moderator was carried out. Forest plots were generated with squares proportional to the inverse-variance weight of each study and horizontal lines indicating 95% confidence intervals.

3. Results

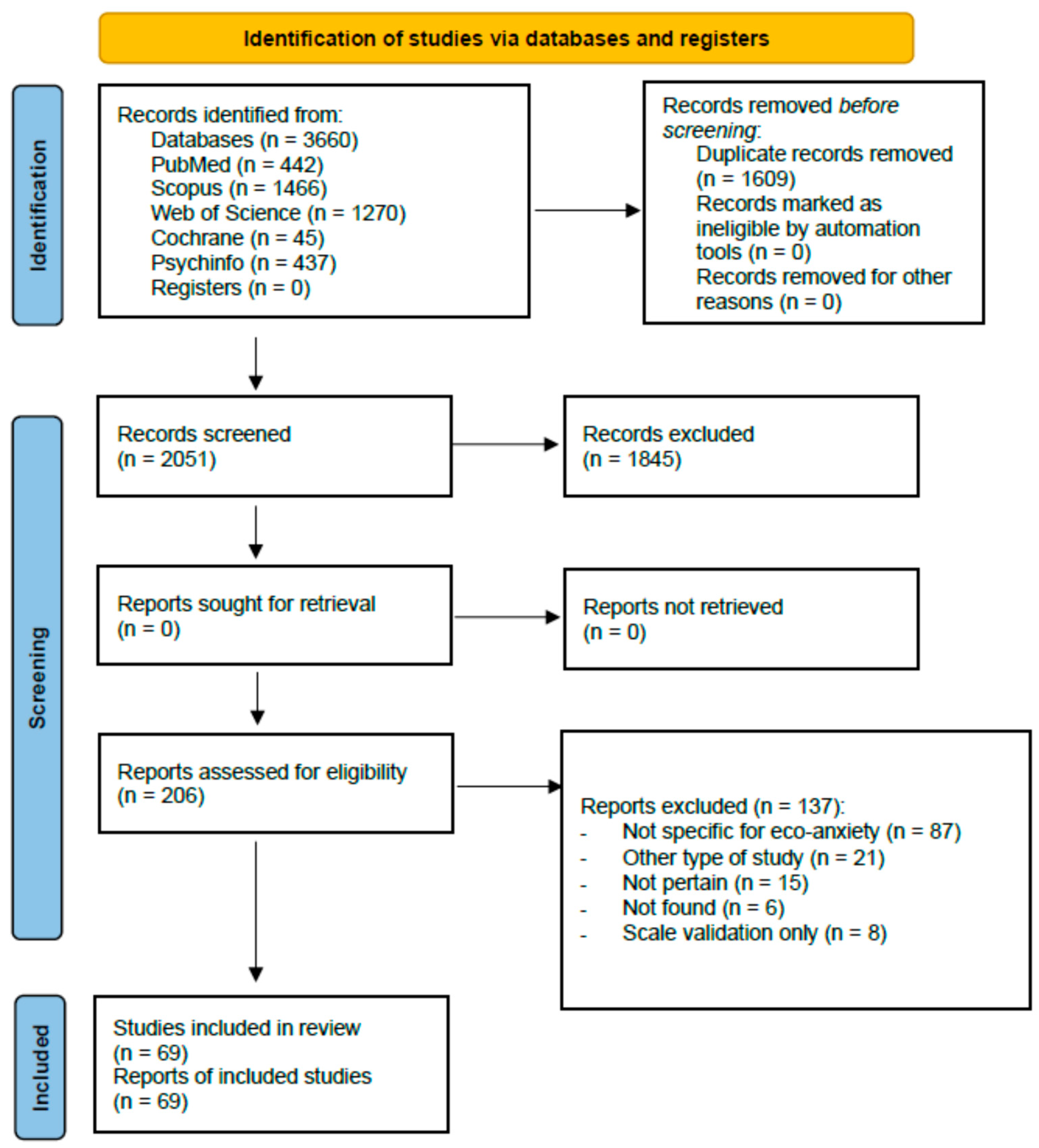

On a total of 3660 articles found, 69 were considered eligible (Figure 1) [16,21,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of the review process.

Table 2 reports the main characteristics of the included studies.

Table 2.

Main characteristics of the included studies.

The quality assessment with the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) indicated that most studies scored in the fair-to-good range (5–8/10), while only seven [34,49,60,61,84,88,91] were rated as poor (≤4/10). The detailed quality evaluation is reported in Supplementary Table S3. High-quality studies typically combined large and representative samples with robust ascertainment and reporting, whereas lower-quality articles were mainly limited by small sample sizes, convenience recruitment, or incomplete reporting.

Articles were published between 2020 and 2025 and reported cross-sectional findings from diverse contexts. European contributions came from 38 studies [32,34,38,39,40,41,42,44,45,46,47,48,51,52,53,54,55,57,62,64,65,66,67,68,74,76,77,78,80,82,84,88,89,90,91,92,93]. Oceania was represented in 6 studies [21,33,49,50,59,72]. Americas’ populations were examined in four studies [16,61,69,70]. Asian countries were analyzed in 15 studies [31,35,36,37,43,56,58,60,71,73,79,83,85,86,94]. In Africa, eco-anxiety was assessed in three studies [28,29,30]. There were three studies involving countries from more than one continent [63,81,87].

Sample sizes varied widely—from small convenience samples (40 participants) [88] to large multi-country surveys (4000 individuals) [87]. Both males and females were represented, often with a female majority; age groups ranged from adolescents to older adults, with many studies focusing on young adults. As expected, measures of eco-/climate anxiety varied across the studies. The mainly used tools to assess eco-anxiety were the Climate Anxiety Scale (CAS; Clayton & Karazsia) [16,21,28,29,30,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,52,53,55,56,57,60,61,65,68,70,77,78,79,83,85,87,89,91,92,93], and the Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale (HEAS) [21,31,36,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,58,59,61,62,64,67,69,71,72,73,75,76,80,81,82,84,86,88,90,94] in their different versions.

Research on eco-anxiety has expanded across regions, showing both shared patterns and context-specific nuances. In Europe, several studies linked climate anxiety to loneliness, mental health, perceived longevity, field of study and trust in science [32,38,39,40,41,42,46,47,80], while others reported correlations with affect and resilience [32,34,52,53,57,58,60,71,74,75,76,78,82,87,88] or with depression and life satisfaction [62,64]. Beyond Europe, African studies connected anxiety to environmental literacy or residence characteristics [28,30]. Turkey contributed one of the richest datasets, including validation work and studies on identity, health, and diet [35,36,37,43,71,73,86,94]. In North America, Canadian and U.S. studies showed that eco-anxiety is linked to existential meaning, affect and media exposure [16,61,69,70]. Australia and New Zealand were central in instrument development and characterization of the correlations with anxiety, depression and stress [21,33,49,50,59,72].

After transforming scores to the Percentage of Maximum Possible (POMP), standardized mean values ranged from a minimum of 1/100 [29] to a maximum of 82.5/100 [43] across the included studies (Table S4). Most estimates, however, clustered around the moderate range (40–50/100), indicating that while some populations reported very low or very high levels of eco-anxiety, the overall distribution suggested a central tendency toward moderate intensity [28,30,32,34,43,46,47,48,53,54,55,56,57,61,62,63,66,70,76,77,78,80,82,85,87,88]. Consistently, the random-effects pooled mean was ~34/100 (95% CI: 29–40). The broad confidence intervals for several studies further suggest considerable between-study heterogeneity.

As for the variables analyzed with eco-anxiety, gender differences are reported in 25 studies [16,21,28,31,36,43,44,50,54,55,57,58,64,65,67,73,74,80,81,84,86,87,88,93], with women showing quite always higher eco-anxiety or eco-anxiety subdomains than males. Age was the second most frequently studied variable, with 19 articles reporting higher levels of eco-anxiety in some age group, most frequently in the youngest [16,38,39,40,41,42,44,55,57,64,65,67,74,80,81,84,87,92]. Furthermore, the selected studies reported a wide variety of other variables correlated with eco-anxiety, such as psychological traits, place of residence, and engagement in pro-environmental behaviors, whose definition was very different across the studies and did not allow a comparison.

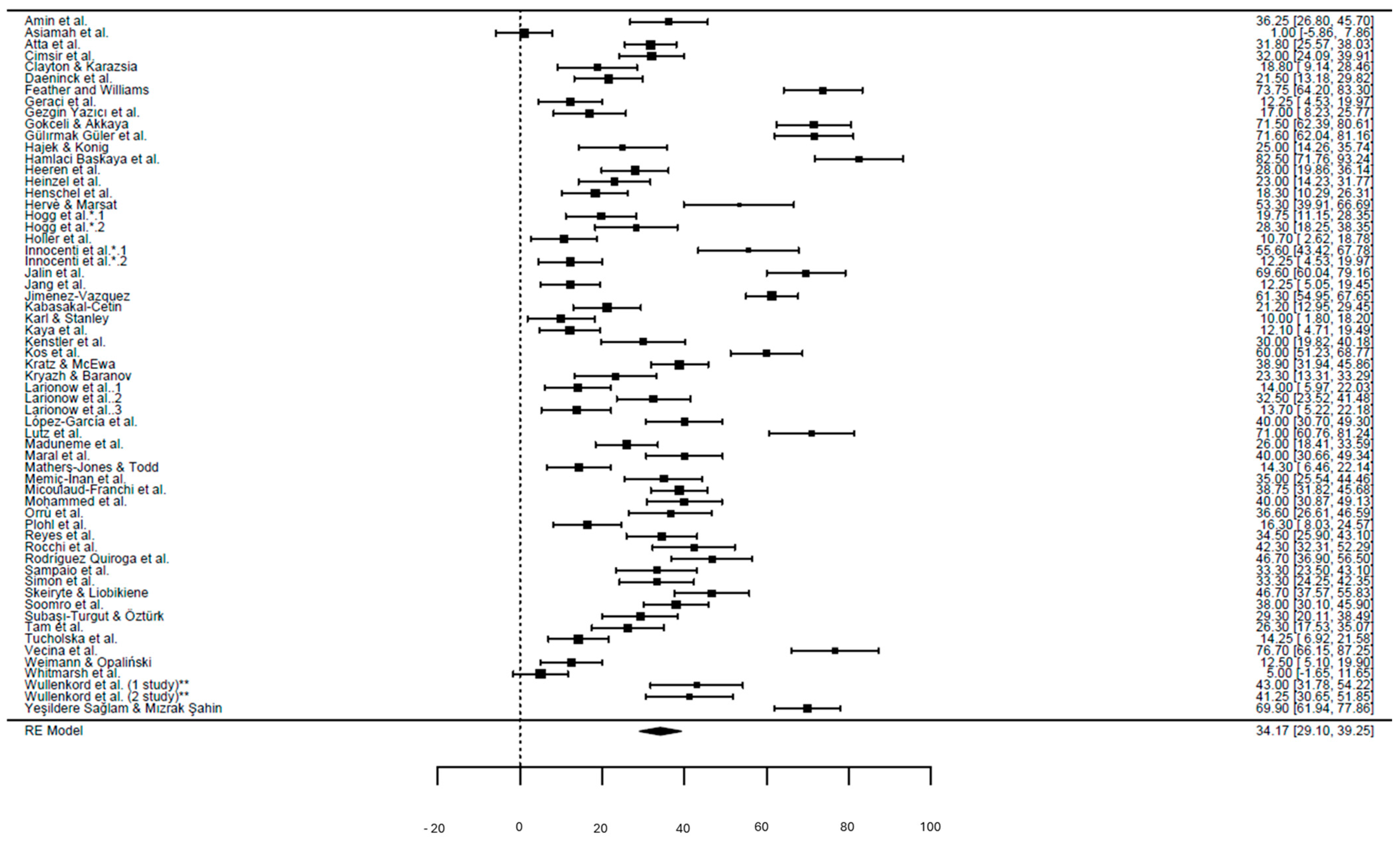

Therefore, we performed the meta-analysis including only the 60 studies [16,21,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,43,44,46,47,48,49,51,52,53,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,89,90,91,92,93,94] that assessed eco-anxiety using validated and standardized instruments (CAS, CCAS and derivatives, HEAS, EAQ), for a total sample size exceeding 65,000 participants across different countries and cultural contexts (Table S4). After transforming all scores to the Percentage of Maximum Possible (POMP) to harmonize scales with different ranges, the overall pooled mean eco-anxiety level was approximately 34.2/100 (95% CI: 29.1–39.2), corresponding to a moderate level of eco-anxiety. Between-study heterogeneity was very high (I2 > 95.6%), reflecting differences in instruments, populations, and study settings (Figure 2). The prediction interval was 13–55/100, indicating that future similar studies may observe eco-anxiety levels ranging from very low to moderately high. Subgroup analysis showed that eco-anxiety scores varied depending on the instrument used. Studies employing the CAS or its derivatives (n = 34) consistently reported mean values of about 40/100 (95% CI: 36–44), representing the majority of available data. The HEAS (n = 26) tended to produce slightly higher estimates, averaging 46/100 (95% CI: 41–52), with a stronger emphasis on affective and behavioral components. The EAQ (n = 2) yielded the highest values at approximately 51/100 (95% CI: 47–55). These differences were statistically significant, indicating that the choice of measurement tool explained part of the heterogeneity observed across studies.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis (k = 60 studies). Horizontal bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals of individual effect sizes, while the diamond at the bottom represents the pooled estimate (random-effects model, τ2 = 388.35, I2 = 95.3%; p < 0.001). * Analyses derived from the same cohorts using different scales (CAS and HEAS); ** Studies reporting two distinct study designs [16,21,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,43,44,46,47,48,49,51,52,53,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,89,90,91,92,93,94].

Meta-regression analyses further explored potential sources of heterogeneity among the examined variables—i.e., gender, age, year of publication and country. When modeling country as three macro-areas, studies from Western/Northern Europe showed lower eco-anxiety than Mediterranean/Eastern countries (β = −11.4 POMP; 95% CI: −23.5 to 0.6; p = 0.063), and Non-European samples were even lower (β = −18.1 POMP; 95% CI: −34.6 to −1.6; p = 0.033). This supports a gradient whereby Mediterranean/Eastern contexts exhibit the highest mean scores, followed by Western/Northern Europe and then Non-European samples. The association with publication year is non-significant (β = +1.5 POMP per year; 95% CI: −2.7 to 5.7; p = 0.48). These differences, although indicative, should be interpreted cautiously due to the heterogeneity in sample characteristics (students, workers, general population) and cultural as well as environmental contexts. However, these findings highlight the robustness of eco-anxiety as a measurable construct across diverse populations and contexts, while also emphasizing the role of methodological and cultural factors in shaping the magnitude of observed effects. The pooled estimates, along with the prediction interval, provide a reliable benchmark for future studies and for policymakers interested in monitoring eco-anxiety as an emerging public health concern, especially among some populations.

Several studies reported sex-disaggregated data, consistently indicating higher scores among women compared with men. Across the 15 studies reporting such data, the standardized mean difference (SMD) between women and men ranged from 0.15 to 0.45, corresponding to approximately 4–9 POMP points. On average, the difference was 0.30 SMD (6 POMP points; women ≈44/100; men 38/100; Q_between, p < 0.05). The meta-regression (REML) revealed no significant association between mean age and climate anxiety (β = −0.37 per year; 95% CI: −0.82 to +0.08; p = 0.11), indicating only a trend to report higher scores for younger groups. When the country was modeled as a predictor, Western/Northern European samples scored 11 POMP points lower than Mediterranean/Eastern countries (p = 0.06), and Non-European samples 18 points lower (p = 0.03). Excluding studies rated as lower quality (NOS = Poor) did not materially change the pooled estimates (pooled mean 34/100), supporting the robustness of the results.

Finally, sample size was not associated with effect size, and incomplete demographic reporting prevented a reliable multivariable assessment including age and sex simultaneously across all studies.

4. Discussion

A high variability emerged from the analysis of the available literature on eco-anxiety. Though our meta-analysis approach considered only those studies that were based on validated tools, it was found that the use of different assessment methods accounts for a great part of the heterogeneity found among the selected studies. This confirms the previously acknowledged gaps in eco-anxiety characterization and highlights the need for standardized research in this field [10].

The most significant focus of this research is the possible role of demographic variables such as gender and age in defining the way individuals experience eco-anxiety. Notably, the evidence suggests a gendered dimension for eco-anxiety, with the majority of the studies that examined gender as a variable identifying a significant association with females. In this regard, the literature shows that anxiety and related disorders in general are roughly twice as prevalent in women compared to men, and this may explain the gender difference observed in our study as a reflection of broader gender disparities in general anxiety and depression incidence, mainly due to exposure to stressful life events and biological factors [95]. Furthermore, this finding is in line with those of a recent review of the literature, which related gender differences in eco-anxiety to physiological and socioeconomic aspects such as women’s anatomy and lower access to cooling and sanitation facilities worldwide [96].

Similarly, age emerged as a critical determinant, with younger individuals consistently exhibiting higher levels of eco-anxiety. This trend may reflect greater awareness or concern about future environmental conditions among younger generations, who are likely to experience potentially harmful medium- to long-term consequences of climate change more acutely than others [16,38,39,40,41,42,44,55,57,64,65,67,74,80,81,84,87,92].

Both gender and age were shown to be related to climate change, even in a recent meta-analysis examining 33 correlates from 94 studies [97]. However, it should be noted that in our meta-regression analysis, the relationship between eco-anxiety and gender was confirmed, while that with age was not significant. This suggests that other age-related variables, such as educational level or environmental awareness, can play a role as mediators or bias sources in this relationship. Further research is needed to explore these aspects in depth.

These findings underline the value of exploring the interplay between demographic variables and the psychological dimensions of eco-anxiety, as such an approach provides insights into how diverse populations perceive and emotionally respond to the environmental crisis. Understanding these complexities makes it possible to tailor interventions for specific groups but also opens the door to examining the broader psychological implications of eco-anxiety. For instance, climate change anxiety has been frequently linked to general anxiety and depression [16,33,46,54,55,62,64,66,72,74,78,86,93], suggesting that it may both overlap with and exacerbate existing mental health challenges. Eco-anxiety can manifest through cognitive, emotional, and behavioral responses, such as persistent worries, psychological distress, or sleep disturbances. Concerns about environmental issues can also disrupt individuals’ ability to participate in work, education, or personal relationships, leading to functional impairments [16]. While eco-anxiety may amplify emotional distress, it is also closely linked to increased engagement in pro-environmental behaviors, as higher levels of worry or anxiety about climate phenomena have been shown to correspond with a stronger commitment to actions aimed at mitigating its effects [10]. Anxiety is an adaptive mechanism that encompasses cognitive and affective dimensions, prompting problem-solving behaviors aimed at reducing perceived risks [12]. The dual nature of eco-anxiety is highlighted by its role as both a psychological burden and a potential motivator for constructive environmental action, pointing to the need for interventions that balance emotional support with empowerment to act [98,99,100].

Finally, when considering the meta-regression results regarding the geographical distribution of selected studies, the higher values registered in countries overlooking the Mediterranean Sea suggest that exposure to a mild climate such as that of the Mediterranean Basin may increase the probability of developing eco-anxiety [96]. This factor, together with cultural and social differences among countries, should be studied in depth as a possible predictor.

However, some limitations should be considered when interpreting these results. One significant limitation is the considerable variability across the selected studies in terms of populations, variables, and methodologies, which can influence how eco-anxiety is experienced and reported. A particularly challenging aspect was the inconsistency in the methods used to assess eco-anxiety, with studies relying on self-reported measures, and employing different scales or questionnaires. This lack of standardization in assessment tools introduces variability in how eco-anxiety is defined, measured, and reported, limiting the ability to aggregate the findings meaningfully. We have tried to overcome this issue by performing a meta-regression analysis. Furthermore, due to its aim, our review considered only cross-sectional studies; analyzing longitudinal studies could better contribute to characterizing the determinants of eco-anxiety. In addition, we included articles published in the English or Italian language, and we did not consider the grey literature in our search; this could have generated selection biases, maybe overlooking the presence of eco-anxiety in some populations worldwide. Considering that significant geographical differences emerged from the meta-regression analysis, this aspect should be addressed in future studies.

Nevertheless, our findings highlighted some common aspects that should be considered when planning policies aimed at mitigating the health effects of climate change. These include the importance of recognizing the cognitive and emotional responses to environmental worsening, such as eco-anxiety, as well as the need for targeted interventions that consider demographic factors like people’s gender and residence. By focusing on these aspects, effective strategies aimed at addressing environmental concerns while supporting mental well-being and encouraging pro-environmental behaviors could be created.

5. Conclusions

With the climate crisis becoming more urgent, eco-anxiety represents a growing phenomenon that needs to be considered by public health authorities. Evidence regarding the dimensions and correlates of eco-anxiety shows great variability. Therefore, more specific and homogeneous research in this field is needed.

However, the findings of this review highlight the importance of considering demographic factors in understanding eco-anxiety, as they can highlight how different groups perceive and react to the environmental crisis, revealing the more vulnerable categories to which interventions should be primarily addressed. In particular, the meta-analysis of the literature shows that eco-anxiety affects women more than men and some countries more than others. Governments, especially those of the most interested countries, should then tackle this issue by identifying the most appropriate methods and settings to communicate risks and enhance people’s resilience to environmental challenges.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare13212716/s1, Table S1: PRISMA checklist; Table S2: PRISMA abstract checklist; Table S3: NOS-based quality evaluation of the selected studies; Table S4: Data used in the meta-regression analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P., F.G. (Francesca Gallè), F.V. and C.N.; Methodology, C.P., F.G. (Francesca Gallè) and F.V.; Investigation, A.D.G., E.M. and F.G. (Fabiano Grassi); Formal analysis, A.D.G., E.M. and F.G. (Fabiano Grassi); Supervision, C.P., F.G. (Francesca Gallè) and F.V.; Writing—original draft, A.D.G., E.M. and F.G. (Francesca Gallè); Writing—review and editing, C.P., F.G. (Francesca Gallè), F.V. and C.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAS | Climate Anxiety Scale |

| CCAS | Climate Change Anxiety Scale |

| CCAQ | Climate Change Anxiety Questionnaire |

| CCASWH | Climate Change Anxiety Scale for Women’s Health |

| CCWS | Climate Change Worry Scale |

| CSI | Children’s Stress Index (CSI) |

| DASS-21 | Depression Anxiety Stress Scale |

| EAQ | Eco-Anxiety Questionnaire |

| EC | Environmental Crisis |

| EWS | Eco-Worry Scale |

| GAD-7-C | Generalised Anxiety Disorder scale anxiety |

| HEAS | Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale |

| HINT | Habit Index of Negative Thinking |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

References

- Cissé, G.; McLeman, R.; Adams, H.; Aldunce, P.; Bowen, K.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Clayton, S.; Ebi, K.L.; Hess, J.; Huang, C.; et al. Health, wellbeing, and the changing structure of communities. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Knutti, R. Closing the Knowledge-Action Gap in Climate Change. One Earth 2019, 1, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trewin, B.; Cazenave, A.; Howell, S.; Huss, M.; Isensee, K.; Palmer, M.D.; Tarasova, O.; Vermeulen, A. Headline Indicators for Global Climate Monitoring. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 2021, 102, E20–E37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Health and Climate Change Survey Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240038509 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Budziszewska, M.; Jonsson, S.E. Talking about climate change and eco-anxiety in psychotherapy: A qualitative analysis of patients’ experiences. Psychotherapy 2002, 59, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggal, D. Oxford reveals Word of the Year 2019: Here’s Why We Should be Very, Very Concerned. The Economic Times. 2022. Available online: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/magazines/panache/oxford-reveals-word-of-the-year-2019-heres-why-we-should-be-very-very-concerned/articleshow/72332446.cms?from=mdr (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- American Psychological Association (APA). Mental Health and Our Changing Climate: Impacts, Implications and Guidance. 2017. Available online: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2017/03/mental-health-climate.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Clayton, S.; Manning, C.; Krygsman, K.; Speiser, M. Mental Health and Our Changing Climate: Impacts, Implications, and Guidance; American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/mental-health-climate-change.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Climate Psychology Alliance. The Handbook of Climate Psychology. 2020. Available online: https://www.climatepsychologyalliance.org/images/files/handbookofclimatepsychology.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Coffey, Y.; Bhullar, N.; Durkin, J.; Islam, M.S.; Usher, K. Understanding eco-anxiety: A systematic scoping review of current literature and identified knowledge gaps. J. Clim. Change 2021, 3, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; de Vries, W.; de Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Anxiety and the ecological crisis: An analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, G. Chronic environmental change: Emerging ‘psychoterratic’ syndromes. In Climate Change and Human Well-Being: Global Challenges and Opportunities; Weissbecker, I., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ojala, M.; Cunsolo, A.; Ogunbode, C.A.; Middleton, J. Anxiety, worry, and grief in a time of environmental and climate crisis: A narrative review. Ann. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2021, 46, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First, M.B.; Yousif, L.H.; Clarke, D.E.; Wang, P.S.; Gogtay, N.; Appelbaum, P.S. DSM-5-TR: Overview of what’s new and what’s changed. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 218–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, S.; Karazsia, B.T. Development and validation of a measure of climate change anxiety. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepp, J.; Klein, S.A.; Horsten, L.K.; Urbild, J.; Lane, S.P. Introduction and behavioral validation of the climate change distress and impairment scale (CC-DIS). Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S. Anxiety disorders, climate change, and the challenges ahead: Introduction to the special issue. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 76, 102313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ágoston, C.; Urbán, R.; Nagy, B.; Csaba, B.; Kőváry, Z.; Kovács, K.; Varga, A.; Dúll, A.; Mónus, F.; Shaw, C.A.; et al. The psychological consequences of the ecological crisis: Three new questionnaires to assess eco-anxiety, eco-guilt, and ecological grief. Clim. Risk Manag. 2022, 37, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higginbotham, N.; Connor, L.; Albrecht, G.; Freeman, S.; Agho, K. Validation of an environmental distress scale. Ecohealth 2007, 3, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, T.L.; Stanley, S.K.; O’Brien, L.V. Synthesising psychometric evidence for the climate anxiety scale and Hogg eco-anxiety scale. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 88, 102003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Pihkala, P.; Wray, B.; Marks, E. Psychological and emotional responses to climate change among young people worldwide: Differences associated with gender, age, and country. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses; Ottawa Hospital Research Institute: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2000; Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Shi, J.; Luo, D.; Weng, H.; Zeng, X.-T.; Lin, L.; Chu, H.; Tong, T. Optimally estimating the sample standard deviation from the five-number summary. Res. Synth. Methods 2020, 11, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, S.; Zhao, X.; Steele, R.; Thombs, B.D.; Benedetti, A.; DEPRESsion Screening Data (DEPRESSD) Collaboration. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from commonly reported quantiles in meta-analysis. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2020, 29, 2520–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, P.; Cohen, J.; Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. The problem of units and the circumstance for POMP. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1999, 34, 315–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S.M.; El-Monshed, A.H.; Khedr, M.A.; Morsy, O.M.I.; El-Ashry, A.M. Future nurses in a changing climate: Exploring the relationship between environmental literacy and climate anxiety. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asiamah, N.; Mensah, H.K.; Ansah, E.W.; Eku, E.; Ansah, N.B.; Danquah, E.; Yarfi, C.; Aidoo, I.; Opuni, F.F.; Agyemang, S.M. Association of optimism, self-efficacy, and resilience with life engagement among middle-aged and older adults with severe climate anxiety: Sensitivity of a path model. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 380, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, M.H.R.; Zoromba, M.A.; El-Gazar, H.E.; Loutfy, A.; Elsheikh, M.A.; El-Ayari, O.S.M.; Sehsah, I.; Elzohairy, N.W. Climate anxiety, environmental attitude, and job engagement among nursing university colleagues: A multicenter descriptive study. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimsir, E.; Sahin, M.D.; Akdogan, R. Unveiling the relationships between eco-anxiety, psychological symptoms and anthropocentric narcissism: The psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale. Glob. Ment. Health 2024, 11, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daeninck, C.; Kioupi, V.; Vercammen, A. Climate anxiety, coping strategies and planning for the future in environmental degree students in the UK. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1126031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feather, G.; Williams, M. The moderating effects of psychological flexibility and psychological inflexibility on the relationship between climate concern and climate-related distress. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2022, 23, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraci, A.; Giordano, G.; Cucinella, N.; Cannavò, M.; Cavarretta, M.V.; Alesi, M.; Caci, B.; D’aMico, A.; Gentile, A.; Iannello, N.M.; et al. Psychological dimensions associated with youth engagement in climate change issues: A person-centered approach. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 25836–25846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezgin Yazıcı, H.; Ökten, Ç.; Utaş Akhan, L. Climate change anxiety and sleep problems in the older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2025, 29, 1456–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökçeli, F.K.; Akkaya, M.Ö. The link between eco-anxiety and nature relatedness in associate degree students. J. Balt. Sci. Ed. 2025, 24, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülırmak Güler, K.; Albayrak Günday, E. Nature-friendly hands: The relationship between nursing students’ climate change anxiety, intolerance of uncertainty, and anxiety about the future. Public Health Nurs. 2024, 41, 1491–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajek, A.; König, H.H. Climate anxiety in Germany. Public Health 2022, 212, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; König, H.-H. Climate anxiety, loneliness and perceived social isolation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; Koenig, H.-H. Climate anxiety and mental health in Germany. Climate 2023, 11, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; König, H.-H. Do individuals with high climate anxiety believe that they will die earlier? First evidence from Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; Koenig, H.-H. Belief in science and climate anxiety: Findings from a quota-sample. J. Public Health 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlaci Baskaya, Y.; Unlu Bidik, N.; Yolcu, B. The effect of level of anxiety about climate change on the use of feminine hygiene products. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2024, 165, 1158–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heeren, A.; Mouguiama-Daouda, C.; Contreras, A. On climate anxiety and the threat it may pose to daily life functioning and adaptation: A study among European and African French-speaking participants. Clim. Change 2022, 173, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heeren, A.; Mouguiama-Daouda, C.; McNally, R.J. A network approach to climate change anxiety and its key related features. J. Anxiety Disord. 2023, 93, 102625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzel, S.; Tschorn, M.; Schulte-Hutner, M.; Schäfer, F.; Reese, G.; Pohle, C.; Peter, F.; Neuber, M.; Liu, S.; Keller, J.; et al. Anxiety in response to the climate and environmental crises: Validation of the Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale in Germany. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1239425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henschel, L.D.; Franke, G.H.; Jagla-Franke, M. Psychometric properties of the German Hogg Eco-Anxiety scale and its associations with psychological distress, self-efficacy and social support. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herve, F.; Marsat, S. Eco-anxiety, connectedness to nature, and green equity investments. Econ. Bull. 2023, 43, 1485–1492. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, T.L.; Stanley, S.K.; O’Brien, L.V.; Wilson, M.S.; Watsford, C.R. The Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale: Development and validation of a multidimensional scale. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 71, 102391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, T.L.; Stanley, S.K.; O’Brien, L.V.; Watsford, C.R.; Walker, I. Clarifying the nature of the association between eco-anxiety, wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 95, 102249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holler, Y.; Zelinski, L.; Sesseljuson, L.D.; Palmadottir, A.D.; Latini, A.; Matthews, A.; Asmundsdottir, Á.M.; Gudmundsson, L.S.; Olafsson, R.P. Worries about air pollution from the unsustainable use of studded tires and cruise ships—A preliminary study on the relationship between worries and health complaints due to seasonal pollution. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocenti, M.; Perilli, A.; Santarelli, G.; Carluccio, N.; Zjalic, D.; Acquadro Maran, D.; Ciabini, L.; Cadeddu, C. How does climate change worry influence the relationship between climate change anxiety and eco-paralysis? A moderation study. Climate 2023, 11, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocenti, M.; Santarelli, G.; Lombardi, G.S.; Ciabini, L.; Zjalic, D.; Di Russo, M.; Cadeddu, C. How can climate change anxiety induce both pro-environmental behaviours and eco-paralysis? The mediating role of general self-efficacy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalin, H.; Chandes, C.; Boudoukha, A.-H.; Jacob, A.; Poinsot, R.; Congard, A. Better understanding eco-anxiety: Creation and validation of EMEA scale. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2025, 75, 101010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalin, H.; Sapin, A.; Macherey, A.; Boudoukha, A.H.; Congard, A. Understanding eco-anxiety: Exploring relationships with environmental trait affects, connectedness to nature, depression, anxiety, and media exposure. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 23455–23468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.J.; Chung, S.J.; Lee, H. Validation of the Climate Change Anxiety Scale for Korean adults. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2023, 2023, 9718834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Vazquez, D.; Piqueras, J.-A.; Espinosa-Fernandez, L.; Canals-Sans, J.; Garcia-Lopez, L.-J. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the climate anxiety scale in Spanish-speaking adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1631481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabasakal-Cetin, A. Association between eco-anxiety, sustainable eating and consumption behaviors and the EAT-Lancet diet score among university students. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 111, 104972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, S.; Brandt, L.; Luykx, J.J.; Dom, G. Impact of climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution on the incidence and manifestation of depressive and anxiety disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2025, 38, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, L.; Keles, E.; Baydili, K.N.; Kaya, Z.; Kumru, P. Impact of climate change education on pregnant women’s anxiety and awareness. Public Health Nurs. 2025, 42, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenstler, M.; Shelley, G. Love of nature in the time of climate change: Environmental science undergraduates report higher levels of nature-relatedness and eco-anxiety but not resilience. Ecopsychology 2024, 16, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kos, A.; Novak Zabukovec, V.; Jug, V. The role of eco-anxiety in reproductive wish during emerging adulthood. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratz, S.; McEwan, K. From roots to action: How adolescent nature exposure and adult eco-anxiety foster pro-environmental behavior. Curr. Psychol. 2025, 44, 15270–15279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryazh, I.; Baranov, V. Psychometric evaluation of the Ukrainian version of the Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale (HEAS-UA); (HEAS-UA)]. Insight 2025, 13, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionow, P.; Sołtys, M.; Izdebski, P.; Mudło-Głagolska, K.; Golonka, J.; Demski, M.; Rosińska, M. Climate change anxiety assessment: The psychometric properties of the Polish version of the Climate Anxiety Scale. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 870392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionow, P.; Gawrych, M.; Michalak, M.; Mudło-Głagolska, K.; Preece, D.A.; Stewart, A.E. The Climate Change Worry Scale (CCWS) and its links with demographics and mental health outcomes in a Polish sample. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionow, P.; Michalak, M.; Mudło-Głagolska, K.; Mazur, M.; Gawrych, M.; Komorowska, K.; Preece, D.A. Measuring Eco-Anxiety with the Polish Version of the 13-Item Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale (HEAS-13): Latent Structure, Correlates, and Psychometric Performance. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Garcia, L.; Latorre, F.; Vecina, M.L.; Diaz-Silveira, C. What drives pro-environmental behavior? Investigating the role of eco-worry and eco-anxiety in young adults. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, P.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Newman, D.B. Eco-anxiety in daily life: Relationships with well-being and pro-environmental behavior. Curr. Res. Ecol. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 4, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduneme, E. Some slice of climate anxiety … Is good: A cross-sectional survey exploring the relationship between college students media exposure and perceptions about climate change. J. Health Commun. 2024, 29 (Suppl. S1), 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maral, S.; Bilmez, H.; Satıcı, S.A. Understanding the link between environmental identity, eco-anxiety, intolerance of uncertainty and mental well-being. Psychiatr. Q. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathers-Jones, J.; Todd, J. Ecological anxiety and pro-environmental behaviour: The role of attention. J. Anxiety Disord. 2023, 98, 102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memiç-İnan, C.; Şarahman-Kahraman, C.; Topal, İ.; Toptaş, S. Anxiety for the planet, health for the body: The relationship between eco-anxiety and the Mediterranean diet in Turkish young adults. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 6417–6423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micoulaud-Franchi, J.-A.; Coelho, J.; Geoffroy, P.A.; Vecchierini, M.-F.; Poirot, I.; Royant-Parola, S.; Hartley, S.; Cugy, D.; Gronfier, C.; Gauld, C.; et al. Eco-anxiety: An adaptive behavior or a mental disorder? Results of a psychometric study. L’Encéphale 2024, 50, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.J.; Ahmed, S.M.; Qadr, M.Q.; Blbas, H.; Ali, A.N.; Saber, A.F. Climate change anxiety symptoms in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. J. Pioneer. Med. Sci. 2025, 14, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrù, L.; Taccini, F.; Mannarini, S. Worry about the future in the climate change emergency: A mediation analysis of the role of eco-anxiety and emotion regulation. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmentier, M.-L.; Weiss, K.; Aroua, A.; Betry, C.; Rivière, M.; Navarro, O. The influence of environmental crisis perception and trait anxiety on the level of eco-worry and climate anxiety. J. Anxiety Disord. 2024, 101, 102799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plohl, N.; Mlakar, I.; Musil, B.; Smrke, U. Measuring young individuals’ responses to climate change: Validation of the Slovenian versions of the Climate Anxiety Scale and the Climate Change Worry Scale. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1297782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, M.E.S.; Carmen, B.P.B.; Luminarias, M.E.P.; Mangulabnan, S.A.N.B.; Ogunbode, C.A. An investigation into the relationship between climate change anxiety and mental health among gen Z filipinos. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 7448–7456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocchi, G.; Pileri, J.; Luciani, F.; Gennaro, A.; Lai, C. Insights into eco-anxiety in Italy: Preliminary psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Hogg Eco-anxiety Scale, age and gender distribution. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 92, 102180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Quiroga, A.; Peña Loray, J.S.; Moreno Poyato, A.; Roldán Merino, J.; Botero, C.; Bongiardino, L.; Aufenacker, S.I.; Stanley, S.K.; Costa, T.; Luís, S.; et al. Mental health during ecological crisis: Translating and validating the Hogg Eco-anxiety Scale for Argentinian and Spanish populations. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, F.; Costa, T.; Teixeira-Santos, L.; de Pinho, L.G.; Sequeira, C.; Luís, S.; Loureiro, A.; Soro, J.C.; Roldán Merino, J.; Moreno Poyato, A.; et al. Validating a measure for eco-anxiety in Portuguese young adults and exploring its associations with environmental action. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, P.D.; Pakingan, K.A.; Aruta, J.J.B.R. Measurement of climate change anxiety and its mediating effect between experience of climate change and mitigation actions of Filipino youth. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2022, 39, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeiryte, A.; Liobikiene, G. Emotions related to climate change, and their impact on environmental behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 488, 144659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, S.; Zhou, D.; Charan, I.A. The effects of climate change on mental health and psychological well-being: Impacts and priority actions. Glob. Ment. Health 2024, 11, e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subasi Turgut, F.; Ozturk, M. Worrying about individual health and worrying about ecological health; the relationship between eco-anxiety and health. Klin. Psikiyatri Derg. 2025, 28, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.-P.; Chan, H.-W.; Clayton, S. Perception of global norm of government climate action and support for domestic climate policies. J. Environ. Psy. 2025, 89, 102507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifunovic, M.; Rajcevic, V. How does eco-anxiety among geography teachers affect their performance? Evidence from the banja luka region (b&h). J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijic Sasa 2024, 74, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucholska, K.; Gulla, B.; Ziernicka-Wojtaszek, A. Climate change beliefs, emotions and pro-environmental behaviors among adults: The role of core personality traits and the time perspective. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0300246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecina, M.L.; Alonso-Ferres, M.; Díaz-Silveira, C. Eco-anxiety or simply eco-worry? Incremental validity study in a representative Spanish sample. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1560024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimann, B.; Opalinski, K. Facing climate change: The mediating role of pro-ecological behaviour between climate anxiety and psychological adaptation. J. Psychiatry Clin. Psychol. 2024, 24, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; Player, L.; Jiongco, A.; James, M.; Williams, M.; Marks, E.; Kennedy-Williams, P. Climate anxiety: What predicts it and how is it related to climate action? J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 83, 101866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wullenkord, M.C.; Troeger, J.; Hamann, K.R.S.; Loy, L.S.; Reese, G. Anxiety and climate change: A validation of the Climate Anxiety Scale in a German-speaking quota sample and an investigation of psychological correlates. Clim. Change 2021, 168, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesildere Saglam, H.; Mizrak Sahin, B. The impact of climate change anxiety on premenstrual syndrome: A cross-sectional study. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2025, 31, e14177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergi, M.R.; Picconi, L.; Tommasi, M.; Saggino, A.; Ebisch, S.J.H.; Spoto, A. The Role of Gender in the Association Among the Emotional Intelligence, Anxiety and Depression. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 747702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gayathri, K.G.; Vijayalakshmi, P.; Krishnan, S.; Rekha, S.; Latha, P.K.; Venugopal, V. Exploring eco-anxiety among women amid climate-induced heat: A comprehensive review. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1480337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühner, C.; Gemmecke, C.; Hüffmeier, J.; Zacher, H. Climate change anxiety: A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Change 2025, 93, 103015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L.M.; Hatch, A.; Johnson, A. Cross-national gender variation in environmental behaviors. Soc. Sci. Q. 2004, 85, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeny, K.; Dooley, M.D. The surprising upsides of worry. Soc. Personal Psychol. Compass 2017, 11, e12311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Leviston, Z.; Hurlstone, M.; Lawrence, C.; Walker, I. Emotions predict policy support: Why it matters how people feel about climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 2018, 50, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).