Abstract

Background/Objectives: This study aimed to identify factors associated with harmful behavior toward others based on existing research. Methods: This scoping review focused on individuals at risk of harming others due to mental health issues, with the target population encompassing three settings: the community, inpatient facilities with frequent admissions and discharges, and healthcare settings where medical treatment is sought. A scoping review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews. The terms violence, aggression, problem behavior, and workplace violence were used to search for related literature, subsequently selecting systematic reviews. Results: A total of 24 papers were ultimately included. From the included papers, background factors (demographic, personal history, and clinical aspects); situational factors (social connection status, daily life status); psychological factors; antecedents of harmful behavior; and triggers of harmful behavior were extracted as factors associated with harmful behavior. Conclusions: Our results indicate that background and situational factors lead to harmful behavior toward others, disruptions in the harmony between these factors cause disturbances in psychological processes, and harmful behavior toward others is triggered by stimuli that promote such behavior. Considering that all studies reviewed herein involved inpatients in medical settings, further research is required to identify the factors associated with harmful behaviors occurring in the community.

1. Introduction

Harmful behavior toward others, such as committing actual physical violence against another person or property or making specific and imminent verbal threats, can cause emotional or physical trauma [1,2]. However, no generalized standards for harmful behavior toward others yet exist, and defining such behaviors for the purpose of establishing laws has proven difficult [3].

In Japan, the Mental Health and Welfare Law defines “other harmful acts” as “acts that harm the life, body, chastity, honor, property, or social interests of others, such as murder, injury, assault, sexual problem behavior, insult, damage to property, robbery, extortion, theft, fraud, arson, and tampering with fire”. For persons at risk of causing other people harm due to mental disorders, compulsory hospitalization is enforced by order of the prefectural governor when necessary to ensure the safety of the person concerned, his/her family, and local residents and to provide appropriate treatment [4,5]. Mental health welfare professionals in the community are charged with managing people at risk of causing harm to others, including emergency response and crisis intervention for those at risk of causing harm to others. Mental health welfare professionals working at public health centers, which are the frontline public health organizations, facilitate involuntary hospitalization, if necessary, after examination by a designated mental health physician based on a police report, etc. [6]. However, if the police report indicates no risk of harm to others even after examination by a designated mental health doctor or if the patient was violent but had calmed down by the time the police arrived, the patient would not be subjected to involuntary hospitalization but would instead be left with the mental health welfare professionals who would be managing the case thereafter. Mental health welfare specialists stationed in various municipalities provide consultation support for mental health issues and respond to consultations from family members or neighbors affected by individuals who shout, throw things, cause disturbances, or act violently [6]. Numerous individuals with mental disturbances currently receive treatment or therapy. Unfortunately, several people with mental disorders commit acts of violence during treatment or after treatment interruption, which cannot be controlled by family members or people surrounding them, despite noticing the worsening mental symptoms and changes in behavior prior to committing acts of violence. Hence, responding to acts of violence in hospitals and local communities is becoming increasingly important [7,8].

Several countries worldwide, including many European countries, the United States, Oceania countries, and Asian countries, among others, have taken measures, such as involuntary hospitalization, to control those at risk of harming others based on their psychiatric symptoms [5], given the rising need for managing such cases within the community. In addition, aggression and violence toward others have become a major problem in the medical field, such as psychiatric wards. Considering that acts of harm in medical settings not only cause injury to staff and other patients but also affect staff morale and the effectiveness of treatment provided to other patients [9], research has sought to clarify the characteristics of persons at high risk of committing acts of harm [9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Accordingly, studies have found that risk factors for aggression and violence in medical settings can be categorized into internal and external factors. Internal factors include clinical factors (e.g., schizophrenia and bipolar disorder); personal factors (e.g., impulsivity, hostility, and poor insight); historical factors (e.g., past violence and low social class); and drug and alcohol abuse. Meanwhile, external factors include environmental factors (e.g., the ward environment), hospitalization factors (e.g., involuntary hospitalization and length of stay), and relational factors (e.g., interpersonal relationships with staff) [10]. Six domains identify the key influences over conflict and containment rates within psychiatric wards: the patient community, patient characteristics, the regulatory framework, the staff team, the physical environment, and outside hospital. Furthermore, triggers of conflict, such as violence, have been identified, including refusal of patient requests, arguments with friends and family, and curtailment of freedoms [7].

Both health facilities and communities need to establish appropriate responses to persons who may cause harm. In the community, the internal factors of persons who may cause harm often cannot be determined when providing a response, and their living environment and relationships with other people vary. Previous studies on harmful behavior toward others have focused on cases occurring in medical facilities, specific diseases, and the acute stage; thus, factors associated with harmful behavior toward others in the community have yet to be fully clarified. We believe that clarifying the factors associated with harmful behavior toward others will help mental health welfare professionals understand such factors and assess situations that may cause harmful behavior toward others, including the degree of risk. To determine the appropriate response to persons who may cause harm in the community, clarifying factors associated with harmful behavior based on existing research is necessary. Therefore, we conducted a scoping review to obtain relevant knowledge and factors related to harmful behavior that could help in the investigation of the actual situation of harmful behavior in the community.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

Our research methodology involved a scoping review that aimed to outline the key concepts and available evidence underlying the relevant factors leading to harmful behavior toward others [16]. This study was planned and conducted in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) guidelines [17]. Before the start of the search, a review protocol was entered into the framework database (https://osf.io/g28t3) (accessed on 26 November 2024).

Our research question was as follows: “What are the factors that cause people to commit acts of harm?” Patient: A person who commits a harmful act in the community (a person who is at risk of committing a harmful act). Concept: To identify factors associated with harmful acts. Context: Exhaustive factors associated with committing a harmful act, according to the research question.

This scoping review focused on individuals living in the community who are at risk of harming others due to mental health issues. Therefore, I have defined the target population to include three settings: the community where these individuals reside, inpatient facilities due to frequent admissions and discharges, and healthcare settings where they seek medical treatment.

2.2. Literature Search and Identification

In this study, violence, aggression, and problem behavior were indicated as harmful behavior toward others. Our literature search was conducted using the PubMed and Scopus databases.

The formula “Violence OR Aggression OR Problem Behavior OR Workplace violence And systematic review” was used to search PubMed, whereas the formula “Problem Behavior OR Workplace violence And systematic review” was used to search Scopus. Only studies published in English were searched, with no restrictions on the year of publication. Although a considerable amount of data is available on harmful behavior in medical facilities and among patients with specific diseases, obtaining comprehensive data is necessary to examine factors associated with harmful behavior in the community. Therefore, a systematic review was conducted to accumulate comprehensive data from various sources.

A similar approach was used in the identification of all papers included in this study by setting the eligibility criteria before study initiation. Moreover, two reviewers independently determined whether or not the literature was acceptable [16] based on “patient” (i.e., the person who commits the harm), “concept” (i.e., a description of relevant factors leading up to the harm), and “context” (i.e., an exhaustive description of the harmful behavior). For the first screening, two researchers independently evaluated the titles and abstracts to determine whether they satisfied the eligibility criteria. Cases of disagreements among the researchers were resolved through consensus after discussing the results among themselves. In the second screening, two researchers independently read the full texts of the identified literature to confirm whether the papers satisfied the eligibility criteria. Similarly, differences in opinion were resolved through consensus after discussions among the researchers; after which, a final decision on whether to include the paper was made.

2.3. Data Extraction and Integration of the Results

The title, author, year of publication, purpose, subject, scope, and main results and discussions were extracted and organized. The main research results extracted were divided into the following categories: literature related to general behavior, such as violence and aggression, literature related to behaviors in patients with psychiatric disorders, and literature related to rating scales of factors associated with harmful behaviors toward others.

The following procedure was used to qualitatively integrate descriptions of factors related to harmful behavior in the literature [16]. All texts and rating scales obtained from the search results were carefully read to extract descriptions of the factors related to harmful behavior toward others. The extracted research results were coded by expressing them in a single sentence while ensuring that the meaning of each group was not compromised. Codes, subcategories, and categories were generated by grouping them based on their differences and commonalities. To ensure the validity of the analysis, all authors evaluated the consistency of the generated codes, subcategories, and categories in the aforementioned process and obtained unanimous agreement. The entire set of generated categories was reviewed; after which, the contents of the extracted categories were examined. We then discussed the relationships among the categories and between categories and harmful behavior toward others.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of the Included Studies

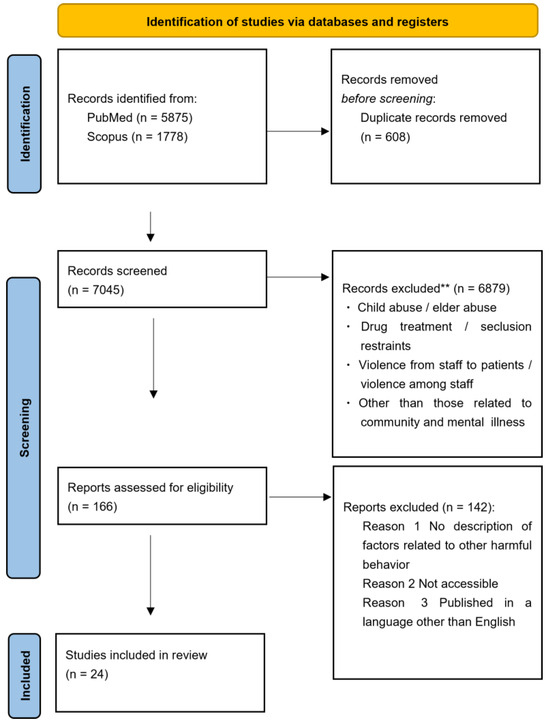

The literature search identified 7045 papers. The literature for this scoping review consists of articles that examine relevant factors contributing to harmful behavior toward others in the community, particularly in situations where mental health welfare professionals are likely to be involved. Literature on child and elder abuse, literature on drug treatment and seclusion restraints, literature on staff-to-patient and staff-to-staff violence, and literature not related to community or mental illness were excluded, because they did not fit the theme and conceptual scope of this review. After excluding 6879 and 142 papers in the primary and secondary screening, respectively, 24 papers were ultimately included (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart for the article selection process. ** Based on title/abstract screening.

Among the papers included herein, all of which were published between 2007 and 2023, 6 focused on general behaviors such as violence and aggression [3,8,12,13,18,19], 13 articles focused on behaviors among patients with psychiatric disorders [2,9,11,15,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28], and 5 focused on rating scales for factors related to harmful behaviors toward others [1,29,30,31,32]. The scope of our study included papers involving inpatients, those focusing on the community, and those in medical settings.

Table 1 provides an overview of the included papers organized according to title, author, year of publication, purpose of the study, subject matter, scope, and summary of the results and discussion.

Table 1.

Summary of the included literature.

3.2. Factors Associated with Harmful Behavior Toward Others

From the target literature (Table 1), 22 subcategories and 7 categories were extracted (Table 2), using the relevant factors for harmful behavior toward others as codes.

Table 2.

Factors related to the harmful behavior.

{Background factors (demographic and personal history)} were extracted from the following seven subcategories: <Demographic and environmental factors>, which includes four codes, such as [age]; <history of self-injurious/other harmful behavior>, which includes two codes, such as [history of violence]; <apprehension/criminal history>, which includes three codes, such as [history of criminal/criminal activity]; <violence victimization/experienced abuse>, which includes three codes, such as [experience of violence victimization]; <family history (mental illness/substance use problems/criminal involvement)>, which includes three codes, such as [family history of mental illness]; <intelligence/history of school>, which includes two codes, such as [intelligence]; and <secure attachment and conduct problems during childhood>, which includes three codes, such as [secure attachment in childhood/stable nurturing environment].

{Background factors (clinical aspects)} were extracted from the following four subcategories: <mental illness/organic disorder (schizophrenia/personality disorder/mood disorder)>, which includes 10 codes, such as [history of mental illness]; <substance use problems (alcohol/drugs)>, which includes 4 codes, such as [previous and/or current drug abuse]; <treatment status (treatment motivation/compliance/sensitivity)>, which includes 6 codes, such as [compliance/treatment motivation]; and <positive symptoms (e.g., hallucinations and delusions)>, which includes 2 codes, such as [hallucinations/delusions].

{Situational factors (daily life status)} were extracted from the following two subcategories: <work/economic situation>, which includes three codes, such as [work/work training], and <basic self-care independence>, which includes three codes, such as [self-care/ability to perform daily chores].

{Situational factors (social connection status)} were extracted from the following two subcategories: <presence and interaction with family and friends>, which includes three codes, such as [cohabitee], and <social connections and access to public and private support systems>, which includes eight codes, such as [social support/network].

{Psychological factors (thinking, cognition, and personality)} were extracted from the following five subcategories: <self-awareness/foresight>, which includes four codes, such as [understanding of mental illness and treatment needs/insight into illness and/or behavior]; <ability to put yourself in other people’s shoes (cooperation/empathy)>, which includes nine codes, such as [empathy/cooperativeness]; <impulsivity/emotional instability>, which includes four codes, such as [impulsivity/poor behavioral controls]; <vulnerability to stress/coping skills>, which includes two codes, such as [leisure/recreational activities]; and <abnormalities or distortions in personality, thinking, and behavior>, which includes five codes, such as [cognitive distortion/distortion of thought].

{Antecedents of harmful behavior} were extracted from one subcategory, namely, <imminent risk of harm to others and threatening behavior/attitude>, which includes nine codes, such as [verbal threats and physical threats].

{Triggers of harmful behavior} were extracted from one subcategory, namely, <triggers of the harmful behavior>, which includes five codes, such as [stressing circumstances].

4. Discussion

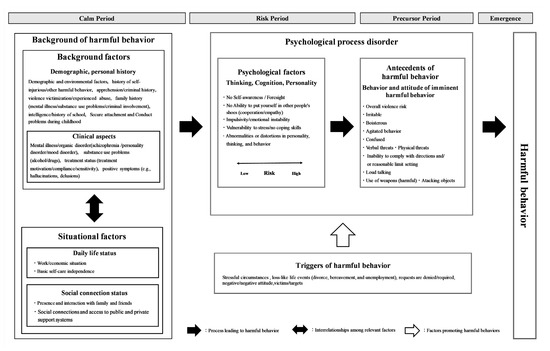

The current scoping review identified seven categories that could be considered factors associated with harmful behavior toward others (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relevance model of the factors associated with harmful behavior toward others.

Initially, the intricate intertwining of background and situational factors form the framework for the harmful behavior. Accordingly, a disturbance in the harmony between background and situational factors shifts the psychological state of an individual to one in which thoughts, cognitions, and personalities (i.e., psychological factors for harmful behavior) emerge. Further deterioration of the psychological state in situations where psychological factors are emerging brings out behaviors and attitudes antecedent to harmful behavior toward others. Consequently, the emergence of behaviors and attitudes that serve as precursors to harmful behavior can lead to actual harmful behavior toward others in the presence of some triggers.

4.1. Background of Harmful Behavior Toward Others

Background and situational factors do not directly contribute to harmful behavior toward others.

The background factors {demographic and personal history} are cultivated in an individual throughout their life and serve as the basis for related factors that influence other related factors. Clinical aspects, which are factors related to mental illness and treatment status, are the most important factors leading to harmful behavior toward others [23]. Factors related to personal history, such as family history, intelligence, and childhood upbringing, influence the incidence and symptoms of mental illness [33,34,35]. In addition, clinical aspects, such as symptoms of mental illness and lack of treatment compliance, have been associated with difficulties in establishing relationships and social ties [36,37,38], employment difficulties, deprivation, and the inability to build an independent life [38,39]. Thus, background factors form {clinical aspects} based on {demographic and personal history} and influence situational factors.

The situational factor {daily living status} determines the stability of a person’s daily life, including financial problems and self-care situation, whereas {social connection status} determines the presence or absence of family members and surrounding support persons [37]. Interventions targeting both of these factors have been shown to reduce the risk of committing harmful behavior [15]. Given that the quality of life of persons with mental illness is related to their social networks [40], situational factors are interrelated with their inability to build relationships with those around them due to the lack of a stable daily life and the inability to lead an independent daily life resulting from the lack of necessary support caused by weak social ties. Furthermore, social isolation creates a situation that facilities failure of symptom control and worsening of mental illness [38]. In this way, the factors such as {daily life status} and {social connection status} become interrelated, creating situational factors that contribute to harmful behavior and influence background factors such as clinical aspects.

Should background and situational factors achieve harmony, such as in individuals capable of self-care with a surrounding support system, it is possible to remain in the “calm period”, where one can continue with daily life without the appearance of psychological factors for harmful behavior even with worsening mental symptoms. However, when situational factors worsen due to clinical deterioration, such as a worsening of psychiatric symptoms, the patient enters the “risk period” characterized by a disturbance in the harmony between background and situational factors and the emergence of psychological factors that lead to harmful behavior toward others.

4.2. Disorders in the Psychological Processes: Psychological Factors, Antecedents of Harmful Behavior

Disorders in the psychological process is a psychological state (psychological factors and antecedents of harmful behavior) that emerges when background and situational factors for harmful behavior become discordant.

{Psychological factors} refer to a state in which the harmony between background and situational factors for harmful behavior is disrupted, creating distortions in thoughts, cognitions, and personalities. Psychological states, such as a lack of insight and cooperation and impulsivity, are caused by clinical aspects such as mental disorders and are formed in relation to social and daily functioning [40,41]. In this situation, thoughts, cognitions, and personalities (i.e., psychological factors for harmful behavior) emerge due to the deterioration of clinical aspects, such as psychiatric symptoms, which are exacerbated by situational factors, such as a lack of social support and the inability to lead an independent life, and a disruption in harmony between background and situational factors for harmful behavior.

{Antecedents of harmful behavior}, which refer to behaviors and attitudes that are precursors to harm, emerge when psychological factors, such as thoughts, cognition, and personality, are present and are further aggravated by the psychological state. The presence of hyperactivity, agitation, and accelerated motor activity in persons with mental illness has been associated with imminent aggression, and antecedents to harmful behavior toward others may be the only visible sign observed in patients at imminent risk [42]. Behaviors and attitudes that are antecedents to harmful behavior toward others are identified as dynamic factors in rating scales and can be targeted by intervention to reduce the risk of harmful behavior [15]. In this situation, a person who is impulsive or lacks insight exhibits behaviors such as throwing things or irritable attitudes that result from worsening psychological conditions due to stress.

During the “risk period” when disturbances in the psychological process occur, further deterioration in the psychological state leads to the “precursor period”. In addition, exposure to triggers of harmful behavior toward others during the “precursor period” leads to the “emergence period” when the harmful behavior emerges.

4.3. Triggers of Harmful Behavior (Triggers)

{Triggers of harmful behavior} refer to events or objects (triggers) that serve as triggers for the transition from a situation in which psychological factors (i.e., thoughts, cognitions, and personalities) emerge to that in which behaviors and attitudes that serve as precursors to harmful behavior emerge or from a situation in which behaviors and attitudes that serve as precursors to harmful behavior are observed to that in which harmful behavior toward others occurs. Considering that external stressors increase stress and excitement and induce the emergence of aggression [14], external factors, such as situations and events, can serve as triggers for the occurrence of harmful behavior toward others. Triggers of harmful behavior include factors that promote such harmful behavior by affecting disturbances in psychological processes.

Exposure to triggers of harmful behavior, such as a loss-like life event or encounter with a certain person in the presence of behaviors and attitudes that act as precursors to harmful behavior, such as being irritable or verbally threatening, can lead to actual harmful behavior, such as physical violence or problematic behavior.

4.4. Limitations

This scoping review was conducted using two databases for the search. As the review focused on systematic reviews, primary research articles and special feature articles were excluded. Additionally, a large proportion of the included literature originated from European and American countries. Therefore, there is a potential for selection bias.

The current study identified factors associated with harmful behavior toward others through a systematic review of studies on harmful behavior and discussed the relevance of these factors. However, the literature included in this review is based on inpatients in medical settings. Hence, further investigations are needed to clarify the associated factors for harmful behavior occurring in the community. We believe it necessary to focus on situational factors related to daily life and social connections, antecedents of harmful behavior, and triggers of harmful behavior in the community, which may differ from those in medical settings.

Future studies should investigate the actual conditions for harmful behavior in the community, as well as support for individuals exhibiting such behavior, based on the related factors and their associations presented herein while refining the model for factors related to harmful behavior to make it suitable for use in community settings.

5. Conclusions

Seven categories of factors related to the harmful behavior were extracted from the literature and rating scales: background factors (demographic and personal history and clinical aspects), situational factors (social connection status and daily life status), psychological factors, antecedents of the harmful behavior, and triggers of the harmful behavior.

Our results suggest that background and situational factors form the background factors that lead to harmful behavior, that a disturbance in the harmony between these factors causes a disturbance in the psychological process, and that harmful behavior toward others is triggered by stimuli that leads to such behavior.

Considering that all the studies reviewed herein involved inpatients in medical settings, further research is required to identify the factors associated with harmful behaviors occurring in the community.

Author Contributions

I.K. and Y.S.: Study design. I.K., Y.K. and Y.F.: Literature search, collection of the literature, and data analysis. I.K.: Drafting of the manuscript. Y.K. and Y.S.: Supervision of the research. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI [grant number JP23K10224].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Anderson, K.K.; Jenson, C.E. Violence risk-assessment screening tools for acute care mental health settings: Literature review. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2019, 33, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaynes, B.N.; Brown, C.L.; Lux, L.J.; Brownley, K.A.; Van Dorn, R.A.; Edlund, M.J.; Coker-Schwimmer, E.; Weber, R.P.; Sheitman, B.; Zarzar, T.; et al. Preventing and de-escalating aggressive behavior among adult psychiatric patients: A systematic review of the evidence. Psychiatr. Serv. 2017, 68, 819–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, J. A review of effective interventions for reducing aggression and violence. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 2577–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saya, A.; Brugnoli, C.; Piazzi, G.; Liberato, D.; Di Ciaccia, G.; Niolu, C.; Siracusano, A. Criteria, procedures, and future prospects of involuntary treatment in psychiatry around the world: A narrative review. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Mellsop, G.; Brink, J.; Wang, X. Involuntary admission and treatment of patients with mental disorder. Neurosci. Bull. 2015, 31, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Translation, J.L. Act on Mental Health and Welfare for Persons with Mental Disorders or Disabilities. Available online: https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/ja/laws/view/4235 (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Bowers, L. Safewards: A new model of conflict and containment on psychiatric wards. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 21, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, M.C.; Andreyeva, E.; South, E.C.; MacDonald, J.M.; Branas, C.C. Neighborhood interventions to reduce violence. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2018, 39, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iozzino, L.; Ferrari, C.; Large, M.; Nielssen, O.; de Girolamo, G. Prevalence and risk factors of violence by psychiatric acute inpatients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, R.; Antenora, F.; Riba, M.; Belvederi Murri, M.; Biancosino, B.; Zerbinati, L.; Grassi, L. Aggressive behavior and psychiatric inpatients: A narrative review of the literature with a focus on the European experience. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2021, 23, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dack, C.; Ross, J.; Papadopoulos, C.; Stewart, D.; Bowers, L. A review and meta-analysis of the patient factors associated with psychiatric in-patient aggression. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2013, 127, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleissl-Muir, S.; Raymond, A.; Rahman, M.A. Incidence and factors associated with substance abuse and patient-related violence in the emergency department: A literature review. Australas. Emerg. Care 2018, 21, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tishler, C.L.; Reiss, N.S.; Dundas, J. The assessment and management of the violent patient in critical hospital settings. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2013, 35, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weltens, I.; Bak, M.; Verhagen, S.; Vandenberk, E.; Domen, P.; van Amelsvoort, T.; Drukker, M. Aggression on the psychiatric ward: Prevalence and risk factors. A systematic review of the literature. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, P.; Ashley, C. Violence and aggression: A literature review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2007, 14, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, S.; Smith, E.N.; Chang, Z.; Geddes, J.R. Risk factors for interpersonal violence: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 213, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, E.; Bader, S.; Evans, S.E. Situational variables related to aggression in institutional settings. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2013, 18, 792–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornaggia, C.M.; Beghi, M.; Pavone, F.; Barale, F. Aggression in psychiatry wards: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2011, 189, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrell-Berry, H.; Berry, K.; Bucci, S. The relationship between paranoia and aggression in psychosis: A systematic review. Schizophr. Res. 2016, 172, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, S.; Gulati, G.; Linsell, L.; Geddes, J.R.; Grann, M. Schizophrenia and violence: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazel, S.; Philipson, J.; Gardiner, L.; Merritt, R.; Grann, M. Neurological disorders and violence: A systematic review and meta-analysis with a focus on epilepsy and traumatic brain injury. J. Neurol. 2009, 256, 1591–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konttila, J.; Pesonen, H.M.; Kyngäs, H. Violence committed against nursing staff by patients in psychiatric outpatient settings. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 1592–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofthouse, R.; Golding, L.; Totsika, V.; Hastings, R.; Lindsay, W. How effective are risk assessments/measures for predicting future aggressive behaviour in adults with intellectual disabilities (ID): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 58, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reagu, S.; Jones, R.; Kumari, V.; Taylor, P.J. Angry affect and violence in the context of a psychotic illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Schizophr. Res. 2013, 146, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Akker, N.; Kroezen, M.; Wieland, J.; Pasma, A.; Wolkorte, R. Behavioural, psychiatric and psychosocial factors associated with aggressive behaviour in adults with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review and narrative analysis. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2021, 34, 327–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, K.; van Dorn, R.; Fazel, S. Risk factors for violence in psychosis: Systematic review and meta-regression analysis of 110 studies. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ettorre, G.; Pellicani, V. Workplace violence toward mental healthcare workers employed in psychiatric wards. Saf. Health Work. 2017, 8, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogonah, M.G.T.; Seyedsalehi, A.; Whiting, D.; Fazel, S. Violence risk assessment instruments in forensic psychiatric populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2023, 10, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.P.; Serper, M.; Reinharth, J.; Fazel, S. Structured assessment of violence risk in schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders: A systematic review of the validity, reliability, and item content of 10 available instruments. Schizophr. Bull. 2011, 37, 899–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Witt, K.; Xiang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Wang, X.; Fazel, S. Violence risk assessment in psychiatric patients in China: A systematic review. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2016, 50, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Castro, L.; Hoffman, K.; Cabello-Rangel, H.; Arredondo, A.; Herrera-Estrella, M. Family history of psychiatric disorders and clinical factors associated with a schizophrenia diagnosis. Inquiry 2021, 58, 469580211060797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, N.; Bergen, S.E. Environmental risk factors for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and their relationship to genetic risk: Current knowledge and future directions. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 686666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varese, F.; Smeets, F.; Drukker, M.; Lieverse, R.; Lataster, T.; Viechtbauer, W.; Read, J.; van Os, J.; Bentall, R.P. Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: A meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective- and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophr. Bull. 2012, 38, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kester, J.C.; Lilac, S.M.; Daddio, A.R.; Abraham, S.P. Interpersonal relationships in individuals struggling with mental illness. Hum. J. 2021, 20, 40–58. [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo, C.; Volpe, U.; Matanov, A.; Priebe, S.; Giacco, D. Social networks of patients with psychosis: A systematic review. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelwell, E.L.R.; Dunkerley, L.; Goodwin, R.; Giacco, D. Effectiveness of online social networking interventions on social isolation and quality of life of people with psychosis: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 339, 116088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J.; Brazier, J.; O’Cathain, A.; Lloyd-Jones, M.; Paisley, S. Quality of life of people with mental health problems: A synthesis of qualitative research. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2012, 10, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, T.; Leese, M.; Clarkson, P.; Taylor, R.E.; Turner, D.; Kleckham, J.; Thornicroft, G. Links between social network and quality of life: An epidemiologically representative study of psychotic patients in south London. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 1998, 33, 229–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, S.M.; Abdelraof, A.I.; El-Monshed, A.H.; Amr, M.; Elhay, E.S.A. Insight and empathy in schizophrenia: Impact on quality of life and symptom severity. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2024, 52, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanislaus, A. Assessment of dangerousness in clinical practice. Mo. Med. 2013, 110, 61–64. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).