Abstract

Objective: What types of multilevel interventions exist to improve blood pressure among community-dwelling adults aged 18+ in the United States? What is the treatment efficacy? Data Source: Peer-reviewed articles from Cochrane Library, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and PubMed. The search strategy was pre-registered on Open Science Framework. Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: Inclusion criteria were community-dwelling adults in the United States aged 18 or older; interventions involving at least two levels; at least one blood pressure outcome measured; and published in a peer-reviewed journal. Data Extraction: Intervention activities, blood pressure outcomes, and moderation/subgroup analyses, when available, were extracted. Data Synthesis: Qualitative synthesis and summary statistics. Results: Ninety-five papers covering 89 RCTs were included. Multilevel interventions involving the individual and healthcare team (without health policies = 49 studies; with health policies = 15 studies) tended to show the most consistent saltatory effects on blood pressure (systolic: 46% of studies showed statistical improvement; diastolic: 47% of studies showed statistical improvement). Interventions involving families or communities outside of healthcare settings were promising but were less frequently reported (19% of studies). Conclusions: There was mixed evidence that multilevel interventions targeting cardiovascular health improved blood pressure among U.S.-based adults. Future research should continue evaluating interventions that improve the individual as well as the environments in which individuals work and play, especially those levels outside of traditional healthcare settings.

1. Introduction

Despite population-level improvements in prevalence and control of hypertension among adults, disparities among subpopulations including non-Hispanic Black adults persist [1]. Current first-line treatments for elevated blood pressure (BP) and hypertension primarily involve individual lifestyle modifications such as diet and nutritional changes, physical activity, or weight loss [2]. While these treatments improve BP, there is limited evidence they reduce disparities or address social determinants of adoption/adherence of healthy lifestyle behaviors [3,4]. Multilevel interventions, or those affecting multiple levels of influence such as an individual and their healthcare provider [5], may outperform solely individual-based interventions for BP as they better account for one’s social or physical environment [6]. A multilevel approach may also reduce health disparities BP by intervening on larger structural factors (e.g., health policies). The last systematic review on blood pressure (BP) control interventions was published in 2018 and primarily focused on pharmacologic or team-based healthcare interventions. However, since then, there have been growing calls from organizations like the American Heart Association (AHA) to address upstream factors influencing BP, including stress and social determinants of health [7]. These upstream factors include social determinants such as housing insecurity, neighborhood conditions, food access, economic instability, chronic stress, and systemic racism [8,9,10,11]. While these are widely recognized as root causes of hypertension disparities, most interventions continue to emphasize individual behavior change. Our review extends the prior literature by including multilevel interventions across diverse domains—healthcare teams, families, communities, and health policies—which reflect the evolving landscape of BP management strategies. By incorporating studies before and after 2018, we comprehensively assess intervention effectiveness while identifying persistent gaps in addressing disparities in BP control, particularly among minoritized groups. In response to recent calls from the AHA to rigorously examine multilevel interventions with the greatest potential for reducing cardiovascular health disparities [12], we conducted a rapid review to answer the following:

- (1)

- What types of multilevel interventions exist to improve BP among community-dwelling adults aged 18 years+ in the United States (U.S.)?

- (2)

- What is the treatment efficacy on BP?

Where possible, we also described which study characteristics moderated intervention efficacy.

2. Methods

Our review followed Grant and Booth’s [13] approach to conducting a rapid review and was conducted in line with the reporting guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Appendix A.2) [14]. Methodological quality was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB) Tool version 2.0 for RCTs [15]. This tool evaluates five domains: (1) the randomization process, (2) deviations from intended interventions, (3) missing outcome data, (4) measurement of the outcome, and (5) selection of the reported result. Each domain was rated as “Low risk”, “Some concerns”, or “High risk”, and an overall risk of bias judgment was determined according to Cochrane guidance, typically reflecting the highest risk rating across domains. Study quality assessment was used to interpret results synthesized in this review and to guide the development of conclusions and future recommendations. Full item-level RoB scores, with reviewer justifications for each domain, are publicly available via the study’s Open Science Framework page: https://osf.io/9nhef.

Prior to executing database searches, we preregistered our protocol on Open Science Framework (OSF). An anonymized OSF page is available at: https://osf.io/hzsr6/?view_only=30b08c6976774136aefd04f70f14f8f0 (accessed on 1 February 2024).

3. Data Sources

An exhaustive search of 4 databases was conducted. Databases included were PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library (including Cochrane Reviews), and PsycINFO. The search strategy was piloted and refined following the advice of a medical librarian. Searches were conducted between 24 January and 2 February 2024. Search terms for each database are provided in Appendix A.1. Search terms were selected to reflect the following: (1) BP, hypertension, or CVD health assessed by the AHA’s Simple 7 or its updated version, the Essential 8 [16]; (2) multilevel interventions; and (3) adults aged 18 or older living in the U.S. Initial search results were downloaded into the Covidence software (https://support.covidence.org/help/how-can-i-cite-covidence, accessed on 1 February 2024) program to remove duplicates (Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org, accessed on 1 February 2024).

4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies. Studies were selected based on the following major inclusion criteria: (1) participants were community-dwelling adults aged 18 years or older based in the U.S.; (2) included a multilevel intervention evaluated in an RCT with an appropriate control group; (3) included at least one BP-related outcome; and was (4) published any time in a peer-reviewed journal. As this was a rapid rather than systematic review, interventions published in grey literature or in a non-English language were excluded.

In an intervention context, multilevel interventions are those that target at least two domains [5,6]. Informed by ecological frameworks that inform behavioral interventions, we categorized intervention activities into the following domains: (a) individuals, (b) family or other social supports; (c) healthcare teams (e.g., physician, pharmacist, nurse); (d) community environment (e.g., specific community stakeholders or physical environments themselves); or (e) health policies (e.g., decision support aids) [17,18]. In the literature, community health workers or promotores were frequently included as part of the intervention. We classified them as either belonging to the healthcare team or community environment, depending on which setting the community health workers/promotores conducted their intervention activities. See Table 1 for the major inclusion criteria and sample characteristics of the studies that were included in the current review.

Table 1.

Major inclusion criteria.

Studies were excluded for various reasons, even if they initially appeared to meet the inclusion criteria. For example, studies that included interventions targeting only one domain (e.g., individual-level interventions) were excluded, as they did not meet the multilevel intervention criterion. Additionally, some studies focused on populations outside of the U.S. or included individuals in institutional settings, which led to their exclusion. We also excluded studies where the intervention did not meet the definition of multilevel, such as those that did not integrate multiple intervention domains (e.g., individual and healthcare team or individual and community).

Participants. Interventions were eligible if their participants were community-dwelling adults in the U.S. aged 18 years+. By community-dwelling adults, we refer to those not living in institutionalized settings such as skilled nursing facilities, nursing homes, etc. This population represents a crucial focus for public health interventions, as they are likely to benefit from community-based resources and preventive strategies. Interventions targeting community-dwelling adults can also address upstream factors such as social support and stress that play key roles in blood pressure control, especially among underserved populations. Participants did not need a diagnosed BP-related health condition (e.g., elevated BP or a history of hypertension diagnosis from electronic medical records) for inclusion in this review. We included studies where participants did not necessarily have diagnosed BP-related conditions to capture interventions aimed at primary prevention. Many social and behavioral determinants, such as chronic stress and limited social support, contribute to elevated BP long before clinical diagnosis; including these studies allows for a broader understanding of intervention effectiveness across the continuum of BP risk, addressing both prevention and management. If studies included individuals under 18 (e.g., parent–child intervention), the study was eligible for inclusion, and only adult outcomes were reported.

Primary and secondary outcomes. For each included study, we extracted all reported blood pressure outcomes. This included in-office blood pressure measurements, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM), home blood pressure monitoring, clinical diagnosis of hypertension, and composite cardiovascular health scores where blood pressure was a component (such as Life’s Simple 7 or Life’s Essential 8). When studies reported multiple blood pressure outcomes, all eligible outcomes were extracted. Extracted effect measures included raw blood pressure values (reported as mean ± standard deviation when available), proportions of participants classified as hypertensive (based on study-defined criteria), and cardiovascular risk scores where blood pressure was embedded in composite measures (e.g., Life’s Simple 7 or Essential 8). Due to variation in how outcomes were reported across studies, results were summarized narratively and using descriptive statistics.

Other data items. In addition to blood pressure outcomes, we extracted study-level variables including the following: participant characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, and comorbidities); intervention characteristics (delivery setting, duration, intensity, target levels [individual, healthcare team, family, community, policy]); and reported subgroup or moderator analyses, when available. If data were unclear or not reported, assumptions were avoided, and missingness was noted in the extraction table.

5. Data Extraction

Searches were conducted, screened, and reviewed for inclusion according to the selection criteria by one author (A1). Data were extracted concurrently with the risk of bias (RoB) assessment by two authors (A1, A2). Rather than independently assessing all articles, the authors divided them for data extraction and RoB assessment and met regularly to adjudicate articles. Extracted data included overall sample size, intervention activities, intervention duration, comparison group(s), key eligibility criteria, and results (Table 2 and Table 3). Study-level RoB item scores are available via the study’s Open Science Framework page (https://osf.io/hzsr6/?view_only=30b08c6976774136aefd04f70f14f8f0, accessed on 1 February 2024). Missing or incomplete data were noted in the data extraction table, and no assumptions were made regarding these missing data. Studies with unclear or missing outcomes were excluded from relevant analyses, and such exclusions are detailed in Appendix A. Formal assessment of reporting bias (e.g., publication bias or selective outcome reporting) was not conducted, consistent with the narrative nature and methodological scope of this rapid review.

Table 2.

Study-level characteristics (N = 95 manuscripts reflecting 89 unique trials) and Total Risk of Bias Score.

Table 3.

Intervention activities and summary of results.

6. Data Synthesis

Findings from the included studies were synthesized using tables, summary statistics, and narrative summaries. Studies were grouped based on the intervention components: (1) individual and healthcare team; (2) individual and healthcare team and health policy; (3) individual and community environment; (4) individual and family/social support; and (5) combinations of these components, as described in the inclusion and exclusion criteria. This grouping allowed us to compare the effectiveness of different types of multilevel interventions on BP outcomes. Results from the included studies were summarized using tables (Table 2 and Table 3), which detail study characteristics, outcomes, and intervention types. In addition, summary statistics for blood pressure outcomes and moderator analyses were provided, accompanied by narrative synthesis to highlight key findings across intervention types.

As a rapid review, findings were synthesized using a narrative summary approach, which involved qualitative analysis and summary statistics to provide a descriptive overview of the results. Given the heterogeneity of the included studies (in terms of intervention types and outcomes), meta-analysis was not performed. The synthesis aimed to assess intervention effectiveness across different components and moderators, as detailed in Table 2 and Table 3.

We conducted subgroup analyses to examine the effect of baseline blood pressure on intervention effectiveness. These analyses were performed when studies provided data on baseline BP and were consistent with our review’s objectives. Given the narrative nature of this review, no formal statistical tests for heterogeneity were performed.

7. Results

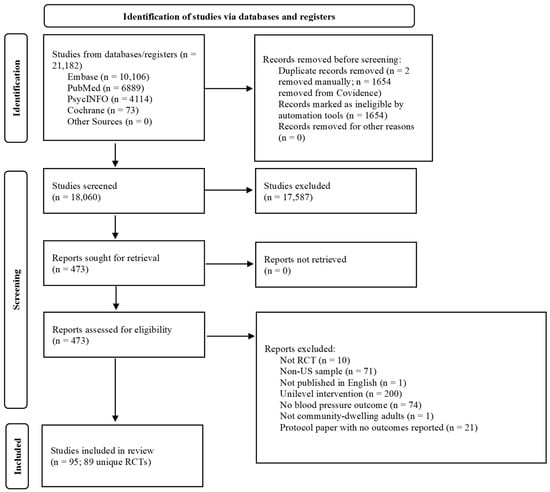

The PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1) shows the studies’ selection process. The literature search yielded 21,182 articles, of which 473 full-text articles were screened for eligibility. Ninety-five articles reporting on 89 multilevel interventions were ultimately included. All studies were randomized at either the individual or cluster level. All interventions were conducted in the U.S. with adults aged 18 or older (Table 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA study selection flow chart.

8. Sample Characteristics

The sample size of the included studies ranged from 35 to 10,698 participants distributed across 93 healthcare providers. There was marked heterogeneity across samples by race, gender, and study-specific eligibility criteria (e.g., eligibility depending on diagnosis of hypertension or Type 2 diabetes). Common participant-specific eligibility criteria across studies included the following: (1) the presence or absence of hypertension, CVD disease, type 2 diabetes, obesity, or participant is prescribed medication to treat these health conditions (e.g., antihypertensives); (2) elevated lab measures such BP or HbA1c; or (3) demonstrated poor BP control evinced through medication refill audits or insufficient medication intensification. Twenty-five of the 95 studies (26%; 22 RCTs and 2 follow-up manuscripts) included racial or ethnic identity as an inclusion criterion; this included Black (17%; 14 RCTs and 2 follow-up manuscripts) or South Asian (1%; 1 RCT) adults or those with Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity (7%; 7 RCTs). Overall, 6 of the 95 studies (6%; 4 RCTS and 2 follow-up manuscripts) were conducted only among men, and 3 studies (3%; 3 RCTs) were conducted only among women.

For cluster-randomized interventions, the inclusion criteria ranged but tended to include the following: (1) years or hours/week a physician sees patients; (2) a percentage of the site’s caseload or clientele meeting eligibility criteria (e.g., uncontrolled BP); or (3) the site serves a particular population (e.g., predominantly Black churches or barbershops).

9. General Characteristics of the Multilevel Interventions

Interventions varied in length from four weeks to five years. The most common intervention duration was 12 months (38 RCTs; 40%). Interventions were most often compared against (enhanced) usual care (67 studies; 70%). Other control group types included delayed intervention/waitlist, psychoeducation (e.g., receive pamphlet with Joint National Committee [JNC]-7 guidelines [114]), or low-intensity versions of the multilevel intervention, which may include individual intervention components in a factorial design or less intensive dose in a nonfactorial design.

Most studies had low RoB (67%; 60 RCTs, 3 follow-up papers, and 1 subgroup analysis), but a sizeable proportion also had some RoB concerns (31%; 29 RCTs and 1 follow-up paper). Only one study had high RoB.

In descending frequency, the types of multilevel interventions targeting BP outcomes were: (1) individual and healthcare team (47 RCTs and 2 follow-up papers); (2) individual and healthcare team and health policies (15 RCTs; no follow-up papers); (3) individual and community environment (9 RCTS; no follow-up papers); (4) individual and family/social support (6 RCTs and 1 follow-up paper); (5) individual and family/social support and healthcare team (4 RCTs; no follow-up papers); (6) healthcare team and health policies (3 RCTs; no follow-up papers); (7) individual and healthcare team and community environment (2 RCTs, 1 follow-up paper, and 1 subgroup analysis); (8) individual and community environment and health policies (2 RCTs; no follow-up papers); (9) individual and health policies (1 RCT; no follow-up papers), and (10) individual and family/social support and healthcare team and community environment (1 RCT, no follow-up papers). Notably, all but three RCTs [103,104,105] incorporated individual level intervention activities. Across the 89 randomized controlled trials included in this review, over half (53%) were published in 2018 or later, reflecting a relatively recent body of evidence. For readability, descriptions of intervention activities and outcomes are separated by intervention type. See Table 2 and Table 3 for additional details of intervention activities and outcomes. For a summary of multilevel interventions showing robust or sustained blood pressure improvements and population-specific effects, see Appendix A.3.

9.1. Individual and Healthcare Team (47 RCTs and 2 Follow-Ups)

Blood pressure outcomes. In total, 45 studies (43 RCTs and 2 follow-up papers) examined systolic BP as an outcome measure. Of those, 23 studies (51%; 21 RCTs and 2 follow-up papers) found significantly lower systolic BP among the intervention group.

Thirty-one studies (30 RCTs and 1 follow-up paper) examined diastolic BP as an outcome measure. Of those, 17 (55%; 16 RCTs and 1 follow-up paper) found significantly lower diastolic BP among the intervention group. Six studies (6 RCTs, no follow-ups) examined other BP outcomes reflecting adequate BP control at the individual or clinic level, of which half (3 RCTs; 50%) found significantly better BP outcomes among the intervention group. Including the 2 follow-up papers, 6 RCTs examined post-intervention maintenance effects. Five studies (80%) found that immediate post-intervention benefits were not sustained, and one found long-term but not immediate post-intervention improvement.

Moderators. Three studies examined whether intervention effects were dependent on one’s baseline BP values. In two studies (66%), the intervention was significantly more effective for those with higher baseline BP/less adequate BP control. In the third study, there was a larger, albeit statistically nonsignificant, improvement among participants with poorer baseline BP control. Age, gender, and which team member delivered the intervention were examined as moderators in only one study, so no strong conclusions can be drawn about their effect on intervention effectiveness.

9.2. Individual and Healthcare Team and Health Policy (15 RCTs and 0 Follow-Ups)

Blood pressure outcomes. Thirteen studies examined systolic BP as an outcome measure. Of those, 4 studies (31%) found significantly lower systolic BP among the intervention group. Three studies examined whether intervention effects on systolic BP were maintained; intervention effects were sustained in one study (33%). Seven studies examined diastolic BP as an outcome measure. Of those, one study (14%) found significantly lower diastolic BP among the intervention group. Four studies examined other BP outcomes, including medication refill adherence, physician clinical inertia, or percentage of patients with adequate BP control. Three studies (75%) found significantly better BP outcomes among the intervention group.

Moderators. One study examined whether the intervention significantly improved systolic BP when restricting analyses to those with baseline systolic BP ≤ 130. Like the full-sample analyses, there were no significant intervention effects. No other moderators were examined among these interventions.

9.3. Individual and Community Environment (9 RCTs and 0 Follow-Ups)

Blood pressure outcomes. All studies examined intervention effects on systolic BP, with significant intervention effects in two studies (22%). Improvements to systolic BP were not present in one study that also reported 12-month outcomes. All but one study examined intervention effects on diastolic BP, with significant intervention effects not sustained at 12 months in one study (12.5%). Two studies examined intervention effects on Life’s Simple 7 total scores, with significant intervention effects present in both.

Moderators. One study examined the moderating effect of age on total Life’s Simple 7 improvement and found significant intervention effects only among those participants under 60 years old.

9.4. Individual and Family (6 RCTs and 1 Follow-Up)

Blood pressure outcomes. Six RCTs (and 1 follow-up) examined intervention effects on systolic BP, and no significant intervention effects were found, nor did they occur at follow-up. Four RCTs (and 1 follow-up) assessed diastolic BP, where intervention effects were mixed. In one RCT, children but not parents had significantly improved diastolic BP. A second RCT (and 1 follow-up) demonstrated significantly improved diastolic BP for the care recipient’s partner only. This improvement was sustained only among those who received couples counseling. The remaining two studies did not find significantly improved diastolic BP. Additionally, one study assessed 30-year estimated systolic BP and found marginally significant improvement for the care recipient’s partner.

Moderators. Intervention effect moderators were not examined in these studies.

9.5. Individual and Family and Healthcare Team (4 RCTs and 0 Follow-Ups)

Blood pressure outcomes. All studies measured systolic BP, with mixed evidence of improvements among the intervention relative to control group (25% with improvement). Two studies measured diastolic BP and found mixed evidence for significant improvements in the intervention relative to control group (50% with improvement).

Moderators. Intervention effect moderators were not examined in these studies.

9.6. Healthcare Team and Health Policy (3 RCTs and 0 Follow-Ups)

Blood pressure outcomes. One study assessed systolic BP and found significant improvements in daytime, nighttime, and 24 h systolic BP in the intervention relative to control group. Two studies assessed the percentage of patients who had controlled BP; one found physician-level incentives, but not practice-level or combined physician-practice incentives resulted in greater BP control that was not sustained after an 18-month washout period. A second study found the intervention relative to control had more participants with controlled 24 h BP at immediate posttest. Lastly, one study assessed the percentage of patients who met target BP levels and found significantly greater BP control among intervention clinics.

Moderators. Intervention effect moderators were not examined in any study.

9.7. Individual and Healthcare Team and Community Environment (2 RCTs and 1 Follow-Up and 1 Subgroup Analysis)

Blood pressure outcomes. Both RCTs assessed immediate posttest systolic BP, where there was mixed evidence of the intervention such that there was significant improvement in one and marginal improvement in the other. For the RCT with significant immediate systolic BP changes, improvements were sustained at 12 months posttest. Both RCTs also assessed immediate posttest diastolic BP, where there was similarly mixed evidence of the intervention such that there was significant improvement in one and no improvement in the other. For the RCT with significant immediate diastolic BP changes, improvements were sustained at 12 months posttest.

Moderators. One study examined effects of the barber program among a subgroup of men with a baseline systolic BP ≥ 140 mmHg and found those whose barbers referred them to a hypertension specialist had significantly improved systolic BP compared to controls. There were no significant intervention effects among participants whose barbers referred them to primary care physicians.

9.8. Individual and Community Environment and Health Policies (2 RCTs and 0 Follow-Ups)

Blood pressure outcomes. Both studies examined the intervention effect on systolic BP, and neither study demonstrated significant improvement relative to controls. Both studies examined diastolic BP, but there were also no significant intervention effects for either relative to controls.

Moderators. One study restricted analyses to those with dysglycemia and found that the intervention effect on systolic BP was stronger, albeit statistically nonsignificant, compared to the full sample.

9.9. Individual and Health Policy (1 RCT and 0 Follow-Ups)

Blood pressure outcomes. Systolic BP improved similarly across intervention groups, but there were no between-group differences.

Moderators. Intervention effect moderators were not examined in this study.

9.10. Individual and Family and Healthcare Team and Community (1 RCT and 0 Follow-Ups)

Blood pressure outcomes and moderators. The BP outcomes reported were from when the children were assessed in their mid-30s. Men who received the program had significantly better systolic and diastolic BP compared to controls and were less likely to fall into the Stage I hypertension category. Women did not have significantly different BP values but were marginally less likely to be pre-hypertensive.

10. Discussion

Despite ongoing efforts to improve BP within the U.S., rates of uncontrolled BP and hypertension prevalence have increased in recent years [115,116]. Although interventions targeting individual-level CVD risk factors such as physical activity are promising therapeutic approaches, achieving optimal BP control involves a variety of individual, social, environmental, and healthcare system factors. We found overall, there was mixed evidence that multilevel interventions targeting such factors improved BP outcomes among community-dwelling adults in the U.S. Multilevel interventions involving the individual and healthcare team—either with or without health policy intervention components—tended to show the most consistent saltatory effects on BP, but emerging literature suggests multilevel interventions involving the community hold promise for improving BP as well. In addition to immediate posttest effects, only a minority of studies assessed outcomes beyond 12 months, and even fewer examined whether improvements were sustained following the active intervention period. Effects that were reported often diminished over time, supporting existing evidence that ongoing support and maintenance strategies are needed to preserve BP-reducing benefits. This underreporting of long-term and post-intervention outcomes limits our ability to draw conclusions about the durability of multilevel interventions and highlights the need for extended follow-up in future trials [15].

Almost all interventions included activities for the individual/patient to engage in and usually targeted traditional CVD risk factors such as smoking cessation, participating in fitness courses, or receiving BP self-monitoring psychoeducation and equipment. While individual-based lifestyle modification improves CVH, making these changes without comprehensive efforts to address the underlying social conditions that drive high-risk health behaviors is very difficult and may exacerbate existing inequities [117,118].

The multilevel interventions in this review attempt to address upstream factors as they occur within the healthcare setting (e.g., people or policies) or community. The healthcare team was frequently activated and involved collaborative care between members of a healthcare team and occurred within traditional healthcare settings. Teams typically included embedded physicians, pharmacists, and community health workers/promotores. The role of the community health worker was variable across interventions [19]; not only could they help patients navigate the healthcare system, but they also supported navigating patients’ local neighborhood facilities and resources. When healthcare policies were enacted, they typically involved electronic decision support aids, physician-level incentives for controlling their patients’ BP, or other incentive-related policies to promote health behaviors. Although less commonly applied, there were interventions involving people and places outside of a traditional healthcare setting, such as churches and barbershops, that primarily serve racially minoritized populations. Like community health workers, these individuals were typically community members trained on skills like delivering health information, discussing barriers and facilitators to achieving health, and facilitating resource linking/referrals for participants. Interventions involving family were also not commonly applied but show promise for having short-term benefits, as well as the potential to mitigate long-term CVH decline and health disparities across ages [118]. Together, interventions using these approaches provide models for establishing partnerships between traditional healthcare providers and individuals within the communities they serve. Notably, few studies rigorously evaluated policy-level interventions through randomized controlled trials, limiting our understanding of how systemic changes—such as insurance coverage expansion, clinician reimbursement models, or public health infrastructure investments—might interact with individual or healthcare team-level efforts to improve BP control.

These gaps in equity-focused analysis are further underscored by the limited exploration of treatment moderators across trials. While many interventions were conducted in racially minoritized populations, few explicitly tested whether effects varied by race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status. A small number of studies, such as Victor et al. [108,109] and Boulware et al. [27], were designed with equity as a central focus, yet subgroup analyses were uncommon. More rigorous attention to disparity reduction is needed in future multilevel trials, including both study design and analytic strategies that examine differential effects across social groups.

While multilevel interventions are promising avenues for health promotion, it is possible benefits are not similar across all participants. Few moderators of intervention effectiveness were examined among the reviewed studies, where we found promising evidence that multilevel interventions may be more effective for those with higher baseline BP. This partially replicates previous findings that lifestyle-based interventions may have differential treatment effects depending on one’s baseline health [20]. Compared to our findings, however, previous work suggests that pharmacologic interventions have similar CVD risk-reducing effects regardless of one’s baseline risk [21,22]. This discrepancy may be driven by some multilevel interventions addressing both upstream contributors to CVH and pharmacotherapy in tandem rather than pharmacotherapy alone. For example, healthcare workers may have improved patients’ self-empowerment around disease management and/or physician-patient communication, in turn improving patients’ treatment adherence and driving improved BP. As most interventions involved individual-level activities, it is possible those with poorer baseline BP had more treatment options and thus greater engagement with the intervention.

Although none of the interventions were explicitly designed for those with multiple chronic conditions, several interventions were conducted among those with type 2 diabetes, a condition with significantly overlapping risk factors with hypertension [23]. Compared to other disease management guidelines (e.g., Joint National Committee-8 for hypertension [24]; Kidney Disease-Improving Global Outcomes for chronic kidney disease [25]), the American Diabetes’ Association provides standards of care for those with comorbid hypertension [26]. Given the large proportion of Americans with multiple chronic health conditions [27], treating common underlying risk factors together rather than the separate health conditions may improve health outcomes and healthcare [28], especially for those with complex medical needs. Future research should develop, implement, and evaluate innovative models of care, such as multilevel interventions, to prevent and manage multiple chronic conditions [119].

Despite the promise of multilevel interventions, few studies reported formal economic evaluations, limiting our understanding of their scalability and sustainability. A small number of trials assessed cost-effectiveness or cost-related outcomes. For example, Wang et al. evaluated the economic impact of telephone-based self-management interventions for blood pressure control and found them to be cost-effective relative to usual care [81]. Similarly, the PEP4PA trial assessed both health outcomes and cost-effectiveness of a multilevel physical activity intervention in low-income older adults [32]. Additionally, Katon et al. conducted a cost-effectiveness analysis of a collaborative care intervention for patients with depression and poorly controlled diabetes and/or coronary heart disease, including hypertension, and found it to be cost-effective over a 24-month period [52]. However, the vast majority of trials did not report resource use or economic implications. This gap in the literature poses challenges for broader implementation, particularly in under-resourced settings. Future studies should integrate economic evaluations alongside clinical outcomes to better assess the value and feasibility of these interventions in real-world contexts.

Finally, attention should be drawn to the continued lack of rural community interventions for hypertension management. It is known that hypertension rates in rural areas are roughly 10% higher than urban areas [120]. Studies with community interventions included in this review did address the highest at-risk population for hypertension (non-Hispanic Black adults) but were generally located in urban community settings (e.g., churches and barbershops). While interventions were generally successful, future work should focus on implementation of these interventions in the rural setting. Hypertension intervention work has begun emphasizing underserved or resource-limited populations, but many studies are still situated in urban settings [121,122]. Recently, the AHA has identified the rural population as one that needs researchers’ attention [123]. Incorporating the findings of this review and the intervention strategies highlighted is imperative to improve hypertension management in this vulnerable population.

This review has several limitations. As a rapid review, we used streamlined methods to balance rigor and efficiency. While individual study risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane RoB 2.0 tool, we did not conduct a formal certainty of evidence appraisal (e.g., GRADE), which is consistent with the methodological scope of rapid reviews. A formal GRADE approach would have allowed for a more structured appraisal of overall confidence in the body of evidence and strength of recommendations. Additionally, the search was limited to peer-reviewed, English-language publications and U.S.-based samples, which may have excluded relevant studies. Future systematic reviews could expand on this work by incorporating such tools and broader inclusion criteria to evaluate the strength and certainty of evidence more comprehensively.

11. Conclusions

Multilevel interventions to improve BP among adults in the U.S. are markedly variable but predominantly involve the participant/patient and healthcare team. While these interventions show potential for improving health, it is not consistent across trials and remains unclear which combination(s) produce the most health benefits. Given the saltatory effects were not maintained, it is also important for researchers to consider the long-term sustainability of any multilevel intervention they develop. Additionally, most of the studies included in this review were conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic. This presents an important opportunity for future research to explore how multilevel interventions can be augmented to address challenges posed by the pandemic. For instance, technology-delivered components, such as telehealth or app-based interventions, may enhance accessibility and scalability while addressing barriers to in-person care. Understanding the effectiveness of these adaptations in diverse populations, particularly minoritized groups, could provide critical insights for improving BP control in the post-pandemic era. Lastly, future research should continue developing and evaluating interventions that improve both the individual and the social, physical, and structural environments in which they work and play.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception or development of the study or to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data. All authors drafted the manuscript, or critically revised the manuscript, and gave final approval of the version submitted for publication. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring integrity and accuracy. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was not required for this study since no human participants were included.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study. An Open Science Framework protocol was created and can be found here https://osf.io/hzsr6/?view_only=30b08c6976774136aefd04f70f14f8f0 (accessed on 1 February 2024).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Cecelia Vetter, our medical librarian who provided critical feedback on the search strategy protocol.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Search Terms by Database

| Database | Search Terms |

| Cochrane Library | “Hypertension” OR “blood pressure” AND “intervention” OR “trial” AND “adult” Additional filters: Content type = Cochrane reviews; trials No date restriction “Search Word Variations” selected Cochrane Group = Hypertension Note: This database was searched to identify whether a similar review has been undertaken. Relevant reviews will be used to conduct hand searches for additional articles, if available. |

| EMBASE | (‘hypertension’/exp OR hypertension OR ‘blood pressure’) AND (‘hairdresser’ OR ‘diet therapy’ OR exercise OR ‘health coaching’ OR ‘public health’ OR ‘prevention and control’ OR ‘lifestyle’) AND english:la AND adult AND ([controlled clinical trial]/lim OR [randomized controlled trial]/lim) AND ([adult]/lim OR [aged]/lim OR [middle aged]/lim OR [very elderly]/lim OR [young adult]/lim) AND ‘article’/it |

| PsycINFO | MA “hypertension” OR TX (blood pressure or hypertension or hypertension or htn or elevated blood pressure) AND TX multilevel intervention OR TX lifestyle intervention OR TX health coach OR MA barber* OR TX (diet or nutrition or food habit or eating habit or lifestyle or food) OR TX (exercise or physical fitness or physical activity or exercise therapy) OR TX community health Search Limiters: Peer reviewed, publication type: peer reviewed journal; English language; Language: English; Age Groups: Adulthood (18 yrs & older), Young Adulthood (18–29 Years), Thirties (30–39 yrs), Middle Age (40–64 yrs), Aged (65 yrs & older), Very Old (85 yrs & older); Population Group: Human; Methodology: CLINICAL TRIAL; Exclude dissertations Search Expanders: Apply related words; also search within full text of the articles; apply equivalent subjects Search Modes: Boolean/phrase |

| PubMed | ((adult[Filter] OR middleagedaged[Filter])) AND ((((Hypertension[MH] OR Blood Pressure[MH] or Cardiovascular Health[MH]) OR (“Life’s Simple 7”[tw] or “Life’s Simple Seven”[tw] OR “Essential 8”[tw] OR “systolic”[tw] or “diastolic”[tw])) AND (Antihypertensive Agents/therapeutic use*[mh] OR Barbering*[MH] OR Cardiovascular Diseases/prevention & control [MH] OR Preventive Health Services [MH] OR Health Promotion/methods* [MH] OR “barber*”[tw] OR “salon”[tw] OR “health coach*”[tw] OR “Exercis*”[tw] OR “diet*”[tw] OR “lifestyle”[tw] OR “life style”[tw] OR “life-style”[tw] OR “nontraditional health care”[tw] or “multilevel”[tw] OR “multi-level”[tw] OR “communit*”[tw] AND clinical trial[publication type] or random*[title/abstract])) AND (“intervention”)) Note: * indicates wildcard term |

Appendix A.2. PRISMA Checklist

| Section and Topic | Item # | Checklist Item | Location Where Item Is Reported |

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | 1 |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist. | 2 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. | 5 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | 5 |

| METHODS | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses. | 6–7 |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organizations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. | 6 |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used. | Appendix A.1 (p. 26) |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 6–8 |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 7–9 |

| Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g., for all measures, timepoints, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. | 7–8 |

| 10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g., participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. | 8 | |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 8 |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g., risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results. | 8 |

| Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g., tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)). | 10–11 |

| 13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions. | 8 | |

| 13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses. | 8 | |

| 13d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used. | 9 | |

| 13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g., subgroup analysis, meta-regression). | 9 | |

| 13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results. | NA | |

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). | 8 |

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. | NA |

| RESULTS | |||

| Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram. | 27 (Figure 1) |

| 16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. | 7 | |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics. | 9–11 |

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study. | 29–41 (Table 2) |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots. | 42–65 (Table 3) |

| Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarize the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. | 9–14 |

| 20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was performed, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. | NA | |

| 20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. | NA | |

| 20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. | NA | |

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. | NA |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. | NA |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. | 15–18 |

| 23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review. | 16–17 | |

| 23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. | 17 | |

| 23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. | 18 | |

| OTHER INFORMATION | |||

| Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered. | 6 |

| 24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. | 6 | |

| 24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. | 6 (OSF preregistration link) | |

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review. | 2 |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors. | 1 |

| Availability of data, code and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review. | 2, 6, 8 |

From: [124]. This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ (accessed on 1 February 2024).

Appendix A.3. Summary of Multilevel Interventions with Notable BP Outcomes and Population-Specific Effects

| Study (First Author, Year) | Intervention Levels | Population Highlights | BP Outcome | Sustained Effects? | Notable Moderators/Subgroups |

| Ard, 2017 [83] | Individual and Community Environment | Black women aged 30–70 | ↓ SBP and DBP in both groups (significant within-group reductions) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Boulware, 2020 [27] | Individual and Healthcare Team | Black adults with uncontrolled hypertension | ↓ SBP among all groups (no intervention effect) | No (not sustained beyond intervention) | Not reported |

| Crist, 2022 [32] | Individual and Healthcare Team and Health Policies | Adults aged 50+ who walk without assistance; senior/community centers serving low-income populations | ↓ SBP (significant at 18 months); ↑ cost-effectiveness | No (not sustained at 24 months) | Not reported |

| Katon, 2010, 2012 [51,52] | Individual and Healthcare Team | Participants with diagnosis of diabetes and/or coronary heart disease | ↓ SBP (significant) | No (Not sustained at 18- or 24-month follow-up) | Not reported |

| Petersen, 2013 [103] | Healthcare Team and Health Policies | Physicians who see adult patients in hospital-based settings | ↑ BP control (via provider incentives) | Mixed (effect of individual-level incentives not sustained after 18-month washout) | Not reported |

| Svarstad, 2013 [76] | Individual and Healthcare Team and Health Policies | Black adults, 576 participants across 28 chain pharmacies | ↓ SBP (significant); ↑ BP control; ↑ adherence | Partial (SBP and adherence sustained at 12 months, but not BP control) | Not reported |

| Victor, 2018, 2019 [108,109] | Individual and Healthcare Team and Community | Black men, barbershop-based | ↓ SBP and DBP (significant) | Yes (12-month maintenance) | Greater effect among men with SBP ≥ 140 mmHg referred to hypertension specialists |

Note: SBP = systolic blood pressure; ↑ = increased/higher value; ↓ = decreased/lower value. This table highlights illustrative examples of interventions from the review that demonstrated statistically significant reductions in systolic and/or diastolic blood pressure, sustained effects over time, and/or subgroup differences in effectiveness. It is not an exhaustive list but intended to support interpretability by summarizing promising intervention characteristics and contexts.

References

- Dorans, K.S.; Mills, K.T.; He, J. Trends in prevalence and control of hypertension according to the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Guideline. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e008888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, R.M.; Moran, A.E.; Whelton, P.K. Treatment of hypertension: A review. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2022, 328, 1849–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimando, M. Perceived barriers to and facilitators of hypertension management among underserved African American older adults. Ethn. Dis. 2015, 25, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettey, C.M.; McSweeney, J.C.; Stewart, K.E.; Cleves, M.A.; Price, E.T.; Heo, S.; Souder, E. African Americans’ perceptions of adherence to medications and lifestyle changes prescribed to treat hypertension. SAGE Open 2016, 6, 2158244015623595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Owen, N.; Fisher, E.B. Ecological models of health behavior. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice; Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K., Viswanath, K., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 465–486. [Google Scholar]

- Paskett, E.; Thompson, B.; Ammerman, A.S.; Ortega, A.N.; Marsteller, J.; Richardson, D. Multilevel interventions to address health disparities show promise in improving population health. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 1429–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Baumer, Y.; Baah, F.O.; Baez, A.S.; Farmer, N.; Mahlobo, C.T.; Pita, M.A.; Potharaju, K.A.; Tamura, K.; Wallen, G.R. Social determinants of cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 2022, 130, 782–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havranek, E.P.; Mujahid, M.S.; Barr, D.A.; Blair, I.V.; Cohen, M.S.; Cruz-Flores, S.; Davey-Smith, G.; Dennison-Himmelfarb, C.R.; Lauer, M.S.; Lockwood, D.W.; et al. Social determinants of risk and outcomes for cardiovascular disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015, 132, 873–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braveman, P.; Gottlieb, L. The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014, 129, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Costa, M.V.; Odumlani, A.O.; Mohammed, S.A. Moving upstream: How interventions that address the social determinants of health can improve health and reduce disparities. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2008, 14, S8–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.J.; Muntner, P.; Alonso, A.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Carson, A.P.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Chang, A.R.; Cheng, S.; Das, S.R.; et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2019 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 139, e56–e528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moise, N.; Cené, C.W.; Tabak, R.G.; Young, D.R.; Mills, K.T.; Essien, U.R.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Lopez-Jimenez, F. Leveraging implementation science for cardiovascular health equity: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 146, e260–e278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altmann, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, 14898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Allen, N.B.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Black, T.; Brewer, L.C.; Foraker, R.E.; Grandner, M.A.; Lavretsky, H.; Perak, A.M.; Sharma, G.; et al. Life’s Essential 8: Updating and enhancing the American Heart Association’s construct of cardiovascular health: A presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 146, e18–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, E.B.; Brownson, C.A.; O’Toole, M.L.; Shetty, G.; Anwuri, V.V.; Glasgow, R.E. Ecological approaches to self-management: The case of diabetes. Am. J. Health Promot. 2005, 95, 1523–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adair, R.; Wholey, D.R.; Christianson, J.; White, K.M.; Britt, H.; Lee, S. Improving chronic disease care by adding laypersons to the primary care team: A parallel randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 159, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.K.; Dennison-Himmelfarb, C.R.; Szanton, S.L.; Bone, L.; Hill, M.N.; Levine, D.M.; West, M.; Barlow, A.; Lewis-Boyer, L.; Donnelly-Strozzo, M.; et al. Community Outreach and Cardiovascular Health (COACH) Trial: A randomized, controlled trial of nurse practitioner/community health worker cardiovascular disease risk reduction in urban community health centers. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2011, 4, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderegg, M.D.; Gums, T.H.; Uribe, L.; MacLaughlin, E.J.; Hoehns, J.; Bazaldua, O.V.; Ives, T.J.; Hahn, D.L.; Coffey, C.S.; Carter, B.L. Pharmacist intervention for blood pressure control in patients with diabetes and/or chronic kidney disease. Pharmacotherapy 2018, 38, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogden, P.E.; Abbott, R.D.; Williamson, P.; Onopa, J.K.; Koontz, L.M. Comparing standard care with a physician and pharmacist team approach for uncontrolled hypertension. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1998, 13, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogner, H.R.; de Vries, H.F. Integration of depression and hypertension treatment: A pilot, randomized controlled trial. Ann. Fam. Med. 2008, 6, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogner, H.R.; de Vries, H.F.; Kaye, E.M.; Morales, K.H. Pilot trial of a licensed practical nurse intervention for hypertension and depression. Fam. Med. 2013, 45, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bosworth, H.B.; Olsen, M.K.; Dudley, T.; Orr, M.; Goldstein, M.K.; Datta, S.K.; McCant, F.; Gentry, P.; Simel, D.L.; Oddone, E.Z. Patient education and provider decision support to control blood pressure in primary care: A cluster randomized trial. Am. Heart J. 2009, 157, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, H.B.; Olsen, M.K.; McCant, F.; Stechuchak, K.M.; Danus, S.; Crowley, M.J.; Goldstein, K.M.; Zullig, L.L.; Oddone, E.Z. Telemedicine cardiovascular risk reduction in veterans: The CITIES trial. Am. Heart J. 2018, 199, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulware, L.E.; Ephraim, P.L.; Hill-Briggs, F.; Roter, D.L.; Bone, L.R.; Wolff, J.L.; Lewis-Boyer, L.P.; Levine, D.M.; Greer, R.C.; Crews, D.C.; et al. Hypertension self-management in socially disadvantaged African Americans: The Achieving Blood Pressure Control Together (ACT) randomized comparative effectiveness trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasquillo, O.; Lebron, C.; Alonzo, Y.; Li, H.; Chang, A.; Kenya, S. Effect of a community health worker intervention among Latinos with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, E.M.; Cunningham, W.E.; Towfighi, A.; Sanossian, N.; Bryg, R.J.; Anderson, T.L.; Barry, F.; Douglas, S.M.; Hudson, L.; Ayala-Rivera, M.; et al. Efficacy of a chronic care-based intervention on secondary stroke prevention among vulnerable stroke survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2018, 11, e003228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwastiak, L.A.; Luongo, M.; Russo, J.; Johnson, L.; Lowe, J.M.; Hoffman, G.; McDonell, M.G.; Wisse, B. Use of a mental health center collaborative care team to improve diabetes care and outcomes for patients with psychosis. Psychiatr. Serv. 2018, 69, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, L.A.; Roter, D.L.; Carson, K.A.; Bone, L.R.; Larson, S.M.; Miller, E.R., 3rd; Barr, M.S.; Levine, D.M. A randomized trial to improve patient-centered care and hypertension control in underserved primary care patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011, 26, 1297–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crist, K.; Full, K.M.; Linke, S.; Tuz-Zahra, F.; Bolling, K.; Lewars, B.; Liu, C.; Shi, Y.; Rosenberg, D.; Jankowska, M.; et al. Health effects and cost-effectiveness of a multilevel physical activity intervention in low-income older adults: Results from the PEP4PA cluster randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowley, M.J.; Powers, B.J.; Olsen, M.K.; Grubber, J.M.; Koropchak, C.; Rose, C.M.; Gentry, P.; Bowlby, L.; Trujillo, G.; Maciejewski, M.L.; et al. The Cholesterol, Hypertension, And Glucose Education (CHANGE) study: Results from a randomized controlled trial in African Americans with diabetes. Am. Heart J. 2013, 166, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, M.J.; Edelman, D.; McAndrew, A.T.; Kistler, S.; Danus, S.; Webb, J.A.; Zanga, J.; Sanders, L.L.; Coffman, C.J.; Jackson, G.L.; et al. Practical telemedicine for veterans with persistently poor diabetes control: A randomized pilot trial. Telemed. J. E-Health 2016, 22, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daumit, G.L.; Dalcin, A.T.; Dickerson, F.B.; Miller, E.R.; Evins, A.E.; Cather, C.; Jerome, G.J.; Young, D.R.; Charleston, J.B.; Gennusa, J.V., 3rd; et al. Effect of a comprehensive cardiovascular risk reduction intervention in persons with serious mental illness: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e207247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Rosa, M.; Pitts, S.; Chen, P.H. An interprofessional collaboration of care to improve clinical outcomes for patients with diabetes. J. Interprof. Care 2020, 34, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennison, C.R.; Post, W.S.; Kim, M.T.; Bone, L.R.; Cohen, D.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Rame, J.E.; Roary, M.C.; Levine, D.M.; Hill, M.N. Underserved urban African American men: Hypertension trial outcomes and mortality during 5 years. Am. J. Hypertens. 2007, 20, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.N.; Han, H.R.; Dennison, C.R.; Kim, M.T.; Roary, M.C.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Bone, L.R.; Levine, D.M.; Post, W.S. Hypertension care and control in underserved urban African American men: Behavioral and physiologic outcomes at 36 months. Am. J. Hypertens. 2003, 16, 906–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emery-Tiburcio, E.E.; Rothschild, S.K.; Avery, E.F.; Wang, Y.; Mack, L.; Golden, R.L.; Holmgreen, L.; Hobfoll, S.; Richardson, D.; Powell, L.H. BRIGHTEN Heart intervention for depression in minority older adults: Randomized controlled trial. Health Psychol. 2019, 38, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, P.H.; McDonald, M.V.; Barrón, Y.; Gerber, L.M.; Peng, T.R. Home-based interventions for Black patients with uncontrolled hypertension: A cluster randomized controlled trial. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2016, 5, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbay, R.A.; Lendel, I.; Saleem, T.M.; Shaeffer, G.; Adelman, A.M.; Mauger, D.T.; Collins, M.; Polomano, R.C. Nurse case management improves blood pressure, emotional distress and diabetes complication screening. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2006, 71, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbay, R.A.; Añel-Tiangco, R.M.; Dellasega, C.; Mauger, D.T.; Adelman, A.; Van Horn, D.H. Diabetes nurse case management and motivational interviewing for change (DYNAMIC): Results of a 2-year randomized controlled pragmatic trial. J. Diabetes 2013, 5, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gary, T.L.; Bone, L.R.; Hill, M.N.; Levine, D.M.; McGuire, M.; Saudek, C.; Brancati, F.L. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of nurse case manager and community health worker interventions on risk factors for diabetes-related complications in urban African Americans. Prev. Med. 2003, 37, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, B.B.; Anderson, M.L.; Cook, A.J.; Catz, S.; Fishman, P.A.; McClure, J.B.; Reid, R.J. e-Care for heart wellness: A feasibility trial to decrease blood pressure and cardiovascular risk. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 46, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heisler, M.; Hofer, T.P.; Schmittdiel, J.A.; Selby, J.V.; Klamerus, M.L.; Bosworth, H.B.; Bermann, M.; Kerr, E.A. Improving blood pressure control through a clinical pharmacist outreach program in patients with diabetes mellitus in 2 high-performing health systems: The adherence and intensification of medications cluster randomized, controlled pragmatic trial. Circulation 2012, 125, 2863–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, S.; Leonard, C.E.; Yang, W.; Kimmel, S.E.; Townsend, R.R.; Wasserstein, A.G.; Ten Have, T.R.; Bilker, W.B. Effectiveness of a two-part educational intervention to improve hypertension control: A cluster-randomized trial. Pharmacotherapy 2006, 26, 1342–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiss, R.G.; Armbruster, B.A.; Gillard, M.L.; McClure, L.A. Nurse care manager collaboration with community-based physicians providing diabetes care: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Educ. 2007, 33, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.S.; Siemienczuk, J.; Pape, G.; Rozenfeld, Y.; MacKay, J.; LeBlanc, B.H.; Touchette, D. A randomized controlled trial of team-based care: Impact of physician-pharmacist collaboration on uncontrolled hypertension. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 23, 1966–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.S.; Wyatt, L.C.; Ali, S.H.; Zanowiak, J.M.; Mohaimin, S.; Goldfeld, K.; Lopez, P.; Kumar, R.; Beane, S.; Thorpe, L.E.; et al. Integrating community health workers into community-based primary care practice settings to improve blood pressure control among South Asian immigrants in New York City: Results from a randomized control trial. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2023, 16, e009321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangovi, S.; Mitra, N.; Grande, D.; Huo, H.; Smith, R.A.; Long, J.A. Community health worker support for disadvantaged patients with multiple chronic diseases: A randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 1660–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katon, W.J.; Lin, E.H.B.; Korff, M.V.; Ciechanowski, P.; Ludman, E.J.; Young, B.; Peterson, D.; Rutter, C.M.; McGregor, M.; McCulloch, D. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katon, W.; Russo, J.; Lin, E.H.; Schmittdiel, J.; Ciechanowski, P.; Ludman, E.; Peterson, D.; Young, B.; Von Korff, M. Cost-effectiveness of a multicondition collaborative care intervention: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2012, 69, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilbourne, A.M.; Goodrich, D.E.; Lai, Z.; Post, E.P.; Schumacher, K.; Nord, K.M.; Bramlet, M.; Chermack, S.; Bialy, D.; Bauer, M.S. Randomized controlled trial to assess reduction of cardiovascular disease risk in patients with bipolar disorder: The Self-Management Addressing Heart Risk Trial (SMAHRT). J. Clin. Psychiatry 2013, 74, e655–e662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krein, S.L.; Klamerus, M.L.; Vijan, S.; Lee, J.L.; Fitzgerald, J.T.; Pawlow, A.; Reeves, P.; Hayward, R.A. Case management for patients with poorly controlled diabetes: A randomized trial. Am. J. Med. 2004, 116, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, E.H.; Von Korff, M.; Peterson, D.; Ludman, E.J.; Ciechanowski, P.; Katon, W. Population targeting and durability of multimorbidity collaborative care management. Am. J. Manag. Care 2014, 20, 887–895. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Berra, K.; Haskell, W.L.; Klieman, L.; Hyde, S.; Smith, M.W.; Xiao, L.; Stafford, R.S. Case management to reduce cardiovascular risk in a county healthcare system. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 1988–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, K.L.; Asche, S.E.; Dehmer, S.P.; Bergdall, A.R.; Green, B.B.; Sperl-Hillen, J.M.; Nyboer, R.A.; Pawloski, P.A.; Maciosek, M.V.; Trower, N.K.; et al. Long-term outcomes of the effects of home blood pressure telemonitoring and pharmacist management on blood pressure among adults with uncontrolled hypertension: Follow-up of a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e181617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, K.L.; Bergdall, A.R.; Crain, A.L.; Jaka, M.M.; Anderson, J.P.; Solberg, L.I.; Sperl-Hillen, J.; Beran, M.; Green, B.B.; Haugen, P.; et al. Comparing pharmacist-led telehealth care and clinic-based care for uncontrolled high blood pressure: The Hyperlink 3 pragmatic cluster-randomized trial. Hypertension 2022, 79, 2708–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClintock, H.F.; Bogner, H.R. Incorporating patients’ social determinants of health into hypertension and depression care: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Community Ment. Health J. 2017, 53, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Huynh, M.N.; Young, J.D.; Ovbiagele, B.; Alexander, J.G.; Alexeeff, S.; Lee, C.; Blick, N.; Caan, B.J.; Go, A.S.; Sidney, S. Effect of lifestyle coaching or enhanced pharmacotherapy on blood pressure control among Black adults with persistent uncontrolled hypertension: A cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2212397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planas, L.G.; Crosby, K.M.; Farmer, K.C.; Harrison, D.L. Evaluation of a diabetes management program using selected HEDIS measures. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2012, 52, e130–e138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prezio, E.A.; Cheng, D.; Balasubramanian, B.A.; Shuval, K.; Kendzor, D.E.; Culica, D. Community Diabetes Education (CoDE) for uninsured Mexican Americans: A randomized controlled trial of a culturally tailored diabetes education and management program led by a community health worker. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2013, 100, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosas, L.G.; Thiyagarajan, S.; Goldstein, B.A.; Drieling, R.L.; Romero, P.P.; Ma, J.; Yank, V.; Stafford, R.S. The effectiveness of two community-based weight loss strategies among obese, low-income US Latinos. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 537–550.e532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.M.; Boyd, S.T.; Stephan, M.; Augustine, S.C.; Reardon, T.P. Outcomes of pharmacist-managed diabetes care services in a community health center. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2006, 63, 2116–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, E.M.; Johnston, C.A.; Cardenas, V.J.; Moreno, J.P.; Foreyt, J.P. Integrating CHWs as part of the team leading diabetes group visits: A randomized controlled feasibility study. Diabetes Educ. 2017, 43, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Korff, M.; Katon, W.J.; Lin, E.H.; Ciechanowski, P.; Peterson, D.; Ludman, E.J.; Young, B.; Rutter, C.M. Functional outcomes of multi-condition collaborative care and successful ageing: Results of randomised trial. BMJ 2011, 343, d6612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zillich, A.J.; Sutherland, J.M.; Kumbera, P.A.; Carter, B.L. Hypertension outcomes through blood pressure monitoring and evaluation by pharmacists (HOME study). J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2005, 20, 1091–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtrop, J.S.; Luo, Z.; Piatt, G.; Green, L.A.; Chen, Q.; Piette, J. Diabetic and obese patient clinical outcomes improve during a care management implementation in primary care. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2017, 8, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huebschmann, A.G.; Mizrahi, T.; Soenksen, A.; Beaty, B.L.; Denberg, T.D. Reducing clinical inertia in hypertension treatment: A pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2012, 14, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.D.; Harris, L.E.; Overhage, J.M.; Zhou, X.H.; Eckert, G.J.; Smith, F.E.; Buchanan, N.N.; Wolinsky, F.D.; McDonald, C.J.; Tierney, W.M. Failure of computerized treatment suggestions to improve health outcomes of outpatients with uncomplicated hypertension: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy 2004, 24, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatt, G.A.; Anderson, R.M.; Brooks, M.M.; Songer, T.; Siminerio, L.M.; Korytkowski, M.M.; Zgibor, J.C. 3-year follow-up of clinical and behavioral improvements following a multifaceted diabetes care intervention: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Educ. 2010, 36, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralston, J.D.; Hirsch, I.B.; Hoath, J.; Mullen, M.; Cheadle, A.; Goldberg, H.I. Web-based collaborative care for type 2 diabetes: A pilot randomized trial. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, R.L.; Malone, R.; Bryant, B.; Shintani, A.K.; Crigler, B.; Dewalt, D.A.; Dittus, R.S.; Weinberger, M.; Pignone, M.P. A randomized trial of a primary care-based disease management program to improve cardiovascular risk factors and glycated hemoglobin levels in patients with diabetes. Am. J. Med. 2005, 118, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roumie, C.L.; Elasy, T.A.; Greevy, R.; Griffin, M.R.; Liu, X.; Stone, W.J.; Wallston, K.A.; Dittus, R.S.; Alvarez, V.; Cobb, J.; et al. Improving blood pressure control through provider education, provider alerts, and patient education: A cluster randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 145, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenthaler, A.; de la Calle, F.; Pitaro, M.; Lum, A.; Chaplin, W.; Mogavero, J.; Rosal, M.C. A systems-level approach to improving medication adherence in hypertensive Latinos: A randomized controlled trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svarstad, B.L.; Kotchen, J.M.; Shireman, T.I.; Brown, R.L.; Crawford, S.Y.; Mount, J.K.; Palmer, P.A.; Vivian, E.M.; Wilson, D.A. Improving refill adherence and hypertension control in Black patients: Wisconsin TEAM trial. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2013, 53, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svetkey, L.P.; Pollak, K.I.; Yancy, W.S., Jr.; Dolor, R.J.; Batch, B.C.; Samsa, G.; Matchar, D.B.; Lin, P.H. Hypertension improvement project: Randomized trial of quality improvement for physicians and lifestyle modification for patients. Hypertension 2009, 54, 1226–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talavera, G.A.; Castañeda, S.F.; Mendoza, P.M.; Lopez-Gurrola, M.; Roesch, S.; Pichardo, M.S.; Garcia, M.L.; Muñoz, F.; Gallo, L.C. Latinos understanding the need for adherence in diabetes (LUNA-D): A randomized controlled trial of an integrated team-based care intervention among Latinos with diabetes. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 1665–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towfighi, A.; Cheng, E.M.; Ayala-Rivera, M.; Barry, F.; McCreath, H.; Ganz, D.A.; Lee, M.L.; Sanossian, N.; Mehta, B.; Dutta, T.; et al. Effect of a coordinated community and chronic care model team intervention vs usual care on systolic blood pressure in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2036227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinicor, F.; Cohen, S.J.; Mazzuca, S.A.; Moorman, N.; Wheeler, M.; Kuebler, T.; Swanson, S.; Ours, P.; Fineberg, S.E.; Gordon, E.E. DIABEDS: A randomized trial of the effects of physician and/or patient education on diabetes patient outcomes. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, V.; Smith, V.A.; Bosworth, H.B.; Oddone, E.Z.; Olsen, M.K.; McCant, F.; Powers, B.J.; Van Houtven, C.H. Economic evaluation of telephone self-management interventions for blood pressure control. Am. Heart J. 2012, 163, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, G.; Allen, N.A.; Zagarins, S.E.; Stamp, K.D.; Bursell, S.E.; Kedziora, R.J. Comprehensive diabetes management program for poorly controlled Hispanic type 2 patients at a community health center. Diabetes Educ. 2011, 37, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ard, J.D.; Carson, T.L.; Shikany, J.M.; Li, Y.; Hardy, C.M.; Robinson, J.C.; Williams, A.G.; Baskin, M.L. Weight loss and improved metabolic outcomes amongst rural African American women in the Deep South: Six-month outcomes from a community-based randomized trial. J. Intern. Med. 2017, 282, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, L.C.; Jenkins, S.; Hayes, S.N.; Kumbamu, A.; Jones, C.; Burke, L.E.; Cooper, L.A.; Patten, C.A. Community-based, cluster-randomized pilot trial of a cardiovascular mobile health intervention: Preliminary findings of the FAITH! trial. Circulation 2022, 146, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.L.; Conley, K.M.; Sánchez, B.N.; Resnicow, K.; Cowdery, J.E.; Sais, E.; Murphy, J.; Skolarus, L.E.; Lisabeth, L.D.; Morgenstern, L.B. A multicomponent behavioral intervention to reduce stroke risk factor behaviors: The stroke health and risk education cluster-randomized controlled trial. Stroke 2015, 46, 2861–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derose, K.P.; Williams, M.V.; Flórez, K.R.; Griffin, B.A.; Payán, D.D.; Seelam, R.; Branch, C.A.; Hawes-Dawson, J.; Mata, M.A.; Whitley, M.D.; et al. Eat, Pray, Move: A pilot cluster randomized controlled trial of a multilevel church-based intervention to address obesity among African Americans and Latinos. Am. J. Health Promot. 2019, 33, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.; Rosenberg, D.; Millstein, R.A.; Bolling, K.; Crist, K.; Takemoto, M.; Godbole, S.; Moran, K.; Natarajan, L.; Castro-Sweet, C.; et al. Cluster randomized controlled trial of a multilevel physical activity intervention for older adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nafziger, A.N.; Erb, T.A.; Jenkins, P.L.; Lewis, C.; Pearson, T.A. The Otsego-Schoharie healthy heart program: Prevention of cardiovascular disease in the rural US. Scand. J. Public Health Suppl. 2001, 56, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]