Abstract

Background: Perinatal depression and anxiety can be experienced simultaneously and change over time. This study aimed to explore the independent and joint developmental trajectories and predictors of perinatal depression and anxiety. Methods: From January 2022 to December 2023, a total of 1062 pregnant women from Affiliated Women’s Hospital of Jiangnan University were surveyed for depression and anxiety symptoms using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) in early pregnancy (T1, 0–13+6 weeks), mid-term pregnancy (T2, 14–27+6 weeks), late pregnancy (T3, 28–41 weeks), and 42 days postpartum (T4). Parallel-process latent class growth model (PPLCGM) was performed to identify the joint developmental trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety, and logistic regression was used to analyze factors of joint trajectories. Results: Perinatal depression and anxiety each showed four heterogeneous developmental trajectories, and three joint developmental trajectories were identified: “high–slightly decreasing depression and high decreasing anxiety group” (3%), “low–stable depression and low–stable anxiety group” (71%), and “moderate–slightly increasing depression and moderate–decreasing anxiety group” (26%). Adverse maternal history, history of anxiety and depression, and work stress were risk factors for the joint developmental trajectory of perinatal depression and anxiety, while regular exercise, paid work and social support were protective factors. Conclusions: Three joint developmental trajectories for perinatal depression and anxiety were identified, demonstrating group heterogeneity. Perinatal healthcare providers should pay attention to the mental health history of pregnant women, conduct multiple assessments of perinatal anxiety and depression, prioritize individuals with risk factors, and advocate for regular exercise, work participation, and provide greater social support.

1. Introduction

Perinatal depression and anxiety are very common globally, with prevalence rates as high as 5–30% [1,2,3]. If perinatal depression and anxiety are not treated promptly, they not only affect one’s physical and mental health and lead to adverse pregnancy outcomes, including spontaneous abortion, pre-eclampsia, cesarean section, preterm birth, and low birth weight [4,5,6], but also have long-term effects on the cognitive and emotional development of offspring, as well as contribute to behavioral problems and interpersonal relationship difficulties later in life [7,8]. In addition, perinatal mood disorders can decrease the rate of breastfeeding [9], and disrupt the quality of mother-infant attachment [10]. Given the high risk and prevalence of perinatal depression and anxiety, it is necessary to engage in extensive theoretical discussions and empirical research on the association between perinatal depression and anxiety.

Numerous studies have shown that perinatal depression and anxiety symptoms are heterogeneous, with a high degree of diversity in their onset, course, duration and severity [11,12,13]. Both domestic and international studies have shown that the prevalence of depression and anxiety varies at different stages of the perinatal period [14,15], and there is no definitive pattern regarding which has a higher or lower prevalence of mood disorders during pregnancy and postpartum. Two foreign studies on depression trajectories in perinatal women both found five trajectories, including trajectory categories of no depressive symptoms, depression during pregnancy, and postpartum depression [16,17]. Two domestic studies on pregnant women both identified three depression trajectories, including high symptom group, moderate symptom group and low symptom group [18,19]. Empirical studies of anxiety trajectories during the perinatal period are relatively limited compared to perinatal depression. A longitudinal study of perinatal anxiety among African women identified four distinct anxiety trajectory categories: low anxiety, increasing anxiety before and after childbirth, overall increasing anxiety, and transient high anxiety in the postpartum period [20]. Another study of potential trajectories of perinatal anxiety symptoms from pregnancy to the early postpartum period determined three trajectory groups: very low–stable, low–stable, and moderate–stable [21]. While these studies all indicate the existence of different categories of depression and anxiety trajectories during the perinatal period, providing evidence for longitudinal trajectory studies on perinatal depression and anxiety, existing studies are inconsistent in the number of trajectories, symptom continuity or variability, and vary in results depending on the study population, location and the duration of follow-up.

In previous individual-centered research, it can be seen that the independent developmental trajectories of antenatal depression and anxiety are very similar in number and shape [20,22]. Depression and anxiety in most pregnant women can be maintained at relatively low levels over time, while a small number of individuals show stable high levels of depression and anxiety or an increase after childbirth [17,20,22]. Furthermore, variable-centered studies have confirmed that depression and anxiety symptoms are significantly correlated and co-morbid [23,24]. Regarding the interaction between depression and anxiety at different stages of the perinatal period, many studies have found that prenatal anxiety and depressive symptoms predicted postpartum anxiety and depression [25,26,27]. So, do these results imply that there are common trends between perinatal depression and anxiety? Traditional variable-centered studies ignored the heterogeneity of developmental patterns of perinatal depression and anxiety, and it is difficult to determine the exact pattern of the relationship between perinatal depression and anxiety by examining the characteristics of perinatal depression and anxiety only at the level of the variable, without distinguishing the heterogeneity in the developmental patterns of these two. The strength of the individual-centered approach lies in identifying heterogeneous developmental trajectories of different types of perinatal depression and anxiety. Previous research has separately examined the heterogeneous developmental trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety but has not simultaneously investigated the co-occurrence patterns of these two symptoms. Given the limitations of prior research, we employed an individual-centered approach (parallel process latent class growth modeling (PP-LCGM)) to explore the joint developmental trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety. This approach allows for the identification of distinct developmental clusters based on the intra-individual joint trajectories of the two symptoms [28]. This method has been successfully applied in studies of the joint trajectories of loneliness, depressive symptoms, and social anxiety from childhood to adolescence [29], anxiety–depressive trait and trait aggression in adolescents [30], and depressive and anxiety symptoms in college students [31], but has not yet been used to explore the joint developmental trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety. This study further explores the joint developmental trajectories of the two, thereby elucidating the probable reasons for the high correlation and comorbidity between perinatal depression and anxiety at the individual level.

The high correlation and co-morbidity between perinatal depression and anxiety implies that there may be common developmental trajectories and pathogenic factors for both, and the multiple trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety also suggest that there may be specific risk factors leading to distinct symptom patterns. If high risk groups for perinatal depression and anxiety can be identified, as well as potential risk and protective factors, early monitoring, psychological health education, and cognitive behavioral therapy can be conducted to reduce the risk of severe depression and adverse perinatal outcomes [32]. Previous studies have indicated that a history of mental illness, pregnancy loss, unintended pregnancy, pregnancy complications, smoking, domestic violence, abuse history, life stress, and lack of social or partner support are risk factors for perinatal depression and anxiety [33,34,35,36,37]. Pregnancy complications, history of mental illness, and perinatal anxiety are associated with the high depression trajectory [12,37,38,39]. Low income, higher levels of stress, history of depression and lack of partner support are associated with the high anxiety trajectory group [13,20]. Although there have been several studies on the predictors of perinatal depression and anxiety, the research on the longitudinal joint trajectory of perinatal depression and anxiety and its related factors is still lacking. Notably, although previous studies have emphasized social support as a protective factor for perinatal depression and anxiety, may independently influence the developmental trends of depression and anxiety [33,35,40,41], there are currently no studies examining the effects of social support on the joint developmental trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety.

Therefore, the present study aimed to examine the heterogeneous joint trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety and to assess relevant predictive factors. The protective effect of social support is highlighted, providing empirical evidence for targeted early intervention and treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This is a longitudinal study of perinatal depression and anxiety from the Affiliated Women’s Hospital of Jiangnan University. The study was carried out from January 2022 to December 2023, with a total of 1658 women selected from the outpatient department. Among them, 1062 women met the inclusion criteria of this study and were analyzed in this paper, while 596 women were lost to follow-up. The process of participant selection is presented in Figure S1. The attrition analysis showed that there were no statistically significant differences in age (t = −1.624, p = 0.104), education level (χ2 = 3.963, p = 0.138), and monthly income level (χ2 = 4.51, p = 0.105) between the participants who continued in the study and those who were lost to follow-up, indicating that the attrition of participants in this study was random. The survey questionnaires were completed anonymously and coded digitally. Participants were also informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time. This study obtained written consent and ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Women’s Hospital of Jiangnan University (2023-01-0628-15).

2.2. Procedure

Research data were collected using the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) and generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD-7) in the following four periods: early pregnancy (T1, 0–13+6 weeks); mid-pregnancy (T2, 14–27+6 weeks); late pregnancy (T3, 28–41 weeks); and postpartum 42 days (T4). Participants also completed the general information questionnaire and perceived social support scale (PSSS) at T1. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) aged 18–40; (2) early pregnancy (before 13+6 weeks); and (3) voluntary informed consent. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) family history of mental illness; (2) severe heart disease, infectious disease, severe preeclampsia; and (3) withdrawal of informed consent, lack of cooperation, or incomplete questionnaires.

2.3. Research Tools

2.3.1. General Information Questionnaire

The general information questionnaire included the following demographic data: age; monthly income level (<5000 CNY, 5000–10,000 CNY, >10,000 CNY); education level (college and below, undergraduate, master and above); planned pregnancy (yes, no); regular exercise (walking >5000 steps/day, no); paid work (yes, no); work stress (yes, no); adverse maternal history (yes, no); number of births (0, ≥1); gestational diabetes (yes, no); gestational hypertension (yes, no); history of anxiety (yes, no); history of depression (yes, no); preterm birth (yes, no); newborn sex (male, female); and delivery mode (cesarean section, vaginal delivery).

2.3.2. Patient Health Questionnaire

The patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) developed by Kroenke et al. [42] was used to assess the level of perinatal depression with a total of 9 items. The scale utilizes a four-point rating (0 = not at all, 3 = nearly every day). Scores range from 0 to 27. A higher PHQ-9 score indicates a higher severity of depression, with cutoff points of 5 and 10 signifying mild and moderate depression symptoms, respectively [42]. This measure showed relatively high internal consistency at each time point (Cronbach’s α: αT1 = 0.830, αT2 = 0.835, αT3 = 0.837, αT4 = 0.847).

2.3.3. Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale

The generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD-7), developed by Spitzer et al. [43], was used to assess the level of perinatal anxiety. The scale consists of 7 items rated on a four-point scale (0 = not at all, 3 = nearly every day), with scores ranging from 0 to 21. Higher GAD-7 scores indicate more severe anxiety levels, with a cutoff point of 7 indicating the presence of anxiety symptoms [44]. This measure showed good internal consistency at each time point (Cronbach’s α: αT1 = 0.833, αT2 = 0.818, αT3 = 0.824, αT4 = 0.811).

2.3.4. Perceived Social Support Scale

The perceived social support scale (PSSS) developed by Zimet et al. [45], translated and revised by Qianjin Jiang [46] was used to measure the perceived social support of the perinatal women. It consists of 12 items in 3 subscales, rated on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree), with scores ranging from 12 to 84. The scale includes three dimensions: family support, friend support, and other support, with higher total scores indicating greater social support for the individual. The Cronbach’s coefficient α of the total scale in this study was 0.887, and the internal consistency (Cronbach’s αs) of family support, friend support, and other support in the subscales were 0.745, 0.712, and 0.747, respectively, which have reached the psychometric standard.

2.4. Data Analysis

Firstly, descriptive statistics were conducted on the research variables to explore the correlation between the levels of depression and anxiety at various measurement time points and their correlation with social support variables.

Secondly, the latent growth model and latent class growth model were constructed to examine the developmental trajectories and classes of perinatal depression and anxiety [47,48]. The latent growth model was used to investigate the trajectory of perinatal depression and anxiety changes, and whether there were significant individual differences in the initial level and development rate. The model was considered well-fitted when the confirmatory fit index (CFI) and the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) were ≥0.95, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was <0.08 [49].

Subsequently, the latent class growth model (LCGM) was separately constructed for perinatal depression and anxiety to explore their potential categories. The following parameters were used to determine the optimal number of categories and the fit of the model: Akaike information criterion (AIC) [50]; Bayesian information criterion (BIC) [51]; a-BIC (smaller values indicate a better fit of the model with increasing class numbers) [52]; Entropy (entropy value above 0.70 suggests high classification accuracy) [53]; BLRT (boot-strapped likelihood ratio test); and VLMR (Vuong-lo-mendell-rubin likelihood ratio test). The acceptance of K group classification and rejection of k-1 group classification was based on results from BLRT and VLMR test reaching significance (p < 0.05) [54,55]; the proportion of each subgroup group was not less than 3% [56]. In addition to these fit indices, the practical interpretability of the trajectory classes should also be considered [55].

Furthermore, the parallel-process latent class growth model (PPLCGM) [48] was established to investigate the joint developmental trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety. This model extends the typical univariate latent class growth model to parallel processes, considering multiple growth trajectories simultaneously [57].

Finally, multinomial logistic regression was developed to explore whether demographic variables and social support significantly predicted the joint developmental trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety. Prior to the multinomial logistic regression analysis, we assessed the model for multicollinearity. The tolerance values for each independent variable were all well above 0.1, and the variance inflation factors (VIFs) were all below 10, indicating the absence of multicollinearity. This study used SPSS 23.0 for descriptive, correlation, and regression analysis, Mplus 8.3 for latent class growth model analysis, and full information maximum likelihood (FIML) analyses to handle missing values, minimizing biases in regression coefficient and standard error estimates [58].

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis and Correlation Analysis

A total of 1062 pregnant women completed 4 screenings for anxiety and depression from early pregnancy to 42 days postpartum. Descriptive statistics of participants’ demographic characteristics were shown in Table 1. Four measurements of perinatal depression and anxiety were significantly positively correlated and significantly negatively correlated with all variables of social support (Table S1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants (n = 1062).

3.2. Latent Class Growth Analysis for Perinatal Depression and Anxiety

First, from the fit indices of the three models (Table S2), it was found that compared with the linear and quadratic model, the free estimated latent growth model of perinatal depression and anxiety fitted relatively well. In addition to the non-significant rate of change for perinatal depression (σ2dep = 0.065, p = 0.092), the variances in the initial levels of perinatal depression and anxiety (σ2dep = 12.671, p < 0.001, σ2anx = 8.545, p < 0.001) and in the slope of perinatal anxiety (σ2anx = −0.607, p < 0.01) were statistically significant, indicating that there may be multiple subgroups with different trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety symptoms, respectively, which laid the foundation for the latent class growth model analysis.

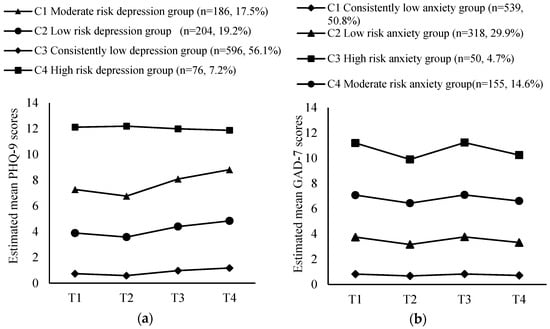

Next, the latent class growth model (LCGM) was used to identify the optimal number of five latent classes for the developmental trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety, respectively (Table 2). For depression, a subgroup included in the five-class model accounted for only two and a half percent of the sample, leading to the exclusion of the five-class model. The AIC, BIC, and a-BIC values decreased gradually with an increase in trajectory numbers, and the decrease slowed down when it dropped to class four. For anxiety, similar patterns were observed with AIC, BIC, and a-BIC values showing a gradual decrease with an increase in trajectory numbers, and then the decrease was not significant when it dropped to class four. The results of the VLMR test indicated no significance in the five-class model, leading to its exclusion. Based on the model’s fit indices, both three-class and four-class models of perinatal depression and anxiety trajectories are acceptable. Consequently, trajectory plots were generated for both three-class and four-class models, respectively (Figure 1 and Figure S2). The four-class model of perinatal depression and anxiety trajectories, in comparison, allows for the identification of more refined subgroups, aligning with the detailed scoring criteria of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7. In summary, four-class model was chosen for the developmental trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety.

Table 2.

Model fit indices for latent class growth models of perinatal depression and anxiety.

Figure 1.

(a) Developmental trajectory of perinatal depression; (b) Developmental trajectory of perinatal anxiety.

Specifically, the trajectories of perinatal depression were classified into the following four classes: class 1 (n = 186) showed an overall moderate level, with an increasing trend in late pregnancy and postpartum, classified as the “moderate risk depression group”; class 2 (n = 204) presented an overall low level, with a slight increase in the postpartum period, classified as the “low risk depression group”; class 3 (n = 596) consistently maintained at a very low level, as the “consistently low depression group”; and class 4 (n = 76) showed an overall high-risk level, as the “high risk depression group” (Figure 1a). Similarly, the trajectories of perinatal anxiety were divided into the following 4 classes: class 1 (n = 539) consistently remained at a very low level, defined as the “consistently low anxiety group”; class 2 (n = 318) displayed a stable low level, as the “low risk anxiety group”; class 3 (n = 50) presented an overall high-risk level, with a peak in the late-pregnancy period, identified as the “high risk anxiety group”; and class 4 (n = 155) maintained a stable moderate level, hovering around the cut-off value of 7 points, classified as the “moderate risk anxiety group” (Figure 1b). The parameters of the interception and slope were shown in Table S3.

3.3. Parallel-Process Latent Class Growth Analysis of Perinatal Depression and Anxiety

The parallel process latent growth analysis (Table S4) indicated that the free estimated latent growth model had a better fit compared to linear and quadratic growth models (χ2(df) = 190.604(18), p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.095, CFI = 0.983, TLI = 0.974, SRMR = 0.020). In addition to the non-significant rate of change for perinatal depression (σ2dep = 0.054, p = 0.146), the variances in the initial levels of perinatal depression and anxiety (σ2dep = 12.609, p < 0.001, σ2anx = 8.574, p < 0.001) and in the slope of anxiety (σ2anx = −0.586, p = 0.02) were statistically significant, indicating the presence of multiple groups with different trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety symptoms, and that latent class analysis using parallel processes for both was necessary.

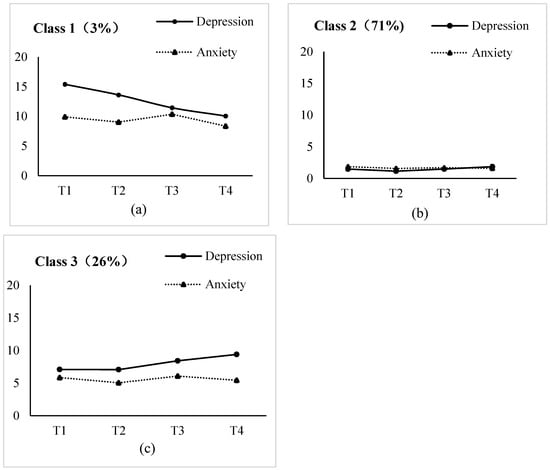

Then, the parallel process latent class growth model was developed for perinatal depression and anxiety, extracting from one to five latent classes to identify the optimal number of the joint developmental trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety (Table 3). As the number of trajectories increased, the values of AIC, BIC, and a-BIC decreased gradually, and the decrease slowed down when reaching class three. The values of VLMR and BLRT suggested that the models of class two and three were acceptable. Based on the fit indices, both two- and three-class models are acceptable. Consequently, we generated trajectory plots for two- and three-class models, respectively (Figure 2 and Figure S3). In comparison, the two-class model overlooks a high-risk group. Taking all into account, the three-class model was determined as the best-fitting model for joint developmental trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety.

Table 3.

Fit indices of parallel process latent class growth model for perinatal depression and anxiety.

Figure 2.

Joint developmental trajectory classes of perinatal depression and anxiety: (a) Class 1—high–slightly decreasing depression and high decreasing anxiety group; (b) Class 2—low–stable depression and low–stable anxiety group; (c) Class 3—moderate–slightly increasing depression and moderate–decreasing anxiety group.

Based on this model, the joint developmental trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety were classified into the following 3 classes (Figure 2): class 1 was the smallest, approximately 3% (n = 33), with high levels of perinatal depression and anxiety, and a significant decrease in perinatal anxiety, which was named “high–slightly decreasing depression and high decreasing anxiety group” (Intercept: Idep = 14.415, p < 0.001, Ianx = 9.961, p < 0.001, Slope: Sdep = −0.291, p = 0.402, Sanx = −1.339, p < 0.001); class 2 consisted of 71% of pregnant women (n = 754) with consistently low levels of perinatal depression and anxiety, named “low–stable depression and low–stable anxiety group” (Idep = 1.293, p < 0.001, Ianx = 1.744, p < 0.001, Sdep = 0.029, p = 0.344, Sanx = −0.135, p = 0.03); class 3 included 26% of pregnant women (n = 275) with moderate initial levels of depression and anxiety, and a decreasing trend in anxiety and a slightly increasing trend in depression, named “moderate–slightly increasing depression and moderate–decreasing anxiety group” (Idep = 6.925, p < 0.001, Ianx = 5.804, p < 0.001, Sdep = 0.144, p = 0.375, Sanx = −0.769, p < 0.001). The levels of perinatal depression and anxiety for the three groups at 4 measurement points were shown in Table S5.

3.4. Predictors of Joint Developmental Trajectories of Perinatal Depression and Anxiety

Using demographic variables, perinatal-related information and social support at baseline as independent variables, the classes of the joint trajectory of perinatal depression and anxiety as dependent variables, and the low–stable depression and low–stable anxiety group as the reference group, multinomial logistic regression analysis were used to examine the predictors of joint developmental trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety (Table 4). The results found that pregnant women with adverse maternal history, history of anxiety and depression were 4.875 times (95% CI: 1.260–18.857), 10.069 times (95% CI: 1.289–78.679), and 9.515 times (95% CI: 1.437–63.007) more likely to belong to the high–slightly decreasing depression and high decreasing anxiety group, respectively. Pregnant women with job stress, history of previous anxiety and depression were 5.251, 12.165 and 4.127 times more likely to belong to the moderate–slightly increasing depression and moderate–decreasing anxiety group, respectively. However, pregnant women with regular exercise (OR: 0.533) and paid work (OR: 0.369) were less likely to belong to the moderate–slightly increasing depression and moderate–decreasing anxiety group. Additionally, higher levels of social support reduced the odds of being allocated in the high–slightly decreasing depression and high decreasing anxiety group and the moderate–slightly increasing depression and moderate–decreasing anxiety group (ORs: 0.556–0.754).

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis of demographic and psychosocial factors on the subgroups of the joint developmental trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety.

4. Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of Independent Developmental Trajectories of Perinatal Depression and Anxiety

This study identified four perinatal depression trajectory groups and four perinatal anxiety trajectory groups. The four depression trajectory groups were: moderate-risk group, low-risk group, consistently low group and high-risk group. Around 75% of pregnant women belonged to the low-risk group and consistently low group, with depression scores below the clinically significant threshold. This finding was generally consistent with those of prior studies employing diverse measurement and statistical methodologies across varying environmental contexts [12,18,22,59,60]. The high risk group was characterized by a persistent high risk level of depression, indicating that for the majority of women suffering from postpartum depression, depressive symptoms may have appeared even before pregnancy, during pregnancy, adolescence, or in adulthood, representing a continuation and variation in early mental health problems [61,62]. In our study, the high risk group for depression showed a significantly increasing trend of depression scores in the postpartum period, while a study conducted in Norway [63] found a decreasing trend only in postpartum depression trajectories. This may be related to the development of the country, higher level of education and the relative superiority of social resources, which could potentially reduce the risk of depressive symptoms. A longitudinal study conducted in China identified groups with prenatal and postpartum depression [19], with proportions aligning with the high-risk group in this study. This suggests that the risk of perinatal depression may manifest at different stages, both prenatally and postnatally. Similarly, the four perinatal anxiety trajectory groups also showed consistently low group, low-risk group, high-risk group, and moderate-risk group, which is both similar and specific to previous studies. Our findings revealed that over 80% of women experienced either very low or low levels of anxiety symptoms throughout the entire period, which aligns with the research on anxiety trajectories of 1445 perinatal women in Canada [64] and 778 women in West Africa [20]. Less than 1/5 of pregnant women exhibited mild to moderate anxiety symptoms, and the trends of the 4 trajectories were similar from early pregnancy to 42 days postpartum, with a declining trend in anxiety levels at 42 days postpartum. In contrast, Barthel et al. [20] found less than one-fifth of pregnant women displayed three different moderate to high anxiety trajectory groups. However, both studies revealed a subgroup of women whose anxiety scores increased around delivery and subsequently decreased, indicating the prevalence of delivery-related anxiety and the necessity for timely psychological interventions before and after delivery. Meanwhile, perinatal anxiety and depressive symptoms show a degree of similarity in trends, supporting the idea that depression and anxiety are independent and interdependent.

4.2. Characteristics of Joint Developmental Trajectories of Perinatal Depression and Anxiety

The present study identified three joint developmental trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety, among the three groups, the “high–slightly decreasing depression and high decreasing anxiety group” had the smallest proportion of pregnant women, with both depression and anxiety levels remaining high, and the “low–stable depression and low–stable anxiety group” had the highest proportion of pregnant women, with consistently low levels of depression and anxiety, while the “moderate–slightly increasing depression and moderate–decreasing anxiety group” had a moderate proportion of pregnant women, with moderate initial levels of depression and anxiety, followed by a declining trend in anxiety. This finding indicated that the majority of pregnant women belonged to the low–stable depression and low–stable anxiety group, suggesting that for most pregnant women, depressive and anxiety symptoms were generally low and stable, consistent with other research [12,59,60,64,65]. Only a minority of pregnant women belonged to the high–slightly decreasing depression and high decreasing anxiety group, indicating that the prevalence of co-morbid high-risk depression and anxiety among pregnant women is not high, which may also be related to our selection of individuals with fewer emotional symptoms as the study participants. The results of the joint developmental trajectories revealed a certain degree of similarity and commonality in the initial levels and trends of anxiety and depression symptoms among the three groups, supporting their comorbidity [66]. This implied that regular perinatal screening should not only focus on depressive mood but also be attentive to all emotional disorders, including anxiety. Additionally, it was interesting to note that the trajectories of perinatal anxiety symptoms exhibited varying degrees of decreasing trends in all three groups, especially more pronounced in the postpartum period, further confirming the findings of Buist et al. [67]. Whereas the trajectory of perinatal depression still had the risk of increasing, indicating that pregnant women need to possess emotional regulation strategies and problem-solving skills to effectively cope with their distress and prevent postpartum negative emotions [68].

4.3. Predictors of Joint Developmental Trajectories of Perinatal Depression and Anxiety

This study identified risk and protective factors associated with the joint developmental trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety. Pregnant women with a history of adverse pregnancy outcomes, anxiety, and depression were more likely to belong to the high–slightly decreasing depression and high decreasing anxiety group, and those with high work stress, history of anxiety and depression were more likely to belong to the moderate–slightly increasing depression and moderate–decreasing anxiety group. It can be seen that adverse maternal history is an important factor influencing perinatal depression and anxiety [36]. Women who have experienced adverse pregnancy outcomes often worry early in pregnancy, fearing the recurrence of miscarriage, fetal deformities, and preterm birth. Persistent anxiety may diminish or disappear after the successful delivery. The history of previous anxiety and depression is major risk factor, and several studies have confirmed that women who have experienced anxiety and depression in the past are more likely to be depressed and anxious during pregnancy and postpartum [12,33,34,69,70]. Indeed, for individuals with a history of anxiety and depression, pregnancy and childbirth as stressful events can intensify stress responses, leading to increased emotional instability and vulnerability. Work stress, as one of the factors affecting maternal mental health, has been mentioned in previous findings [12,64]. The dual stress of work and childbirth not only triggers hormonal changes, such as, activation of the HPA axis, the release of corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH), and cortisol levels, but may also exacerbate the physical discomforts associated with pregnancy and increase susceptibility and vulnerability to perinatal depression or anxiety [71].

Furthermore, pregnant women who engage in regular exercise and paid work are not categorized into the moderate–slightly increasing depression and moderate–decreasing anxiety group, indicating that exercise and paid work seem to be protective factors. This finding, though interesting, is not difficult to understand, studies have shown that physical exercise during pregnancy can reduce the incidence and severity of perinatal depression [72,73]. It can be seen that appropriate exercise can enhance physical fitness and is a beneficial remedy for the smooth delivery and emotional regulation of pregnant women. Similarly, a previous study has confirmed that the mental health and quality of life scores of mothers with paid work were significantly higher than those of mothers who did not work [74]. Therefore, paid work with the appropriate intensity can provide some economic security and social support, reflect personal value, and reduce inexplicable anxiety in pregnant women.

Additionally, it has been found that social support significantly increases the likelihood of individuals belonging to the low–stable depression and low–stable anxiety group, indicating that social support as a protective factor, can significantly reduce the risk of perinatal depression and anxiety [20,75]. According to the stress-buffering model of social support, social support acts as a buffer between perceived stress and mental health, it can mitigate the impact of stress on mental health by alleviating individual stress appraisal responses [76]. Given that pregnancy and childbirth are stressful events, adequate social support is particularly important for pregnant women to resist stress and accumulate positive emotions. Hormonal fluctuations during pregnancy, including variations in oxytocin, cortisol, and serotonin, are closely associated with mood regulation. The release of oxytocin enhances maternal-infant bonding and alleviates stress [10]. Elevated cortisol levels during pregnancy may influence maternal mood [77], while social support buffers stress responses, mitigating excessive cortisol secretion [78]. The increase in oxytocin around childbirth and the sharp decline in estrogen explain the observed decrease in anxiety symptoms and the persistent risk of depression in this study, highlighting the importance of sustained social support in preventing depression. Therefore, at the family level, mental health education programs for partners and family members can be implemented, along with providing effective companionship to enhance their ability to recognize emotional changes in pregnant women, thereby helping to alleviate emotional distress and prevent depressive symptoms [79]. At the community and peer level, mutual support groups or online support communities for pregnant women can be established to promote peer interaction and mutual support [79], and regular mental health promotion activities can be organized to disseminate knowledge of perinatal mood management. From a healthcare policy perspective, promoting the inclusion of perinatal mental health screening in routine prenatal check-ups ensures that high-risk pregnant women receive timely interventions such as mindfulness training and cognitive behavioral therapy [80].

4.4. Strengths, Limitations, and Further Research

The current study displays several major strengths and conducted repeated assessments of anxiety and depression during early pregnancy, mid-pregnancy, late pregnancy, and postpartum from a dynamic longitudinal perspective. It analyzes the independent and joint developmental trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety, providing important insights and reference value for clinical diagnosis and treatment. Additionally, the study explores the risk and protective factors of the joint developmental trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety, offering clinical guidance for screening and prevention of perinatal mental health.

The study has several limitations. Firstly, the current sample size may not be sufficient for fine identification of joint trajectories of depression and anxiety. Previous studies with larger sample sizes have been able to differentiate five or more heterogeneous trajectories of anxiety and depression [64]. The relatively small size of the high symptom trajectory group may affect the precision of the correlation between predictors and each group. Future research could benefit from expanding the sample size to more precisely identify joint developmental trajectories and predictors. Secondly, this study only investigated the 4 following periods: early pregnancy; mid-pregnancy; late pregnancy; and 42 days postpartum. Future research could extend the investigation period to one year postpartum to comprehensively characterize the entire developmental trend of perinatal depression and anxiety. Thirdly, this study is limited by its inability to encompass all potential influencing factors, and the use of self-report questionnaires to assess psychosocial variables may introduce response bias. Future research could consider network analysis to accurately explore the association patterns between potential influencing factors and perinatal anxiety and depressive symptoms. Lastly, the study does not investigate which pregnant women received standard treatments for depression and anxiety, which could potentially alter their trajectories of perinatal mood disorders. Future research could explore whether standardized psychological interventions and necessary drug treatments could change the trajectories of perinatal anxiety and depression.

5. Conclusions

We found three joint developmental trajectories of perinatal anxiety and depression. Adverse maternal history, history of anxiety and depression, and work stress were risk factors, while regular exercise, paid work and social support served as protective factors. Perinatal healthcare providers should pay attention to the mental health history of pregnant women, conduct multiple assessments of perinatal anxiety and depression, prioritize individuals with risk factors, encourage pregnant women to engage in regular exercise, participate in work, and provide them with greater social support. This study offers practical guidance for early screening, dynamic monitoring, and personalized interventions for perinatal depression and anxiety.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare13111251/s1, Table S1: Means, standard deviations and correlation analysis of variables; Table S2: Fit indices of latent variable growth models for perinatal depression and anxiety; Table S3: Parameter information of latent class growth models for perinatal depression and anxiety; Table S4: Fit indices of parallel process latent growth models for perinatal depression and anxiety; Table S5: Mean and standard deviation of perinatal depression and anxiety in different developmental classes; Figure S1: The flow chart of participant selection and follow-up; Figure S2: (a) Developmental trajectory of perinatal depression in the three-class model; (b) Developmental trajectory of perinatal anxiety in the three-class model; Figure S3: Joint developmental trajectories of perinatal depression and anxiety in the two-class model: (a) Class 1—low–stable depression and anxiety group; and (b) Class 2—high-increasing depression and high–slightly decreasing anxiety group.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J. and X.Z.; methodology, M.J.; software, M.J.; validation, H.Z., Z.W. and Z.B.; formal analysis, Z.B.; investigation, M.J.; resources, M.J.; data curation, H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J.; writing—review and editing, X.Z.; visualization, Y.F.; supervision, Y.F.; project administration, X.Z.; funding acquisition, M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Wuxi Science and Technology Bureau’s “Taihu Light” Technology Research Project, grant number K20221034; Innovation and Entrepreneurship Program of Jiangsu Province, grant number JSSCRC2021569; Wuxi “Taihu Talent Plan” High-End Medical and Health Talents Project, grant number (2020)50 Document of Xiwei Party and General Project of Philosophy And Social Science Research of Colleges in Jiangsu, grant number 2023SJYB0897.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study obtained written consent and ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Women’s Hospital of Jiangnan University (protocol code 2023-01-0628-15, date 6 July 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to all the women who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nisar, A.; Yin, J.; Waqas, A.; Bai, X.; Wang, D.; Rahman, A.; Li, X. Prevalence of perinatal depression and its determinants in Mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 1022–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A.R.; Gordon, H.; Lindquist, A.; Walker, S.P.; Homer, C.S.; Middleton, A.; Cluver, C.A.; Tong, S.; Hastie, R. Prevalence of perinatal depression in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2023, 80, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Shao, C.; Tang, C. Risk Factors of Perinatal Negative Mood and Its Influence on Prognosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2024, 17, 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.S.; Saade, G.R.; Simhan, H.N.; Monk, C.; Haas, D.M.; Silver, R.M.; Mercer, B.M.; Parry, S.; Wing, D.A.; Reddy, U.M. Trajectories of antenatal depression and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, 108.e1–108.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, R.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, W. Antenatal depressive symptoms and the risk of preeclampsia or operative deliveries: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schetter, C.D.; Tanner, L. Anxiety, depression and stress in pregnancy: Implications for mothers, children, research, and practice. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2012, 25, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J.H. Perinatal depression and infant mental health. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2019, 33, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, A.; Pearson, R.M.; Goodman, S.H.; Rapa, E.; Rahman, A.; McCallum, M.; Howard, L.M.; Pariante, C.M. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet 2014, 384, 1800–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coo, S.; García, M.I.; Mira, A.; Valdés, V. The role of perinatal anxiety and depression in breastfeeding practices. Breastfeed. Med. 2020, 15, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanekasu, H.; Shiraiwa, Y.; Taira, S.; Watanabe, H. Primiparas’ prenatal depressive symptoms, anxiety, and salivary oxytocin level predict early postnatal maternal–infant bonding: A Japanese longitudinal study. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2024, 27, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A.; Beard, J.R.; Galea, S. Epidemiologic heterogeneity of common mood and anxiety disorders over the lifecourse in the general population: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2009, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Waerden, J.; Galéra, C.; Saurel-Cubizolles, M.-J.; Sutter-Dallay, A.-L.; Melchior, M.; Group, E.M.C.C.S. Predictors of persistent maternal depression trajectories in early childhood: Results from the EDEN mother–child cohort study in France. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 1999–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Bowen, A.; Feng, C.X.; Muhajarine, N. Trajectories of maternal depressive and anxiety symptoms from pregnancy to five years postpartum and their prenatal predictors. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Xu, D.; Cai, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, H.; Gong, W. Detection rate of depression symptoms at different time points in perinatal women and influencing factors. Chin. J. Ment. Health 2021, 35, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbrother, N.; Janssen, P.; Antony, M.M.; Tucker, E.; Young, A.H. Perinatal anxiety disorder prevalence and incidence. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 200, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, P.A.; Bennett, I.M.; Elo, I.T.; Mathew, L.; Coyne, J.C.; Culhane, J.F. Distinct trajectories of perinatal depressive symptomatology: Evidence from growth mixture modeling. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 169, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellowski, J.A.; Bengtson, A.M.; Barnett, W.; DiClemente, K.; Koen, N.; Zar, H.J.; Stein, D.J. Perinatal depression among mothers in a South African birth cohort study: Trajectories from pregnancy to 18 months postpartum. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 259, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y.; He, C.; Wang, J.; Tang, J.; Hou, H.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W. Factors associated with the mental health status of pregnant women in China: A latent class analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 1017410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Li, H.; Xu, D.R.; Wu, Y.; Liu, H.; Gong, W. Trajectories of perinatal depressive symptoms from early pregnancy to six weeks postpartum and their risk factors—A longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 275, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthel, D.; Kriston, L.; Barkmann, C.; Appiah-Poku, J.; Te Bonle, M.; Doris, K.Y.E.; Esther, B.K.C.; Armel, K.E.J.; Mohammed, Y.; Osei, Y. Longitudinal course of ante-and postpartum generalized anxiety symptoms and associated factors in West-African women from Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 197, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Feng, C.; Bowen, A.; Muhajarine, N. Latent trajectory groups of perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms from pregnancy to early postpartum and their antenatal risk factors. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2018, 21, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredriksen, E.; von Soest, T.; Smith, L.; Moe, V. Patterns of Pregnancy and Postpartum Depressive Symptoms: Latent Class Trajectories and Predictors. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2017, 126, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Droncheff, B.; Warren, S.L. Predictive utility of symptom measures in classifying anxiety and depression: A machine-learning approach. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 312, 114534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Mesa, E.; Kabukcuoglu, K.; Blasco, M.; Körükcü, O.; Ibrahim, N.; González-Cazorla, A.; Cazorla, O. Comorbid anxiety and depression (CAD) at early stages of the pregnancy. A multicultural cross-sectional study. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 270, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, K.-A.; McMahon, C.; Austin, M.-P. Maternal anxiety during the transition to parenthood: A prospective study. J. Affect. Disord. 2008, 108, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, H.F.; Murray, L.; Royal-Lawson, M.; Cooper, P.J. Antenatal anxiety disorder as a predictor of postnatal depression: A longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 129, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roomruangwong, C.; Kanchanatawan, B.; Sirivichayakul, S.; Maes, M. Antenatal depression and hematocrit levels as predictors of postpartum depression and anxiety symptoms. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 238, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagin, D.S.; Tremblay, R.E. Developmental trajectory groups: Fact or a useful statistical fiction? Criminology 2005, 43, 873–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Huebner, E.S.; Tian, L. Joint trajectories of loneliness, depressive symptoms, and social anxiety from middle childhood to early adolescence: Associations with suicidal ideation. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 32, 1733–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugre, J.R.; Dumais, A.; Dellazizzo, L.; Potvin, S. Developmental joint trajectories of anxiety-depressive trait and trait-aggression: Implications for co-occurrence of internalizing and externalizing problems. Psychol. Med. 2020, 50, 1338–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Huang, L.; Qu, D.; Bu, H.; Chi, X. Self-compassion predicted joint trajectories of depression and anxiety symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic: A five-wave longitudinal study on Chinese college students. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 319, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Guo, X.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y. Effects of perinatal cognitive behavioral therapy on delivery mode, fetal outcome, and postpartum depression and anxiety in women. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 2022, 8304405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biaggi, A.; Conroy, S.; Pawlby, S.; Pariante, C.M. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 191, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Abri, K.; Edge, D.; Armitage, C.J. Prevalence and correlates of perinatal depression. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2023, 58, 1581–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, L.E.; Lara-Cantú, M.A.; Navarro, C.; Gómez, M.E.; Morales, F. Psychosocial factors predicting postnatal anxiety symptoms and their relation to symptoms of postpartum depression. Rev. Investig. Clínica 2012, 64, 625–633. [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore, E.R.; Côté-Arsenault, D.; Tang, W.; Glover, V.; Evans, J.; Golding, J.; O’Connor, T.G. Previous prenatal loss as a predictor of perinatal depression and anxiety. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 198, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Wu, J.; Chen, X. Risk factors of perinatal depression in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmc Psychiatry 2022, 22, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoma, I.; Korhonen, M.; Salmelin, R.K.; Helminen, M.; Tamminen, T. Long-term trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms and their antenatal predictors. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 170, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekel, S.; Ein-Dor, T.; Ruohomäki, A.; Lampi, J.; Voutilainen, S.; Tuomainen, T.-P.; Heinonen, S.; Kumpulainen, K.; Pekkanen, J.; Keski-Nisula, L. The dynamic course of peripartum depression across pregnancy and childbirth. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2019, 113, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedaso, A.; Adams, J.; Peng, W.; Sibbritt, D. The association between social support and antenatal depressive and anxiety symptoms among Australian women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Le, T.; Lu, Y.; Shi, X.; Xiang, L.; Liu, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, M.; Wang, J.; Xu, D. Distinct trajectories of perinatal depression in Chinese women: Application of latent growth mixture modelling. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, X.; An, D.; McGonigal, A.; Park, S.-P.; Zhou, D. Validation of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) among Chinese people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2016, 120, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimet, G.D.; Powell, S.S.; Farley, G.K.; Werkman, S.; Berkoff, K.A. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Personal. Assess. 1990, 55, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q. Understanding the Social Support Scale. Chin. J. Behav. Med. Sci. 2001, 10, 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, T.E.; Duncan, S.C. The ABC’s of LGM: An introductory guide to latent variable growth curve modeling. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2009, 3, 979–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, K.S.; Parra, G.R.; Williams, N.A. An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 2): Longitudinal latent class growth analysis and growth mixture models. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2014, 39, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.t.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. Information measures and model selection. Int. Stat. Inst. 1983, 44, 277–291. [Google Scholar]

- Raftery, A.E. Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociol. Methodol. 1995, 25, 111–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sclove, S.L. Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika 1987, 52, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celeux, G.; Soromenho, G. An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. J. Classif. 1996, 13, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Bodner, T.E. Growth mixture modeling—Identifying and predicting unobserved subpopulations with longitudinal data. Organ. Res. Methods 2007, 10, 635–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund, K.L.; Asparoutiov, T.; Muthen, B.O. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2007, 14, 535–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubke, G.; Muthén, B.O. Performance of Factor Mixture Models as a Function of Model Size, Covariate Effects, and Class-Specific Parameters. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2007, 14, 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, R.A.; King, K.M.; Cauce, A.M.; Conger, R.D.; Robins, R.W. Cultural Orientation Trajectories and Substance Use: Findings From a Longitudinal Study of Mexican-Origin Youth. Child Dev. 2017, 88, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlomer, G.L.; Bauman, S.; Card, N.A. Best practices for missing data management in counseling psychology. J. Couns. Psychol. 2010, 57, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denckla, C.; Mancini, A.; Consedine, N.; Milanovic, S.; Basu, A.; Seedat, S.; Spies, G.; Henderson, D.; Bonanno, G.; Koenen, K. Distinguishing postpartum and antepartum depressive trajectories in a large population-based cohort: The impact of exposure to adversity and offspring gender. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 1139–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikman, A.; Axfors, C.; Iliadis, S.I.; Cox, J.; Fransson, E.; Skalkidou, A. Characteristics of women with different perinatal depression trajectories. J. Neurosci. Res. 2020, 98, 1268–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisner, K.L.; Sit, D.K.; McShea, M.C.; Rizzo, D.M.; Zoretich, R.A.; Hughes, C.L.; Eng, H.F.; Luther, J.F.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Costantino, M.L. Onset timing, thoughts of self-harm, and diagnoses in postpartum women with screen-positive depression findings. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, G.C.; Romaniuk, H.; Spry, E.; Coffey, C.; Olsson, C.; Doyle, L.W.; Oats, J.; Hearps, S.; Carlin, J.B.; Brown, S. Prediction of perinatal depression from adolescence and before conception (VIHCS): 20-year prospective cohort study. Lancet 2015, 386, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozd, F.; Haga, S.M.; Valla, L.; Slinning, K. Latent trajectory classes of postpartum depressive symptoms: A regional population-based longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 241, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrampour, H.; Tomfohr, L.; Tough, S. Trajectories of perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms in a community cohort. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2016, 77, 21112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, D.; Kehler, H.; Austin, M.-P.; Mughal, M.K.; Wajid, A.; Vermeyden, L.; Benzies, K.; Brown, S.; Stuart, S.; Giallo, R. Trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms during pregnancy and the first 12 months postpartum and child externalizing and internalizing behavior at three years. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falah-Hassani, K.; Shiri, R.; Dennis, C.-L. The prevalence of antenatal and postnatal co-morbid anxiety and depression: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 2041–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buist, A.; Gotman, N.; Yonkers, K.A. Generalized anxiety disorder: Course and risk factors in pregnancy. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 131, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani-Marghmaleki, F.; Mohebbi-Dehnavi, Z.; Beigi, M. Investigating the relationship between cognitive emotion regulation and the health of pregnant women. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2019, 8, 175. [Google Scholar]

- van der Zee-van, A.I.; Boere-Boonekamp, M.M.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, C.G.; Reijneveld, S.A. Postpartum depression and anxiety: A community-based study on risk factors before, during and after pregnancy. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 286, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giardinelli, L.; Innocenti, A.; Benni, L.; Stefanini, M.; Lino, G.; Lunardi, C.; Svelto, V.; Afshar, S.; Bovani, R.; Castellini, G. Depression and anxiety in perinatal period: Prevalence and risk factors in an Italian sample. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2012, 15, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickens, M.J.; Pawluski, J.L. The HPA axis during the perinatal period: Implications for perinatal depression. Endocrinology 2018, 159, 3737–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Terrones, M.; Barakat, R.; Santacruz, B.; Fernandez-Buhigas, I.; Mottola, M.F. Physical exercise programme during pregnancy decreases perinatal depression risk: A randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Soh, K.L.; Huang, F.; Khaza’ai, H.; Geok, S.K.; Vorasiha, P.; Chen, A.; Ma, J. The impact of physical activity intervention on perinatal depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 321, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke-Taylor, H.; Howie, L.; Law, M. Barriers to maternal workforce participation and relationship between paid work and health. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2011, 55, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, T.L.; Moulson, M.C.; Vigod, S.N.; Schoueri-Mychasiw, N.; Singla, D.R. The Role of Social Support in Perinatal Mental Health and Psychosocial Stimulation. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2024, 97, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, R.J.; Schuldberg, D. Social-support moderated stress: A nonlinear dynamical model and the stress buffering hypothesis. Nonlinear Dyn. Psychol. Life Sci. 2011, 15, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, L.M.; Myers, M.M.; Monk, C. Pregnant women’s cortisol is elevated with anxiety and depression—But only when comorbid. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2008, 11, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofman, Y.B.; Eng, Z.E.; Busse, D.; Godkin, S.; Campos, B.; Sandman, C.A.; Wing, D.; Yim, I.S. Cortisol reactivity and depressive symptoms in pregnancy: The moderating role of perceived social support and neuroticism. Biol. Psychol. 2019, 147, 107656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, P.; Cycon, A.; Friedman, L. Seeking social support and postpartum depression: A pilot retrospective study of perceived changes. Midwifery 2019, 71, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accortt, E.E.; Wong, M.S. It Is Time for Routine Screening for Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders in Obstetrics and Gynecology Settings. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2017, 72, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).