Abstract

Background/Objectives: Breastfeeding is widely recognized as the best way to feed infants and has numerous health benefits for both mothers and infants. However, despite its well-documented benefits, breastfeeding rates remain lower than recommended in many parts of the world. This systematic review examines factors that create barriers for mothers trying to breastfeed, covering studies published between 2003 and 2025. Methods: A total of 18 studies were included in this systematic review, selected from the following databases: PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Academic Search Complete, Communication and Mass Media Complete, ERIC, SocINDEX, and CINAHL. Studies were selected based on predefined inclusion criteria, focusing on peer-reviewed articles that examined factors influencing breastfeeding practices. Data extraction and quality assessment were performed independently by two reviewers using standardized tools. The review analyzed personal, cultural, economic, and health-related barriers. Results: The analysis revealed multiple barriers to breastfeeding, categorized into personal, sociocultural, economic, and healthcare-related factors. Common challenges included a lack of counseling, latching difficulties, insufficient workplace support, and cultural misconceptions. The heterogeneity of study designs posed challenges in synthesizing the findings. Conclusions: More targeted policies and programs are needed to address these barriers and help mothers succeed in breastfeeding. Improving breastfeeding outcomes worldwide will require better healthcare, social support, and an understanding of cultural influences.

1. Introduction

Breastfeeding is endorsed by the World Health Organization [1] as the optimal feeding practice for infants. Exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life is not only recommended but also associated with numerous health benefits, including reduced infant mortality, improved immune function, and reduced risk of chronic disease. However, while the benefits are well documented, actual breastfeeding success rates do not always match recommendations. According to the WHO, less than 50% of infants worldwide are exclusively breastfed for the first six months, with significant regional variations. For example, increases in both exclusive and any breastfeeding at six months have been observed across regions and income groups, while increases in formula consumption have been observed in upper-middle-income countries [2]. These variations highlight the complex interplay of factors influencing breastfeeding practices.

In this scenario, many mothers may face significant challenges in their willingness to initiate or continue breastfeeding. Among these challenges, changing roles in women’s lives play a crucial role, particularly in relation to work [3]. In most societies, women are expected to fulfill traditional roles related to childcare and household responsibilities while participating in the labor force. Despite limited data, breastfeeding rates after returning to work average 25% and vary widely around the world [4]. While economic factors play a role, cultural influences strongly shape policies and workplace support.

In addition, cultural beliefs and societal stereotypes strongly influence breastfeeding decisions [5]. In some cultures, breastfeeding in public is still stigmatized, discouraging mothers from practicing it outside the home. In contrast, some traditions promote formula feeding as a sign of modernity or affluence, leading many mothers to choose formula feeding despite being aware of the benefits of breastfeeding. A narrative analysis study conducted in the United Kingdom [6] examined the factors influencing the breastfeeding experience of first-time mothers. The authors identified two distinct groups: those who stopped breastfeeding earlier than intended (referred to as disappointed mothers) and those who continued breastfeeding despite challenges. These findings highlight how breastfeeding is not just an individual choice but is shaped by external influences, including cultural expectations, healthcare systems, and workplace policies. From a feminist perspective, this underscores the need for policies that both support breastfeeding and respect a woman’s right to choose without guilt or social judgment [7].

Family dynamics and access to accurate health information also influence breastfeeding decisions [8,9]. Studies suggest that women who receive strong family support, particularly from their partners and close relatives, are significantly more likely to breastfeed. In contrast, misinformation from family members or a lack of appropriate guidance from health professionals can discourage mothers from initiating breastfeeding or cause them to discontinue breastfeeding prematurely [10,11,12]. In some cases, the promotion of skin-to-skin contact and the immediate initiation of breastfeeding contribute to higher breastfeeding rates [13].

Finally, but no less importantly, in the global promotion of a “breastfeeding culture”, research has largely overlooked fathers’/partners’ perspectives on their role in breastfeeding. Existing studies focus on their support for mothers and their attitudes toward breastfeeding but rarely explore their own experiences [14]. Breastfeeding offers significant health benefits for both infants and mothers. Despite global health recommendations advocating for exclusive breastfeeding during the first six months of life, many regions continue to experience suboptimal breastfeeding rates. Various factors contribute to this issue, including personal, sociocultural, economic, and healthcare-related barriers. While some research has explored programs involving fathers and partners, these studies primarily focus on enhancing breastfeeding promotion rather than deeply understanding the specific roles these individuals play in breastfeeding practices. This systematic review aims to examine the main barriers to breastfeeding by synthesizing evidence from studies published between 1995 and 2025, providing a comprehensive understanding of the factors that influence breastfeeding behaviors. By identifying and addressing these barriers, policymakers and healthcare providers can develop targeted interventions to improve breastfeeding success rates worldwide.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Question

This study employs a systematic review in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) [15] guidelines to systematically identify, appraise, and synthesize peer-reviewed literature that investigates the neural mechanisms that influence the perception of antagonistic characters. The PECO (population, exposure, comparator, outcome) framework was used to structure the research question and guide the study selection process. This systematic approach ensured a clear and objective assessment of the evidence related to barriers influencing breastfeeding attitudes and their impact on breastfeeding prevalence and success.

- Population (P): New mothers, breastfeeding.

- Exposure (E): Barriers influencing attitudes toward breastfeeding, including sociocultural norms, workplace policies, healthcare support, misinformation, and stigma.

- Comparator (C): This was considered optional. The comparator included situations where these barriers were absent or had a reduced impact, allowing for a comparison of breastfeeding outcomes in different environments.

- Outcome (O): The primary outcomes analyzed were breastfeeding prevalence, exclusive breastfeeding rates, breastfeeding success, initiation, continuation, and overall outcomes.

Based on the study design and the PECO framework, the research question could be formulated as “What are the key barriers influencing attitudes toward breastfeeding among new mothers, and how do these barriers impact breastfeeding prevalence, success, and continuation?” The review is registered in PROSPERO (2024) under the reference number CRD42024538998.

2.2. Search Strategy

To identify relevant studies, a literature search was conducted in EBSCOhost, including all its available databases, ensuring a broad and interdisciplinary approach to neuroscientific and narrative-related research. The search was performed using the following Boolean search syntax:

(“infant nutrition” OR “breastfeeding” OR “new mothers” OR “lactating women”) AND (“barriers” OR “challenges” OR “obstacles” OR “attitudes” OR “difficulties” OR “stigma” OR “social influences” OR “workplace” OR “cultural” OR “health support”) AND (“breastfeeding prevalence” OR “exclusive breastfeeding rates” OR “breastfeeding success” OR “breastfeeding initiation” OR “breastfeeding continuation” OR “breastfeeding outcomes”).

The following EBSCOhost databases were included in the search: (i) PsycINFO; (ii) MEDLINE; (iii) Academic Search Complete; (iv) Communication and Mass Media Complete; (v) ERIC; (vi) SocINDEX; and (vii) Cinahl.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This systematic review includes studies focusing on new mothers or lactating women and the barriers, challenges, or influencing factors affecting breastfeeding covering studies published between 2003 and 2025. Eligible studies must report on breastfeeding prevalence, exclusive breastfeeding rates, breastfeeding success, initiation, continuation, or related outcomes. Peer-reviewed quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies, as well as systematic reviews and meta-analyses, are considered. To ensure relevance, only studies published within the last 30 years are included. The review considers research conducted in diverse cultural and socioeconomic settings and published in English or other specified languages.

Studies are excluded if they focus on pregnant women, non-lactating individuals, or unrelated populations such as fathers or healthcare providers. Research that does not specifically examine breastfeeding barriers or lacks relevant outcomes is also excluded. Additionally, opinion pieces, editorials, conference abstracts, and low-quality studies are not considered. Articles published more than 30 years ago are excluded unless they provide essential background knowledge.

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

Two independent reviewers screened the results. In cases where there was disagreement regarding the inclusion of a study (four conflicting cases), a third independent reviewer was consulted to make the final decision. To facilitate the screening process and enhance the rigor and efficiency of the systematic review, Rayyan software (https://new.rayyan.ai/ accessed on 22 March 2025) was employed. In this way, and after conducting the database search, all retrieved articles were screened for relevance based on their title and abstract, with only those meeting the inclusion criteria advancing to a full-text review. During this process, key data were systematically extracted and analyzed, including study details (authors, year, and journal), sample size and demographics (age, gender, and participant characteristics), and breastfeeding-related factors (barriers, cultural influences, workplace policies, and healthcare support).

2.5. Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

Risk of bias and methodological quality were assessed using a structured adaptation of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS), specifically tailored for the appraisal of observational studies in breastfeeding research. This modified tool evaluated selection bias, methodological rigor, and statistical appropriateness and has been previously used in similar systematic reviews. Studies were categorized as having low, moderate, or high risk of bias based on consensus by two independent reviewers

3. Results

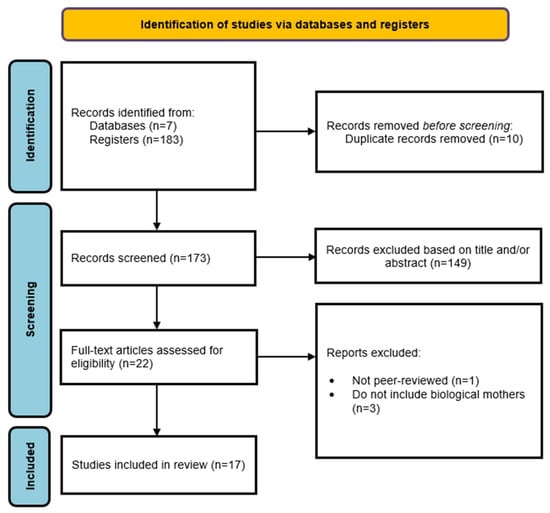

Figure 1 presents the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram, which illustrates the step-by-step screening process that led to the inclusion of 17 studies in the review. The diagram provides a comprehensive overview of the selection process, starting with the total number of records initially identified through systematic searches across multiple electronic databases. This initial pool reflects the breadth of sources consulted to ensure a wide coverage of relevant literature. Following this, the diagram indicates the number of duplicate records that were identified and subsequently removed to avoid redundancy in the analysis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for systematic review: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion of studies in the current study.

The next stage presented in the diagram is the screening of titles and abstracts, where records were assessed against the predefined eligibility criteria. At this point, studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded, narrowing down the pool to the most relevant publications. The diagram then moves on to the full-text review stage, showing how many studies were retrieved and evaluated in depth for eligibility. It also specifies the number of studies excluded at this stage, accompanied by explicit reasons for their exclusion (e.g., methodological limitations, irrelevant outcomes, or insufficient data). Finally, the flow diagram highlights the number of studies that successfully met all inclusion criteria and were incorporated into the systematic review. This visual representation not only clarifies the rigorous selection process but also enhances transparency, allowing readers to understand how the final sample of studies was determined and ensuring the replicability of the review process.

Table 1 presents an overview of the 17 studies included in this systematic review, summarizing key details such as the main goals, methodologies, and outcomes of each study. This table allows for a quick comparison of the research objectives and approaches as well as the primary findings related to breastfeeding barriers and outcomes.

Table 1.

Manuscripts included in the review.

More precisely, multifactorial barriers to breastfeeding across diverse contexts and populations were identified. Key challenges identified include clinical and physiological barriers, such as biomechanical sucking difficulties in infants [16] and delayed lactogenesis among mothers of preterm infants [19]. Structural and workplace-related obstacles are also prominent, exemplified by the difficulties faced by mothers in healthcare settings, where inadequate lactation spaces, a lack of protected time, and unsupportive institutional cultures hinder breastfeeding continuation [27,30]. In addition, sociocultural barriers emerge as significant factors, including the absence of partner or family support, negative attitudes toward public breastfeeding, and the stigma associated with certain practices, such as exclusive formula feeding among HIV-positive women [25,32]. Collectively, these findings highlight the complex, interconnected nature of breastfeeding barriers, underscoring the need for comprehensive interventions at clinical, social, and structural levels to promote and sustain breastfeeding in varied settings.

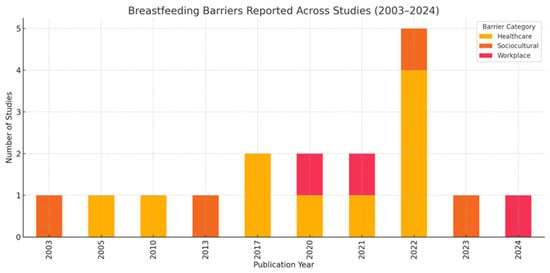

Figure 2 depicts the barriers to breastfeeding across a 10-year scale, categorized by barrier type (healthcare, sociocultural, workplace), based on the studies reviewed.

Figure 2.

Manuscripts included in the review on a 10-year scale classified by category (healthcare, sociocultural, and workplace).

Table 2, on the other hand, focuses on assessing the risk of bias in the studies included in the review. This table evaluates the methodological quality of each study, considering factors such as sample size, study design, and potential sources of bias.

Table 2.

Risk of bias.

4. Discussion

Breastfeeding is widely recognized for its health benefits to both infants and mothers. However, despite global recommendations, breastfeeding rates remain suboptimal in many regions. This systematic review explores the barriers to breastfeeding, categorizing them into personal, sociocultural, economic, and healthcare-related factors. By analyzing peer-reviewed literature, this review identifies common challenges that hinder breastfeeding initiation and continuation.

A common theme across the studies is the influence of maternal health, infant conditions, and external factors like healthcare practices and social support on breastfeeding success. For example, the study by Herzhaft-Le Roy et al. [16] found significant improvements in sucking ability with osteopathic treatment, indicating the potential for non-pharmacological interventions in managing breastfeeding issues. However, other studies [18,26] revealed that while interventions may help to a degree, issues like poor breastfeeding technique or delayed lactogenesis remain persistent challenges for many mothers.

Specific risks highlighted include a lack of counseling and support from healthcare professionals, which can lead to difficulties in initiating and maintaining breastfeeding. For instance, inadequate lactation counseling has been associated with the early cessation of breastfeeding due to unresolved latching issues and maternal concerns about milk supply. Additionally, workplace-related challenges, such as insufficient maternity leave, a lack of private spaces for breastfeeding, and inflexible work schedules, have been identified as significant barriers that contribute to the early discontinuation of breastfeeding among employed mothers.

The studies also shed light on the sociocultural and psychological barriers to breastfeeding, with significant findings in research by Toro, Obando, and Alarcón [32] and Garti et al. [20] highlighting the critical role of social support networks in maintaining breastfeeding. In contrast, the challenges of maternal guilt and work-life balance, as seen in Moulton et al. [26] and Peters et al. [29], suggest that societal expectations and workplace policies significantly affect breastfeeding practices. Similarly, the increasing use of virtual lactation support, explored by different authors [8,24], reveals a shift in how breastfeeding guidance is delivered, particularly in the context of COVID-19, yet the effectiveness of such services requires further evaluation due to their limitations in providing hands-on assistance.

Results were also organized by barrier category (healthcare-related, sociocultural, workplace-related) and publication year. Healthcare-related barriers were consistently reported across the entire time frame, reflecting their persistent influence on breastfeeding outcomes. Sociocultural barriers appeared intermittently, with an increase in recent years, suggesting growing recognition of the role of social support, cultural norms, and stigma. Workplace-related barriers were predominantly reported in studies published after 2010, aligning with increasing research attention to maternal employment and lactation challenges in professional settings. This temporal visualization highlights both the enduring and emerging challenges mothers face in breastfeeding, underscoring the need for multi-level interventions that address healthcare, workplace, and sociocultural dimensions simultaneously.

The studies under review also highlight the importance of addressing lactation problems in specific populations, such as mothers using Assisted Reproductive Technology or those with preterm infants, where breastfeeding challenges were reported to be more severe. For instance, Dong et al. [19] identified that delayed lactogenesis II was prevalent among mothers of preterm infants, which underscores the need for targeted interventions for these high-risk groups.

In terms of study quality, most of the included studies were subject to a moderate risk of bias, particularly due to sample size and methodological limitations. Some studies, like [21,24], had less bias and stronger data, making their conclusions more trustworthy. This variability in study quality emphasizes the need for more rigorous research with larger, more diverse samples to ensure the generalizability of findings. Nevertheless, one should bear in mind that the quality assessment used a modified version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, adapted for breastfeeding-related observational studies. While this tool has not undergone formal validation, it allowed for a consistent appraisal of selection and performance bias across heterogeneous study designs.

It should be noted that little attention is given in the literature to the role of partners, particularly in how their support or lack thereof can influence breastfeeding success [14]. The absence of a broader focus on partners’ support and cultural influences leaves a gap in understanding the full spectrum of factors that affect breastfeeding practices.

While this review provides valuable insights into the various challenges and interventions related to breastfeeding, it is not without limitations. Many of the studies included in the review had small, homogenous sample sizes, which limits the generalizability of their findings. The variability in research methodologies, from randomized controlled trials to qualitative interviews further complicates comparisons across studies. Additionally, several studies lacked long-term follow-up, which makes it difficult to assess the sustained impact of interventions. Future research should focus on larger, more diverse populations and employ longitudinal designs to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of breastfeeding interventions. Future research should explore not only interventions but also the mechanisms by which cultural, workplace, and social dynamics shape breastfeeding practices. Hypotheses for future studies might include how integrated workplace policies and paternal involvement affect breastfeeding duration or how combined in-person and virtual support can improve breastfeeding outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review aimed to identify the key barriers influencing breastfeeding attitudes, initiation, and continuation. The findings demonstrate that breastfeeding practices are shaped by multifactorial barriers across personal, clinical, sociocultural, and workplace domains. Healthcare-related challenges, including insufficient counseling and inconsistent lactation support, were among the most pervasive. Sociocultural influences—such as stigma, misinformation, and a lack of partner or family support—also played a significant role. Workplace constraints further compounded these difficulties, particularly among employed mothers.

To improve breastfeeding outcomes, interventions must adopt a multidimensional approach that integrates healthcare reform, workplace accommodations, and culturally sensitive education. Future research should investigate the longitudinal effects of combined in-person and virtual lactation support and examine the impact of partner involvement and workplace policies on breastfeeding duration.

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed equally to this work. A.M.-T., M.P.-B., A.A.-C., C.M.-T. and M.T.M.-L. were involved in the conception, design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of the results, as well as in the writing and revision of the manuscript. The contributions were made in an equitable manner, ensuring that every author played a significant role in the development and completion of the study. As a result, all authors share equal responsibility for the content and conclusions presented. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Catholic University of Valencia San Vicente Mártir for their contribution and help in the payment of the Open Access publication fee.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PECO | Population, Exposure, Comparator, Outcome |

| NOS | Newcastle–Ottawa Scale |

| ART | Assisted Reproductive Technology |

| EFF | Exclusively formula feed |

References

- World Health Organization. Breastfeeding. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Neves, P.A.R.; Vaz, J.S.; Maia, F.S.; Baker, P.; Gatica-Domínguez, G.; Piwoz, E.; Rollins, N.; Victora, C.G. Rates and time trends in the consumption of breastmilk, formula, and animal milk by children younger than 2 years from 2000 to 2019: Analysis of 113 countries. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health. 2021, 5, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, R.S.; Sulaiman, Z.; Nik Hussain, N.H.; Mohd Noor, N. Working mothers’ breastfeeding experience: A phenomenology qualitative approach. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutheil, F.; Méchin, G.; Vorilhon, P.; Benson, A.C.; Bottet, A.; Clinchamps, M.; Barasinski, C.; Navel, V. Breastfeeding after Returning to Work: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2021, 18, 8631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beggs, B.; Koshy, L.; Neiterman, E. Women’s Perceptions and Experiences of Breastfeeding: A scoping review of the literature. BMC Public. Health. 2021, 21, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, G.; Ingram, J.; Clarke, J.; Johnson, D.; Jolly, K. Who Gets to Breastfeed? A Narrative Ecological Analysis of Women’s Infant Feeding Experiences in the UK. Front. Sociol. 2022, 7, 904773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinones, C. “Breast is best”… until they say so. Front. Sociol. 2023, 8, 1022614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.S.; Li, K.M.C.; Li, K.Y.C.; Beake, S.; Lok, K.Y.W.; Bick, D. Relatively speaking? Partners’ and family members’ views and experiences of supporting breastfeeding: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2021, 376, 20200033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matriano, M.G.; Ivers, R.; Meedya, S. Factors that influence women’s decision on infant feeding: An integrative review. Women Birth. 2022, 35, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojantausta, O.; Pöyhönen, N.; Ikonen, R.; Kaunonen, M. Health professionals’ competencies regarding breastfeeding beyond 12 months: A systematic review. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2023, 18, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orchard, L.J.; Nicholls, W. A systematic review exploring the impact of social media on breastfeeding practices. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 6107–6123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verduci, E.; Vizzuso, S.; Frassinetti, A.; Mariotti, L.; Del Torto, A.; Fiore, G.; Marconi, A.; Zuccotti, G.V. Nutripedia: The Fight against the Fake News in Nutrition during Pregnancy and Early Life. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dueñas-Espín, I.; León Cáceres, Á.; Álava, A.; Ayala, J.; Figueroa, K.; Loor, V.; Loor, W.; Menéndez, M.; Menéndez, D.; Moreira, E.; et al. Breastfeeding education, early skin-to-skin contact and other strong determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in an urban population: A prospective study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e041625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- deMontigny, F.; Gervais, C.; Larivière-Bastien, D.; St-Arneault, K. The role of fathers during breastfeeding. Midwifery 2018, 58, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzhaft-Le Roy, J.; Xhignesse, M.; Gaboury, I. Efficacy of an Osteopathic Treatment Coupled With Lactation Consultations for Infants’ Biomechanical Sucking Difficulties. J. Hum. Lact. 2017, 33, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelladurai, R.; Gopinath, P.P.; Devi, G.; Vaithianathan, H. Challenges of Lactation and Breastfeeding among mothers conceived through art—A Questionnaire Based Survey. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 3, e470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, L.D.; Giugliani, E.R.; do Espírito Santo, L.C.; França, M.C.; Weigert, E.M.; Kohler, C.V.; de Lourenzi, B.A.L. Effect of intervention to improve breastfeeding technique on the frequency of exclusive breastfeeding and lactation-related problems. J. Hum. Lact. 2006, 22, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.; Ru, X.; Huang, X.; Sang, T.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Feng, Q. A prospective cohort study on lactation status and breastfeeding challenges in mothers giving birth to preterm infants. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2022, 17, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garti, H.; Bukari, M.; Wemakor, A. Early initiation of breastfeeding, bottle feeding, and experiencing feeding challenges are associated with malnutrition. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 5129–5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadiri, F.; Iranpour, N.; Yunesian, M.; Shadlou, Z.; Kaviani, A. Do the different reasons for lactation discontinuation have similar impact on future breast problems? Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013, 14, 6147–6150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Hamid, H.B.; Szatkowski, L.; Budge, H.; Ojha, S. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on breastfeeding during and at discharge from neonatal care: An observational cohort study. Pediatr. Investig. 2022, 6, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.H.; Henebury, M.J.E.; Arentsen, C.M.; Sriram, U.; Metallinos-Katsaras, E. Facilitators, Barriers, and Best Practices for In-Person and Telehealth Lactation Support During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nurs. Womens Health 2022, 26, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacCarthy, S.; Rasanathan, J.J.; Nunn, A.; Dourado, I. “I did not feel like a mother”: The success and remaining challenges to exclusive formula feeding among HIV-positive women in Brazil. AIDS Care 2013, 25, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Matias, S.L.; Nommsen-Rivers, L.A.; Creed-Kanashiro, H.; Dewey, K.G. Risk factors for early lactation problems among Peruvian primiparous mothers. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2010, 6, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moulton, K.L.; Battaglioli, N.; Sebok-Syer, S.S. Is Lactating in the Emergency Department a Letdown? Exploring Barriers and Supports to Workplace Lactation in Emergency Medicine. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2021, 78, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulton, K.L.; Izuno, S.A.; Prendergast, N.; Battaglioli, N.; Sebok-Syer, S.S. Alleviating stressfeeding in the emergency department: Elucidating the tensions induced by workplace lactation space issues. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2024, 5, e13226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachal, H. A Study to Identify Problems of Lactation Among Postnatal Mothers During Early Post-Partum Period at Selected Hospitals of Bardoli Taluka of Surat District, Gujarat. Nurs. J. India 2021, 112, 283–285. Available online: https://www.tnaijournal-nji.com/admin/assets/article/pdf/9910_pdf.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.W.; Kuczmarska-Haas, A.; Holliday, E.B.; Puckett, L. Lactation challenges of resident physicians- results of a national survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiger, E.R.; Wasser, H.M.; Hutchinson, S.A.; Foster, G.; Sideek, R.; Martin, S.L. Barriers to Providing Lactation Services and Support to Families in Appalachia: A Mixed-Methods Study With Lactation Professionals and Supporters. Am. J. Public Health 2022, 112, S797–S806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, I.; Scott, J.A.; Reid, M. Infant feeding attitudes of expectant parents: Breastfeeding and formula feeding. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 45, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, M.C.; Obando, A.; Alarcón, M. Social valuation of the maternal lactation and difficulties that entails the precocious weaning in smaller infants. Andes Pediatr. 2022, 93, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).