Abstract

Background/Objectives: Different international organizations recommend exclusive breastfeeding during the neonate’s first six months of life; however, figures of around 38% are reported at the global level. One of the reasons for early abandonment is the mothers’ perception of supplying insufficient milk to their newborns. The objective of this research is to assess how mothers’ perceived level of self-efficacy during breastfeeding affects their ability to breastfeed and the rates of exclusive breastfeeding up to six months postpartum. Methods: A systematic review for the 2000–2023 period was conducted in the following databases: Cochrane, Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed, Science Direct, and CINAHL. Original articles, clinical trials, and observational studies in English and Spanish were included. Results: The results comprised 18 articles in the review (2006–2023), with an overall sample of 2004 participants. All studies were conducted with women who wanted to breastfeed, used the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale or its short version to measure postpartum self-efficacy levels, and breastfeeding rates were assessed up to 6 months postpartum. Conclusions: The present review draws on evidence suggesting that mothers’ perceived level of self-efficacy about their ability to breastfeed affects rates of exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months postpartum. High levels of self-efficacy are positively related to the establishment and maintenance of exclusive breastfeeding; however, these rates decline markedly at 6 months postpartum

1. Introduction

Various international organizations support exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) during the newborn’s first six months of life, and subsequently complementing it with food options up to the age of two years or more [1,2,3].

Both for newborns and for breastfeeding (BF) mothers, the benefits of EBF are many and are widely described in the literature [4,5,6]. In addition, it can be pointed out that BF is a key determining factor in promoting public health and reducing inequalities in health [7]. Despite all the above, globally, only 38% of the newborns receive EBF during their first six months of life [4]. The BF rates decrease rapidly during the first weeks postpartum, and it is in the first month that the most noticeable change is found in the number of women who interrupt BF [8].

Demographic, physiological, and psychological factors can interfere both positively and negatively in BF interruption or maintenance [9,10,11,12,13]. Among the psychological factors is the mothers’ perception of supplying insufficient milk to their newborns. Although this condition is usually called hypogalactia, this perception is not always a true case of the condition (non-production of milk resulting from organic factors) but is often due to scarce or non-existent production related to an inadequate BF technique and to the technical aspects of BF (such as latch, position of the newborn and of the mother, etc.). This perception of BF non-efficacy is the most frequent reason for BF abandonment, which makes self-efficacy (SE) an essential factor for EBF initiation [8,14].

A large number of the studies on SE have been based on Albert Bandura’s concept [15,16,17,18]. Dennis adapted this concept to the reproductive field, defining SE regarding EBF as the mother’s self-confidence in her ability to breastfeed her newborn [19]. Since then, maternal SE has received considerable attention as a predictor of health-related behaviors [20,21,22,23] in addition to being a factor that exerts an influence on maternal satisfaction with EBF [24].

In relation to the interventions performed, several programs have been developed in an attempt to increase maternal breastfeeding self-efficacy (BSE), mainly targeted at mothers at high risk of EBF abandonment in the first weeks postpartum [11,25,26].

The aim of the review is to assess how mothers’ perceived level of self-efficacy during breastfeeding affects their ability to breastfeed and the rates of exclusive breastfeeding up to six months postpartum.

2. Materials and Methods

A systematic literature review was conducted according to the guidelines established by the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) (Supplementary Table S1) [27], using qualitative literature synthesis. A detailed protocol outlining the methodology and search strategies used in this review has been published on Preprints.org (DOI: https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202411.1098.v1)

Table 1 shows the PICO criteria (participants, intervention, comparison, and outcomes) used for the inclusion of studies.

Table 1.

PICO Criteria.

2.1. Search Strategy

A search of the literature from January 2000 to December 2023 was conducted. The systematic literature search was conducted in the following electronic databases: Cochrane, Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, PubMed, Science Direct, and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL).

The designed search strategy was conducted by combining the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and Descriptors in Health Sciences thesaurus with free terms as synonyms of the descriptors in the literature, through the use of AND and OR Boolean operators. The MeSH term employed was “self-confidence”, and those for DeCS were “self-efficacy”, “breastfeeding”, “lactation”, and “exclusive breastfeeding”. The free terms chosen were the following: “self-reliance” and “breastfeeding rate” (Table 2).

Table 2.

Search strategy in the databases.

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) clinical trials or observational studies published in English and/or Spanish, (2) the subjects studied were postpartum women in whom the variable SE in their ability to breastfeed was present or, in its absence, related terms were used as synonyms, (3) SE was measured using a validated tool, (4) the influence of SE on the rate of EBF was studied, and (5) the studies met the PICO criteria described.

The studies excluded were studies not published in English or Spanish, studies carried out with puerperal women with any disease during pregnancy or puerperium (diabetes, pre-eclampsia, etc.), studies carried out with preterm newborns, studies that did not assess variable SE or EBF rates, and studies that did not meet all the PICO criteria.

2.3. Data Extraction

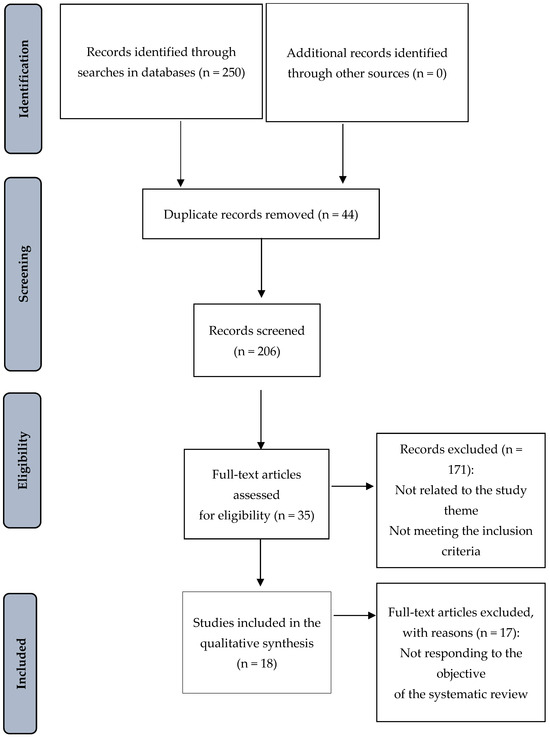

The article selection process began with the paired search conducted by two of the authors. The eligible studies retrieved from the six bibliographic databases (n = 250 records) were imported into the Mendeley® bibliographic reference manager (version 2.126.0) and duplicates were removed (n = 44). The search in the gray literature did not yield relevant results. The pre-selected records (n = 206) were examined in two stages. As a first step, the titles and abstracts were evaluated considering eligibility regarding the inclusion criteria defined according to the PICO framework, eliminating n = 171 records. Secondly, the remaining full-text articles that were selected (n = 35) were thoroughly read to evaluate their inclusion in the review. Once the eligibility process was complete, another two authors assessed the methodological quality and the biases of the potentially useful studies; this improved the screening of the results to obtain more complete and relevant information, thus enhancing the quality of the study. The degree of agreement between both researchers in terms of evaluating eligibility of the studies was assessed using Kappa’s statistical test, with high agreement indicated (Kappa statistics = 0.85). The articles excluded were those that did not meet all the inclusion criteria, did not respond to the review objective, or were focused on studying any variable other than SE regarding ability to breastfeed (n = 17). Finally, the set of articles included in the current systematic review amounted to a total of 18 records. The PRISMA flow diagram is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram corresponding to the selection of articles according to PRISMA.

2.4. Data Analysis

The tool described by López de Argumedo et al. [28] for systematic reviews was used to assess the quality level and evaluate the risk of bias in the studies (Supplementary Table S2). This tool appraises six areas to assess the quality of the evidence contributed by each study included. Its purpose is to provide a structured and standardized way to identify limitations in the studies included in a review, in order to improve the interpretation of the findings and assess the strength of the scientific evidence. A narrative synthesis of the data was undertaken. From each study, we extracted general data, the assessment made by the authors, and key findings in reference to the objective of the review.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

Of the total of 18 studies included, 13 (72.2%) were conducted in Asia, 4 (22.2%) in North America, and 1 in Europe (5.6%); 72.22% were experimental studies and 27.8% area observational studies.

All the studies were conducted with women who wanted to breastfeed, with sample sizes varying from 30 to 781, accounting for a total of 5771 participants in the 18 studies included. Eleven studies (61.1%) included only primiparous women while in the other seven (38.9%), the participants were primiparous and multiparous women.

The author, date of publication, study aim, sample, and design of the studies included in the review are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Author, date of publication, study aim, sample, and design of the studies included in the review.

All the detailed and relevant information for data analysis, synthesis, and interpretation was collected, encompassing the following: bibliographic data, country, study design, tool used to assess SE, evaluation of the EBF rates, main results, and quality level of each study (Table 4 and Table 5).

Table 4.

Characteristics of the articles included in this review (experimental studies).

Table 5.

Characteristics of the articles included in this review (observational studies).

3.2. Measuring Instruments and Interval

To assess levels of self-efficacy, all 13 studies reviewed in this study used the BSES [32,39,40,44] or BSES-SF [26,29,30,31,34,35,38,41,43]. The BSES was created by Dennis and Faux in 1999 to assess confidence in breastfeeding [45]. This self-administered tool consists of 33 items, all preceded by the phrase “I can always”, and is rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all confident) to 5 (very confident). Higher scores indicate greater levels of breastfeeding self-efficacy. In 2003, Dennis reduced the BSES from 33 to 14 items and renamed it the BSES-SF [46]. There is substantial evidence supporting the reliability and validity of this version as a global measure of breastfeeding self-efficacy. The reliability and validity of this instrument have been found satisfactory in different countries and populations [26,47,48,49,50,51,52].

The SE levels and the EBF rates were evaluated at different points during the postpartum period: early postpartum, 1 month postpartum (4 weeks), 2 months postpartum (8 weeks), 3 months postpartum (12 weeks), and 6 months postpartum [23,26,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44].

Table 6 shows the author, date of publication, variables measured, instruments, reliability, and validity of the instruments of the studies included in the review.

Table 6.

Author, date of publication, variables measured, instruments, reliability, and validity of the instruments of the studies included in the review.

3.3. Quality Assessment

The results of the analysis carried out according to the tool described by López de Argumedo et al. [28], in relation to the evaluation of methodological quality, are presented in Supplementary Table S3.

3.4. Self-Efficacy Levels Perceived by the Mothers About Their Ability to Breastfeed

The difference between the two scales is that the BSES consists of 33 items with a maximum score of 165 points, and the BSES-SF consists of 14 items with a maximum score of 70 points [45,46].

In the studies that used BSES, the scores were 105.28 points at 6 months postpartum (IG) in the study by Ansari et al. [32], 121.44 points at 6 months postpartum (IG) in Shariat et al. [39], and 141.44 points at 2 months postpartum (IG) in Yesil et al. [44].

Regarding the other studies that used BSES-SF, the early postpartum scores were as follows: 34.8 points (IG) in the study by Awano and Shimada [30], 51.6 points in Otsuka et al. [34], 55.89 points (IG) in Chan et al. [26], 46.2 points (IG) in Tseng et al. [41], 63.66 points (IG) in Vakilian et al. [40], and 43.05 points (IG) Wong and Chien [43].

At 1 month postpartum, the scores were 59 points in McQueen et al. [31], 53.38 points in Noel-Weiss et al. [29], 53.5 points in Otsuka et al. [34], 58.8 points in Wu et al. [35], and 48.1 points (IG) in the study by Tseng et al. [41].

At 2 months postpartum, the scores were 62.46 points in the study by Araban et al. [38] and 59.85 points in that by Wu et al. [35]. At 3 months postpartum, the score in the study by Tseng et al. was 49 points (IG) [41]. At 6 months postpartum, the scores were 49.9 points (IG) in the study by Awano and Shimada [30] and 46.7 points (IG) in Tseng et al. [41].

3.5. Self-Efficacy and Exclusive Breastfeeding Rates

The study with the largest sample included in the current review (781 women) was a clinical trial conducted by Otsuka et al. [34] in Japan. This study evaluated the early postpartum EBF rates and those at 4 weeks and at 12 weeks. Early postpartum, the EBF rate was 88% (mean of both groups). However, at 4 weeks postpartum, the EBF rates were higher in the women whose maternal self-efficacy levels increased (IG) than in the other groups; 73.4% maintained EBF in the group, with the highest score (53.5 points in BSES-SF). Despite this, the EBF rates presented a marked reduction at 12 weeks postpartum, falling to 47%, and the study argued that the intervention was therefore not effective in increasing or maintaining the SE levels at 12 weeks postpartum.

In this same line, Shariat et al. [39] evaluated EBF rates early postpartum and at 6 months postpartum, reporting that they dropped from 87.5% to 40.9% between early postpartum and 6 months postpartum in the IG, and from 75.4% to 23.5% in the CG. The difference in the percentages of BF rates lay in the SE levels: in the IG, the BSES scores increased after one month of intervention, up to 20 points more than in the CG. Despite that, the mean BSES scores at 6 months were similar (121.44 vs. 122.52). The variable that marked the difference was “anxiety” (which is not studied in this review): higher anxiety levels were related to lower SE levels, and the mothers in the IG presented lower anxiety levels. As in the aforementioned study [34], the EBF rates at 6 months were markedly reduced compared with early postpartum and the first postpartum weeks, and maternal SE levels were one of the factors that exerted a notable influence.

Unlike the previous studies, an intervention study performed by Ansari et al. [32] to improve SE showed that the increase in BSE sustained high EBF rates over time, with 73.3% at 6 months postpartum.

In the study by Awano and Shimada [30], which involved a sample consisting exclusively of primiparous women (which can exert an influence on the results because of the lack of previous BF experience, compared with other studies that included multiparous women), the maternal SE levels exerted a major impact on the EBF rates at 4 weeks postpartum. In that study, the early postpartum EBF rates were 90% in the IG and 89% in the CG; however, they remained at 90% in the IG at 1 month postpartum and dropped to 65% in the CG, with the SE levels also increasing in the IG throughout this period. The SE levels at 1 month postpartum were higher in the IG than in the CG (49.9 vs. 46.5 points on the BSES-SF, respectively).

However, in the study by Wu et al. [35], which was also conducted with primiparous women, the EBF rates were only 60% at 8 weeks postpartum in both groups, although the BSES-SF scores were similar to those found in Awano and Shimada [30]. The main cause was the mothers’ perception of supplying insufficient milk to their newborns. Nevertheless, higher SE levels were associated with EBF maintenance.

Other factors, such as maternal educational level or the mothers’ previous BF experience, are not addressed in the current review; however, it is necessary to take them into account in future studies, as they also exert an influence on EBF rates.

Two of the most recent studies included—Tseng et al. [41] and Vakilian et al. [40]—conducted randomized controlled trials with primiparous mothers. Vakilian et al. [40] evaluated EBF rates only at 1 month postpartum, obtaining 89.2% in the IG (63.66 points on the BSES-SF) and only 55.5% in the CG (57.04 points on the BSES-SF). The positive impact of the interventions on maternal SE levels during the first weekz postpartum is consistent with the results found by Otsuka et al. [34] and by Shariat et al. [39]. In these studies, the same results were not obtained in the subsequent weeks: although the mothers’ SE levels were maintained, the rates were markedly reduced.

This was also the case in the study by Tseng et al. [41]. After the intervention, the study determined the EBF rates at four time points: early postpartum and at 1, 3, and 6 months postpartum. The EBF rates were higher in the IG compared with the CG, although they varied in both groups at the different time points studied. The differences in the EBF rates were reflected in the BSES-SF scores, with a mean of 48 points in the IG versus 40 points in the CG. Another study, by Chan et al. [26], where the EBF rates were assessed early postpartum and at 1, 2, and 6 months postpartum, showed similar results to those of the previous study. The EBF rates presented a marked reduction at 6 months postpartum: 40%, 37.2%, 31.4%, and 11.4%, respectively, in the IG with a mean score of 50 points on the BSES-SF, and 22.2%, 13.9%, 5.5%, and 5.6% in the CG with a mean score of 40 on the BSES-SF.

In the study conducted by Wu et al. [23], only 25% of the participants reported BF during their postpartum hospitalization, a percentage much lower than that reported in previous studies, although the study also established a significant relationship between SE and EBF rates. In the oldest study, by Noel-Weiss et al. [29], EBF rates at 8 weeks were maintained at 64%, which correlated with the increase in SE levels in both groups.

Finally, the two most recent studies were by Wong and Chien [43] and Yesil et al. [44] (2023). In the study by Yesil et al. [44], there were significant differences in EBF rates, with 72.5% in the IG providing EBF at birth compared with only 30% in the CG.

In a study during the COVID-19 pandemic in China [43], where SE scores were low (43.05 points on the BSES-SF), only 53–54% of mothers gave EBF at 2 months postpartum.

4. Discussion

This systematic review assessed how mothers’ perceived levels of self-efficacy during breastfeeding affect their ability to breastfeed and their rates of EBF up to six months postpartum. It is necessary to take into account the demographic and cultural characteristics of mothers that may influence breastfeeding, whether they are primiparous or multiparous, and whether or not they have previous breastfeeding experience. It should also be remembered that exceptional situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic may create additional difficulties in promoting BF.

The instruments used to perform the SE measurements in the articles included in the current review [26,29,30,31,32,34,35,38,39,40,41,42,43] are among the most frequently employed in the international scientific community, showing homogeneity in the conceptualization of development, content, construction, and predictive validity [53]. It is indeed a reality that certain disparities were observed in the measurement intervals of the studies reported, which may hinder interpretation of how SE evolved during the postpartum period.

The SE levels reported in the articles reviewed [26,29,30,31,32,34,35,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] showed scores in line with what has been described in the literature in terms of all their measurements; we can compare them to the study conducted by Degrange et al. [20] where the threshold score for BSES was defined at 116/165, which would be equivalent to 49/70 in BSES-SF.

Several publications [26,30,32,34,35,38,39,40,41,42] have used two groups to study the impact of maternal SE on the ability to maintain EBF. The results showed that pregnant women with less SE in their ability to breastfeed presented significantly more chances of interrupting it [34,39,40,41,42].

Ansari et al. [32] reported a significant relationship between SE and the duration of EBF. SE is a modifiable variable that can be improved through the implementation of appropriate programs, but factors such as gestational age and maternal education level must be taken into account. Another intervention conducted in Iran [38] agreed with Ansari et al. [32] that interventions that help increase SE levels can improve EBF rates.

In the intervention conducted by Wu et al. [35] in China, EBF rates were below 60% at 4 and 8 weeks postpartum in both groups, despite having SE scores similar to those in other studies such as Awano and Shimada [30]. The main reasons were maternal perception of insufficient milk supply, lack of family support, and the limited knowledge of professionals regarding breastfeeding. Regardless of the interventions’ effectiveness, these cultural considerations influence SE levels in China and, consequently, EBF outcomes. This may be a differentiating factor compared with results from other studies such as Awano and Shimada [30], conducted in a different culture. Cultural aspects of BF also influenced the results of interventions in primiparous women in the studies by McQueen et al. [31] and Noel-Weiss et al. [29]. Nearly half of the mothers intended to breastfeed beforehand, with BF rates remaining around 60–70% at 8 weeks postpartum in both studies. This was correlated with increasing SE levels as the weeks passed.

Otsuka et al. [34] found a positive correlation between maternal SE and EBF rates in hospitals adhering to United Nations and WHO breastfeeding guidelines, compared with those that did not. Women attending hospitals supporting these guidelines had higher SE scores and EBF rates. Increased maternal SE levels generally led to higher EBF rates and duration, though prior BF experience also played a role. The study included both first-time and experienced mothers but did not specifically analyze how prior experience affected the outcomes.

It is crucial to consider cultural variations when analyzing the impact of maternal self-efficacy on breastfeeding, as different cultural contexts can significantly influence beliefs, practices, and the support mothers receive regarding breastfeeding. For example, studies conducted in Asia have shown that educational interventions based on self-efficacy theory have a particularly strong impact on maternal self-efficacy and exclusive breastfeeding rates compared with other cultural contexts, due to the central role of community norms and family support in these societies [54]. These cultural differences not only impact how interventions are implemented but also how mothers interpret and act upon the information received. Additionally, it is important to highlight the distinction between clinical and statistical significance in these studies. While the results show a statistically significant increase in maternal self-efficacy and breastfeeding duration, it is also necessary to interpret the clinical relevance of these changes—specifically, how these results translate into tangible long-term health benefits for both mothers and infants. Including a broader discussion of clinical significance could better contextualize the findings across different cultures and populations.

The most recent studies including primiparous mothers [41,42] showed that EBF rates positively correlated with SE scores. In the most recent study [44], which included both primiparous and multiparous mothers, previous BF experience influenced SE levels and EBF rates. The intervention was effective in boosting SE levels, maintaining EBF rates up to 12 weeks postpartum. An interesting study because it was developed in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic in China [43], the SE scores were low and only half of the mothers gave EBF at 2 months postpartum. The pandemic had negative influences on SE levels and EBF rates because direct contact with mothers was not possible.

Unlike other factors, SE is potentially modifiable with interventions conducted by health professionals [55,56]. Its role as one of the factors positively associated with EBF initiation and duration is acknowledged [21,22] even in premature newborns [25]. In addition, SE has shown an additional positive impact on EBF rates from early postpartum to 6 months postpartum [20,32,36,39,40,55] and has also been identified as a significantly relevant factor for BF in future pregnancies [20].

Meanwhile, maternal education is a key factor in SE and EBF rates, as several studies suggest. Women with higher educational levels tend to exhibit greater perceived self-efficacy, which translates into a higher ability to initiate and maintain exclusive breastfeeding [54]. Additionally, education level may influence how breastfeeding information is interpreted, the capacity to seek support, and decision making during the postpartum period [57,58]. In this sense, formal education provides mothers with cognitive and critical tools that allow them to better handle breastfeeding challenges, facilitating the adoption of healthy practice [54]. However, education is not limited solely to academic training; specific educational interventions on breastfeeding, led by healthcare professionals, play a crucial role in increasing maternal SE, especially in women with fewer formal educational resources [59]. This highlights the need to design and implement inclusive and accessible educational programs for all mothers, addressing their particular needs and promoting successful breastfeeding, regardless of their educational backgrounds [54]. Although the studies reviewed do not deeply analyze this aspect, the data suggest that educational interventions may be essential for improving breastfeeding outcomes in more vulnerable populations [54].

Despite the impact of the interventions on the levels of SE and the rates of EBF at 6 months postpartum, the figures achieved are still insufficient with respect to the WHO [4] criteria, so it is necessary to continue investigating how to increase these rates.

Furthermore, it is the generalization of the included studies (external validity) that the results obtained cannot be extrapolated to the general population because the studies did not cover sufficiently heterogeneous populations (most of the samples come from hospitals in a single city).

5. Conclusions

The SE level in relation to mothers’ ability to breastfeed affects EBF rates up to 6 months postpartum. Consequently, higher SE levels are positively associated with EBF initiation and maintenance. EBF rates are maintained in early postpartum and at 1 month after birth when the breastfeeding SE levels are high. However, despite interventions’ positive impact on EBF rates at 6 months postpartum, even maintaining high SE levels, these rates are markedly reduced during this period and are insufficient in relation to the objectives proposed by the WHO.

Perceived SE in relation to the ability to breastfeed is a modifiable factor, so it is pertinent to identify early mothers who lack this self-confidence in their breastfeeding ability and to implement effective interventions to increase maternal SE levels.

Given the importance of maternal SE in EBF, it is recommended that future research focuses on the development and evaluation of specific interventions aimed at increasing SE levels in BF mothers. These interventions could include training programs that provide information on BF techniques, as well as support groups where mothers can share experiences and receive positive feedback. Additionally, it will be valuable to implement longitudinal studies to assess the impact of these interventions on SE levels and EBF rates, thereby allowing the identification of effective strategies and their adaptation according to the individual needs of mothers. In this way, we can contribute to improving BF outcomes and supporting mothers on their journey toward a successful BF experience.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare12232347/s1, Table S1: PRISMA Checklist; Table S2: Evaluation of the quality of each study; Table S3: Quality assessment corresponding to each article. References [60,61] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.S. and J.D.G.-S.; methodology, S.S.S. and J.D.G.-S.; formal analysis, S.S.S. and J.D.G.-S.; investigation, S.S.S., J.D.G.-S., I.R.-G., F.L.-L., E.A.-D., and R.P.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.S. and J.D.G.-S.; writing—review and editing, S.S.S., J.D.G.-S., I.R.-G., F.L.-L., E.A.-D., and R.P.-C.; project administration, J.D.G.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e827–e841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union Project on Promotion of Breastfeeding in Europe. Protection, promotion and support of breast-feeding in Europe: A blueprint for action (revised). Public Health Nutr. 2008, 8, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Exclusive Breastfeeding for Six Months Best for Babies Everywhere. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2011/breastfeeding_20110115/en/ (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Organización Mundial de la Salud (WHO). Metas Mundiales de Nutrición 2025: Documento Normativo Sobre Lactancia Materna. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255731/WHO_NMH_NHD_14.7_spa.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 29 July 2021).

- Chowdhury, R.; Sinha, B.; Sankar, M.J.; Taneja, S.; Bhandari, N.; Rollins, N.; Bahl, R.; Martines, J. Breastfeeding and Maternal Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015, 104, 96–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.; Jackson, J. Breastfeeding Knowledge and Intent to Breastfeed. Clin. Lact. 2016, 7, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entwistle, F.; Kendall, S.; Mead, M. Breastfeeding support—The importance of self-efficacy for low-income women. Matern. Child Nutr. 2010, 6, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Gao, L.L.; Ip, W.Y.; Chan, W.C.S. Predictors of breast feeding self-efficacy in the immediate postpartum period: A cross-sectional study. Midwifery 2016, 41, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Abreu, L.M.; Filipini, R.; Alves, B.D.C.A.; da Veiga, G.L.; Fonseca, F.L.A. Evaluation of Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy of Puerperal Women in Shared Rooming Units. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.S.; Alexander, D.D.; Krebs, N.F.; Young, B.E.; Cabana, M.D.; Erdmann, P.; Hays, N.P.; Bezold, C.P.; Levin-Sparenberg, E.; Turini, M.; et al. Factors Associated with Breastfeeding Initiation and Continuation: A Meta-Analysis. J. Pediatr. 2018, 203, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodt, R.C.M.; Ximenes, L.B.; Oriá, M.O.B. Validação de álbum seriado para promoção do aleitamento materno. Acta Paul. Enferm. 2012, 25, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardine, E.E.; McLellan, J.; Dombrowski, S.U. Is being resolute better than being pragmatic when it comes to breastfeeding? Longitudinal qualitative study investigating experiences of women intending to breastfeed using the Theoretical Domains Framework. J. Public Health 2017, 39, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shiraishi, M.; Matsuzaki, M.; Kurihara, S.; Iwamoto, M.; Shimada, M. Post-breastfeeding stress response and breastfeeding self-efficacy as modifiable predictors of exclusive breastfeeding at 3 months postpartum: A prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vila-Candel, R.; Soriano-Vidal, F.J.; Murillo-Llorente, M.; Pérez-Bermejo, M.; Castro-Sánchez, E. Mantenimiento de la lactancia materna exclusiva a los 3 meses posparto: Experiencia en un departamento de salud de la Comunidad Valenciana. Atención Primaria 2019, 51, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy Mechanism in Human Agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Human Agency in Social Cognitive Theory. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 2, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.L. Theoretical Underpinnings of Breastfeeding Confidence: A Self-Efficacy Framework. J. Hum. Lact. 1999, 15, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dégrange, M.; Delebarre, M.; Turck, D.; Mestdagh, B.; Storme, L.; Deruelle, P.; Rakza, T. Les mères confiantes en elles allaitent-elles plus longtemps leur nouveau-né? [Is self-confidence a factor for successful breastfeeding?]. Arch Pediatr. 2015, 22, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efrat, M.W. Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy and Level of Acculturation among Low-Income Pregnant Latinas. Int. J. Child Health Nutr. 2018, 7, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki-Saghooni, N.; Amel, M.; Karimi, F.Z. Investigation of the relationship between social support and breastfeeding self-efficacy in primiparous breastfeeding mothers. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 33, 3097–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.V.; Chen, S.C.; Liu, H.Y.; Lee, H.L.; Lin, Y.E. Knowledge, Intention, and Self-Efficacy Associated with Breastfeeding: Impact of These Factors on Breastfeeding during Postpartum Hospital Stays in Taiwanese Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awaliyah, S.N.; Rachmawati, I.N.; Rahmah, H. Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy as a Dominant Factor Affecting Maternal Breastfeeding Satisfaction. BMC Nurs. 2019, 18, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockway, M.; Benzies, K.; Hayden, K.A. Interventions to Improve Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy and Resultant Breastfeeding Rates: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Hum. Lact. 2017, 33, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, M.Y.; Ip, W.Y.; Choi, K.C. The Effect of a Self-Efficacy-Based Educational Programme on Maternal Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy, Breastfeeding Duration and Exclusive Breastfeeding Rates: A Longitudinal Study. Midwifery 2016, 36, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepes-Nuñez, J.J.; Urrútia, G.; Romero-García, M.; Alonso-Fernández, S. Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Rev. Española Cardiol. 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar]

- López de Argumedo, M.; Reviriego, E.; Gutiérrez, A.; Bayón, J.C. Actualización del Sistema de Trabajo Compartido para Revisiones Sistemáticas de la Evidencia Científica y Lectura Crítica (Plataforma FLC 3.0); Servicio de Evaluación de Tecnologías Sanitarias del País Vasco; Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Noel-Weiss, J.; Rupp, A.; Cragg, B.; Bassett, V.; Woodend, A.K. Randomized controlled trial to determine effects of prenatal breastfeeding workshop on maternal breastfeeding self-efficacy and breastfeeding duration. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2006, 35, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awano, M.; Shimada, K. Development and evaluation of a self care program on breastfeeding in Japan: A quasi-experimental study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2010, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen, K.A.; Dennis, C.L.; Stremler, R.; Norman, C.D. A pilot randomized controlled trial of a breastfeeding self-efficacy intervention with primiparous mothers. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2011, 40, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.; Abedi, P.; Hasanpoor, S.; Bani, S. The effect of interventional program on breastfeeding self-efficacy and duration of exclusive breastfeeding in pregnant women in Ahvaz, Iran. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2014, 19, 510793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, M.E.; McKearney, K.; Saslaw, M.; Sirota, D.R. Impact of breastfeeding self-efficacy and sociocultural factors on early breastfeeding in an urban, predominantly Dominican community. Breastfeed. Med. 2014, 9, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, K.; Taguri, M.; Dennis, C.L.; Wakutani, K.; Awano, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Jimba, M. Effectiveness of a breastfeeding self-efficacy intervention: Do hospital practices make a difference? Matern. Child Health J. 2014, 18, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.S.; Hu, J.; McCoy, T.P.; Efird, J.T. The effects of a breastfeeding self-efficacy intervention on short-term breastfeeding outcomes among primiparous mothers in Wuhan, China. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 1867–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henshaw, E.J.; Fried, R.; Siskind, E.; Newhouse, L.; Cooper, M. Breastfeeding self-efficacy, mood, and breastfeeding outcomes among primiparous women. J. Hum. Lact. 2015, 31, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ip, W.Y.; Gao, L.L.; Choi, K.C.; Chau, J.P.; Xiao, Y. The Short Form of the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale as a Prognostic Factor of Exclusive Breastfeeding among Mandarin-Speaking Chinese Mothers. J. Hum. Lact. 2016, 32, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araban, M.; Karimian, Z.; Kakolaki, Z.K.; McQueen, K.A.; Dennis, C.L. Randomized controlled trial of a prenatal breastfeeding self-efficacy intervention in primiparous women in Iran. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2018, 47, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariat, M.; Abedinia, N.; Noorbala, A.A.; Zebardast, J.; Moradi, S. Breastfeeding self-efficacy as a predictor of exclusive breastfeeding: A clinical trial. Iran. J. Neonatol. 2018, 9, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- De Roza, J.G.; Fong, M.K.; Ang, B.L.; Sadon, R.B.; Koh, E.Y.L.; Teo, S.S.H. Exclusive breastfeeding, breastfeeding self-efficacy and perception of milk supply among mothers in Singapore: A longitudinal study. Midwifery 2019, 79, 102532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, J.F.; Chen, S.R.; Au, H.K.; Chipojola, R.; Lee, G.T.; Lee, P.H.; Shyu, M.L.; Kuo, S.Y. Effectiveness of an integrated breastfeeding education program to improve self-efficacy and exclusive breastfeeding rate: A single-blind, randomised controlled study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 111, 103770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakilian, K.; Farahani, O.C.T.; Heidari, T. Enhancing Breastfeeding—Home-Based Education on Self-Efficacy: A Preventive Strategy. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.S.; Chien, W.T. A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of an Online Educational Program for Primiparous Women to Improve Breastfeeding. J. Hum. Lact. 2023, 39, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesil, Y.; Ekşioğlu, A.; Turfan, E.C. The effect of hospital based breastfeeding group education given early perinatal period on breastfeeding self-efficacy and breastfeeding status. J. Neonatal Nurs. 2023, 29, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.L.; Faux, S. Development and psychometric testing of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale. Res. Nurs. Health 1999, 22, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.L. The breastfeeding self-efficacy scale: Psychometric assessment of the short form. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2003, 32, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, A.; Penrose, K.; Morrison, C.; Dennis, C.L.; MacArthur, C. Psychometric properties of the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form in an ethnically diverse U.K. sample. Public Health Nurs. 2008, 25, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husin, H.; Isa, Z.; Ariffin, R.; Rahman, S.A.; Ghazi, H.F. The Malay version of antenatal and postnatal breastfeeding self-efficacy scale-short form: Reliability and validity assessment. Malays. J. Public Health Med. 2017, 17, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ip, W.Y.; Yeung, L.S.; Choi, K.C.; Chair, S.Y.; Dennis, C.L. Translation and validation of the Hong Kong Chinese version of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale-short form. Res. Nurs. Health 2012, 35, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarter-Spaulding, D.E.; Dennis, C.L. Psychometric testing of the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form in a sample of Black women in the United States. Res. Nurs. Health 2010, 33, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver-Roig, A.; d’Anglade-González, M.L.; García-García, B.; Silva-Tubio, J.R.; Richart-Martínez, M.; Dennis, C.L. The Spanish version of the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form: Reliability and validity assessment. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubaran, C.; Foresti, K.; Schumacher, M.; Thorell, M.R.; Amoretti, A.; Müller, L.; Dennis, C.L. The Portuguese version of the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form. J. Hum. Lact. 2010, 26, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuthill, E.L.; McGrath, J.M.; Graber, M.; Cusson, R.M.; Young, S.L. Breastfeeding Self-efficacy: A Critical Review of Available Instruments. J. Hum. Lact. 2016, 32, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maleki, A.; Faghihzadeh, E.; Youseflu, S. The Effect of Educational Intervention on Improvement of Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2021, 10, 5522229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chipojola, R.; Chiu, H.Y.; Huda, M.H.; Lin, Y.M.; Kuo, S.Y. Effectiveness of theory-based educational interventions on breastfeeding self-efficacy and exclusive breastfeeding: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 109, 103675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Gallego, I.; Corrales-Gutierrez, I.; Gomez-Baya, D.; Leon-Larios, F. Effectiveness of a Postpartum Breastfeeding Support Group Intervention in Promoting Exclusive Breastfeeding and Perceived Self-Efficacy: A Multicentre Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartle, N.C.; Harvey, K. Explaining infant feeding: The role of previous personal and vicarious experience on attitudes, subjective norms, self-efficacy, and breastfeeding outcomes. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 763–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodou, H.D.; Bezerra, R.A.; Chaves, A.F.L.; Vasconcelos, C.T.M.; Barbosa, L.P.; Oriá, M.O.B. Telephone intervention to promote maternal breastfeeding self-efficacy: Randomized clinical trial. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2021, 15, e20200520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piro, S.S.; Ahmed, H.M. Impacts of antenatal nursing interventions on mothers’ breastfeeding self-efficacy: An experimental study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez de Argumedo, M.; Reviriego, E.; Gutierrez, A. Updating of the Shared Work System for Systematic Reviews of the Evidence and Critical Appraisal (FLC 3.0 Platform). Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality. Technology Assessment Service of the Basque Country. 2017. Available online: https://www.ser.es/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Informe-OSTEBA-FLC-3.0.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2021).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).