Abstract

Aim: To describe the latest scientific evidence regarding community-based interventions performed on patients in need of palliative care worldwide. Introduction and background: Given the rise of chronic diseases, their complexities and the fragility of patients, we are facing around 56.8 million people in need of palliative care. Community-based healthcare, particularly palliative care, can address social inequalities and improve the biopsychosocial health of disadvantaged populations. Therefore, primary care, as the main health referent in the community, has a central role in the care of these patients. Methods: This is an integrative review from January 2017 to June 2022 that follows the PRISMA statement and has been registered in PROSPERO. PubMed, Cuiden, the Web of Science (WoS), Cochrane and LILACS were the five databases searched. The scientific quality assessment of the articles was carried out following the CASPe methodology. Study selection was carried out by two researchers, A.V.L. and J.M.C.T., using the inclusion and exclusion criteria mentioned below. In cases of doubt or discrepancy, a third author (J.R.S.) was consulted. Results: The interventions mentioned in the 16 articles analysed were classified under the following categories: music therapy, laughter therapy, spiritual and cognitive interventions, aromatherapy, interdisciplinary and community-based teams, advance care planning and community, volunteering, telemedicine and care mapping. Example: Educating people to talk about different ethical issues could improve their quality of life and help develop more compassionate cities. Conclusions: We have identified interventions that are easily accessible (laughter therapy, telemedicine or music therapy), simple enough to be carried out at the community level and do not incur high costs. This is why they are recommended for people with palliative care needs in order to improve their quality of life.

1. Introduction

Palliative care is the kind of care that improves the quality of life of patients and their families in a holistic way who are facing problems inherent in incurable diseases. It prevents and relieves suffering through early identification, correct assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial or spiritual [1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there are about 56.8 million people in need of palliative care, but only 14% of them actually receive it [1]. Palliative care needs will continue to rise due to the increase in chronic diseases, an ageing population and new treatments; and also, because these scientific advancements extend life expectancy and, in turn, chronicity. Integrating a sustainable, quality and accessible palliative care system requires working with primary healthcare, community and home care providers, as well as supporting care providers such as family members and community volunteers [1]. Primary care, as the main health referent in the community, has a central role in the care of these patients [2].

Community-based care reduces the number of hospitalisations, increases the quality of care and is satisfying for patients [3]. Moreover, the latest trends focus on preventing complications and promoting people’s autonomy [4,5]. Unfortunately, this type of care is very heterogeneous, as it depends on the zone where one lives, which creates inequalities in access to health resources and increases isolation. These issues can be overcome thanks to community-based care teams, care networks and community resources [3,6]. Community-based healthcare, particularly palliative care, can address social inequalities and improve the biopsychosocial health of disadvantaged populations [6,7].

By means of a new approach towards care, education, training and policy formulation, the community can be empowered through the development of volunteering and service networks that can help these people with palliative care needs [8]. Being close to the community allows primary care and palliative home care teams to detect barriers or needs in the community, and then take steps or implement programmes that can improve the quality of life of people [9].

Article 17 of Law 4/2017, of March 9, on the rights and guarantees of people in the dying process, mentions the importance of providing spiritual and emotional care in the hospital and community environment to caregivers, family members and patients alike. Health centres and institutions will facilitate, at the request of patients, or their representatives or relatives, access to people who can provide spiritual support, highlighting home care that provides comfort to people with palliative care needs [8].

In general, these people live in a community and wish to be at home with their family and next to their neighbours [10]. At times, the family or main caregivers are not capable of giving their relatives adequate support, so they come under physical and emotional strain [11]. Previous studies demonstrate the importance of the support of primary care teams [3,10,12] who are capable of accompanying patients, training and empowering their families by providing resources about care management, and supporting the biopsychosocial needs of the community [13].

In some cities in Spain, there are associations and organizations that carry out interventions in the community, but these are not related to end-of-life or palliative care. This is why we need to identify the existing resources in our area, as well as the different types of community-based interventions (music therapy, laughter therapy, volunteering, etc.) for people with palliative care needs, so we can address those and support them and their families throughout their illness [2].

Community-based palliative care faces several significant challenges. First, resource constraints are a major obstacle. A lack of adequate funding and shortages of essential medical supplies hinder the delivery of quality palliative care. In many areas, interdisciplinary teams lack the necessary equipment to manage complex symptoms, affecting patients’ comfort and quality of life [14,15,16].

Second, geographic disparities complicate access to palliative services. Rural and remote areas often have fewer specialized care providers, forcing patients and their families to travel long distances to receive care, if it is available at all. This can be especially difficult for patients with limited mobility or those in advanced stages of their disease [14,15,16].

Third, staffing shortages are a critical concern. There is a lack of trained palliative care professionals, which increases the workload for the few who are available; this can lead to professional burnout. This situation also limits the ability to provide personalized and appropriate care to all patients in need [14,15,16]. These challenges highlight the need for research and policies that address these gaps, improve funding, and encourage the training and equitable distribution of the palliative health workforce.

As mentioned above, the global prevalence of palliative care needs is increasing, and the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that, annually, more than 56.8 million people need palliative care, including 25.7 million people in the last year of life [1]. As is well known, providing interventions to people in need of palliative care improves the quality of life for individuals and families. It is necessary to know what palliative care interventions are being developed in the community, as this would help to optimize the resources available in society and provide solid evidence to guide policy and clinical practice. In fact, few studies have been carried out in this area.

The aim of the present study was to identify community-based interventions on patients in need of palliative care in order to improve palliative care in the community and make use of the resources available around a town in the Albacete region (Spain).

2. Methods

2.1. Design and Sources of Information

An integrative review benefits a systematic review of community-based interventions in palliative care by combining quantitative and qualitative evidence, providing a more comprehensive view of the topic. This allows us not only to assess the effectiveness of interventions, but also to understand the experiences and perceptions of patients and caregivers. Integrating multiple data sources and methods improves our understanding of the contexts and factors that influence the success of interventions, which can better guide clinical practice and policy formulation.

To carry out this study, an integrative review of a descriptive nature was conducted on the scientific evidence from January 2017 to June 2022, following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (Table S1) [17,18]. The review has been registered in the PROSPERO platform with the ID number CRD42023418065.

There were five databases searched during this review: PubMed, Cuiden, the Web of Science (WoS), Cochrane and LILACS (the most important international databases in nursing).

2.2. Search Strategy

To do the searches, the research question was formulated following the PIO format (population, intervention, outcomes). Those searches were carried out between October 2022 and June 2023, in order to incorporate the latest interventions.

The clinical question was which community or training interventions (I) can help improve palliative care (in terms of quality of life) (O) for patients with palliative care needs in the community or at home (P).

A community health intervention is a planned, collaborative strategy that aims to improve the health of individuals within a specific community. These interventions address health problems through active community participation, multisectoral collaboration and the implementation of programmes and activities tailored to the needs and characteristics of the local population.

The same search string was used in the different databases searched. The search string included the Boolean operator AND and the DeCS (Health Science Descriptors, for its Spanish acronym) terms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Search string used in the different databases.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were considered:

- Scientific papers published in the last 5 years, to focus on the latest evidence.

- Papers written in Spanish and English.

- Papers that include interventions applicable to patients in need of palliative care and at a community level.

- Papers directed towards both the paediatric and adult populations.

- Qualitative, descriptive and interventional studies, systematic and integrative reviews, meta-analyses and clinical cases.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

- Research papers not applicable at a community level.

2.4. Study Selection

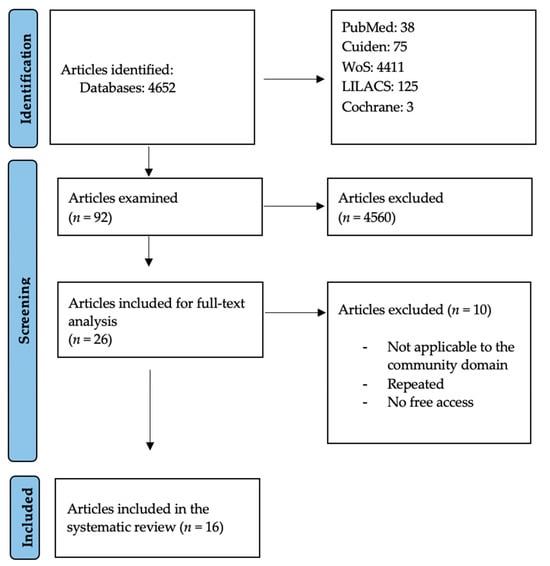

Study selection was carried out by two researchers, A.V.L. and J.M.C.T., using the inclusion and exclusion criteria mentioned above. In cases of doubt or discrepancy, a third author (J.R.S.) was consulted. The initial results of the literature search included 4652 articles from the LILACS, PubMed, Cuiden, Cochrane and WoS databases (Figure 1). After a first screening by title and abstract, 92 articles were left. After a full-text review and the quality assessment with the CASPe [19] tool, 16 articles were selected for data collection and analysis of results.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of literature search procedure (source: PRISMA) [15,16].

2.5. Studies Quality Assessment: Detection of Possible Biases

In order to assess the methodological quality of the selected documents, the CASPe [19] checklists were used, and their questions were adapted to each study design type. The CASPe checklists do not assign a numerical value to each study, but they help determine the validity and reliability of its design and analyse the strengths and weaknesses of clinical trials. None of the eligible studies were excluded from the review due to quality concerns. All included studies were assessed for quality and independently reviewed by two reviewers (AVL and JRS. Reliability between reviewers was high, and all discrepancies were discussed until an agreement was reached. As a measurement of methodological quality, it was determined that each study should have a 50% positive rating.

2.6. Results Extraction

For the data collection from the selected articles, an ad hoc table was created, containing the following information: title, authors and year of publication, study type, intervention type, sample size, results, conclusions and study quality (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the articles comprised in the unit of analysis.

2.7. Data Analysis

The data were analysed to compare outcomes between different community interventions that can improve the quality of life in patients with palliative needs at a community level.

2.8. Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. No institutional or other licensing committee’s approval was needed for guideline creation, as participants were not subjected to procedures and were not required to follow rules of behaviour.

3. Results

A total of 16 articles were selected. These included one longitudinal study, one cohort study, one cross-sectional study, five systematic reviews, five qualitative studies, two mixed-methods studies and one quasi-experiment study.

The selected studies included a total population of 11,517 palliative care patients. The studies were carried out between 2018 and 2022, in the following locations: Brazil [21,22], Spain [10], Belgium [12,23], Argentina [24], Korea [20], China [11], Portugal [25], Singapore [26], Australia [27] and France [3].

3.1. Thematic Synthesis

The unit of analysis comprises 16 articles that focus on different interventions that can be made in the community to improve the quality of life of people with palliative care needs and their families.

3.1.1. Music Therapy

In their article, Sousa, Silva & Paiva highlight the importance of music therapy, physical exercise, massage, the use of therapeutic toys and early nursing consultation for the treatment of pain, anxiety and fatigue. However, there are some negative results due to the nursing staff’s lack of training, technical skills and emotional expertise for the application of these activities in patients with palliative care needs [21]. Music therapy can naturally alleviate pain, provide relief and comfort, and improve the relationship between patients with palliative care needs and their families through the expression of emotions. It is one of the non-invasive interventions with minimum side effects that crosses cultures and binds them together [28].

3.1.2. Laughter Therapy

Interventions such as laughter therapy at home, performed by clowns, have been shown to lower anxiety and sadness levels, improving the quality of life and the domain of social activities thanks to social support. It has been noted that it is important to finance these kinds of interventions and to carry out further research to help develop these activities and raise awareness of them [19]. The use of humour as a therapy improves communication and connection among patients, their families and the professionals who face end-of-life experiences every day. It encourages the ability to escape the issues and burdens derived from the illness. Furthermore, they emphasise the importance of using humour as a means of communication and expression, which helps social interactions. There are not enough studies about this topic [29].

3.1.3. Cognitive Interventions

Cognitive–existential therapy for caregivers encourages self-care, reduces compassion fatigue and improves the caring experience of people in need of palliative care. Rational emotive therapy and logotherapy promote social skills and human strengths. The aim is to detect different everyday issues and situations and to teach how to overcome them.

In the study by Hidalgo-Andrade et al., an intervention consisting of eight sessions was conducted using Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy and Albert Ellis’ rational emotive therapy as theoretical frameworks. The intervention was developed in response to specific needs identified in a previous qualitative study on compassion fatigue and the job satisfaction of formal caregivers. These interventions improve the quality of life of caregivers, which in turn results in a better quality of care and support for people in need of palliative care [20]. The intervention has been shown to be effective in the long term in reducing compassion fatigue, making it replicable and promising. It is suggested that future studies evaluate its effectiveness in settings outside of palliative care to extend its applicability.

3.1.4. Aromatherapy

One study about aromatherapy, reflexology and massage concludes that even if these therapies are highly valued by patients, there is not enough scientific evidence to prove their efficacy. The problem might be the study’s approach, since the researchers do not reflect on any negative or dangerous aspects of these interventions [30].

3.1.5. Interdisciplinary Community-Based Teams

Interventions related to the identification of patients with palliative care needs and interdisciplinary home care by primary and secondary care teams improve cost management (programme sustainability and avoiding hospitalisations) and the care experience for providers, patients and their families [10]. These teams, made up of professionals from various disciplines, perform comprehensive assessments, coordinate care, educate patients and caregivers and provide regular follow-ups. Among the services offered are medical and nursing care, rehabilitation therapies, palliative care, nutritional support and social services. They assist with daily activities such as bathing and grooming and provide supervision to ensure patient safety.

When home and community care interventions are implemented after team building and the integration of shared medical records, and are widely disseminated and promoted, they can improve resource management and quality of life for the patient’s family, while ensuring that the patient’s wish to die at home and in the community is respected [12]. In Korea, most cancer patients expect to receive home care. Palliative care teams provided palliative care training and increased awareness of palliative care, and also demonstrated relief of pain, anxiety and depression in these patients [20]. In France, it was concluded that home-based interventions help reduce the number of hospitalisations, which increases the quality of care and patient satisfaction. Community-based interventions include external resources, such as infrastructure, and internal resources related to healthcare professionals, such as time management and the use of the home as a source of information about the patient’s condition [12].

3.1.6. Advance Care Planning

Advance care planning interventions alleviate pain, as well as the economic and psychological burden of caregivers and family members. In order to provide this kind of care, training and education are needed to avoid fear in the communication between providers and their patients and relatives. Nurses have a privileged position in this therapeutic relationship since they are the closest to the patients and they spend the most time caring for them. It is important to highlight the refusal to implement this measure due to a lack of human resources and Chinese culture and legislation [11]. It is necessary to eliminate the prohibition to ask people in need of palliative care how they wish to die; they need to be able to make autonomous decisions and talk about them with their families so that an excellent level of care is ensured while respecting their wishes. It is necessary to organize nation-wide campaigns to promote talking about death and respecting decisions [26]. There were positive aspects detected in interventions such as education on symptoms for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, advance care planning, a holistic approach to illness, breathlessness management, etc. However, studies were inconclusive and further research with enough power is needed to confirm that these people benefit with a higher quality of life [31].

3.2. Community, Volunteering, Telemedicine and Care Mapping

Educational intervention programmes implemented in a teenage population can be a great resource to raise awareness about palliative care, as well as to encourage and engage community participation in such types of care. Educating people to talk about different ethical issues could improve their quality of life and help develop more compassionate cities [23]. By determining who provides palliative care, how and where they do it and its related problems, communication, early identification of illnesses that require palliative care and education can all be improved. Palliative care provision maps can improve the lives of neighbours from a certain area who are in need of care [23]. Volunteers carry out supporting interventions in the community as a supplement to professional caregiving. They need adequate training and education since they will be on their own at the home of a person who is at the end-of-life stage or who has already done advance care planning [27].

The most significant findings regarding the types of intervention are the following: music therapy can relieve pain, provide relief and improve relationships through the expression of emotions. Laughter therapy uses humour as a means of communication and expression, which promotes social interactions. Cognitive interventions can detect problems and teach coping skills. Aromatherapy may reduce anxiety and pain, although studies are inconclusive. Interdisciplinary home care teams improve the care experience by respecting the will of patients to die at home while reducing healthcare costs. Advance care planning could reduce pain and economic and psychological burdens by avoiding the fear of communication and improving social relationships. Regarding volunteering, telemedicine, community and care maps can be a great resource for raising awareness and promoting quality palliative care, while engaging citizens to participate in the community.

4. Discussion

This integrative review confirms that implementing community-based interventions for people in need of palliative care and their families can improve their quality of life and provide relief at home throughout the illness process.

Interventions that can be implemented at a community level, such as music therapy [21,28] or laughter therapy [20,29], provided there has been previous training on their application, can encourage emotional expression and foster distraction or even relaxation, which are needed to face the suffering of having an incurable disease. The development of clown activity projects provided a significant improvement on the level of social support and social relationships in general, because smiling helps one regain one’s confidence [22].

Spiritual and cognitive interventions [24] also bring benefits to people in need of palliative care and their families. The sick patients start expressing suffering or concerns about the purpose of their existence, so these interventions seek anything that can help them find meaning in life, understand the irreversible nature of the process, express emotions, or get protection and relief. We take care not only of the body, but also of the mind. This study was an eight-session psychoeducational intervention that combined existential and cognitive therapy techniques to decrease compassion fatigue and increase compassion satisfaction in formal caregivers. Thanks to advance care planning [11,23,29], we can sense how patients prefer to die, and even where and with whom. Different scenarios can be considered throughout the process of the illness. This is the decision-making process of informed patients who have been trained and guided by their healthcare providers. Being aware of this is essential to respect the people who are at a terminal stage, and to reduce pathological grief or complicated grieving processes in their families or caregivers, by providing them with much-needed confidence towards the end of the process.

Care mapping and volunteering [23,25,27] are community-based interventions currently at their peak, and they allow us to include the community in the caring process. Terms such as patient training, population empowerment, motivation or resource mapping show that it is the people who have the power to care for their health, and that they just need the providers’ support to be able to attain it. Concepts such as compassionate cities advocate such power and stress the importance of identifying the resources available in each neighbourhood, helping improve people’s lives and sharing responsibilities.

Interdisciplinary care [3,12,13,14] and volunteer collaboration [27] enable high-quality home-based care at a lower cost for the healthcare system. The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic stressed the importance of telemedicine, like virtual support or consultation and urgent care in real time. Technology and telemedicine can transform community-based palliative care by improving access to specialized care, regardless of geographic location. They enable remote symptom monitoring, virtual consultations, and ongoing support, reducing the need for hospitalisations and in-person visits. This facilitates more personalized and timely care, improving patients’ quality of life and easing the burden on caregivers. In addition, telemedicine can optimize resource utilization and expand the reach of palliative services to underserved areas. For example, they can help diagnose skin diseases, or through videos, analyse respiration or identify possible dysphagia. There are also teaching resources available such as recordings of parents changing a tracheostomy or instructions on how to programme a feeding pump [32,33,34]. Having an interdisciplinary team that can address all aspects of care of a person who has palliative care needs is fundamental to the improvement of the experience during the illness, both for the patient and their caregivers or loved ones. Support during their life, final moments and at their deathbed is needed.

4.1. Study Limitations

We found clear limitations to interventions, such as aromatherapy or reflexology [35]. This is because there are not enough studies that prove the efficacy of these interventions in improving the quality of life or reducing pain in patients, and because of the approach taken in these studies. The heterogeneity in the types of studies included is to be highlighted.

In this integrative review, only two studies carried out in Spain were found. One dealt with the importance of developing cognitive–existential therapies as a means to reduce compassion fatigue in caregivers, while the other studied the impact of integrated palliative care programmes. All of the above makes us reflect on the types of community-based interventions that nurses currently implement in Spain and how interesting it would be to apply interventions that have already been studied in other countries.

The strength of this study is the possibility it provides of integrating these findings into a strategy (provided a previous mapping of palliative care resources and interventions is done in the community). The strategy would include clinical education, active listening and the promotion of health-related activities by primary care offices together with palliative care units, since doing so in the community has low costs. With this strategy, we could avoid issues that affect patients’ families, such as depression, anxiety or a sense of defeat. With respect to the patient, as we have already mentioned, we can improve their quality of life, help them express their emotions, avoid unnecessary hospitalisations, reduce loneliness, etc.

These interventions are not mutually exclusive, and their combination can strengthen their effects in terms of meeting the needs that arise in the community environment. For example, the combination of laughter therapy, aromatherapy and music therapy is accessible, does not incur additional costs and is easy to do in the home setting within the community.

4.2. Implications for Nursing and Health Policies

Nurses are the health professionals who make the greatest number of home visits, many of them to patients requiring palliative care. This article has identified interventions that nurses can apply in patients’ homes. There is a need for health policy makers and health managers to implement these interventions in their care programmes, especially in primary care, as they have been shown to be easy and inexpensive to implement. In fact, these interventions would reduce healthcare costs by improving the quality of life of patients and their caregivers, thereby reducing the number of visits needed and the costs they generate.

For example, for a community-based palliative care educational intervention, the target population could be selected in coordination with the local palliative care team. Taking advantage of the proximity and continuity of care of primary care nurses, schools for caregivers and patients can be organized with the aim of improving their experience of care, with organizers collecting suggestions including concerns or areas they want to work on and organizing it in a community way, accessible and adapted to the environment and people’s habits. Activities such as training in home care, stress management, etc. can be programmed.

There are currently few community projects in palliative care. We are going through a process of change in the medical model of care, where community care [29] is gaining more and more prominence, but it is not specialized in palliative care. We still have a long way to go, to eliminate taboos, to bring death and illness closer to the community and to work together so that people may die in the place they wish and with the people they wish to be with.

5. Conclusions

Community-based interventions included as part of the care of people with palliative care needs improve the quality of life for both the sick person and their caregivers or family members.

We have detected interventions that can be done in the community and at home, which reduce health costs, improve the overall experience during the illness process, and foster companionship in care (volunteer networks, education about end-of-life care, etc.).

We have also identified interventions that are easily accessible (laughter therapy, telemedicine or music therapy), simple enough to be carried out at home and that do not incur high costs. They could be of great help in communities supported by interdisciplinary palliative care teams who work with associations and organizations from the neighbourhoods together with volunteers (spiritual interventions, advance care planning, etc.).

Community-based interventions can alleviate needs that arise in people with palliative needs, accompanying and providing the best care adapted to the environment and the resources that people in that geographic area have. They can also reduce inequalities in healthcare, because patients are not affected by a geographic gap or distance and can use available community resources and the support of their primary care team together with specific interdisciplinary palliative care teams to enjoy their last moments in the place they want to be and with the people they want to be with. Due to the scarce number of articles about the topic studied, we conclude that further research is necessary to discover more types of community-based interventions and determine their influence on the domain of palliative care.

As future research, we propose studies that analyse the benefits of establishing palliative care training for adults and children in the community setting, promoting compassionate cities as a tool for empowerment in rural settings. Also, it could be interesting to analyse the effect of the implementation of workshops or seminars on palliative care in rural settings as part of university healthcare degrees in order to have professionals in the future who are well trained to meet patient needs in palliative settings and can create high-resolution primary care consultations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare12151477/s1, Table S1: PRISMA Checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V.-L., J.M.C.-T., J.R.-S., Á.L.-G., J.A.L.-A. and D.C.-P.; formal analysis, A.V.-L., J.M.C.-T., J.R.-S., Á.L.-G., J.A.L.-A. and D.C.-P.; investigation, A.V.-L., J.M.C.-T., J.R.-S., Á.L.-G., J.A.L.-A. and D.C.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.V.-L., J.M.C.-T., J.R.-S., Á.L.-G., J.A.L.-A. and D.C.-P.; writing—review and editing, A.V.-L., J.M.C.-T., J.R.-S., Á.L.-G., J.A.L.-A. and D.C.-P.; supervision, A.V.-L., J.M.C.-T., J.R.-S., Á.L.-G., J.A.L.-A. and D.C.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. No institutional or other licensing committee’s approval was needed for guideline creation, as participants were not subjected to procedures and were not required to follow rules of behaviour.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable. No new data were created or analysed in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank María Ángeles Bernal as a paediatric nurse and friend, for giving us the vision of palliative care as the highest splendour of nursing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- WHO. Palliative Care. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Blay, C.; Martori, J.C.; Limón, E.; Oller, R.; Vila, L.; Gómez-Batiste, X. Search for your 1%: Prevalence and mortality in a community cohort of people with advanced chronic disease and palliative needs. Atención Primaria 2019, 51, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boudy, C.-A.; Bouchez, T.; Caprini, D.; Pourrat, I.; Munck, S.; Barbaroux, A. Home-based palliative care management: What are the useful resources for general practitioners? a qualitative study among GPs in France. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- General Law of Health. Organic Law 14/1986 (BOE 102 del 25-4-1986). Oficial State Gazette: Madrid. 1986. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1986-10499 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Law 16/2003, of May 28, 2003, on Cohesion and Quality of the National Health System. Official State Gazette. 2003. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2003/BOE-A-2003-10715-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Daban, F.; Pasarín, M.I.; Borrell, C.; Artazcoz, L.; Pérez, A.; Fernández, A.; Porthé, V.; Díez, E. Barcelona Salut als Barris: Twelve years’ experience of tackling social health inequalities through community-based interventions. Gac. Sanit. 2021, 35, 282–288. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0213-911 (accessed on 13 February 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law 33/2011, General Law of Public Health. Official State Gazette. 2011. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2011/BOE-A-2011-15623-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Law 4/2017, of March 9, on the Rights and Guarantees of Persons in the Process of Dying. Official State Gazette. 2017. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2017/BOE-A-2017-7178-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Chang, H.-T.; Lin, M.-H.; Kuo, W.-H.; Chen, C.-K.; Chen, T.-J.; Hwang, S.-J. Willingness of primary care staff to participate in compassionate community network and palliative care and the barriers they face: A mixed methods study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e046961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larrañaga, I.; Millas, J.; Soto-Gordoa, M.; Arrospide, A.; San Vicente, R.; Irizar, M.; Lanzeta, I.; Mar, J. Impact of patient identification in a palliative care program in the Basque Country. Primary Care 2019, 51, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, B.; Liang, G.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Z.; Miao, Q. Qualitative assessment of the intention of Chinese community health workers to implement advance care planning using theory of planned behavior. BMC Palliat. Care 2021, 20, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maetens, A.; Beernaert, K.; De Schreye, R.; Faes, K.; Annemans, L.; Pardon, K.; Deliens, L.; Cohen, J. Impact of home-based palliative care support on quality and costs of end-of-life care: A population-level matched cohort study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pessalacia, J.D.R.; Silva, A.E.; Quadros Araújo, D.H.; De Lacerda, M.A.; Dos Santos, K.C. Caregivers’ experiences in palliative care and support networks. Rev. Enferm. UFPE Online 2018, 12, 2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, A.S.; Morrison, R.S. Palliative care for the seriously ill. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, D.E.; Beresford, L. Palliative care’s challenge: Facilitating transitions of care. Health Aff. 2008, 27, 1347–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.M.; Fairchild, A.; Pituskin, E.; Borgersen, P.; Hanson, J.; Fassbender, K. Improving access to palliative care through interdisciplinary telehealth: A palliative care team project. J. Palliat. Med. 2013, 16, 703–707. [Google Scholar]

- PRISMA. Prisma-statement.org. Available online: https://prisma-statement.org//PRISMAStatement/FlowDiagram.aspx (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cabello López, J.B. Critical Reading of Clinical Evidence, 1st ed.; Lectura Crítica de la Evidencia Clínica; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.O.; Kim, S.N.; Shin, S.H.; Ryu, J.S.; Baik, J.W.; Kim, J.R.; Kim, N.H. Evaluation of Outcomes of the Busan Community-based Palliative Care Project in Korea. Asian Nurs. Res. (Korean Soc. Nurs. Sci.) 2018, 12, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva e Sousa, A.D.R.; Silva, L.F.; Paiva, E.D. Nursin interventions in palliative care in Pediatric Oncology: An integrative review. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2019, 72, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, F.R.; Pinto, S.; Pessalacia, J.D.R.; Luchesi, B.M.; Silva, L.A.; Marinho, M.R. Effects of activities with clowns in patients eligible for palliative care in primary health care. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2021, 74, e20200431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderstichelen, S.; Houttekier, D.; Cohen, J.; Van Wesemael, Y.; Deliens, L.; Chambaere, K. Palliative care volunteerism across the healthcare system: A survey study. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 1233–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hidalgo-Andrade, P.; Martínez-Rodríguez, S. Development of a cognitive-existential intervention to decrease compassion fatigue in formal caregivers. Interdiscip. Rev. Psicol. Cienc. Afines 2020, 37, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins Pereira, S.; Araújo, J.; Hernández-Marrero, P. Towards a public health approach for palliative care: An action-research study focused on engaging a local community and educating teenagers. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Menon, S.; Kars, M.C.; Malhotra, C.; Campbell, A.V.; van Delden, J.J.M. Advance Care Planning in a Multicultural Family Centric Community: A Qualitative Study of Health Care Professionals’, Patients’, and Caregivers’ Perspectives. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2018, 56, 213–221.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saurman, E.; Lyle, D.; Wenham, S.; Cumming, M. Un estudio de mapeo para guiar un enfoque paliativo de la atención. Rural Remote Health 2019, 19, 4625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyashanu, M.; Ikhile, D.; Pfende, F. Exploring the efficacy of music in palliative care: A scoping review. Palliat. Support Care 2021, 19, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linge-Dahl, L.M.; Heintz, S.; Ruch, W.; Radbruch, L. Humor Assessment and Interventions in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candy, B.; Armstrong, M.; Flemming, K.; Kupeli, N.; Stone, P.; Vickerstaff, V.; Wilkinson, S. The effectiveness of aromatherapy, massage and reflexology in people with palliative care needs: A systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2020, 34, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broese, J.M.; de Heij, A.H.; Janssen, D.J.; Skora, J.A.; Kerstjens, H.A.; Chavannes, N.H.; Engels, Y.; van der Kleij, R.M. Effectiveness and implementation of palliative care interventions for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2021, 35, 486–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bruera, E.; Yennurajalingam, S. Palliative care in advanced disease: How to improve quality of life. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2012, 62, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calton, B.A.; Rabow, M.W.; Branagan, L.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Parker Oliver, D.; Bakitas, M. Top ten tips palliative care clinicians should know about telepalliative care. J. Palliat. Med. 2019, 22, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, S.; Wittenberg, E.; Knapp, C.; Yin, Z.; Breuer, C. Communication in pediatric palliative care: A review of existing literature. J. Support Oncol. 2013, 11, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ernesto, C.-M.; Rodrigo, R.-T. Salud comunitaria: Una revisión de los pilares, enfoques, instrumentos de intervención y su integración con la atención primaria. J. Negat. No Posit. Results 2021, 6, 393–410. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2529-850X2021000200011&lng=es (accessed on 13 July 2024). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).