Abstract

Digital applications have changed therapy in prosthodontics. In 2017, a systematic review reported on complete digital workflows for treatment with tooth-borne or implant-supported fixed dental prostheses (FDPs). Here, we aim to update this work and summarize the recent scientific literature reporting complete digital workflows and to deduce clinical recommendations. A systematic search of PubMed/Embase using PICO criteria was performed. English-language literature consistent with the original review published between 16 September 2016 and 31 October 2022 was considered. Of the 394 titles retrieved by the search, 42 abstracts were identified, and subsequently, 16 studies were included for data extraction. A total of 440 patients with 658 restorations were analyzed. Almost two-thirds of the studies focused on implant therapy. Time efficiency was the most often defined outcome (n = 12/75%), followed by precision (n = 11/69%) and patient satisfaction (n = 5/31%). Though the amount of clinical research on digital workflows has increased within recent years, the absolute number of published trials remains low, particularly for multi-unit restorations. Current clinical evidence supports the use of complete digital workflows in implant therapy with monolithic crowns in posterior sites. Digitally fabricated implant-supported crowns can be considered at least comparable to conventional and hybrid workflows in terms of time efficiency, production costs, precision, and patient satisfaction.

1. Background

The global trend towards digitization dominates all fields of dentistry today. Particularly in fixed prosthodontics, as a technique-oriented discipline, computerized dentistry has enabled new clinical protocols and production processes [1]. While the continuous development of computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM) techniques is the driving force in dental technology, the adoption of intraoral scanners (IOS) has significantly changed clinical procedures in recent years [2]. Together, these technologies now enable complete digital workflows for single-visit treatments for tooth-borne (tooth-supported) and implant-supported monolithic fixed dental prostheses (FDPs) [2].

Complete digital protocols consist of three main work steps: (i) the 3D acquisition of the individual patient situation directly in the mouth with IOS; (ii) digital design with dental software applications (CAD) for rapid prototyping such as milling or 3D printing (CAM) in a fully virtual environment without any physical dental models (plaster casts); and (iii) clinical delivery of the dental restoration [3]. Crucial steps are the generation, transfer, and further processing of the created IOS data (in Standard Tessellation Language [STL] format) [4]. Overall, the digital workflow is associated with mechanically high-quality monolithic restorations and reproducible fabrication in a simplified process with a reduced need for manual human interaction [5].

In the past, dental research has mostly focused on a single step within this three-step process. Typically, the focus was on in vitro analyses in terms of precision and accuracy, comparing either different IOS systems or rapid prototyping methods for fabricating the final restorations. Besides some single case reports, there was a lack of clinical studies in the dental literature, particularly randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the entire digital workflow [6].

It is important to understand the impact of the current digitalization trend on changing well-established protocols in terms of the clinical and technical feasibility of complete digital workflows, the long-term results, and the economic implications [7,8,9]. In 2017, a systematic review was the first to screen the scientific literature for evidence describing the use of complete digital workflows in fixed prosthodontics for treatment with tooth-borne or implant-supported fixed restorations. This review concluded that the level of evidence for complete digital workflows was low: only three publications investigating single-unit restorations were included, and no studies investigating multi-unit restorations were identified at that time [6].

Advances in the application of digital hardware and software in dentistry occur fast. In recent years, numerous new technologies and commercial products have been released, both for IOS systems and in the CAD/CAM domain. A non-specific PubMed search using the term “digital dentistry” yields 2070 publications for the year 2022. When limited to the year 2017 (the time of the original review), only 953 of the techniques are identified, less than half. Based on this massive increase in such a short period of time, it is of interest to know if the proportion of qualitative clinical trials in fixed prosthodontics has also increased in line with this trend. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to update the review originally published in 2017, to present current data describing the latest developments in digitally enhanced fixed prosthodontics, and to derive clinical recommendations for routine use.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

This systematic review is an updated version of a review published in 2017 [6]. The search strategy, based on the PICO criteria, as well as the inclusion criteria are consistent with the previous publication and have been adapted for the new timeframe. The PICO question was formulated as follows [6]: “Is a complete digital workflow with intraoral optical scanning (IOS) plus virtual design plus monolithic restoration for patients receiving prosthodontic treatments with (A) tooth-borne or (B) implant-supported fixed restorations comparable to conventional or mixed analog-digital workflows with conventional impression and/or lost-wax technique and/or framework and veneering in terms of feasibility in general or survival/success-analysis including complication assessment with a minimum follow-up of one year or economics or esthetics or patient-centered factors?” [6].

A systematic electronic search was performed using PubMed, Medline, and Embase for English-language publications. Literature consistent with the original review criteria published between 16 September 2016 and 31 October 2022 was considered. In addition, grey literature, such as Google Scholar, was screened. The search syntax was categorized into population, intervention, comparison, and outcome (PICO). Each category was assembled from a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH Terms) as well as free-text words in simple or multiple conjunctions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of the electronic search strategy according to PICO criteria.

Finally, a manual search in the dental literature was also conducted. The following journals were considered: Clinical Implant Dentistry & Related Research, Clinical Oral Implants Research, European Journal of Oral Implantology, Implant Dentistry, International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants, Journal of Clinical Periodontology, Journal of Computerized Dentistry, Journal of Dental Research, Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, Journal of Oral Implantology, Journal of Periodontal & Implant Science, Journal of Periodontology, Journal of Prosthodontics, International Journal of Prosthodontics, Prosthetic Dentistry, and Prosthodontic Research. An additional search of the bibliographies of all full-text articles, selected from the electronic search, was performed.

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) [10].

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

This systematic review focused on RCTs as the highest level of clinical evidence, particularly those describing complete digital workflows in fixed prosthodontics that analyzed at least one of the following parameters: economics in terms of time and/or cost analyses, esthetics, patient-centered outcomes with or without follow-up, as well as survival and success rate analyses including assessments of complications of at least 1 year under function. The following inclusion criteria were defined [6]:

- Clinical trials, limited to RCTs with at least 10 patients;

- Treatment concepts with FDPs, either tooth-borne or implant-supported for single- or multi-unit restorations;

- Processing of a complete digital workflow (without physical models); and

- Reporting of information on the used clinical work steps and technical production.

2.3. Selection of Studies

Title and abstract screening were performed by two independent researchers (S.A.B. and T.J.), who considered the defined inclusion criteria. If the provided information was not sufficient, full texts were retrieved and evaluated by both reviewers. Several publications reported on the same patient population; these publications that summarized different outcomes were merged. Selected articles were subjected to further analyses. Throughout this complete process, disagreements were resolved through discussion.

2.4. Data Extraction

The following information were extracted from the included publications: author, year of publication, description of the specific study design, number of patients treated and examined, type of fixed restorations (including the number of abutment teeth and/or dental implants), clinical treatment concept, methodological approach for laboratory processing, description of the material properties, as well as defined primary (and secondary) outcomes.

Finally, all included studies were subdivided into four groups based on the type of prosthetic abutments and the number of units: A1. tooth-borne single crowns; A2. tooth-borne multi-unit FDPs; B1. implant-supported single crowns; and B2. implant-supported multi-unit FDPs. The information extracted from the articles was tabulated, and if possible, a meta-analysis was to be conducted.

3. Results

3.1. Included Studies

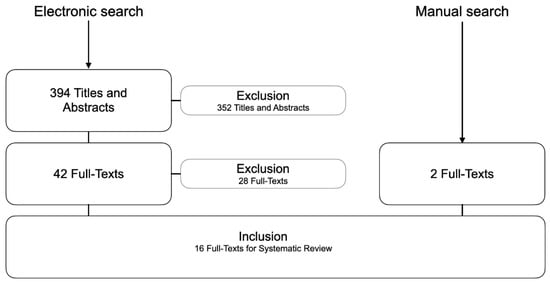

The systematic search was completed on October 31, 2022, and results are current as of this date. Of the 394 titles retrieved by the electronic search, 42 potentially relevant abstracts were identified; however, 28 of these were excluded from the final analysis. In addition, two studies were found through manual search, resulting in a total of 16 studies for data extraction (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow-chart showing the electronic and manual search results.

The reasons for exclusion were (n = 28):

- No data on complete digital workflows (n = 5)

- Not an RCT (n = 17)

- Workflow did not investigate final prosthetic restorations (n = 6)

3.2. Descriptive Analysis

The 16 identified RCTs reported on a total of 440 patients, with 236 tooth-borne restorations and 422 implant-supported restorations. Only one of the 16 RCTs included follow-up examinations. General data for study design, type of fixed restoration, number of subjects, and defined outcomes are summarized in Table 2. Based on the prosthetic design, included studies were divided into four groups: (A1) six publications for tooth-borne single-unit restorations [11,12,13,14,15,16,17]; (A2) no publication for tooth-borne multi-unit restorations; (B1) eight publications for implant-supported single-unit restorations [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]; and (B2) two publications for implant-supported multi-unit restorations [26,27,28,29].

Table 2.

General data of the included trials, including study design, type of fixed restoration, number of investigated subjects, and defined outcome(s).

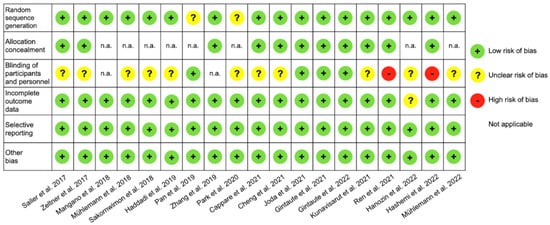

Due to the heterogeneity of the included RCTs with different study designs and outcomes, a direct comparison among the identified publications was not feasible, and consequently, a meta-analysis could not be performed. Thus, the review of the full texts followed a descriptive analysis. Detailed information of each study, categorized in A1-B1-B2, is shown in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5. Figure 2 displays the risk of bias for the included studies. No additional analyses were performed.

Table 3.

Detailed study information according to the type of restoration A1 (tooth-borne single-units).

Table 4.

Detailed study information according to the type of restoration B1 (implant supported single-units).

Table 5.

Detailed study information according to the type of restoration B2 (implant supported multi units).

Figure 2.

Presentation of risk of bias assessments for included studies according to the Cochrane collaboration’s tool.

3.3. Group A1—Tooth-Borne Single-Unit Restorations (Table 3)

Six studies compared digital to conventional workflows for tooth-borne single crowns, with a total of 236 prosthetic units. Regarding the precision of marginal fit of the FDPs, three studies found no statistically significant differences of the fabricated crowns between workflows [14,16,17]. One RCT documented a trend towards better marginal fit for the conventional workflow [13]. Another RCT found better marginal and internal adaption for crowns fabricated with digital workflows, but the clinical evaluation showed similar marginal adaptation [12]. Occlusal contacts were found to be better for digitally produced crowns, while no differences were found for marginal fit, proximal contact, and crown morphology [11].

Four studies also investigated time efficiency, with two studies reporting no statistically significant differences in total clinical treatment times [13,15], and one study showing a shorter impression time for IOS compared with a conventional workflow [14]. The other RCT investigated a complete digital workflow, different hybrid workflows with a physical cast, and a conventional workflow as a control [15]. Laboratory fabrication time was significantly shorter for the conventional cast compared to all CAD/CAM casts because the digital workflow included delivery of the CAD/CAM cast from the manufacturer to the dental laboratory. Delivery of the crowns was significantly faster for the fully digital workflow, followed by the conventional workflow.

3.4. Group B1—Implant-Supported Single-Unit Restorations (Table 4)

This group comprised eight studies, including 302 patients. A total of 342 implant-supported single crowns were examined. The most frequently considered topic was time efficiency (n = 6), followed by precision (n = 5), patient satisfaction (n = 4), esthetics (n = 4), marginal-bone loss (n = 2), and cost efficiency (n = 1). For economic analyses, all studies that examined time efficiency found significantly higher time savings for digital workflows (n = 6/6 studies), and costs were also significantly lower for the complete digital approach (n = 1/1 study). Patient satisfaction was rated significantly better for digital solutions in most publications (n = 3/4 studies). For the three other parameters (precision, esthetic outcome, and marginal bone loss), no significant differences between the workflows were reported.

3.5. Group B2—Implant-Supported Multi-Unit Restorations (Table 5)

Two studies investigated implant-supported multi-unit restorations with a total of 30 patients. Eighty implant-supported three-unit FDPs were fabricated either with digital or conventional workflows. Both studies examined time efficiency. Hashemi et al. stated significant less mean laboratory time and a shorter total fabrication time for the digital workflow [28]. Joda et al. [29] investigated time efficiency of two different digital and one conventional workflow. Significant differences in time efficiency for pairwise comparisons of the total work time were observed. The proprietary digital workflow 3Shape (IOS: TRIOS 3 Pod) was shown to be more time-efficient than the conventional workflow, while the proprietary digital workflow Dental Wings (IOS: Virtuo Vivo) required more time. The cost analysis was favored the digital workflow, with significantly lower production costs for completely digital fabricated FDPs [29]. Based on the same study population, patient-centered outcomes and clinical performance were also investigated [27]. Patient satisfaction with the final monolithic ZrO2 FDPs, as assessed in a double-blind testing, revealed no significant difference between the different workflows, but significantly lower overall ratings were reported by the dental professional than by patients [27]. Finally, the mean total chairside adjustment time, as the sum of interproximal, pontic, and occlusal corrections, was not significantly different among all three workflows [26].

4. Discussion

This systematic review aimed to summarize recent data from RCTs on conventional versus complete digital workflows for fabrication of FDPs. Overall, data from 658 FDPs from 16 RCTs were summarized. The review found ambiguous results for clinical parameters in tooth-borne single-unit restorations, while for implant-supported single- and multi-unit restorations, significantly shorter fabrication time at lower costs was demonstrated for digital compared to conventional workflows.

The systematic search strategy and inclusion criteria used in the present review were identical to those used in the previous review [6], only the time frame was adjusted. In general, RCTs provide the best clinical evidence for generating a systematic review, and only this study type was included. Consequently, the number of included publications was smaller than if all study types had been considered. Compared with the previous review that covered publications up to September 2016 and identified three RCTs, the present systematic review covering the last 6 years identified five times as many RCTs, including two studies of multi-unit restorations. Nevertheless, this still represents relatively few studies compared with the hundreds of publications that report FDP treatment using purely conventional protocols. This suggests that the long-predicted hype for digitization in the MedTech industry has yet to be realized.

Interestingly, the number of studies in the subgroups A1-B1-B2 showed a heterogeneous distribution, and no RCT was identified that investigated a complete digital workflow for tooth-borne multi-unit restorations. Most included RCTs (10/16; 63%) investigated implant-supported restorations. Possible explanations for this include a general trend towards more implant-driven treatment concepts, the fact that complete digital workflows are simply predestined for monolithic restorations on implants, or that the funding of clinical trials by industrial sponsors favors implant concepts.

Most of the identified RCTs (12/16; 75%) focused on time efficiency as an economic key performance indicator [11,13,14,15,18,21,22,23,24,25,28,29]. Eleven studies (69%) investigated the precision of the FDPs [11,12,13,14,16,17,19,22,23,24,25] and five studies (32%) analyzed patient satisfaction [16,18,20,21,27]. This shows that patient-centered parameters are becoming increasingly important, in addition to the classic clinical parameters in fixed prosthodontics, such as analyses of marginal integrity and occlusion in the overall context of precision [30].

From an economic point of view, complete digital workflows could demonstrate a clear advantage over conventional procedures. This was regardless of whether the restorations were tooth-borne or implant-supported, and regardless of the size of the restorations, as single crowns or multi-units [11,13,14,15,18,21,22,23,24,25,28,29]. In terms of precision, both workflows seemed to offer similar performance, with a possible slight advantage for well-established conventional protocols over digital workflows for treatment with tooth-borne restorations [11,12,13,14,16,17,19,22,23,24,25]. Finally, the patients either did not notice any differences between digitally or conventionally produced FDPs or they rated the restorations from the digital workflows better [16,18,20,21,27].

The correct application of a workflow (digital or conventional) to an appropriate indication is crucial for the success of the overall prosthetic therapy and for a satisfied patient [31]. For digital processing, a teamwork approach is particularly important—this equally includes the clinician, the dental assistants, and the technician [32]. The complete digital workflow has the potential to become a game-changer in (fixed) prosthodontics [33].

Nevertheless, the conventional workflow remains the current gold standard. In recent years, individual components in the workflow have increasingly become digitized for both tooth-borne and implant-supported restorations. This digital change began in dental technology with the introduction of CAD/CAM technology. As a consequence, the technical-dental protocol has been transformed to a hybrid analog-digital workflow. For the indication of single crowns, especially on implants in the posterior region, there seems to be a strong trend in favor of complete digital workflows with monolithic restorations and pre-fabricated titanium base abutments [34]. Subsequently, IOS ideally has completed the clinical gap [35]. The continuous development of digital scanning techniques has enabled quick, safe, and patient-friendly 3D capturing of the clinical situation [36,37]. Use of IOS is particularly beneficial in implant therapy because it is not necessary to optically record an individual preparation margin on the tooth, but only a standardized supra-mucosal localized scanbody. For single-unit restorations, the digital bite registration is much easier and more reproducible than for multi-units [38]. Finally, economic factors offering high-level quality restoration with reduced treatment time and lower production costs are the biggest driver [39,40].

5. Conclusions

Based on the findings of this systematic review, it can be concluded that the amount of qualitative clinical research investigating complete digital workflows has increased within the last 6 years. However, the absolute number of RCTs, in particular those investigating treatment with multi-unit restorations, is still low. Good quality clinical evidence exists supporting the use of complete digital workflows in implant therapy with monolithic crowns in posterior sites. Digitally fabricated implant-supported single units can be considered at least comparable to conventional and hybrid workflows in terms of time efficiency, production costs, precision, and patient satisfaction.

Future clinical research based on RCTs is imperative to gain clarity on the clinical performance of digital workflows. The difficulty is the rapid digital evolution, so that the devices and tools from the clinical trials are already “obsolete” after 1 to 2 years (when the data are published). It is therefore particularly important that the versions of hardware and software used are always specified.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.J.; methodology, T.J. and S.A.B.; validation, T.J., N.U.Z. and S.A.B.; formal analysis, S.A.B. and T.J.; investigation, T.J. and S.A.B.; resources, T.J.; data curation, T.J. and S.A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.B. and T.J.; writing—review and editing, N.U.Z.; visualization, S.A.B.; supervision, T.J.; project administration, T.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are presented in this manuscript. No additional data source is available.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank James Ashman for English proofreading of the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alauddin, M.S.; Baharuddin, A.S.; Mohd Ghazali, M.I. The Modern and Digital Transformation of Oral Health Care: A Mini Review. Healthcare 2021, 9, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joda, T.; Yeung, A.W.K.; Hung, K.; Zitzmann, N.U.; Bornstein, M.M. Disruptive Innovation in Dentistry: What It Is and What Could Be Next. J. Dent. Res. 2021, 100, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Noort, R. The future of dental devices is digital. Dent. Mater. 2012, 28, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morsy, N.; El Kateb, M. Accuracy of intraoral scanners for static virtual articulation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of multiple outcomes. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joda, T.; Brägger, U. Digital vs. conventional implant prosthetic workflows: A cost/time analysis. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2015, 26, 1430–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joda, T.; Zarone, F.; Ferrari, M. The complete digital workflow in fixed prosthodontics: A systematic review. BMC Oral Health 2017, 17, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernauer, S.A.; Zitzmann, N.U.; Joda, T. The Use and Performance of Artificial Intelligence in Prosthodontics: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 6628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Abbasi, M.S.; Zuberi, F.; Qamar, W.; Halim, M.S.B.; Maqsood, A.; Alam, M.K. Artificial Intelligence Techniques: Analysis, Application, and Outcome in Dentistry-A Systematic Review. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 9751564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla-León, M.; Gómez-Polo, M.; Vyas, S.; Barmak, B.A.; Gallucci, G.O.; Att, W.; Özcan, M.; Krishnamurthy, V.R. Artificial intelligence models for tooth-supported fixed and removable prosthodontics: A systematic review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2023, 129, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.W.; Ye, S.Y.; Chien, C.H.; Chen, C.J.; Papaspyridakos, P.; Ko, C.C. Randomized clinical trial of a conventional and a digital workflow for the fabrication of interim crowns: An evaluation of treatment efficiency, fit, and the effect of clinician experience. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 125, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddadi, Y.; Bahrami, G.; Isidor, F. Accuracy of crowns based on digital intraoral scanning compared to conventional impression-a split-mouth randomised clinical study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 23, 4043–4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlemann, S.; Benic, G.I.; Fehmer, V.; Hämmerle, C.H.F.; Sailer, I. Clinical quality and efficiency of monolithic glass ceramic crowns in the posterior area: Digital compared with conventional workflows. Int. J. Comput. Dent. 2018, 21, 215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.S.; Lim, Y.J.; Kim, B.; Kim, M.J.; Kwon, H.B. Clinical Evaluation of Time Efficiency and Fit Accuracy of Lithium Disilicate Single Crowns between Conventional and Digital Impression. Materials 2020, 13, 5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, I.; Benic, G.I.; Fehmer, V.; Hämmerle, C.H.F.; Mühlemann, S. Randomized controlled within-subject evaluation of digital and conventional workflows for the fabrication of lithium disilicate single crowns. Part II: CAD-CAM versus conventional laboratory procedures. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2017, 118, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakornwimon, N.; Leevailoj, C. Clinical marginal fit of zirconia crowns and patients’ preferences for impression techniques using intraoral digital scanner versus polyvinyl siloxane material. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2017, 118, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeltner, M.; Sailer, I.; Mühlemann, S.; Özcan, M.; Hämmerle, C.H.; Benic, G.I. Randomized controlled within-subject evaluation of digital and conventional workflows for the fabrication of lithium disilicate single crowns. Part III: Marginal and internal fit. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2017, 117, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capparé, P.; Ferrini, F.; Ruscica, C.; Pantaleo, G.; Tetè, G.; Gherlone, E.F. Digital versus Traditional Workflow for Immediate Loading in Single-Implant Restoration: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Biology 2021, 10, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanozin, B.; Li Manni, L.; Lecloux, G.; Bacevic, M.; Lambert, F. Digital vs. conventional workflow for one-abutment one-time immediate restoration in the esthetic zone: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2022, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunavisarut, C.; Jarangkul, W.; Pornprasertsuk-Damrongsri, S.; Joda, T. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) comparing digital and conventional workflows for treatment with posterior single-unit implant restorations: A randomized controlled trial. J. Dent. 2022, 117, 103875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangano, F.; Veronesi, G. Digital versus Analog Procedures for the Prosthetic Restoration of Single Implants: A Randomized Controlled Trial with 1 Year of Follow-Up. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 5325032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mühlemann, S.; Lamperti, S.T.; Stucki, L.; Hämmerle, C.H.F.; Thoma, D.S. Time efficiency and efficacy of a centralized computer-aided-design/computer-aided-manufacturing workflow for implant crown fabrication: A prospective controlled clinical study. J. Dent. 2022, 127, 104332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, S.; Guo, D.; Zhou, Y.; Jung, R.E.; Hämmerle, C.H.F.; Mühlemann, S. Time efficiency and quality of outcomes in a model-free digital workflow using digital impression immediately after implant placement: A double-blind self-controlled clinical trial. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2019, 30, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, S.; Jiang, X.; Lin, Y.; Di, P. Crown Accuracy and Time Efficiency of Cement-Retained Implant-Supported Restorations in a Complete Digital Workflow: A Randomized Control Trial. J. Prosthodont. 2022, 31, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tian, J.; Wei, D.; Di, P.; Lin, Y. Quantitative clinical adjustment analysis of posterior single implant crown in a chairside digital workflow: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2019, 30, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gintaute, A.; Weber, K.; Zitzmann, N.U.; Brägger, U.; Ferrari, M.; Joda, T. A Double-Blind Crossover RCT Analyzing Technical and Clinical Performance of Monolithic ZrO2 Implant Fixed Dental Prostheses (iFDP) in Three Different Digital Workflows. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gintaute, A.; Zitzmann, N.U.; Brägger, U.; Weber, K.; Joda, T. Patient-reported outcome measures compared to professional dental assessments of monolithic ZrO2 implant fixed dental prostheses in complete digital workflows: A double-blind crossover randomized controlled trial. J. Prosthodont. 2023, 32, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, A.M.; Hashemi, H.M.; Siadat, H.; Shamshiri, A.; Afrashtehfar, K.I.; Alikhasi, M. Fully Digital versus Conventional Workflows for Fabricating Posterior Three-Unit Implant-Supported Reconstructions: A Prospective Crossover Clinical Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joda, T.; Gintaute, A.; Brägger, U.; Ferrari, M.; Weber, K.; Zitzmann, N.U. Time-efficiency and cost-analysis comparing three digital workflows for treatment with monolithic zirconia implant fixed dental prostheses: A double-blinded RCT. J. Dent. 2021, 113, 103779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feine, J.; Abou-Ayash, S.; Al Mardini, M.; de Santana, R.B.; Bjelke-Holtermann, T.; Bornstein, M.M.; Braegger, U.; Cao, O.; Cordaro, L.; Eycken, D.; et al. Group 3 ITI Consensus Report: Patient-reported outcome measures associated with implant dentistry. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2018, 29 (Suppl. 16), 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapos, T.; Evans, C. CAD/CAM technology for implant abutments, crowns, and superstructures. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2014, 29 (Suppl. 2014), 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zande, M.M.; Gorter, R.C.; Bruers, J.J.M.; Aartman, I.H.A.; Wismeijer, D. Dentists’ opinions on using digital technologies in dental practice. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2018, 46, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joda, T.; Ferrari, M.; Gallucci, G.O.; Wittneben, J.G.; Brägger, U. Digital technology in fixed implant prosthodontics. Periodontol. 2000 2017, 73, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thobity, A.M. Titanium Base Abutments in Implant Prosthodontics: A Literature Review. Eur. J. Dent. 2022, 16, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, R.; Galli, M.; Chen, Z.; Mendonca, G.; Meirelles, L.; Wang, H.L.; Chan, H.L. Intraoral scanning reduces procedure time and improves patient comfort in fixed prosthodontics and implant dentistry: A systematic review. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 6517–6531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihara, H.; Hatakeyama, W.; Komine, F.; Takafuji, K.; Takahashi, T.; Yokota, J.; Oriso, K.; Kondo, H. Accuracy and practicality of intraoral scanner in dentistry: A literature review. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2020, 64, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghani, M.T.; Shayegh, S.S.; Johnston, W.M.; Shidfar, S.; Hakimaneh, S.M.R. In vitro evaluation of the accuracy and precision of intraoral and extraoral complete-arch scans. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 126, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gintaute, A.; Keeling, A.J.; Osnes, C.A.; Zitzmann, N.U.; Ferrari, M.; Joda, T. Precision of maxillo-mandibular registration with intraoral scanners in vitro. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2020, 64, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, D.; Gallucci, G.; Lin, W.S.; Pjetursson, B.; Polido, W.; Roehling, S.; Sailer, I.; Aghaloo, T.; Albera, H.; Bohner, L.; et al. Group 2 ITI Consensus Report: Prosthodontics and implant dentistry. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2018, 29 (Suppl. 16), 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, I.; Mühlemann, S.; Kohal, R.J.; Spies, B.C.; Pjetursson, B.E.; Lang, N.P.; Gotfredsen, K.L.; Ellingsen, J.E.; Francisco, H.; Özcan, M.; et al. Reconstructive aspects: Summary and consensus statements of group 3. The 5th EAO Consensus Conference 2018. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2018, 29 (Suppl. 18), 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).