Abstract

Depression in the elderly is an important health factor that requires intervention in the form of social support resources. The purpose of this study was to conduct a systematic review, while synthesizing available evidence on what kind of social support, such as social participation and social connection/network, is effective for depression in the elderly. We performed a quality assessment of the included studies using the revised Risk of Bias for Non-randomized Studies tool and a meta-analysis of studies published up to 14 May 2021. Of the 3449 studies, 52 were relevant to this study. The various types of social resource applications reported in these were classified into three types: social support, social participation, and social connection/network. The social support group had significantly lower depression compared to the control group (0.72 [0.65, 0.81], p < 0.00001, I2 = 92%). There was a significant decrease in depression in the social participation group compared to the control group (0.67 [0.56, 0.80], p < 0.00001, I2 = 93%) (2.77 [1.30, 5.91], p = 0.008, I2 = 97%) (0.67 [0.56, 0.80], p < 0.00001, I2 = 93%). Finally, the social connection/network group showed decreased depression compared to the control group (2.40 [1.89, 3.05], p < 0.00001, I2 = 24%) (0.83 [0.76, 0.90], p < 0.00001, I2 = 94%). The results of this systematic review confirmed the effects of various social support interventions in reducing depression among the elderly living in the community.

1. Introduction

The pathophysiological model of human health and disease has succeeded to some extent in identifying its causes and consequences through continuous research spanning decades. However, studies on the socio-psychological impacts on human health and disease have received relatively less attention [1]. Nevertheless, the social impact on health, especially the effect of social relations, has been reported through recent studies [2,3]. More specifically, the influence of social relationships is related to the number of human relations and their quality and effects in terms of social connections [1,4]. We need to pay attention to this social connection, especially in the case of the elderly, as it can be seen that the quantity and quality of social connections directly affect the health of the elderly [1,5,6]. For example, social isolation or loneliness in the elderly was found to be associated with a 50% increased risk of developing dementia [7], 30% increased risk of coronary artery disease or stroke [8], and 26% increase in mortality rates [9]. Although there are differences by country, 16.4% of the elderly living with their spouses and 21.7% of the elderly living with their adult children experienced depression, while 30.2% of the elderly living alone experienced depression [10]. Nurses, as health care professionals, need to identify the effects of social connections on diseases among the elderly and pay attention to depression in the elderly. In particular, among the suicide risk factors in the elderly, depression is an important factor that can be mediated and has been the subject of several suicide prevention studies [11]. However, late-life depression is not easy to detect and tends to be poorly treated due to the characteristics of masked depression and senile comorbidities [5,11]. Mental health deterioration, such as depression in old age, is related to the overall risk of life, and the urgency of intervention is emphasized [12]. As one of these interventions, research on social support and depression, including social relations, is being conducted. In a study on the relationship between social participation and depression risk among 4751 local residents over 60 years old, it was reported that the risk of depression symptoms in elderly people participating in social activities, volunteering, and donation decreased [13]. In a community-based random sampling study of 959 elderly people, in addition to other known causes, low social support was identified as the cause of depression. Appropriate social support has been reported to be important in alleviating pain caused by the loss of the elderly [14]. Another study identified the effect of social network composition on depression using panel data collected between 2005 and 2016 and explored how different social layers influence each other. A study has shown that community participation has a consistent advantage in reducing depression. In contrast, intimate partnerships have been reported to increase sensitivity to depression among the elderly by exposure to serious consequences of partner loss [6]. According to observational data of 6772 individuals from China’s health and retirement end study, elderly people in rural areas experience more severe depression than elderly people in urban areas, so an approach considering residential areas is needed rather than collective application of social support [15]. These studies emphasize that local and individual resources should be considered simultaneously and comprehensively to understand depression in old age [12]. Despite the growing discussion of social resources as non-material resources for depression in old age, another intervention study reported that social interactions among the elderly improved, but depressive symptoms did not decrease [11]. A systematic review reported in 2019 confirmed that appropriate and good social support reduces depression in the elderly [5] and reported that, when solving depression in an Asian context, it is necessary to integrate the designed programs and interventions of family institutions.

Based on these findings, a more robust systematic review is needed to summarize and synthesize evidence on the relationship between depression and social support and the progress of mental health problems related to depression in the elderly, and to confirm useful evidence for how, and in what context, the elderly can affect mental health recovery. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to conduct a systematic review of existing studies on depression in the elderly in the community, while synthesizing available evidence on what kind of social support, such as social participation and social connection/network, is most effective.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Systems for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. This study was conducted to investigate the risk factors of community-dwelling elderly people with depression. We searched relevant articles on 14 May 2021, using four databases: Ovid-Medline, Ovid-Embase, PsycINFO, and CINAHL. The search was performed using the terms that included Medical Subject Headings (MeSH). Keywords were as follows (aged OR older adults OR older persons OR old OR elderly) AND (independent living OR community dwelling OR community) AND (mental health OR depression OR emotional depression OR mood disorder OR affective disorder) AND (social support OR social network OR social relations OR tangible support OR social support network scale OR emotional support OR social support network) and combinations of these terms.

2.2. Study Selection

To rule out irrelevant studies, two reviewers independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of the articles, and a professional review was conducted of the relevant articles. The literature included in this systematic review was selected based on the following criteria: (1) English or Korean papers; (2) participants aged over 60 years; (3) community-dwelling elderly persons and not living in institutions; (4) participants with depression; (5) patients had social support; and (6) reports on predictive factors. The results of interest were predefined before conducting the review. Review articles, abstracts, conference posters, unpublished gray literature, protocols, not written in English or Korean, animal studies, and duplicate studies were excluded. Two authors checked reliability using Cohen’s kappa coefficient.

2.3. Data Extraction

Using pre-agreed data inclusion criteria, the two investigators independently extracted the data for this review. Disagreements were discussed among the reviewers until a consensus was reached. The following data were extracted from each article: author, year of publication, study design, country where study was conducted (city), object country, sample size, age, location, gender, social support measure, social support explanation, and depression measurement.

Social support is defined as the exchange of resources between at least two individuals, and one individual perceives it as promoting the welfare of the recipient [16]. High social support decreases depression. To measure social support, selected studies used the Oslo-3 Social Support Scale, using geriatric depression scale (GDS-15) [17,18] the Social Support Scale, using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) [19] and the Chinese version of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support [20]. In addition, the Positive Perceived Social Support [21] the Medical Outcome Study Social Support Survey [22] the Social Support Rating Scale [23] and the Social Support Index, which comprises both receiving and providing social support [24] were used to measure social support. Antonucci et al. [25] and Kim and Park [26] checked family and friend support, and Mechakra-Tahiri et al. [27] reported functional relationships, including social support and the presence of conflict.

Social participation is defined as the participation of individuals in social activities that allow interaction with others in the community [28]. One of the two measuring instruments indicates that high social participation decreases depression. Bai et al. [29] measured social participation using the framework of the World Bank’s Social Capital Assessment Tool, and Lee et al. [30] reported the number of social participations. Other instruments show that if there is a lot of social participation, the depression decreases [27,31,32]. Social networks are concepts related to the formal structure of social relations such as size, composition, frequency of contact, and boundaries [33]. Some social networks decrease depression, using the Lubben social network scale [34,35,36] and the framework of the World Bank’s Social Capital Assessment Tool [29]. Others decrease depression scores using the Revised Lubben Social Network Scale [37,38,39], the Chinese version of the Intergenerational Relationship Scale [20], the Social Support Scale [40], the version of portions of the social networks [25], network structure and social network function [19], network size and social interaction [30,41,42], and number of visitors per week [43].

2.4. Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

We performed a quality assessment of the included studies using the revised Risk of Bias for Non-randomized Studies (RoBANS) tool. There were eight domains of the tool, including the possibility of target group comparisons, target group selection, confounders, exposure measurement, blinding of assessors, outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, and selective outcome reporting. Each domain was evaluated as “low”, “high”, or “unclear”. The outcome of the quality assessment was examined and agreed upon by the two reviewers.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

We conducted a meta-analysis using the Review Manager 5.4 (RevMan) program for the items that could be synthesized among the results of 52 included studies. The estimated effect, measured as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals, was extracted. Between the studies, I2 statistics were used to evaluate statistical heterogeneity, and a fixed-effects model was used to analyze the data. We used a random effects model when heterogeneity was absent.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

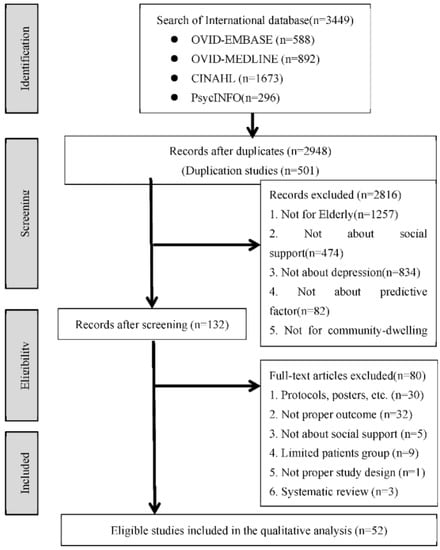

After full-test reviews, 3449 studies were searched from the database. After excluding duplicates, 2948 studies remained. A full-text review revealed that 52 documents were relevant to this study. Figure 1 illustrates a flowchart of the study selection process. Reliability was checked by two reviewers using Cohen’s kappa coefficient (k = 0.85).

Figure 1.

Flow chart.

3.2. Study Characteristics

Table 1 represents the characteristics of the 52 included studies. The search was carried out on 14 May 2021. Studies published between 1997, when the search engine started, and 2021 were considered. The selected studies included 42 cross-sectional and 10 longitudinal studies. There were 37 studies from Asia, 11 from North America, two from Africa, one from Australia, and one from Europe. Specific items for each study were research design, sample size, age, gender of participants, depression and social support measurement tools, and other related variables. Supplementary Table S1 presents the characteristics of the subjects presented in each study, and Supplementary Table S2 presents various depression intervention methods, which are the main interests of this study, classified into social support, social participation, and social connection/network.

Table 1.

The characteristics of the selected studies [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42].

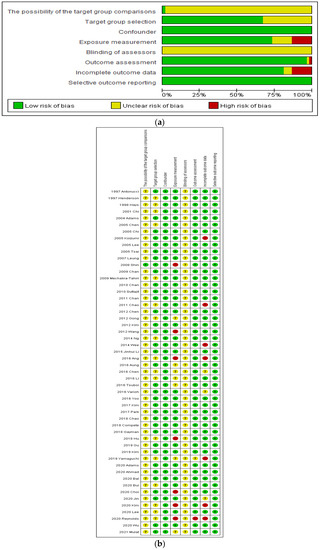

3.3. Risk of Bias within Studies

The 15 selected studies were assessed using the revised (RoBANS) tool (Figure 2). The risk of possibility of target group comparisons and target group selection were low in 35 of the 52 studies. The risk of confounding and selective outcome reporting was low for all studies. The risk of exposure measurement was low in 39 studies. The risk of blinding of assessors was unclear. The risk of outcome assessment was low in 50 studies. The risk of incomplete outcome data was low in 42 studies.

Figure 2.

Quality assessment (a) Risk of bias graph; (b) Risk of bias summary.

3.4. Meta-Analysis of Selected Studies

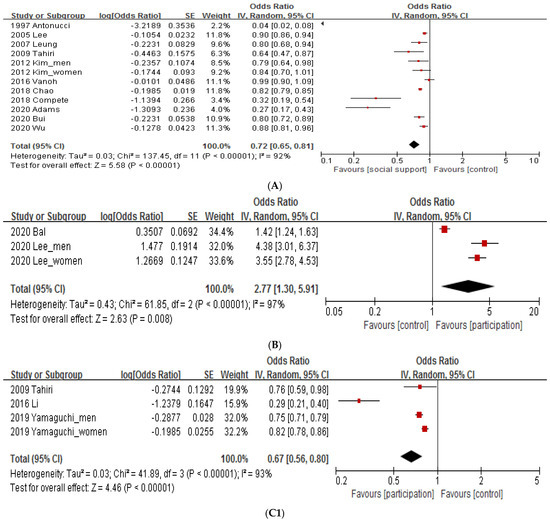

3.4.1. Social Support

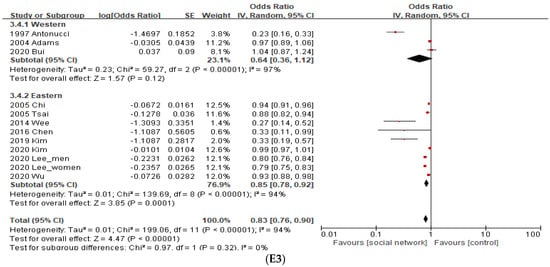

The social support group showed significantly decreased depression compared to the control group (0.72 [0.65, 0.81], p < 0.00001, I2 = 92%) (Figure 3A). Heterogeneity between studies was confirmed, and an additional subgroup analysis was performed. Subgroup analysis of social support by research type revealed that depression was significantly reduced in longitudinal studies (0.80 [0.72, 0.89], p < 0.0001) as well as in cross-sectional studies (0.71 [063, 0.80], p < 0.00001, I2 = 93%). Subgroup analysis was performed, but the heterogeneity was not reduced. In the subgroup analysis of social support of articles published by continents, social support significantly decreased depression compared to the control group in the western (0.45 [0.34, 0.61], p < 0.00001, I2 = 95%) and eastern continents (0.88 [0.83, 0.95], p = 0.0004, I2 = 54%). The heterogeneity value in eastern countries decreased, and depression decreased as social support increased in both groups.

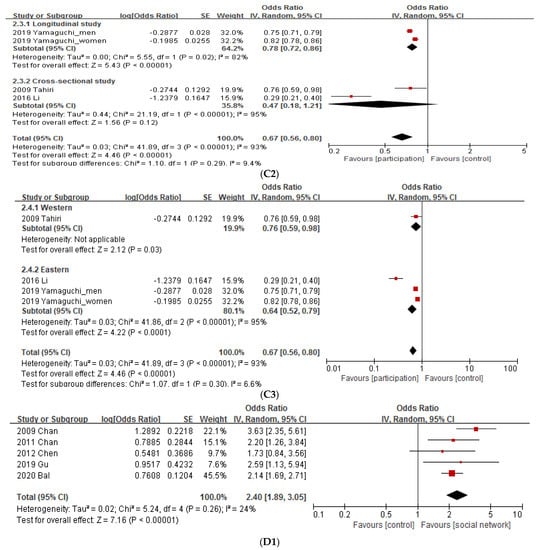

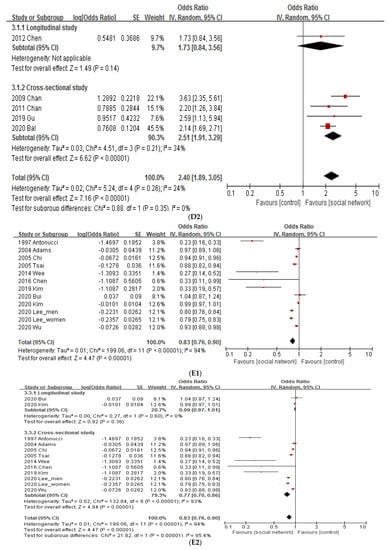

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis. (A). Social support. (B) Social participation. (C1) Social participation. (C2). Subgroup analysis of social participation by study design. (C3). Subgroup analysis of social participation by published continents. (D1). Social network. (D2). Subgroup analysis of social network by study design. (E1). Social network. (E2). Subgroup analysis of social network by study design. (E3). Subgroup analysis of social network by published continents.

3.4.2. Social Participation

As shown in Figure 3B, high social participation increases depression scores, which means that depression decreases (for tools interpreting depression as decreasing as the number increases). The social participation group reported a significant decline in depression compared with the control group (2.77 [1.30, 5.91], p = 0.008, I2 = 97%), and all articles in the analyzed group were cross-sectional studies and the published continents were Eastern (Figure 3B).

Figure 3C1 shows that if there is a lot of social participation, the depression score decreases, which means that depression decreases. There was a significant decrease in depression in the social participation group compared to the control group (0.67 [0.56, 0.80], p < 0.00001, I2 = 93%) (Figure 3C1). Subgroup analysis was performed to reduce heterogeneity. In the subgroup analysis of social participation by research type, cross-sectional studies did not significantly reduce depression (0.47 [0.18, 1.21], p = 0.12, I2 = 95%), whereas longitudinal studies did (0.78 [0.72, 0.86], p < 0.00001, I2 = 82%) (Figure 3C2). In the subgroup analysis of social participation by published continents, depression in the social participation group was significantly reduced compared to the control group in the western (0.76 [0.59, 0.98], p = 0.03) and eastern continents (0.64 [0.52, 0.79], p < 0.0001, I2 = 95%) (Figure 3C3). The effect size of social participation in the eastern (0.64) was larger than that in the western continents (0.76).

3.4.3. Social Connection and Social Network

As shown in Figure 3D1, many social networks increase depression scores. The social network group showed decreased depression compared with the control group (2.40 [1.89, 3.05], p < 0.00001, I2 = 24%), and all analyzed articles were published in Eastern continents (Figure 3D1). Subgroup analysis of social networks by published continents revealed that depression was significantly reduced in cross-sectional studies (2.51 [1.91, 3.29], p < 0.00001, I2 = 34%), but not in longitudinal studies (1.73 [0.84, 3.56], p = 0.14) (Figure 3D2).

Figure 3E1 shows that if there are many social networks, depression scores decrease. There was a significant decrease in depression in the social network group compared to the control group (0.83 [0.76, 0.90], p < 0.00001, I2 = 94%) (Figure 3E1). Subgroup analysis of social networks by research type revealed that depression was significantly reduced in cross-sectional studies (0.77 [0.70, 0.86], p < 0.00001, I2 = 93), but not in longitudinal studies (0.99 [0.97, 1.01], p = 0.36, I2 = 0%) (Figure 3E2). In the subgroup analysis of social networks by published continents, depression in the social network group was significantly reduced compared to the control group in eastern (0.85 [0.78, 0.92], p = 0.0001, I2 = 94%), but not in western continents (0.64 [0.36, 1.12], p = 0.12, I2 = 97%) (Figure 3E3).

4. Discussion

This study is the first to quantitatively synthesize the effect of social support on the elderly in the community using a meta-analysis. We conducted a systematic review of elderly depression in the community and conducted a meta-analysis on what kind of social resources among intervention methods such as social support, social participation, and social network are effective for elderly depression. As a result of the systematic review, which included a total of 52 studies, social support, social participation, and social connection/social network were identified as effective intervention methods for depression in the elderly in the community. In the subgroup analysis of social participation by research type, cross-sectional studies did not significantly reduce depression, whereas longitudinal studies did. Subgroup analysis of social networks by study type revealed that depression significantly decreased in cross-sectional studies but not in longitudinal studies. In the subgroup analysis of social networks by published continents, depression in the social network group was significantly reduced compared to the control group in the eastern, but not in the western continents.

4.1. Social Resources Were Effective Interventions for Depression in the Elderly of the Community

Social support, social participation, and social connection/network were identified as effective intervention methods for depression among the elderly in the community. It is necessary to discuss the results of this study and other research using a systematic review. According to a systematic review, which was already conducted 10 years ago, depression decreased in the group that applied social activities compared to the group that did not receive intervention [44]. However, since the number of trials was small, the results should be interpreted carefully. Nevertheless, the study showed that discussion groups sharing experiences with each other, designed to strengthen social networks and support, could help reduce loneliness among the elderly and increase social contact and social activities of the elderly. The 52 studies analyzed in this review also identified studies on interactions with families and neighbors as well as various programs; in this study, they were classified as social participation, including community and individual levels, and the results were found to have a positive effect on depression in the elderly. Another review paper analyzing 21 papers on depression intervention reported a study in which social support intervention had a small but significant effect on the reduction of depression symptoms, reporting that health manager and problem-solving interventions reduced depression [45]. As in the previous study, a systematic review in 2019 strongly supported the results of this study and confirmed the effect of depression intervention on 53 elderly residents in the community. The results of the study indicated that group-centered interventions and interventions including social factors have a positive effect on the mental health of participants. Therefore, group-based interventions should be considered first when considering that many elderly people have social difficulties [46]. Another recent systematic review found that through a total of 66 studies, social support has structural and functional aspects, and perceived social support is more generally measured than received social support. Social support has various factors depending on the study, but it was concluded that there is a clear association between social support and elderly depression [5]. Mohd et al. [5] classified social support into structural aspects such as marital status and residential environment and functional support such as emotional satisfaction. However, this study divided it into social support, social participation, and social connection/network. In conclusion, the results of the systematic review of the effects of depression intervention for the elderly consistently report that studies related to social support or participation are effective in depression.

4.2. Implications of the Meta-Analysis and Subgroup Analysis Results

We need to pay attention to the meta-analysis results of this study for the application of social support to practically reduce elderly depression. As mentioned in the results section, in this study, the effects were confirmed through meta-analysis by dividing the interventions for depression of the elderly into three categories: social support, social participation, and social connection/network. The overall meta-analysis results conducted in this study were found to indicate that social support interventions, including social support and social participation, help reduce depression. Additionally, the meta-analysis reported that heterogeneity between the studies was high; therefore, an additional subgroup analysis was performed.

The subgroup analysis of social participation intervention by type of study showed that cross-sectional studies did not significantly reduce depression, while longitudinal studies were found to reduce depression. In other words, long-term follow-up studies confirmed that social participation interventions were effective in depression, thus, they confirmed the positive effect of social participation on depression more clearly. This is because the descriptive cross-sectional study investigates at one point, so it is difficult to generalize the cause and result, while longitudinal research is a study that complements the disadvantages of cross-sectional research. Similarly, as a result of subgroup analysis by research type on social network intervention methods, depression did not decrease in cross-sectional studies, but significantly decreased in longitudinal studies. This difference according to the research type suggests that we should avoid simply understanding the meta-analysis results. In addition, the subgroup analysis of published continental social network interventions showed that depression by social network intervention decreased in Asia compared to the control group, but similar results were not found in the West.

In other words, the results of the subgroup meta-analysis conducted in this study can be presented as follows: First, as suggested in the longitudinal studies, social support, social participation, and social connection/network were all effective interventions for depression among the elderly in the community. Second, interventions using social networks can be more effective in Asian countries than in Western countries. Based on this, the following interventions are needed for nurses to promote social support for the elderly in the community. It is to create a center that can monitor the daily life of the elderly, especially the elderly living alone, centered on the community, and to provide a social support system for the elderly and to create a system that can detect high-risk groups such as depression in advance. It is necessary to make efforts to expand the important role of nurses centering on existing community health centers.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of this review is that it is the most recent and comprehensive quantitative synthesis of interventions in terms of social support for depression in the elderly. In particular, this study differs from previous studies in that a review of more effective intervention methods was conducted through meta-analysis by dividing various social supports. In other words, it can be said that the main achievement of this study was to provide practical guidelines for depression interventions for the elderly in the community.

Regarding the limitations of this study, the heterogeneity was high in the studies included in the meta-analysis. However, social support and social participation consistently produce results in the same direction, and it is judged that there will be no difficulty in drawing conclusions. Second, long-term follow-up studies on depression in the elderly are needed, therefore, the current results should be interpreted carefully. Finally, another limitation is that only studies published in English or Korean were used as targets for analysis.

5. Conclusions

The results of this systematic review support the effects of various social support interventions in reducing depression in the elderly living in the community. Various interventions in the reviewed study were divided into social support, social participation, and social connection/network, and a meta-analysis was conducted. According to the meta-analysis, social support was effective in reducing depression among the elderly in the community; therefore, nurses should allow the elderly in the community to create a system that allows them to perceive social support resources and escape negative emotions such as depression by experiencing emotional support and exchange through social participation. However, not all social resources for depression among the elderly in the community can be provided by nurses; hence, it is necessary to speak out so that related social systems can be established.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare10091598/s1, Table S1: Characteristics of the subjects presented in each study; Table S2: Various depression intervention methods.

Author Contributions

S.H.L. and H.L. contributed to the design of the study. S.H.L. and S.Y. undertook the searches and screened studies for eligibility, assessed the quality of the papers, and conducted statistical analyses. S.Y. and H.L. drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Gachon University Research Fund of 2021 (GCU-202103290001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Donovan, N.J.; Blazer, D. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Review and Commentary of a National Academies Report. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuijfzand, S.; Deforges, C.; Sandoz, V.; Sajin, C.-T.; Jaques, C.; Elmers, J.; Horsch, A. Psychological impact of an epidemic/pandemic on the mental health of healthcare professionals: A rapid review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Mann, F.; Lloyd-Evans, B.; Ma, R.; Johnson, S. Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dingle, G.A.; Sharman, L.S.; Haslam, C.; Donald, M.; Turner, C.; Partanen, R.; Lynch, J.; Draper, G.; van Driel, M.L. The effects of social group interventions for depression: Systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 281, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd, T.A.M.T.; Yunus, R.M.; Hairi, F.; Hairi, N.N.; Choo, W.Y. Social support and depression among community dwelling older adults in Asia: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, R.M.; Meng, J.; Hall, E.D. Multilayered social dynamics and depression among older adults: A 10-year cross-lagged analysis. Psychol. Aging 2020, 35, 948–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, J.S.; Zuidersma, M.; Oude Voshaar, R.C.; Zuidema, S.U.; van den Heuvel, E.R.; Stolk, R.P.; Smidt, N. Social relationships and risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2015, 22, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtorta, N.K.; Kanaan, M.; Gilbody, S.; Ronzi, S.; Hanratty, B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart 2016, 102, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Baker, M.; Harris, T.; Stephenson, D. Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality: A Meta-Analytic Review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. 2017 National Survey of Older Koreans; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Sejong, Korea, 2018. Available online: http://repository.kihasa.re.kr/bitstream/201002/30529/1/Policy%20Report%202018-01.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Oh, I.M.; Cho, M.J.; Hahm, B.-J.; Kim, B.-S.; Sohn, J.H.; Suk, H.W.; Jung, B.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, H.A.; Choi, K.B.; et al. Effectiveness of a village-based intervention for depression in community-dwelling older adults: A randomised feasibility study. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-I.; Kim, S.; Eo, Y. A Study of Depression in the Elderly by Individual and Community Effects. Health Soc. Res. 2019, 39, 192–221. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, E.; Han, K.-M.; Chang, J.; Lee, Y.J.; Choi, K.W.; Han, C.; Ham, B.-J. Social participation and depressive symptoms in community-dwelling older adults: Emotional social support as a mediator. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 137, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulat, N.; Gutema, H.; Wassie, G.T. Prevalence of depression and associated factors among elderly people in Womberma District, north-west, Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 136. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Cao, Q.; Shi, Z.; Lin, W.; Jiang, H.; Hou, Y. Social support and depressive symptom disparity between urban and rural older adults in China. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 237, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxman, T.E.; Berkman, L.F.; Kasl, S.; Freeman, D.H.; Barrett, J. Social Support and Depressive Symptoms in the Elderly. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1992, 135, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, D.J.; Ndanzi, T.; Rweyunga, A.P.; George, J.; Mhando, L.; Ngocho, J.S.; Mboya, I.B. Depression and associated factors among geriatric population in Moshi district council, Northern Tanzania. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 25, 1035–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilar-Compte, M.; Giraldo-Rodríguez, L.; Ochoa-Laginas, A.; Gaitan-Rossi, P. Association Between Depression and Elder Abuse and the Mediation of Social Support: A Cross-Sectional Study of Elder Females in Mexico City. J. Aging Health 2017, 30, 559–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bui, B.K.H. The relationship between social network characteristics and depressive symptoms among older adults in the United States: Differentiating between network structure and network function. Psychogeriatrics 2020, 20, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.Y.; Chiou, A.F. Social media usage, social support, intergenerational relationships, and depressive symptoms among older adults. Geriatr. Nurs. 2020, 41, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Y.-Y.; Katigbak, C.; Zhang, N.J.; Dong, X. Association Between Perceived Social Support and Depressive Symptoms Among Community-Dwelling Older Chinese Americans. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2018, 4, 2333721418778194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanoh, D.; Shahar, S.; Yahya, H.M.; Hamid, T.A. Prevalence and Determinants of Depressive Disorders among Community-dwelling Older Adults: Findings from the Towards Useful Aging Study. Int. J. Gerontol. 2016, 10, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.-K.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lue, B.-H.; Hsu, S.-T. Social support and family functioning on psychological symptoms in elderly Chinese. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2007, 44, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Shinkai, S. Correlates of cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms among older adults in Korea and Japan. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2005, 20, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonucci, T.C.; Fuhrer, R.; Dartigues, J.-F. Social relations and depressive symptomatology in a sample of community-dwelling French older adults. Psychol. Aging 1997, 12, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-G.; Park, S. Gender Difference in Risk Factors for Depression in Community-dwelling Elders. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2012, 42, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechakra-Tahiri, S.; Zunzunegui, M.V.; Préville, M.; Dubé, M. Social relationships and depression among people 65 years and over living in rural and urban areas of Quebec. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2009, 24, 1226–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, M.; Richard, L.; Gauvin, L.; Raymond, É. Inventory and analysis of definitions of social participation found in the aging literature: Proposed taxonomy of social activities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 2141–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Xu, Z.; Xu, X.; Qin, X.; Hu, W.; Hu, Z. Association between social capital and depression among older people: Evidence from Anhui Province, China. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Choi, K.; Jeon, G.-S. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Depressive Symptoms among Korean Older Men and Women: Contribution of Social Support Resources. J. Korean Acad. Commun. Health Nurs. 2020, 31, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Inoue, Y.; Shinozaki, T.; Saito, M.; Takagi, D.; Kondo, K.; Kondo, N. Community Social Capital and Depressive Symptoms Among Older People in Japan: A Multilevel Longitudinal Study. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 29, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.W.; Liu, J.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Z. Understanding Rural–Urban Differences in Depressive Symptoms Among Older Adults in China. J. Aging Health 2015, 28, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, M.J.; Harwood, R.H.; Blizard, R.A.; Thomas, A.; Mann, A.H. Social support deficits, loneliness and life events as risk factors for depression in old age. The Gospel Oak Project VI. Psychol. Med. 1997, 27, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.F.; Zeng, W. Exploring risk factors for depression among older men residing in Macau. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 2645–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.F.; Zeng, W. Investigating factors associated with depression of older women in Macau. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 2969–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Yu, M.; Xu, D.; Wang, Q.; Wang, W. Depression in Community-Dwelling Older Adults Living Alone in China: Association of Social Support Network and Functional Ability. Res. Gerontol. Nurs. 2020, 13, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, I. Prevalence of Depression and Its Correlates in Hong Kong’s Chinese Older Adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2005, 13, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.B.; Lee, S.H. Social Support Network Types and Depressive Symptoms Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults in South Korea. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2019, 31, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, L.E.; Yong, Y.Z.; Chng, M.W.X.; Chew, S.H.; Cheng, L.; Chua, Q.H.A.; Yek, J.J.L.; Lau, L.J.F.; Anand, P.; Hoe, J.T.M.; et al. Individual and area-level socioeconomic status and their association with depression amongst community-dwelling elderly in Singapore. Aging Ment. Health 2014, 18, 628–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, M.-T. Prevalence and risk factors for insomnia in community-dwelling elderly in northern Taiwan. J. Clin. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2013, 4, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-Y.; Wong, G.H.; Lum, T.Y.; Lou, V.W.Q.; Ho, A.H.Y.; Luo, H.; Tong, T.L. Neighborhood support network, perceived proximity to community facilities and depressive symptoms among low socioeconomic status Chinese elders. Aging Ment. Health 2015, 20, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.H.-S.; Youm, Y. Exploring the contingent associations between functional limitations and depressive symptoms across residential context: A multilevel panel data analysis. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 24, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.B.; Sanders, S.; Auth, E.A. Loneliness and depression in independent living retirement communities: Risk and resilience factors. Aging Ment. Health 2004, 8, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsman, A.K.; Nordmyr, J.; Wahlbeck, K. Psychosocial interventions for the promotion of mental health and the prevention of depression among older adults. Health Promot. Int. 2011, 26, i85–i107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.; Vu, C.M. Current Depression Interventions for Older Adults: A Review of Service Delivery Approaches in Primary Care, Home-Based, and Community-Based Settings. Curr. Transl. Geriatr. Exp. Gerontol. Rep. 2013, 2, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niclasen, J.; Lund, L.; Obel, C.; Larsen, L. Mental health interventions among older adults: A systematic review. Scand. J. Public Health 2018, 47, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).