Patient Active Approaches in Osteopathic Practice: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Search strategy,

- Select the studies.

2.1. Identifying the Research Questions

2.2. Identifying the Relevant Studies

2.2.1. Search Strategy

2.2.2. Select Studies

2.3. Collecting, Summarizing, and Reporting Results

3. Results

3.1. Fascia-Oriented Active Approach

3.2. Integrated Mental Imagery and Work-In Exercise

3.3. Mindfulness-Based Exercise

3.4. Gamification and Problem-Solving in the Inter-Enactive Dyadic Approach

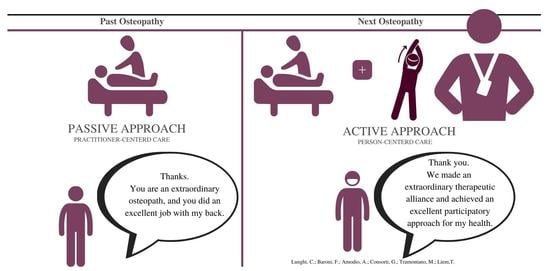

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Phases | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Assessment | The diagnostic process in the osteopathic practice is conducted in a shared decision-making process [41,42,43]. The functional examination of body systems, objective examination tests, and tests of the patient’s responsiveness to provocation can be tools for assessing the impact of somatic dysfunction on the patient’s presentation and for tailoring the treatment to the patient’s needs. The impact of palpatory findings on the patient’s perception (e.g., provocation tests) can act as decision-making drivers, guiding the selection of both osteopathic manipulative techniques and the patient’s active approaches (e.g., exercises) [43]. Pleasant response to touch activates the brain’s interoceptive network, modulating pain and anxiety [42]. Conversely, unpleasant experiences can increase sickness behavior and symptoms [42]. A patient’s responsiveness to slow and light compression types of touch focused on deformation along tangential vectors could be due to tissue changes in the joint capsule’s fibers, affecting, among other things, Ruffini mechanoreceptors [42]. In cases like this, osteopathic techniques such as myofascial release and PAOA with slow movements with myotatic reflex activation and melting stretches are indicated [42]. Conversely, positive responsiveness to slow elongation touch associated with a muscular contraction could be attributable to the internal layer of the joint capsule and the involvement of Golgi mechanoreceptors; in this case, hands-on approaches such as muscle energy technique, associated with Hanna’s pandiculation exercises and active resistant stretches could be selected [42]. In other scenarios, the osteopath is not able to recognize emergent patterns because provocation tests on the clinically relevant area do not evoke improvement in the patient’s responsiveness [42]. This could be a sign of central sensitization with an over-stimulation of fascial mechanoreceptors (mostly free nerve endings) that lead to autonomic nervous system and interoceptive networks firing, also altering the tonus of fascial smooth muscle cells. So-called interoceptive hands-on approaches, such as total body myofascial unwinding, could be administered in a combination of gentle touch, stretching, ideomotor movement, and mindfulness-based strategies in order to improve body awareness [42]. |

| Osteopathic care | Osteopathic manipulative techniques are administered according to osteopathic palpatory findings that emerge as clinically relevant in the decision-making process. The above-mentioned hands-on approaches are followed by patient active osteopathic approaches. In osteopathic practice, active assistive exercises, as well as osteopathic manipulative techniques, can be tailored to the functional tissue alterations related to local adaptations, for example, addressing musculoskeletal and visceral dysfunctions [9]. There are also general techniques and exercises for addressing alterations related to general adaptation [9], for improving systems activities (i.e., autonomic nervous system) [23], and for individual energy management [28]. Osteopathic professionals also incorporate the basic principles of fascia-oriented training [18], archetypal postures [44,45], meditation [28,46], stress management [23], and mindfulness-based exercises [28,47] into patient active exercise approaches. The above-mentioned person-centered approaches are integrated with an evidence-informed component of the treatment plan that is mainly focused on symptoms. |

| Reassessment | The osteopath evaluates the patient’s responsiveness with respect to their condition’s multidimensional aspects. Both patients and practitioners consider reduced or increased levels of familiar symptoms and comparative signs related to osteopathic palpatory findings in order to evaluate the treatment’s immediate effects. |

| Stages | Research Aim | Research Methodology | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Explore different PAOAs used by osteopathic professionals | Defining practitioners’ attitudes and beliefs toward PAOA | Qualitative research (i.e., thematic analysis) |

| 2 | Draw up a theoretical construct and shared model of PAOA | Generate an initial outline of the model for PAOA | Qualitative research (i.e., delphi panel and consensus workshop with grounded theory) |

| 3 | Evaluate potential clinical values of integrating active and PAOA in the treatment plan | Prove the generated model; Evaluate differences in patient-reported outcomes, clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction between subjects who received a passive approach rather than integrative passive and active | Observational studies; Experimental studies (i.e., Case studies, case reports, clinical studies) |

| 4 | Implement the generated model in clinical practice | Communicate the model to students and practitioners in order to implement it in clinical practice | Mentorship, consensus workshops, continuing professional development |

References

- Tramontano, M.; Tamburella, F.; Dal Farra, F.; Bergna, A.; Lunghi, C.; Innocenti, M.; Cavera, F.; Savini, F.; Manzo, V.; D’Alessandro, G. International Overview of Somatic Dysfunction Assessment and Treatment in Osteopathic Research: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tramontano, M.; Pagnotta, S.; Lunghi, C.; Manzo, C.; Manzo, F.; Consolo, S.; Manzo, V. Assessment and Management of Somatic Dysfunctions in Patients with Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2020, 120, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tramontano, M.; Cerritelli, F.; Piras, F.; Spanò, B.; Tamburella, F.; Piras, F.; Caltagirone, C.; Gili, T. Brain Connectivity Changes after Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment: A Randomized Manual Placebo-Controlled Trial. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sciomachen, P.; Arienti, C.; Bergna, A.; Castagna, C.; Consorti, G.; Lotti, A.; Lunghi, C.; Tramontano, M.; Longobardi, M. Core competencies in osteopathy: Italian register of osteopaths proposal. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2018, 27, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEN//TC Project Committee. Services in Osteopathy. Osteopathic Healthcare Provision—Main Element—Complementary Element. CEN/TC 414, ASI, Austria. 2014. Available online: https://www.cen.eu/news/brief-news/pages/news-2016-008.aspx (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- Mistry, R.A.; Bacon, C.J.; Moran, R.W. Attitudes and self-reported practices of New Zealand osteopaths to exercise consultation. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2018, 28, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dun, P.L.S.; Nicolaie, M.A.; Van Messem, A. State of affairs of osteopathy in the Benelux: Benelux Osteosurvey 2013. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2016, 20, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederman, E. A process approach in osteopathy: Beyond the structural model. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2017, 23, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunghi, C.; Tozzi, P.; Fusco, G. The biomechanical model in manual therapy: Is there an ongoing crisis or just the need to revise the underlying concept and application? J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2016, 20, 784–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazzo, M. Ginnastica Interna; Red: Novara, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- DeStefano, L.A. Greenman’s Principles of Manual Medicine, 5th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fulford, D.R. Dr. Fulford’s Touch of Life: The Healing Power of the Natural Life Force; Simon & Schuster Audio: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs Early, K.; Adams, K.M.; Kohlmeier, M. Analysis of nutrition education in osteopathic medical schools. J. Biomed. Ed. 2015, 2015, 376041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargrove, E.J.; Berryman, D.E.; Yoder, J.M.; Beverly, E.A. Assessment of Nutrition Knowledge and Attitudes in Preclinical Osteopathic Medical Students. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2017, 117, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guseman, E.H.; Whipps, J.; Howe, C.A.; Beverly, E.A. First-Year Osteopathic Medical Students’ Knowledge of and Attitudes Toward Physical Activity. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2018, 118, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleip, R.; Müller, D.G. Training principles for fascial connective tissues: Scientific foundation and suggested practical applications. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2013, 17, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calsius, J.; De Bie, J.; Hertogen, R.; Meesen, R. Touching the Lived Body in Patients with Medically Unexplained Symptoms. How an Integration of Hands-on Bodywork and Body Awareness in Psychotherapy may Help People with Alexithymia. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, A.; Franklin, E.; Stecco, C.; Schleip, R. Integrating mental imagery and fascial tissue: A conceptualization for research into movement and cognition. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2020, 40, 101193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minasny, B. Understanding the process of fascial unwinding. Int. J. Ther. Massage Bodyw. 2009, 2, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dorko, B.L. The analgesia of movement: Ideomotor activity and manual care. J. Osteopath. Med. 2003, 6, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallden, M. Rebalancing the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) with work in exercises: Practical applications. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2012, 16, 265–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casals-Gutiérrez, S.; Abbey, H. Interoception, mindfulness and touch: A meta-review of functional MRI studies. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2020, 35, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, G.; Cerritelli, F.; Cortelli, P. Sensitization and Interoception as Key Neurological Concepts in Osteopathy and Other Manual Medicines. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comeaux, Z. Zen awareness in the teaching of palpation: An osteopathic perspective. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2005, 9, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanke, L.; Abbey, H. Developing a new approach to persistent pain management in osteopathic practice. Stage 1: A feasibility study for a group course. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2017, 26, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liem, T.; Neuhuber, W. Osteopathic Treatment Approach to Psychoemotional Trauma by Means of Bifocal Integration. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2020, 120, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liem, T.; Lunghi, C. Reconceptualizing Principles and Models in Osteopathic Care: A Clinical Application of the Integral Theory. Altern. Ther. Health. Med. 2021; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Comeaux, Z. Facilitated oscillatory release—A dynamic method of neuromuscular and ligamentous/articular assessment and treatment. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2005, 9, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebenson, D.C. Gamification. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2018, 22, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteves, J.E.; Cerritelli, F.; Kim, J.; Friston, K.J. Osteopathic Care as (En)active Inference: A Theoretical Framework for Developing an Integrative Hypothesis in Osteopathy. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 812926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijs, J.; Paul van Wilgen, C.; Van Oosterwijck, J.; van Ittersum, M.; Meeus, M. How to explain central sensitization to patients with ‘unexplained’ chronic musculoskeletal pain: Practice guidelines. Man. Ther. 2011, 16, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Akabas, S.R.; Douglas, P.; Kohlmeier, M.; Laur, C.; Lenders, C.M.; Levy, M.D.; Nowson, C.; Ray, S.; Pratt, C.A.; et al. Nutrition competencies in health professionals’ education and training: A new paradigm. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederman, E. The fall of the postural-structural-biomechanical model in manual and physical therapies: Exemplified by lower back pain. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2011, 15, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, K.J. Words matter: The prevalence of chiropractic-specific terminology on Australian chiropractors’ websites. Chiropr. Man. Therap. 2020, 28, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fryer, G. Integrating osteopathic approaches based on biopsychosocial therapeutic mechanisms. Part 2: Clinical approach. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2017, 26, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berceli, D.; Napoli, M. A Proposal for a Mindfulness-Based Trauma Prevention Program for Social Work Professionals. Complement. Health Pract. Rev. 2006, 11, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagna, C.; Consorti, G.; Turinetto, M.; Lunghi, C. Osteopathic Models Integration Radar Plot: A Proposed Framework for Osteopathic Diagnostic Clinical Reasoning. J. Chiropr. Humanit. 2021, 28, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baroni, F.; Tramontano, M.; Barsotti, N.; Chiera, M.; Lanaro, D.; Lunghi, C. Osteopathic structure/function models renovation for a person-centered approach: A narrative review and integrative hypothesis. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2021; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunghi, C.; Baroni, F. Cynefin Framework for Evidence-Informed Clinical Reasoning and Decision-Making. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2019, 119, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroni, F.; Ruffini, N.; D’Alessandro, G.; Consorti, G.; Lunghi, C. The role of touch in osteopathic practice: A narrative review and integrative hypothesis. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2021, 42, 101277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunghi, C.; Consorti, G.; Tramontano, M.; Esteves, J.E.; Cerritelli, F. Perspectives on tissue adaptation related to allostatic load: Scoping review and integrative hypothesis with a focus on osteopathic palpation. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2020, 24, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, P. The contractile field—A new model of human movement—Part 2. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2008, 12, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallden, M.; Sisson, M. Biomechanical attractors—A paleolithic prescription for tendinopathy & glycemic control. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2019, 23, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liem, T. Osteopathy and (hatha) yoga. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2011, 15, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Abbey, H.; Nanke, L. Developing a chronic pain self-management clinic at the British School of Osteopathy: Quantitative pilot study results. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2013, 16, e11–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Keywords: manipulation, osteopathic; musculoskeletal manipulations; exercise movement techniques; exercise therapy; mind-body therapies; bodyworks; mindfulness; meditation; fascia. | |||

| Pubmed search builder: (((((((“Manipulation, Osteopathic” [Mesh]) OR “Musculoskeletal Manipulations” [Mesh]) AND “Exercise Movement Techniques” [Mesh]) OR “Exercise Therapy” [Mesh]) OR “Mind-Body Therapies” [Mesh]) OR “Mindfulness” [Mesh]) OR “Meditation” [Mesh]) OR “Fascia” [Mesh] | |||

| Items grouped with respect to theme and subthemes | |||

| 1.Patient active osteopathic approaches. Principles of application and mechanisms of functioning (total n. = 16). | |||

| 1.1. Fascia-oriented active approach (n. = 2). | 1.2. Integrated mental imagery and work-in exercise (n. = 5). | 1.3. Mindfulness-based exercise (n. = 7). | 1.4. Gamification and problem-solving in the inter-enactive dyadic approach (n. = 2). |

| Lunghi et al., 2016 [9] Schleip and Muller, 2013 [18] | Calsius et al., 2016 [19] Abraham et al., 2020 [20] Minasny, 2009 [21] Dorko 2003 [22] Wallden, 2012 [23] | Casals-Gutiérrez and Abbey, 2020 [24] D’Alessandro et al., 2016 [25] Comeaux, 2005 [26] Nanke and Abbey, 2017 [27] Liem and Neuhuber, 2020 [28] Liem and Lunghi, 2021 [29] Comeaux, 2005 [30] | Liebenson 2018 [31] Esteves et al., 2022 [32] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lunghi, C.; Baroni, F.; Amodio, A.; Consorti, G.; Tramontano, M.; Liem, T. Patient Active Approaches in Osteopathic Practice: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10030524

Lunghi C, Baroni F, Amodio A, Consorti G, Tramontano M, Liem T. Patient Active Approaches in Osteopathic Practice: A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2022; 10(3):524. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10030524

Chicago/Turabian StyleLunghi, Christian, Francesca Baroni, Andrea Amodio, Giacomo Consorti, Marco Tramontano, and Torsten Liem. 2022. "Patient Active Approaches in Osteopathic Practice: A Scoping Review" Healthcare 10, no. 3: 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10030524

APA StyleLunghi, C., Baroni, F., Amodio, A., Consorti, G., Tramontano, M., & Liem, T. (2022). Patient Active Approaches in Osteopathic Practice: A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 10(3), 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10030524