Abstract

This literature review aimed to determine the level of burnout, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction, as well as their associated risks and protective factors, in healthcare professionals during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. We reviewed 2858 records obtained from the CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Embase, PsycINFO, PubMed, and Web of Science databases, and finally included 76 in this review. The main results we found showed an increase in the rate of burnout, dimensions of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and compassion fatigue; a reduction in personal accomplishment; and levels of compassion satisfaction similar to those before the pandemic. The main risk factors associated with burnout were anxiety, depression, and insomnia, along with some sociodemographic variables such as being a woman or a nurse or working directly with COVID-19 patients. Comparable results were found for compassion fatigue, but information regarding compassion satisfaction was lacking. The main protective factors were resilience and social support.

1. Introduction

Because healthcare professionals are especially exposed at the frontline of the COVID-19 pandemic, their quality of life has been put at great risk. Among several potentially harmful factors for the health of professionals, some authors have highlighted the lack of access to adequate protective equipment [1], exhaustion resulting from wearing personal protective equipment throughout the working day, the feeling of having inadequate support [2,3], long working hours and unexpected changes in the type of work [4], concern about trapping or infecting their relatives [5], abandoning their homes to avoid infecting their families [6], lack of access to updated information on constantly changing patterns of action [3,7], uncertainty about disease containment [1], and concerns about seeing patients die [5].

Thus, it seems clear that health professionals are under extreme psychological pressure and, consequently, are at risk of developing several psychological symptoms and mental health disorders [3]. For example, a recent review that included data from more than 7000 professionals [4] found that the prevalence of PTSD symptoms and anxiety and depression ranged from 9.6% to 51% and 20% to 75%, respectively. High levels of stress and somatic symptoms were also reported in Italian health professionals in the study by Barello et al. [8]. Furthermore, a study by Kotera et al. [9] in Japan, found that physicians had more mental health disorders, felt more alone, and had less hope and self-compassion compared to the general population.

Therefore, it is not surprising that the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the quality of life of professionals, aggravating pre-existing problems such as burnout. Burnout, or professional burnout, is a syndrome that occurs in service sector workers subjected to stressful situations [10], and can be defined as the “result of chronic stress in the workplace that has not been successfully managed” [11]. The academic literature from the past few decades has revealed that health professionals are especially vulnerable to burnout because their work context is characterized by high-risk decisions, dealing with the public, and expectations of compassion and sensitivity [12]. However, more and more academics and clinicians have pointed out that burnout alone is insufficient to explain the emotional problems presented by practitioners in general healthcare contexts [13,14] or in the field of palliative care, in particular [15,16]. In this sense, a large body of recent evidence now suggests that many healthcare professionals are suffering from compassion fatigue [17,18].

The concept of compassion fatigue was first introduced by Joinson [19] to characterize a state of reduced capacity for compassion as a consequence of exhaustion caused by contact with the suffering of others [20]. Witnessing the suffering of patients without being able to alleviate their discomfort has a high emotional toll on healthcare personnel [21]. The most widespread theoretical model for the study of compassion fatigue is currently the one developed by Beth Stamm [22,23], who defined it as the negative aspect of professional quality of life and divided it into two dimensions: (1) burnout (as previously explained), and (2) secondary trauma, vicarious trauma, or secondary traumatic stress, which refers to negative feelings driven by fear and trauma related to work [23]. This model also studies the opposite pole of compassion fatigue, that is, the positive aspects of professional life, or compassion satisfaction.

Compassion satisfaction occurs when exposure to traumatic and distress-related events produces satisfaction [24] derived from the pleasure of helping others [22] and providing a means to alleviate suffering [24]. Indeed, when helping people and changing their lives is managed appropriately, professionals and caregivers can feel pleasure and satisfaction rather than burnout or compassion fatigue [14]. Therefore, considering the definition of professional quality of life, it seems clear that the circumstances created by the COVID-19 pandemic are a clear threat to the mental health of professionals and may have affected their levels of burnout, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction. In turn, these factors are key to achieving the adequate well-being of healthcare providers [25,26,27,28] and, in turn, can strongly affect the quality of care received by patients and their families [29].

Although several systematic reviews have recently been published on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of healthcare professionals [4,30,31], very few of them specifically included dimensions of professional quality of life such as burnout [32,33,34,35], only one considered indirect trauma [36] and, to the best of our knowledge, none reviewed the evidence on compassion satisfaction. In this context, the main objective of this current work was to understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on burnout, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction among health professionals by systematically reviewing the literature published during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we aimed to answer the following questions, all of them referring to the experience lived during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic:

- What levels of burnout, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction have health professionals who worked during the COVID-19 pandemic experienced?

- What variables (risk factors) were related to the COVID-19 pandemic having a greater negative impact on professional quality of life?

- What variables (protective factors) corresponded to the COVID-19 pandemic having a lower negative impact on professional quality of life?

2. Materials and Methods

To complete this work we conducted a systematic review of the scientific literature, following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [37] (see Online Supplement S1).

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.1.1. Type of Participants

Health professionals (physicians, nurses, nursing assistants, psychologists, etc.) who carried out their professional activities in the health system (such as primary healthcare centers, emergency departments, intensive care units, palliative care units, or COVID-19 services, among others) during the COVID-19 pandemic were considered in this work.

2.1.2. Study Variables

We considered studies that addressed burnout, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction in health professionals who had cared for patients infected by COVID-19.

2.1.3. Study Types

We included quantitative studies (either cross-sectional or longitudinal) with primary data that addressed burnout, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction in healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies published, or that were in press, from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2020, were considered.

2.1.4. Language

Articles published in English or Spanish were included.

2.1.5. Publication Date

Articles published during 2020 (from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2020) were considered.

2.1.6. Exclusion Criteria

The following types of work were excluded: studies that did not consider healthcare professionals; did not include our study variables (burnout, compassion fatigue, and/or compassion satisfaction); did not include quantitative primary data (i.e., single case studies, reviews, letters to the Editor, comments, qualitative studies, etc.); were not published in Spanish or English; were not published during the year 2020; and that included data from before the COVID-19 pandemic, even when the work met all the inclusion criteria.

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

We searched the CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Embase, PsycINFO, PubMed, and Web of Science databases for relevant articles. Thus, we only used reliable, peer-reviewed databases, platforms, and sources with search tools that allowed us to access the study dates, and thereby, systematically identify studies. These databases included academic literature related to various health disciplines, including health psychology, and therefore represented reliable sources of expert research and information.

The keywords we used were:

- Pandemic or COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2 or Coronavirus, as well as the synonyms for these terms included in the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) database; and

- Burnout or compassion fatigue or stress disorders or compassion satisfaction, as well as the synonyms for these terms included in the MeSH; and

- Health personnel or nursing staff or nurses or physicians or psychology, as well as the synonyms for these terms included in the MeSH.

A list of the terms found in the MeSH, together with the equation we used in the final search, is provided in Online Supplement S2.

Regarding the review procedure, first we entered the search equation into each of the databases, filtering them by publication date (1 January 2020 to 31 December 2020) to narrow the results based on the eligibility criteria. Second, the eligible papers were identified based on their title and keywords as well as whether they met the inclusion criteria. Third, we read the abstracts, reserving any studies we believed met the inclusion criteria. Finally, the full texts of these articles were obtained and read. After this reading, we chose the final records for inclusion and performed the data synthesis.

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

The data from the publications obtained in the search strategy were extracted into an Excel template that was modified according to the studies we reviewed. The metadata included the author(s), year of publication, country of study, main study objective, design, sample size, types of participating professionals, distribution by gender, mean age, other sample characteristics, assessment instruments, metrics used for each variable, descriptive and inferential results relative to the prevalence, data collection date, risk factors and protective variables for burnout, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction. Specifically:

- Means and standard or median deviations and interquartile ranges (for quantitative data), frequencies and percentages (for categorical data) of the prevalence data for burnout, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction.

- To study the risk factors and protective variables of burnout, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction, chi-squared tests, contrast of means, and analysis of variance (for categorical variables), Pearson correlations, Spearman correlations, and simple and multiple regressions (for quantitative variables) were used.

3. Results

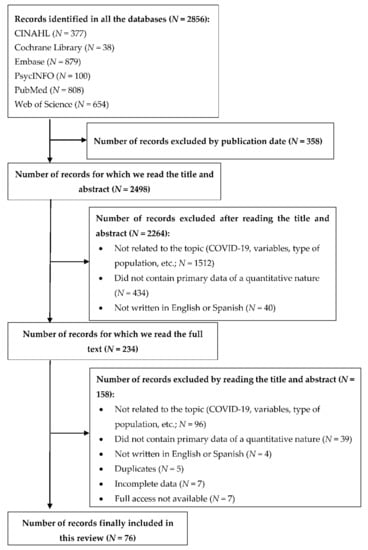

When applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria to the results from the six databases, the search equation produced 2856 records. As shown in Figure 1, these were reduced to 2498 records once the publication date was limited. We reviewed all these entries, first by title and then by abstract, leaving a total of 234 total records for full text review. Most of these were excluded because they did not meet one or more of the inclusion criteria (i.e., health professional participants, burnout, compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction variables, etc.). After reading the full texts of all these entries, 76 records were retained for inclusion in this review. The main characteristics of these tests are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Article selection flow chart.

Table 1.

The main characteristics of the studies included in this systematic review.

The research included in this review was all carried out between February and May 2020, with most of the studies having collected data between March and April (that is, Kannampallil et al. [72]; Ruiz-Fernández et al. [95]; Trumello et al. [101]). Most of the study samples included 100 to 400 participants; Chen et al. [48] included the largest number of participants (12,596 people), while the smallest study cohort was limited to 80 participants [59]. As shown in Table 1, physicians and nurses were the most-studied groups, either separately or together, during the health crisis caused by SARS-CoV-2. In addition, several researchers also focused on other medical professionals including residents, assistants, administrative personnel, physiotherapists, and laboratory technicians, among others. In terms of gender, the samples in 83.4% of the studies comprised more than 50% women, with only 16.4% of the articles including more men than women [39,41,42,50,51,52,54,56,64,74,89,94].

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health professionals of different nationalities was also studied. The most-examined country was the United States of America, with 15 studies [38,49,50,52,56,65,72,73,75,81,86,92,94,104,109]. The two European countries in which the effects of COVID-19 were most studied were Italy and Spain, with eleven [8,43,45,55,57,66,67,68,93,101,102] and seven articles [44,62,78,82,83,84,95,98], respectively.

Regarding the study variables, burnout was studied in 67 (88%) of the papers included in this review, most often with the Maslach Burnout Inventory [8,40,42,43,46,48,54,55,56,57,58,60,68,70,78,84,85,87,88,89,92,93,96,97,104,105,106,107,109,110]. A total of 61% of the studies used the aforementioned questionnaire or one of its derivatives: the aMBI [52,74,75], CMBI [7,48], Mini-z MBI [50,51], MBI-HHS [39,71,82,90,108], or PWLS [73]. Other authors developed an ad-hoc questionnaire [94,103] or used instruments such as the CBI [49,63,66,67,76], OLBI [53,65,69,100], ProQOL [45,62], PFI [61,72,109] or CESQT [83,98]. The highest burnout found in the reviewed studies was been for infectious disease physicians in the Republic of Korea, with 90% of them presenting burnout [90]. The lowest burnout was found in a study carried out in Spain, in which burnout was present in 20.4% of health professionals [84].

The average level of burnout among healthcare professionals was high, especially on the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization subscales [7,39,43,52,63,64,71,88]. Some studies indicated high scores as a consequence of the pandemic on the personal accomplishment subscale [75,78], although these were lower in other studies [7,39,52,60,84]. Numerous reports pointed out the influence that some variables had on the perception of burnout, although 31% (24) of the studies that evaluated burnout did not study its relationship with other variables. The most-studied variables were gender, profession, and workplace (COVID-19/frontline rooms vs. non-COVID-19/secondline rooms). Women showed higher scores on the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization subscales [43,51,76,85,90,93,96,103,110].

Regarding the professional category, higher burnout scores were reported for nurses in several articles [46,49,65,85,100,103], although others pointed towards higher levels of burnout among physicians [62,94]. In terms of the workplace, the results were also contradictory; some research indicated that health workers on the frontline against COVID-19 suffered less burnout [58,104], while the majority found higher burnout scores among these same health workers [40,63,69,72,93,95,101,106,109]. Compared to the general population, healthcare personnel showed higher burnout scores [55,80]. The number of patients attended to also appeared to influence the level of exhaustion: the more COVID-19 patients seen by the participants, the higher their levels of exhaustion [54].

The risk factors, or those that showed a positive relationship with burnout, were anxiety and depression [82,106,108], insomnia [96,106], and moral damage [106]. Work stress also influenced burnout [69] and the lack of personal protective equipment affected emotional exhaustion [39,57]. Protective factors, or those whose presence was related to lower levels of burnout, included resilience and social support [70], and quality of life [46]. In addition, two studies observed that different interventions positively affected the levels of burnout in health workers. For example, Dincer and Inangil [59] implemented a program of emotional freedom techniques that reduced the level of burnout in healthcare personnel. Likewise, Lee et al. [79] found that following a coping strategies program resulted in lower levels of burnout among healthcare professionals. Finally, positive correlations were observed between burnout and secondary trauma or compassion fatigue [45].

Compassion fatigue was also studied in 16 (21%) of the studies included in the review. Of note, some studies referred to the concept as compassion fatigue [62,66,91,95,101,109] while others referred to it as secondary or vicarious trauma [17,38,44,45,67,77,80,97,101,102]. The instruments most used to assess these variables were the ProQOL-5 [45,62,66,81,91,95,101] and STSS [17,97,102]. The levels of compassion fatigue or vicarious trauma found in healthcare professionals were generally high [17,44,45,91,101], although in specific studies they were medium [38] or low [62].

Regarding the protective and risk factors for compassion fatigue, again, the studies we considered focused on variables such as gender, profession, or workplace. Specifically, working with COVID-19 patients tended to increase secondary trauma scores [44,109]. Being a woman was also associated with higher levels of compassion fatigue [17,91]. Additionally, the professional category seemed to influence the perception of fatigue, although the results were inconclusive. Physicians showed higher compassion fatigue scores in the study by Ruiz-Fernández et al. [95]. Franza et al. [67] found that mental health workers had higher compassion fatigue scores, while the groups of therapists and nurses showed reduced compassion fatigue and lower scores on the burnout and secondary trauma subscales with respect to groups of physicians and psychologists. In any case, studies of this nature were scarce.

Finally, compassion satisfaction was only studied in four (5%) of the studies included in this current review [45,62,91,95] and the ProQOOL-5 questionnaire [23] was used to assess this factor in all these studies. In terms of the levels of compassion satisfaction, the study by Buselli et al. [45] found mean levels of 38.2 ± 7.0 for the sample of physicians and nurses. Along the same lines, Dosil et al. [62], reported high (33.2%) or medium (63.1%) levels of compassion satisfaction in health professionals. The latter authors also observed a relationship between compassion satisfaction and professional category, with higher levels of compassion satisfaction being reported in medical assistants/technicians compared to nurses and physicians. In contrast, Ruiz-Fernandez et al. [95] found that nurses had higher scores for compassion satisfaction than physicians. The last study that evaluated compassion satisfaction did not provide descriptive or inferential data in this regard [91].

4. Discussion

The main objective of this work was to understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the quality of life of healthcare professionals, specifically in terms of burnout, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction. To this end, we carried out a systematic review of the literature produced during the first year of the pandemic (2020) which, after screening 2856 records, finally included 76 research papers. The main characteristics of the samples included in the reviewed studies agreed with those previously reported for health professionals in other systematic reviews, in which nurses and women predominated as the main participants [111,112,113]. Considering the results we obtained, it is evident that burnout is still used as the main indicator of emotional well-being in health professionals, much more so than other variables such as fatigue and compassion satisfaction that are used in the more recent literature. The data in this review coincided with those from Mol et al. [113], in which 88% of the articles they examined evaluated exhaustion, while compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction was considered only in 21% and 5% of the cases, respectively.

Regarding the effect of the pandemic on health workers, we observed a worsening of the level of burnout. Specifically, in many of the studies [7,39,43,52,63,64,71,88], the scores for emotional exhaustion and depersonalization exceeded the medium–high levels obtained in pre-pandemic reviews [111,114,115]. However, for certain professional profiles such as healthcare professionals in the oncology area, elevated levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization had already been identified prior to the pandemic [116]. Of note in this present review was the fact that, compared to previous reviews which described very heterogeneous prevalences ranging from 0% to 80% [117], the levels of burnout in the studies we considered were more homogeneous, ranging from 30% to 60% [39,43,55,71].

In the same way that burnout increased in health professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic, an increase in compassion fatigue or vicarious trauma was also observed during the same period. Coinciding with the review by Xie et al. [118] implemented in emergency nurses before the COVID-19 pandemic, our results suggest that healthcare professionals had high scores for compassion fatigue [17,44,45,91,95,101], although other studies [38] have reported medium levels for this factor. In contrast, reviews conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic found moderate levels of compassion fatigue among healthcare workers [114,115]. However, very little data regarding compassion satisfaction were available, and some of these studies were inconclusive [91]. The levels of compassion satisfaction were generally medium or high [62], and were similar to those from before the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, the data collected by Xie et al. [118] from 2015 to 2019, found medium compassion satisfaction levels among oncology nurses.

Regarding the risk factors for developing burnout, our results indicate that the variables that influenced professional quality of life were gender (female sex), profession (nursing), and the workplace (attending or not attending patients with COVID-19). Indeed, the first two risk factors have already been recorded elsewhere in the literature [111,119]. Other variables that emerged as risk factors in this current review included anxiety, depression, and insomnia. Along the same lines, Gómez-Urquiza et al. [116] also highlighted these same risk factors for burnout. Furthermore, the same risk factors have also been observed for compassion fatigue. Finally, given the scarcity of results, we were unable to detect risk or protective factors for compassion satisfaction. In agreement with results from before the pandemic, the protective factors against burnout detected in this review included resilience, social support, and participating in interventions to reduce burnout. For example, in research on resilience and burnout, Heath et al. [120] found that preventive strategies, self-care, organizational justice, and having individual and organizational preventive strategies were protective factors against the development of emotional exhaustion. In fact, these interventions were already being implemented, and were equally effective before the COVID-19 pandemic [113].

Finally, it is worth highlighting both the strengths and limitations of this present study. Of note, although some literature reviews from prior to the pandemic focused on burnout among healthcare professionals, very few studies evaluated compassion fatigue, and even fewer studied the effect of compassion satisfaction. Reviews that focused on the impact of COVID-19 were much scarcer, with only one considering compassion fatigue and none having reviewed the literature on compassion satisfaction. Additionally, even though research focusing on burnout was more abundant, a much higher proportion of the relevant academic literature was considered in this present review. For example, the review by Sharifi et al. [35] on burnout among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic only included 12 studies; Chew et al. considered 23 studies evaluating emotional exhaustion and other variables; and Amanullah and Ramesh [32] only included five articles. Similarly, the only review available on vicarious trauma only included seven studies [36] compared to the 16 considered in this present review. Regarding the limitations of our work, we did not assess the quality of the articles we included in this review. Furthermore, to facilitate the synthesis of the results, we only included quantitative studies; therefore we may have excluded qualitative studies containing relevant information. In this sense, future work could assess the information collected in these qualitative studies.

5. Conclusions

Based on the results of our work, and in light of the literature we reviewed, we concluded that the quality of life of health professionals was significantly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, burnout levels increased from medium–high to high and compassion fatigue went from medium to high. Healthcare professionals reported high rates of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, low personal accomplishment, and compassion fatigue, and low rates of compassion satisfaction. In addition, given that research from all five continents was included in this review, these findings can be considered global.

Therefore, in light of the results, we can say that the vulnerability of healthcare professionals to processes such as burnout or compassion fatigue has increased even more as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. These problems, in addition to affecting the quality of care provided by health personnel, have a negative impact on professionals’ well-being and quality of life; this can aggravate the lack of health professionals that health systems have suffered around the world for decades. Of note, the risk factors and protective factors have not changed compared to previous findings, meaning that we already have the scientific knowledge required to implement interventions to mitigate the empathic burnout of our healthcare professionals. We can no longer afford not to implement preventive strategies to prevent processes such as burnout and compassion fatigue in health professionals.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare10020364/s1, Supplement S1 PRISMA checklist, Supplement S2 Keywords and search terms used in the systematic review.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L. and L.G.; methodology, L.G. and C.L.; formal analysis, C.L., P.D. and L.G.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L. and P.D.; writing—review and editing, L.G. and N.S.; supervision, L.G.; project administration, L.G. and N.S.; funding acquisition, L.G. and N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by project RTI2018-094089-I00, ‘Longitudinal study of compassion and other professional quality of life determinants: national level research on palliative care professionals’ (CompPal) [Estudio longitudinal de la compasión y otros determinantes de la calidad de vida profesional: Una investigación en profesionales de cuidados paliativos a nivel nacional (Comp Pal)] from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación/Agencia Estatal de Investigación/FEDER.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pfefferbaum, B.; North, C.S. Mental Health and the COVID-19 Pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Wang, E.; Jin, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yu, C.; Luo, C.; Zhang, L.; et al. COVID-19 Outbreak Can Change the Job Burnout in Health Care Professionals. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajkumar, R.P. COVID-19 and Mental Health: A Review of the Existing Literature. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 52, 102066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galli, F.; Pozzi, G.; Ruggiero, F.; Mameli, F.; Cavicchioli, M.; Barbieri, S.; Canevini, M.P.; Priori, A.; Pravettoni, G.; Sani, G.; et al. A Systematic Review and Provisional Metanalysis on Psychopathologic Burden on Health Care Workers of Coronavirus Outbreaks. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 568664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Tu, B.; Ma, J.; Chen, L.; Fu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Zhuang, Q. Psychological Impact and Coping Strategies of Frontline Medical Staff in Hunan between January and March 2020 during the Outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei, China. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e924171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Şahin, C.U.; Kulakaç, N. Exploring Anxiety Levels in Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic: Turkey Sample. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-Y.; Yang, Y.-Z.; Zhang, X.-M.; Xu, X.; Dou, Q.-L.; Zhang, W.-W.; Cheng, A.S.K. The Prevalence and Influencing Factors in Anxiety in Medical Workers Fighting COVID-19 in China: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Epidemiol. Infect. 2020, 148, e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barello, S.; Palamenghi, L.; Graffigna, G. Burnout and Somatic Symptoms among Frontline Healthcare Professionals at the Peak of the Italian COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Ozaki, A.; Miyatake, H.; Tsunetoshi, C.; Nishikawa, Y.; Tanimoto, T. Mental Health of Medical Workers in Japan during COVID-19: Relationships with Loneliness, Hope and Self-Compassion. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 6271–6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberger, H.J. Staff Burn-Out. J. Soc. Issues 1974, 30, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization CIE-11. Available online: https://icd.who.int/es (accessed on 7 January 2022).

- Burton, A.; Burgess, C.; Dean, S.; Koutsopoulou, G.Z.; Hugh-Jones, S. How Effective Are Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Reducing Stress among Healthcare Professionals? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Stress Health J. Int. Soc. Investig. Stress 2017, 33, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bride, B.E.; Radey, M.; Figley, C.R. Measuring Compassion Fatigue. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2007, 35, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figley, C.R. Compassion Fatigue: Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder in Those Who Treat the Traumatized; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0-203-77738-1. [Google Scholar]

- Galiana, L.; Sansó, N.; Muñoz-Martínez, I.; Vidal-Blanco, G.; Oliver, A.; Larkin, P.J. Palliative Care Professionals’ Inner Life: Exploring the Mediating Role of Self-Compassion in the Prediction of Compassion Satisfaction, Compassion Fatigue, Burnout and Wellbeing. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 63, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansó, N.; Galiana, L.; Oliver, A.; Pascual, A.; Sinclair, S.; Benito, E. Palliative Care Professionals’ Inner Life: Exploring the Relationships among Awareness, Self-Care, and Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue, Burnout, and Coping with Death. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2015, 50, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpacioglu, S.; Gurler, M.; Cakiroglu, S. Secondary Traumatization Outcomes and Associated Factors among the Health Care Workers Exposed to the COVID-19. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2021, 67, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahrour, G.; Dardas, L.A. Acute Stress Disorder, Coping Self-Efficacy and Subsequent Psychological Distress among Nurses amid COVID-19. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 1686–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figley, C.R. Compassion Fatigue: Psychotherapists’ Chronic Lack of Self Care. J. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 58, 1433–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, J.; Jackson, D.; Usher, K. Compassion Fatigue in Critical Care Nurses. An Integrative Review of the Literature. Saudi Med. J. 2019, 40, 1087–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamm, B.H. Helping the Helpers Helping the Helpers: Compassion Satisfaction and Compassion Fatigue in Self-Care, Management, and Policy of Suicide Prevention Hotlines. In Resources for Community Suicide Prevention; Idaho State University Article; Idaho State University: Pocatello, ID, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stamm, B.H. Professional Quality of Life Measure: Compassion, Satisfaction, and Fatigue Version 5 (ProQOL); Center for Victim Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, C.; Craig, J.; Janvrin, D.R.; Wetsel, M.A.; Reimels, E. Compassion Satisfaction, Burnout, and Compassion Fatigue among Emergency Nurses Compared with Nurses in Other Selected Inpatient Specialties. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2010, 36, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, M.Y.H.; Chong, P.H.; Neo, P.S.H.; Ong, Y.J.; Yong, W.C.; Ong, W.Y.; Shen, M.L.J.; Hum, A.Y.M. Burnout, Psychological Morbidity and Use of Coping Mechanisms among Palliative Care Practitioners: A Multi-Centre Cross-Sectional Study. Palliat. Med. 2015, 29, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizano, E.L. Examining the Impact of Job Burnout on the Health and Well-Being of Human Service Workers: A Systematic Review and Synthesis. Hum. Serv. Organ. Manag. Leadersh. Gov. 2015, 39, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sansó, N.; Galiana, L.; Oliver, A.; Tomás-Salvá, M.; Vidal-Blanco, G. Predicting Professional Quality of Life and Life Satisfaction in Spanish Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senturk, J.C.; Melnitchouk, N. Surgeon Burnout: Defining, Identifying, and Addressing the New Reality. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 2019, 32, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Panagioti, M.; Geraghty, K.; Johnson, J.; Zhou, A.; Panagopoulou, E.; Chew-Graham, C.; Peters, D.; Hodkinson, A.; Riley, R.; Esmail, A. Association between Physician Burnout and Patient Safety, Professionalism, and Patient Satisfaction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2018, 178, 1317–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Iglesias, J.J.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Martín-Pereira, J.; Fagundo-Rivera, J.; Ayuso-Murillo, D.; Martínez-Riera, J.R.; Ruiz-Frutos, C. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) on the mental health of healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 2020, 94, e202007088. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Ripoll, M.J.; Meneses-Echavez, J.F.; Ricci-Cabello, I.; Fraile-Navarro, D.; Fiol-deRoque, M.A.; Pastor-Moreno, G.; Castro, A.; Ruiz-Pérez, I.; Zamanillo Campos, R.; Gonçalves-Bradley, D.C. Impact of Viral Epidemic Outbreaks on Mental Health of Healthcare Workers: A Rapid Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanullah, S.; Ramesh Shankar, R. The Impact of COVID-19 on Physician Burnout Globally: A Review. Healthcare 2020, 8, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenská, J.; Steinerová, V.; Javůrková, A.; Urits, I.; Kaye, A.D.; Viswanath, O.; Varrassi, G. Occupational Burnout Syndrome and Post-Traumatic Stress among Healthcare Professionals during the Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2020, 34, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restauri, N.; Sheridan, A.D. Burnout and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: Intersection, Impact, and Interventions. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2020, 17, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, M.; Asadi-Pooya, A.A.; Mousavi-Roknabadi, R.S. Burnout among Healthcare Providers of COVID-19; A Systematic Review of Epidemiology and Recommendations. Arch. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2021, 9, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benfante, A.; Di Tella, M.; Romeo, A.; Castelli, L. Traumatic Stress in Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review of the Immediate Impact. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 569935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aafjes-van Doorn, K.; Békés, V.; Prout, T.A.; Hoffman, L. Psychotherapists’ Vicarious Traumatization during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, S148–S150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelhafiz, A.S.; Ali, A.; Ziady, H.H.; Maaly, A.M.; Alorabi, M.; Sultan, E.A. Prevalence, Associated Factors, and Consequences of Burnout among Egyptian Physicians during COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebischer, O.; Weilenmann, S.; Gachoud, D.; Méan, M.; Spiller, T.R. Physical and Psychological Health of Medical Students Involved in the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Response in Switzerland. Swiss. Med. Wkly. 2020, 150, w20418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, S.S.; Shah, S.; Calderon, M.D.; Soin, A.; Manchikanti, L. The Effect of COVID-19 on Interventional Pain Management Practices: A Physician Burnout Survey. Pain Physician 2020, 23, S271–S282. [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay, E.; De Waele, J.; Ferrer, R.; Staudinger, T.; Borkowska, M.; Povoa, P.; Iliopoulou, K.; Artigas, A.; Schaller, S.J.; Hari, M.S.; et al. Symptoms of Burnout in Intensive Care Unit Specialists Facing the COVID-19 Outbreak. Ann. Intensive Care 2020, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barello, S.; Palamenghi, L.; Graffigna, G. Stressors and Resources for Healthcare Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Lesson Learned From Italy. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Donoso, L.M.; Moreno-Jiménez, J.; Amutio, A.; Gallego-Alberto, L.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Garrosa, E. Stressors, Job Resources, Fear of Contagion, and Secondary Traumatic Stress among Nursing Home Workers in Face of the COVID-19: The Case of Spain. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 40, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buselli, R.; Corsi, M.; Baldanzi, S.; Chiumiento, M.; Del Lupo, E.; Dell’Oste, V.; Bertelloni, C.A.; Massimetti, G.; Dell’Osso, L.; Cristaudo, A.; et al. Professional Quality of Life and Mental Health Outcomes among Health Care Workers Exposed to Sars-Cov-2 (COVID-19). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelmeçe, N.; Menekay, M. The Effect of Stress, Anxiety and Burnout Levels of Healthcare Professionals Caring for COVID-19 Patients on Their Quality of Life. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, D.; Jin, Y.; He, M.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, X.; Song, S.; Zhang, L.; Xiang, X.; et al. Risk Factors for Depression and Anxiety in Healthcare Workers Deployed during the COVID-19 Outbreak in China. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Sun, C.; Chen, J.-J.; Jen, H.-J.; Kang, X.L.; Kao, C.-C.; Chou, K.-R. A Large-Scale Survey on Trauma, Burnout, and Posttraumatic Growth among Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chor, W.P.D.; Ng, W.M.; Cheng, L.; Situ, W.; Chong, J.W.; Ng, L.Y.A.; Mok, P.L.; Yau, Y.W.; Lin, Z. Burnout amongst Emergency Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multi-Center Study. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 46, 700–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civantos, A.M.; Bertelli, A.; Gonçalves, A.; Getzen, E.; Chang, C.; Long, Q.; Rajasekaran, K. Mental Health among Head and Neck Surgeons in Brazil during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Study. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2020, 41, 102694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Civantos, A.M.; Byrnes, Y.; Chang, C.; Prasad, A.; Chorath, K.; Poonia, S.K.; Jenks, C.M.; Bur, A.M.; Thakkar, P.; Graboyes, E.M.; et al. Mental Health among Otolaryngology Resident and Attending Physicians during the COVID-19 Pandemic: National Study. Head Neck 2020, 42, 1597–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, J.R.; Abdelsattar, J.M.; Glocker, R.J.; Carmichael, H.; Vigneshwar, N.G.; Ryan, R.; Qiu, Q.; Nayyar, A.; Visenio, M.R.; Sonntag, C.C.; et al. COVID-19 Pandemic and the Lived Experience of Surgical Residents, Fellows, and Early-Career Surgeons in the American College of Surgeons. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2021, 232, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, I.; Almeida, A.E. Organizational Justice, Professional Identification, Empathy, and Meaningful Work during COVID-19 Pandemic: Are They Burnout Protectors in Physicians and Nurses? Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravero, A.L.; Kim, N.J.; Feld, L.D.; Berry, K.; Rabiee, A.; Bazarbashi, N.; Bassin, S.; Lee, T.-H.; Moon, A.M.; Qi, X.; et al. Impact of Exposure to Patients with COVID-19 on Residents and Fellows: An International Survey of 1420 Trainees. Postgrad. Med. J. 2021, 97, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demartini, B.; Nisticò, V.; D’Agostino, A.; Priori, A.; Gambini, O. Early Psychiatric Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on the General Population and Healthcare Workers in Italy: A Preliminary Study. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, K.; Mercuri, M.; Wallner, C.; Clayton, N.; Archambault, P.; Ritchie, K.; Gérin-Lajoie, C.; Gray, S.; Schwartz, L.; Chan, T.; et al. Canadian Emergency Physician Psychological Distress and Burnout during the First 10 Weeks of COVID-19: A Mixed-Methods Study. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2020, 1, 1030–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Monte, C.; Monaco, S.; Mariani, R.; Di Trani, M. From Resilience to Burnout: Psychological Features of Italian General Practitioners during COVID-19 Emergency. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriu, M.C.T.; Pantea-Stoian, A.; Smaranda, A.C.; Nica, A.A.; Carap, A.C.; Constantin, V.D.; Davitoiu, A.M.; Cirstoveanu, C.; Bacalbasa, N.; Bratu, O.G.; et al. Burnout Syndrome in Romanian Medical Residents in Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Med. Hypotheses 2020, 144, 109972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, B.; Inangil, D. The Effect of Emotional Freedom Techniques on Nurses’ Stress, Anxiety, and Burnout Levels during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Explore 2021, 17, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinibutun, S.R. Factors Associated with Burnout among Physicians: An Evaluation during a Period of COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Healthc. Leadersh. 2020, 12, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dosil, M.; Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Redondo, I.; Picaza, M.; Jaureguizar, J. Psychological Symptoms in Health Professionals in Spain after the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 606121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, I.; Teixeira, A.; Castro, L.; Marina, S.; Ribeiro, C.; Jácome, C.; Martins, V.; Ribeiro-Vaz, I.; Pinheiro, H.C.; Silva, A.R.; et al. Burnout among Portuguese Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhadi, M.; Msherghi, A.; Elgzairi, M.; Alhashimi, A.; Bouhuwaish, A.; Biala, M.; Abuelmeda, S.; Khel, S.; Khaled, A.; Alsoufi, A.; et al. Burnout Syndrome among Hospital Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Civil War: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Haj, M.; Allain, P.; Annweiler, C.; Boutoleau-Bretonnière, C.; Chapelet, G.; Gallouj, K.; Kapogiannis, D.; Roche, J.; Boudoukha, A.H. Burnout of Healthcare Workers in Acute Care Geriatric Facilities during the COVID-19 Crisis: An Online-Based Study. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 78, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franza, F.; Basta, R.; Pellegrino, F.; Solomita, B.; Fasano, V. The Role of Fatigue of Compassion, Burnout and Hopelessness in Healthcare: Experience in the Time of COVID-19 Outbreak. Psychiatr. Danub. 2020, 32, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Franza, F.; Pellegrino, F.; Buono, G.D.; Solomita, B.; Fasano, V. Compassion Fatigue, Burnout and Hopelessness of the Health Workers in COVID-19 Pandemic Emergency. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 40, S476–S477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, E.M.; Pedroli, E.; D’Aniello, G.E.; Stramba Badiale, C.; Pietrabissa, G.; Manna, C.; Stramba Badiale, M.; Riva, G.; Castelnuovo, G.; Molinari, E. The Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Outbreak on Health Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarboozi Hoseinabadi, T.; Kakhki, S.; Teimori, G.; Nayyeri, S. Burnout and Its Influencing Factors between Frontline Nurses and Nurses from Other Wards during the Outbreak of Coronavirus Disease -COVID-19- in Iran. Investig. Educ. Enferm. 2020, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Kong, Y.; Li, W.; Han, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, L.X.; Wan, S.W.; Liu, Z.; Shen, Q.; Yang, J.; et al. Frontline Nurses’ Burnout, Anxiety, Depression, and Fear Statuses and Their Associated Factors during the COVID-19 Outbreak in Wuhan, China: A Large-Scale Cross-Sectional Study. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 24, 100424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, S.; Dhandapani, M.; Cyriac, M.C. Burnout and Resilience among Frontline Nurses during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study in the Emergency Department of a Tertiary Care Center, North India. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 24, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannampallil, T.G.; Goss, C.W.; Evanoff, B.A.; Strickland, J.R.; McAlister, R.P.; Duncan, J. Exposure to COVID-19 Patients Increases Physician Trainee Stress and Burnout. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelker, H.; Yoder, K.; Musey, P.; Harris, M.; Johnson, O.; Sarmiento, E.; Vyas, P.; Henderson, B.; Adams, Z.; Welch, J.L. Longitudinal Prospective Study of Emergency Medicine Provider Wellness across Ten Academic and Community Hospitals during the Initial Surge of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Res. Sq. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalafallah, A.M.; Lam, S.; Gami, A.; Dornbos, D.L.; Sivakumar, W.; Johnson, J.N.; Mukherjee, D. Burnout and Career Satisfaction among Attending Neurosurgeons during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2020, 198, 106193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalafallah, A.M.; Lam, S.; Gami, A.; Dornbos, D.L.; Sivakumar, W.; Johnson, J.N.; Mukherjee, D. A National Survey on the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic upon Burnout and Career Satisfaction among Neurosurgery Residents. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 80, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasne, R.W.; Dhakulkar, B.S.; Mahajan, H.C.; Kulkarni, A.P. Burnout among Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic in India: Results of a Questionnaire-Based Survey. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 24, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, S.R.; Saeed, I.; Rehman, S.U.; Fayaz, M. Impact of Fear of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Nurses in Pakistan. J. Loss Trauma 2021, 26, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázaro-Pérez, C.; Martínez-López, J.Á.; Gómez-Galán, J.; López-Meneses, E. Anxiety About the Risk of Death of Their Patients in Health Professionals in Spain: Analysis at the Peak of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Rozybakieva, Z.; Asimov, M.; Bagiyarova, F.; Tazhiyeva, A.; Ussebayeva, N.; Tanabayeva, S.; Fakhradiyev, I. Coping Strategy as a Way to Prevent Emotional Burnout in Primary Care Doctors: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Balk. Med. Union 2020, 55, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ge, J.; Yang, M.; Feng, J.; Qiao, M.; Jiang, R.; Bi, J.; Zhan, G.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Vicarious Traumatization in the General Public, Members, and Non-Members of Medical Teams Aiding in COVID-19 Control. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 916–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litam, S.D.A.; Balkin, R.S. Moral Injury in Health-Care Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic. Traumatology 2021, 27, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luceño-Moreno, L.; Talavera-Velasco, B.; García-Albuerne, Y.; Martín-García, J. Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress, Anxiety, Depression, Levels of Resilience and Burnout in Spanish Health Personnel during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano García, G.; Ayala Calvo, J.C. The Threat of COVID-19 and Its Influence on Nursing Staff Burnout. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 832–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-López, J.Á.; Lázaro-Pérez, C.; Gómez-Galán, J.; Fernández-Martínez, M.D.M. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Emergency on Health Professionals: Burnout Incidence at the Most Critical Period in Spain. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, T.; Kobayashi, D.; Taki, F.; Sakamoto, F.; Uehara, Y.; Mori, N.; Fukui, T. Prevalence of Health Care Worker Burnout during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic in Japan. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2017271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.G.; Roberts, K.J.; Hinkson, C.R.; Davis, G.; Strickland, S.L.; Rehder, K.J. Resilience and Burnout Resources in Respiratory Care Departments. Respir. Care 2021, 66, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murat, M.; Köse, S.; Savaşer, S. Determination of Stress, Depression and Burnout Levels of Front-Line Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, K.Y.Y.; Zhou, S.; Tan, S.H.; Ishak, N.D.B.; Goh, Z.Z.S.; Chua, Z.Y.; Chia, J.M.X.; Chew, E.L.; Shwe, T.; Mok, J.K.Y.; et al. Understanding the Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Patients with Cancer, Their Caregivers, and Health Care Workers in Singapore. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2020, 6, 1494–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osama, M.; Zaheer, F.; Saeed, H.; Anees, K.; Jawed, Q.; Syed, S.H.; Sheikh, B.A. Impact of COVID-19 on Surgical Residency Programs in Pakistan; A Residents’ Perspective. Do Programs Need Formal Restructuring to Adjust with the “New Normal”? A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 79, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.Y.; Kim, B.; Jung, D.S.; Jung, S.I.; Oh, W.S.; Kim, S.-W.; Peck, K.R.; Chang, H.-H. The Korean Society of Infectious Diseases Psychological Distress among Infectious Disease Physicians during the Response to the COVID-19 Outbreak in the Republic of Korea. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinho, A.S.; Morales, A.U.; Bernal, M.B.; Villarroel, P.E.V. Sintomatología asociada a trastornos de salud mental en trabajadores sanitarios en Paraguay: Efecto COVID-19. Rev. Interam. Psicol. Interam. J. Psychol. 2020, 54, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, A.; Civantos, A.M.; Byrnes, Y.; Chorath, K.; Poonia, S.; Chang, C.; Graboyes, E.M.; Bur, A.M.; Thakkar, P.; Deng, J.; et al. Snapshot Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Wellness in Nonphysician Otolaryngology Health Care Workers: A National Study. OTO Open 2020, 4, 2473974X20948835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapisarda, F.; Vallarino, M.; Cavallini, E.; Barbato, A.; Brousseau-Paradis, C.; De Benedictis, L.; Lesage, A. The Early Impact of the COVID-19 Emergency on Mental Health Workers: A Survey in Lombardy, Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.M.; Medak, A.J.; Baumann, B.M.; Lim, S.; Chinnock, B.; Frazier, R.; Cooper, R.J. Academic Emergency Medicine Physicians’ Anxiety Levels, Stressors, and Potential Stress Mitigation Measures during the Acceleration Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2020, 27, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Fernández, M.D.; Ramos-Pichardo, J.D.; Ibáñez-Masero, O.; Cabrera-Troya, J.; Carmona-Rega, M.I.; Ortega-Galán, Á.M. Compassion Fatigue, Burnout, Compassion Satisfaction and Perceived Stress in Healthcare Professionals during the COVID-19 Health Crisis in Spain. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 4321–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin Sayilan, A.; Kulakaç, N.; Uzun, S. Burnout Levels and Sleep Quality of COVID-19 Heroes. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2021, 57, 1231–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secosan, I.; Virga, D.; Crainiceanu, Z.P.; Bratu, T. The Mediating Role of Insomnia and Exhaustion in the Relationship between Secondary Traumatic Stress and Mental Health Complaints among Frontline Medical Staff during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto-Rubio, A.; Giménez-Espert, M.D.C.; Prado-Gascó, V. Effect of Emotional Intelligence and Psychosocial Risks on Burnout, Job Satisfaction, and Nurses’ Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiller, T.R.; Méan, M.; Ernst, J.; Sazpinar, O.; Gehrke, S.; Paolercio, F.; Petry, H.; Pfaltz, M.C.; Morina, N.; Aebischer, O.; et al. Development of Health Care Workers’ Mental Health during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in Switzerland: Two Cross-Sectional Studies. Psychol. Med. 2020, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, B.Y.Q.; Kanneganti, A.; Lim, L.J.H.; Tan, M.; Chua, Y.X.; Tan, L.; Sia, C.H.; Denning, M.; Goh, E.T.; Purkayastha, S.; et al. Burnout and Associated Factors among Health Care Workers in Singapore during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 1751–1758.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trumello, C.; Bramanti, S.M.; Ballarotto, G.; Candelori, C.; Cerniglia, L.; Cimino, S.; Crudele, M.; Lombardi, L.; Pignataro, S.; Viceconti, M.L.; et al. Psychological Adjustment of Healthcare Workers in Italy during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Differences in Stress, Anxiety, Depression, Burnout, Secondary Trauma, and Compassion Satisfaction between Frontline and Non-Frontline Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vagni, M.; Maiorano, T.; Giostra, V.; Pajardi, D. Coping With COVID-19: Emergency Stress, Secondary Trauma and Self-Efficacy in Healthcare and Emergency Workers in Italy. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahlster, S.; Sharma, M.; Lewis, A.K.; Patel, P.V.; Hartog, C.S.; Jannotta, G.; Blissitt, P.; Kross, E.K.; Kassebaum, N.J.; Greer, D.M.; et al. The Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic’s Effect on Critical Care Resources and Health-Care Providers: A Global Survey. Chest 2021, 159, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Luo, C.; Hu, S.; Lin, X.; Anderson, A.E.; Bruera, E.; Yang, X.; Wei, S.; Qian, Y. A Comparison of Burnout Frequency among Oncology Physicians and Nurses Working on the Frontline and Usual Wards during the COVID-19 Epidemic in Wuhan, China. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 60, e60–e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yörük, S.; Güler, D. The Relationship between Psychological Resilience, Burnout, Stress, and Sociodemographic Factors with Depression in Nurses and Midwives during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study in Turkey. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2021, 57, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbini, G.; Ebigbo, A.; Reicherts, P.; Kunz, M.; Messman, H. Psychosocial Burden of Healthcare Professionals in Times of COVID-19—A Survey Conducted at the University Hospital Augsburg. GMS Ger. Med. Sci. 2020, 18, Doc05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Pan, W.; Zheng, J.; Gao, J.; Huang, X.; Cai, S.; Zhai, Y.; Latour, J.M.; Zhu, C. Stress, Burnout, and Coping Strategies of Frontline Nurses during the COVID-19 Epidemic in Wuhan and Shanghai, China. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhizhong, W.; Koenig, H.G.; Yan, T.; Jing, W.; Mu, S.; Hongyu, L.; Guangtian, L. Psychometric Properties of the Moral Injury Symptom Scale among Chinese Health Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagherian, K.; Steege, L.M.; Cobb, S.J.; Cho, H. Insomnia, Fatigue and Psychosocial Well-Being during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Hospital Nursing Staff in the United States. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, M.; Joo, S.; Couette, P.-A.; de Jaegher, S.; Joly, F.; Humbert, X. Impact on Mental Health of the COVID-19 Outbreak among Community Pharmacists during the Sanitary Lockdown Period. Ann. Pharm. Fr. 2020, 78, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobson, H.; Malpas, C.B.; Burrell, A.J.; Gurvich, C.; Chen, L.; Kulkarni, J.; Winton-Brown, T. Burnout and Psychological Distress amongst Australian Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Australas. Psychiatry Bull. R. Aust. N. Z. Coll. Psychiatr. 2021, 29, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, C.-H.; Tseng, P.-C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Lin, K.-H.; Chen, Y.-Y. Burnout in the Intensive Care Unit Professionals: A Systematic Review. Medicine 2016, 95, e5629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, L.H.; Johnson, J.; Watt, I.; Tsipa, A.; O’Connor, D.B. Healthcare Staff Wellbeing, Burnout, and Patient Safety: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Mol, M.M.C.; Kompanje, E.J.O.; Benoit, D.D.; Bakker, J.; Nijkamp, M.D. The Prevalence of Compassion Fatigue and Burnout among Healthcare Professionals in Intensive Care Units: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, N.; Cockett, G.; Heinrich, C.; Doig, L.; Fiest, K.; Guichon, J.R.; Page, S.; Mitchell, I.; Doig, C.J. Compassion Fatigue in Healthcare Providers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nurs. Ethics 2020, 27, 639–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Campos, E.; Vargas-Román, K.; Velando-Soriano, A.; Suleiman-Martos, N.; Cañadas-de la Fuente, G.A.; Albendín-García, L.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L. Compassion Fatigue, Compassion Satisfaction, and Burnout in Oncology Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Aneas-López, A.B.; Fuente-Solana, E.I.; Albendín-García, L.; Díaz-Rodríguez, L.; Fuente, G.A. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Levels of Burnout Among Oncology Nurses: A Systematic Review. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2016, 43, E104–E120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Torre, M.; Ramos, M.A.; Rosales, R.C.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of Burnout among Physicians: A Systematic Review. JAMA 2018, 320, 1131–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xie, W.; Chen, L.; Feng, F.; Okoli, C.T.C.; Tang, P.; Zeng, L.; Jin, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. The Prevalence of Compassion Satisfaction and Compassion Fatigue among Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 120, 103973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bria, M.; Băban, A.; Dumitrascu, D. Systematic Review of Burnout Risk Factors among European Healthcare Professionals. Cogn. Brain Behav. 2012, 6, 423–452. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, C.; Sommerfield, A.; von Ungern-Sternberg, B.S. Resilience Strategies to Manage Psychological Distress among Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Narrative Review. Anaesthesia 2020, 75, 1364–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, Q.H.; Wei, K.C.; Vasoo, S.; Sim, K. Psychological and Coping Responses of Health Care Workers toward Emerging Infectious Disease Outbreaks: A Rapid Review and Practical Implications for the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2020, 81, 16119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).