Abstract

The Exeter point of a given triangle is the center of perspective of the tangential triangle and the circummedial triangle of the given triangle. The process of the Exeter point from the centroid serves as a base for defining the Exeter transformation with respect to the triangle , which maps all points of the plane. We show that a point, its image, the symmedian, and three exsymmedian points of the triangle are on the same conic. The Exeter transformation of a general line is a fourth-order curve passing through the exsymmedian points. We show that each image point can be the Exeter transformation of four different points. We aim to determine the invariant lines and points and some other properties of the transformation.

MSC:

51A05; 51N15; 51N20; 97G40

1. Introduction

The Exeter point is one of the well-known triangle centers among the over 35,000 centers in the online Encyclopedia of Triangle Centers [1]. The Exeter point of a given triangle is defined from the centroid of the triangle by a drawing process. In this article, as a generalization of the definition of the Exeter point to the whole plane of the triangle, we define a so-called Exeter transformation with respect to a given triangle . We show some properties of this transformation, we give the invariant figures, and we show that certain important points during the transformation lie on a conic.

Minevich and Morton [2] defined a similar, so-called “TCC-perspector”, transformation with respect to , and they gave a nice connection between the isogonal transformation and the “TCC-perspector”. For more details and the history of the Exeter point see, ex., in [1,2,3,4,5,6].

For verifying our statements we use an analytical way with barycentric coordinates. The base triples of this barycentric coordinate system we use the vertices of a given triangle. There are many interesting articles dealing with the use of barycentric coordinates, and among them the works in [7,8,9] may be useful.

2. Exeter Transformation

Let be a triangle and its tangential triangle.

Definition 1

(Exeter point). Let G be the centroid of a triangle . Define to be the point (other than the polygon vertex A), where the triangle median through A meets the circumcircle of , and define and similarly. Three lines— , and —intersect at a point called the Exeter point of triangle ABC.

Therefore, Exeter point is the perspector of the circum-medial triangle , and the tangential triangle .

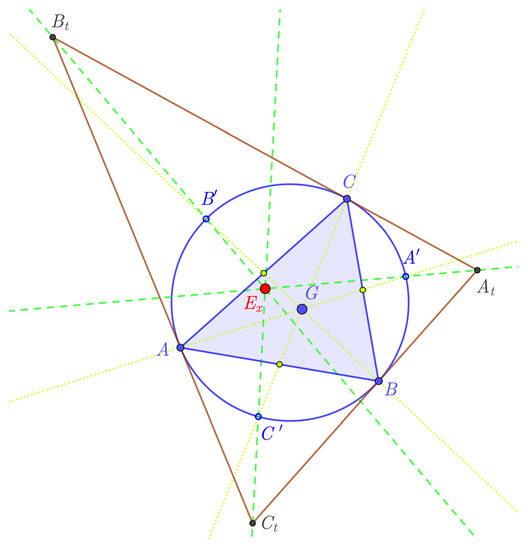

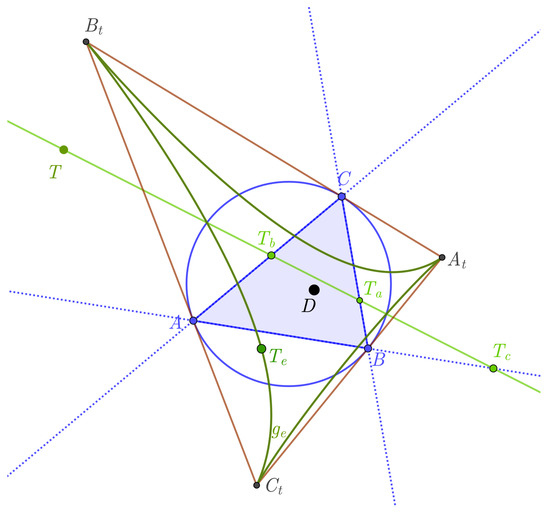

In Figure 1, the centroid of the triangle is signed as G and the Exeter point as point .

Figure 1.

The Exeter point .

The cevian properties of medians and its intersection (centroid) in the previous definition enable us to generalize the point construction process and obtain a new point transformation in connection to a triangle and its tangential triangle :

Definition 2

(Exeter transformation). Let P be an arbitrary point in the plane of the triangle . Define to be the point (other than the polygon vertex A) where the line meets the circumcircle of , and define and similarly. Three lines— , and —intersect at a point .

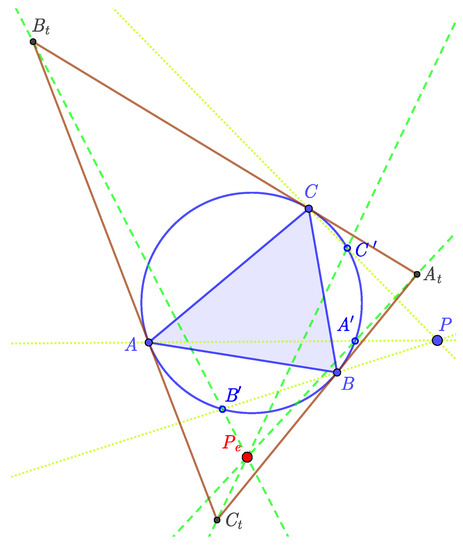

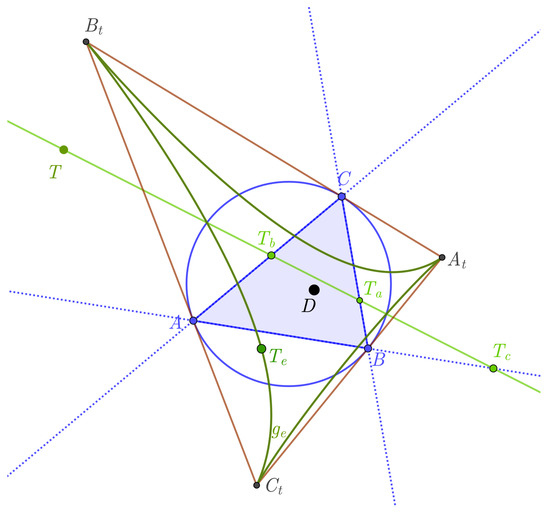

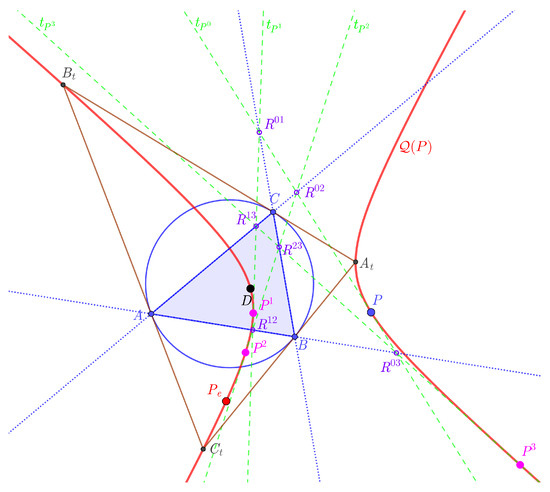

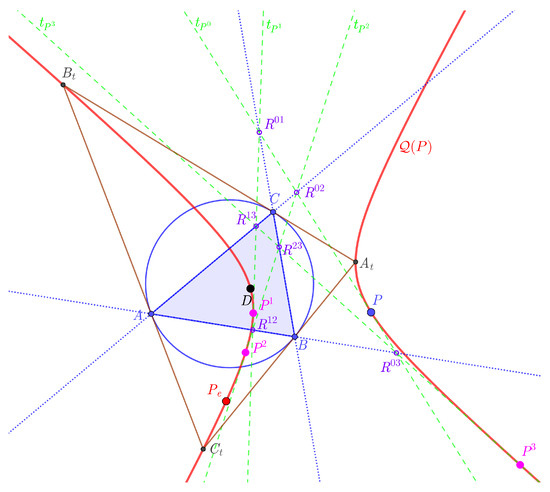

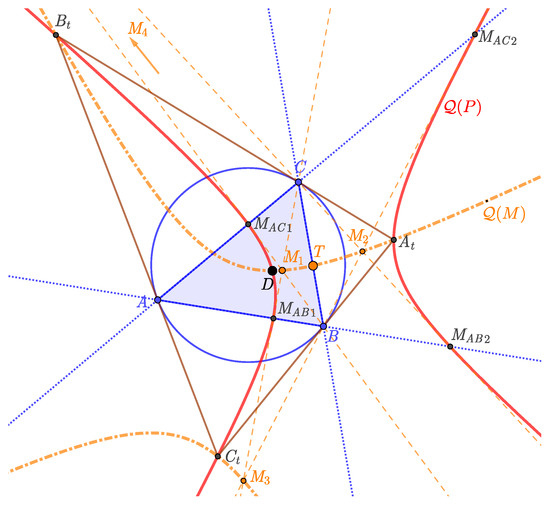

The transformation by which every point P is mapped onto the point by this process is called the Exeter transformation of the plane with respect to the triangle (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Exeter transformation.

The first question naturally arises: are such three lines concurrent and we have a unique point for each P? For verifying our statements, we use an analytical way with barycentric coordinates.

Let be the fundamental non-degenerate triangle with sidelengths , , , where the barycentric coordinates of A, B and C are , , and , respectively. Let the angle C be its largest (not smaller than the others) angle. Let be the circumcircle of with equation

and let the triangle be the tangential triangle of . Now, the sides of are on the tangent lines to at the vertices of . Thus, if is an acute triangle, then the incircle of coincides with (the triangle is known as the Gergonne triangle of ). If is an obtuse triangle, then is one of the excircles of . If is right angled, then is an ideal point. In all cases, the segment touches the circle at point C. In the projective sense, the lines of the sides of divide the plane into four subsets. One is bounded, the others are unbounded in the affine sense. Let denote the subset which contains .

The homogeneous barycentric coordinates of the vertices of are

Points , and are also known as exsymmedian points with respect to . As usual, we denote the homogeneous barycentric coordinates by and the normalized (or absolute) barycentric coordinates by .

We consider an arbitrary point in the plane of triangle

where , , and , so at least two coordinates are not zero (, or ). Let the lines , , and meet at , , and , respectively.

Lemma 1.

The lines , and from Definition 2 are concurrent for all arbitrary point P.

Proof.

The equation of the line is . Similarly, the equations of lines and are and , respectively. Their intersection points with the circumcircle are , , and .

The equation of line is . Similarly, the equations of lines and are and , respectively. We then have from their coefficients that

which implies the concurrency. □

Let the point of concurrence of lines , , and be (Figure 2). The image of a point P under the Exeter transformation with respect to triangle is the point . We denote it by . Let be the centroid of ( in [1]). Then is the Exeter point ( in [1]) of triangle . That is why we call this transformation the Exeter transformation.

In the following, we examine the Exeter transformation and give some of its properties:

Theorem 1.

The barycentric coordinates of , which is the image of (, , ) over the Exeter transformation with respect to the triangle , are

where , and .

Proof.

As the lines , , and are concurrent according to Lemma 1, in order to determine the intersection point of lines , we solve the system of their equations, and we obtain the concurrence point with barycentric coordinates (2). □

Remark 1.

If (P is not on any sideline of ), then from (2) we have

Remark 2.

If a triangle is equilateral, so , then the barycentric coordinates of are , and if , then the normalized barycentric coordinates of are

where

If we used the planar by projective coordinates (obtained from a projective base given by the points where , and C are triangle vertices and the centroid G is the “unit” point), instead of the barycentric with respect to the triangle , we would notice that the projective coordinates are the same as barycentric in case , but this way we would lose the Euclidean metrical properties of the Exeter transformation. However, we could extend Theorem 1 to the projective plane. Thus, the Exeter transformation works if we consider any circumconic of a triangle A, B, C and its tangential triangle .

Corollary 1.

The range of the Exeter transformation is .

Proof.

We have to prove that is in . For this, we project the point from the vertices of to the sidelines of , namely, from the vertices , and to the sidelines of . We show that these projected points are on the sides of .

For example, the barycentric coordinates of each point of the line are , where the parameter . If , then we have or , and in the case of the point coincides with C, which is one of the points of the circle . Thus, the parameters describe one of the segments , which is the side of . Now, we consider the equation of the line (in the proof of Lemma 1, it is the line ) and substitute into the equation. After a short calculation, we express , where . With similar calculation, we can prove that the other two projected points are on the sides of as well. □

Corollary 2.

If and , then , because (2) contains only even powers of the coordinates of P (recall ). Thus, generally, there are four points which have the same image with respect to the Exeter transformation. Let , , , and .

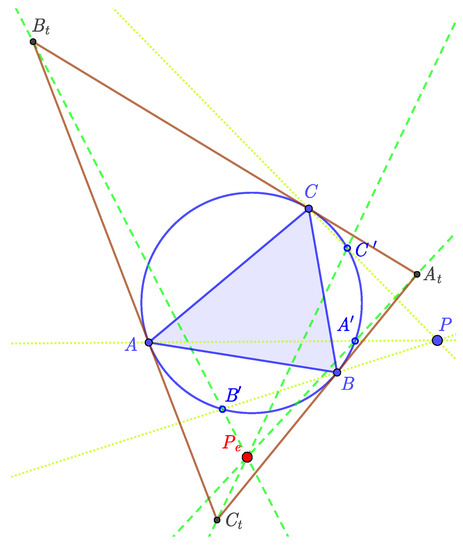

Figure 3 shows the constructions of points . For example, line intersects in point as well, and the intersection point of lines and is . Follow the construction of the image of with respect to the Exeter transformation, then the result is . Similarly, using and we obtain points and .

Figure 3.

Four points (P, , , and ) have the same image .

Corollary 3.

If we consider the centroid of and the vertices of the anticomplementary triangle of with coordinates , , and , respectively, then their common image is the point , which is the Exeter point () of .

Theorem 2.

The Exeter transformations of the lines , , and (except points A, B, C) are the points , and , respectively.

Proof.

The equation of line is , so if P is on line then the coordinates are . Therefore, from (2), as , we have , where . The proof is similar for the other lines. □

Corollary 4.

If P is on one of the lines , or , then some points from among for coincide.

Corollary 5.

If P, , , and are not on lines , , or , then they form a complete quadrangle with diagonal points A, B, and C.

Theorem 3.

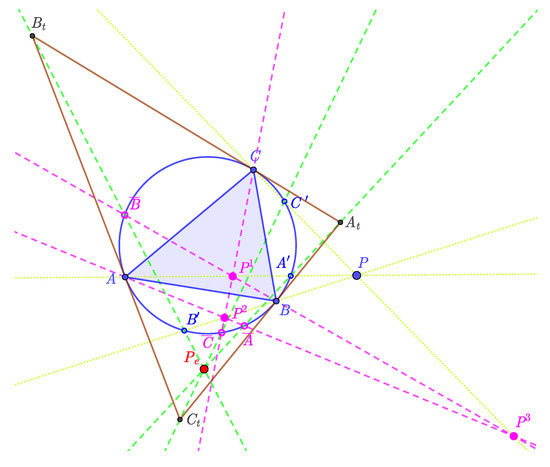

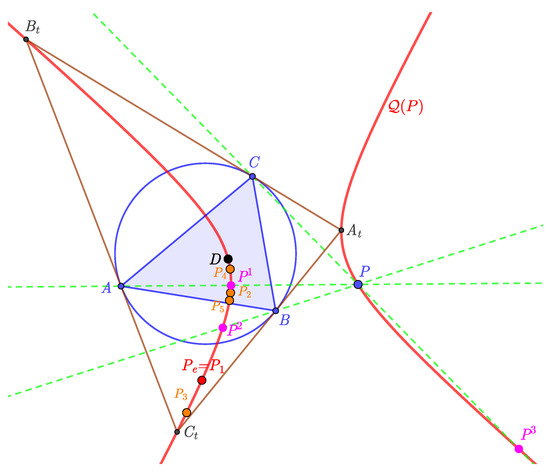

The Exeter transformation of a line passing through neither points A, B, and C is a fourth-order curve incident with points , , and .

Proof.

Without lost of generalization to give a general line g we take the points , and on lines , and , respectively, with baricentric coordinates , and , where and (Figure 4). As then , , and are collinear if and only if . Now, the equation of the line g given by the points , , and is, ex., Because the point , is incident with g, then the parametric system of equations of the line g with parameter t can be considered as , , , and the coordinates of the Exeter transformation of the point T give the parametric system of equations of the Exeter transformation of the line g. Thus, using for T the Equation (2) of the Exeter transformation, we have

where , , and . As the degree of the polynomial in variable t is four ( and are second degree polynomials), then all coordinates of are polynomials in t having degree four. Thus, with points , where is a fourth-order curve. Moreover, according to Theorem 2 the images of , and are , , and , respectively (Figure 4). □

Figure 4.

Exeter transformation of the line g.

2.1. Invariant Elements

Let D be the symmedian point of ( in [1]). (The point of concurrence of lines , and . Thus, is perspective with at the point D. Furthermore, if is acute, then D is the Gergonne point of , the point in [1].) It is well known that

Theorem 4.

D is a fixed point of the Exeter transformation with respect to triangle ; moreover, .

Proof.

It follows directly from Corollary 2. □

Theorem 5.

The lines , , and are invariant lines with respect to the Exeter transformations. Their images are parts of . Moreover, if is acute, then the Exeter transformations of lines , , and are the segments , , and , respectively.

Proof.

For example, let P be on the line . As lines and are the same, then and are on that line. Analytically, the equation of line is and the coordinates of its arbitrary point P is , and its image with respect to (2) is , which is also on line .

The proof is similar for the case of the other lines. □

Theorem 6.

The circumcircle of triangle is fixed (all of its points are fixed, except A, B, and C) over the Exeter transformation, so .

Proof.

The barycentric equation of is . If is a point of , then from we have

Using (2) we obtain . Recall , thus . □

The points , , , and D determine a pencil of conic . Let denote the element of the pencil on which the point P lies. If is acute, then D is inside of the triangle , and the conics of the pencil are hyperbolas.

Theorem 7.

The point and its image under the Exeter transformation with respect to triangle lie on the same conic of the pencil , so , and the equation of is

where

and are the barycentric coordinates of P.

Proof.

The equation of a conic is

Remark 3.

If P is not on any sideline of , so , then the conic is non-degenerate.

Corollary 6.

All conics (or degenerate conics-crossing lines at points A, B, or C) lying through the points , , and D are invariant. Furthermore, their fixed points are D and the intersection points with the circumcircle of .

Corollary 7.

The images of lines , , and are parts of the lines , , and , respectively. Moreover, in the case of an acute they are the segments , , and , respectively.

Theorem 8.

The image of the pencil of a line through A is a pencil of a line through and the corresponding lines intersect each other at the points of .

Proof.

It is a simple corollary of the definition of the Exeter transformation. □

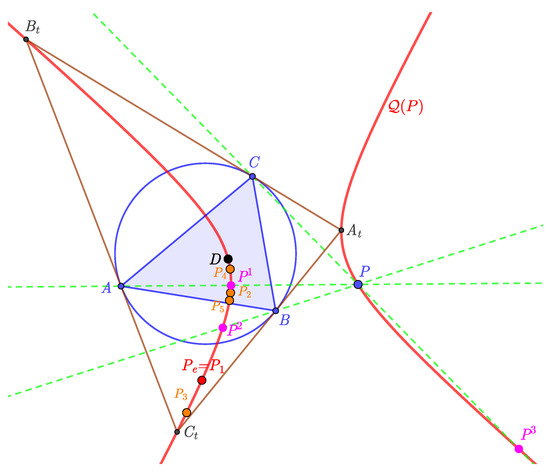

Let the point sequence () be the ith image of P. Thus, and .

Corollary 8.

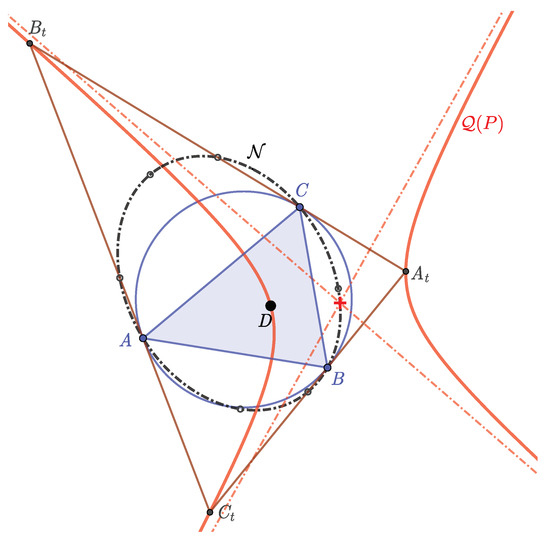

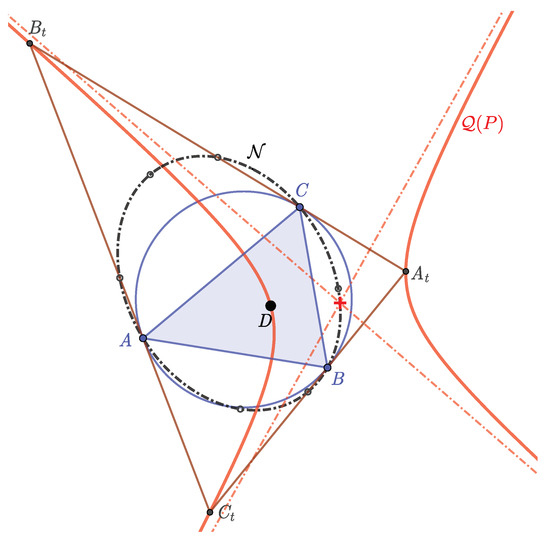

All elements of the point sequence () are on the same conic (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Points on conic .

Proof.

Every conic is clearly defined by five points. The conic is given by , , , D, and . From Theorem 7, we have that the point , the image of the point under the Exeter transformation, lies on the conic . Thus, , , , D, and also define . Recursively—using Theorem 7—we can prove that the point (and so ) lies on the conic as well. □

From Theorem 7 and Corollaries 2 and 8 we gain

Corollary 9.

The points , , and are on the same conic .

Proof.

If and , , then not only P satisfies the Equation (4) of the conic , but also each does. □

Corollary 10.

, , (See Figure 5).

Proof.

From Corollary 9, we know that, for example, the points and are on the same conic . The point lies on the line with the equation . Thus, they are concurrent. As a line has maximum two intersection points with a non-degenerate conic, the other intersection point of the line with must be . □

Corollary 11.

The vertices of any complete quadrangle with diagonal points A, B, and C are on the same conic .

Proof.

According to Corollary 10 and Corollary 5 we know that , lie on the same conic and (clearly) define a complete quadrangle with diagonal points A, B and C. Moreover, it is also well known that a complete quadrangle is clearly defined by three diagonal points and a vertex, i.e., A, B, C, and any point P, where P does not lie on the sidelines of the triangle . The corollary summarizes these statements. □

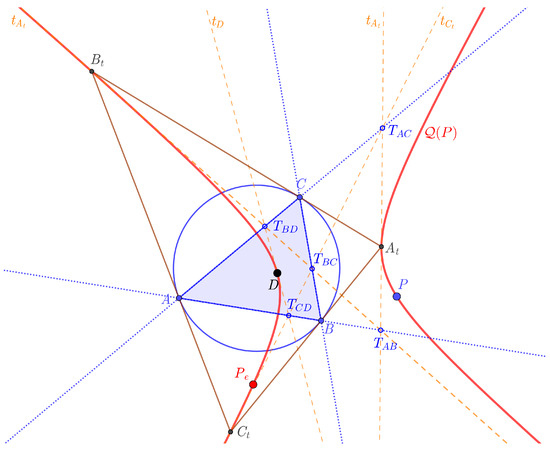

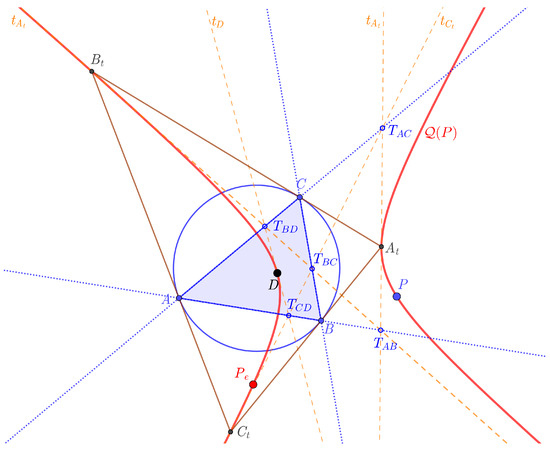

2.2. Tangent Lines

Let be a non-degenerate conic of the pencil . Let us denote by the tangent line to at a point .

Theorem 9.

If the points , are mapped onto the same point by the Exeter transformation with respect to triangle , then the intersection points of the tangent lines , , , and are on the lines of the sides of triangle .

Proof.

Let us consider an arbitrary line with barycentric equation . If it is passing through the point , then . Moreover, the equation of the pencil of lines at is

where q and r are the barycentric coordinates of the lines from the pencil. To derive the tangent line among them, we consider the system of Equations (4) and (7). If its discriminant is zero and we put , then using (5) we have Finally, the equation of is

Similarly, the equations of the pencil of lines at , and , respectively, are , and . Moreover, the equations of lines , , and , respectively, are , and .

Let the point be the intersection of and . From the equations of lines we have that , which is on the line (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Tangent lines at points .

The proof is similar in the case of the other intersection points. Moreover, the intersection points are , , , , and . □

Remark 4.

The points and A, B, and C define a complete quadrilateral with diagonal points and projective harmonic conjugate point pairs with respect to the diagonal points. For example, in Figure 6, the points , , , and form a complete quadrilateral with diagonal points A, , ; B which is the projective harmonic conjugate of A with respect to and ; and C is the projective harmonic conjugate of A with respect to and . Their cross-ratio is .

Corollary 12.

The intersection of any two lines , , , and are on one of the sidelines of triangle .

Proof.

Considering Theorem 4, we obtain the statement from Theorem 9 (see Figure 7). Moreover, the equations of , , , and , respectively, are , , , and . Their intersection points are , , , , , . □

Figure 7.

Tangent lines at points , , , and D.

Let and be the intersection points of line and the non-degenerate . Let us define similarly the points , , , and . Their coordinates from Equation (4) are , , , , , and . (Recall .) Naturally, does not intersect the lines of the sides of at the same time, for example, could not be positive and negative at the same time. Thus, at most four points exist at the same time among the above points. See Figure 8, when intersects the lines and , so , and then .

Figure 8.

Tangent lines at intersection points.

Theorem 10.

The tangent lines to at points and are passing through the point C. Similarly, the tangent lines to at points , or , are passing through the points B or A, respectively.

Proof.

The equations of the tangent lines at points and are and , respectively. Point C coincides with them. □

Let , , , and be the intersection points different from A, B, and C of the tangent lines at , , , , , and .

Theorem 11.

The points , , and are on the same conic with one of the equations

when does not intersect lines , , or , respectively.

Proof.

Theorem 12.

The Exeter transformations of , , , and are the same point T lying on one of the lines of . Moreover, T coincides with , , or , when does not intersect the lines , , or , respectively.

Proof.

We use Corollaries 2 and 5. Analytically, for example, in case of Figure 8, . □

Let be the nine-point conic determined by points , , , and D [10]. Conic is passing through the points A, B, C, and the midpoints of all segments of points , , , and D. Moreover, it also well known that the center of a conic passing through points , , , and D is on the nine-point conic [10]. This proves the following theorem.

Theorem 13.

The center of the conic is lying on the conic (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Nine-point conic.

With a short calculation, we have for the equation of and the coordinates of the center of are

3. Conclusions

With the help of the barycentric coordinates, we showed that the extension of the well-known process of the Exeter point from the centroid of a given triangle provides a so-called Exeter transformation for the whole plane. Each point P, its image , the symmedian, and three exsymmedian points of the triangle are on the same conic . Moreover, three other points (, , and ) of this conic have the common image point as well. The Exeter transformation is nonlinear, as the image of a general line is a fourth-order curve passing through the exsymmedian points of the triangle. We presented the images of some special lines, points, and we determined the invariant points and lines of the Exeter transformation. We particularly examined the intersection points of the tangent lines of the conic at some special points. We think that this nonlinear transformation will reveal several interesting and useful properties during future investigations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.C. and L.N.; Funding acquisition, P.C.; Investigation, P.C. and L.N.; Methodology, P.C. and L.N.; Software, P.C. and L.N.; Visualization, P.C. and L.N.; Writing—original draft, P.C. and L.N.; Writing—review and editing, P.C. and L.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by VEGA grant (Vedecká Grantová Agentúra MŠVVaŠ SR) number 1/0386/21.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kimberling, C. Encyclopedia of Triangle Centers. Available online: http://faculty.evansville.edu/ck6/encyclopedia/ETC.html (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Minevich, I.; Morton, P. Synthetic foundations of cevian geometry, IV: The TCC-Perspector Theorem. Int. J. Geom. 2017, 6, 61–85. [Google Scholar]

- Grozdev, S.; Okumura, H.; Dekov, D. Incentral triangle. Comput. Discov. Math. 2017, 2, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Grozdev, S.; Okumura, H.; Dekov, D. Notable circles. Comput. Discov. Math. 2017, 2, 117–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kimberling, C. Exeter Point. Available online: https://faculty.evansville.edu/ck6/tcenters/recent/exeter.html (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Scott, J.A. The Exeter point revisited. Math. Gaz. 2012, 96, 160–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitan, F.J.G. Barycentric Coordinates. Int. J. Comput. Discov. Math. 2015, 0, 32–48. Available online: https://www.journal-1.eu/2015/01/Francisco-Javier-Barycentric-Coordinates-pp.32-48.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Volenec, V. Metrical relations in barycentric coordinates. Math. Commun. 2003, 8, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Volenec, V. Circles in barycentric coordinates. Math. Commun. 2004, 9, 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, D. Thales and the nine-point conic. Morgan Gaz. 2016, 8, 27–78. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).