Abstract

Gini covariance plays a vital role in analyzing the relationship between random variables with heavy-tailed distributions. In this papaer, with the existence of a finite second moment, we establish the Gini–Yule–Walker equation to estimate the transition matrix of high-dimensional periodic vector autoregressive (PVAR) processes, the asymptotic results of estimators have been established. We apply this method to study the Granger causality of the heavy-tailed PVAR process, and the results show that the robust transfer matrix estimation induces sign consistency in the value of Granger causality. Effectiveness of the proposed method is verified by both synthetic and real data.

1. Introduction

The heavy-tailed distribution is graphically thicker in the tails and sharper in the peaks than the normal distribution. Intuitively, this means that the probability of extreme values is greater for these data than for normally distributed data. The heavy-tailed phenomenon has been encountered empirically in various fields: physics, earth sciences, economics and political science, etc. Periodicity is a wave-like or oscillatory movement around a long-term trend presented in a time series. It is well-known that cyclicality caused by business and economic activities is usually different from trend movements, not in a single direction of continuous movement, but in alternating fluctuations between ups and downs. When these components, trend and cyclicality, do not evolve independently, traditional differencing filters may not be suitable (see for example, Franses and Paap [1], Bell et al. [2], Aliat and Hamdi [3]). Periodic time series models are used to model periodically stationary time series. Periodic vector autoregressive (PVAR) models extend the classical vector autoregressive (VAR) models by allowing the parameters to vary with the cyclicality.

For fixed v and predetermined value T, the random vector represents the realization during the vth season, with , at year . The PVAR model order at season v is given by , whereas , represent the PVAR model coefficients during season v. The error process corresponds to a periodic white noise, with and , where is a zero vector of order d and is a unit matrix of order d.

This paper seeks to establish a PVAR model to simulate the heavy-tailed time series. Let random vectors be from a stationary stochastic process , where the transpose (indicated by ⊤) of a row vector is a column vector.

We consider first-order PVAR model,

where , T is the period of , denotes the latent heavy-tailed innovation, and A is the transition matrix. In this paper, we assume that the entries of the heavy-tailed innovation obey a power-law distribution with and , then the second moment is finite and the third moment is infinite. From the Equation (2) we know that, given k, the vector follows a first-order vector autoregressive (VAR). We call the first-order PVAR process stable if all eigenvalues of transition matrix A have modulus less than 1, the condition is equivalent to for all (see for example, Section 2.1 in Lütkepohl [4]). The transition matrix characterizes the temporal dependence for sequence data, and plays a fundamental role in forecasting. Moreover, the zero and nonzero entries of the transition matrix is often closely related to Granger causality. This manuscript focuses on estimating the transition matrix of high-dimensional heavy-tailed PVAR processes.

PVAR models have been extensively studied under the Gaussian assumption, the Gaussian PVAR models assume that the latent innovations are independent identity distribution Gaussian random vectors. Under this model, there are two kinds of methods to estimate the transition matrix under high dimensional setting, one is the Lasso-based estimation procedures, see [5,6,7,8], and the other is Dantzig-selector-type estimators, see [9,10,11,12]. Under the non-Gaussian VAR process, Qiu et al. [13] proposed a quantile-based dantzig-selector-type estimator of the transition matrix for elliptical VAR process. Wong et al. [14] provided an alternative proof of the consistency of the Lasso for sparse non-Gaussian VAR models. Maleki et al. [15] extended the multivariate setting of autoregressive process, by considering the multivariate scale mixture of skew-normal distributions for VAR innovations.

The statistical second-order information contained in the data is usually expressed by the variance and covariance, most of the literature dealing with time series measure dependence using the variance and covariance. To investigate the validity of the variance estimates, we need the presence of the fourth order moment of the random variables. For the heavy-tailed nature of financial data, the third-order moments of random variables are usually non-existent. Schechtman and Yitzhaki [16] proposed the concept of Gini covariance, which has been used widely to measure the dependence of heavy-tailed distributions. Let H be the joint distribution of the random variables X and Y with the marginal distribution functions and , respectively. The standard Gini covariance is defined as

assuming the random variables with only a finite first moment. The Gini covariance has an advantage when analyzing bivariate data defined by both variate values and ranks of the values. The representation of Gini covariance indicates that it has mixed properties of the variable X and the rank of the variable Y, and thus complements the usual covariance and rank covariance [16,17,18]. In terms of balance between effciency and robustness, Gini covariance plays an important role in measuring association for variables from heavy-tailed distributions [19].

The Yule–Walker equations arise naturally in the problem of linear prediction of any zero-mean weakly stationary process based on a finite number of contiguous observations. The Yule–Walker equations provide a straightforward connection between the autoregressive model parameters and the covariance function of the process. In this paper, relaxing the strong assumption of the existence of higher order moments of the regressors, we use a non-parametric method to estimate the Gini covariance matrix, establish the Gini–Yule–Walker equation to estimate the sparse transition matrix of stationary PVAR processes. The estimator falls into the category of Dantzig-selector-type estimators. With existence of a finite second moment, we investigate the asymptotic behavior of the estimator in high dimensions.

The paper is orginazed as follows: In Section 2, we establish the Gini–Yule–Walker equation and estimate the sample Gini covariance matrix. In Section 3, we derive the convergence rate of transfer matrix estimation. In Section 4, we discuss the characterization and estimation of Granger causality under the heavy-tailed PVAR model. In Section 5, both synthetic and real data are used to demonstrate the empirical performance of the proposed methodology.

2. Model

In this section, the notations are set. Then, we establish the Gini–Yule–Walker equation, obtain simple non-parametric estimators for Gini covariance matrix and investigate the convergence rate of the sample Gini covariance matrix.

2.1. Notation

Let be a d-dimensional real vector, and be a matrix. For , we define the vector norm of v as , and the vector norm of v as . Let the matrix norm of M as , the matrix norm , and be two random vectors.

2.2. Gini–Yule–Walker Equation

In this paper, we model the time series vector by a stationary PVAR process under the existence of second moment. For each , follow a lag-one VAR process, with independent of , and .

We define

this VAR process may be performed by concatenating the equation systems to analyze the following equation,

where , and

the ⊗ is a Kronecker product operator.

Since the matrix is a block diagonal matrix, the estimation problem can be decomposed into d independent sub-problems. Let us consider the i-th equation of the system.

the above equation system can be considered as a multiple regression

this equation system can be abbreviated as

with samples to estimate the i-th line of transition matrix A.

Let be the distribution of , we assume the independence between and , for . Then we get the Gini covariance matrix equation issue from Equation (5),

From the above equation, we obtain the so called Gini–Yule–Walker Equation

where , . The entries of are given by , and the entries of are given by .

2.3. Sample Gini Covariance Matrix

We use a statistic method to estimate the Gini covariance matrix and . From Equation (6), the elements of the covariance matrix and can be divided into two categories: Gini covariance and Gini mean difference , with .

For the Gini covariance , we have sample space

The i-th ordered variable of is expressed by and the associated variable of (matched with ) is expressed by , which is the concomitant of the i-th order statistic. In this set-up, in the context of non-parametric estimation of a regression function, Yang [20] proposed a statistic of the form

where is a bounded smooth function, is a real valued function of and is the empirical distribution function corresponding to . The Gini covariance defined in Equation (3) can be rewritten as

Choosing and from Equation (7), we obtain an estimator of as

For the Gini mean difference , we have sample space . Let and be two independent random variables with distribution function , the Gini mean difference can be expressed as

The estimator of based on U-statistics is given by

where . After some simplification, we obtain

where is the i -th order statistic based on the sample space .

2.4. Convergence Rates of the Estimator and

In this subsection, with the truncation method, we use the Bernstein’s inequality to investigate the convergence rates of the estimator and . From Equations (8) and (9), we define , and , where is the variance of the variable .

For analysis, we require the following three assumptions on the time series and the size of variables :

Assumption A1.

From Equation (2), suppose that the entries of the heavy-tailed innovation obey a power-law distribution with and , then the second moment is finite and the third moment is infinite.

Assumption A2.

Suppose that , , c is a finite constant, for .

Assumption A3.

Suppose , for

Lemma 1.

Let be a stationary PVAR process from Equation (2), and be a sequence of observations from . Suppose that Assumptions (A1)–(A2) are satisfied. Then, for T and n large enough, with probability no smaller than we have

Proof.

Assuming that m and are constants greater than 0, and

Then, is a bounded random variable and satisfies the property of independent identical distribution, it follows from the Bernstein’s inequality that

where .

Let and , we have

As and , assuming and , then .

With similar proof methods, we obtain that

This completes the proof. □

From Equations (5) and (6), we define the sample estimation of Gini covariance matrix G as and the sample estimation of Gini covariance matrix as , .

Next, we investigate the convergence rates of the estimator and under the norm.

Lemma 2.

Let be a stationary PVAR process from Equation (2), and be a sequence of observations from . Suppose that Assumptions (A1)–(A3) are satisfied. Then, for T and n large enough, with probability no smaller than we have

3. Theoretical Properties

The above optimization problem can be further decomposed into d subproblems. The i-th row of transition matrix A by

Compared to the lasso-type procedures, the proposed method can be solved in parallel and Equation (17) can be solved efficiency using the parametric simplex method for sparse learning in [21].

Based on Lemma 2, we can further deliver the rates of convergence of under the matrix norm and norm. We start with some additional notation. For and that may scale with d, we define the matrix class

requires the transition matrices are sparse in rows. If , then the maximum number of nonzeros in rows of transition matrice is at most . is also investigated in [12].

Theorem 1.

Let be a stationary PVAR process from Equation (2). Suppose that Assumptions (A1)–(A3) are satisfied. The transition matrix , if we choose the tuning parameter . Then, for T and n large enough, with probability no small than , we have

Proof.

We first show that with large probability, A is feasible to the optimization problem. By the Gini–Yule–Walker equation, we have

The last inequality is due to , by Lemma 2, with probability no small than that,

A is feasible in the optimization equation, by checking the Equation (17), we have with probability no smaller than .

Next, we prove Equation (20). Let , we have

with probability no smaller than .

Let and . Define

Then, we have

Suppose and setting we have

Therefore, we have

Since the above equation holds for any , we complete the proof.

□

4. Granger Causality

In this section, the practical example is conducted to verify the effectiveness of the proposed methods, moreover, the characterization and estimation of Granger causality under the heavy-tailed PVAR model are discussed. Firstly, we give the definition of Granger causality.

Definition 1.(Granger [22]) Let be a stationary process, where . For Granger causes if and only if there exists a measurable set A such that

for all where is the subvector obtained by removing from

For a Gaussian VAR process we have that Granger causes if and only if the entry of the transition matrix is non-zero [4]. For the heavy-tailed PVAR process, let be a stationary PVAR process from Equation (2), we define

In the next theorem, we show that a similar property holds for the heavy-tailed PVAR process.

Theorem 2.

Let be a stationary PVAR process from Equation (2). Suppose that Assumptions (A1)–(A3) are satisfied, and for any Then, for we have

- 1.

- If then Granger causes .

- 2.

- If we further assume that is independent of for any we have that Granger causes if and only if .

Proof.

In order to prove Issue we only need to prove that doesn’t Granger cause implies Suppose for some we have

for any measurable set A. The above equation implies that conditioning on , is independent of Hence, we have

Plugging into the above equation, we have

The second term on the right hand side is since given is constant. Since and are independent for any , we have for any . Using Theorem 2.18 in Fang et al. [23], we have the third term is also Thus, we have and hence This proves Issue 1.

Given Issue to prove Issue it remains to prove that implies that doesn’t Granger cause Since we have

Here p is the conditional probability density function. The last equation is because is independent of and the fact that is constant given Hence, we have

and thus

□

Remark 1.

The assumption that requires that cannot be perfectly predictable from the past or from the other observed random variables at time t. Otherwise, we can simply remove from the process since predicting is trivial. Assuming that is independent of for any the Granger causality relations among the processes is characterized by the non-zero entries of To estimate the Granger causality relations, we define where

for some threshold parameter γ. To evaluate the consistency between and A regarding sparsity pattern, we define function . For a matrix M, define . The next theorem gives the rate of γ such that recovers the sparsity pattern of A with high probability.

Theorem 3.

Let be a stationary PVAR process from Equation (2). Suppose that Assumptions 1–3 are satisfied. The transition matrix , if we set

then, with probability no smaller than , we have provided that

Proof.

The proof is a consequence of Theorem 1. In detail, if by Equation (25), we have By Theorem 1, with probability no smaller than , we have . Thus, we have with probability no smaller than . By the definition of A, we have .

If by Equation (25), we have Using Theorem 1, we have with probability no smaller than , By the definition of we have .

If , using Theorem 1, we have with probability no smaller than , since 0. By the definition of we have .

□

5. Experiments

This section provides some numerical results on synthetic and real data. We consider Lasso and Dantzig selector for comparison.

- Lasso: an regularized estimator defined aswhere , .

- Dantzig selector: the estimator proposed in [12],and be the marginal and lag one sample covariance matrices of Equation (2).

- G-Dantzig selector: the estimator described in Equation (17).

5.1. Synthetic Data

In this subsection, we compare the performance of our method with the lasso and Dantzig under synthetic data. The “flare” package in R is used to create the transition matrix according to three patterns: cluster, hub, random. We rescale A such that , generate such that , then calculate the covariance matrix of the noise vector as . Let the periodical time series length , the period length and the dimension , with and , we simulate periodical time series according to the model described in Equation (2). Specifically, we consider three models:

- Model 1: Data generated from Equation (2), where the errors . There is no outliers under Model 1.

- Model 2: Data generated from Equation (2), where the errors . No outliers appear and the tail of the error distribution is heavier than that of the normal distribution.

- Model 3: Data generated from Equation (2) with the same error distribution as Model 1. Then replace by for , where and are independently generated from distribution, there are outliers that deviate from the majority of the observations.

The tuning parameter is chosen by cross validation. We construct 20,000 replicates and compare the three methods described above. Table 1 presents averaged estimation errors under three matrix norms. From this table, we have the following findings: Under the Gaussian model (Model 1), G-Dantzig selector has comparable performance as Dantzig selector and out performs Lasso. Under Model 2 and 3, our methods are more stable than Lasso and Dantzig selector. Thus, we conclude that the G-Dantzig selector is robust to the heavy-tailedness of data and the possible presence of outliers.

Table 1.

Comparison of estimation errors of three methods under different setups. The standard deviations are shown in parentheses. Here , , are the , and Frobenius matrix norms respectively.

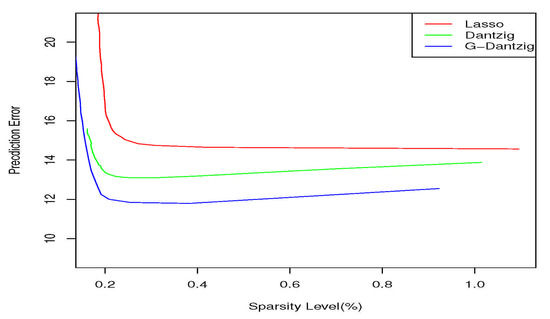

Figure 1 plots the prediction errors against sparsity for the three transition matrix estimators. We observe that G-Dantzig selector achieves smaller prediction errors compared to Lasso and Dantzig selector.

Figure 1.

Prediction errors in stock prices plotted against the sparsity of the estimated transition matrix.

5.2. Real Data

We further compared the three methods on a real equity data from Yahoo Finance. We collected the 10-minutes time intervals price in Monday of each week for 50 stocks with the highest volatility that were consistently in the 500 index from 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2020. Then, the periodical time series length was , the period length was and the dimension was . Since we chose the data points on the Monday of each week, the data points can be seen as independent of each other. Estimations of the transition matrix were obtained by the Lasso, Dantzig selector and G-Dantzig selector, where is the fraction of non-zero entries of and can be controled by the tuning parameters and . We define the prediction error associated with to be

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we developed a Gini–Yule–Walker equation for modeling and estimating the heavy-tailedness data and the possible presence of outliers in high dimensions. Our contributions are three-fold. (i) At the model level, we generalized the Gaussian process to time series with the existence of merely second order moments. (ii) Methodologically, we proposed a Gini–Yule–Walker-based estimator of the transition matrix. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed estimator is robust to heavy-tailedness of data and the possible presence of outliers. (iii) Theoretically, we proved that the adopted method yields a parametric convergence rate in the matrix norm. In this manuscript, we focused on the stationary vector autoregressive model and our method is designed for such stationary process. The stationary requirement is a common assumption in analysis and is adopted by most recent works, for example, see and [14,24]. We notice that there are works in handling time-varying PVAR models, checking for example in [25]. We would like to explore this problem in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z. and D.H.; methodology, D.H. and J.Z.; software, J.Z.; validation, J.Z.; formal analysis, J.Z.; investigation, J.Z.; resources, J.Z.; data curation, J.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z.; writing—review and editing, J.Z.; visualization, J.Z.; supervision, J.Z. and D.H.; project administration, J.Z.; funding acquisition, D.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundations of China [grant number 11531001].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Franses, P.H.; Paap, R. Periodic Time Series Models; Oxford U Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, W.R.; Holan, S.H.; McElroy, T.S. Economic Time Series: Modeling and Seasonality; Chapman and Hall/CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Aliat, B.; Hamdi, F. On Markov-switching periodic ARMA models. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods. 2018, 47, 344–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lütkepohl, H. New Introduction to Multiple Time Series Analysis; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, C.; Davis, R.A.; Pipiras, V. Sparse seasonal and periodic vector autoregressive modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2017, 106, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Yang, H.; Yang, L. Change points detection and parameter estimation for multivariate time series. Soft Comput. 2020, 24, 6395–6407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Michailidis, G. Regularized estimation in sparse high-dimensional time series models. Ann. Stat. 2015, 43, 1535–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, P.; Safikhani, A.; Michailidis, G. Multiple Change Points Detection in Low Rank and Sparse High Dimensional Vector Autoregressive Models. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2020, 68, 3074–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Liu, H. Transition Matrix Estimation in High Dimensional Vector Autoregressive Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Atlanta, GA, USA, 16–21 June 2013; pp. 172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, D.; Gu, Q.; Whitehouse, K. High-dimensional time series clustering via cross-predictability. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–22 April 2017; pp. 642–651. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Xu, M.; Wu, W.B. Regularized estimation of linear functionals of precision matrices for high-dimensional time series. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2016, 64, 6459–6470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Lu, H.; Liu, H. A Direct Estimation of High Dimensional Stationary Vector Autoregressions. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2015, 16, 3115–3150. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, H.; Xu, S.; Han, F.; Liu, H.; Caffo, B. Robust estimation of transition matrices in high dimensional heavy-tailed vector autoregressive processes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. International Conference on Machine Learning, Lille, France, 7–9 July 2015; pp. 1843–1851. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, K.C.; Li, Z.; Tewari, A. Lasso guarantees for mixing heavy-tailed time series. Ann. Stat. 2020, 48, 1124–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, M.; Wraith, D.; Mahmoudi, M.R.; Contreras-Reyes, J.E. Asymmetric heavy-tailed vector auto-regressive processes with application to financial data. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2020, 90, 324–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schezhtman, E.; Yitzhaki, S. A measure of association based on gin’s mean difference. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 1987, 16, 207–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schechtman, E.; Yitzhaki, S. On the proper bounds of the Gini correlation. Econ. Lett. 1999, 63, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schechtman, E.; Yitzhaki, S. A family of correlation coefficients based on the extended Gini index. J. Econ. Inequal. 2003, 1, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yitzhaki, S.; Schechtman, E. The Gini Methodology: A Primer on a Statistical Methodology; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.S. Linear functions of concomitants of order statistics with application to nonparametric estimation of a regression function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1981, 76, 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Liu, H.; Vanderbei, R. The fastclime package for linear programming and large-scale precision matrix estimation in R. J. Mach. Learn. Res. JMLR 2014, 15, 89–493. [Google Scholar]

- Granger, C.W. Testing for causality: A personal viewpoint. J. Econ. Dyn. Control. 1980, 2, 329–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.W. Symmetric Multivariate and Related Distributions; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S.; Bickel, P.J. Large vector auto regressions. arXiv 2011, arXiv:1106.3915. [Google Scholar]

- Haslbeck, J.M.; Bringmann, L.F.; Waldorp, L.J. A Tutorial on Estimating Time-Varying Vector Autoregressive Models. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2020, 4, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).