Abstract

This paper deals with the extreme value analysis for the triangular arrays which appear when some parameters of the mixture model vary as the number of observations grows. When the mixing parameter is small, it is natural to associate one of the components with “an impurity” (in the case of regularly varying distribution, “heavy-tailed impurity”), which “pollutes” another component. We show that the set of possible limit distributions is much more diverse than in the classical Fisher–Tippett–Gnedenko theorem, and provide the numerical examples showing the efficiency of the proposed model for studying the maximal values of the stock returns.

PACS:

60G70; 60F99

1. Introduction

Consider the mixture model

where is a mixture parameter, and are cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) of two distributions parametrised by vectors correspondingly, and . In this paper we focus on the case when the second component in this mixture corresponds to some heavy-tailed distribution, while the first one can be either light or heavy tailed. When is small, the second component can be referred to as the heavy-tailed impurity (the term “heavy-tailed impurity” is known in the context of percolation theory, see [1]. Here we use it in a more general set-up, following [2]). Some applications of this approach are described by Grabchak and Molchanov (2015) [2]. For instance, in population dynamics, this approach can be used for modelling the migration of species: The distance of migration of most species can be modelled by light-tailed distribution, but there is a small number of species with “very active” behaviour.

It would be worth mentioning that the parameters and may depend on the number of available observations, denoted below by n. For instance, in the aforementioned example from population dynamics, the proportion of “very active” species decays when the total number of species grows. In this context, the distribution of the resulting variable changes with n, and this model can be considered as the infinitesimal triangular array—a collection of real random variables as such that are independent for each n. The classical limit theorems for this class of models are well known in the literature, see, e.g., monographs by Petrov (2012) [3], Meerschaert and Scheffler (2001) [4]. For instance, it is known that the class of possible non-degenerate limit laws of the sums with deterministic and triangular array satisfying the assumption of infinite smallness,

coincides with the class of infinitely divisible distributions.

Surprisingly, there are very few papers dealing with the extreme value analysis for this model. To the best of our knowledge, there exist no general statements describing the class of non-degenerate limits of

with deterministic . Clearly, the convergence to types theorem is applicable to this situation and guarantees that the limit law is determined up to the change of location and scale. Nevertheless, unlike the well-known Fisher–Tippett–Gnedenko theorem, the class of limit distributions in (2) includes not only the Gumbel, Fréchet and max-Weibull laws. Some conditions guaranteeing the convergence of the triangular array to some limit are given by Freitas and Hüsler (2003) [5], but their results essentially employ the assumption that the limit distribution is twice differentiable, which is violated in the examples of the model (1) provided below. Let us mention here that other known papers on this topic are concentrated on some particular examples yielding convergence to the classical extreme value distributions, such as the Gumbel law, and those related to them, see Anderson, Coles and Hüsler (1997) [6], Dkengne, Eckert and Naveau (2016) [7].

In the first part of the paper (Section 2) we consider the particular case of (1), when the first component has the Weibull distribution (and therefore it is in the maximum domain of attraction (MDA) of the Gumbel law), while the heavy-tailed impurity is modelled by the regularly varying distribution (MDA of the Fréchet law). Note that in the classical setting, when the parameters and are fixed, the limit behaviour of the sum is determined by the second component, and therefore the maximum under proper normalisation converges to the Fréchet law. Interestingly enough, even in the case when only one parameter (namely the mixing parameter ) varies, the set of possible limit distributions includes Gumbel and Fréchet distributions and also one discontinuous law. The exact statement is formulated in Theorem 1.

In Section 3 we turn towards a more complicated model, which appears when one uses the truncated regularly varying distribution for the second component, and the truncation level M grows with . This part of our research is motivated by a discussion concerning the choice between truncated and non-truncated Pareto-type distributions, see Beirlant, Fraga Alves and Gomes (2016) [8]. The asymptotic behaviour depends on the rate of growth of M: As we show, the resulting conditions are related to the soft, hard and intermediate truncation regimes introduced by Chakrabarty and Samorodnitsky (2012) [9]. Note that in that paper it is shown that the softly truncated regularly varying distribution has heavy tails (understood in the sense of the non-Gaussian limit law for the sum), and therefore the term “heavy-tailed impurity” can be also used for models of this kind.

The main theoretical contribution of our research is formulated as Theorem 2, dealing with the case when both and M depend on . It turns out that the set of possible limit laws in (2) includes six different distributions, and, for some sets of parameters, the maximal value diverges under any (also nonlinear) normalisation. Our theoretical findings are illustrated by the simulation study (Section 4).

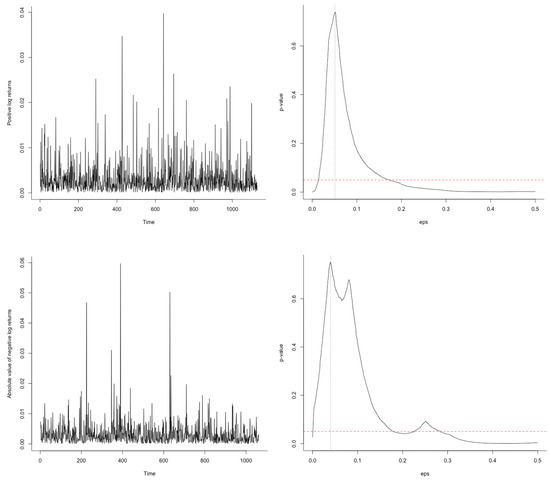

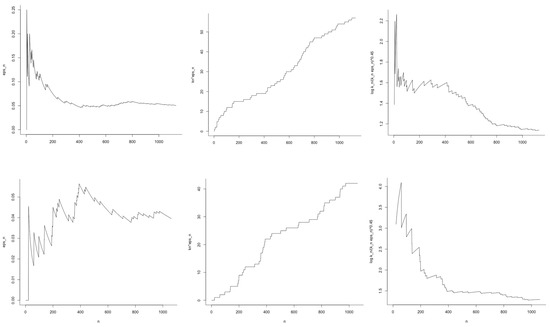

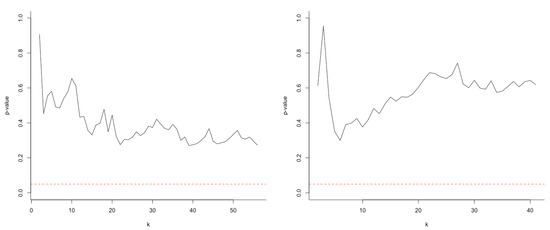

The choice of the Weibull distribution for the first component in (1) is partially based on the great popularity of this distribution in applications, see, e.g., the overview by Laherrere and Sornette (1998) [10]. As we show in Section 5, our model with heavy-tailed impurity is more appropriate for modelling the stock returns as a “pure” model. In this context, our paper continues the discussion started in the paper by Malevergne, Pisarenko and Sornette (2005) [11], where it is shown that the tails of the empirical distribution of log-returns decay slower than the tails of the Weibull distribution but faster than the power law.

2. Weibull-RV Mixture

In this section, we focus on a particular case of the model (1), namely

where , is the distribution function of the Weibull law,

and corresponds to the regularly varying distribution on ,

with and a continuous slowly varying function . Let us recall that by definition,

and the term “slow variation” comes from the property

for every The extensive overview of the properties of slowly varying functions is given in [12,13].

As we already mentioned in the introduction, the first component is in the MDA of the Gumbel law, while the second is in the MDA of the Fréchet law. In Appendix A, we show that the the mixture distribution function F is in the MDA of the Fréchet law, provided that the parameters and are fixed.

In what follows we consider the case when the mixing parameter decays to zero as n grows. It is natural to slightly generalise the model to the form of row-wise independent triangular array

where is an unbounded increasing sequence, and for any n the random variables are independent. The set-up allowing various numbers of elements in different rows is standard both in studying the classical limit laws (see [3]) and in the extreme value theory (see [7]).

As we show in the next theorem, the asymptotic behaviour of the maximum in this model is determined by the rate of growth of , the rate of decay of and the slowly varying function . Note that the rates of and are compared in terms of the following three alternative conditions,

Theorem 1.

Consider the row-wise independent triangular array (7). Assume that (this assumption means that the slowly varying function does not exhibit infinite oscillation. The counterexample to this condition is given in [14], Example 1.1.6). Then for any sequences , there exist deterministic sequences such that

with some non-degenerate limit law More precisely, belongs to the type of the following three distribution functions (due to the convergence to types theorem (Theorem A1.5 from [15]), if is the distribution function of the limit law in (11), then any other non-degenerate law appearing in (11) under another normalisation is of the form with some constants ):

- Gumbel distribution, , , if and only if any of the following conditions is satisfiedIn all cases, possible choice of the normalising sequences is

- Fréchet distribution with parameter α, , , if and only if any of the following conditions is satisfiedIn all cases, one can takewhere for

Proof.

The proof is given in Appendix B. □

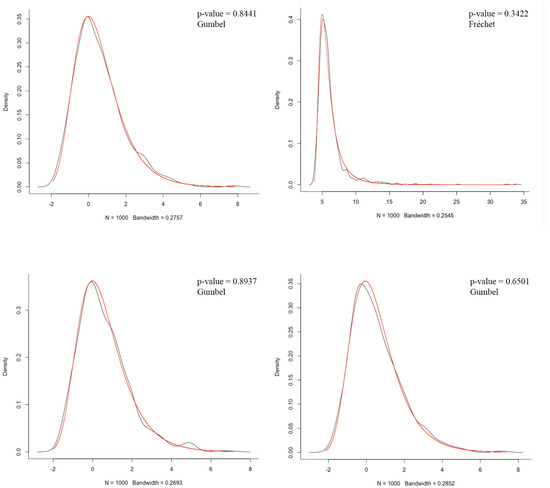

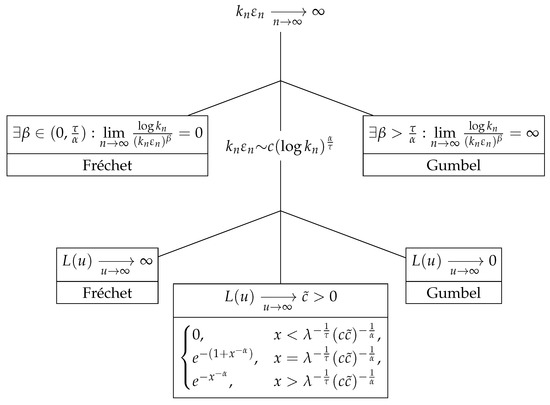

The graphical representation of this result is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Possible limit distributions for maxima of the triangular array (3).

3. Weibull-Truncated RV Mixture

Now we consider one more complicated model, such that the distribution of the second component in (3) also changes as n grows. Consider the mixture distribution

whereas before, , is the distribution function of the Weibull law (see (4)), while is the upper-truncated regularly varying distribution,

with corresponding to a regularly varying distribution (5).

It would be an interesting mentioning that the components in this model correspond to different maximum domains of attraction: the maximum for the first component under proper normalisation converges to the Gumbel law, while the second—to the max-Weibull law, see Appendix C.

By analogy with (7), we consider the triangular array

where are unbounded increasing sequences, and for any n the random variables are independent. Note that the classical limit laws for this model (law of large numbers and limit theorems for the sums) are essentially established in [16].

The next theorem reveals the asymptotic behaviour of the maximal value depending on the rates of , and the properties of the slowly varying function . An important difference from the model considered in Section 2 is that in some cases the limit distribution is degenerate for any (also non-linear) normalising sequence.

It turns out that if tends to any finite constant, then the limit distribution is Gumbel. Our findings in the remaining case are presented in Table 1. The asymptotic behaviour of the maximum is determined by the asymptotic properties of the sequences in terms of (8)–(10), and the rate of growth of in terms of the following three alternating conditions:

Table 1.

Possible limit distributions for maxima of the triangular array (16).

The conditions (17)–(19) are related to the notion of hard and soft truncation. Following [9], we say that that a variable is truncated softly, if

For a regularly varying distribution of , the condition (20) holds if there exists such that . This fact follows from

for any (here and below we mean by that ). Analogously, is truncated hard, that is,

if there exists such that

The paper [9] deals with the asymptotic behaviour of the sums of random variables with truncated regularly varying distributions. It is demonstrated that the behaviour significantly depends on the truncation regime. This research was further extended by Paulauskas [17], who studied the convergence of sums of linear processes with softly and hardly tapered innovations.

Our results for the case (17) (see first raw in Table 1) coincide with the findings from [9]: “In the soft truncation regime, truncated power tails behave, in important respects, as if no truncation took place”. In fact, in our setup, the results are completely the same as for the non-truncated distribution considered in Theorem 1.

Our outcomes for (18) (second raw in Table 1) are quite close to another finding from [9], namely, “in the hard truncation regime much of “heavy tailedness” is lost”. Actually, we get that the behaviour is determined by the first component except the case (9) with .

Finally, the intermediate case (19) (third row in Table 1) is divided into various subcases. The comparison with [9] is not possible because the authors decide to “largely leave” this question “aside in this article, in order to keep its size manageable”. In our research, we provide the complete study of this case.

The exact result is formulated below.

Theorem 2.

Consider the row-wise independent triangular array (16) under the assumption that as Assume also that

Then the non-degenerate limit law for the properly normalised row-wise maximum (see (11)) belongs to the type of the following distributions.

- 1.

- Gumbel distribution, , , if and only if any of the following conditions is satisfied

- 1.1

- as ;

- 1.2

- as , and moreover

In all cases, possible choice of the normalising sequences is given by (12). - 2.

- Fréchet distribution with parameter α, , , if and only if any of the following conditions is satisfiedIn all cases, one can take in the form (13).

- 3.

- Special cases:

In all cases the normalising sequences can be chosen as in (13).

The limit distribution is degenerate for any sequences and in the following three cases:

Moreover, in these cases the distribution of

is degenerate for any increasing sequence which is unbounded in n and

Proof.

The proof is given in Appendix D. □

4. Simulation Study

The aim of the current section is to illustrate the dependence of limit distribution for maxima in the model (16) on the rates of the mixing parameter and of the truncation level . For this purpose we consider four triangular arrays (16) with having all permanent parameters the same, namely, , and . The sequences and are chosen to satisfy the following pairs of conditions: (8)–(17), (9)–(17), (8)–(18) and (9)–(18). The exact form of mixing and truncation parameters are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The values of and chosen for the numerical study.

As previously, the primary separation is made due to the rates of and : We fix and , which imply conditions (8) and (9), respectively. Next, the models are divided according to the rate of growth of in the form with Recall that from Theorem 2, it follows that the limit distribution is Gumbel for the pairs (8)–(17), (8)–(18) and (9)–(18) (note that for the last two cases under our choice), and Fréchet for the pair (9)–(17).

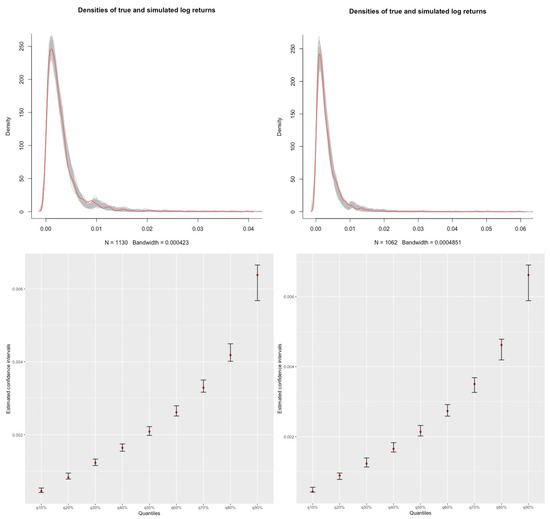

For each case we simulate 1000 samples of length 1000, and find the maximal value of each sample. The goodness-of-fit of the limit distributions of the maximal values suggested by Theorem 2 is tested by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov criterion. Figure 2 depicts the kernel density estimates of the densities of normalised maxima in each case superimposed with the limit distributions implied by Theorem 2. It can be seen that for all groups the density estimates are quite close to the theoretical densities, and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test does not reject the null of the corresponding theoretical distributions (corresponding p-values are given on the same figure).

6. Conclusions

This paper contributes to the existing literature in the following respects.

- We model the heavy-tailed impurity via the mixture distribution with varying parameters and (following the ideas from [8,9]) consider the resulting model as a triangular array. The notion of heavy-tailed impurity is not new, but all previously known probabilistic results are concentrated only on the classical limit laws, see [2,16]. In this paper, we establish the limit laws for the maximum in these models.

- The paper delivers an example of the triangular array such that its row-wise maximum has (under proper normalisation) 6 different distributions, depending on the rates of the varying parameters. To the best of our knowledge, all previous articles on the extreme value analysis for triangular arrays deal with the convergence to the limit law having twice differentiable cdf ([5,7]) or closely related to the classical extreme value distributions ([6]), while some limits in our examples are discontinuous and very different from the classical laws.

- We show the difference between various types of truncation for the regularly varying distributions used for modelling the impurity. Our conditions (17)–(18) are close to soft and hard truncation regimes introduced in [9], leading to similar (but not completely the same) outcomes for our mixture model as for the model considered in [9]. Moreover, unlike previous papers, we study in details the case of intermediate truncation regime (19).

- For practical purposes we describe the four-step scheme for the application of this model to the asset price modelling. This approach can be considered as a possible development of the idea that the distribution of stock returns is in some sense between exponential and power law. A comprehensive discussion of this idea can be found in [11].

Author Contributions

Methodology, E.M. and V.P.; Supervision, V.P.; Visualization, E.M.; Writing—original draft, E.M.; Writing—review & editing, V.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The article was prepared in the framework of a research grant funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (grant ID: 075-15-2020-928).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Classical EVA for the Mixture Model

Let us analyse the asymptotic behaviour of maxima of a sequence of i.i.d. random variables , , with cumulative distribution function (3). That is, we consider

where is some non-decreasing normalising sequence unbounded in n and x. Since are independent,

Since as , , and therefore

Thus, the limit distribution for maxima is determined by the second component, leading to the Fréchet limit. In fact, choosing

we get

that is the Fréchet-type distribution.

Appendix B. Proof of Theorem 1

For given sequences , the left-hand side of (11) can be represented as

where . Our aim is to find the sequences guaranteeing that this limit (denoted by ) is non-degenerate. We divide the range of possible rates of convergence of into several essentially different cases.

- (i)

- Let . As as by the slow variation of (see (6)), we getand therefore we deal with the extreme value analysis of the Weibull law. Since is a von Mises function, i.e., can be represented aswith and , we get that the limit distribution is Gumbel under the choice with

- (ii)

- Let as . This case is divided into several subcases, depending on the relation between and

- First, let us consider . Thenas . Therefore,as for all fixed as . Clearly, since is not present in the above limit, one can take . As for , we havei.e., We haveand therefore the limit distribution in (A1) is non-degenerate (and is actually the Fréchet distribution) if and only ifIt would be a worth mentioning that depends on the function L via the equality (A2). Let us recall that is slowly varying and thereforeNow, sincewe get that for the condition (A3) to be fulfilled, it is sufficient that the right-hand side tends to zero as , i.e.,or, equivalently,

- Let the norming constants and be chosen in the form (12). Then is the cdf of the Gumbel law ifAs previously, we would like to replace (A5) with another condition without . Once more, we would like to recall that by slow variation ofFrom this we conclude thatand the fact that the right-hand side tends to zero as will imply (A5). In other words, we obtain the Gumbel limit ifor, equivalently, if

- (a)

- Let us first consider the case as . Then one can take and find as the solution to the equationThe limit for the second component in (A1) coincides with the corresponding one in item 2(i) (and leads to the cdf of the Fréchet law), while for the first component we getThe value of the latter limit is zero for all fixed since as , and therefore the limit distribution is Fréchet.

- (b)

- Now, let be such that as . Then the same choice of norming constants as when as leads to the same limits as before. However, the value of (A7) now depends on x, namely,Thus, in this case the limit distribution is equal toAn interesting point is that we get the limit distribution that is not from the extreme value family, having an atom at .

- (c)

- Finally, let be such that as . Then the normalising sequence can be chosen as in item 1, and for the first component we getwhile for the second oneTherefore, in this case the limit distribution is again Gumbel.

Appendix C. Limit Law for the Truncated RV Distribution

Lemma A1.

Let be the upper-truncated regularly varying distribution defined as (15). Then is in the maximum domain of attraction of the max-Weibull law having the distribution function

with .

Proof.

As it is known, for some if and only if and , see, e.g., [15]. Thus, for some if and only if

for some slowly varying function , or, equivalently, iff

Therefore, to prove this statement of this lemma, we need to show that for any , that is,

First,

Then, assuming that is continuous and differentiable,

Therefore,

Clearly, the latter limit is equal to one if , meaning that . □

Appendix D. Proof of Theorem 2

Step 1. Several simple cases. As in the proof of Theorem 1, we use the notation . We have

where we use that . Since , and as by slow variation of , we get

- (i)

- Let as . By slow variation of , as , therefore, the whole second component disappears. We deal with maxima of a Weibull random variable and obtain the Gumbel limit under the normalisation with in the form (A3).

- (ii)

- Let . By a similar argument as in the previous item,Under the same choice of normalising sequences, we getfor all fixed as . Therefore, the limit distribution is again Gumbel.

- (iii)

- Let as . The further analysis depends on the asymptotic properties of If (17) holds, the proof is based on the observation thatand therefore,From (17) it follow that for any the right-hand side tends to zero as , and therefore as . The rest of the proof in this situation follows the same lines as the proof of Theorem 1. Other cases are more complicated, and we divide the further proof into several steps.

Step 2. Case (18). Recalling again that , we get that

Therefore, for any as . Now, assume that is such that for all and n large enough. Then

and therefore the limit distribution does not exist. We conclude that there is a non-degenerate limit distribution only if for all and n large enough. In this case,

The condition leads to the inequality

for n sufficiently large. Finally, as takes only non-negative values, and the sequences tend to infinity as we conclude that the necessary condition for the existence of non-degenerate limit distribution is

- Now assume that (9) holds. In this case, (A10) can be violated. In fact,with some . From (18), it follows that the right-hand side is infinite if , and has an unknown asymptotic behaviour otherwise. The lower bound is given bywhere for , the right-hand side tends to zero as , while otherwise the asymptotic behaviour is again unknown. In this case, we conclude that if is such that (A10) holds, the non-degenerate limit distribution exists and is in fact the Gumbel distribution.

- Finally, in the case (10),because . Since by (A10) there exists such that the right-hand side tends to zero as , we get under proper normalisation the Gumbel limit distribution.

Step 3. Case (19).

- If (9) holds, then the result turns out to depend on the asymptotic behaviour of . Let us recall that is asymptotically equal to a constant.

- (a)

- If as , we have that as . Thus, as was argued above, the non-degerated limit exists if and only if (A10) holds for all x and n large enough. However, for any ,and therefore the assumption (A10) is violated due to (9). Thus, in this case there exists no non-degenerate limit distribution.

- (b)

- Now consider the case for some as . Let us fix in the form (13). The inequality is equivalent to Under this normalisation, we haveand therefore

- (c)

- If as , one can take the norming constants as in the previous item and obtain the Fréchet limit distribution since and as . The last thing which is crucial here is to check that for all . This inequality follows from

- Finally, let us consider the case (10). As in the previous situations, the limit distribution depends on the asymptotic behaviour of .

- (a)

- Let as . Since then as , we conclude that the non-degenerate limit exists only if (A9) holds. In the considered case, (A9) is equivalent toThe normalising sequence (12) again leads to the Gumbel limit distribution.

- (b)

- If for some as , we have that .

- If , a linear normalising sequence as in (12) leads to the Gumbel limit, since for all and n large enough; see the previous item.

- Therefore, we getAs we see, the limit distribution does not belong to the extreme value family, and has an atom at .

- If , the choice (13) leads to the discrete limit distribution having a unique atom at with probability mass

- (c)

- Lastly, let be such that as . Then the Gumbel limit can be obtained under the normalisation (12) since as , see item (i,c) in Theorem 1. This observation completes the proof.

References

- van den Berg, J.; Nolin, P. Near-critical percolation with heavy-tailed impurities, forest fires and frozen percolation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.08181. [Google Scholar]

- Grabchak, M.; Molchanov, S. Limit theorems and phase transitions for two models of summation of independent identically distributed random variables with a parameter. Theory Prob. Appl. 2015, 59, 222–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, V. Sums of Independent Random Variables; Springer Science & Business Media: Norwell, MA, USA, 2012; Volume 82. [Google Scholar]

- Meerschaert, M.; Scheffler, H.-P. Limit Distributions for Sums of Independent Random Vectors: Heavy Tails in Theory and Practice; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2001; Volume 321. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, A.; Hüsler, J. Condition for the convergence of maxima of random triangular arrays. Extremes 2003, 6, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.; Coles, S.; Hüsler, J. Maxima of Poisson-like variables and related triangular arrays. Ann. Appl. Probab. 1997, 7, 953–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dkengne, P.S.; Eckert, N.; Naveau, P. A limiting distribution for maxima of discrete stationary triangular arrays with an application to risk due to avalanches. Extremes 2016, 19, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirlant, J.; Fraga, A.I.; Gomes, I. Tail fitting for truncated and non-truncated Pareto-type distributions. Extremes 2016, 19, 429–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chakrabarty, A.; Samorodnitsky, G. Understanding heavy tails in a bounded world or, is a truncated heavy tail heavy or not? Stoch. Model. 2012, 28, 109–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laherrere, J.; Sornette, D. Stretched exponential distributions in nature and economy: “Fat tails” with characteristic scales. Eur. Phys. J. -Condens. Matter Complex Syst. 1998, 2, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malevergne, Y.; Pisarenko, V.; Sornette, D. Empirical distributions of stock returns: Between the stretched exponential and the power law? Quant. Financ. 2005, 5, 379–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, N.H.; Goldie, C.M.; Teugels, J.L. Regular Variation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick, S. Extreme Values, Regular Variation and Point Processes; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mikosch, T. Regular Variation, Subexponentiality and Their Applications in Probability Theory; Report Eurandom; Eurandom: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 99013. [Google Scholar]

- Embrechts, P.; Klüppelberg, C.; Mikosch, T. Modelling Extremal Events for Insurance and Finance; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Panov, V. Limit theorems for sums of random variables with mixture distribution. Stat. Probab. Lett. 2017, 129, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paulauskas, V. A note on linear processes with tapered innovations. Lith. Math. J. 2020, 60, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mandelbrot, B. The variation of certain speculative prices. J. Bus. 1963, 1, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cont, R. Empirical properties of asset returns: Stylized facts and statistical issues. Quant. Financ. 2001, 1, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aban, I.B.; Meerschaert, M.M.; Panorska, A.K. Parameter estimation for the truncated Pareto distribution. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2006, 101, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhov, Y.; Kelbert, M. Probability and Statistics by Example: Volume I. Basic Probability and Statistics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).