Abstract

Mutations on Brauer configurations are introduced and associated with some suitable automata to solve generalizations of the Chicken McNugget problem. Additionally, based on marked order polytopes, the new Diophantine equations called Gelfand–Tsetlin equations are also solved. The approach allows algebraic descriptions of some properties of the AES key schedule via some Brauer configuration algebras and suitable non-deterministic finite automata (NFA).

1. Introduction

Chicken McNuggets are one of the most sold products of the international fast-food restaurant chain McDonald’s. Shortly after their introduction in 1979, they began to be sold in packs of 6, 9, and 20 pieces. Nowadays, several choices of this product can be ordered, which naturally generates different types of Diophantine equations. For instance, the first three types of packs give rise to the following problem [1]:

Problem 1.

What numbers of chicken McNuggets can be ordered using only packs with 6, 9, or 20 pieces?

Problem 1 is currently called the chicken McNugget problem (CMP), which defines the following Diophantine equation:

where n is the number of ordered pieces.

CMP is a version of the postage stamp problem or Frobenius coin problem or knapsack problem, which can be defined as follows:

Problem 2.

Given a set of k objects with predetermined values , what possible values of n can be had from combinations of these objects?

Positive integers satisfying the CMP are known as McNugget numbers. Sequence A065003 in the OEIS is the list of not McNugget numbers. Actually, regarding these numbers, the following proposition holds:

Proposition 1

([1], Proposition 1.1). Any positive integer is a McNugget number.

CMP deals with a more wide kind of problems based on the number of lattice points in a convex polytope P, i.e., to determine , where is a integral matrix and is an integral m-vector. For instance, if then , , [2]. Actually,

The number of solutions of equations with the form was studied by Sylvester [3] who called denumerant the function , which counts the number of non-negative representations of b by . Notice that, is actually the number of partitions of b whose summands or parts are taken (repetitions allowed) from the sequence . Recall that a partition of a positive integer n is a finite non-increasing sequence of positive integers , such that .

Sylvester proved that the generating function of is given by the identity [3,4]

As Ramírez-Alfonsín pointed out in [4] finding formulas for denumerants is very difficult since even the problem of determining if is an -complete problem.

It is worth noting that Euler [4,5,6] pointed out that the generating function of the number of non-negative solutions of a system of linear equations with the form is equal to the coefficient of in the expansion of

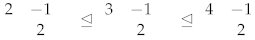

Gelfand–Tsetlin polytopes (or GT-polytopes) are another kind of polytopes whose enumeration gives rise to interesting problems in combinatorics, Diophantine analysis, and many other fields. We recall that a triangular integer array with the shape:

Given , the Gelfand–Tsetlin polytope is the convex polytope of patterns satisfying in addition that

It is worth noting that much of the theory of representation of the general linear Lie algebra (which consists of complex matrices with the usual matrix commutator) is based on a result of Gelfand and Tsetlin related with the enumeration of lattice points in GT-polytopes [7,8]. Actually, it is known that if U is the subspace of an irreducible representation V of with highest weight and then d is given by the number of integral points in .

Contributions

The main contribution of this paper is the introduction of the novel notion of the mutation of a Brauer configuration and its properties. Such mutations and their specializations allow solving different types of Diophantine problems. For instance, specializations of some mutations can be used to find out the Frobenius number of variations of some Diophantine equations called Gelfand–Tsetlin equations of the form , with suitable positive integers , for each . For these particular equations, we prove that there exists a solution if the constant term d is the number of Gelfand–Tsetlin patterns of a given type. To achieve that, we define some marked posets whose points are in bijective correspondence with some classes of Gelfand–Tsetlin patterns.

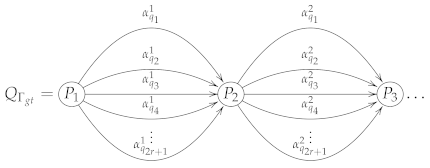

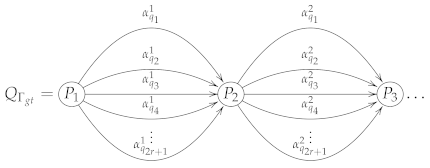

Specializations of mutations and suitable automata are also used to solve Diophantine problems of type , which arise from the research of generalizations of denumerants. Such a problem is defined as follows:

Find out positive integers such that for positive integers and , it holds that

where is a fixed set of positive integers.

As an application, we note that the AES key schedule is nothing but the specialization of a mutation. Thus, the algebraic properties of the corresponding Brauer configuration algebra allow the description of some characteristics of an AES key. It is worth noting that the use of Brauer configuration algebras to analyze the structure of an AES key does not appear in the literature, neither focused on the theory of representation of algebras nor focused on cryptography.

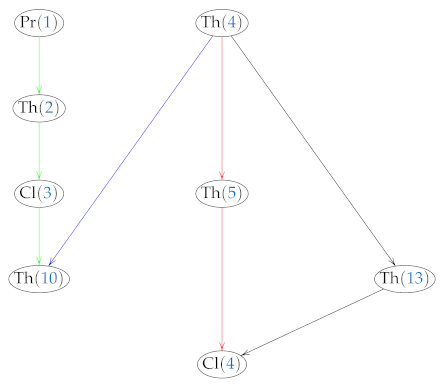

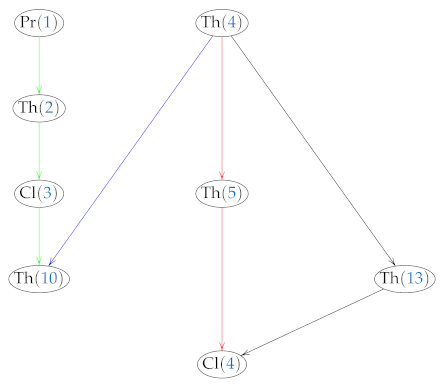

The following diagram (7) shows a way that some of the main results presented in this paper are related. In this case, Th(i), Cl(i) and Pr(i) denote Theorem i, Corollary i, and Proposition i, respectively.

This paper is organized as follows; basic notation and definitions to be used throughout the paper are given in Section 2. In particular, we introduce an algorithm to build Brauer configuration algebras. The notion of mutation associated with Brauer configurations is also introduced in Section 2.3.2. In Section 3, we prove results regarding Gelfand–Tsetlin patterns. Gelfand–Tsetlin equations, and Gelfand–Tsetlin numbers are introduced in this section as well. In Section 4, we give properties of some Diophantine equations whose solutions are given by mutations of some Brauer configurations. In this section properties of the AES key schedule are described in terms of specializations of mutations of suitable Brauer configurations. Conclusions are given in Section 5.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we introduce basic definitions and notation to be used throughout the paper. Henceforth, we will use the customary symbols , , and to denote the set of natural numbers, integers, and real numbers, respectively.

2.1. On the Frobenius Number

If are positive integers then the set S of all integers which can be presented in the form [1]:

is a submonoid of . We let denote the set , numbers are said to be generators of S, which is called a numerical monoid, e.g., is the chicken McNugget monoid generated by 6, 9, and 20. S is said to be a numerical semigroup if .

The following result regards numerical semi-groups.

Theorem 1

([9], p. 7). If are positive integers, then they generate a numerical semigroup if, and only if, .

If are positive integers, then the Frobenius number of denoted is the largest positive integer n, such that . For instance, , (see Proposition 1).

The following result is a version of Ramírez-Alfonsín [4] of a theorem given by Roberts [10] regarding Frobenius numbers.

Theorem 2

([4], Theorem 3.3.2). Let and s be positive integers with . Then

where is the largest integer less than or equal to x.

In the general case, there is no known formula for the Frobenius number of the k-generated numerical semigroup S, but for k fixed, there is an algorithm that computes the Frobenius number in polynomial time. Actually, Ramírez-Alfonsín proved that the knapsack problem can be reduced to the Frobenius problem in polynomial time [11].

Let , we say that x divides y in if there exists , such that .

We call a non-zero element irreducible if whenever , either or (hence, x is irreducible if its only proper divisors are only 0 or itself).

The following result determines which elements are irreducible in a numerical monoid.

Proposition 2

([1], Proposition 3.1). If is a numerical monoid, then its irreducible elements are precisely .

Corollary 1

([1], Corollary 3.2). The irreducible elements of the McNugget monoid are 6, 9, and 20.

2.2. Path Algebras

In this section, we give a brief discussion on quivers, path algebras, and their ideals based on the work of Assem et al. [12].

A quiver is a quadruple consisting of two sets: (whose elements are called points or vertices) and (whose elements are called arrows), and two maps which associate to each arrow its source and its target , respectively. Note that, under these circumstances, a quiver is nothing but an oriented graph without any restrictions as to the number of arrows between two points, to the existence of oriented cycles or loops.

An arrow of source and target is usually denoted by . A quiver is usually denoted by or even simply by Q.

A path of length with source a and target b (or more briefly, from a to b) is a sequence where for all , and . Such a path is denoted by .

We let () denote the length of a path P (the set of all paths P for which ). We also agree to associate to each point a path of length 0, called the trivial or stationary path at a, and denoted by . If X is a set of paths in a quiver Q then .

Example 1.

The following is an example of a quiver Q with three vertices , and and two arrows and . Note that, , and . Thus, .

If is an algebraically closed field then the path algebra of Q is the -algebra whose underlying -vector space has, as its basis, the set of all paths of length in Q and such that the product of two basis vectors is given by the usual concatenation of paths. For instance, is a basis of the algebra , where Q is the quiver given in (10).

Let Q be a finite and connected quiver. The two-sided ideal of the path algebra generated (as an ideal) by the arrows of Q is called the arrow ideal of . A two-sided ideal I of is said to be admissible if there exists , such that .

If I is an admissible ideal of , the pair is said to be a bound quiver. The quotient algebra is said to be the algebra of the bound quiver or, simply, a bound quiver algebra.

Let Q be a quiver. A relation in Q with coefficients in is a -linear combination of paths of length at least two having the same source and target. Thus, a relation is an element of , such that

where the are scalars (not all zero) and the are paths in Q of length at least 2 such that, if , then the source (or the target, respectively) of coincides with that of .

If , the preceding relation is called a zero relation or a monomial relation. If it is of the form (where and are two paths), it is called a commutativity relation.

If is a set of relations for a quiver Q such that the ideal they generate is admissible, we say that the quiver Q is bound by the relation or by the relations [12].

Henceforth, we let denote the radical of a path algebra , which is the intersection of all maximal ideals. Actually, if I is an admissible ideal of , it holds that .

If ≺ is an admissible well-ordering on the set of paths, i.e., ≺ is a well-ordering such that

- If where and are both not-zero or ;

- if then .

Then the tip of an element is the maximal path w with respect to ≺, such that w has a non-zero coefficient in x when it is writing as a linear combination of the elements of a fixed basis of . is the set of tips of elements of elements in X [13].

Let I be an ideal in a path algebra and let . If then is a Gröbner basis for I with respect to ≺.

2.3. Brauer Configuration Algebras

Brauer configuration algebras are multi-serial path algebras introduced recently by Green and Schroll in [14]. These algebras constitute a generalization of Brauer graph algebras, which have as one of their properties that its representation theory is encoded by some combinatorial data based on graphs.

The following is a description of the structure of Brauer configuration algebras as the first author and Espinosa and Green and Schroll present in [14,15], respectively.

A Brauer configuration is a quadruple of the form , where

- is a set whose elements are called vertices, ;

- is a finite collection of multisets called polygons, such that if then ;

- is an integer valued map, (i.e., for each vertex , it holds that ) called the multiplicity function;

- is a well-ordering < defined on . Such that for each vertex , the collection consisting of all polygons of where occurs (counting repetitions) is ordered in the form (, for ). Where, is a sequence of the form . If it is assumed that and then a new circular relation is added. is called the successor sequence at the vertex and ;

- denotes the number of times that a vertex occurs in a polygon V and the sum is said to be the valency of , denoted .;

- A vertex is truncated if , it is non-truncated if . Vertices are either truncated or non-truncated (i.e., , where () is the set of truncated (non-truncated) vertices), if then . A Brauer configuration without truncated vertices is reduced, these types of configurations are used to construct suitable quivers called Brauer quivers [14].

Following the Green and Schroll ideas [14], Algorithm 1 builds the Brauer quiver and the Brauer configuration algebra induced by the Brauer configuration , where is an admissible ideal (see Remark 2).

| Algorithm 1: Construction of a Brauer configuration algebra |

|

Remark 1.

In the last few years, the computational aspects of the theory of representation of quivers have been extensively studied. For instance, Struble [13] gave results regarding the complexity of algorithms based on Gröbner bases used to construct path algebras and their dimensions.

Struble proved that if I is an ideal of a path algebra and is a Gröbner basis for I under some admissible ordering ≺. Then there exist algorithms to determine whether is finite-dimensional in time, to compute in time. Additionally, Haugland [16] proved that if X is the matrix, which simultaneously encodes all the constraints imposed on any homomorphism between two representations and of a quiver Q, then there is an algorithm, which computes a basis of in , where r (c) is the number of rows (columns) of the matrix X.

The complexity of algorithms used to compute the center of an associative algebra has been also studied by Strubel who described an algorithm, which finds the center of a path algebra with dimension d and h generators in . Where, means that up to elements in Q have non-zero coefficients, the algorithm develops multiplications in Q, and denote the time that the algorithm takes making scalar multiplications and comparisons to determine if a given element is in the field , is the running time that a specialized algorithm reduces an element of the basis of to a normal form.

Several up-to-date software packages have been designed to develop basic operations and testing conjectures on path algebras and representation of quivers. For instance, the GAP package QPA [17] extends the GAP functionality for computations with finite-dimensional quotient path algebras, whereas King et al. have been working on the implementation of Sage packages [18] with the same purposes as QPA.

Remark 2.

Let be the Brauer configuration algebra associated with a reduced Brauer configuration Γ (i.e., truncated vertices occur only in polygons with two vertices). Denote by the canonical surjection then is denoted by , for

Henceforth, if no confusion arises, we will assume notations Q, I, and instead of , and , for a quiver, an admissible ideal, and the Brauer configuration algebra induced by a fixed Brauer configuration .

Example 2.

As an example of the application of Algorithm 1, consider the following reduced Brauer configuration:

The following is a list of special cycles:

The admissible ideal is generated by the following relations:

The next result regards the dimension of a Brauer configuration algebra.

Proposition 3

where denotes the number of vertices of Q, denotes the number of arrows in the -cycle and .

([14], Proposition 3.13). Let Λ be a Brauer configuration algebra associated with the Brauer configuration Γ and let be a full set of equivalence class representatives of special cycles. Assume that for , is a special -cycle where is a non-truncated vertex in Γ. Then

Proposition 4

([14], Proposition 3.6). Let Λ be the Brauer configuration algebra associated with a connected Brauer configuration Γ. The algebra Λ has a length grading induced from the path algebra if, and only if, there is an such that for each non-truncated vertex .

The following result regards the center of a Brauer configuration algebra.

Theorem 3

([19], Theorem 4.9). Let Γ be a reduced and connected Brauer configuration and let Q be its induced quiver and let Λ be the induced Brauer configuration algebra such that then the dimension of the center of Λ denoted is given by the formula:

where .

Example 3.

The dimension of the algebra defined by (12) and (13) is given by the following identity:

Note that,

2.3.1. The Message of a Brauer Configuration

The notion of labeled Brauer configurations and the message of a Brauer configuration were introduced by Fernández et al. to define suitable specializations of some Brauer configuration algebras [15,20]. According to them, since polygons in a Brauer configuration are multisets, it is possible to assume that any polygon is given by a word of the form

where for each i, , .

The message is, in fact, an element of an algebra of words associated with a fixed Brauer configuration such that for a given field the word algebra consists of formal sums of words with the form , is the empty word, and for any . The usual word concatenation gives the product in this case. The formal product (or word product)

is said to be the message of the Brauer configuration Γ.

2.3.2. Mutations

Define a seed , where with , , , and a field for a suitable irreducible polynomial of degree 1.

is a Brauer configuration for which;

For the orientation in successor sequences, it is considered the order .

A mutation is given by a Brauer configuration and a vector with , , such that:

Note that, if the indices of the original seed are considered then polygons in can be written as follows:

with , for some suitable, , and . We let denote the shift vector such that .

For successor sequences, the orientation is defined in such a way that,

It turns out that according to the indices assumed for the original seed, the ith mutation has the form:

Brauer configurations obtained from mutations are said to be Brauer clusters. Polygons are called cluster polygons.

For a fixed positive integer , the -Brauer cluster, is a Brauer configuration,

such that:

- ;

- consists of messages of the Brauer clusters , ;

- ;

- If denotes the message associated with the ith Brauer cluster then for successor sequences, it is assumed the order .

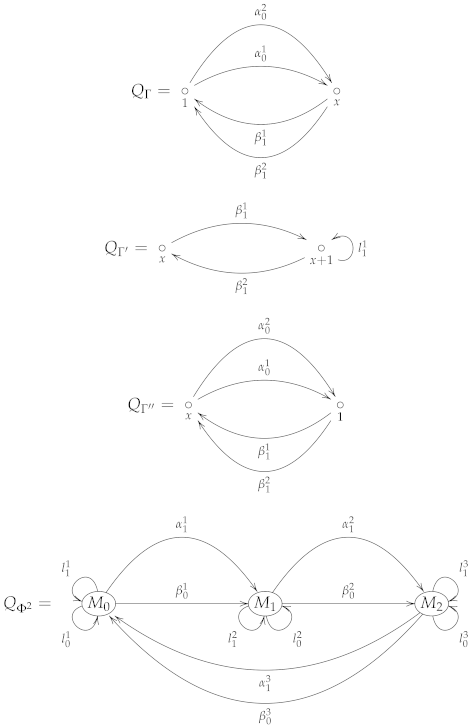

Example 4.

As an example, in the sequel we describe mutations of the following seed , where .

Successor sequences at 0 and 1 are defined as follows:

The first mutation is defined as follows:

In this case 1 is the only non-truncated vertex with a successor sequence of the form:

The second mutation is described as follows:

In this case, the successor sequences at 0 and 1 are

The 2-Brauer cluster has the following form:

For successor sequences, it holds that:

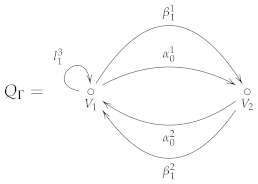

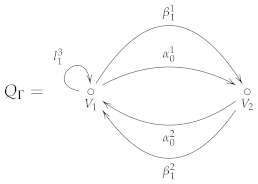

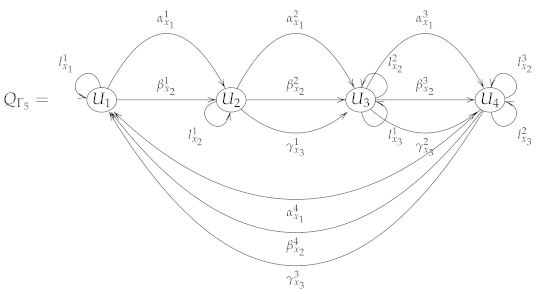

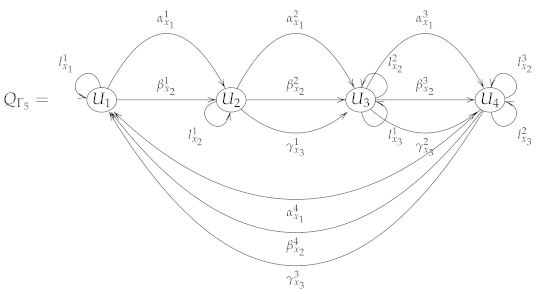

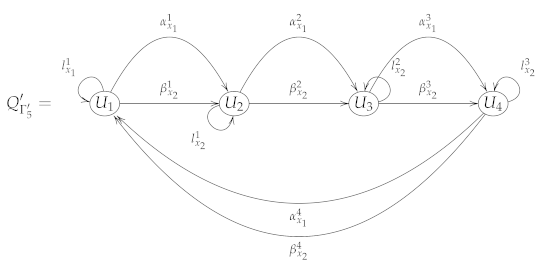

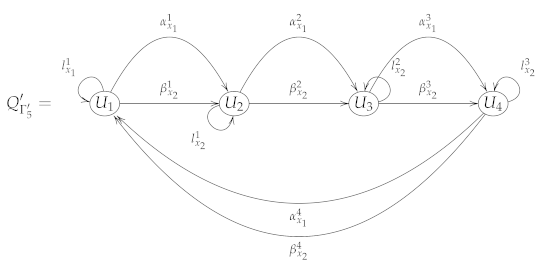

The following , and are the Brauer quivers of all these mutations and of the 2-Brauer cluster .

The admissible ideal I in the Brauer configuration algebra is generated by the following relations:

- , , for all possible values of i and j;

- , , , for all possible values of i and r;

- , , , for all possible values of , and s.

Theorem 4.

For the Brauer configuration algebra induced by the Brauer configuration (see (20)) is connected and reduced.

Proof.

Since each polygon contains at least one 0 and at least one 1, we conclude that does not contain truncated vertices. The result follows provided that . □

Theorem 5.

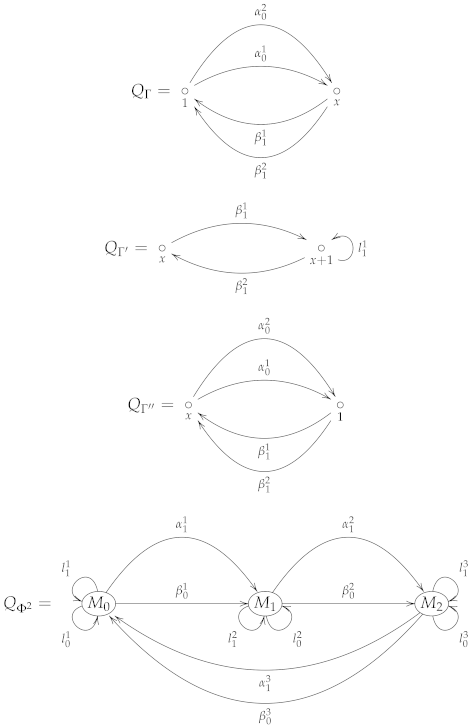

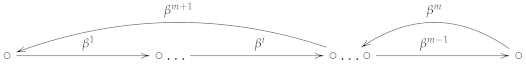

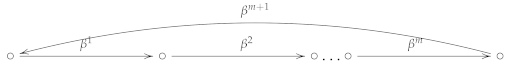

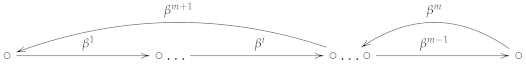

If is a finite field then the set of -Brauer clusters obtained by mutation is finite, and the special cycle of maximal length has one of the two shapes (26) or (27). Moreover, there exists , such that for a given initial seed .

where .

where .

Proof.

Every mutation is uniquely determined by . Since, for any then . Note that, since the set of mutations is finite, there exist integers m and n, such that . If and then the maximal special cycle of the quiver obtained after n mutations has the form (26), otherwise the special cycle of the quiver after mutations has the form (27). We are done. □

Remark 3.

For and a fixed seed, the dimension of an algebra and its center can be estimated by using some statistical methods. For instance, we use a sample of random seeds to obtain confidence intervals for these values. Such samples allow us to infer that if , then

where denotes the probability of an event X.

Remark 4.

For the sake of applicability, the definition of mutation of a Brauer configuration has been given by taking into account that elements constituting a seed are elements of finite products of finite fields. However, it can be extended to arbitrary rings, in such a case, if and are rings then any map , can be used to transform a given seed into a Brauer cluster of the form .

2.4. Deterministic and Non-Deterministic Automata

In this section, we recall definitions of deterministic and non-deterministic automata as Rutten et al. present in [21]. We use these definitions to interpret Brauer configuration algebras as automata with acceptance language given by relations generating suitable admissible ideals.

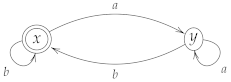

Given an alphabet A, a deterministic automaton is a pair consisting of a (possibly infinite) set X of states and a transition function . The following is an illustration of this kind of transitions, where [21].

If denotes the empty word then , for any and with .

A deterministic automaton can be decorated by means of a coloring function , such that if x is an accepting (or final) state, , if x is a non-accepting state. A triple is said to be a deterministic colored automaton. In the following diagram, an accepting state is denoted with a double circle, x is an accepting state, whereas y is a non-accepting state.

Given a deterministic colored automaton and a state , the set

is called the language accepted or recognized by the automaton starting from the state x. A deterministic automaton can also has an initial state represented by a function . The triple is said to be a deterministic pointed automaton.

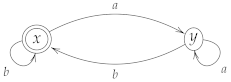

A non-deterministic automaton is a pair consisting of a set X (possibly infinite) of states and a transition function , that assigns to each letter and to each state a finite set of states [21]. If to each state it is assigned a single new state, the definition of a deterministic automaton is recovered. As in the deterministic case, a state x in a non-deterministic automaton can be either accepting () or non-accepting (); and , . A triple is called a colored non-deterministic automaton.

If the set of states X is finite then the automaton is said to be a deterministic (non-deterministic) finite automaton, denoted DFA (NFA), respectively.

A regular language associated with a Brauer configuration algebra

Automata associated with path algebras have been studied by Rees [22], who introduced some automata associated with some string algebras, such automata were used by her to describe indecomposable representations over these types of algebras, she points out that the set of strings defining representations of string algebras, and many other bounded path algebras, constitute a regular set. In this section, we follow Rees ideas to describe an automaton associated with a Brauer configuration algebra.

Values of the map can be obtained by endowing to the successor sequences a length-lexicographic order, in this case, both and are well-ordered sets with partial orders ≺ and <, respectively. In such a way that initial states in the corresponding automaton are given by minimal successor sequences (see Algorithm 1). Note that, if denotes a successor sequence starting in a polygon U with , and if , and , then and .

A Brauer configuration algebra induced by a Brauer configuration has associated a regular language , where the alphabet , each letter corresponds to a unique arrow in . Each path corresponds to a word .

Two words are equivalent (i.e., ) if their corresponding paths are equivalent as elements of the Brauer configuration algebra. In this case, if is a successor sequence associated with the vertex , then denotes the word associated with the corresponding special cycle up to equivalence. If then (final vertices of special cycles are final states up to equivalence).

In the associated automaton of a Brauer configuration algebra, polygons are states. Actually, all states we represent are accepted states. The transition between states is given by the order <, in other words, if is the letter associated with an arrow , that is, then is a transition from to . Note that, if belongs to the admissible ideal I, with then it is not accepted as a word in if .

Note that, according to the automaton associated with the Brauer configuration defined by (12) and (13), it holds that is the initial and final state and

2.5. Enumeration of Gelfand–Tsetlin Patterns

In this section, we recall some well-known results regarding the enumeration of GT patterns. Furthermore, we introduce the notion of the heart of a GT pattern which allows us to define posets and marked order polytopes associated with the number of some GT patterns [2,7,8,23,24].

If is an integer partition and is a finite-dimensional irreducible representation of with highest weight then a basis of is parametrized by GT patterns associated with . These are arrays of integer row vectors with the shape:

such that the upper row coincides with and the following conditions hold:

This setting together with terms of the form allow establishing the existence of a basis of parametrized by , such that the action of generators of are given by some Gelfand–Tsetlin formulas [7,8].

A GT pattern with first row of the form is called a monotone triangle of length n. It is also known that there is a bijection between GT patterns with first row and column-strict plane partitions of type ( parts in row i) and largest part [23,24].

The following theorem regarding monotone triangles was given by Zeilberger in 1996.

Theorem 6

([25], Main Theorem). The number of monotone triangles of length n with bottom entry is equal to

Note that, , where denotes the number of standard elements of such that , for . In particular, .

3. Gelfand–Tsetlin Equations and Diophantine Equations of Type

In this section, Gelfand–Tsetlin equations and Gelfand–Tsetlin numbers are introduced. Solutions of this kind of equations are proposed via some order marked polytopes. Whereas, solutions of Diophantine equations of type are obtained by using some suitable non-deterministic automata associated with mutations of Brauer configurations.

3.1. The Heart of a GT Pattern

For , a subarray of is said to be the heart or GT-heart of denoted .

For fixed, it is possible to define an order ⊴ on the set of GT-hearts over (associated with GT patterns with fixed first row) whose covers are defined as follows:

if and , with , for some .

If denotes the set of Gelfand–Tsetlin arrays with as heart, then two hearts and are said to be equivalent denoted , provided that . Thus, is a poset endowed with an equivalence relation.

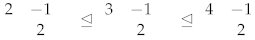

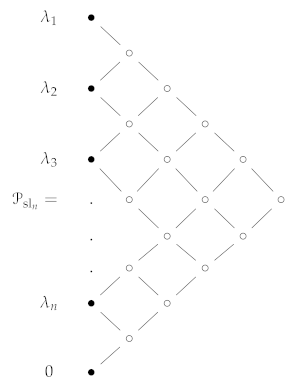

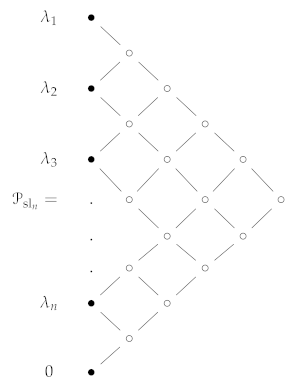

We let or simply denote the poset of hearts associated with a given Gelfand–Tsetlin pattern with a weight of length n, such that .

Example 5.

If is a suitable weight for , then the following is a three-point chain of :

We have the following result for GT patterns with first row of the form:

Theorem 7.

The number of GT patterns over defined by a weight vector of the form is given by the formula .

Proof.

It suffices to observe that for , it holds that . □

If denotes the number of Gelfand–Tsetlin patterns with the same heart then the following result holds.

Proposition 5.

If , , and are such that and then .

Proof.

If the different Gelfand–Tsetlin patterns are obtained by keeping the heart without changes and reducing one entry in one unit only then the number of such Gelfand–Tsetlin arrays are given by adding some suitable integers in the form:

in particular, and . In the case, , , and

For arrays with then , , and the construction of the remain ’s goes on until reaching all arrays for . If then we have sums of the form , , if in the heart , , if in the heart , and so on until the case for which and . □

3.1.1. Marked Posets and Marked Polytopes

In this section, we describe a special class of marked posets and marked polytopes introduced by Fourier in [26]. We also prove that some posets of type are marked by the number of some suitable Gelfand–Tsetlin arrays.

Let be a finite poset and a subset A of containing at least all maximal and all minimal elements of , we set:

and call the triple a marked poset. Then the marked chain polytope associated with is defined:

while the marked order polytope is defined as

where , (the definition of marked order polytope is also valid if in is considered the usual order ≤ and the order ⪯ in is reversed).

The marked poset is regular if for all in A, , and there are no obviously redundant relations.

If , then a chain is said to be saturated, if for each i, , the relation is a cover (i.e., if there exists , such that , then either or ).

Let be a regular marked poset then the number of facets in the marked order polytope is equal to the number of cover relations in .

If denotes the number of saturated chains , , then the number of facets in the marked chain polytope is equal to +.

If is the Lie algebra of matrices with trace zero and the usual Lie bracket. Then, for each n and , let be the following marked poset with cover relations [26].

Let and let be marked with , then:

where is the corresponding Catalan number.

The associated marked order polytope is known as the Gelfand–Tsetlin polytope associated with the partition .

The following result regards posets of type .

Proposition 6.

For , and , If denote the set of numbers ’s given by identities (29) and (30). Then (see (31)).

Proof.

Consider the following relation defined by hearts associated with suitable Gelfand–Tsetlin arrays.

Then, if or and the number of Gelfand–Tsetlin arrays is given by a sequence with the form then covers , and the associated sum to has the form with . Note that, if and are incomparable then . □

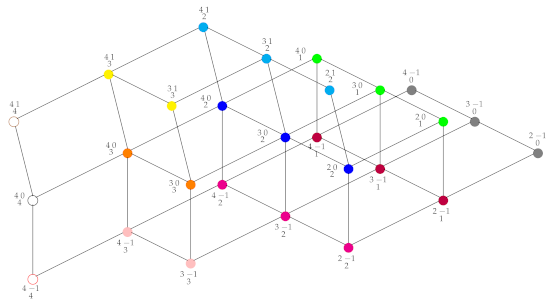

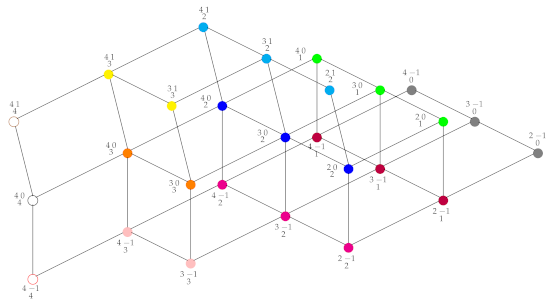

The next diagram illustrates poset where points with the same color are equivalent:

Corollary 2.

For and , the number of facets in the marked order polytope associated with is

Proof.

If is the largest integer associated with the hearts of then subposet , which contains all the hearts with this shape is equal to the poset . Thus, the number of facets in the corresponding order polytope equals . Note that, , , if , and . Therefore the number of covers of the form since then , where denotes the ith triangular number. Therefore, as desired. □

3.1.2. Gelfand–Tsetlin Equations

Gelfand–Tsetlin equations are Diophantine equations of the form:

where c and d are positive integers and () denotes the mth square (triangular) number. Note that, if then , , and are solutions of , such numbers give the number of some standard Gelfand–Tsetlin arrays, for which and (see Theorem 7). Numbers d, which correspond to solutions of a given equation are said to be Gelfand–Tsetlin numbers of type . Note that, there is not a Frobenius number associated with the equation .

Corollary 3.

For and sums (see identities (29) and (30)) associated with points are Gelfand–Tsetlin numbers of type .

Proof.

If then Propositions 7, 5, and 6 allow us to establish identities of type , for . Thus, (see Equation (35)). □

The following table shows Frobenius numbers associated with some Gelfand–Tsetlin equations:

| Gelfand–Tsetlin Equation | Frobenius Number |

| gt(4) | 33 |

| gt(5) | 56 |

| gt(6) | 133 |

| gt(7) | 179 |

| gt(8) | 181 |

| gt(9) | 299 |

| gt(10) | 394 |

| gt(11) | 535 |

| gt(12) | ∞ |

We let denote the subposet of consisting of hearts with a fixed entry , with the shape , the corresponding equivalence classes have associated a unique number of the form . If it is assumed that for any of these numbers, then the following result holds:

Theorem 8.

Numbers with associated with equivalence classes of points of the subposet define a Brauer configuration algebra with length grading induced from the path algebra .

Proof.

If for any number then such an assignation defines the Brauer configuration , such that:

where denotes the word associated with the polygon (see (15)). In this case the Brauer quiver has the form:

The admissible ideal is generated via equivalence of special cycles, products of the form with , , where is a special cycle and is an arrow connecting polygons and . Since , for any , the result follows as a consequence of Theorem 4. □

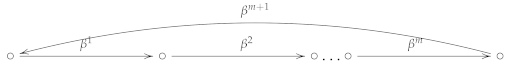

3.2. A Relationship between Brauer Configuration Algebras and Gelfand–Tsetlin Equations

For , let us consider a seed , such that where is the ring of polynomials over in variables , and .

is a Brauer configuration such that:

- ;

- ;

- For , the word associated with the polygon is defined as follows:

- The successor sequences at vertices , and have the following forms:where, denotes a sequence of the form and ;

- For any , it holds that, ;

The following is the Brauer quiver defined by the Brauer configuration .

For fixed, the ideal of the Brauer configuration algebra is generated by the following relations:

- Special cycles associated with vertices , are equivalent;

- If a is the first arrow of a special cycle then ;

- , if and ;

- , for all the possible products of , , and ;

- , for all the possible values of and s, denotes a suitable loop;

- .

For , the mutation of a seed is defined as follows:

- ;

- , ;

- The Brauer configuration is defined in such a way that:

- (a)

- ;

- (b)

- ;

- (c)

- For , the word associated with the polygon is given by the following identities:

- (d)

- , if ;

- (e)

- The successor sequences at and are defined by the following chains:

- (f)

- For any , it holds that, .

The following is the Brauer quiver defined by the Brauer configuration .

The Brauer configuration algebra is bounded by the ideal , whose relations are obtained by restricting to and the relations contained in I.

The following results regards algebras and their corresponding mutations for fixed.

Theorem 9.

For fixed, it holds that

where and .

Proof.

. Since , and , the first identity follows.

The second identity holds provided that in , , and .

The third identity is obtained by taking into account that the number of loops in .

Since . Thus, . We are done. □

If we specialize the message () of the Brauer configuration () by taking , , and then the corresponding specialized message () gives rise to a vector (), such that:

The following theorem establishes a relationship between Gelfand–Tsetlin equations, Frobenius numbers, and specialized messages of Brauer configurations and .

Theorem 10.

For , a -tuple is solution of the Gelfand–Tsetlin equation (35) if, and only if, λ is a solution of the equation

where . Moreover, the Frobenius number satisfies the following identity:

Proof.

The result follows provided that , if , and . Since then identity (46) is obtained from Theorem 2 by taking , , and . □

4. On Diophantine Equations of Type

In this section, we give criteria to solve equations of type , i.e., Diophantine equations of the form:

with fixed , , and .

Regarding equations of type (45), we have the following results:

Theorem 11.

If is solution of and , then is solution of the Diophantine equation .

Proof.

If is solution of then and . Thus,

Therefore, is solution of the desired equation.

Conversely, if is solution of then the result holds provided that , if . □

Theorem 12.

An equation of type with has at least one solution if, and only if, .

Proof.

If and for then for

it holds that , where () denotes the ith coordinate of the vector (), in general , if . Therefore, the minimum value of for which equation has a solution is attained at , whereas the maximum value of satisfying the condition is attained at . Thus equation has a solution if the following conditions for and hold:

Therefore,

Additionally,

Theorem 13.

For a fixed positive integer , , and a fixed seed (see (17) and (18)), the Brauer configuration algebra induced by the Brauer configuration

has associated a finite non-deterministic automaton whose states are given by solutions of a problem of type with , and

where is a suitable transformation between Brauer configurations.

Proof.

Since the length of the message then it consists of lists of four bits. We let denote this set of lists. Define a map , such that , where is a notation for the hexadecimal numbering system . In this case, if .

The map T defines a new Brauer configuration , which we assume reduced without loss of generality. Each polygon consists of elements of the form with . Actually, if is the message of then is the message of . Additionally, if in then in ; and for any . Thus, the message is a word whose letters can be grouped according to its valency. Thus, has the form:

where is a multiset with and . Note that consists of all letters , such that , i.e, the message associated with can be written as

Therefore,

Then terms give a solution of a Diophantine equation of type

Since any Brauer configuration algebra defines a regular language, whose associated automaton uses arrows of the Brauer quiver as transitions between states given by polygons, which, in this case, are obtained by mutation. Then the probability that a given message M or Diophantine equation occurs after applying a mutation to a fixed seed is such that (see Remark 3), we conclude that the associated automaton is non-deterministic. □

Example 6.

Suppose that a seed is defined by the polynomial , and that we use set to denote polynomials. Then can be denoted as follows:

Then

which builds a solution of the Diophantine equation with the form:

For a given a polynomial the map associated with a mutation of the seed is defined in such a way that

The following is the list of vectors , .

For and , an element of a mutation is obtained from a seed with

by applying the following identities taking into account that for any t, is a matrix:

For , any mutation of this seed gives rise to a solution of a Diophantine equation of type with being a set of the form:

A cryptographic application

In this section, we give some properties of the AES key schedule based on the fact that such schedule arises from Brauer configurations, as described in (51) and its mutations are given by identities (52)–(54).

AES is a symmetric block cypher also considered as a substitution-permutation network, which was adopted in 2001 by the US government as the current standard cryptographic [27]. It is considered secure against different types of attacks. It requires keys of 128 bits (for 10 rounds), 192 bits (for 12 rounds), and 256 bits (for 14 rounds). Encryption and decryption algorithms are carried out via polynomials defined over suitable Galois fields. Many routers provide protocols WPA2-PSK (TKIP), WPA2-PSK (AES), and WPA2-PSK (TKIP/AES) as options to ensure Wi-Fi security. The new protocol WPA3 uses keys of 128 bits (CCMP-128), 192 bits (WPA3-Enterprise mode) to secure wireless computer networks.

In the cryptosystem AES, a plaintext, also called a state, is a sequence of 16 bytes, the encryption process also generates a 16-bytes sequence by using keys of 128, 192, or 256 bits. Such length depends on the number of rounds developed in the encryption process, 10, 12, or 14, respectively.

Each round in an encryption process requires 4 different transformations:

- SubBytes;

- ShiftRows;

- MixColumns;

- AddRoundKey.

For the last round the function MixColumns is not executed.

The next table gives all the possible outputs of the transformation SubBytes, whose operations are made modulo the polynomial as described in identities (52) and (53) [27]:

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| 0 | 63 | 7C | 77 | 7B | F2 | 6B | 6F | C5 | 30 | 01 | 67 | 2B | FE | D7 | AB | 76 |

| 1 | CA | 82 | C9 | 7D | FA | 59 | 47 | F0 | AD | D4 | A2 | AF | 9C | A4 | 72 | C0 |

| 2 | B7 | FD | 93 | 26 | 36 | 3F | F7 | CC | 34 | A5 | E5 | F1 | 71 | D8 | 31 | 15 |

| 3 | 04 | C7 | 23 | C3 | 18 | 96 | 05 | 9A | 07 | 12 | 80 | E2 | EB | 27 | B2 | 75 |

| 4 | 09 | 83 | 2C | 1A | 1B | 6E | 5A | A0 | 52 | 3B | D6 | B3 | 29 | E3 | 2F | 84 |

| 5 | 53 | D1 | 00 | ED | 20 | FC | B1 | 5B | 6A | CB | BE | 39 | 4A | 4C | 58 | CF |

| 6 | D0 | EF | AA | FB | 43 | 4D | 33 | 85 | 45 | F9 | 02 | 7F | 50 | 3C | 9F | A8 |

| 7 | 51 | A3 | 40 | 8F | 92 | 9D | 38 | F5 | BC | B6 | DA | 21 | 10 | FF | F3 | D2 |

| 8 | CD | 0C | 13 | EC | 5F | 97 | 44 | 17 | C4 | A7 | 7E | 3D | 64 | 5D | 19 | 73 |

| 9 | 60 | 81 | 4F | DC | 22 | 2A | 90 | 88 | 46 | EE | B8 | 14 | DE | 5E | 0B | DB |

| A | E0 | 32 | 3A | 0A | 49 | 06 | 24 | 5C | C2 | D3 | AC | 62 | 91 | 95 | E4 | 79 |

| B | E7 | C8 | 37 | 6D | 8D | D5 | 4E | A9 | 6C | 56 | F4 | EA | 65 | 7A | AE | 08 |

| C | BA | 78 | 25 | 2E | 1C | A6 | B4 | C6 | E8 | DD | 74 | 1F | 4B | BD | 8B | 8A |

| D | 70 | 3E | B5 | 66 | 48 | 03 | F6 | 0E | 61 | 35 | 57 | B9 | 86 | C1 | 1D | 9E |

| E | E1 | F8 | 98 | 11 | 69 | D9 | 8E | 94 | 9B | 1E | 87 | E9 | CE | 55 | 28 | DF |

| F | 8C | A1 | 89 | 0D | BF | E6 | 42 | 68 | 41 | 99 | 2D | 0F | B0 | 54 | BB | 16 |

The key schedule is the process for which all the keys to be used in the encryption process are generated. Such keys are called subkeys. For keys of 128 bits (or 16 bytes) of length, the process generates 11 subkeys, the initial key, the nine main rounds and the final round.

The expanded key can be seen as an array of 32-bit words numbered from 0 to 43 (0 for the initial key, which is the message of a Brauer configuration associated with an initial seed . and are described as in Example 6. Identities (51)–(54) are used to generate the schedule of the initial seed-key in terms of mutations of Brauer configurations), words that are a multiple 4 are calculated as follows:

- Applying the RotWord and SuBytes transformation to the previous word , (SubBytes (RotWord. In this case, the transformation RotWord is defined in such a way that RotWord. Note that, is given by the transformation defined by the identities (52);

- Adding (XOR) this result to the word 4 positions earlier plus a round constant called RCON. Such constants are given by identities (53);

- The remaining 32-bit words (i.e., those for which the index i is not a multiple of 4) are calculated by adding (XOR) the previous word , with the word four positions earlier. These operations correspond to the mutations of the Brauer configuration defined by formulas (52)–(54).

We let denote the nth subkey of an AES schedule, where the original key has 128 bits. Additionally, is the result of the AES schedule after the nth round.

Corollary 4.

There exists an integer N for which , for some .

Proof.

For , and vectors given in (53), it holds that the set of polygons (see (20)) of is obtained by applying the mutation rules (54) to the seed defined by , which is the message described as in identities (51). Thus, the message is the expanded key with subkeys given by messages of Brauer clusters obtained by mutation. That is, for a fixed j, it holds that . Since is finite the result holds as a direct consequence of Theorem 5. □

5. Conclusions

Mutations of Brauer configurations are a useful tool for solving Diophantine problems. They allow solving variations of Gelfand–Tsetlin equations and problems of type via suitable specializations. The AES key schedule is also a specialization of mutations of some Brauer configurations. Therefore, some properties of these types of procedures can be described in terms of the structure of the associated Brauer configuration algebra.

In what follows, we give a brief description of some of the main results of this paper.

- Theorem 4 establishes that the Brauer configuration algebra associated with a mutation process is connected and reduced;

- Theorem 5 gives properties of the cycles of a maximal length of Brauer quivers obtained by mutation;

- Theorem 7 gives a formula for the number of Gelfand–Tsetlin arrays with a weight vector of the form ;

- Proposition 5 establishes that equivalent triangular arrays of numbers called hearts have associated the same number of suitable Gelfand–Tsetlin arrays;

- Proposition 6 establishes that numbers given by identities (29) and (30) (which are parts of partitions of numbers ) constitute a marked poset. Corollary 2 gives the number of facets in this poset, whereas in Corollary 3, it is stated that if in Equation (35) it holds that then (35) has a solution based on the number of some Gelfand–Tsetlin patterns;

- Theorems 9 and 10 give properties of some Brauer configuration algebras and their mutations dealing with Gelfand–Tsetlin equations and some suitable variations;

- Theorem 13 describes the way that mutations of Brauer configuration algebras can be used to solve Diophantine problems of type ;

- As a consequence of Theorem 5, Corollary 4 describes some properties of the AES key schedule in terms of mutations of Brauer configurations.

Author Contributions

Investigation, A.M.C., I.D.M.G. and J.D.C.V.; Writing–review–editing, A.M.C. and I.D.M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Diophantine problem | |

| dimension of a Brauer configuration algebra | |

| dimension of the center of a Brauer configuration algebra | |

| path algebra | |

| Frobenius number | |

| general linear Lie algebra | |

| Gefand–Tsetlin equation | |

| hearts poset | |

| vertices in a Brauer configuration | |

| seed of a mutation | |

| message of a Brauer configuration | |

| number of occurrences of a vertex in a polygon V | |

| marked poset | |

| radical of an algebra | |

| Gelfand–Tsetlin numbers | |

| truncated vertices | |

| ordered sequence of polygons | |

| valency of a vertex | |

| word associated with a polygon of a Brauer configuration | |

| AES | Advanced encryption standard |

| CMP | Chicken McNugget problem |

| CCMP | Counter mode with CBC message authentication code protocol |

| DFA | Deterministic finite automaton |

| GT | Gelfand–Tsetlin |

| NFA | Non-deterministic finite automaton |

| PSK | Pre-shared key |

| TKIP | Temporal key integrity protocol |

| WPA | Wi-Fi protected access |

References

- Chapman, S.T.; O’Neill, C. Factoring in the Chicken McNugget monoid. Math. Mag. 2018, 91, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Loera, J. The many aspects of counting lattice points in polytopes. Math. Semesterber. 2005, 52, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvester, J.J. On the partition of numbers. Quart. J. Pure Appl. Math. 1857, 1, 141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Alfonsín, J.L. The Diophantine Frobenius Problem; Oxford Univ Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Euler, L. Introductio in Analysin Infinitorium; Krazer, A., Rudio, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1748. [Google Scholar]

- Euler, L. De partitione numerorum in partes tam numero quam specie dates. Novi Comentarii Academiae Scientiarum Imperialis Petropolitanae 1770, 14, 168–187. [Google Scholar]

- Futorny, V.; Grantcharov, D.; Ramirez, L.E. Irreducible Generic Gelfand-Tsetlin Modules of gl(n). Symmetry Integr. Geom. Methods Appl. SIGMA 2015, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, L.E. Combinatorics of irreducible Gelfand-Tsetlin sl(3)-modules. Algebra Discret. Math. 2012, 14, 276–296. [Google Scholar]

- Rosales, J.C.; García-Sánchez, P.A. Numerical Semigroups; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 20. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, J.B. Note on linear forms. Proc. Am. Soc. 1956, 7, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Alfonsín, J.L. Complexity of the Frobenius problem. Combinatorica 1996, 16, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assem, I.; Simson, D.; Skowronski, A. Elements of the Representation Theory of Associative Algebras: Techniques of Representation Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Struble, C. Analysis and Implementation of Algorithms for Noncommutative Algebra. Ph.D. Thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Green, E.L.; Schroll, S. Brauer configuration algebras: A generalization of Brauer graph algebras. Bull. Sci. Math. 2017, 141, 539–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañadas, A.M.; Espinosa, P.F.F. Homological ideals as Integer specializations of some Brauer configuration algebras. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.00050v1. [Google Scholar]

- Haugland, T. Decomposition of Modules over Finite-Dimensional Algebras. Master’s Thesis, NTNU, Trondheim, Norway, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- GAP. Mathematical Software. Available online: https://www.gap-system.org/Manuals/pkg/qpa/doc/chap4.html (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- SAGE. Mathematical Software. Available online: https://doc.sagemath.org/html/en/reference/quivers/sage/quivers/algebra.html (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Sierra, A. The dimension of the center of a Brauer configuration algebra. J. Algebra 2018, 510, 289–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, P.F.F. Categorification of Integer Sequences and Its Applications. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rutten, J.; Ballester-Bolinches, A.; Llópez, E.C. Varieties and covarieties of languages. ENTCS 2013, 298, 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rees, S. The Automata that define Representations of monomial algebras. Algebr. Represent. Theory 2008, 11, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, I. Refined enumerations of alternating sign matrices: Monotone (d,m)-trapezoids with prescribed top and bottom row. J. Algebr. Comb. 2011, 33, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, I. Sequences of labeled trees related to Gelfand-Tsetlin patterns. Adv. Appl. Math. 2012, 49, 165–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zeilberger, D. Proof of the refined alternating sign matrix conjecture. N. Y. J. Math. 1996, 2, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fourier, G. Marked poset polytopes: Minkowski sums, indecomposables, and unimodular equivalence. J. Pure Appl. Algebra 2016, 220, 606–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinson, D.R.; Paterson, M.B. Cryptography: Theory and Practice, 4th ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).