Abstract

In this paper, we study the dynamics of a fractional-order epidemic model with general nonlinear incidence rate functionals and time-delay. We investigate the local and global stability of the steady-states. We deduce the basic reproductive threshold parameter, so that if , the disease-free steady-state is locally and globally asymptotically stable. However, for , there exists a positive (endemic) steady-state which is locally and globally asymptotically stable. A Holling type III response function is considered in the numerical simulations to illustrate the effectiveness of the theoretical results.

1. Introduction

The study of the spread of disease is one of the main directions of mathematical modeling. There has been enormous effort to study the dynamics of infectious disease and various generalizations of the epidemic models that exist in the literature. More recently, there has been an increasing interest in epidemic models that involve time-delays and fractional-order derivatives [1,2,3,4,5]. The need for fractional-order differential equations (FODE) comes from real-world application problems. These equations are generalizations of ordinary differential equations and believed to take their origin from the question of L’Hopital to Leibniz in a report letter at the end of the 17th century [6]. Many famous mathematicians, such as Liouville, Riemann, Fourier, and Abel contributed to the Theory of Fractional Calculus. FODE models have advantages over classical ODE and/or delay differential equation models, since integer-order derivatives are used to gain information only about local features of a state, whereas fractional-order derivatives describe the whole space [7]. In other words, in the FODE models, the next certain position for a physical phenomenon does not only depend on the current state, but also on all historical states. Thus, fractional-order models not only give more realistic biological models involving memory, but also enlarge the stability region of the states. It is worth mentioning that FODEs have been successfully applied to various fields, such as finance [8], control theory [9], ecology [10], and medicine [11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

Incidence rate refers to the frequency with which a disease occurs over a specified period of time. It is numerically defined as the number of new cases of a disease within a time period, as a proportion of the number of people at risk for the disease. This rate provides the capacity to anticipate future incidents and plan accordingly. Thus, the incidence rate function type plays a key role in understanding the dynamics of infectious diseases. However, in most cases, it has been observed that the incidence rate starts to slow down after some time. In the last few decades, there have been studies considering nonlinear incidence rates given by a general function which satisfies certain mild conditions [18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. On the other hand, there are fractional-order epidemic models with a bilinear incidence rate and standard incidence rate, as well as specific nonlinear incidence-rate functions [5,16,25,26,27]. However, these models need to be modified by means of the general incidence-rate function. More recently, the authors in [26] considered a fractional-order Susceptible-Exposed-Infected-Recovered (SEIR) model with a generalized incidence rate function of the type , where f satisfies some certain conditions. Furthermore, Lahrouz et al. studied a fractional-order Susceptible-Infected-Recovered (SIR) model with a general incidence rate function and carried out Mittag–Leffler stability and bifurcation analysis for the model with and without delays [24]. It should be noted that the authors considered the model with a delay on the recovered/removed population () and investigated the global dynamics.

In the modeling of infectious diseases, it is assumed that there exists a latent period before an infected individual becomes infectious. In other words, it takes some time for an infected person to be able to transmit a disease to another susceptible host. This time-interval is called the latency period, and is modeled by delay differential equations. There are many interesting papers which study epidemic models with a constant delay in integer-order [28,29] and fractional-order differentiation [7,30].

Historically, the study of a so-called Susceptible-Infected-Recovered (SIR) model goes back to the work by Kermack and McKendrick [31]. Since then, this model has been widely studied to predict the dynamics of different infectious diseases. In the present paper, we introduce the fractional-order SIR model with a general incidence rate and time-delay. In Section 2, we provide the epidemic model and in Section 3, we study the local stability of the steady-states. In Section 4, we discuss the global stability of the endemic model. In Section 5, we display some numerical simulations, and then we conclude in Section 6.

Some preliminaries and definitions about fractional-order derivatives are given in the Appendix A.

2. Fractional Epidemic Model with a General Incidence Rate

Consider a system of delay differential equations for an SIR model

is the recruitment rate, is the natural death rate, is the recovery rate, is the disease-induced death rate, and is the delay due to the latency period. We assume the nonlinear incidence rate function satisfies the following conditions:

- (A1)

- ;

- (A2)

- is always positive, continuous, differentiable, and monotonically increasing:

- (A3)

- is concave with respect to I:

One can easily check that the following incidence-rate functions satisfy the conditions (A1)–(A3):

In this paper, we do not consider a specific incidence rate function, but a general one that satisfies mild conditions. Consequently, the results of this paper can be applied with any incidence rate function that satisfies the conditions (A1)–(A3). In Section 5, we implement the theoretical results with a Holling type III functional response, that is, .

After integrating from to t, the model (1) reads as

where the constant kernel function K satisfies . For some biological systems, fractional differential equations are more consistent with real phenomena than integer-order models. This is because fractional derivatives and integrals can be used to describe the memory and hereditary properties. In order to consider the historical effects in the above system, we modify the kernel function K as follows:

where and is the Gamma function, as specified in Appendix A. Introducing a power-law memory kernel function that allows near-past events to have a greater effect on the model than distant past events, by Definition A1, the modified model now reads as:

By applying Lemma A1, see Appendix A, the last model is equivalent to the following SIR model:

with initial conditions , , , , and is a smooth function.

The fractional derivative is defined by the Caputo sense, so introducing a convolution integral with a power-law memory kernel (3) benefits in describing memory effects in dynamical systems. The decaying rate of the memory kernel depends on . A lower value of corresponding to more slowly-decaying time-correlation functions leads a long memory. Therefore, as , the influence of memory decreases.

Under the condition (A1), it is easy to check that the model (5) has a disease-free steady-state solution . In the analysis of epidemic models, it is of utmost importance to find so-called basic reproductive numbers, which serves as a threshold value. We compute by using the next-generation matrix technique [32]:

The existence of a unique endemic steady-state solution usually depends on and satisfies the following algebraic equations:

The following lemma [23] ensures the uniqueness of the positive steady-state solution if .

3. Local Stability of the Epidemic Model

The corresponding linearized system of model (5) at any steady-state is described as

Taking the Laplace transform on both sides of (8) yields

Here, , , are the Laplace transform of , , and with , and . The above Equation (9) can be written as

where

and

is the characteristic matrix for the system (8) at . The stability conditions are also related to the fractional-order .

Theorem 1.

The disease-free equilibrium point is locally asymptotically stable if

i.e., if

Proof.

The characteristic equation at is described by

- Case (i), when .

Therefore, the disease-free equilibrium point is locally asymptotically stable if or .

- Case (ii), when .

In this case, Equation (10) becomes

Put

Separate the real and imaginary parts of the above equation

If we square and add both sides, one can have

For , it has been shown in [34] that the steady-state is locally asymptotically stable if all the eigenvalues satisfy the condition . The fractional order enlarges the stability region of the solution of the model.

Next, we discuss the local stability at an endemic equilibrium point , at which the characteristic equation is

Therefore,

Theorem 2.

Let , then the interior equilibrium point is locally asymptotically stable for if the following conditions are satisfied

- (i)

- (or)

- (ii)

Proof.

Case (i) Equation (13) becomes

Based on [35], the point is asymptotically stable if the following hold:

- (i)

- (or)

- (ii)

Holling Type III Functional Response

In this subsection, we consider the system (5) in the case with the Holling type III functional response. That is, we take as an incidence rate function. We derive the linearized system, and applying the Laplace transform, one can finally get the following characteristic matrix at ,

Theorem 3.

The disease-free equilibrium point is locally asymptotically stable if

Proof.

The characteristic equation at is described by

- Case (i) when .

Therefore, the disease-free equilibrium point is locally asymptotically stable if

- Case(ii) When .

In this case, Equation (14) becomes

Put

Separate the real and imaginary parts of the above equation

If we square and add both sides, one can have

The local stability at an endemic equilibrium point for this case, follows the same proof of Theorem 2.

4. Global Stability Analysis

Now, we study the global stability of the infection-free and endemic steady-states using a certain Lyapunov functional. Summing all equations in (5) yields

One can easily show that the last inequality implies that

where is the standard Mittag–Leffler function, see Appendix A for the definition. The last inequality implies that if , then . In other words, the region

is a positively invariant set of the system (5). Thus, we consider the model (5) in a biologically feasible region .

Theorem 4.

Assume that (A1)–(A3) hold and . Then, the disease-free steady-state solution is globally asymptotically stable.

Proof.

Let us consider the following Lyapunov functional:

Note that and since Further, since it follows that Thus, is positive-definite. Differentiating in fractional-order along the trajectories of (5) yields:

By theorem hypotheses, and from the monotonicity of with respect to S, we have

The concavity of with respect to I leads to , and hence we have

Therefore,

Thus, for all . On the other hand, one can show that the largest invariant set of is the singleton , that is, the disease-free steady-state solution. Thus, by the Lyapunov–Lasalle theorem for FODE (Lemma 4.6 in [11]), we conclude that is globally asymptotically stable. This finalizes the proof. □

In what follows, the auxiliary lemma on the estimate of a Volterra-type Lyapunov function will be useful to prove the global stability of the endemic steady-state solution.

Lemma 2.

[4] Suppose that is a differentiable function in the Caputo sense. Then,

for and

To carry out further stability analysis, we need the following condition:

- (A4)

Theorem 5.

Assume that (A1)−(A4) hold and . Then, the endemic positive equilibrium state is globally asymptotically stable.

Consider the following Lyapunov function: + Note that , and since is a Volterra-type Lyapunov function for any . Due to monotonicity of the function , we have if and if . In either case, one can show that Thus, is a Lyapunov functional. Differentiating in fractional-order along the trajectories of (5) and implementing Lemma 2 together with (7) yields

After factoring the last term of the above expression, we obtain

Due to the monotonicity of with respect to S, we have

Moreover, since is a Volterra-type Lyapunov function with , we have Thus, the second, third, and fourth lines in (17) are non-positive. Finally, the condition (A4) implies that

Hence, holds for , since and are positive numbers. Thus, by the similar arguments as in Theorem 4, we conclude that is globally asymptotically stable. □

5. Numerical Simulations

To illustrate the theoretical results obtained in the previous sections, we provide a numerical scheme for finding the solution of the fractional-order ODEs. To this end, we follow the modified Adams—Bashforth—Moulton method which has proven to be an effective tool to numerically solve fractional-order delay differential equations [5,7,9]. Let us highlight the main features of the algorithm of the modified Adams—Bashforth—Moulton method. In this regard, consider the following fractional-order delay differential equation.

where and is a Lipschitz-continuous function. This initial value problem is equivalent to the following Volterra-integral equation

For given mesh points, with step-size such that and let and for . Assume further that are calculated for . Then the numerical scheme for the integral Equation (19) is given by

Next, we consider the nodes with the weight function and apply the product trapezoidal quadrature formula to approximate the integral of (20) on the right-hand side.

where

Hence, we can formulate the numerical scheme for the IVP (18) as follows.

The term is approximated by the so-called predictor, , evaluated by the product rectangle rule by means of the Equation (20).

where

For the simulation part, we use the algorithm (22) and Holling type III function, as an incidence rate response for the fractional-order SIR model (5). One can easily check that the conditions (A1)–(A3) are satisfied. Thus, by using the next-generation matrix technique, one can compute the basic reproduction number as . Thus, let us write the numerical scheme (22) for the model (5) with Holling type III function:

where is defined as before.

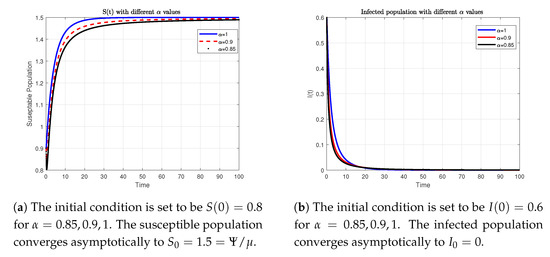

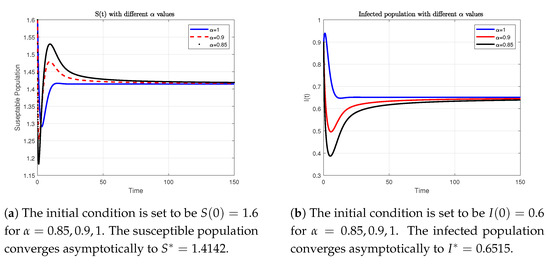

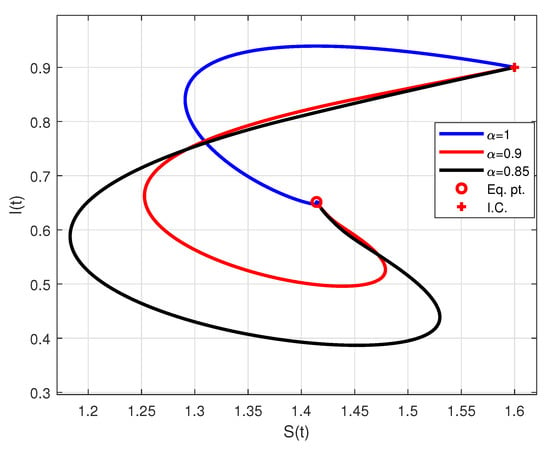

In what follows, we use different values of and the parameters to show the effectiveness of the theoretical results obtained in Theorems 4 and 5. For the choice of the parameters , , , , , , and we have . The numerical simulations in Figure 1 reveal that the susceptible population asymptotically converges to , whereas the infected population asymptotically converges to for . Thus, the disease-free steady-state solution is asymptotically stable. Hence, the numerical simulations support the theoretical result obtained in Theorem 4. On the other hand, for the choice of the parameters , , , , , , and , one can show that and there exists a positive steady-state solution . The numerical simulations in Figure 2 and Figure 3 reveal that the susceptible population asymptotically converges to , whereas the infected population asymptotically converges to for . Thus, the endemic steady-state solution is asymptotically stable. Hence, the numerical simulations support the theoretical result obtained in Theorem 5.

Figure 1.

Numerical simulations of the model (5) with different values and the Holling type III function response. For the set of parameters and we have . Thus, the endemic steady-state solution is asymptotically stable.

Figure 2.

Numerical simulations of the model (5) with different values and the Holling type III function response. For the set of parameters and we have . Thus, the disease-free steady-state solution is asymptotically stable.

Figure 3.

Phase portrait of the model (5) with different values, the Holling type III function response and the set of parameters and . The solutions with the initial condition (I.C.) converges asymptotically to the endemic steady-state solution .

6. Concluding Remarks

In the present paper, we studied local and global stability analyses of the delayed fractional-order SIR epidemic model with a general incidence rate function that satisfies some mild conditions. The fractional derivative is considered in the Caputo sense, which is suitable for initial-value problems. The disease-free steady-state solution of the underlying model is locally and globally asymptotically stable when , whereas when , there exists a positive endemic steady-state solution which is locally and globally asymptotically stable. To illustrate our theoretical results, we considered the Hooling type III functional response as the incidence-rate function and used the modified Adams—Bashforth—Moulton method to simulate an example. Fractional-order differential equations are at least as stable as their integer-order counterparts. Further, the presence of a fractional differential order and time-delay in a differential equation can result in a significant increase in the complexity of the observed behavior, and the solution continuously depends on the previous states.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.; formal analysis, F.A.R. writing-review, F.A.R.; methodology, F.A.R.; writing-original draft, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the research grant No. AP08052345 “Mathematical models for glioblastoma proliferation” from the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

Acknowledgments

A.K. would like to thank the Department of Mathematical Sciences at UAE University for their hospitality as well as the Asian Universities Alliance (AUA) for their support of this trip. The authors thank the editor, C.Rajivganthi, and reviewers for their valuable comments which improved the quality of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

We briefly give the definitions that play an important role in the theory of fractional-order ordinary differential equations (FODE). The Gamma function is given by and the standard Mittag–Leffler function is given by where

Definition A1.

[6] The Riemann–Liouville integral operator of order α is given by

Although the fractional-order integral is known by the previous definition, there are many notions of fractional derivatives. Due to its advantage in application to various fields and in particular to initial value problems in this study we use the definition by Caputo.

Definition A2.

[6] The Caputo fractional derivative of order of a function is defined by i.e.,

where

To make the manuscript self-contained we summarize the properties of fractional calculus in the following lemma.

Lemma A1.

For we have

References

- Rihan, F.A. Delay Differential Equations and Applications to Biology; Springer: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Atangana, A.; Araz, S.I. Nonlinear equations with global differential and integral operators: Existence, uniqueness with application to epidemiology. Res. Phys. 2021, 20, 103593. [Google Scholar]

- Atangana, A.; Qureshi, S. Mathematical Modeling of an Autonomous Nonlinear Dynamical System for Malaria Transmission Using Caputo Derivative. In Fractional Order Analysis; Dutta, H., Akdemir, A.O., Atangana, A., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-De-León, C. Volterra-type Lyapunov functions for fractional-order epidemic systems. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2015, 24, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diethelm, K.; Ford, N.; Freed, A. A Predictor-Corrector Approach for the Numerical Solution of Fractional Differential Equations. Nonlinear Dyn. 2002, 29, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlubny, I. Fractional Differential Equations; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rihan, F.; Al-Mdallal, Q.; Alsakaji, H.; Hashish, A. A fractional-order epidemic model with time-delay and nonlinear incidence rate. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2019, 126, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atangana, A.; Khan, M.A. Fatmawati Modeling and analysis of competition model of bank data with fractal-fractional Caputo-Fabrizio operator. Alex. Eng. J. 2020, 59, 1985–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Wen, G.; Rahmani, A.; Yu, Y. Distributed formation control of fractional-order multi-agent systems with absolute damping and communication delay. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2015, 46, 2380–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajivganthi, C.; Rihan, F.A. Stability of fractional-order prey-predator system with time-delay and Monod-Haldane functional response. Nonlinear Dyn. 2018, 92, 1637–1648. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, L. The effect of vaccines on backward bifurcation in a fractional-order HIV model. Nonlinear Anal. Realworld Appl. 2015, 26, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latha, V.P.; Rihan, F.A.; Rakkiyappan, R.; Velmurugan, G. A fractional-order model for Ebola virus infection with delayed immune response on heterogeneous complex networks. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2018, 339, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latha, V.P.; Rihan, F.A.; Rakkiyappan, R.; Velmurugan, G. A fractional-order delay differential model for Ebola infection and CD8+ T-cells response: Stability analysis and Hopf bifurcation. Int. J. Biomath. 2017, 10, 1750111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrak, O.O.; Mizrak, C.; Kashkynabayev, A.; Kuang, Y. The Impact of Fractional Differentiation in Terms of Fitting for a Prostate Cancer Model Under Intermittent Androgen Suppression Therapy. In Mathematical Modelling in Health, Social and Applied Sciences (2020), Forum for Interdisciplinary Mathematics; Dutta, H., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mizrak, O.O.; Mizrak, C.; Kashkynbayev, A.; Kuang, Y. Can fractional differentiation improve stability results and data fitting ability of a prostate cancer model under intermittent androgen suppression therapy? Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 131, 109529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. Stability of a Fractional-Order Epidemic Model with Nonlinear Incidences and Treatment Rates. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. A Sci. 2020, 44, 1505–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Atangana, A. A numerical study of the nonlinear fractional mathematical model of tumor cells in presence of chemotherapeutic treatment. Int. J. Biomath. 2020, 13, 2050021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashkynbayev, A.; Koptleuova, D. Global dynamics of tick-borne diseases. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2020, 17, 4064–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobeinikov, A. Lyapunov Functions and Global Stability for SIR and SIRS Epidemiological Models with Non-Linear Transmission. Bull. Math. Biol. 2006, 68, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korobeinikov, A. Global Properties of Infectious Disease Models with Nonlinear Incidence. Bull. Math. Biol. 2007, 69, 1871–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korobeinikov, A. Global asymptotic properties of virus dynamics models with dose-dependent parasite reproduction and virulence and non-linear incidence rate. Math. Med. Biol. 2009, 26, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maini, P.K.; Korobeinikov, A. A Lyapunov function and global properties for SIR and SEIR epidemiological models with nonlinear incidence. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2004, 1, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korobeinikov, A.; Maini, P.K. Non-linear incidence and stability of infectious disease models. Math. Med. Biol. 2005, 22, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lahrouz, A.; Hajjami, R.; Jarroudi, M.E.; Settati, A. Mittag-Leffler stability and bifurcation of a nonlinear fractional model with relapse. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2021, 386, 113247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouaouine, A.; Boukhouima, A.; Hattaf, K.; Yousfi, N. A fractional-order SIR epidemic model with nonlinear incidence rate. Adv. Differ. Equations 2018, 2018, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Ullah, S.; Ullah, S.; Farhan, M. fractional-order SEIR model with generalized incidence rate. AIMS Math. 2020, 5, 2843–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sene, N. SIR epidemic model with Mittag–Leffler fractional derivative. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 137, 109833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Huang, G.; Ma, W.; Takeuchi, Y. Global stability for delay SIR and SEIR epidemic models with nonlinear incidence rate. Bull. Math. Biol. 2010, 72, 1192–1207. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Takeuchi, Y. Global analysis on delay epidemiological dynamic models with nonlinear incidence. J. Math. Biol. 2010, 63, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vyasarayani, C.; Chatterjee, A. New approximations, and policy implications, from a delayed dynamic model of a fast pandemic. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2020, 414, 132701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kermack, W.O.; McKendrick, A.G. A contribution to the mathematical theory of epidemics. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1927, 115, 700–721. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Driessche Driessche, P.; Watmough, J. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Math. Biosci. 2002, 180, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Li, C.; Lü, J. Stability analysis of linear fractional differential system with multiple time delays. Nonlinear Dyn. 2007, 48, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihan, F.A.; Baleanu, D.; Lakshmanan, S.; Rakkiyappan, R. On Fractional SIRC Model withSalmonellaBacterial Infection. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2014, 2014, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmed, E.; Elgazzar, A. On fractional-order differential equations model for nonlocal epidemics. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2007, 379, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).