Abstract

Rising political and economic uncertainty over the world affects all participants on different markets, including stock markets. Recent research has shown that these effects are significant and should not be ignored. This paper estimates the spillover effects of shocks in the economic policy uncertainty (EPU) index and stock market returns and risks for selected Central and Eastern European markets (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Croatia, Slovakia and Slovenia). Based on rolling estimations of the vector autoregression (VAR) model and the Spillover Indices, detailed insights are obtained on the sources of shock spillovers between the variables in the system. Recommendations are given based on the results both for policymakers and international investors. The contribution of the paper consists of the dynamic estimation approach, alongside allowing for the feedback relationship between the variables of interest, as well as examining the mentioned spillovers for the first time for majority of the observed countries.

1. Introduction

The traditional asset pricing models developed in the last couple of decades include risk factors such as the market risk, value, size, momentum, and illiquidity as the mostly popular and used ones ([1,2,3,4,5]). Macroeconomic factors have been included over the years as well (see [6,7,8]). Nevertheless, economic policy uncertainty has gotten attention recently once again. This is especially true after the global financial crisis in the late 2000s. The researchers in [9,10] have developed the EPU (economic policy uncertainty) index, which is based on newspaper coverage of policy-related economic uncertainty. Ever since, there has been a growing bulk of literature which utilizes the EPU variable in explaining asset risk-return relationship ([11,12,13,14,15,16], etc.) which finds significant results—investors seek higher return due to economic policy uncertainty risk premium. Moreover, increases in EPU are related to stock return decrease and volatility increase ([13,17,18,19]).

The importance of examining such a topic has been in the literature since the 1970s, with Merton’s [20] inter-temporal asset pricing model. Here, it is assumed that investors hedge against shortfalls in consumption, i.e., there is a willingness to hold stocks with higher inter-temporal correlation with economic uncertainty in a portfolio. This is due to higher returns of such stocks when the economic uncertainty rises. Economic activity response to uncertainty has been examined in macroeconomic research as well since 1980s. The research of [21,22,23,24] are some of the prominent papers within this field. However, as mentioned previously, the last couple of years have experienced a rise of attention towards the consequences of uncertainty on financial markets. This is not only true within the academic research, but major international institutions recognize this as well (see [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]).

Since the uncertainty has many effects on the whole economy, it represents an important task to evaluate those effects, their sources, and significance in different sectors of the economy. Moreover, the effects of EPU could lead to recessions [12]. Existing research which focuses on financial and stock markets analyzes most developed markets and countries. There is less research regarding EPU and its interactions with selected variables on developing stock markets compared to more developed ones, which will be in the center of this study: selected Central and Eastern European (CEE) markets. Reasoning on why not much work has been done on CEE markets is due to lower liquidity [34] and not being important to domestic investors [35]. In this context, the purpose of this paper is to analyze the effect of EPU on stock market returns and risks; on the stock markets of Lithuania, Slovenia, Estonia, Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, and Croatia. The study utilizes monthly data (with different periods concerning each country), by estimating the VAR (vector autoregression) model and its extension with the [36,37] spillover index. The spillover index calculates the fraction of the h-step error variance of variables in the VAR model which are results of the shocks in any of the variables in the model, in the total forecast error variations. Thus, this paper belongs to the strand of research based on [17,38] model in which the government policies are modelled as a source of economic uncertainty which affects the equity prices and risk premium.

The main contributions of the paper are as follows: first, the research observes a dynamic approach of the spillovers between EPU, return, and risk on selected CEE stock markets. This enables to analyze changes over time with respect to different economic and stock market conditions. Put differently, the dynamic analysis consists of estimating a rolling window model which enables to capture changes in estimated parameters and spillovers over time. Second, the gap in the literature is filled by observing stock markets which are under-analyzed within this field. The CEE stock markets are less often analyzed in the related research compared to other more developed markets. This is especially true within the area of economic and political uncertainties and their interactions with the stock market. Thus, the results obtained could be helpful both for (potential) international investors and policy-makers within these countries. Accordingly, results and recommendations will be given based on different results. Third, a detailed analysis of all directional spillover effects is observed so that net emitters and net receivers of shocks in the model could be analyzed over time. In other words, the analysis in this paper enables the interpretations when the EPU index affects stock markets more and vice versa. Thus, the rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 gives an overview of related previous research. Section 3 describes the methodology used in Section 4. The final section, Section 5 concludes the paper with discussion.

2. Related Research Overview

Although the research on this topic is growing in the last couple of years, there are several common attributes in the majority of the work. Firstly, the majority of existing work focuses on most developed countries (USA, Germany, OECD countries in general), with little work found regarding less developed stock markets. Secondly, the methodological approach which is the most common is the VAR framework, sometimes ordinary regression analysis. Surprisingly, many papers do not include control variables in the study, which for sure could affect the results. Namely, not including country-specific (macro)economic specifics could result in spurious findings. Thirdly, a single-country approach is still the most common approach—meaning that the time-series approach is conducted most often. Next, return series are in the focus of the vast majority of papers, which means that EPU change effects are observed only in the return series. However, EPU affects the volatilities as well, as found in several papers. Thus, risk should not be ignored in research. Some newer research combines the regime-switching methodology in regression or VAR; the MGARCH (multivariate generalized autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity) or the MIDAS (mixed data sampling) approach. The rest of this section focuses on most recent findings regarding stock markets, with a brief overview of papers which utilize EPU variable within macroeconomic research.

Whether the changes in EPU affect stock markets of the European Union was analyzed in [39], with the inclusion of non-EU members in 2012: Croatia, Norway, Russia, Switzerland, Turkey, and Ukraine. The sample covered the period from January 1993 to April 2012 (monthly data). Using OLS (Ordinary Least Squares) regression, Sum (2012b) found that changes in EPU in Europe negatively affect all of the EU stock market returns with the exception of Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Other non-EU countries also were not affected by the EPU changes in the observed period. However, this research, as mentioned, utilized only OLS and without any control variables in the model. Thus, the results could be spurious. The same author [40] then utilized VAR methodology (with impulse response function and Granger causality testing) on the same two variables (return series and EPU changes) for the US data (period: 1985 to 2011). The conclusion was that stock returns mostly negatively respond to EPU shocks (in the majority of months in the IRF estimates). Again, no control variables were used in the study. The researchers of [38] are extensively focused on how government policy announcements impact stock market prices. The paper develops a theoretical model and use Bayesian modelling which showed that when the government announces its policy decisions, stock prices jump. The government can change or maintain its policy and the effect of its decision direction and size of the price jump. In addition, the price jumps depend on the extent to which this decision is unexpected. To conclude, [38] found that EPU is related to stock market volatility, correlations, and jumps. Monthly data for EPU and market indices for 11 economies (Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Russia, Spain, the UK, and the US) was collected in [41], from January 1998 to September 2014. Here, the link between EPU and stock prices was observed employing the coherency wavelet approach. The main result is that EPU and market indices have mostly negative relationship but during some periods, the relationship changes to a positive one (when changes occur from low to high-frequency cycles). How EPU can impact stock market volatility was investigated in [42] by using a heterogeneous autoregressive realized volatility model (from 2 January 1996 to 24 June 2013) for the S&P (Standard and Poor’s) 500 index. Rolling window analysis was applied and the sample was divided into sub-samples to see if EPU can predict stock market volatility. The results indicate that EPU and stock market volatility are connected with EPU having significant predictive power on stock market volatility. This was based on in- and out-of-sample prediction comparisons.

The relationship between EPU and stock market returns for China and India was tested in [43], using the bootstrap Granger full-sample causality test and sub-sample rolling window estimation. The sample included monthly data from February 1995 (2003) to February 2013 for China (India). On the one hand, there is no evidence of the relationship between the two observed variables for both markets, which is showed using the bootstrap full-sample causality test. On the other hand, the sub-sample rolling-window causality test found that there exists a bidirectional causal relationship between stock returns and movements in EPU for several sub-periods. To sum up, there is a weak relationship between EPU and stock market return in China and India. Again, the only observed variables in this study were the EPU index and the stock price. The aim of [44] was to construct uncertainty indices for the Euro area (EA) and individual EA-member countries. One of the conclusions of this paper is that uncertainty was high during the financial crisis in the EA, as well as during the European sovereign debt crisis. In addition, most European countries share a similar uncertainty cycle. The analysis showed how the spillover-effects between countries increase during the financial and European sovereign debt crises. Thus, it can be expected that similar conclusions could arise for CEE markets in this study. The researches in [45] wanted to explore whether EPU has an impact on the stock markets in the USA. To analyze this possible impact the regime-switching (RS) model was used. The sample consisted of monthly data for the US stock index and EPU index from 1900 to 2014. So much data enabled the utilization of the RS methodology to find business and stock market cycles. Three control variables were included in the study: changes in industrial production, default spread, and inflation. Results showed that the effect of policy uncertainty on the stock market is negative and weakly persistent. To enhance these findings, [45] employed a three-regime switching model. The model suggested that EPU affects differently stock market returns depending on market states. This means that EPU has a greater impact on stock returns during extreme volatility periods. A bootstrap panel Granger causality test was applied in [46] to observe the causal relationship between EPU and 9 stock markets (Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Spain, UK, and the USA) from January 2013 to December 2014. Findings in this paper indicate that there are some differences between countries: not all stock markets fall when negative EPUs arise. UK market was the most one to be affected by the EPU changes. Neutral results were found for Canada, China, France, Germany, and the USA. Researchers in [47] observed how the EPU affects stock markets in Australia, Canada, China, Japan, Korea, and the USA (monthly data, from January 1998 to December 2014). Here, the impact of the US and individual country’s EPU shocks was tested on all mentioned markets using panel VAR model and IRF (impulse response function). In the analysis, the growth rate of industrial production, CPI (consumer price index) inflation rate, short-term interest (policy) rate, and the nominal effective exchange rates as the control variables were included. Results indicated the existence of a connection between uncertainty and stock markets: negative impact of own country EPU shocks on stock returns. The same results are found for US shocks for all countries except Australia where the effect was positive. Researches in [48] focused on the causal relationship between economic policy uncertainty (EPU) and stock market prices for 14 OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries using the bootstrap panel Granger causality approach. To analyze the above-mentioned relationship, monthly data from March 2003 to April 2016 for the US, Japan, Germany, UK, France, Italy, Canada, South Korea, Australia, Spain, Netherlands, Sweden, Ireland, and Chile was used. The results suggested that the relationship between uncertainty and stock prices exists for all countries except Japan, Chile, and France.

The relationship between EPU and market volatility was examined in [49] in the long run for the UK and US markets. Moreover, a long-run correlation between these two markets was observed as well. The study covered the period from January 1997 to April 2016 and daily data for S&P500 and FTSE100 (Financial Times and the London Stock Exchange) indices, with monthly data for EPU-s. Using the two-step DCC-MIDAS (dynamic conditional correlation mixed sampling data) model, results indicated that the US long-run stock market volatility depends significantly on its own EPU shocks, while the UK long-run stock market volatility depends significantly on both countries’ EPU shocks. Researchers in [50] using VAR Granger-causality tests, IRFs, and variance decomposition analysis examined the relationship between EPU and stock market liquidity in India. The sample consisted of stocks that are listed on the National Stock Exchange (NSE) of India from the period of January 2013 to December 2016. The study used the stock price and several firm-specific variables. Rolling twelve-month reserve money growth rate, industrial production growth rate, inflation rate, and net funds flow from foreign institutional investors are used as macroeconomic control variables, while stock market volatility and stock market return were used as market-related control variables. The results showed that the relationship between EPU and stock market liquidity is significant. During normal market conditions, EPU influences stock market liquidity. On the other hand, IRFs showed negative effects of EPU on market liquidity which consequently strengthens the illiquidity of the stock market. Researchers in [51] focused on the UK stocks and applied the time-varying parameter factor-augmented VAR model. The domestic and international economic uncertainty variable was used in the model, by firstly constructing the uncertainty variable from the principal component analysis. For the period from January 1996 to December 2015, results indicate that the economic activity uncertainty and UK EPU explain the cross-section of UK stock returns. Such a study is important nowadays due to uncertainties that arise from the Brexit vote and political on goings.

The other group of papers that employ the EPU variable in the analysis is the one in which authors look at interactions of EPU with macroeconomic variables. Since this is not of interest in this study, just a brief overview is given regarding this group of research. Theoretical work ranges from EPU effects on output [52], investment [53] to trade [54], and capital flows [55].

The aim of [19] was to study the impact of EPU on the Indian economy (GDP growth, change in index of industrial production (IIP), change in fixed investment, and change in private consumption) in the period 2003–2012. The main conclusions include the existence of a negative correlation between the stock market index and EPU, as well as between the economic growth and uncertainty. To sum up, EPU significantly slows down investment in the country, industry, and firm levels. Researchers in [56] employed a heterogeneous panel structural VARs on many countries over the world (including Europe, China, Western Hemisphere countries) to see how EPUs from different countries spillover towards others. The majority of the data used was quarterly, with different periods ranging for different countries (from the first quarter of 1985 until the fourth quarter of 2016). The main results indicate that EPU reduces real output growth, private consumption, and investment. Major emitters of EPU shocks to others were the US, Europe, and China.

Based on the papers mentioned above, uncertainty presented through the EPU index mostly has an impact on stock returns and volatility. Additionally, there are other types of measuring uncertainty. For example, [57] used past data for the stock price and volume trading to predict future stock prices. More precisely, this paper aimed to perceive does the technical analysis work in Bulgarian Stock Market. Data used for the empirical part were daily data for the Bulgarian Stock Index from 21 November 2003, to 1 March 2018. For the observed period, they proved the existence of predictive power for technical analysis, meaning that uncertainty has an impact on stock prices. On the contrary, [58] used data from 4 March 2005, to 11 December 2015, for stocks that were listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange at the observed period. Using different econometric tests they concluded that technical analysis does not have predictive power on Romanian Stock Market. Daily data for the Dow Jones Emerging Markets Index from 31 December 1991 to 30 December 2011 was employed in [59]. Based on out-of-sample analysis technical analysis has strong predictive power on short-term returns in emerging markets. Technical analysis was tested for 23 emerging markets in the paper by [60], where data for Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) Emerging Market Index (EMI) was used, which reflects equity indices for emerging markets for the period from 1 January 1988, to 5 May 2017. Results showed a strong predictive power of technical analysis for future prices of stocks. To sum up, [60] concludes that the majority of researches support the predictive power of technical analysis.

As can be seen in this overview, less work is done on CEE markets (financial markets and the economy as a whole). Obtaining more information on this subject on the CEE markets can enable policymakers to enhance the development of these markets. This would make the CEE markets more attractive to international investors.

3. Methodology Description

This section describes the basics of the used methodology, namely the VAR model and its extension, the [36,37,61] spillover index. More insights can be obtained in the mentioned papers, and the following ones: [62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. A stabile VAR(p) model with N variables is observed in a compact form as follows:

where Yt denotes the vector consisting of vectors yt of variables in the model, a = [v 0 … 0], where v is the vector of constants, A = and εt is the innovation vector, with properties E() = 0; E( ) = Σε < ∞; E( ) = 0 for t ≠ s. The impulse response functions (IRFs) are estimated based on the MA(∞) representation of model (1), given in the form:

i.e., in the polynomial form:

where Φ(L) denotes the polynomial of the lag operator L, containing impulse response coefficients. Due to innovation terms in being correlated, the variance-covariance matrix Σε is either ortogonalized via Choleski decomposition or the GFEVD approach (generalized forecast error variance decomposition) is utilized. The latter approach does not depend on variable ordering in the system. This paper utilizes the GFEVD approach in estimation.

Yt = a + AYt−1 + εt,

The forecast error of the h steps ahead is estimated as the difference between the actual and expected values: et+h = Yt+h − E(Yt+h). The mean squared error is then estimated for every element in et+h as the following expected value: E(yj,t+h − E(yj,t+h))2. Next, the variance (mean squared error) is decomposed into shares of shocks in every variable in the model, as follows:

Thus, values in (4) represent the share of variance of variable j in the h step ahead forecast which is due to shocks in variable k. ej and ek are the unit vectors from the matrix INp. Now, the Diebold and Yilmaz [36,37,61] spillover index (SI) is the following ratio:

where the numerator represents the sum of all shares in variances of the variables in the model, and the denominator represents the total forecast variance. Besides the total spillover in (5), the indices “from” and “to” spillovers are estimated to distinguish which variable in the model is the emitter of shocks and which is the receiver. The “from” SI is calculated via the formula:

whilst the “to” index is estimated as:

The net spillover index can be calculated as well as the difference between the two mentioned indices. Bivariate spillover indices can be estimated as well to see all possible pairs of spillovers between variables in the VAR model. Finally, the dynamic approach is often employed to evaluate spillovers over time and the changes of directions between them. This will be employed in this study as well, by estimating rolling SIs.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Variable Description

For the empirical analysis, monthly data on the EPU Europe index was collected from [69] website for the following countries: Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Croatia, Slovakia, and Slovenia. The European level of EPU was downloaded due to individual country level EPU not being available for the CEE countries in the study. The time span for every country differs, due to data availability of other variables in the system. Moreover, previous research has shown that the world and European uncertainty affect the CEE economies in a great way (e.g., Lithuania 92.5%, and other results in [70]). Details are shown in Table A1 in the Appendix A. The EPU index used in the study is the [10] construction based on media coverage, disagreements among economic forecasters, and tax expiration codes. Moreover, for individual country-level specifics, monthly data from [71] on the following macroeconomic variables were collected as control variables: CPI (consumer price index, i.e., HICP, 2015 = 100), IIP (index of industrial production, 2015 = 100), Irate (interest rate, short term, REER (real effective exchange rate, index, 2010 = 100) and Unemp (unemployment rate, monthly average). All of the variables are seasonally adjusted. From the website [72] daily data on stock market indices were collected and daily return series were calculated. Based on the daily data, average monthly returns and standard deviations were calculated for the return and risk series.

Before the analysis, the unit root tests (ADF, augmented Dickey–Fuller (based on the recommendation of the reviewer, the KPSS (Kwiatkowski–Phillips–Schmidt–Shin) unit root test was performed as well. The results are omitted from the paper, but are available upon request. The results indicate the same conclusions as the ADF tests did) were performed on all monthly variables, with results shown in Table 1 (constant was included as a deterministic regressor). Those variables which were found to be non-stationary in levels (e.g., Irate for Estonia, Lithuania, etc.) were differenced and the test showed that the differenced values were stationary (see Table A2 in Appendix A). Thus, all stationary variables are used further in the analysis. The risk, return and EPU series are observed as endogenous in the model, whilst the rest of the macroeconomic variables are used as exogenous (i.e., control variables). Descriptive statistics for all stationary variables is given in Table A3 in Appendix A.

Table 1.

Unit root test results, variables in levels.

4.2. Initial Results

To estimate a VAR(p) model for every country, the information criteria were calculated based on the VAR model by re-estimating it for lags p from 1 to 12. The best lag based on each criterion is shown in Table 2. Since not all criteria indicated the same lag length for a country, the VAR model was estimated from the lowest lag length, multivariate tests of autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity have been performed and the lag length was increased until the null hypothesis for both tests could not be rejected. The chosen lags for every country are given in the last column (labelled “chosen”) in Table 2. Thus, length of one month was chosen for Bulgaria, Czech Republic and Slovakia, two months for Poland, three months for Slovenia, seven months for Croatia, nine months for Estonia and 13 months for Lithuania.

Table 2.

Optimal lag value for vector autoregression (VAR) model, different criteria.

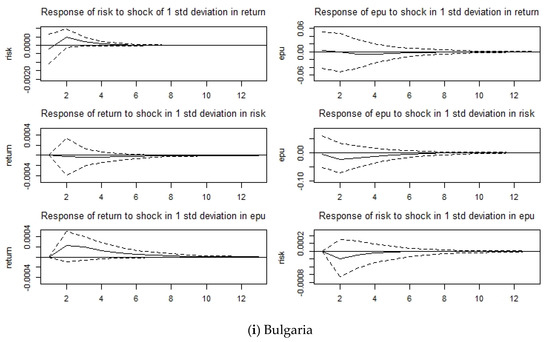

The impulse response functions for every country’s respective VAR model are shown in Figure A1a–i in the Appendix A. Since the VAR model and the IRFs were estimated based on the whole sample for every country, these could be observed as the static approach. The IRFs were constructed based on the 12 month forecast horizon, with 95% confidence intervals. Every figure indicates the impulse responses over time, i.e., how a variable within the VAR model reacts to shocks of one standard deviation in other variables in the model. The majority of the focus is on looking at the effects of EPU changes on the other two variables, the majority of interpretations are given for these cases. As Figure A1 shows, shocks in the EPU variable have little to no effects on return and risk series for almost every country: the effects on both variables are non-existing for Slovakia; the risk is not affected for Lithuania, Croatia, Poland, Estonia, Czech Republic, and Bulgaria. This conclusion is due to the null values of effects being present in the 95% confidence intervals, meaning that no effects were present in the mentioned intervals. Such results could be surprising at first glance. However, as [73] explain, based on their theoretical model developed in [17], stock prices respond to political signals, but interacted with the preciseness of such signals. If there exist many signals coming from politics and economics, but with varying quality, the results are that stock prices will not react at all. Moreover, lower volatility as a result of higher EPU could be, again due to imprecise political signals [73], which could explain the only significant effects on risk are found for Hungary, which is negative for the first several months. By focusing on the return reactions, there are only short-term effects on return reduction of Lithuania (one month), Croatia and Estonia (both two months) and Bulgaria (three months). These significant findings are in line with [74], in which EPU has negative effects on equity prices—by raising the risk premium. Positive reactions of return series are found for Poland and the Czech Republic (two months). Hungarian return series did not react at all.

By switching to EPU reactions to shocks in Return and Risk series, Figure A1 indicates that shocks in the return series result in a decrease of EPU for the Czech Republic and Croatia for one month, Bulgaria, Slovenia and Slovakia for two months, Estonia three months and Lithuania for twelve months. No reactions were found for Poland and Hungary. Shocks in the risk series do not affect the EPU series. The only exception is Slovenian risk, which affects the EPU series from with a lag of four months onwards. These findings indicate that CEE risk and return series have little effects on the EPU series. The majority of previous work finds that CEE stock markets are the receivers of return and risk spillovers from other more developed ones [75,76,77,78].

Next, the total spillover indices (SI) have been estimated for every country, alongside directional indices and are given in spillover tables in Table 3 (a)–(i). The spillovers have been estimated based on the forecast horizon of 24 months for the majority of the countries, with 36 months for Slovenia, Croatia, Lithuania, and Estonia. The 24 months is chosen so that potential lagged effects of shock spillovers can be captured and the 36 months was used in countries that have the most data available. Bolded values in the bottom right corner of each table are the total SIs for the whole time sample of each country. Greater spillovers between the EPU, Risk, and Return series are found for the Czech Republic, Lithuania, Slovenia, and Poland, which means that mentioned countries experience greatest spillovers of shocks between the three observed variables, i.e., greatest connectedness is found between individual country return, risk, and EPU from Europe. Reasoning on such results could be found in the size of the stock markets of mentioned countries (in terms of market capitalization, especially Poland), best market development, and lowest industry concentration (see [79]). Moreover, the mentioned markets are connected with Western European markets with spillover effects coming from Western Europe to the mentioned CEEs found in [80]. By being more connected to the rest of Europe and especially those countries that are generators of economic and policy uncertainty in Europe, it is not surprising that those countries have stronger reactions of risks and returns when EPU shocks occur. Moreover, the Lithuanian economy openness is another reason on why its market is more strongly affected by the European EPU (see [81]).

Table 3.

Spillover tables for every country, full sample.

By observing the cells in which the total variance of each variable is explained by the shocks in EPU (e.g., for Bulgaria it is the value of 3.30%—meaning that shocks in EPU explain 3.30% of the total variance of variable Return), it can be seen that the greatest spillovers of shocks from EPU to return series are for Czech Republic, Estonia, Lithuania, Croatia, and Slovenia. Only one country experienced greater spillover from EPU to risk (Estonia with 14.76%). These findings are in line with [82], in which greater spillovers in the mean series were found when compared to volatility series (via a nonparametric approach of testing causality-in-mean and causality-in-variance). The lowest spillovers from EPU to risk and return series are found for Bulgaria (0.69% and 3.30% respectively), which indicates that outside European EPU shocks have the least effects on the Bulgarian stock market. These results are in line with [83], in which the systematic shocks were found to be non-significant for the Bulgarian market, and conclusions indicated that this country should focus more on country-specific shocks. EPU variable as a receiver of shocks in Table 3 mostly is affected by the return series of Czech Republic, Estonia, Slovenia, Slovakia, and Lithuania; and the risk series of Estonia. Although the EPU index is constructed based on newspaper articles on politics and economics, the result of EPU being affected by shocks in return and risk series of the mentioned markets is in line with results of [84], who found that the European EPU is influenced by high and low systematic risk in emerging markets.

As an additional checking on which variable within the model is the causal one, the Granger causality test was performed for the whole sample. Results are given in Table 4, where the EPU causes the other two variables for the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Croatia, and Slovenia. This confirms the previous comments on the total SIs for the mentioned countries. Similar conclusions can be obtained by comparing the values of spillover indices from Return and Risk series to others in Table 3 with the rest of the results in Table 4.

Table 4.

Granger causality test results.

4.3. Dynamic Results

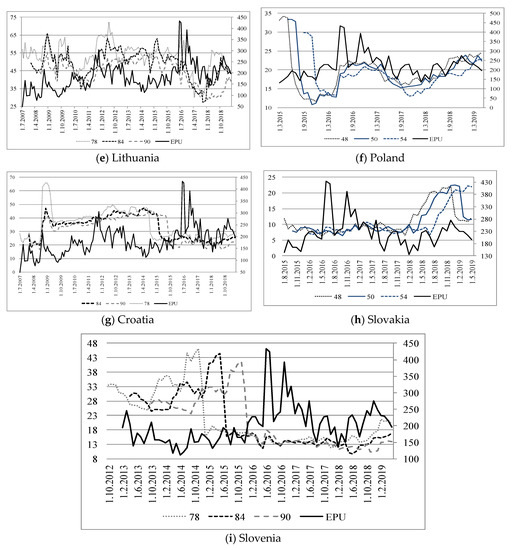

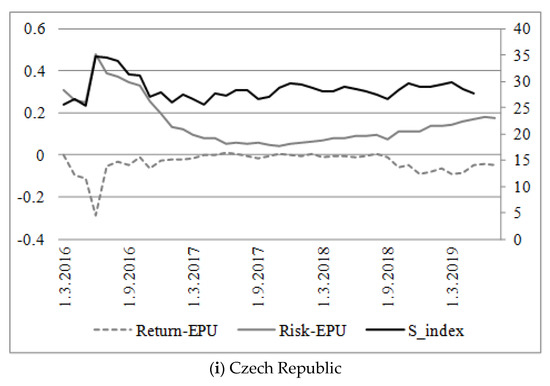

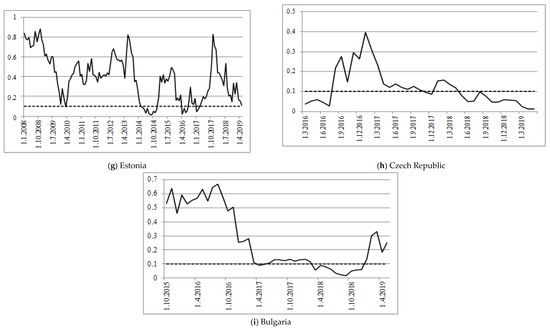

The previous analysis was based on the whole sample estimation. This section focuses on the results of the dynamic estimation of the VAR model and SIs. To estimate the rolling SIs, the appropriate window length and forecast horizon h have to be chosen. These lengths depend on the issue of interest and data availability. Some research observes business cycles and uses greater values for h and rolling window length, whilst others observe shorter horizons due to observing financial markets, etc. (some examples for h include: 12 quarters in [85,86], 12 months in [87], 12 and 24 months in [88]; while the length of the rolling window differs again due to the subject matter: from 30 in [88], to a 5-year window in [89]). This research for the dynamic analysis, as in static one chooses h = 24 months for every country except 36 months for Croatia, Slovenia, Estonia, and Lithuania. Regarding the length of rolling windows, the basic length was chosen of 50 months for every country except 84 months for the four aforementioned countries which have more data available. The robustness checking of the results (next subsection) includes changing the lengths of rolling indices and more details will be given there. The rolling total SIs are shown in Figure A2a–i in Appendix A, denoted with “50” and “84” for the basic chosen lengths as previously mentioned. Other values (e.g., denoted with “48” and “54” are for robustness checking and will be, as mentioned, commented in the next subsection). Figure A2 compares the dynamics of EPU and the total SI for every country. If the total SI is highly dependent on the EPU, the co-movements will be very similar and this is true for those countries whose risk and return series are sensitive to EPU shocks. Some of the major findings here include: Bulgarian EPU and the total SI are not much correlated, which is in line with previous comments on this country, as well as the results in [90,91], who found that the Bulgarian economy was the least synchronized with the rest of the European Union. The Brexit uncertainty has affected the Czech Republic, Estonia, and Poland in the greatest manner. Other countries did not exhibit SI increase due to Brexit vote in 2016, which is in line with findings in [83]. Several countries experienced an increase of SI at end of 2018/beginning of 2019, due to the flattening of the yield curves of major economies in the world (USA, Germany), which is some of the first indicators of a future recession.

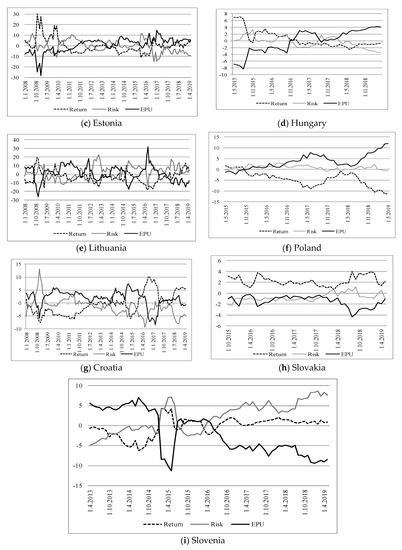

Figure A3a–i in Appendix A depicts rolling net SIs for every country so that variables can be described as net emitter or net receivers of shocks in the model. This figure only indicates the net value of each SI for a variable in the VAR model, whereas Figure A4a–i will observe pair wise spillover indices so that detailed insights can be obtained for every pair of variables in the model. Firstly, Figure A3 indicates the following. Return series was the net receiver of shocks for Bulgaria, whilst the EPU was the net emitter over the entire period. The values of all three indices are rather small, which is in line with the static results and [39,92], where it is explained that the overall uncertainty has gone down in Bulgaria after 2013 due to the industry sector. The Czech Republic is characterized with the return series as a net emitter of shocks, except Brexit shocks in 2016 (risk was the net emitter). EPU was the net emitter of shocks in Estonia only in the last part of the observed period, beforehand the return and risk series were interchanging their positions as net emitters of shocks. This is in line with results in [39]. Hungary is experiencing an increase of EPU spillovers over the entire observed period, and especially in the last part (end of 2018/beginning of 2019 due to global uncertainty rise). EPU was net emitter for Lithuania only in time of Brexit shocks in 2016, but the sovereign debt crisis which started in 2012 was characterized by the risk variable to be the net emitter of shocks. Poland and Croatia exhibited return as net receivers of shocks the majority of the time, with EPU being net emitter in the most percentage of the whole period. Slovakia had Return series as the net emitter, with EPU being the net receiver in the whole observed period. Finally, Slovenian EPU spillovers have been declining over the entire period, whilst Risk ones were increasing. Such results could be very insightful for (potential) international and domestic investors. Namely, changing economic and policy uncertainty, as seen in Figure A3 affects all of the risks and returns differently. If a country’s risk and/or return series are the net receiver of shocks, this indicates that shocks from EPU are spilled over on a particular stock market and negative shocks could have side effects on portfolio risk and/or return. Moreover, if a country has EPU variable as a net receiver, this indicates that stock market shocks in risk and/or return series has such great effects that they are spilled over to the total uncertainty in Europe. This is the case of the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

Even more detailed results on the net transmission of shocks are shown in Figure A4a–i in Appendix A, where pairwise spillovers are depicted. These are interpreted as follows: e.g., by looking at spillover “return-risk”, the positive value of this index indicates that the return series has received more shocks from risk than it has given shocks to the risk. These spillovers make sense to analyze, as previous research finds out that the relationship between EPU and stock market risk and return series is not just one-directional ([18,39,40,93]). Firstly, by looking at the “return–risk” index, there are almost no spillovers between the two series for Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Slovenia, i.e., the values are very close to zero. The return series spills over more to risk for cases of Estonia (in 2016 Brexit case) and Croatia (in the financial crisis of 2008–2009). The risk to return spillovers is more prominent for Lithuania and Croatia at the end of the observed period. Such findings could be important for investors and asset pricing models.

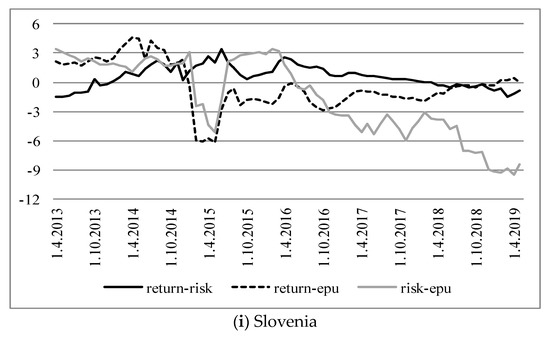

Shocks in the return series have spilled over to EPU for the Czech Republic; and Slovakia and Estonia at the beginning of the observed period, and end of the period for Slovenia. The return was the net receiver of shocks from EPU series for Poland in the entire period, with rising values of the spillover. Other spillover values were close to zero for other countries. Spillover from Risk to EPU series is prominent for Estonia and Hungary at the beginning of the period, with a reversal of the spillover direction between the two variables and countries in the second part of the period. The opposite is true for Lithuania. Finally, the Slovenian Risk series was a net emitter of shocks to the EPU variable at the end of the observed period. All these findings are important for policymakers and investors. Policymakers can obtain detailed information if shocks of return or risk series of a country could affect the total uncertainty in Europe. This evidence is found for the Czech, Slovakian, Estonian, and somewhat Slovenian markets regarding return series; and for the risk series partially for Estonian, Hungarian, Lithuanian and Slovenian markets. Thus, it could be said that these markets could diminish diversification possibilities for an international portfolio. On the other hand, policymakers need to follow closely those markets whose shocks could affect perceptions of future uncertainty, so that announcements and policy moves regarding stock market shocks could be tailored concerning those findings. However, the small values of spillover indices from EPU to the other two variables are in line with results in [46], in which little evidence of causality from EPU to stock prices was found.

4.4. Robustness Checking

Finally, the robustness of results has been checked by several approaches. First, the total rolling spillover indices have been re-estimated by changing the length of rolling windows, as advised in [36,61,67]. The basic idea is that the dynamics of the total SI should not change much by lengthening or shortening the rolling window. This was done and shown in Figure A2. In the previous subsection, comments were only made on the “50” and “84” month rolling windows. However, to save space, the SIs calculated based on other lengths (e.g., “78” and “90”) have been re-estimated for every country. If the SIs follow a similar pattern over time, it could be said that the results are robust. This is true for the majority of countries in the majority of the observed period for each one. Of course, the shorter-length rolling window based SIs capture more variability in data. There are somewhat greater differences between SIs, e.g., for Slovenia in the middle of the observed period. The reasoning could be that some other factor has affected this countries spillover between the observed variables.

Next, the rolling window correlations between all three series have been estimated and plotted in Figure A5a–i in the Appendix A. For the majority of countries, the changes of SIs preceded changes in correlations, meaning that spillovers will result with changes in correlations between the observed variables. Correlation between the risk and EPU series follows the dynamics of EPU for the majority of the observed countries, with exceptions of Croatia and Bulgaria, for which the correlation between the return and EPU series follows more closely changes in EPU. These results confirm the net spillover indices in Figure A3, in which the greatest (absolute) values of each variable in the system are stronger for the return series for the two aforementioned countries.

Finally, since much previous work focuses on the effects of EPU on risk and returns series, the rolling Granger test values have been performed within the individual country VAR model. The results are shown in Figure A6, where the p-value of the test for the null hypothesis that EPU does not Granger cause risk and return series for the observed country are compared to the critical value of 10%. These results are used to check the robustness of the values of the net spillover index for EPU in Figure A6. Findings based on Figure A6 confirm conclusions of Figure A6: when the EPU variable is the net emitter of shocks in the model, the p-value of the Granger test is lower than the critical value for Bulgaria, Czech Republic (end of period), Estonia (2014–2015 and 2017–2018 period), Hungary and Poland (both have an increase of SIs for EPU over the entire period, with the decline of respective p-values), Lithuania (Brexit 2016 period), Croatia (2014–2015 period), Slovakia (EPU is constantly the net receiver, what the p-values confirm) and Slovenia (first half of period EPU is an emitter of shocks with p-values lower than 10% and vice versa in the second half). Thus, all of these procedures confirm previous conclusions.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Previous section findings indicate that the greatest spillovers between risk, return and EPU series are found for the Czech Republic, Lithuania, Slovenia, and Poland overall. These countries’ stock markets are connected to the political and economic uncertainty the most [79,80]. This means that stock markets in the mentioned countries react much more to changes in EPU compared to the rest of the observed sample. Thus, policymakers in those countries should pay special attention when making specific moves, since the stock markets will have greater reactions. Since the CEE countries are less developed compared to other markets, the policies aimed at CEE markets should take into consideration that EPU shocks affect these markets in a significant manner. Moreover, potential investors can expect stock market reactions from different EPU shocks on those markets, making their portfolios more vulnerable.

Next, the Bulgarian stock market is the least correlated with EPU overall (which is in line with [90,91]). This could potentially have positive diversification effects on international portfolios. Furthermore, policymakers could benefit from those insights, as to tailor their decisions with the knowledge that the political and economic shocks do not affect the Bulgarian market that much. Often (here and in previous literature) mentioned Brexit uncertainty of 2016 has affected the Czech, Estonian, and Poland markets greatest, with total SIs increasing for the three countries in the peak of the UK voting date and afterward (results are in line with [83]). This indicates that the mentioned markets are more related to other developed markets and economies. Thus, investors should pay attention to economic and political shocks in the more developed countries more when having Czech, Estonian and Polish stocks in their portfolios. Other countries have somewhat individual results, with time-varying values of net spillovers of individual variables, as well as pairwise spillover indices. This means that investors should pay attention to all of the changes over time, and not use static estimation results, as the dynamics on these markets change often, which could affect the portfolio characteristics in terms of risk and/or return. If the anticipated spillovers are expected to be high, then for every individual country investor has to examine the magnitude and signs of the spillovers in order to rebalance his portfolio accordingly.

Reasoning on why the results are not identical for all countries lie upon facts that each country has its macroeconomic fundamentals and financial exposure, business cycle connectedness and synchronization ([91]), with different tax and other relevant legislation, differences in account deficits (especially ECB (European Central Bank) liquidity and financial assistance during the sovereign debt crisis, see [94] for comments on Baltic states), etc. All these for surely affect reactions of individual country risk and return series to European shocks. The model developed in [17,38] which is commonly used to explain the results of such analysis, describes the role of EPU in changing states of the economy.

The shortfalls of the study are as follows: The analyzed period for the majority of countries is rather short. This is observed as a shortfall in this study. Although some insights are given here, the results should be, of course, taken with some caution. Future work should extend the time sample if more data becomes available (not only new, but older ones become publicly available).

Future work should extend the analysis done in this research by looking at possibilities of asymmetric effects of EPU shocks on risk and return. Investor preference theory has a special part focused on asymmetric evaluation lower and upper tails of return distributions, as well as some financial models (e.g., GARCH family type models) differentiate between positive and negative news (innovation shocks). Another approach of observing asymmetries could be a quantile regression model, which is also gaining popularity in the literature due to capturing interesting results in extreme market conditions. Since the results of this paper found some significant results which were previously mentioned, there is more work to be done regarding the asymmetric models in the future. In that way, timely decisions in future policy conducting and portfolio selection (investing) could be obtained for better development of CEE markets and obtaining better portfolio results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.Š. and Z.O.; Data curation, T.Š. and Z.O.; Formal analysis, T.Š. and Z.O.; Funding acquisition, T.Š. and Z.O.; Investigation, T.Š. and Z.O.; Methodology, T.Š. and Z.O.; Project administration, T.Š. and Z.O.; Resources, T.Š. and Z.O.; Software, T.Š. and Z.O.; Supervision, T.Š. and Z.O.; Validation, T.Š. and Z.O.; Visualization, T.Š. and Z.O.; Writing—original draft, T.Š. and Z.O.; Writing—review & editing, T.Š. and Z.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the anonymous referees and their comments which have contributed to the quality of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Time span used for every country.

Table A1.

Time span used for every country.

| Country | Start Date | End Date |

|---|---|---|

| Bulgaria | August 2011 | May 2019 |

| Czech | January 2012 | May 2019 |

| Estonia | January 2001 | May 2019 |

| Hungary | March 2011 | April 2019 |

| Lithuania | January 2001 | May 2019 |

| Poland | March 2011 | May 2019 |

| Croatia | January 2001 | May 2019 |

| Slovakia | August 2011 | May 2019 |

| Slovenia | April 2006 | May 2019 |

Table A2.

Unit root test on differenced values of non-stationary variables in Table 1.

Table A2.

Unit root test on differenced values of non-stationary variables in Table 1.

| Variable | Test Value | Variable | Test Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| dCPI Lithuania | −8.286 *** | dCPI Hungary | −5.917 *** |

| dIrate Lithuania | −8.867 *** | dIrate Hungary | −6.187 *** |

| dUnemp Lithuania | −4.975 *** | dUnemp Hungary | −5.071 *** |

| dCPI Slovakia | −4.806 *** | dCPI Estonia | −7.705 *** |

| dUnemp Slovakia | −3.874 *** | dIIP Estonia | −10.896 *** |

| dCPI Croatia | −7.737 *** | dIrate Estonia | −8.038 *** |

| dIrate Croatia | −9.729 *** | dUnemp Estonia | −7.330 *** |

| dUnemp Croatia | −4.815 *** | dEPU Czech | −3.454 ** |

| dCPI Slovenia | −9.702 *** | dIIP Czech | −6.127 *** |

| dIIP Slovenia | −10.682 *** | dIIP Czech | −8.989 *** |

| dIrate Slovenia | −5.272 *** | dIrate Czech | −6.259 *** |

| dUnemp Slovenia | −6.177 *** | dUnemp Czech | −5.274 *** |

| dCPI Poland | −5.312 *** | dCPI Bulgaria | −6.578 *** |

| dIrate Poland | −3.825 *** | dIrate Bulgaria | −10.999 *** |

| dUnemp Poland | −5.356 *** | dREER Bulgaria | −7.387 *** |

| dUnemp Bulgaria | −4.188 *** |

Note: critical values of rejecting the null hypothesis are −3.46, −2.88 and −2.57 for 1%, 5% and 10% respectively. No deterministic regressors were included in the ADF equation. ** and *** denote statistical significance on 5% and 1% respectively.

Table A3.

Descriptive statistics for stationary variables for every country.

Table A3.

Descriptive statistics for stationary variables for every country.

| Return | Estonia | Lithuania | Bulgaria | Czech | Hungary | Poland | Croatia | Slovakia | Slovenia |

| Min | −0.0156 | −0.0153 | −0.0048 | −0.0047 | −0.0072 | −0.0005 | −0.0155 | −0.0041 | −0.0084 |

| Median | 0.0004 | 0.0003 | −0.0002 | 0.0004 | 0.0002 | −0.0031 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.0004 |

| Max | 0.0185 | 0.0172 | 0.0006 | 0.0040 | 0.0069 | 0.0004 | 0.0148 | 0.0063 | 0.0079 |

| SD | 0.0033 | 0.0032 | 0.0019 | 0.0018 | 0.0025 | 0.0020 | 0.0031 | 0.0017 | 0.0026 |

| Risk | Estonia | Lithuania | Bulgaria | Czech | Hungary | Poland | Croatia | Slovakia | Slovenia |

| Min | 0.0014 | 0.0020 | 0.0026 | 0.0038 | 0.0050 | 0.0035 | 0.0024 | 0.0029 | 0.0034 |

| Median | 0.0070 | 0.0060 | 0.0065 | 0.0080 | 0.1003 | 0.0082 | 0.0072 | 0.0098 | 0.0075 |

| Max | 0.0324 | 0.0505 | 0.0199 | 0.0182 | 0.0257 | 0.0275 | 0.0579 | 0.0234 | 0.0414 |

| SD | 0.0053 | 0.0055 | 0.0029 | 0.0030 | 0.0042 | 0.0037 | 0.0067 | 0.0038 | 0.0052 |

| CPI | Estonia | Lithuania | Bulgaria | Czech | Hungary | Poland | Croatia | Slovakia | Slovenia |

| Min | −0.0124 | −0.0149 | −0.0122 | −0.0123 | −0.0023 | −0.0090 | −0.0284 | −0.0086 | −0.0187 |

| Median | −0.0002 | 0.0003 | 0.0033 | 0.0000 | 0.0022 | 0.0000 | −0.0003 | −0.0004 | −0.0146 |

| Max | 0.0115 | 0.0180 | 0.0087 | 0.0081 | 0.0151 | 0.0070 | 0.0220 | 0.0060 | 0.0166 |

| SD | 0.0049 | 0.0056 | 0.00044 | 0.0033 | 0.0047 | 0.0031 | 0.0059 | 0.0027 | 0.0051 |

| IIP | Estonia | Lithuania | Bulgaria | Czech | Hungary | Poland | Croatia | Slovakia | Slovenia |

| Min | −0.1177 | −0.2708 | −0.0545 | −0.0838 | −0.0471 | −0.0712 | −0.1360 | −0.0539 | −0.1284 |

| Median | −0.0023 | 0.0581 | 0.0384 | −0.0002 | 0.0408 | 0.0534 | 0.0219 | 0.0486 | 0.0011 |

| Max | 0.1023 | 0.3476 | 0.1293 | 0.0644 | 0.1186 | 0.1459 | 0.1474 | 0.1412 | 0.1464 |

| SD | 0.0059 | 0.0925 | 0.0334 | 0.0256 | 0.0350 | 0.0319 | 0.0546 | 0.0356 | 0.0397 |

| Irate | Estonia | Lithuania | Bulgaria | Czech | Hungary | Poland | Croatia | Slovakia | Slovenia |

| Min | −1.2600 | −1.4830 | −1.4500 | −0.1900 | −0.8900 | −0.4300 | 0.470 | −0.6730 | −0.9457 |

| Median | −0.0037 | −0.0047 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | −0.0300 | 0.0000 | 2.710 | −0.0021 | −0.0024 |

| Max | 1.8700 | 1.3459 | 1.2200 | 0.2500 | 0.6700 | 0.2100 | 11.260 | 2.7420 | 0.3274 |

| SD | 0.0365 | 0.3370 | 0.2929 | 0.0712 | 0.2461 | 0.1020 | 2.7360 | 0.6505 | 0.1535 |

| REER | Estonia | Lithuania | Bulgaria | Czech | Hungary | Poland | Croatia | Slovakia | Slovenia |

| Min | −0.0513 | −0.0689 | −0.0191 | −0.0341 | −0.0972 | −0.1044 | −0.0595 | −0.0430 | −0.0460 |

| Median | 0.0198 | 0.0119 | −0.0006 | 0.0005 | −0.0097 | −0.0091 | 0.0085 | 0.0065 | 0.0030 |

| Max | 0.0852 | 0.1118 | 0.0285 | 0.0473 | 0.1039 | 0.0799 | 0.0666 | 0.0403 | 0.0434 |

| SD | 0.2203 | 0.0354 | 0.0097 | 0.0152 | 0.0380 | 0.0386 | 0.0232 | 0.0157 | 0.0181 |

| Unemp | Estonia | Lithuania | Bulgaria | Czech | Hungary | Poland | Croatia | Slovakia | Slovenia |

| Min | −1.2000 | −1.0000 | −0.5000 | −0.4000 | −0.6000 | −0.5000 | −0.5000 | −0.3000 | −0.4000 |

| Median | −0.1000 | −0.1000 | −0.1000 | −0.1000 | −0.1000 | −0.1000 | −0.1000 | −0.1000 | 0.0000 |

| Max | 1.8000 | 1.0000 | 0.3000 | 0.2000 | 0.3000 | 0.8000 | 0.4000 | 0.2000 | 0.6000 |

| SD | 0.0265 | 0.3227 | 0.1644 | 0.1083 | 0.1572 | 0.2805 | 0.1764 | 0.1034 | 0.1929 |

| EPU | Estonia | Lithuania | Bulgaria | Czech | Hungary | Poland | Croatia | Slovakia | Slovenia |

| Min | 3.865 | 3.865 | 4.717 | 3.865 | 4.717 | 4.717 | 3.865 | 4.717 | 3.865 |

| Median | 5.004 | 5.004 | 5.322 | 5.116 | 5.288 | 5.288 | 5.004 | 5.322 | 5.116 |

| Max | 6.071 | 6.071 | 6.071 | 6.071 | 6.071 | 6.071 | 6.071 | 6.071 | 6.071 |

| SD | 0.4342 | 0.4342 | 0.262 | 0.4141 | 0.261 | 0.261 | 0.4342 | 0.262 | 0.4141 |

Note: min, max and SD denote minimal, maximal values and standard deviation respectively.

Figure A1.

Impulse response functions (bootstrapped values have been estimated based on 1000 replications) for every country.

Figure A2.

Rolling total spillover indices (left axis) for every country compared to EPU (right axis).

Figure A3.

Rolling net spillover indices for every country.

Figure A4.

Rolling pair wise spillover indices for every country.

Figure A5.

Rolling correlations between return-EPU series and risk-EPU series (left axis) compared to rolling total spillover indices (right axis).

Figure A6.

Rolling Granger test p-value for EPU shocks as cause.

References

- Fama, E.F.; French, K.R. The cross-section of expected stock returns. J. Financ. 1992, 47, 427–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; French, K.R. Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. J. Financ. Econ. 1993, 33, 3–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; French, K.R. Size and book-to-market factors in earnings and returns. J. Financ. 1995, 50, 131–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart, M.M. On persistence in mutual fund performance. J. Financ. 1997, 52, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pástor, L.; Stambaugh, R.F. Liquidity risk and expected stock returns. J. Political Econ. 2003, 111, 642–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.F.; Roll, R.; Ross, S.A. Economic forces and the stock market. J. Bus. 1986, 59, 383–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregoriou, A.; Kontonikas, A.; MacDonald, R.; Montagnoli, A. Monetary policy shocks and stock returns: Evidence from the British market. Financ. Mark. Portf. Manag. 2009, 23, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, M.J.; Protopapadakis, A.A. Macroeconomic factors do influence aggregate stock returns. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2002, 15, 751–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.R.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J. Measuring economic policy uncertainty. Q. J. Econ. 2016, 131, 1593–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J. Measuring Economic Policy Uncertainty, Manuscript; University of Chicago, Booth School of Business: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann, R.; Elstner, S.; Sims, E.R. Uncertainty and economic activity: Evidence from business survey data. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 2013, 5, 217–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnizova, L.; Li, J.C. Economic policy uncertainty, financial markets and probability of US recessions. Econ. Lett. 2014, 125, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Ratti, R.A. Structural oil price shocks and policy uncertainty. Econ. Model. 2013, 35, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, C.R.; Huang, Y.S. Economic policy uncertainty and corporate investment: Evidence from China. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2014, 26, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.; Ilut, C.L.; Schneider, M. Uncertainty shocks, asset supply and pricing over the business cycle. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2017, 85, 810–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, T.G.; Brown, S.J.; Tang, Y. Is economic uncertainty priced in the cross-section of stock returns? J. Financ. Econ. 2017, 126, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pástor, L.; Veronesi, P. Political uncertainty and risk premia. J. Financ. Econ. 2013, 110, 520–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakakis, N.; Chatziantoniou, I.; Filis, G. Dynamic co-movements of stock market returns, implied volatility and policy uncertainty. Econ. Lett. 2013, 120, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, S.; Ghosh, P.; Rangan, S.P. Economic Policy Uncertainty and Economic Growth in India; IIM: Bengalore, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R.C. An intertemporal capital asset pricing model. Econometrica 1973, 41, 867–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernanke, B.S. Irreversibility, uncertainty, and cyclical investment. Q. J. Econ. 1983, 98, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.; Siegel, D. The value of waiting to invest. Q. J. Econ. 1986, 101, 707–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindyck, R.S. Irreversible Investment, Capacity Choice, and the Value of the Firm. Am. Econ. Rev. 1988, 78, 969–985. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, A. Entry and exit decisions under uncertainty. J. Political Econ. 1989, 97, 620–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Open Market Committee. Minutes of the December 2009 Meeting. 2009. Available online: http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcminutes20091216.htm (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook: Coping with High Debt and Sluggish Growth; IMF Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook: Hopes, Realities, Risks; IMF Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- ECB. Financial Stability Review. 2017. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/financialstabilityreview201705.en.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- VOX EU. Global Uncertainty Is Rising, and that Is a Bad Omen for Growth. 2018. Available online: https://voxeu.org/article/global-uncertainty-rising-and-bad-omen-growth (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- Deutsche Bank. Economic Policy Uncertainty in Europe. 2018. Available online: https://www.dbresearch.com/PROD/RPS_EN-PROD/PROD0000000000460235/Economic_policy_uncertainty_in_Europe%3A_Detrimental.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- OECD. A Fragile Global Economy Needs Urgent Cooperative Action. 2019. Available online: https://oecdecoscope.blog/2019/05/21/a-fragile-global-economy-needs-urgent-cooperative-action/ (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- OECD. OECD Economic Outlook; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019; Volume 2019, Issue 1: Preliminary version. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2019. Available online: https://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-19-3850_en.htm (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- Škrinjarić, T. Stock market stability on selected CEE and SEE markets: A quantile regression approach. Post-Communist Econ. 2019, 32, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köke, J.; Schröder, M. The prospects of capital markets in Central and Eastern Europe. East. Eur. Econ. 2003, 41, 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, F.X.; Yilmaz, K. Measuring financial asset return and volatility spillovers, with application to global equity markets. Econ. J. 2009, 119, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, F.X.; Yilmaz, K. Better to give than to receive: Predictive directional measurement of volatility spillovers. Int. J. Forecast. 2012, 28, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pástor, L.; Veronesi, P. Uncertainty about government policy and stock prices. J. Financ. 2012, 67, 1219–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sum, V. Economic policy uncertainty and stock market performance: Evidence from the European Union, Croatia, Norway, Russia, Switzerland, Turkey and Ukraine. J. Money Invest. Banking 2019, 25, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sum, V. Economic Policy Uncertainty and Stock Market Returns. International Reviewof Applied Financial Issues and Economics, Forthcoming. 2012. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2073184 (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- Ko, J.H.; Lee, C.M. International economic policy uncertainty and stock prices: Wavelet approach. Econ. Lett. 2015, 134, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, T. Economic policy uncertainty and stock market volatility. Financ. Res. Lett. 2015, 15, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.L.; Balcilar, M.; Gupta, R.; Chang, T. The causal relationship between economic policy uncertainty and stock returns in China and India: Evidence from a bootstrap rolling window approach. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2016, 52, 674–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, B.; Sekhposyan, T. Macroeconomic uncertainty indices for the euro area and its individual member countries. Empir. Econ. 2017, 53, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arouri, M.; Estay, C.; Rault, C.; Roubaud, D. Economic policy uncertainty and stock markets: Long-run evidence from the US. Financ. Res. Lett. 2016, 18, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-P.; Liu, S.-B.; Hsueh, S.-J. The Causal Relationship between Economic Policy Uncertainty and Stock Market: A Panel Data Analysis. Int. Econ. J. 2016, 30, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, C.; Cunado, J.; Gupta, R.; Hassapis, C. Economic policy uncertainty and stock market returns in PacificRim countries: Evidence based on a Bayesian panel VAR model. J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 2017, 40, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirgaip, B. The Causal Relationship between Stock Markets and Policy Uncertainty in OECD Countries. RSEP International Conferences on Social Issues and Economic Studies. 2017. Available online: https://rsepconferences.com/my_documents/my_files/3_BURAK.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- Asgharian, H.; Christiansen, C.; Hou, A.J. Economic Policy Uncertainty and Long-Run Stock Market Volatility and Correlation; Available at SSRN 3146924; Department of Economics and Business Economics, Aarhus University: Aarhus, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Debata, B.; Mahakud, J. Economic policy uncertainty and stock market liquidity: Does financial crisis make any difference? J. Financ. Econ. Policy 2018, 10, 112–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhu, S.; O’Sullivan, N.; Sherman, M. The role of economic uncertainty in UK stock returns. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2019, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramey, G.; Ramey, V.A. Cross-Country Evidence on the Link between Volatility and Growth (No. w4959); National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Leahy, J.V.; Whited, T.M. The Effect of Uncertainty on Investment: Some Stylized Facts (No. w4986); National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Novy, D.; Taylor, A.M. Trade and Uncertainty (No. w19941); National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gauvin, L.; McLoughlin, C.; Reinhardt, D. Policy Uncertainty Spillovers to Emerging Markets–Evidence from Capital Flows; Bank of England (No. 512.): London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Biljanovska, N.; Grigoli, F.; Hengge, M. Fear thy Neighbor: Spillovers from Economic Policy Uncertainty; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Metghalchi, M.; Hajilee, M.; Hayes, L.A. Return Predictability and Market Efficiency: Evidence from the Bulgarian Stock Market. East. Eur. Econ. 2018, 57, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghel, D.G. Intraday Market Efficiency for a Typical Central and Eastern European Stock Market: The Case of Romania. Rom. J. Econ. Forecast. 2017, 20, 88–109. [Google Scholar]

- Shynkevich, A. Return predictability in emerging equity market sectors. Appl. Econ. 2017, 49, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metghalchi, M.; Hayes, L.A.; Niroomand, F. A technical approach to equity investing in emerging markets. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2019, 37, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, F.X.; Yilmaz, K. Equity market spillovers in the Americas. Financ. Stab. Monet. Policy Cent Bank. 2011, 15, 199–214. [Google Scholar]

- Lütkepohl, H. Introduction to Multiple Time Series Analysis; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lütkepohl, H. New Introduction to Multiple Time Series Analysis; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lütkepohl, H. Vector Autoregressive Models; Economics Working Paper ECO 2011/30; European University Institute: Florence, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Demirer, M.; Gokcen, U.; Yilmaz, K. Financial Sector Volatility Connectedness and Equity Returns; Banque de France: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Urbina, J. Financial Spillovers across Countries: Measuring Shock Transmissions; Munich Personal RePEc: Archive, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Koop, G.; Pesaran, M.H.; Potter, S.M. Impulse response analysis in nonlinear multivariate models. J. Econom. 1996, 74, 119–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, H.H.; Shin, Y. Generalized impulse response analysis in linear multivariate models. Econ. Lett. 1998, 58, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economic Policy Uncertainty. 2019. Available online: https://www.policyuncertainty.com/ (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- Ozturk, E.O.; Sheng, X.S. Measuring global and country-specific uncertainty. J. Int. Money Financ. 2018, 88, 276–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- Investing. 2019. Available online: https://www.investing.com (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- Pástor, L.; Veronesi, P. Explaining the puzzle of high policy uncertainty and low market volatility. VOX Column 2017, 25. Available online: https://voxeu.org/article/puzzle-high-policy-uncertainty-and-low-market-volatility (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- Brogaard, J.; Detzel, A. The asset-pricing implications of government economic policy uncertainty. Manag. Sci. 2015, 61, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiralay, S.; Bayraci, S. Central and Eastern European Stock Exchanges under Stress: A Range-Based Volatility Spillover Framework. Financ. A Uver Czech J. Econ. Financ. 2015, 65, 411–430. [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua, M. Asymmetric Volatility Spillovers between Developed and Developing European Countries (No. 2018/2); Magyar Nemzeti Bank (Central Bank of Hungary): Budapest, Hungary, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stoica, O.; Diaconașu, D.E. Analysis of interdependencies between Austrian and CEE stock markets. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Finance and Banking, Ostrava, Czech Republic, 12–13 October 2011; Silesian University, School of Business Administration: Karviná, Czech Republic, 2011; pp. 616–627. [Google Scholar]

- Naumovski, A. Linkages and relationships between South East European and developed stock markets before and after the global Financial crisis and the European debt crisis. In Proceedings of 1st International Conference on Financial Analysis; Dedi, L., Orsag, S., Eds.; Croatian Association of Financial Analysts; University of Zagreb, Faculty of Economics & Business: Zagreb, Croatia, 2016; pp. 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Baele, L.; Bekaert, G.; Schäfer, L. An Anatomy of Central and Eastern European Equity Markets; Columbia Business School: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 15–71. [Google Scholar]

- Égert, B.; Kočenda, E. Interdependence between Eastern and Western European stock markets: Evidence from intraday data. Econ. Syst. 2007, 31, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietovus Bankas. The Lithuanian Economic Review; Lietuvos Bankas: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Das, D.; Kannadhasan, M.; Bhattacharyya, M. Do the emerging stock markets react to international economic policy uncertainty, geopolitical risk and financial stress alike? N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2019, 48, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škrinjarić, T. Stock market reactions to Brexit: Case of selected CEE and SEE stock markets. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2019, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, I.C. The source of global stock market risk: A viewpoint of economic policy uncertainty. Econ. Model. 2017, 60, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakakis, N.; André, C.; Gupta, R. Dynamic spillovers in the United States: Stock market, housing, uncertainty, and the macroeconomy. South. Econ. J. 2016, 83, 609–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakakis, N.; Breitenlechner, M.; Scharler, J. Business cycle and financial cycle spillovers in the G7 countries. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2015, 58, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škrinjarić, T. Examining the Causal Relationship between Tourism and Economic Growth: Spillover Index Approach for Selected CEE and SEE Countries. Economies 2019, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škrinjarić, T.; Čižmešija, M. Investor attention and risk predictability: A spillover index approach. In Proceedings of the 15th International Symposium on Operations Research in Slovenia, Bled, Slovenia, 25–27 September 2019; pp. 423–428. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, K. Business Cycle Spillovers. In Koc University-TUSIAD Economic Research Forum Working Papers; Koç University-TUSIAD Economic Research Forum: Istanbul, Turkey, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Filis, G.; Floros, C.; Leon, C.; Beneki, C. Are EU and Bulgarian business cycles synchronized. J. MoneyInvest. Bank. 2010, 14, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kovačić, Z.; Vilotić, M. Assessing European Business Cycles Synchronization (No. 79990); Munich Personal RePEc Archive: Munich, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, E. Constructing an Uncertainty Indicator for Bulgaria; Discussion Papers DP/109/2018; Bulgarian National Bank: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Antonakakis, N.; Chatziantoniou, I.; Filis, G. Dynamic Co-Movements between Stock Market Returns and Policy Uncertainty; MPRA: Munich, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Darvas, Z. Intra-Euro Rebalancing Is Inevitable but Insufficient (No. 2012/15). Bruegel Policy Contribution. 2012. Available online: https://www.bruegel.org/2012/08/intra-euro-rebalancing-is-inevitable-but-insufficient/ (accessed on 1 September 2019).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).