Abstract

The contribution of this article is quadruple. It (1) unifies various schemes of premodels/models including situations such as presheaves/sheaves, sheaves/flabby sheaves, prespectra/-spectra, simplicial topological spaces/(complete) Segal spaces, pre-localised rings/localised rings, functors in categories/strong stacks and, to some extent, functors from a limit sketch to a model category versus the homotopical models for the limit sketch; (2) provides a general construction from the premodels to the models; (3) proposes technics that allow one to assess the nature of the universal properties associated with this construction; (4) shows that the obtained localisation admits a particular presentation, which organises the structural and relational information into bundles of data. This presentation is obtained via a process called an elimination of quotients and its aim is to facilitate the handling of the relational information appearing in the construction of higher dimensional objects such as weak -categories, weak -groupoids and higher moduli stacks.

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation 1

There is an abundant literature on how to construct an algebraic object from one of its presentations [1,2,3,4,5]—this process will be referred to as a localisation. It is also well-known that the category of algebraic objects will satisfy strict universal properties if the objects themselves can be distinguished from their presentations by strict properties and, similarly, the category will usually satisfy weak universal properties if the objects can be distinguished from their presentations by weak properties, but little is known about how to derive strict universal properties for the category when the algebraic objects are only characterised by weak properties. One of the goals of the present paper is to address this lack.

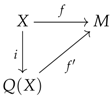

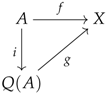

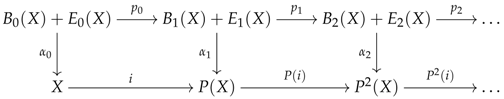

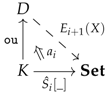

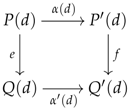

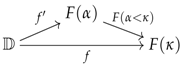

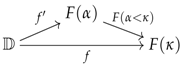

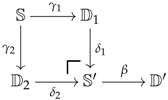

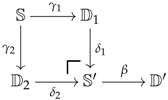

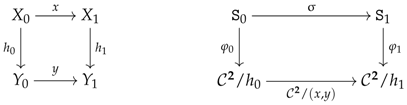

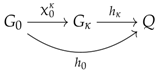

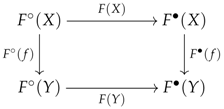

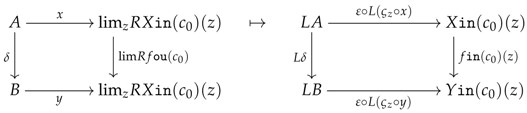

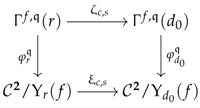

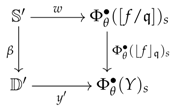

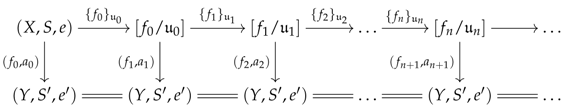

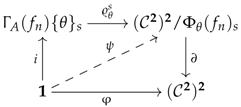

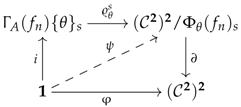

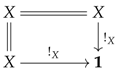

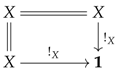

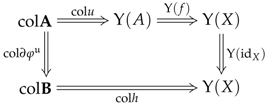

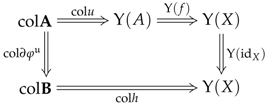

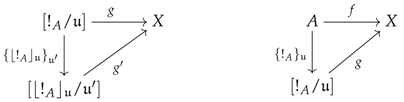

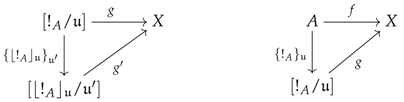

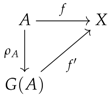

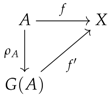

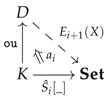

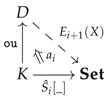

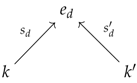

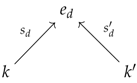

If we think of an algebraic object as a model for a limit sketch [1], then algebraic objects can usually be distinguished from their presentations by lifting properties. Specifically, in the case of a limit sketch D, the presentations are given by the functors while the models are given by those presentations that preserve the chosen limits of D; as shown in [3], this type of property can be expressed in terms of a lifting property in the functor category . On the other hand, the localisation of a presentation X into a model is endowed with a reflection property, which equips X with a map such that for every arrow where M is a model, there exists an arrow making the following diagram commute.

If the lifting properties characterising the models are strict, then one is able to show that the reflection is strict, that is to say that the arrow is unique for any given . For instance, in [3], one starts by characterising the models via strict lifting properties and the strictness of these is naturally carried over to the reflection property. This is the same idea in [4] where the author is able to construct a (strict) reflection from the strict lifting properties inherently associated with well-pointed endofunctors.

On the other hand, if the lifting properties are weak, then one is usually only able to show that the reflection is weak, in which case the arrow is only proven to exist. For instance, in [6], the small object argument (recall that this argument comes from Homotopy Theory, which mostly, if not only, deals with weak lifting properties; see [7,8]) is used to construct weak reflections for subcategories of injective objects.Similarly, in Garner’s framework [9,10], the small object argument is generalised to construct weak homomorphisms of ∞-categories à la Batanin [11] while the possibility to construct ∞-categories is assumed: the reason being that ∞-categories are objects that can be characterised by strict lifting properties [12] (Corollary 1.19) while weak homomorphisms between these do not require such a strictness.

However, to the best of my knowledge, there has not been any published work explaining how to obtain strict reflection properties from weak lifting constructions such as the small object argument. In fact, it is not even clear how to obtain strict universal properties from weak characterisations in general. For instance, in [13], essential weak factorisation systems were introduced to study injective and projective hulls, which are meant to capture canonical envelops of injective and projective objects, with the goal of strengthening the lifting properties associated with the usual associated replacements (see intro. ibid.), but it is not said if these hulls can satisfy strict universal properties; in fact [14] gives a hint that this is unlikely and states that only an almost reflection property can be shown. The paper even emphasises the need of methods to pass from a weak setting to a strict one in its last section [14] (Section 4), in which it is asked if it is possible to know when strict universal properties, such as naturality and functoriality, can be shown to be satisfied by a given weak reflection.

In an area of Mathematics in which the weakening of definitions and theories (e.g., ∞-topos theory, univalent homotopy type theory, devired algebraic geometry, etc.) have now taken more and more importance, but whose language—Category Theory—also takes advantage of strict universal properties, it is, indeed, of interest to know if there are theorems that allow one to determine whether a set of weak lifting properties defining a type of algebraic object can provide the associated category with a strict universal property—at least stricter than the expected one.

The present paper is an effort to provide a set of technics and theorems showing that such a scheme is possible. Precisely, one of the main contributions of this paper is to propose a language (or context) in which it is possible to say if a category of algebraic objects that are characterised by weak lifting properties can be shown to possess a strict universal property (see Section 1.3). We will even show that the proposed argument is a generalisation of Quillen’s small object argument (see Corollary 2) and will thus answer one of our earlier questions. The theorems given herein are meant to be generalised in future work (in which the boundary between strictness and weakness will become blurrier), the purpose being to pave the way for the construction of models taking their values in higher categorical structures.

1.2. Motivation 2

The second matter that motivates the present paper is the so-called elimination of quotients mentioned in the title, which basically comes down to conclude that the way we encode an object is as important as its inherent properties. For instance, it is this same type of ideas that motivated

- ▹

- the introduction of the elimination of imaginaries, in Shelah’s Model Theory [15,16], in which quotients are eliminated in the form of definable quotient maps by using the various sorts available from the ambient (multi-sorted) theory;

- ▹

- the development of the concept of covering space, in Algebraic Topology [17], that provides ways to blow up the quotients acting on a space and to bring out its homotopical properties by studying the automorphisms acting on the resulting quotient maps;

- ▹

- the definition of stack, in Algebraic Geometry [18], due to the existence of non-trivial automorphisms that may occur because of the different ways a moduli space can be represented.

To really understand how the coding of objects, and, even that of sets, matters from the point of view of their algebraic structures, let us consider an example. Take a set X and consider the coproduct encoded by the following logical specification:

If one takes R to be the binary relation on that identifies with for every , then the quotient is obviously isomorphic to X. However, in much the same way as it is fundamental to not confuse an isomorphism with an identity, it is, here, important to understand that is not same as X. From the point of view of the present paper, the difference between X and lies in the implicit algebraic structure with which is equipped. This object can indeed be seen as a surjection equipped with two sections whose cospan structure defines a universal cocone, and this structure is noticeable even thought is isomorphic to a mere set. In other words, the quotient can be seen as living way beyond the category of sets, for the simple reason that isomorphisms are not the same as identities.

All this shows that the way we construct algebraic objects matters quite substantially, mainly because the algebraic properties coming along with their representations can turn out to be either very useful or extremely cumbersome (e.g., X versus ).

The goal of our so-called ‘elimination of quotients’ will be to eliminate the cumbersome quotients that may occur in the representation of algebraic objects and organise, in the form of quotient maps, the useful ones. Here, I feel important to mention that such a re-organisation is possible because our objects are characterised by weak lifting properties, which allow more freedom than strict ones.

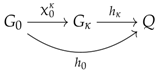

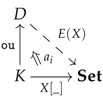

If we look at how Kelly [4] (Theorem 10.2) constructs algebraic objects, and to be more specific, models for some limit sketch , where K denotes the set of limit cones associated with D, we see that he isolates each cone and constructs, for each of these and every presentation , a well-pointed endofunctor where the object completes the presentation X with operations required by the sub-theory of . To complete X with respect to the operations required by the whole theory , he pushes out the wide span made of the arrows , for all , to obtain a well-pointed endofunctor . In particular, each cone is equipped with a factorisation as follows:

Finally, the reflector associated with the theory is computed through a transfinite composition of the following form:

Isolating each cone c in K and proceeding to a pushout of the well-pointed endofunctors is a necessity if one wants to use the very neat and compact formalism of well-pointed endofunctors. However, this pushout procedure, as elegant as it may be, adds more cumbersome quotients than useful ones. Precisely, the wide pushout of the objects looks more like the type because it mostly identifies all the copies of X living in each through the maps .

As we can imagine, these cumbersome quotients become much more abundant when enriching our algebraic objects to other categories than and it would not be imaginable to be willing to do combinatorics with representations that repeat and contract the same information over and over. Not only do the results proposed in the present article avoid these cumbersome quotients, but they also bring out the hidden algebraic structure of the useful ones, where, here, the term ‘algebraic structure’ is used in the sense previously discussed for the quotient .

In fact, our results go in the direction of Lawvere’s work [5], in which the concept of congruence is used to construct a reflector from the category of presentations to that of models by showing how the quotients act on the free algebra functor applied on the presentations [5] (Theorem 5.1). It is worth noting that the concept of congruence has given rise to a very rich theory regarding the characterisation of congruence lattices for varieties of algebras [19,20]. Our results can therefore be seen as a refined extension of Lawvere’s work. This refinement is presented in the form of a formal language that could be seen as suitable for a generalisation of Congruence Lattice Theory to more general objects than those proposed by Lawvere.

1.3. Results for Motivation 1

In the same fashion as there are categories of models for a theory [1], or categories of fibrants objects [21] or even systems of fibrant objects [22], it is, here, proposed the definition of system of premodels (see Definition 3), which gathers in the same structure a category of presentations together with maps along which the models are defined via weak lifting properties. An interesting feature of this structure is that it encompasses many examples that are meant to be captured operibus citatis; particular examples can also be found in [23,24,25,26]. There is also a novelty in the fact that the maps along which the weak lifting properties are defined are not maps in the category of values or that of presentations, but in a category whose level of definition allows one to verify whether the subcategory of the resulting models possesses a strict reflection property. For instance, this allows us to retrieve and explain the strict reflection property associated with the models for a limit sketch.

If we restrict ourselves to algebraic objects defined by limit-preserving functors, say valued in a category in which choices of colimits are obvious, a system of premodels is given by:

- (1)

- a limit sketch ;

- (2)

- a category with enough limits and pushouts, if not all;

- (3)

- a subcategory ;

- (4)

- for every cone , a set of commutative squares in , say as follows:

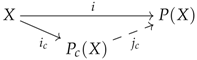

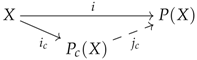

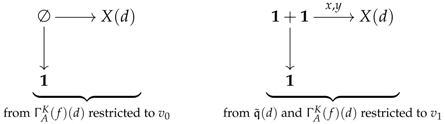

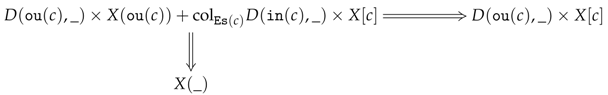

Before giving the definition of a model for this structure, we need to recall that a cone c in K is a natural transformation where is an object in D, is a small category, is the obvious constant functor picking out the object in D and is some functor . Now, a model for the previous structure is a functor in such that for every , the canonical arrow:

for which we shall prefer the more compact notation , is orthogonal in the arrow category to every commutative square in (as shown below):

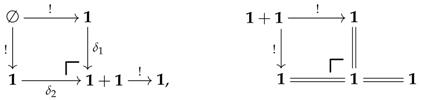

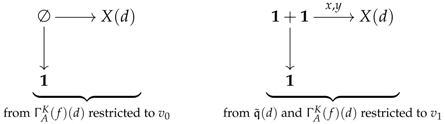

In the case of limits sketches, we retrieve the usual definition of model by taking, for every cone , the following pair of commutative squares in ; the leftmost one encodes the surjectiveness of the map while the other one encodes its injectiveness:

One of the very advantages of this language is to allow the specification of more general arrows than bijections such as weak equivalences (see characterisation in [27] (Lemma 7.5.1)). This explains why this language is expected to be generalised to higher categorical structures in the future.

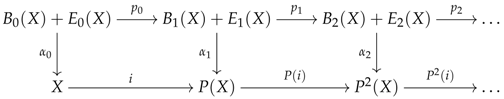

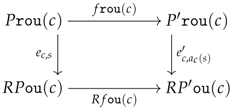

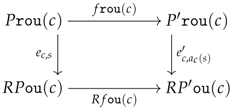

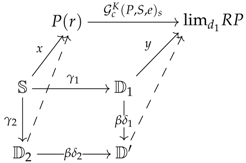

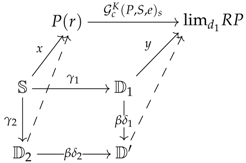

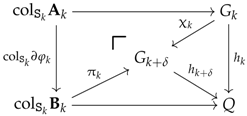

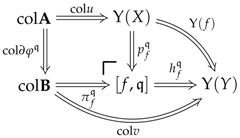

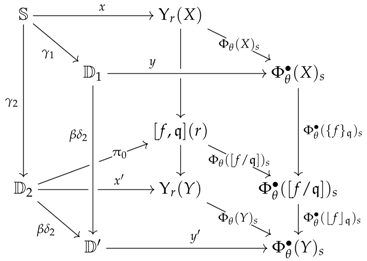

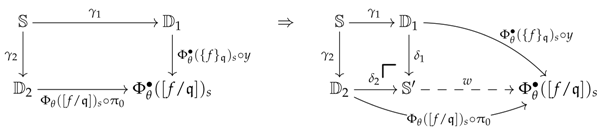

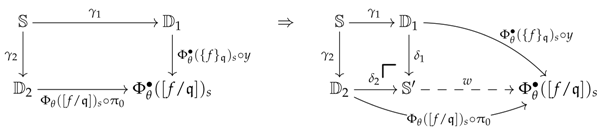

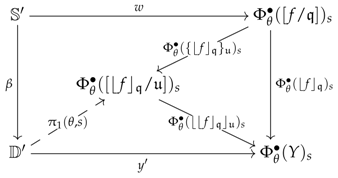

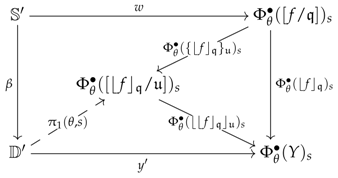

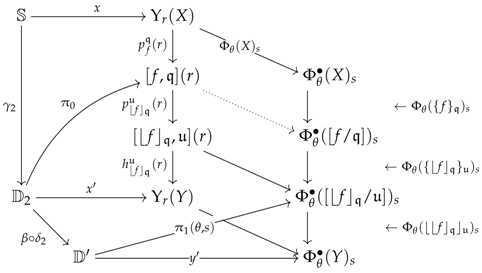

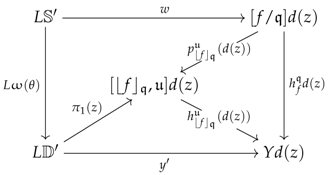

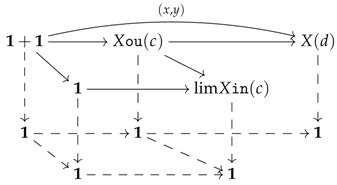

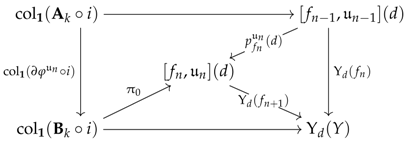

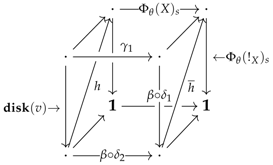

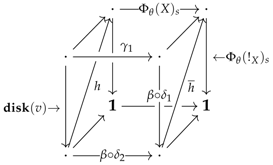

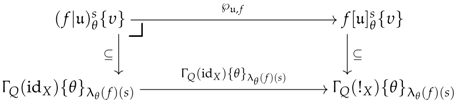

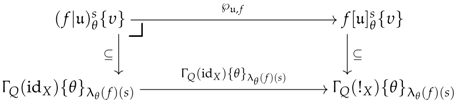

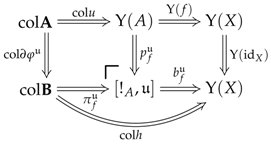

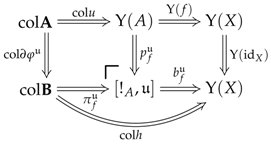

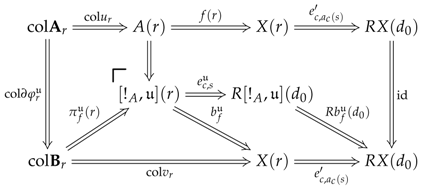

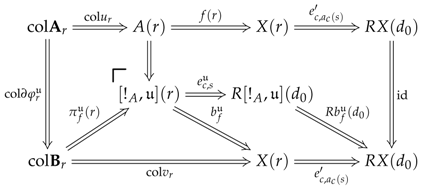

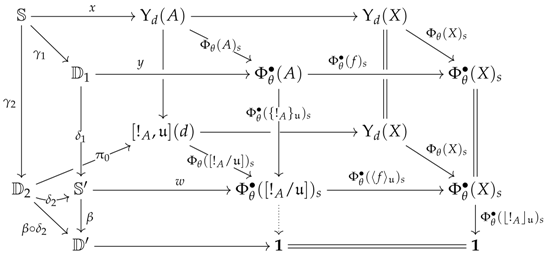

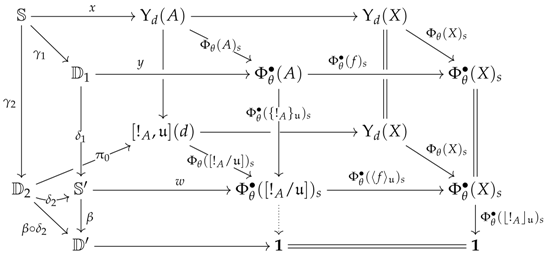

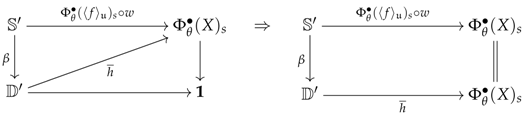

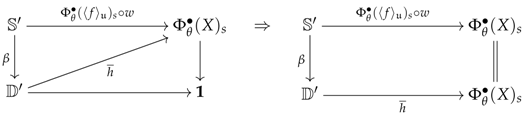

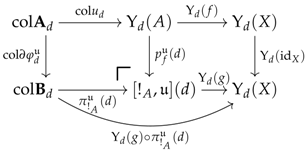

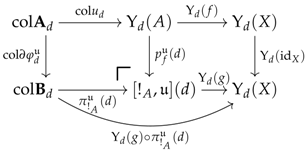

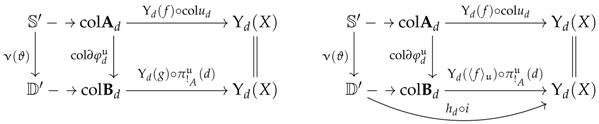

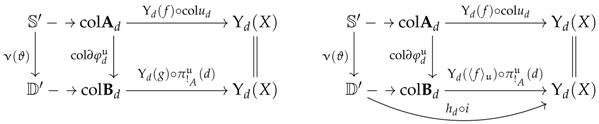

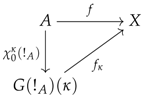

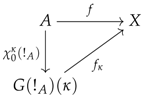

Now, our main result, given in Theorems 8 and 9, can be simplified in terms of Theorem 1, in which items (i) and (ii) are in fact redundant. The statement makes use of the arrow , which denotes, for every commutative square contained in and every , the universal arrow induced by the pair of arows and under the pushout (denoted by ) of the arrows and .

Theorem 1.

Suppose that is an identity. For every object A in , there exists an arrow in (Theorem 9) such that for every arrow in where X is a model for the system of premodels, if

- (i)

- the map β is an epimorphism for every square in and every ;

- (ii)

- the arrow is a monomorphism in ;

- (iii)

- the arrow is an epimorphism for every square in and every ,

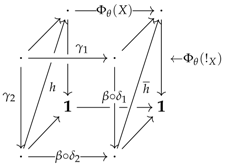

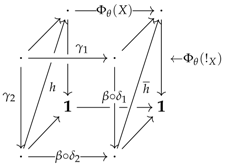

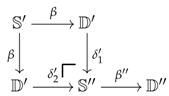

then there exists a unique arrow making the following diagram commute (Theorems 8 and 9):

As one can see, the previous theorem explains, in the language of systems of premodels, why one can expect a strict reflection property in the case of set-valued models for a limit sketch.

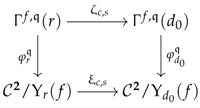

In Theorem 1, the assumption that the inclusion is an identity will be replaced, in Theorems 8 and 9, with the notion of effectiveness, which translates a variation of the concept of definability in (notice the parallelism with the concept of elimination of imaginaries given in Section 1.2). As will be shown in Theorem 7, this concept of definability becomes trivial if is taken to be equal to .

1.4. Results for Motivation 2

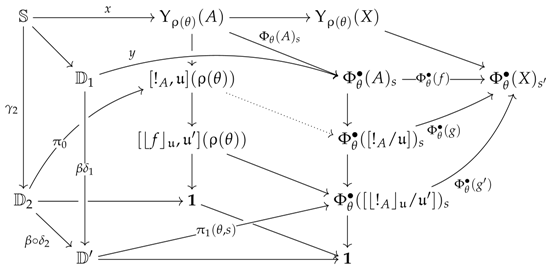

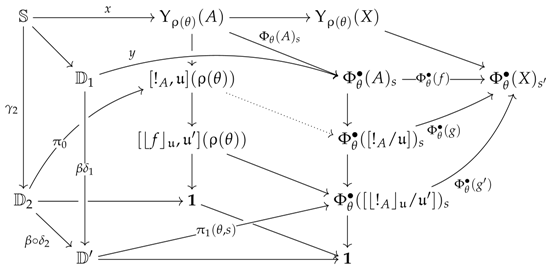

From the point of view of motivation 2, the present paper mainly focus on models for limit sketches in , so that we will mostly state our results from the perspective of these objects. This will nevertheless give an idea of what our theorems look like when generalised to other categories. The proof of the results stated below will be recapitulated in the conclusion of the present paper (Section 9).

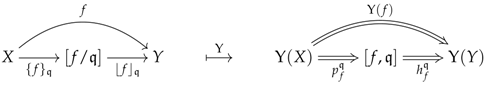

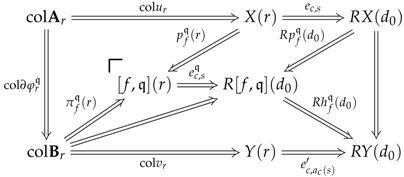

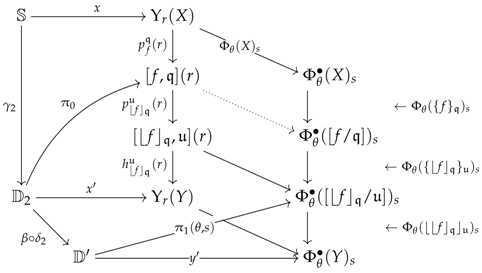

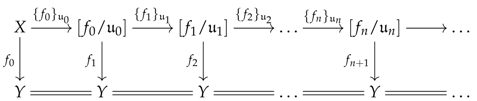

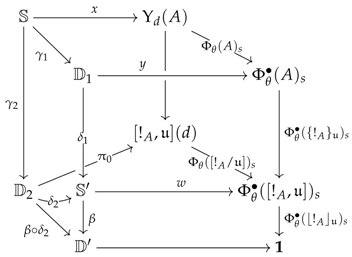

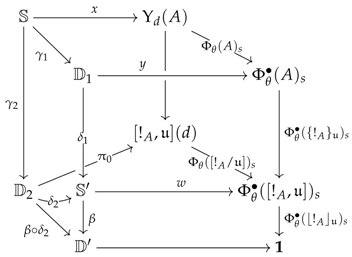

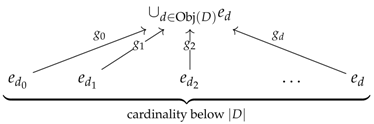

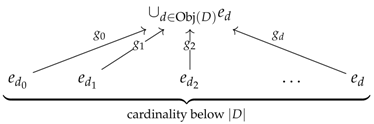

We now consider a limit sketch , where, for simplicity only, K is supposed to be a finite set of finite-limit cones. The proposition given below states that it is possible to construct the reflector of any presentation in a very specific way, which is not visible from Kelly’s construction [4].

Proposition 1.

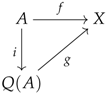

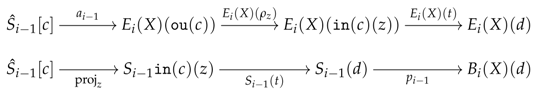

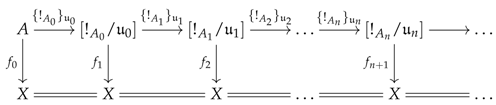

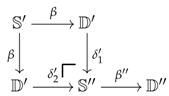

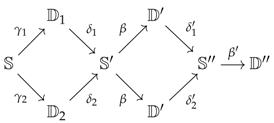

For every presentation X in and ordinal , there exist a pair of objects and and an epimorphism such that the reflector of X for the theory is given by the transfinite composition of the following sequence of arrows in :

In addition, the mappings and are functorial and the arrow is natural in X.

Of course, one could argue that the map coming from Kelly’s construction can be factorised into an epimorphism and a monomorphism , so that we might recover the previous form, but it is not obvious whether can be decomposed into a functorial sum in , mainly because the quotients that acts on might prevent from doing so. In fact, there is a much stronger way to assess the difference between Kelly’s construction and the previous one, which is given below.

Proposition 2.

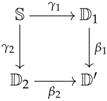

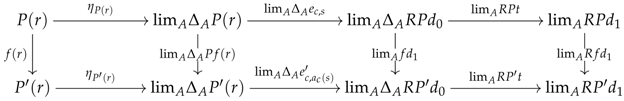

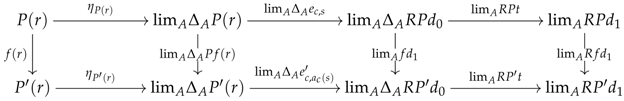

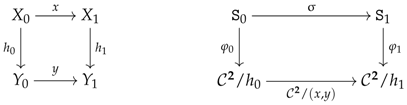

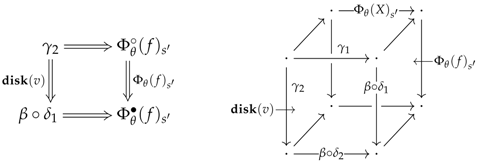

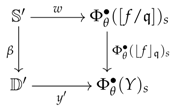

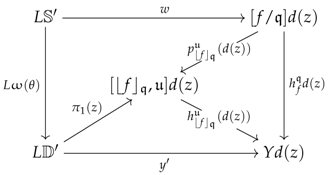

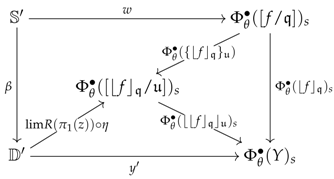

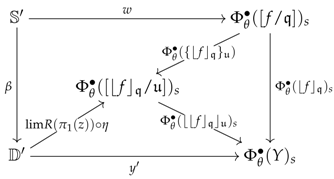

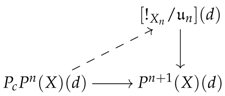

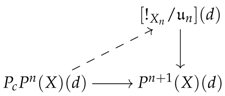

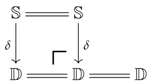

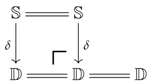

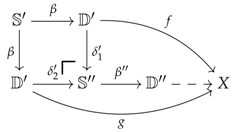

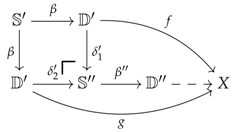

For every presentation X in , there exist a sequence of epimorphism , as given in Proposition 1, for which there is a natural transformation of transfinite sequences:

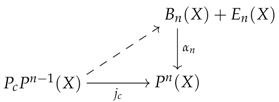

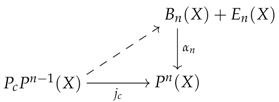

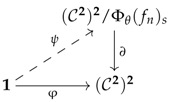

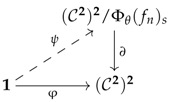

for which is the identity on X and if there exists a dashed arrow making the following triangle commute, then it must factorise through the canonical map and the object is a model for the limit sketch whenever :

for which is the identity on X and if there exists a dashed arrow making the following triangle commute, then it must factorise through the canonical map and the object is a model for the limit sketch whenever :

In other words, Kelly’s construction has too many quotients to be non-trivially lifted to the elimination of quotients, and if a lift exists, then it cannot be in the free part , which means that, at rank n, the free operations added to satisfy the theory are superfluous.

Even though the natural transformation is to identify free operations between each other, note that it cannot identify too much information either as the universal property of a reflector implies that the transfinite colimit of provides an isomorphism between the two underlying reflectors of X:

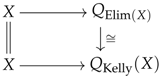

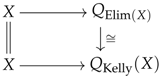

In fact, we will show that, in the case of models for a limit sketch, the so-called elimination of quotients takes the form given in Theorem 2, in which every cone c in K is again viewed as a natural transformation where is an object in D, is a small category, is the obvious constant functor picking out in D and is some functor .

Theorem 2.

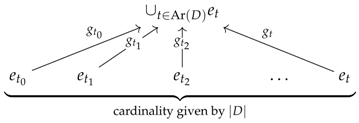

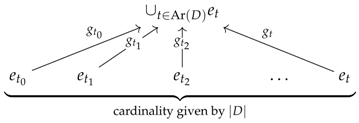

For every presentation X in , there exist a sequence of epimorphisms as given in Proposition 2, for which we will denote the coproduct object as a functor , such that:

- -

- and ;

- -

- is the left Kan extension of the functor:along the functor , where K is seen as a discrete small category;

- -

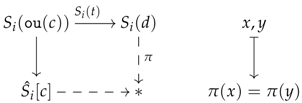

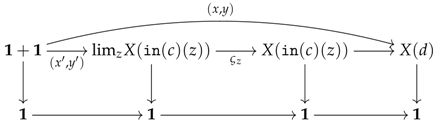

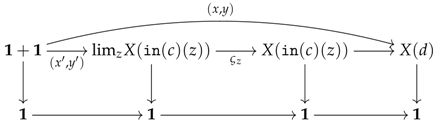

- the epimorphism is the quotient map making the following identifications:

- (1)

- for every object d in D, it identifies a pair if there exists a cone and an arrow in D for which the pushout of the canonical arrow along maps x and y to the same element;

- (2)

- for every object d in D, it identifies a pair where and if there exists a cone , an object z in the diagram of c and a morphism in D such that x and y can be lifted to a common element in via the span made of the following composites.

Even though we have only discussed the finite-limit case, all of the previous propositions hold for non-finite limit-sketches. In this case, the ordinal becomes the cardinality of the limit-sketch (see the end of Section 4.1) and the transfinite sequence of arrows needs to be defined such that is the transfinite colimits of all the arrows preceding the rank .

1.5. Road Map

The main results of the paper start to be developed from Section 4, while Section 2 and Section 3 give an account of various notations, conventions and technicalities. Specifically, Section 2 introduces a set of conventions meant to facilitate our notations while Section 7 focuses on a notion of smallness that will only be used in Section 7.

Even if Section 2 does not sound so attractive, the reader might want to skim through this section to get used to specific notations such as (Section 2.1); (Section 2.3); as well as (Section 2.5) and (Section 2.14).

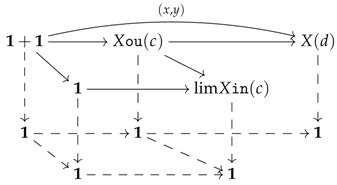

Section 3 defines a notion of smallness that generalises the usual one. Recall that one usually says that an object D in some category is small if for any functor (or, sometimes, any functor belonging to a certain classes of functors. This restriction generally arises in non-accessible categories such as in the category of topological spaces). Defined from the ordinal category to , say , the following canonical map is a bijection:

On the other hand, the smallness condition defined in Section 3 would be more of the following type. The property is now centred on the functor F and not on the object D any more; we then consider a set of objects G in and say that a functor is G-convergent if the following canonical map is a bijection for every object :

The reason for this change is that the image will not always be a colimit of the form .

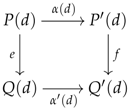

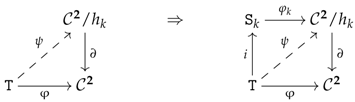

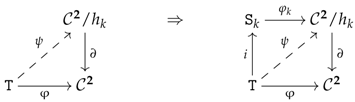

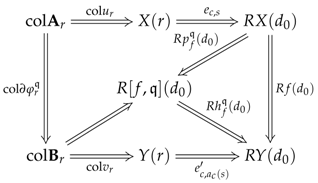

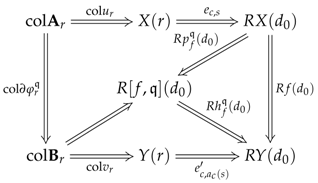

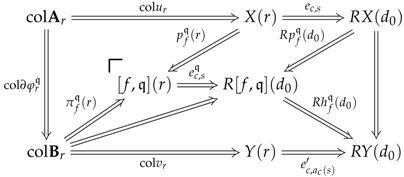

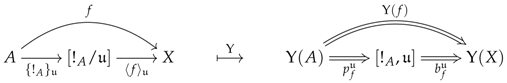

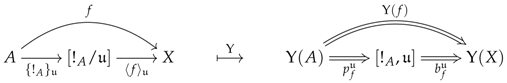

Then comes Section 4, in which is defined the notion of system of premodels. The difference with the simplified version given in Section 1.3 and that of Section 4 is that the canonical map is now constructed from various parts of the system of premodel structure, so that it is now of the form where R is a right adjoint endofunctor on . This right adjoint R will often be an identity functor in this paper, save for -spectra, in which case it will be equal to the loop space functor . In the future, the functor R will however take multiple forms.

Section 5 and Section 6 work together to formalise the idea of algebraic structure associated with a quotient. Recall that completing a presentation with operations usually requires the adding of free operations along with certain quotients. In our case, the free structure will be added to the presentations, but the quotient structure will be resolved in a separate object (see Section 6.7). The term resolved here refers to the concept of resolution developed in [28], which should be viewed as a way of passing from what looks like a set to a higher dimensional structure, such as category or a quotient map .

The purpose of Section 5, alone, is to give a theoritical generalisation of Quillen’s small object argument [8] while Section 6 focuses on applying the formalism of Section 5 to systems of premodels.

The difference between our argument and Quillen’s one is that one does no longer consider strict pushouts at every step and the lifts meant to be produced by these pushouts only commutes in the subsequent steps. These differences arise for two reasons. The first one is the desired elimination of quotients and the second one is due to the fact that the pushouts used in the usual argument do not necessarily commute with the right adjoints (including the limits) involved in the construction of the object .

To be able to formalise the previous ideas, we will introduce the concept of tome, whose goal is to gather all the squares that one would like to force to admit a lift through the small object argument. This will take the form of a functor , where h is an object in the arrow category . Note that this tool will mainly find its use in the way the category is encoded.

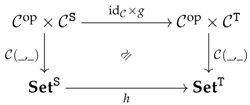

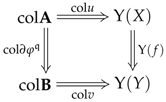

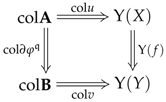

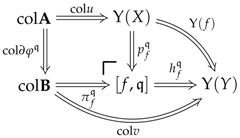

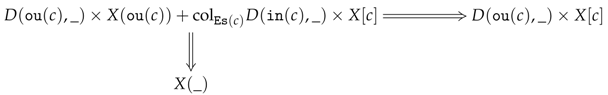

Specifically, in Section 6, this category will be discrete and will take the form of a coproduct of what could look like two left Kan extensions:

The left-hand sum will allow us to parameterise all those squares that are to force the adding of the structural information to the presentations while the right-hand sum will allow us to handle all of the quotients that the adding of this information is supposed to generate. Note that the rightmost sum of is only meant to quotient out what has been added at a previous step, leaving free the information added by the current leftmost sum and thus producing the elimination of quotients discussed in Section 1.4. All the data needed to talk about an elimination of quotients such as , , , , , (and some more) will be gathered into the notion of constructor (see Section 6.4). Remarks 11 and 13 might be helpful in seeing what all those left Kan extension-like constructions actually parameterise.

Finally, the small object argument is carried out in Section 7 where the smallness condition is used to prove the usual lifting properties. The universal property satisfied by our construction is discussed in Section 8 via Theorems 9 (existential part) and 8 (uniqueness). The latter mainly focus on the properties required to prove Theorem 2, whose proof is recapitulated in the conclusion (see Section 9.2).

1.6. Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Steve Lack and the referees for comments that allowed the improvement of the earlier versions of this text. I would also like to thank the members of the Australian Category Seminar for various remarks regarding the content of this paper.

2. Background, Notations and Conventions

2.1. Ordinals

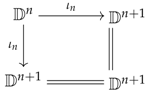

Any ordinal will be identified with the preorder category it induces. For every ordinal , the inclusion functor will be denoted by . For convenience, the preorder category of one and two objects will be denoted by and , respectively. We shall also use the notation to denote the least infinite ordinal.

2.2. Wide Subcategories

Let be a category. A subcategory will be said to be wide if the inclusion functor is surjective on objects. Put simply, this means that contains all the objects of .

2.3. Limits and Colimits

For every category and small category D, the obvious functor mapping an object to the pre-composition of with the canonical functor will be denoted by . For convenience, the category will often be identified with the category . If they exist, the left and right adjoints of will be denoted by and , respectively. Recall that the images of these two functors are understood as the colimits and limits of over D, respectively. As usual, in the case where the functor exists, the category will be said to be complete over D. Similarly, the category will be said to be cocomplete over D when the functor exists.

Proposition 3.

If a category is complete (resp. cocomplete), then so is for any small category D where the limits (resp. colimits) are defined objectwise in .

Proof.

Suppose that is complete. For every object d in D, the restriction functor mapping X to has a right adjoint whose images are given by the Right Kan extensions along the functor picking out d [29]. This implies that commutes with limits. By duality, the other statement regarding colimits follows. ☐

2.4. Cardinality

Let A be an object in . The cardinality of A is the least ordinal such that there is a bijection between A and . In ZFC, the axiom of choice ensures that the cardinality of a set A always exists, which will be denoted by .

For any small category D, the cardinality of D is the cardinality of the following coproduct of sets, where is the set of objects of D:

The cardinality of D will be denoted by . Below is given a well-known result on the commutativity of limits and colimits.

Proposition 4.

For every small category D and limit ordinal , the canonical natural transformation valued in over is an isomorphism.

Proof.

See Appendix A. ☐

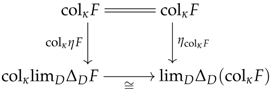

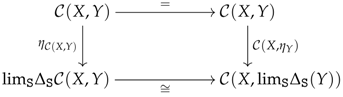

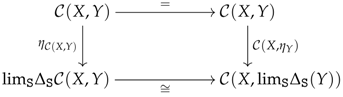

Similarly, for every complete category and small category D, the functor commutes with colimits (see Proposition 3). In fact, it follows from Proposition 4 that the unit of the adjuncion commutes with colimits in as stated in the next proposition.

Proposition 5.

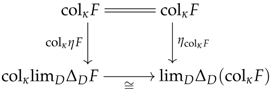

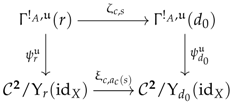

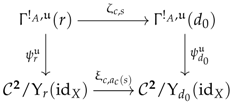

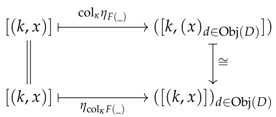

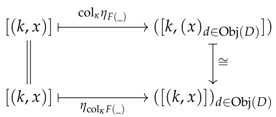

For every small category D and limit ordinal , denote by the letter η the units of the two adjunctions in and . The following diagram of canonical arrows in commutes for any functor :

Proof.

See Appendix A. ☐

2.5. Universal Shiftings

Let be a functor between small categories. The pre-composition with i induces an obvious functor . Mostly for convenience, the composition of this functor with the colimit functor will later be denoted by . The obvious canonical natural transformation will be called the universal shifting along i. Similarly, the composition of the functor with the limit functor will be denoted by .

2.6. Right Lifting Property

Let be a category and be a class of arrows in . The class of arrows of that have the right lifting property (abbrev. rlp) with respect to the arrows of will be denoted by .

2.7. Sequential Functors

Let be some ordinal and be a category. A functor will be said to be sequential if for any limit ordinal in , the object may be identified with the colimit of the functor such that, for every ordinal in , the morphism corresponds to the arrow of the universal cocone of associated with .

Proposition 6.

If a morphism has the rlp with respect to every arrow for every , then f belongs to .

Proof.

It is straightforward to show that if a morphism f has the rlp with respect to two composable arrows i and j, then it has the rlp with respect to the composition . A direct generalisation to the transfinite case shows the proposition. ☐

2.8. Limit Sketches

A limit sketch is a small category equipped with a subset Q of its cones (Recall that these are, by definition, natural transformations of the form in where A is a small category, U is a functor and d an object in , called the peak). The cones in Q will be said to be chosen. A model for a limit sketch in a category is a functor that sends the chosen cones in Q to universal cones (‘Universal’ here means that the cone, say , defines a limit of the functor ) in . The models of a limit sketch in define the objects of a category whose morphisms are natural transformations in over . For any limit sketch , the category of models for in will be denoted by .

Example 1 (Limit sketc for monoids).

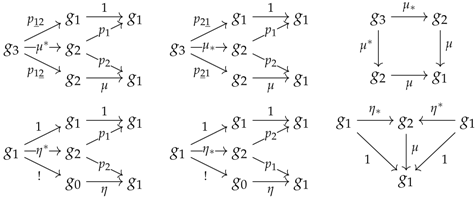

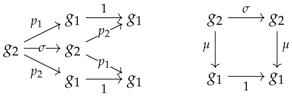

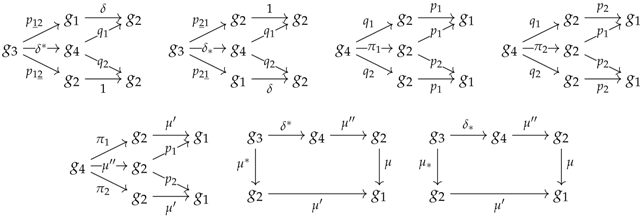

The category of monoids in may be defined as a category of models for a certain limit sketch . The underlying small category of is freely generated over a set of arrows and quotiented by commutativity relations. Specifically, the category has four objects , , and , where is called the underlying object of the sketch, and a set of arrows as follows, where the identities have been forgotten:

The commutativity relations are given by the diagrams:

while the chosen cones are given by the trivial cone, of peak , defined over the empty category and the following spans:

while the chosen cones are given by the trivial cone, of peak , defined over the empty category and the following spans:

The astute reader might have noticed that μ and η stand for the multiplication and unit of the monoid structure. It will come in handy to denote the preceding limit sketch by . Note that other limit sketches can give rise to the same models, so that the previous limit sketch is only an example among other possible presentations of the theory of monoids.

Example 2 (Limit sketch for commutative monoids).

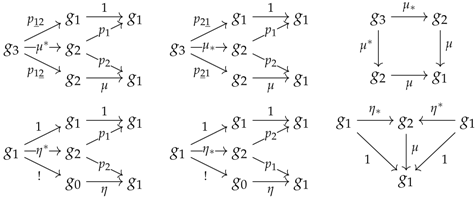

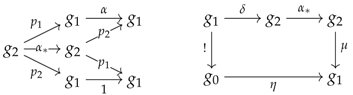

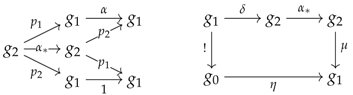

It is possible to add one more arrow and two diagrams to the limit sketch so that the category of models associated with the resulting limit sketch, say , is that of commutative monoids. Precisely, this would imply the adding of an arrow that makes the following diagrams commute:

Example 3 (Limit sketch for abelian groups).

It is also possible to add three more arrows and two diagrams to the limit sketch so that the category of models associated with the resulting limit sketch, which will later be denoted by for the notations given below, is that of abelian groups. Precisely, this would imply the adding of three arrows , and that makes the following diagrams commute:

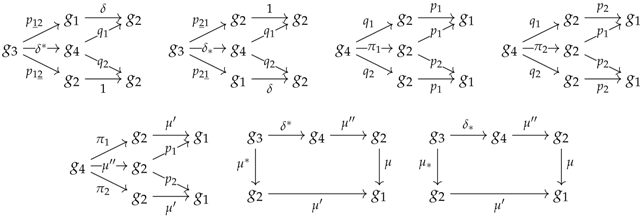

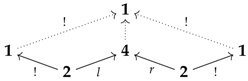

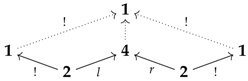

Example 4 (Limit sketch for rings).

By definition, the subcategory of generated by , , , ⋯, and ! is also included in . The pushout of and along these underlying inclusions provides a certain limit sketch that contains five objects and all the arrows and cones appearing in and ; the associated limit sketch combines the structure of a monoid with the structure of a commutative monoid. One thus recovers the theory of rings if one adds an object , a chosen cone and the following arrows and commutativity relations to :

The resulting limit sketch then defines a sketch for which the models are rings. The limit sketch to which the identity morphism is added to the set of chosen cones—when seen as a trivial cone—will later be denoted by .

2.9. Subfunctors

Let D be a small category and be a functor. A subfunctor of F is a functor such that (1) for every object d in D, the inclusion holds and (2) for every morphism in D, the function is the restriction of along the respective inclusions of the domain and codomain.

2.10. Overcategories

Let be a category and X be an object in . The obvious functor mapping an arrow in to the object A in will be denoted by ∂.

Remark 1.

Let be a small category. Any functor may be seen as a natural transformation in over of the form . The converse is also true.

Let now be a functor. It will come in handy to denote by the obvious functor on satisfying the following mapping rule on the objects:

2.11. Covering Families

Let D be a small category and d be an object in D. A covering family on d is a collection of arrows in D. For every morphism in D, we shall speak of the pullback of S along f to refer to a collection of arrows where the arrow is a pullback of along f. Also, note that every morphism gives rise to a family . This last operation is used to define a more complex operation on S as follows. For every , take a covering family on . We will denote by the covering family on d obtained by the disjoint union of families for every .

2.12. Grothendieck Pretopologies

Let D be a small category. A Grothendieck pretopology on D consists, for every object d in D, of a collection of covering families S on d such that:

- (1)

- (Stability) for every arrow in D, the pullback exists in ;

- (2)

- (Locality) for every and in , the covering family is in ;

- (3)

- (Identity) for every object d in D, the singleton is in .

Such a collection will usually be denoted by J. A category D equipped with a Grothendieck pretopology J on D will be called a site.

Remark 2.

Every covering family on an object d in may be seen as a functor if A is seen as a discrete category. It follows from the stability and locality axioms that this functor extends to a product-preserving functor where is the completion of A under products. This functor will be called the stabilisation of S.

2.13. Families

For any category , the notation will be used to denote the category whose objects are pairs where S is a discrete category and F is a functor and whose morphisms are given by pairs where a is a functor and is a natural transformation .

2.14. Bounded Diagrams

Let D be a small category, d be an object in D and be a category. We will denote by the category whose objects are triples where P and Q are functors and e is an arrow in and whose morphisms, say , are given by pairs of natural transformations of respective forms and making the following square commute:

Note that is also a functor category where is the smallest subcategory of consisting of the two copies of D and the arrow linking the two copies of d.

3. Convergent Functors

This section aims to define the notion of convergent functor, which is to replace the notion of “small object” that is usually used in transfinite constructions.

3.1. Emulations

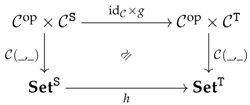

Let and be two small categories and be a category. A pair of functors and will be called an -emulation in if it is equipped with a natural isomorphism as follows:

In terms of an equation, the previous diagram means that is equipped with a natural isomorphism (in the variables , and ) as follows:

Example 5.

Let be a small category and be a category. Take g to be the identity functor and h to be the identity functor . By definition, the pair is a -emulation.

Example 6.

Let be a functor between small categories and be a category. Take g to be the pre-composition functor induced by U and h to be the equivalent version of g in . It suffices a few lines of calculation to show that the following isomorphism holds, which implies that the pair defines an -emulation:

Example 7.

Let be a small category and be a category. Take g to be the functor and h to be the functor . It follows from Example 6 that the pair is a -emulation:

Example 8.

Let be a small category and be a category complete over . Take g to be the limit functor and h to be the limit functor . It is a well-known fact following from Yoneda’s Lemma that the pair is an -emulation.

Example 9.

Let be a small category and be a category complete over . We will denote by η the unit of the adjunction valued in any category. Now, take g to be the obvious functor mapping an object X in to the arrow in and h to be the equivalent version of g in the category (which is complete over ). It follows from Yoneda’s Lemma that the following diagram commutes, which implies that the pair is an -emulation:

Example 10.

Let be a small category. For this example, we shall additionally need a small category A together a cone in . Let now denote a complete category over A. The unit of the adjunction in will be denoted by η. Now, to define our emulation, take g to be the obvious functor mapping a functor to the arrow:

in and h to be the equivalent version of g in the category . It follows from Yoneda’s Lemma that the pair is an -emulation. Specifically, the isomorphism associated with the pair may be deduced from the isomorphisms involved in Examples 6, 8 and 9.

Example 11.

Let be a small category. For this example, we shall need a small category A together a cone in . Let now denote a complete category over A. The unit of the adjunction in will be denoted by η. Now, to define our emulation, take g to be the obvious functor mapping an object in to the arrow:

in and h to be the equivalent version of g in the category . It follows from the isomorphisms involved in Examples 7, 8 and 10 that the pair is an -emulation.

3.2. Cocontinuous Emulations

Let and be two small categories, be a category and be a limit ordinal. An -emulation in will be said to be κ-cocontinuous, if for every object , the functor preserves colimits over .

Example 12.

Since identity functors preverse colimits, the pair of Example 5 is a κ-cocontinuous -emulation for every limit ordinal κ.

Example 13.

Consider the same context as that used in Example 6. Since is cocomplete over any small category D, the colimits of are componentwise colimits, which means that for every functor , the following isomorphism holds for every :

This directly implies that the functor preserves colimits, which shows that the -emulation is κ-cocontinuous for every limit ordinal κ.

Example 14.

It follows from Example 13 that the -emulation of Example 7 is κ-cocontinuous for every limit ordinal κ.

Example 15.

Consider the same context as that used in Example 8 and suppose to be given a limit ordinal κ satisfying the inequality . It directly follows from Proposition 4 that the functor preserves colimits over κ. This shows that the -emulation is κ-cocontinuous.

Example 16.

Consider the same context as that used in Example 9 and suppose to be given an limit ordinal κ satisfying the inequality . It follows from Proposition 5 that the functor preserves colimits over κ. This shows that the -emulation is κ-cocontinuous.

Example 17.

By using the cocontinuity involved in Examples 15 and 16, we may show that the -emulation is κ-cocontinuous for any limit ordinal κ satisfying the inequality .

Example 18.

By using the cocontinuity involved in Examples 13, 15 and 16, Example we may show that the -emulation is κ-cocontinuous for any limit ordinal κ satisfying the inequality .

3.3. Convergent Functors

For any class of objects of , a functor will be said to be -convergent in if for every object in , the following canonical function (obtained by homing) is an isomorphism in :

If the class turns out to be a singleton , the functor will more explicitly be said to be -convergent.

Remark 3.

One of the useful implications of the previous definition is that if a functor is -convergent in , then for every object and morphism in , there exist an ordinal and a morphism making the following diagram commute in :

Let now and denote two small categories and be a functor. A functor will be said to be unimorly G-convergent in if for every object s in and object t in , the following canonical function is an isomorphism in :

In other words, the evaluation of F at an object s in is -convergent.

Lemma 1.

Let and be two small categories such that and be a category. Let be a functor and consider a uniformly G-convergent functor in . For every cocontinuous -emulation , the composite functor is G-convergent in .

Proof.

The following series of natural isomorphisms proves the statement:

This last isomorphism shows that is G-convergent in . ☐

Example 19.

Applying Lemma 1 to the -emulation of Example 5 implies that if a functor is uniformly G-convergent in and the inequality holds, then the functor is G-convergent in .

Example 20.

Applying Lemma 1 to the -emulation of Example 18 implies that if a functor is uniformly G-convergent in for some functor and the inequality holds, then the functor mapping an ordinal n in to the following composite arrow in is G-convergent in :

Remark 4.

It follows from Lemma 1 that if a functor is uniformly G-convergent in , then is -convergent in . Specifically, this follows from the fact that commutes with hom-sets (see Example 14) and the following series of isomorphisms:

4. Models for a Croquis

This section defines the notions of premodel and model for which we want to construct the localisation. We start with the type of theory on which the models are defined.

4.1. Croquis

Let D be a small category. Recall that a cone in D over a small category A consists of two functors and and a natural transformation . When such a cone is called c, the functor will be denoted by , the functor will be denoted by and the small category A will be referred to as the elementary shape of c and denoted by .

Definition 1.

A croquis category (or croquis) in D consists of a set K of cones in D and a functor (where K is seen as a discrete category) called the regular output.

A croquis as above will be denoted by a triple and sometimes shortened to the pair when the ambient category D is obvious.

Convention 1.

For every croquis , the operation induces a function from K to . Alternatively, this may be seen as a functor . If the functor is equal to , then the croquis will be denoted by or K and the functor will be said to be trivial.

Example 21 (Arrow categories).

Let D be a small category, be a subcategory of D and be some given functor. The set of arrows of defines an obvious set of cones of elementary shape in . However, because is a subcategory of D, we shall in fact see as a set of cones specifically in D. The croquis (in D) made of and the regular output mapping any arrow in to the object will later be denoted by .

Example 22 (Spectra).

Let denote the wide discrete subcategory of the ordinal category ω and denote the full subcategory of restricted to positive ordinals. Let be the predecessor operation . The croquis defined by will later be used to characterise Ω-spectra.

Example 23 (Sketches).

Any limit sketch defines an obvious croquis where K stands for the set of chosen cones and where the associated regular output is the trivial one.

Example 24 (Grothendieck’s pretopologies).

Let J denote a Grothendieck pretopology on a small (opposite) category . A covering family in may be seen as a cone of the form in D over A. If one denotes by the stabilisation of C (see Remark 2), this cone gives rise to another cone over . Equipping D with the set of these latest cones, say , gives rise to an obvious croquis .

Example 25 (Flabby pretopologies).

Let J denote a Grothendieck pretopology on a small (opposite) category . The croquis that will later give rise to flabby sheaves and the Godement resolution is the union of the two croquis and . Precisely, this croquis consists of the union of the two sets of cones and and the trivial regular output.

Example 26 (Segal croquis).

Let Δ denote the category of non-zero finite ordinals and preserving-order functions, which is known as the simplex category. Denote by the wide subcategory of Δ whose arrows are injective functions and, for every object , denote by the composition of the functor (see Section 2.10) with the obvious inclusion . The Segal croquis of is of the form (for a trivial regular output) where:

- (i)

- contains, for every object , the cone , defined over , that stems from the dual transformation described in Remark 1 for the inclusion functor ;

- (ii)

- contains, for every object , the cone given below (expressed in Δ as a cocone), where, if one denotes , and :

- (1)

- is the function with the mapping rules and ;

- (2)

- is the function with the mapping rule ;

- (3)

- is the function with the mapping rule .

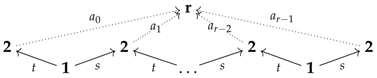

This croquis will be denoted by .

Example 27 (Complete Segal croquis).

Let Δ be the simplex category. The complete Segal croquis of is given by its Segal croquis to which is added the unique cone whose peak is the ordinal and whose diagram in Δ is given, below, underlying the cocone of dotted arrows, where, if one denotes and :

- (1)

- is the function with the mapping rules and ;

- (2)

- is the function with the mapping rules and ;

The induced cone in will be denoted by as it is meant to describe the set of isomorphism structures relative to the natural categorical (or nerval) structure of . The resulting croquis will be denoted by .

We shall speak of an elementary shape of a croquis to refer to the elementary shape of one of its cones. Because K is a small category, the class of elementary shapes of is a set, which will be denoted by . The cardinality of a croquis is then given by the cardinal of the coproduct of every small category in :

4.2. Premodels

Let be a croquis and be a category. For any endofunctor , denote by the category whose objects are triples where (1) P is a functor , (2) S is a functor (To not say a ‘function valued in a category’. Such a simplification will be common later on) and (3) e denotes a collection of arrows in for every and and whose morphisms, say of the form , are pairs where f and a are two natural transformations of respective forms and making the following diagram commute for every and :

The objects of will be called the R-premodels for . For convenience, the category will sometimes be denoted as when is trivial and as when R is also an identity.

Example 28 (Premodels).

The category of premodels for a sketch to a category corresponds to the full subcategory of whose objects are such that the images of S are equal to and the morphism is an identity for every . This subcategory is isomorphic to .

Example 29 (Presheaves).

The category of presheaves over a site corresponds to the full subcategory of whose objects are such that the images of S are equal to and the morphism is an identity for every . This subcategory is isomorphic to .

Example 30 (Prespectra).

If denotes the loop space functor on the category of pointed topological spaces and denotes the predecessor operation on , then the category of prespectra is the full subcategory of whose objects are such that the images of S are equal to . This subcategory will be denoted by .

Example 31 (Pre-localised rings).

Let denote the category of sets and be the limit sketch defined in Example 4. The category of ‘pre-localised rings’ is defined as the full subcategory of the category whose objects are such that (1) is a model for ; (2) the image of above the cone is equal to a subset of while its images above all the other cones are equal to and (3) the morphism is given by:

- -

- the right multiplication map for every if ;

- -

- the identity morphism otherwise.

This subcategory will be denoted by .

Example 32 (Pre-Segal spaces).

Let denote the category of topological spaces and continuous functions. The category of pre-Segal spaces is the category of simplical topological spaces; it is given as the full subcategory of whose objects are such that the images of the functor S are equal to and the morphism is an identity for every . Thecategory of pre-complete Segal spaces is defined similarly by replacing with .

Definition 2.

Let D be a small category and be a category. For any given endofunctor , a category of R-premodels is a subcategory of the category .

Example 33.

Premodels for a sketch, presheaves on a site, prespectra, pre-localised rings and pre-Segal spaces are examples of such categories (see the previous examples).

4.3. Models

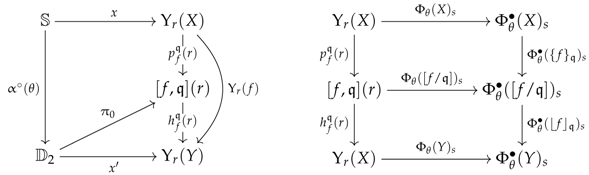

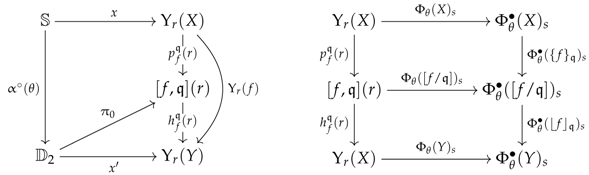

Let D be a small category, be a croquis in D and be a complete category over the elementary shapes of K. Suppose to be given a right adjoint . The first goal of this section is to define a functor for every cone . In this respect, for every cone c in K of the form , for which we shorten the notation to the symbol r, the functor maps any premodel to the family taking any to the following composite arrow in :

For every morphism of R-premodel of the form , the image morphism is given, for every , by the following morphism in :

Definition 3 (System of premodels).

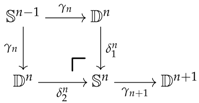

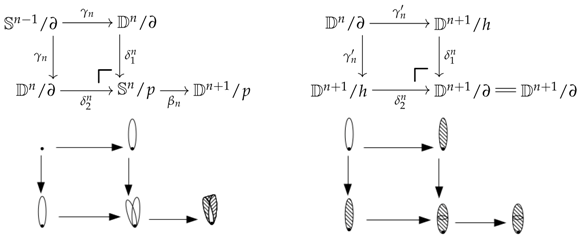

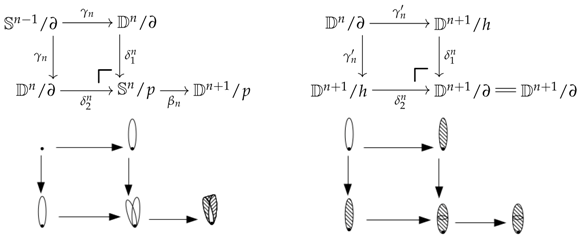

A system of R-premodels consists of (1) a croquis ; (2) a category that is complete on the elementary shapes of K and admits a terminal object; (3) a category of R-premodels where R is a right adjoint and (4), for every cone , a set of commutative squares in , called the diskads (see left diagram, below) equipped with a pushout in (see right diagram, below):

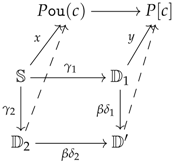

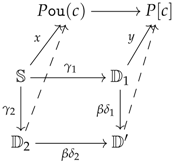

The collection consisting of all the sets will usually be denoted by . A system of R-premodels will be denoted as a 4-tuple and said to be defined over D in . The diagrams used in Definition 3 can more efficiently be described as a colimit sketch in (i.e. diagram equipped with colimits) of the following form:

This type of colimit sketch will be called a vertebra and denoted by the symbols . For such a vertebra, it will come in handy to refer to the arrows , , and as the seed, coseed, stem and trivial stem, respectively. Finally, the left adjoint of will conventionally be denoted by L.

Definition 4 (Model).

An R-premodel in a system of R-premodels will be said to be anR-model if, for every cone , every component of the arrow in has the right lifting property with respect to all the diskads of when these are seen as arrows in with respect to the notations of Equation (3):

Example 34 (Models for a sketch).

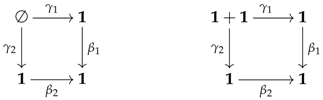

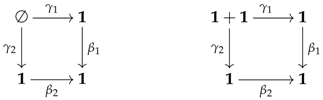

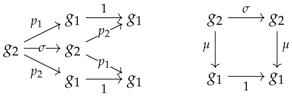

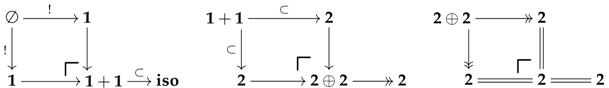

For every limit sketch , define the system of premodels consiting of the croquis K (see Example 23); the associated category of premodels and, for every cone c in K, the set made of the following vertebrae in :

The -models of such a system correspond to the models for the sketch .

Example 35 (Sheaves).

For every site , define the system of premodels consiting of the croquis (see Example 29); the associated category of premodels and, for every cone c in , the set made of the vertebrae given in Equation (4). The -models of such a system correspond to the sheaves over .

Example 36 (Flabby sheaves).

For every site , define the system of premodels consiting of the croquis defined in Example 25; the functor category and:

- (i)

- for every cone c in , the set made of the vertebrae given in Equation (4);

- (ii)

- for every cone c in , the set made of the leftmost vertebra of Equation (4) only.

The -models of such a system correspond to the sheaves over whose morphisms over any arrow in D are surjective, namely the flabby sheaves over .

Example 37 (Sheaves in categories).

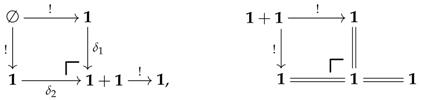

For every site , define the system of premodels consiting of the croquis (see Example 29); the associated category of premodels and, for every cone c in , the set made of the following vertebrae for the obvious choices of morphisms, where:

- (1)

- is a terminal category;

- (2)

- is the free living isomorphism category (i.e., two objects, one isomorphism);

- (3)

- is the free living arrow category (i.e., two objects, one arrow);

- (4)

- is category made of two objects and two parallel arrows between them.

The -models of such a system correspond to those ‘sheaves’ for which the sheaf condition is not a bijection but an equivalence of categories.

Example 38 (Strong stacks).

For every site , define the system of premodels consiting of the croquis defined in Example 25; the functor category and:

- (i)

- for every cone c in , the set made of the leftmost vertebra of Equation (4) when seen in (instead of ) and the rightmost two vertebrae of Equation (5);

- (ii)

- for every cone c in , the set made of the leftmost vertebra of Equation (5) only.

The -models of such a system correspond to the strong stack (see [23]). The strong stacks completion constructed in ibid corresponds to a special case of the general construction given in this paper.

Example 39 (Strong stacks up to homotopy).

For every site , define the system of premodels consiting of the croquis defined in Example 25; the functor category and:

- (i)

- for every cone c in , the set made of the vertebrae given in Equation (5);

- (ii)

- for every cone c in , the set made of the leftmost vertebra of Equation (5) only.

The -models of such a system may be identified to the strong stacks of [23] up to the notion of homotopy defined thereof.

Example 40 (Segal spaces).

Define the system of premodels consisting of the croquis defined in Example 26; the category of pre-Segal spaces , which is included in and:

- (i)

- for every cone c in , the set of obvious vertebrae induced by the diskads given in Equation (6), where:

- -

- n runs over the natural numbers;

- -

- the object is the topological n-disc;

- -

- the map is the obvious hemisphere inclusion;

- (ii)

- for every cone c in , the set of Vertebrae (7), where n runs over the positive integers and:

- -

- the object is the topological -sphere;

- -

- the maps between the different objects are induced by the obvious inclusions;

The -models of such a system correspond to the Segal spaces in (see [25] for a definition enriched in simplicial sets).

Example 41 (Complete Segal spaces).

Define the system of premodels consisting of the croquis defined in Example 27; the category of pre-complete Segal spaces , which is included in , and:

- (1)

- for every cone c in that is in fact in , the same set of vertebrae defined in Example 40;

- (2)

- for the cone (see Example 27), the set of vertebrae of the form (7) for every positive integer n.

The -models of such a system correspond to the complete Segal spaces in (see [25] for a definition enriched in simplicial sets).

Example 42 (Spectra).

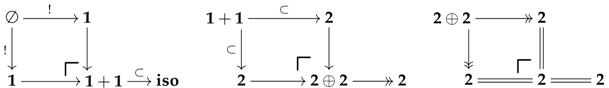

For the loop space functor , define the system of Ω-premodels consiting of the croquis defined in Example 22; the category of prespectra and, for every cone c in , the set of vertebrae of pointed spaces defined in Diagram (8), where n is a positive number and:

- -

- where the object is the quotient of the -sphere by itself (i.e., a point);

- -

- where the object is the quotient of the n-disc by its boundary;

- -

- where the object is the quotient of the n-sphere by its equator;

- -

- where the object is the quotient of the -disc by its equator;

- -

- where the object is the quotient of the -disc by one of its hemispheres;

- -

- where the object is the quotient of the -disc by its boundary;

- -

- where the maps between the different objects are the obvious inclusions:

The Ω-models of such a system correspond to the Ω-spectra.

Example 43 (Localisation of rings).

Consider the system of premodels consisting of the croquis (see Example 31), the subcategory and, for the cone c in , the set made of the vertebrae given in Equation (4). The -models of such a system correspond to the rings P for which the map is invertible for every , or in other words those rings that are localised at their associated subset of elements S. Fields are particular examples.

Remark 5.

Many other examples could have been provided. Recall that it is common fact (see [27] (Lemma 7.5.1), [30] or [31] (Proposition 8)) that, in some nice model category , the notion of weak equivalence may be characterised via the type of right lifting property expressed in Example 4. For instance, Examples 40 and 41 on Segal spaces could have been extended to any nice cofibrantly generated model category, which need not be simplicial (contrary to usual practice). In fact, it is worth noting that the type of localisation described in the present article is an alternative to the usual simplicial Bousfield Localisation process (see [7]). On could also look at the type of localisation discussed in [32] (Corollary 8.8), which could be comprised in a more technical generalisation of the present work. Future work will also aim at generalising Example 37 to weaker functors in order to charactise the notions of -stack and strong -stack.

5. Narratives and the Small Object Argument

This section aims to introduce the small object argument that will be used for the construction of the localisation. The difference from that given below and the one defined by Quillen [8] is the notion of ‘degree’ coming along with the concept of narrative (see below). The degree is the key ingredient that allows us to obtain our so-called elimination of quotients.

| Notions | Descriptions | |

| Tome | A collection of commutative squares whose rightmost vertical arrows are all equal: this can be visualised as a ‘book’ whose pages are glued along a spine. The pages can satisfy certain compatibility relations. |  |

| Morphisms of tomes | Regular: relate the spine and the pages of two ‘books’ together. | |

| Loose: only relate the spines. | ||

| Oeuvre | An ordered collection of tomes related via loose morphisms; the theme is the common object towards which the spines of the books go to. | |

| Narrative of degree | An oeuvre that is equipped with sub-diagrams of its tomes, called the events, and choices of lifts for these sub-diagrams, called the viewpoints These lifts only ‘commute’ from the k-th book to the -th book. | |

5.1. Numbered Categories and Compatibility

In the sequel, the term numbered category will denominate any pair where is a category and is a limit ordinal. A small category will be said to be compatible with if (1) the category admits colimits over and (2) the inequality holds. By extension, a functor will be said to be compatible with a numbered category if its domain is compatible with .

5.2. Lifting Systems

Let us now define in formal terms what will later be seen as a set of generating cofibrations for our small object argument. Let be an numbered category. A lifting system in is a set J of objects of that are compatible with as functors.

5.3. Right Lifting Property

Let be an numbered category and J be a lifting system in . For every functor in J, the image of an object s in via will usually be denoted by . A morphism in will be said to have the right lifting property with respect to the system J if for any functor in J, the morphism has the rlp with respect to the arrow in . In the sequel, the class of morphisms of that have the right lifting property with respect to a lifting system J will be denoted by .

Example 44.

If J is a set of functors of the form picking out some objects of , then the preceding right lifting property corresponds to the usual one.

5.4. Tomes

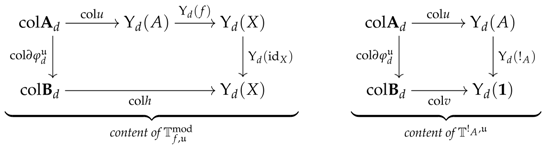

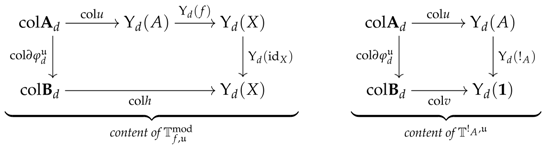

Let be a category. A tome in is a triple consisting of a morhism in , a small category on which admits all colimits and a functor . According to Remark 1 applied to the arrow category , a way of seeing a tome in is in the form of a cocone in over the functor . Because has all colimits over , the earlier cocone provides an arrow in after applying the adjunction property of on it. This latest arrow will be referred to as the content of . Note that for any functor , we may pre-compose the universal shifting induced by i (see Section 2.5) with the content of as follows:

The resulting arrow will later play a central role and be referred to as the content of along .

5.5. Morphisms of Tomes

Let be a category. A loose morphism of tomes from to is given by a morphism in . A regular morphism of tomes is given by a morphism in and a functor making the next right diagram commute:

The arrow symbol associated with loose morphisms will be denoted as . The category whose objects are tomes in and whose arrows are regular (resp. loose) morphisms of tomes will be denoted by (resp. ). For a fixed object Q in , the wide subcategory of that is restricted to the loose morphisms whose components are identities on Q will be denoted by .

5.6. Oeuvres and Narratives

Let be a numbered category and Q be an object in . An oeuvre of theme Q in is a functor lifting (This lifting is formal and is mostly justified by the definition of the morphisms given in Section 5.9) to along the obvious inclusion .

Convention 2.

In the sequel, the image of an inequality in via an oeuvre will be denoted by . For convenience, when l is successor of k in , the notations will be shortened to . For every object k in , the morphism will be denoted as an arrow while the image of the composite functor at an object s in will be denoted as .

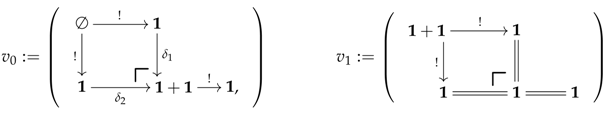

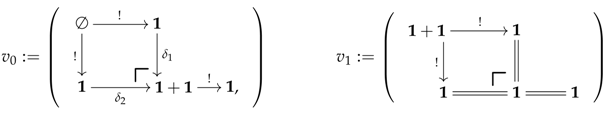

For every finite ordinal , a narrative of theme Q and degree δ in is an oeuvre of theme Q equipped with:

(1) (events) for every ordinal , a set , called the set of events at rank k, consisting of objects of that are compatible with as functors;

(2) (viewpoint) for every functor in the set , a lift for the commutative square (living in ) resulting from the pre-composition of the content of along with the arrow ; the square is therefore of the form in . The lift will later be referred to as the viewpoint at rank k along i.

Remark 6.

It follows from Convention 2 that the viewpoint at rank k along i mentioned in item (2) must be of the form .

Convention 3.

The functor induced by the sequence of arrows for every inequality in will be denoted by G and called the context functor.

Observe that any oeuvre and, a fortiori, any narrative as defined above provides a factorisation in as given below. This factorisation is that used for our small object argument:

Also, notice that the set of events induces an obvious lifting system , which will be denoted by .

5.7. Small Object Argument

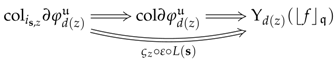

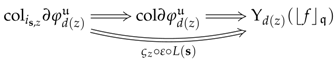

Let be a numbered category, Q be an object in and be a narrative of theme Q and degree . A lifting system J in will be said to agree with the narrative if for every ordinal and functor in J admiting a lift of along ∂ (see left diagram below), there exists a functor in whose composite with gives the lift (see right diagram below):

Proposition 7 (Small Object Argument).

Let J be a lifting system in agreeing with the narrative . If the context functor is uniformly -convergent in for every , then the morphism appearing in Equation (9) is in .

Proof.

The goal of the proof is to show that the morphism is in . To do so, let be a functor in J and consider any arrow . The proposition will be proven if the commutative square encoded by this arrow admits a lift. By assumption, the functor is uniformly -convergent in . It follows from Remark 4, taken from the viewpoint of Remark 3, and the fact that is limit (Recall that if is limit, then for every ordinal , the successor is also in for every ) that there exist an ordinal and an arrow factorising as follows:

Note that an application of the universal property of the adjunction on the leftmost arrow of Equation (11) provides an arrow in as follows (where the leftmost arrow, given below, is the unit of ):

According to Remark 1, Arrow (12) induces a functor , which makes the leftmost diagram of Equation (10) commute. Because the lifting system J agrees with the narrative , there must exist a functor making the right diagram of Equation (10) commute. This means, after re-applying the adjunction , that Equation (11) is in fact of the following form, where the leftmost arrow is precisely the content of the tome along :

It follows from the viewpoint axiom (see Section 5.6) satisfied by that the Composite admits a lift. This implies that the whole composite (13) admits a lift, which, a fortiori, implies that the arrow admits a lift. ☐

5.8. Strict Narratives

Let be a numbered category and Q be an object in . For any narrative of theme Q, recall that the set of events gives a collection of functors that induces a cocone under the category (see Section 5.6). A narrative of theme Q and degree will be said to be strict in if:

- (1)

- for every ordinal , the cocone induced by the elements of is universal in ;

- (2)

- it is equipped with a morphism factorising the content of into a pushout as follows;

- (3)

- for every functor in , the viewpoint along i is equal to the pre-composition of with the universal shifting along i as follows;

- (4)

- the context functor is sequential (see Section 2.7).

Proposition 8.

If a morphism is in (see end of Section 5.6) for every , then it has the rlp with respect to the arrow (see Diagram (9)).

Proof.

Let be a morphism that has the rlp with respect to the lifting system for every . For any , this means that it has the rlp with respect to the following arrow in , for every functor in :

It directly follows that f has the rlp with respect to the coproduct of these arrows over the set (seen as a discrete category), which may be identified to the arrow up to isomorphism as shown below:

It follows from classical facts that, since f has the rlp with respect to , it has the rlp with respect to any of its pushouts, and hence with respect to for any . It finally follows from Proposition 6 and the fact that the context functor is sequential that f has the rlp with respect to the arrow in . ☐

5.9. Morphisms of Oeuvres

Let be a numbered category. For every pair of oeuvres and , of respective themes Q and , a morphism of oeuvres from to consists, for every ordinal , of a regular morphism of tomes:

such that the underlying loose morphisms induce a morphism in the functor category (see Remark 7). The category whose objects are oeuvres for the numbered category and whose arrows are morphisms of oeuvres will be denoted by .

Remark 7.

The previous definition implies that all the arrows are equal to the same morphism for every . In addition, it forces the equality to hold in for every .

6. Constructors and Their Tomes

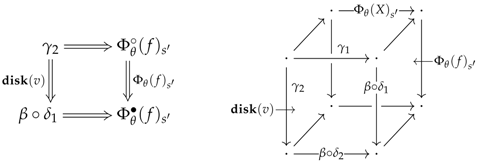

This section introduces the notion of constructor that allows one to associate systems of premodels with tomes. Constructors contain all the necessary information that permits the ‘elimination of quotients’. We will see that their definition already brings out what is meant to be analytic (or structural) and what is meant to be quotiented out. Even if they appear to comprise many components, the main goal of the items defined in Section 6.2 and Section 6.4 is to be able to define two sums whose forms look like the following type:

The hom-sets —which are defined in Section 6.4—are meant to ensure a certain functoriality (i.e., they are the monomials for a certain type of species [33]) while the hom-sets —which are defined in Section 6.2—are meant to contain the ‘squares’ that will enable us to perform our small object argument. In the sequel, I shall therefore try to give evoking names to the different parameters used to define these sums. In particular, one sum is to encode the structural data of our elimination of quotients while the other one is to encode the quotient acting on this data. To make the reader more confident with the items of Section 6.2 and Section 6.4, here is a preluding summary of the different notations used therein.

| 1st Hom | 2nd Hom | ||||||

| analytic sum | D | ||||||

| quotient sum |

6.1. Some More Notations

The following conventions are meant to ease the combinatorial description of a constructor and its associated tomes, which will be defined in Section 6.6.

Convention 4 (Vertebrae).

The diskad of a vertebra will be denoted by and seen as an arrow in . The other arrow in , which is induced by the ‘dual’ vertebra , will be denoted by and called the codiskad of v. Finally, the stem β and seed of v will be referred to by the notations and , respectively.

Convention 5 (Domains and codomains)

Let and be two categories and be a functor. In order to avoid too many notations in our reasonings, the image of an object X of in the arrow category will be denoted as . This implies that every morphism in gives a commutative diagram as follows:

Similarly, for every functor , we will denote by and the “source” and “target” arrows of the squares involved in the image of H.

Example 45.

For every vertebra v in as displayed in Equation (3), the arrow is equal to . Thus, when the reader reads in Section 6.4, where is a functor mapping any element in I to the diskad of a certain vertebra in , they should think of the seed of the so-called vertebra.

Convention 6 (Closedness).

Let , and be three categories. The image of any functor of the form will later be denoted as for any pair of objects in – instead of the usual notation .

Convention 7 (Families).

Let be a category. In the sequel, we will denote by the obvious functor mapping a pair to the functor . Also, mainly for convenience, the images of any object in at some will be denoted by . This means that the equation holds for every .

Convention 8 (Families of arrows).

Convention 5 will be extended to in the obvious way: for every functor , we shall denote by and the obvious functors mapping any object to the families and , respectively.

Convention 9.

Later on, I shall often identify a set with a discrete category and identify many functions with functors. The reason for this is that we shall pre-compose these functions with functors going from discrete categories to non-trivial categories, which, for their parts, should really be seen as functors. This convention should thus ease the back and forth between set theory and category theory.

6.2. Preconstructors

This section introduces the concept of preconstructor. This notion tries to capture what it takes to specify the data of a localisation. For instance, in Modern Algebra, localising a ring requires one to specify:

- ☆

- the underlying set that one wants to act on, which is here the set R;

- ☆

- the subset by which one wants to localise the ring;

- ☆

- the operation that one wants to inverse, which is here given by the S-indexed family of group morphisms defined by the mappings ;

- ☆

- the type of inversion one wants to see happening on the maps .

Regarding this last item, the inversion would, for instance, be expressed in terms of a bijection for the type of localisation used in Classical Algebraic Geometry, but it would be expressed in terms of a quasi-isomorphism in the category of unbounded chain complexes in Derived Algebraic Geometry.

To pass from the earlier description to the formalism of preconstructors, one can try to describe what a preconstructor would be for the previous list of items, so that we could make the following associations (also, see the structure below): the data would specify the object R while the data would give the subset S; the data , and would enumerate the maps with theirs domains R and codomains R (which would be required to be independent of the indices in S); and the data and would specify the type of inversion one wants to see happening. We now give a formal definition.

Let and be two categories and D be a small category. A preconstructor of type , let us call it , consists of a discrete category I together with:

- (a)

- two functors and , called the regulator and the localisor;

- (b)

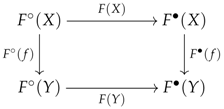

- three functors as given below, which satisfy the string diagram axioms given underneath them (or the equations given just after);The previous string diagrams amount to saying that the following equations hold in the functor “category” for every ;

- (c)

- two functors and , called the analysor and the quotientor, such that the image encodes the diskad of a vertebra of stem for every ;

As mentioned in the preamble of Section 6, a preconstructor contains all the information that is necessary to define the parametrising ‘squares’ on which we will run the small-object-argument algorithm. These so-called parameters will be presented either as families (see Definition 5) or as formal sums (see Definition 6) – both presentations being useful.

Definition 5 (Families).

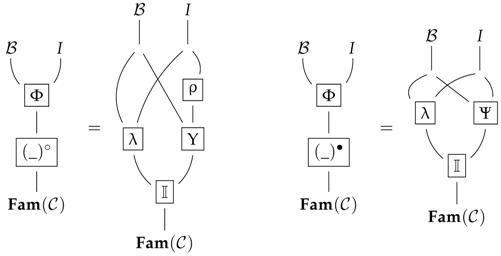

For any preconstructor as defined above, the analytic family of and the quotient family of are two functors and whose images are determined, for every arrow in and object , by the following mappings (or families) over :

Remark 8 (Concept of vertebra).

The relationship between the analytic family and the quotient family is established in item c) via the concept of vertebra. At this stage, this should suggest to the reader that the notion of vertebra subtly encompass both the idea of quotient—or coherence—via its stem and the idea of cellular structure—or ana-lysis—via its diskad.

Definition 6 (Species).

For any preconstructor as defined above, the analytic species of and the quotient species of are two functors and defined as follows, for every arrow in and object :

6.3. Preconstructor of a System of Premodels

Let be a system of R-premodels over a small category D in a category . The goal of this section is to associate any such system with a preconstructor of type . In this respect, define the set I to be the following leftmost disjoint sum:

Remark 9 (Encoding).

Any element θ in I may be presented as a pair where is a cone in K and v is a vertebra in .

By keeping the notational convention suggested by Remark 9, one defines the data of the preconstructor for the system of premodels as follows:

- (1)

- the regulator is given by the mapping ;

- (2)

- the localisor is given by the evaluation ;

- (3)

- the analysor is given by the mapping ;

- (4)

- the quotientor is given by the mapping ;

and because both equations:

hold for every , one may define the functor as the obvious functor satisfying the mapping on objects, so that the two associated functors and are defined as follows:

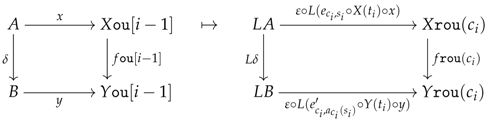

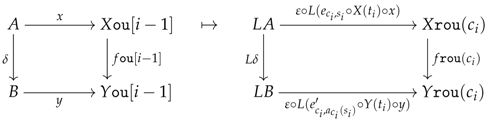

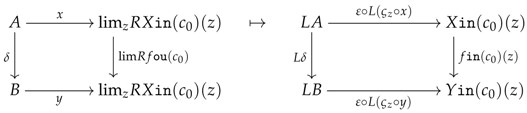

Remark 10 (Encoding).

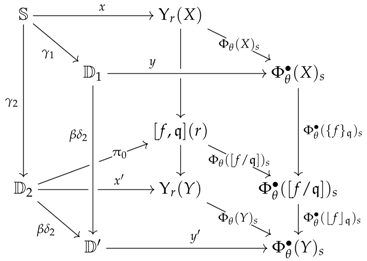

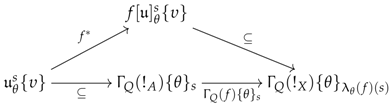

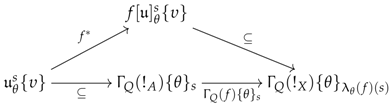

For every arrow in and element θ in I, the image of the analytic species contains the tuples (The symbol is, here, preferred to the plain letter s as it could be confused with the notation (in bold) or thought to be related to the notation , which is not the case. I shall sometimes use s instead of when no confusion is possible) where: is a cone in K; v is a vertebra in ; is an element in and is a commutative square in of the form given below, on the left, for the notation , which may also be seen as the right commutative cube in when viewed from the bottom-left corner:

Similarly, the image of the quotient functor contains the tuples where: is a cone in K; v is a vertebra in ; is an element in and is an arrow in for the notation .

6.4. Constructors

This section introduces the concept of constructor. In comparison to the informal introduction of Section 6.2, a constructor should be seen as a structure giving all the data that we need to describe the localisation of the ring R by a subset S in terms of freely-added tuples and relations acting on these.

Specifically, one usually constructs the localisation by freely adding tuples of the form , for every and , to the set R. These tuples are often denoted as quotients . Because S has not been supposed to be a multiplicative set, one would also need to specify tuples of the form for every and where . The equivalence relations defined on the pairs are quite well-known: two pairs and are equivalent if there exists for which the following relation holds:

In the case of the elements of the form , it is less obvious how this should be done. A constructor can help us with this as it contains all the required structure for this type of general description without involving the need of focusing on the encoding.

In terms of the notations given below, in the definition of constructor, the data would specify the set of elements that are to be paired with elements in S; the data would specify the set of elements that are to be subject to relations of the form given earlier; the data and , which are used for coherence purposes, would be identities; the data and would specify the types of quotients one would like to see happening: they provide the seeds and the stems of the vertebrae given by the data coming from the preconstructor structure; the maps denoted by would map every element to (for the analytic links) and every pair where to a pair (for the quotient links); and the data j would specify how the set R injects into the localisation . With respect to the definition given below, all of these data would be associated with the canonical ring morphism .

We now give the definition of constructor. Let and be two categories and D be a small category. A constructor of type consists of a preconstructor of type , say as defined in Section 6.2, and a mapping that equips every object with a pair of sets together with:

- (1)

- two functors and called the analytic and quotient exponents;

- (2)

- two functors and called the analytic and quotient indicators;

- (3)

- a functor called the transitive analysor and, for every , a function , called the analytic link, of the following form:

- (4)