Abstract

Accurate volatility forecasting is essential for risk management in increasingly interconnected financial markets. Traditional econometric models capture volatility clustering but struggle to model nonlinear cross-market spillovers. This study proposes a Temporal Graph Attention Network (TemporalGAT) for multi-horizon volatility forecasting, integrating LSTM-based temporal encoding with graph convolutional and attention layers to jointly model volatility persistence and inter-market dependencies. Market linkages are constructed using the Diebold–Yilmaz volatility spillover index, providing an economically interpretable representation of directional shock transmission. Using daily data from major global equity indices, the model is evaluated against econometric, machine learning, and graph-based benchmarks across multiple forecast horizons. Performance is assessed using MSE, , MAFE, and MAPE, with statistical significance validated via Diebold–Mariano tests and bootstrap confidence intervals. The study further conducts a strict expanding-window robustness test, comparing fixed and dynamically re-estimated spillover graphs in a fully out-of-sample setting. Sensitivity and scenario analyses confirm robustness across hyperparameter configurations and market regimes, while results show no systematic gains from dynamic graph updating over a fixed spillover network.

Keywords:

GARCH model; graph neural network; temporal GAT; volatility cluster; optimization; LSTM; volatility spillover MSC:

91G15; 91G70; 62M10; 68T07; 05C81

1. Introduction

Volatility forecasting is essential for effective risk management, portfolio optimization, and informed decision-making in global financial markets. Volatility reflects the degree of variation in asset prices over time and acts as a fundamental indicator of financial risk and market uncertainty. A particularly challenging characteristic of volatility is its tendency to cluster, whereby periods of high volatility are typically followed by further turbulence, and periods of calm tend to persist [1]. These volatility clusters, often triggered by macroeconomic shocks, news events, or shifts in market sentiment [2], complicate the forecasting landscape and heighten the need for robust predictive models that can adapt to evolving market regimes.

Traditional econometric models such as the generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity (GARCH) family have long been employed to capture stylized features of financial returns, including volatility clustering and leptokurtosis. While these models provide valuable insights into time-varying volatility dynamics, they struggle to account for the nonlinear interdependencies and spillover effects that characterize increasingly interconnected global markets. As financial systems become more integrated, volatility in one market can rapidly propagate to others, demanding modelling frameworks that capture not only individual market behaviour but also the structural relationships that govern cross-market transmission.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) offer a powerful means of representing such interconnected systems by exploiting the graph structure underlying financial markets. Their ability to model dependencies between nodes makes them particularly suitable for volatility forecasting, where spillovers and contagion effects play a critical role. Recent studies have demonstrated the promise of GNNs for incorporating network information to enhance predictive accuracy. For example, Son et al. [3] shows that spatiotemporal GNNs combined with volatility spillover indices can improve volatility forecasts across global markets, underscoring the importance of embedding financial network structure into predictive models.

Building on these developments, this paper proposes a tailored framework for volatility forecasting: the Temporal Graph Attention Network (Temporal GAT). Our approach represents global equity markets as dynamic graphs, where nodes correspond to stock indices and edges encode time-varying interdependencies derived from either correlation networks or, more effectively, the Diebold–Yilmaz volatility spillover index. The proposed architecture adopts a temporal-first design: a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) first encodes the history of each index’s volatility proxies, after which Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN) and Graph Attention Networks (GAT) layers capture structural spillover effects and assign adaptive attention weights to influential markets. This separation of temporal and spatial learning allows the model to capture sequential volatility dynamics alongside evolving cross-market relationships more precisely.

A key contribution of this work is the demonstration that volatility spillover networks outperform traditional correlation networks in capturing the directional transmission of market shocks. Our empirical analysis shows that spillover-based graphs yield more accurate forecasts by modelling the asymmetric and dynamic nature of financial contagion. Furthermore, the Temporal GAT is evaluated using a comprehensive set of experiments over fifteen years of data from eight major global stock indices. The model is assessed across multiple forecast horizons, from short-term to monthly volatility predictions, and benchmarked against GARCH, MLP, LSTM, and alternative GNN architectures. Extensive sensitivity and scenario analyses are conducted to evaluate robustness under different hyperparameter configurations and varying market regimes. These analyses reveal that while the model produces higher prediction errors during turbulent periods—an expected outcome given increased market unpredictability—it remains stable and maintains strong relative performance compared to competing methods.

Overall, this study advances the literature by presenting a domain-specific LSTM–GCN–GAT hybrid architecture that aligns closely with the econometric structure of volatility transmission. By integrating temporal encoding with piecewise-static spillover-based graph modelling, the Temporal GAT provides a more nuanced and accurate representation of global market interdependencies. The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the literature studies in terms of volatility clustering, machine learning approaches to volatility forecasting, GNN in financial modelling and the concepts of volatility spillovers and the GNNs. Section 3 introduces the mathematical and methodological preliminaries, Section 4 presents the full methodology, Section 5 details the empirical results, including data visualization, sensitivity and scenario analyses, and the final section offers concluding remarks.

2. Related Works

Accurate forecasting of financial market volatility has been a central theme in financial econometrics; yet it remains a significant challenge due to the complex, non-linear, and interconnected nature of global markets. This section reviews the evolution of financial and volatility modelling, as well as the impact of the GNNs in such modelling.

2.1. Traditional Volatility Models and Early Machine Learning Approaches

Early efforts in volatility modelling were primarily dominated by econometric models. The concept of volatility clustering, where periods of high volatility are followed by periods of high volatility and vice versa, was first observed by [4] in 1963 and further developed by [5] with the introduction of the Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity (ARCH) model. Engle’s work demonstrated that volatility is not constant over time but can be modelled based on past behaviours, marking a significant shift in understanding financial time series. Building on this, Bollerslev [6] extended the ARCH model by proposing the GARCH model in 1986. The GARCH model improved upon its predecessor by incorporating past volatilities in addition to past shocks, allowing for more accurate forecasting of future volatility. Traditionally, models like the GARCH model have been widely used to capture volatility clustering by analyzing time-series data. While effective to some extent, these models often fail to account for the more complex, non-linear relationships among multiple assets, or even among networks of interdependent assets, in global financial markets [7]. This limitation becomes particularly evident when markets are highly interconnected, and the volatility of one market affects others through intricate spillover effects [8].

Several variations of the GARCH model have been developed to account for specific market behaviours. For instance, the Exponential GARCH (EGARCH) model introduced by [7] addresses asymmetries in financial data, particularly the tendency for adverse market shocks to increase volatility more than positive ones. Similarly, the Threshold GARCH (TGARCH) model proposed by [9] captures the idea that markets respond differently to different types of shocks. Despite their widespread adoption, GARCH models have notable limitations. They often rely heavily on historical data, which can be problematic in rapidly evolving markets. Moreover, they assume that volatility follows a single process, overlooking the complex, interconnected relationships among global financial markets [8].

These limitations prompted the exploration of alternative approaches, including machine learning (ML) techniques, which have gained prominence due to their ability to model complex, non-linear relationships. Andersen et al. [10] demonstrated the effectiveness of realized volatility in providing more accurate volatility estimates by utilizing high-frequency intraday data. Additionally, the concept of volatility spillovers, as measured by the Volatility Spillover Index, has been instrumental in understanding how volatility in one market can influence others. Neural networks, such as LSTMs, have been successfully applied to volatility forecasting, demonstrating improved capacity to capture long-term dependencies in financial data [11,12]. Hybrid models combining machine learning with GARCH have also shown effectiveness in various markets, including energy, metals, and stock markets [13]. Other ML techniques, such as Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), Support Vector Machines (SVMs), and Random Forests, have been utilized in financial forecasting. While ANNs are effective at capturing non-linear patterns, they often require extensive datasets and are prone to overfitting [14,15]. SVMs have been applied for market condition classification, and Random Forests have shown robustness, especially with large datasets. However, a common drawback of many of these models is their tendency to treat assets independently, thereby failing to capture the inherent interconnectedness of global markets.

2.2. Graph Neural Networks in Financial Modelling

To address the challenge of interconnectedness, GNNs have emerged as powerful tools for modelling complex graph-structured systems, such as financial markets. GNNs are designed to operate on graph-structured data, providing a sophisticated way to model time-series patterns and relationships among market indices by treating them as nodes within a dynamic graph. Each edge in this graph represents a relationship or correlation between indices, capturing the dynamic interdependencies between global markets. Traditional machine learning applications handle graph-structured data by applying a preprocessing step that transforms the graph’s structure into a more straightforward form, such as real-valued vectors. However, crucial information, such as the topological relationships between nodes, can be lost during preprocessing. As a result, the outcome may be unpredictably influenced by the specifics of the preprocessing algorithm [16]. Other approaches that attempt to preserve the graph-structured nature of the data prior to the processing phase have been investigated by researchers in [17,18,19]. This capability is crucial, as traditional machine learning methods often lose vital topological information when converting graph data into simpler forms.

In recent years, GNNs have gained attention, especially in financial modelling and research, due to their capacity to capture both structural and temporal dependencies evident in a financial system. This ability to account for both structural topology and temporal dynamics makes GNNs a powerful tool for tasks such as risk assessment, fraud detection, stock price prediction, and portfolio optimization in modern finance. Several comprehensive reviews on GNNs have been published. Bronstein et al. [20] offers an in-depth review of geometric deep learning, discussing key challenges, solutions, applications, and future directions, whereas [21] provides a detailed overview of graph convolutional networks. Other recent papers on GNN models are presented by researchers in [22,23,24,25].

The foundational work by [19] introduced a framework for applying neural networks to graph-structured data, laying the groundwork for iterative updates of node representation based on neighbour information. K. Xu et al. [26] provided a theoretical framework for analyzing the representational power of GNNs and their variants, whereas [3] recently demonstrated how GNNs, combined with a volatility spillover index, can improve the predictive accuracy of stock market volatility in different regions. GCNs aggregate information from neighbouring nodes, updating node features based on the graph’s topology, making them effective for semi-supervised learning. GCNs can also incorporate temporal dynamics, which is vital for fast-paced financial markets [27]. Applications of GCNs in financial modelling include predicting stock prices using correlation graphs, as demonstrated by [28], who combined a GCN with a gated recurrent unit (GRU) to capture temporal dependencies. Other recent work on GCN implementations in finance is found in [29,30,31,32,33].

Further on improving GCNs, Veličković et al. [34] developed the GATs, which integrate attention mechanisms to dynamically assign weights to neighbouring nodes, enabling the model to focus on the most relevant connections. This innovation is beneficial in multivariate time series prediction [35], financial fraud detection [36], and other financial modelling frameworks in which specific market indices exert greater influence than others. GATs utilize attention mechanisms to assign varying importance to nodes within a graph, making them practical for modelling relationships between financial entities. The model enhances the traditional methods of analyzing financial data by incorporating both the GCNs and GATs [32]. This allows the model to focus on the most relevant relationships between indices, improving the accuracy of predictions related to volatility clustering. However, traditional GATs struggle to capture temporal dependencies in data, which is crucial in the financial domain where time plays a key role.

To address this limitation, Temporal GATs have been developed to enhance GATs by incorporating temporal data. Using a temporal attention mechanism, the temporal GAT dynamically adjusts the impact of past events, allowing the model to capture not only the structure of the financial graph but also the time-dependent patterns that shape market behaviour [37,38]. This phenomenon makes temporal GATs particularly effective for financial applications, where it is crucial to account for both entity relationships and their changes over time. Unlike traditional models that consider only individual asset behaviours, the Temporal GAT model enables a deeper understanding of how assets influence one another, providing a more comprehensive analysis of market volatility. This research aims to push the boundaries of financial econometrics and machine learning by applying GNNs to better understand volatility clustering and predict it. By capturing the interconnected nature of global financial markets, this paper offers new tools for financial analysts, risk managers, and investors to improve risk assessment and make more informed decisions [39].

2.3. Volatility Spillovers and Graph-Based Models

Understanding volatility spillovers, that is, the phenomenon where volatility in one market influences volatility in another, is crucial for comprehending systemic risk and market dynamics. Diebold; Yilmaz [8,40] developed a framework to measure these spillovers using Vector Autoregressive (VAR) models. However, traditional VAR-based measures may not fully capture non-linear relationships. To overcome these limitations, recent research has increasingly turned to GNNs to model the global financial system as a dynamic graph. By representing markets as nodes and volatility relationships as edges, GNNs provide a more comprehensive understanding of volatility spillovers. A notable contribution in this area is the work of [3], who demonstrated that incorporating volatility spillover indices into a spatial-temporal GNN framework significantly improves the accuracy of volatility predictions across global markets. Their research highlighted the effectiveness of combining GNNs with spillover indices to enhance predictive accuracy for stock market volatility.

2.4. Contributions of This Research

While [3] laid the necessary groundwork by applying spatial-temporal GNNs with volatility spillovers, our research extends this knowledge through a more specialised and theoretically aligned modelling framework. In contrast to the general “spatial–temporal GNN model” examined by [3], the proposed TemporalGAT adopts a temporal-first architecture in which an LSTM encodes each market’s volatility history before any spatial aggregation occurs. This separation enables more precise and more accurate modelling of sequential volatility dynamics. Furthermore, integrating graph attention layers enables the model to learn adaptive, time-varying importance weights for neighbouring markets, capturing heterogeneity in spillover strengths that fixed diffusion-based approaches cannot represent. Finally, the study incorporates extensive sensitivity, robustness, and scenario analyses, demonstrating that the TemporalGAT remains stable across hyperparameter configurations and maintains strong relative performance under both high- and low-volatility regimes. These distinctions collectively advance the methodological precision of temporal GNN modelling for financial applications and address key limitations in prior work.

The key contributions of this paper are as follows:

- Development of a TemporalGAT for Volatility Forecasting: This paper presents a novel TemporalGAT architecture tailored for volatility prediction in global stock markets. By combining LSTM-based temporal encoding with GCN and GAT layers, the model effectively captures both sequential dependence and evolving cross-market spillovers, outperforming traditional approaches such as GARCH and MLP.

- Volatility Spillover Index as a Superior Graph Construction Method: The study demonstrates that constructing graphs using the Diebold–Yilmaz volatility spillover index significantly improves the modelling of directional shock transmission relative to conventional correlation-based methods, thereby enhancing forecasting accuracy and interpretability.

- Strict Expanding Window Robustness: Beyond the standard validation-based evaluation, the study introduces a strict expanding-window robustness check that compares fixed and dynamically re-estimated spillover graphs in a fully out-of-sample setting, showing that dynamically updating the graph structure does not yield systematic forecasting gains over a carefully constructed fixed graph, thereby strengthening the credibility and stability of the proposed modelling approach.

- Comprehensive Sensitivity and Scenario Analysis: The model is evaluated under a wide range of hyperparameter settings and market regimes, including both high- and low-volatility periods. These analyses highlight the robustness of the TemporalGAT architecture and provide practical guidance for its application across diverse financial environments.

The practical significance of this research lies in its ability to capture and model complex interdependencies between multiple indices, enhance volatility predictions, and optimize risk management techniques. Traditional models like GARCH focus on each asset’s volatility but fail to account for how volatility in one asset can spill over to other assets and vice versa. GNNs address this limitation by representing assets as nodes in a graph, with edges reflecting relationships such as correlations or mutual volatility impacts. This allows GNNs to capture interconnected market behaviour more effectively, yielding more accurate volatility-clustering models. Some of the practical benefits are seen in modelling complex asset relationships, cross-asset and multi-asset volatility spillovers, real-time systematic risk monitoring in terms of financial contagion, algorithmic trading and portfolio optimization for risk-adjusted returns, as well as handling correlation breakdowns in the face of market turmoil.

3. Preliminaries

This section introduces the fundamental concepts and methodologies essential for understanding the subsequent analysis of volatility clustering using GNNs. The topics covered include volatility proxy, the GARCH model, correlation, the volatility spillover index, and the architectures of GCNs and GATs. These concepts form the backbone of the proposed Temporal GAT model.

3.1. Volatility and Correlation Analytics

In the absence of intraday high-frequency data, we construct a daily volatility proxy based on the squared daily return. Let denote the closing price of asset i on day t. The daily log return is defined as

Following standard practice when only daily observations are available, we compute volatility using the squared daily return:

We refer to as a volatility proxy rather than realized volatility (The term “realized volatility” is typically reserved for volatility measures constructed from high-frequency intraday returns, such as the sum of squared intraday price changes (e.g., [10]), and this is considered one limitation of this study). Despite this limitation, squared daily returns remain a widely used approximation in empirical finance when intraday data are unavailable. Furthermore, because all benchmark models in our study utilize the same volatility proxy, our comparative evaluation remains consistent and informative regarding relative predictive performance under daily-frequency constraints.

3.1.1. Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity (GARCH)

The GARCH model, introduced by [6], is a widely used statistical model for estimating volatility in financial time series data. It extends the ARCH model by incorporating both past squared returns and past variances [9], allowing for a more flexible and accurate modelling of volatility clustering [8].

Let be the real-valued discrete-time stochastic process, and as the information set (field) of all information through time t, then the standard GARCH model is defined as

where (note: for , the process reduces to the ARCH(p) process and for , becomes the white noise)

and

- is the return at time t.

- and are the mean return and the error term, respectively.

- is the conditional variance (volatility) at time t.

- and are parameters to be estimated.

The GARCH model captures volatility clustering by allowing the current variance to depend on both past squared errors and past variance . Since 2013, GARCH modelling has seen significant advancements, particularly with the emergence of non-linear and hybrid approaches that enhance volatility forecasting. Recent work by [41] introduces graph-based multivariate GARCH models that capture complex dependencies in time series data. Additionally, neural network-augmented GARCH models, such as Neural GARCH [42] and deep learning-enhanced realized GARCH variants [43], have improved the ability to model dynamic, non-linear volatility patterns. Other innovations include ordinal GARCH models, which allow for a flexible structure of serial dependence [44], as well as hybrid frameworks that combine GARCH with deep learning techniques [43], which have demonstrated superior performance in capturing regime shifts and long-memory effects.

3.1.2. Volatility Spillover Index

The Volatility Spillover Index measures the extent to which volatility shocks can transfer from one market to another, reflecting the interconnectedness of the global financial market. Diebold and Yilmaz (2009, 2012) developed a framework using variance decompositions from the VAR models to quantify these spillovers [8,40]. This measure captures the transmission of volatility across financial assets or markets and provides a more dynamic and directional understanding of market interconnectedness than static correlation measures.

The calculation of the volatility spillover index typically involves a VAR model applied to a set of time series (in our case, volatility proxies of multiple market indices). The forecast error variance decomposition from the VAR model is then used to determine the contribution of shocks from market j to the forecast error variance of market i. This contribution forms the basis for the weights in our graph construction, , representing the spillover from market j to market i. The spillover index is calculated using the forecast error variance decompositions from the VAR model [40]:

where

- H is the forecast horizon.

- is the standard deviation of the error term for variable j.

- is the selection vector with one at the position and zeros elsewhere.

- is the coefficient matrix at lag h.

- ∑ is the covariance matrix of the error terms.

The total spillover index is then given by

Note: To calculate the spillover index using the information available in the variance decomposition matrix, each matrix entry is normalized by

This index provides insights into how volatility in one market influences others, which is essential for understanding systemic risk and market dynamics. The full derivation is provided in Appendix A.

3.2. Graph Theory Fundamentals

Our methodology leverages graph theory to model the interdependencies within global financial markets. A graph is formally defined as , where V is a set of nodes (or vertices), representing the individual market indices in our context and E is a set of edges (or links), representing the relationships or connections between these market indices.

Each edge indicates a relationship between node i and node j. In a weighted graph, each edge is associated with a numerical weight , quantifying the strength or nature of the relationship. In a directed graph, edges have a specific direction (e.g., ), meaning the relationship from i to j is distinct from j to i. The connectivity of a graph is represented by its adjacency matrix A, where if an edge exists from i to j, and otherwise. For weighted graphs, .

3.3. Graph-Based Deep Learning Models

3.3.1. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)

GNNs are a class of neural networks designed to operate on graph-structured data, capturing dependencies among nodes via message passing between nodes. GNNs are particularly useful for modelling relational data and have been successfully applied in various domains, including social networks, recommendation systems, and financial markets.

3.3.2. Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs)

GCNs aggregate feature information from a node’s neighbours to compute its new representation [32]. The first spatial component of the Temporal GAT architecture is a GCN layer, which captures coarse structural relationships among market indices. The GCN operates on the spillover network encoded by the Diebold–Yilmaz adjacency matrix, where edges represent the magnitude and direction of cross-market volatility transmission. The layer-wise propagation rule for a multilayer GCN is given by

where

- is the feature matrix at layer l; .

- is the adjacency matrix of the undirected graph with added self-loops, and is the identity matrix.

- .

- is the layer-specific trainable weight matrix.

- is an activation function (e.g., ReLU).

GCNs effectively capture local neighbourhood structures in graphs, making them suitable for semi-supervised learning tasks on graph-structured data. In the proposed architecture, the GCN layer takes as input the temporal embeddings generated by the LSTM and transforms them into intermediate spatial representations. This step allows the model to incorporate structural connectivity in the spillover network before applying more expressive attention-based refinements. Consequently, the GCN layer acts as a foundational spatial encoder, capturing general cross-market interactions and preparing the representations for subsequent graph attention operations.

3.3.3. Graph Attention Networks (GATs)

GATs introduce an attention mechanism to GNNs, allowing the model to assign different importance weights to different nodes in a neighbourhood. Following the GCN layers, the architecture incorporates GAT layers to learn heterogeneous spillover effects via attention-based message passing. While GCNs treat neighbouring nodes uniformly, GATs assign adaptive weights to neighbours based on their relevance, enabling the model to emphasize influential volatility transmitters. The core idea is to compute attention coefficients that indicate the importance of node features to node i [34,45].

where

- ; are the input, with N = number of nodes and F, the number of features in each node.

- is the weight matrix.

- is the attention mechanism’s weight vector.

- denotes concatenation and is the transposition.

- is the set of neighborhood of node i in the graph.

Through this mechanism, GAT layers learn to assign higher importance to nodes that exert stronger spillover effects, such as major global indices or structurally central markets. Multi-head attention further stabilizes the learning process and improves expressiveness by allowing the model to attend to different relational patterns simultaneously. In the Temporal GAT architecture, GAT layers refine the spatial embeddings produced by the preceding GCN layers, enabling the network to capture asymmetric, time-varying, and non-uniform volatility transmission. This makes the GAT component essential for modelling complex cross-market dynamics that uniform graph convolutions cannot capture.

3.3.4. Temporal Graph Attention Network (Temporal GAT)

The Temporal GAT combines the strengths of GCNs and GATs to model both the structural and temporal dynamics in graph-structured financial data [46]. This architecture is well-suited to tasks in which relationships among nodes evolve and in which capturing temporal behaviour is essential for modelling volatility clustering and spillovers. The model consists of three key components, which individually contribute to learning spatio-temporal dependencies across financial markets:

- Temporal Layers: Model the evolution of volatility proxies for each market index over time.

- GCN Layers: Aggregate structural information from neighbouring indices based on the spillover graph.

- GAT Layers: Assign adaptive attention weights to spillover linkages, emphasizing the most influential cross-market transmissions.

Temporal Layer: Explicit LSTM-Based Temporal Modelling–TemporalGAT Module (LSTM + GCN + GAT).

For each node i, we construct a rolling window of length w from the volatility proxy series. The input sequence at time t is given by

where is the one-dimensional volatility feature at time t. This sequence is processed by an LSTM network with hidden size :

and we take the final hidden state as the temporal representation of node i at time t. Collecting all nodes, we form the matrix , which serves as input to the graph module.

The spatial block consists of two GCN layers followed by two GAT layers, applied on the spillover (or correlation) network. Let denote the normalized adjacency matrix and the trainable weight matrices of the GCN layers. We compute

where is a nonlinear activation function.

Next, we apply graph attention to the GCN features . For nodes i and j, the attention coefficient is given by Equation (9). The attention-weighted node representation is given by

and a second GAT layer is then applied analogously to refine the node embeddings further, yielding .

Finally, the output of the graph block is passed through fully connected layers to produce either a single-horizon forecast (e.g., ) or a vector of multi-horizon forecasts. For node i, the prediction is

where denotes a small multilayer perceptron. In our main multi-horizon experiments, we set

corresponding to -day ahead volatility forecasts. This architecture makes the temporal component explicit via the LSTM, while the subsequent GCN + GAT stack captures the cross-sectional spillover structure encoded in the Diebold–Yilmaz or correlation-based graphs. Thus, it can be summarized as

3.4. Rationale for the Combined GCN–GAT Architecture and Its Distinction from Existing Temporal GNNs

The combined use of GCN and GAT layers in our TemporalGAT architecture is a deliberate design choice that leverages the complementary strengths of the two operators. GCN layers provide a stable mechanism for aggregating information over the graph’s topology, making them well-suited for capturing the broad, relatively persistent structure of cross-market connectivity. By diffusing information from both direct and indirect neighbours, GCNs establish a strong baseline representation of how volatility propagates through the market network.

GAT layers, in turn, introduce an adaptive mechanism that assigns learnable attention weights to neighbouring nodes. This allows the model to focus on the most influential spillover channels at each point in time, an essential capability in financial markets, where interdependencies can shift abruptly in response to macroeconomic announcements, geopolitical events, or regime changes. The sequential use of GCN followed by GAT thus enables the model to capture long-term structural dependencies while dynamically reweighting short-term shocks, producing richer and more context-sensitive volatility forecasts.

Our architecture differs from existing temporal GNNs and “Temporal-GAT” variants in the machine-learning literature. For example, [3] builds two rolling financial networks, a Diebold–Yilmaz spillover network and a correlation network and feeds these into a diffusion convolutional recurrent neural network (DCRNN), where diffusion convolution models spatial dependence and a GRU implicitly handles temporal dynamics. Their model uses only realized volatility as an input and produces single-horizon forecasts. In contrast, our framework constructs multiple piecewise-static graph forms and explicitly separates temporal and spatial learning: each node’s volatility history is encoded by an LSTM, after which the resulting embeddings propagate through stacked GCN → GAT layers. This separation allows the model to learn directional, weighted, and time-varying interdependencies with adaptive attention, rather than relying on a single recurrent mechanism to capture both temporal and spatial structure.

Furthermore, whereas standard temporal GNNs often apply attention directly across time or operate on event-driven dynamic graphs, our approach cleanly decouples the two dimensions. Temporal persistence is modelled exclusively through a node-level LSTM applied to rolling windows of volatility proxies or GARCH volatility proxies. At the same time, spatial dependencies are captured through GCN/GAT layers operating on econometrically constructed spillover or correlation networks, rather than on learned or time-stamped interaction graphs. The GAT component is used strictly in its spatial-attention form [34], rather than as a temporal attention mechanism. Finally, the architecture is tailored to financial forecasting by supporting multi-horizon prediction and enabling formal econometric evaluation through Diebold–Mariano tests and bootstrap confidence intervals. Thus, the proposed model is not intended as a universal temporal-GNN architecture but rather as a domain-specific LSTM–GCN–GAT hybrid designed to capture volatility persistence and cross-market spillovers in an interpretable and empirically grounded manner (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of Our TemporalGAT With Existing Temporal GNN Architectures.

4. Methodology

This section outlines the comprehensive methodology adopted to explore and analyze volatility clustering in global stock markets using a Temporal GAT approach. The research aims to advance the understanding and forecasting of volatility by leveraging the financial markets’ dynamic and interconnected nature. A systematic, step-by-step approach is presented, clarifying the strategies, techniques, and tools employed throughout the study, ensuring transparency and replicability of the findings.

4.1. Problem Formulation

Given a dynamic financial system represented as a time-evolving graph sequence , where each node corresponds to a global stock market index and each edge captures the directional relationship between indices i and j at time t (e.g., through correlation or volatility spillover), the objective is to predict the volatility proxies computed from daily returns of each index at a future time step using historical information up to time t.

Formally, the learning task is to estimate a function:

where

- is the predicted volatility proxies of index i at time .

- is the historical sequence of node features for index i over a look-back window of size w.

- is the sequence of regime-dependent graph snapshots representing market structure from time to t.

- denotes the model parameters to be learned.

- d is the dimensionality of node features (e.g., volatility proxies, closing price, or trading volume).

The task is modelled as a temporal graph-based regression problem. The proposed Temporal GAT is designed to capture temporal dependencies (i.e., past patterns and trends in volatility for each market index) and structural dependencies (i.e., dynamic interrelationships among market indices over time). For this study, we consider the look-back window (denoting the number of past trading days used as input), the forecast horizon (corresponding to short-term (1-day) to long-term (1-month) predictions), the node features which includes primarily volatility proxies, with comparative experiments using closing prices and trading volumes. The piecewise-static graphs are constructed using either the Pearson correlation coefficient or the Volatility Spillover Index derived from a VAR model.

4.2. Graph Construction

The core of our methodology lies in representing the stock market as a directed graph, where the indices are nodes and the relationships between them form directed edges. In a directed graph, each edge has a direction, indicating the flow of influence or information from one node (market index) to another. This structure is particularly suitable for capturing asymmetric relationships often observed in financial markets, in which one market can significantly impact another without necessarily experiencing a reciprocal effect [40]. We employed two primary methods for constructing these directed graphs: the Correlation Method and the Volatility Spillover Index Method.

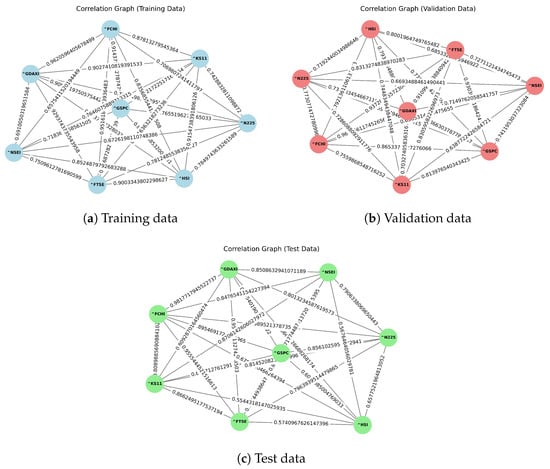

Correlation Method: In this method, Pearson correlation coefficients between the volatility proxies of the indices during the training period were calculated. These coefficients form the graph’s edges, yielding a symmetric adjacency matrix with self-loops on the diagonal (each entry is 1). The Net Correlation Index (NCI) for each market was calculated as the sum of its correlations with other markets [See Figure 1]. This method helps identify the strength of the correlation between different indices, providing a clear view of the interconnectedness of these markets [48,49].

Figure 1.

Visualization of graphs by the correlation method.

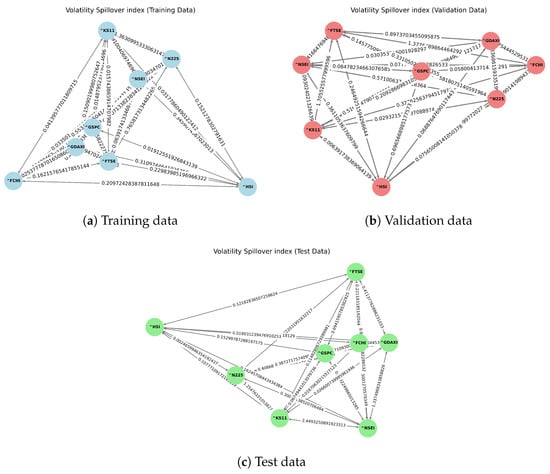

Volatility Spillover Index Method: Based on the framework by [8,40], this method measures the degree of volatility transmission between indices using variance decomposition from a VAR model. We employed a lag order of 4 () and a 5-step ahead forecast horizon () to derive these indices [See Figure 2]. The resulting spillover index matrices illustrate the directional influence one market exerts over another, capturing the dynamic nature of volatility transmission in the financial markets.

Figure 2.

Visualization of graphs by the volatility spillover method.

Figure 1 and Figure 2 represent a graph where each node is a global stock market index (e.g., HSI, FTSE), and the directed edges show relationships between them. The numbers on the edges indicate the strength of the connection between two indices, which can be measured using correlation or the volatility spillover index method. For instance, HSI has a connection strength of 0.229 (spillover method) to FTSE in the training data. The comparison between training, testing, and validation data reflects how these relationships change over time, with the numbers indicating varying connection strengths.

Consider the training dataset in Figure 1, when stock indices are highly correlated, as seen between indices like GSPC vs. FCHI, HSI, KS11 (correlations of 0.91, 0.87, 0.90 respectively), KS11 vs. FTSE, HSI, GSPC, GDAXI (correlations of 0.91, 0.92, 0.90, 0.90 respectively), FTSE vs. GDAXI, HSI (correlations of 0.92, 0.90 respectively) and GDAXI vs. FCHI (correlation of 0.96), it suggests that these markets are likely to experience volatility clustering together. If one market (e.g., GSPC) enters a period of high volatility due to market turbulence or tensions in the USA, this volatility can affect the French market (CAC 40) because the two markets are highly correlated. In addition, moderate-to-low correlations (e.g., between NSEI vs. FCHI, and N225 and GDAXI, with correlations of 0.66, 0.67, and 0.69, respectively) indicate that while there is some shared volatility, these indices do not always cluster together. Thus, these cluster effects reflect interconnectedness because regions with strong trade links, similar industry exposures, or shared investor bases tend to exhibit co-movement in volatility. This is especially true for global markets such as the US and Europe, as well as for regional clusters such as Europe and Asia.

4.3. Graph Construction via Volatility Spillovers

To capture cross-market dependence in volatility dynamics, we construct directed graphs based on volatility spillover effects using the Diebold–Yilmaz framework. Specifically, volatility proxies for all indices are modelled jointly using a Vector Autoregression (VAR), and generalized forecast error variance decompositions (GFEVD) are employed to quantify the proportion of forecast uncertainty transmitted from one market to another.

Let denote the vector of volatility proxies across N equity indices. For a given data partition, a VAR model is estimated on , and the resulting GFEVD yields a spillover matrix , where the -th entry measures the contribution of shocks in market j to the forecast error variance of market i. This matrix is interpreted as a weighted, directed adjacency matrix, with nodes representing indices and edge weights capturing the magnitude of volatility transmission.

To ensure a strict separation of information sets, the spillover networks are constructed in a piecewise-static, regime-dependent manner. Separate adjacency matrices are estimated for the training, validation, and test periods, using only the volatility proxies data contained within each respective partition. Within each period, the resulting graph topology is held fixed and represents the average spillover structure of that regime. This design prevents information leakage across evaluation phases while providing a stable and statistically robust representation of cross-market volatility linkages.

We emphasize that the resulting graphs are not updated at every forecasting origin within a period. While rolling-window or fully time-varying spillover networks are conceptually appealing, such approaches can be statistically unstable in small systems (eight stock indices) and short samples, particularly when VAR-based variance decompositions are employed. Accordingly, the adopted piecewise-static construction offers a principled trade-off between econometric reliability and temporal segmentation. Extending the framework to fully dynamic spillover networks is left for future research.

Remark 1 (On Graph Construction and Look-Ahead Bias).

The spillover-based adjacency matrices are constructed separately for the training, validation, and test sets, using only information available within each respective period. As a result, no future observations beyond the boundaries of a given partition are used when defining the graph topology for that period. While the graph remains fixed within each regime, this piecewise-static design avoids look-ahead bias across evaluation phases and preserves a strictly out-of-sample forecasting setup. A fully rolling or expanding-window graph construction, although feasible, is beyond the scope of this study and left for future work.

4.4. Node Features

The target variable of interest is the daily volatility proxies for each index i. In the baseline specification, the volatility proxy is also used as the primary node feature. Specifically, for each node i and time t, we construct a look-back window of length w,

which serves as the input feature vector for node i in the spillover graph at time t. The TemporalGAT therefore learns a mapping from past volatility proxy and contemporaneous network structure to future volatility proxy.

4.5. Model Architecture Overview

The proposed Temporal GAT integrates temporal sequence modelling with graph-based spatial learning, enabling joint extraction of time-series patterns and cross-market spillover effects. The architecture is designed to forecast volatility proxy across multiple international equity indices by leveraging both historical dynamics and contemporaneous interconnections encoded in the Diebold–Yilmaz spillover network. At a high level, the architecture processes information through four sequential modules:

- 1.

- Temporal Module (LSTM): Each market index is represented by a rolling look-back window of volatility proxies. An LSTM network transforms this sequence into a temporal embedding that captures persistence, structural breaks, and nonlinear dynamics in volatility.

- 2.

- GCN Layers: Two GCN layers first aggregate neighbourhood information based on the adjacency structure, producing a shared spatial embedding for each node. The first GCN layer transforms the node features from their initial dimension to a hidden dimension. This transformation is tested with hidden dimensions of 32, 64, and 128 in our implementation to determine the optimal size. The second GCN layer further processes these transformed features by applying a ReLU activation function to introduce nonlinearity, which is crucial for capturing complex patterns.

- 3.

- GAT Layers: The output is passed to two GAT layers, which adaptively learn the influence weights across markets through attention coefficients. This enables the model to differentiate between strong and weak spillover relationships. These layers focus on significant nodes, prioritizing crucial information within the graph. The attention mechanism in each GAT layer is configured with multiple heads (specifically 4 or 8 heads in our tests), allowing the model to learn different aspects of the data from multiple representation subspaces simultaneously. This setup enhances the model’s ability to capture diverse relational patterns among data points [50].

- 4.

- Multi-Horizon Output Head: A series of three fully connected layers maps the spatio-temporal embeddings to volatility forecasts across multiple future horizons. They incorporate a ReLU activation function, and each applies nonlinear transformations to capture higher-order interactions. The final output layer produces a scalar one-step-ahead volatility forecast for each index. These layers are crucial in synthesizing the learned graph-based features into a comprehensive form suitable for the final prediction task [19].

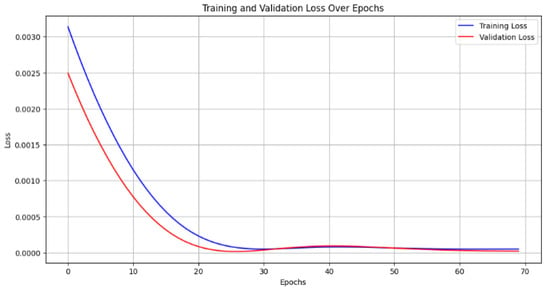

- 5.

- Training and Optimisation: The model is trained end-to-end using the Adam optimiser and the mean squared error (MSE) loss function. The entire architecture—temporal feature extraction, spatial propagation, and prediction—is updated jointly to minimize forecasting error. A grid search strategy is utilized to fine-tune the model’s hyperparameters, including the number of hidden dimensions, attention heads, and the learning rate. The learning rate values tested are 0.0001, 0.001, and 0.01. This optimization involves training the model across a predefined grid of parameter combinations and monitoring performance through the Mean Squared Error (MSE) on a validation set. The goal is to minimize MSE across 70 training epochs, refining the model’s ability to forecast market volatility accurately.

The overall pseudocode is provided in Algorithm 1. Thus, the combination of temporal sequence learning and graph-based relational modelling allows the architecture to capture both volatility clustering in individual markets and contagion effects across the global financial network.

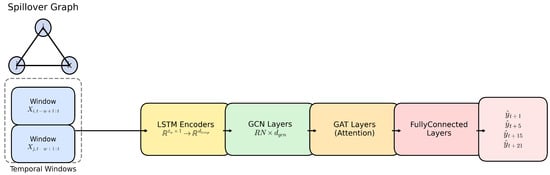

Figure 3 illustrates the complete processing pipeline. The model first extracts temporal features through an LSTM, then applies graph convolutions and attention mechanisms to capture spatial spillovers, and finally outputs a vector of predicted volatilities for horizons .

| Algorithm 1 Pseudocode for the Temporal GAT Multi-Horizon Forecasting Framework |

Initialize model parameters, tickers, date range, rolling window w, and forecasting horizons .

|

Figure 3.

General design for the Temporal GAT model.

4.6. Other Models for Comparison

To evaluate the performance of the Temporal GAT model (TGATM), we compared it against six alternative models, each utilizing different methodologies:

- Baseline Model(BM): The BM is crafted to process the volatility proxies for transforming and capturing the volatility spillover index of financial markets without integrating graph-based complexities. This model is included to isolate the contribution of graph structure and temporal modelling. The model receives each index’s feature vector independently and performs forecasting without any spatial or temporal interaction between nodes. The architecture consists of three fully connected hidden layers with ReLU activations and dropout regularization, followed by a final linear layer that outputs the 15-day-ahead volatility forecast. Since the MLP processes each index in isolation and lacks access to spillover relationships or historical sequences, it serves as a minimal, non-graph and non-temporal benchmark for evaluating the value added by both the spatial message-passing components and the temporal encoders used in the TemporalGAT and GARCH-TGAT models. The architecture comprises three hidden layers, each with dimensions configurable to be either 32, 64, or 128, allowing the model to adapt its complexity to the richness of the input data.

- Static GNN-GATM (SGNN-GATM): As a non-temporal benchmark, we implement an SGNN-GATM that uses only cross-sectional spillover structure and ignores all time-series dynamics. Each index is represented by a node whose feature is the most recent observed volatility value, and information is propagated solely across the static spillover graph. The model consists of a single GCN layer followed by a single GAT layer, enabling capture of first- and second-order spatial dependencies but no temporal evolution. A fully connected output layer then maps the learned node embeddings to a one-step-ahead volatility prediction. Because this model does not use historical windows, recurrent units, or temporal attention mechanisms, it serves as a minimal spatial baseline. All hyperparameters (hidden dimensions and attention heads) are kept consistent with those used in TGATM for fair comparison.

- Deeper GNN-GATM (DGNN-GATM): To ensure that the weaker performance of the simple static GNN is not merely due to under-capacity, we additionally construct a DGNN-GATM baseline. This model extends the shallow spatial architecture by stacking multiple graph convolutional layers (), allowing the network to aggregate spillover information from higher-order neighbourhoods without incorporating any temporal structure. Node features consist solely of the most recent observed volatility value, with no historical window or recurrent component. After spatial message passing, two fully connected layers refine the node embeddings before a final linear layer produces the 15-day-ahead forecast. All hyperparameters (hidden dimensions and attention heads) are kept consistent with those used in TGATM for fair comparison.

- GARCH Temporal GAT Model (GARCH-TGATM): The GARCH-TGATM incorporates the GARCH methodology for transforming raw data into a format suitable for graph-based analysis, enhancing the traditional volatility modelling approach. This model leverages the strengths of both GCNs and GATs to effectively model the dynamic relationships within financial markets. To integrate econometric volatility structure into the graph-based forecasting framework, we construct a GARCH-TGAT model in which node features are derived from GARCH(1,1) conditional volatility estimates.For each index i, a GARCH(1,1) model is fitted to daily log-returns, yielding the conditional volatility series . The TGAT node feature vector is formed by taking the most recent W values , which encode the nonlinear persistence, clustering, and mean-reversion properties captured by the GARCH process. These GARCH-based temporal windows are fed into the TGAT architecture, which consists of an LSTM temporal encoder followed by stacked GCN and GAT layers that learn the cross-market spillover structure. Thus, unlike TGAT variants operating on raw price-based volatility measures, the GARCH-TGAT explicitly embeds traditional econometric volatility dynamics within a temporal-spatial neural representation.

- Correlation Temporal GAT Model (C-TGATM): The Correlation-TGAT model uses a correlation-based graph structure to capture static interdependencies between global equity indices. Instead of estimating directional spillovers, the model constructs an undirected graph where edges represent statistically significant return–volatility correlations computed from a rolling window of historical data. This graph encodes the strength of co-movement between markets, allowing TGAT to propagate temporal features across highly correlated nodes. Each node is assigned a temporal sequence of volatility proxies (or GARCH-based volatility proxies), which is then processed through the Temporal-GAT architecture combining LSTM-based temporal encoding and GAT-based spatial attention. The resulting framework provides a benchmark that isolates pure correlation-driven connectivity, enabling comparison with the Spillover-TGAT model, which uses structural VAR-based spillover linkages.

- Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM): To isolate the contribution of temporal dynamics from the graph-learning component, we include a pure LSTM network as a non-graph baseline. The LSTM operates solely on the historical volatility sequence of each index, without incorporating any cross-market relational structure. For each node, the model receives a sliding window of past volatility proxies and predicts the 15-day-ahead volatility target. This baseline is intentionally structured to match the temporal depth of the TGAT model, ensuring a fair comparison focused exclusively on temporal modelling capacity. Because LSTMs are well known for their ability to capture long-range dependencies and nonlinear dynamics in time-series data, this experiment helps determine whether the performance improvements observed in TGAT stem from the graph-based message passing or simply from the temporal modelling framework.

5. Empirical Results and Discussion

This section presents the data visualization, model analysis, sensitivity studies, and robustness tests.

5.1. Data Visualization and Analysis

The data used in this study focuses on eight major global market indices: GSPC—S&P 500 (USA), GDAXI—DAX (Germany), FCHI—CAC 40 (France), FTSE—FTSE 100 (UK), NSEI—Nifty 50 (India), N225—Nikkei 225 (Japan), KS11—KOSPI (South Korea) and HSI—Hang Seng Index (Hong Kong). These indices were selected due to their significant influence on global financial markets [3]. The dataset was sourced from Yahoo Finance and spans November 2007 to June 2022. The volatility proxy (VP) data were computed using daily adjusted closing prices, following the approach suggested by Andersen et al. [51]. The dataset was divided into three subsets: a training set (1891 datasets spanning from November 2007 to August 2014), a validation set (756 datasets from September 2014 to December 2017), and a test set (1136 datasets from January 2018 to June 2022). These subsets, respectively, cover 50 20 and 30% of the total data, ensuring a robust evaluation of the model’s performance across different time periods [3].

Descriptive statistics (Table 2) of the volatility proxy data were computed to gain insights into the underlying distribution and characteristics of the market indices. The mean volatility ranged from 0.046 to 0.059, reflecting the average level across the indices. The standard deviation, varying between 0.028 and 0.034, indicated the extent of dispersion in the volatility data. Skewness and kurtosis metrics highlighted the non-normality of the volatility distributions, with positive skewness values ranging from 2.28 to 3.23 and kurtosis values ranging from 10.47 to 20.04, suggesting heavy tails. The Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test results confirmed the stationarity of the data across all indices, with p-values significantly below 0.05. These statistics ensure that the time series data is stable and suitable for GNN modelling without further transformations [52].

Table 2.

Statistical properties of selected indices.

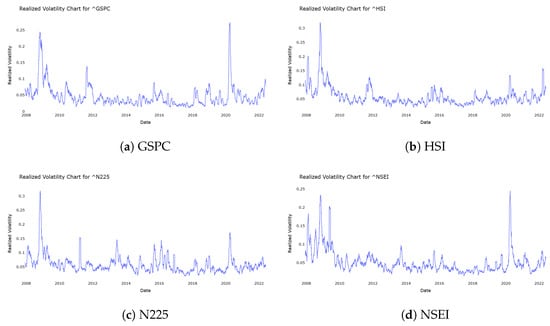

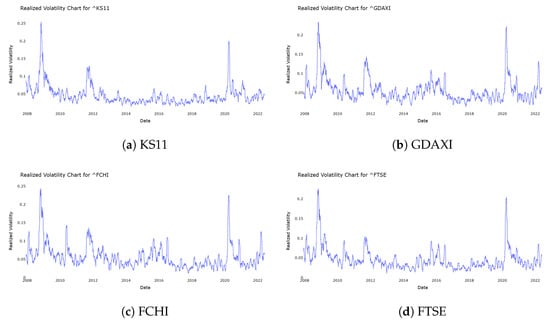

To provide a visual representation of the volatility proxy data across the eight global market indices, a time-series plot was generated that captures the daily adjusted closing prices. Figure 4 and Figure 5 present the volatility proxy data for the eight selected indices, highlighting periods of high and low volatility. The graph illustrates the volatility proxy data over the training, validation, and test periods, enabling a better understanding of market behaviour during major global events, such as the 2008 financial crisis, Brexit, and the COVID-19 pandemic, all of which contributed to significant market volatility. The analysis of volatility proxy data reveals significant clustering behaviour across global market indices, particularly during major financial events.

Figure 4.

Volatility proxy data for selected indices (Part I).

Figure 5.

Volatility proxy data for selected indices (Part II).

Furthermore, to evaluate and compare the models’ forecasting performance, several commonly used error metrics are calculated. These metrics quantify forecast accuracy by measuring deviations between observed and predicted values. Below are some of the assessment metrics employed in this study.

Let represent the actual observed value at time t, and the corresponding forecasted value and n, the sample size. Then,

- Mean Absolute Forecast Error (MAFE):

- Mean Squared Error (MSE):

- Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE):

- R-squared:

5.2. Comparative Analysis with Traditional Econometric Models

The empirical results in Table 3 show that the TGATM consistently outperforms the classical econometric benchmarks — GARCH(1,1), EGARCH(1,1), and HAR-RV, across both evaluation metrics. Temporal GAT achieves the lowest average MSE (0.01165), indicating superior robustness to large forecast deviations and volatility shocks. Its ability to minimize significant errors suggests that the model effectively captures nonlinear dependencies, cross-asset spillovers, and regime-switching patterns that traditional parametric models are unable to represent. Furthermore, Temporal GAT achieves the smallest average MAFE (), substantially lower than that of the econometric alternatives. This highlights its exceptional precision in predicting daily volatility levels across all indices, providing forecasts that more closely align with observed market dynamics.

Table 3.

Out-of-sample error values (TGATM vs. Econometric models).

The econometric models perform relatively worse because they rely on rigid parametric structures that impose smooth and gradual volatility adjustments, causing them to lag during periods of rapid volatility shifts. Although EGARCH offers modest improvements by modeling asymmetry, its performance remains constrained by static functional forms. In contrast, the Temporal GAT architecture leverages graph attention mechanisms and deep temporal representations, enabling it to learn complex, nonlinear relationships in the data and adapt effectively to abrupt market changes. The combined superiority of TGAT in both MSE and MAFE underscores its advantage in capturing real-world volatility behaviour, suggesting that graph-based deep learning approaches provide a more accurate and resilient framework for financial volatility forecasting than traditional econometric methods.

5.3. Comparative Analysis with ML-Related Models

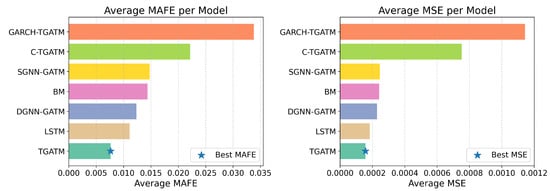

This section compares the out-of-sample error values for the following models: BM, LSTM, SGNN-GATM, DGNN-GATM, TGATM, GARCH-TGATM, C-TGATM. The forecasting results presented in Table 4 compare the predictive performance of several neural and econometric architectures across eight major global equity indices (window size of 15 days).

Table 4.

Out-of-sample error values for forecast window value of 15.

The TGATM consistently achieves the lowest or near-lowest MAFE and MSE values for most markets, particularly for indices with strong temporal dependencies such as the S&P 500 (GSPC), DAX (GDAXI), and Hang Seng Index (HSI). This demonstrates the model’s ability to capture dynamic cross-market interactions effectively. In contrast, the GARCH-augmented variant of TGAT model performs notably worse, with substantially higher errors across all indices. These findings suggest that integrating GARCH-type volatility priors may introduce noise that disrupts the temporal attention mechanism rather than complementing it. Meanwhile, models such as the DGNN-GATM and LSTM perform competitively, especially on relatively stable markets like N225 and KS11, highlighting that purely temporal or purely structural learning can be effective when market regimes are less volatile.

The C-TGAT model performs well on some indices (e.g., KS11) but, overall, exhibits larger errors than the TGATM, indicating that static correlation structures alone are insufficient to capture the nonlinear, time-varying dependencies inherent in global financial markets. Traditional baseline approaches, including the BM and SGNN models, show consistently higher error magnitudes, reinforcing the importance of temporal attention and piecewise-static graph modelling in financial forecasting. Collectively, these results highlight the superiority of the TGAT family, especially the standard TGATM, over static or correlation-based architectures. The performance differences across indices also underscore the varying degrees of temporal complexity and interconnectedness among global markets, demonstrating the necessity of models capable of capturing both sequential patterns and evolving inter-market relationships.

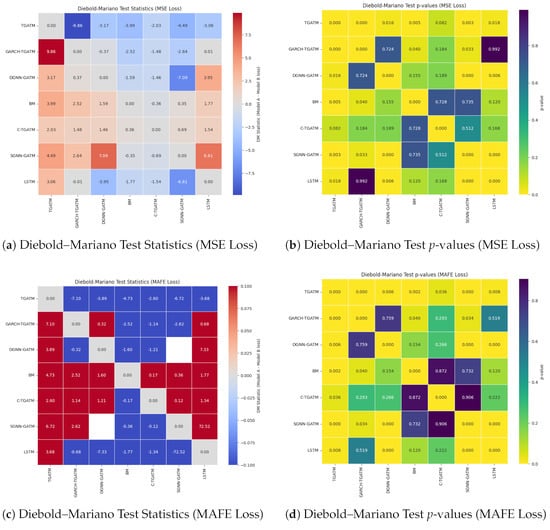

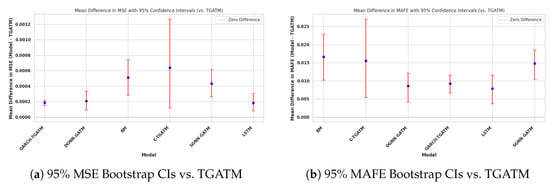

Furthermore, based on the average errors (See Figure 6), TGATM achieves the lowest MAFE and MSE, confirming it as the most accurate and stable model across all indices. LSTM and DGNN-GATM also show strong performance, indicating that temporal and graph-based structures can generalize well but still fall short of TGATM’s efficiency. In contrast, GARCH-TGATM records the highest average errors, suggesting that incorporating GARCH-based volatility components negatively impacts forecasting accuracy.

Figure 6.

Model-wise comparison of average prediction errors.

Remark 2.

When constructing a financial forecast model, it is essential to balance the trade-off between forecast window size and the model’s predictive performance. For tasks that require short-term accuracy, such as day trading, a shorter forecast window can improve performance by focusing on near-term patterns and increasing reliability. On the other hand, medium- to long-term forecasting requires a larger forecast window size to capture broader trends. In the case of the TGATM, reducing the window size tends to improve short-term forecasts, but an optimal window size is needed, as a smaller window can lead to model overfitting, thereby degrading performance.

5.4. Model Analysis

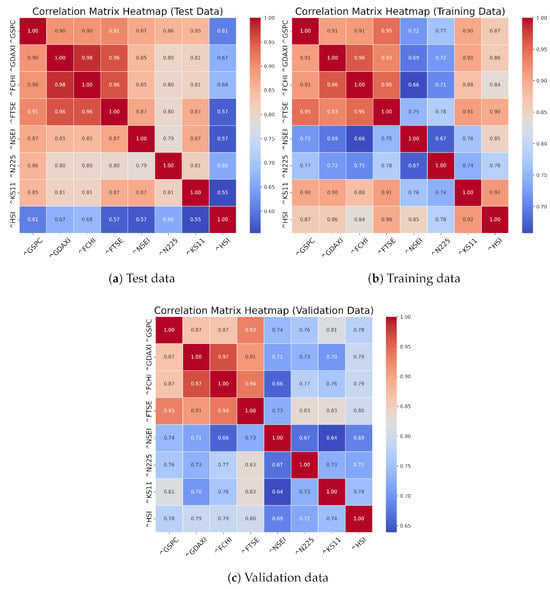

In this section, we analyze the distinctions between the correlation matrix and volatility spillover index heatmaps as tools for assessing relationships among market indices. Both methodologies provide valuable insights into the interconnectedness of financial markets, but they do so through different avenues. The correlation matrix provides a snapshot of linear relationships, while the volatility spillover index heatmap offers a dynamic view of how volatility transmits between indices over time. Utilizing both tools together can provide a more comprehensive understanding of market interactions and risk dynamics.

In Figure 7, we display the correlation matrix heatmaps for the training, validation and testing datasets. The figures show high interdependence across all US and European Markets datasets, with consistently strong correlations (above 0.90) between the S&P 500 and major European indices like FTSE, GDAXI, and FCHI. These relationships indicate that Western markets move closely together, likely due to similar economic factors. For the Asian markets, the HSI shows the most independence, with lower correlations in the test data, especially with the US market. Japan (N225) shows moderate correlations, while South Korea (KS11) is more aligned with global markets. India (NSEI) shows increasing integration over time, with its correlations rising in the test data. Finally, regarding changes across datasets, we observed that training data exhibits the most robust correlations, particularly between the US, European, and South Korean markets. The validation data presents slightly lower correlations but maintains the same general trends. In contrast, the test data shows more variability, especially with HSI (Hong Kong) becoming more independent and NSEI (India) increasing its correlations with global indices.

Figure 7.

Correlation index heatmaps of train, validation and test.

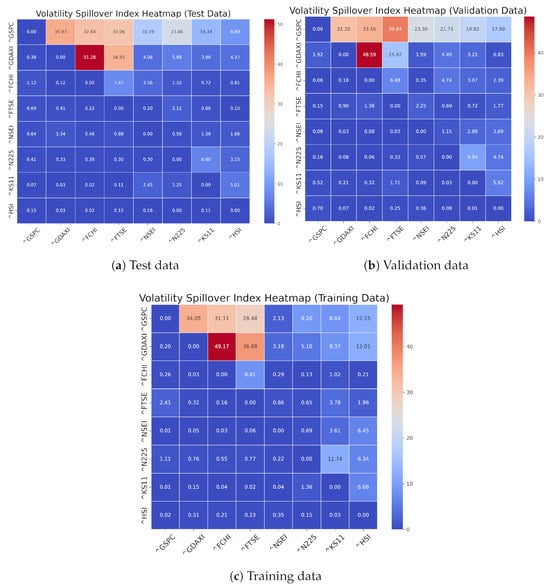

In contrast, the volatility spillover index focuses specifically on the transmission of volatility between indices. Using the Diebold–Yilmaz methodology, this approach captures how shocks to one index affect the volatility of others over time. The spillover index matrix provides a directional measure of volatility transfer, illustrating which indices are net transmitters or receivers of volatility. This is particularly useful during periods of market stress, as it identifies the channels through which volatility propagates, offering a deeper understanding of market dynamics beyond mere correlation.

In Figure 8, we observe the strongest spillover (49.17) in the training dataset, which indicates that fluctuations in GDAXI significantly influence FCHI’s volatility. This relationship remains robust in both the training and test datasets (51.28), suggesting a consistent dynamic between these indices. There is also a spillover value of 34.05 in the training dataset, suggesting a significant relationship, and these indicate that movements in the S&P 500 can affect the volatility of GDAXI. Also, the spillover value remains high at 35.97 in the test dataset, further confirming the interconnectedness between these indices. The diagram also indicates some changes in the spillover graphs, especially between FCHI and GSPC. We observed that the spillover from the training data (18.19) to the test data (14.34) decreased, suggesting that the influence of French market volatility on US markets may be weaker. This phenomenon could result from varying market conditions or economic factors that affect regions differently over time. Finally, the spillover between the HSI and the NSEI is low. These indices often exhibit spillover values close to zero, indicating that fluctuations in the other markets studied have less influence on them. For example, NSEI has several spillover values of 0.00, highlighting its independence.

Figure 8.

Volatility Spillover index heatmaps of train, validation and test.

Thus, the Temporal GAT model, when applied to volatility spillover indices, exhibits superior performance compared to models based solely on correlation analysis. The model identifies not just the relationships between indices but also how volatility evolves and impacts markets over time, leading to a more robust prediction and analysis framework. This makes the Temporal GAT model a valuable tool for understanding the complexities of financial markets, especially in periods of heightened volatility.

5.5. Sensitivity Analysis

The sensitivity analysis in this section focuses on evaluating the Temporal GAT model’s response to varying configurations and input parameters. The aim is to assess how changes in the temporal aspects and node features impact the model’s performance. We investigate three specific configurations, starting with variations in time window size to capture different levels of temporal dependencies, then evaluating the impact of different node features and concluding with analyzing the influence of hyperparameter tuning. Each of these aspects is explored in the subsections below.

5.5.1. Temporal Aspects (Time Window Size)

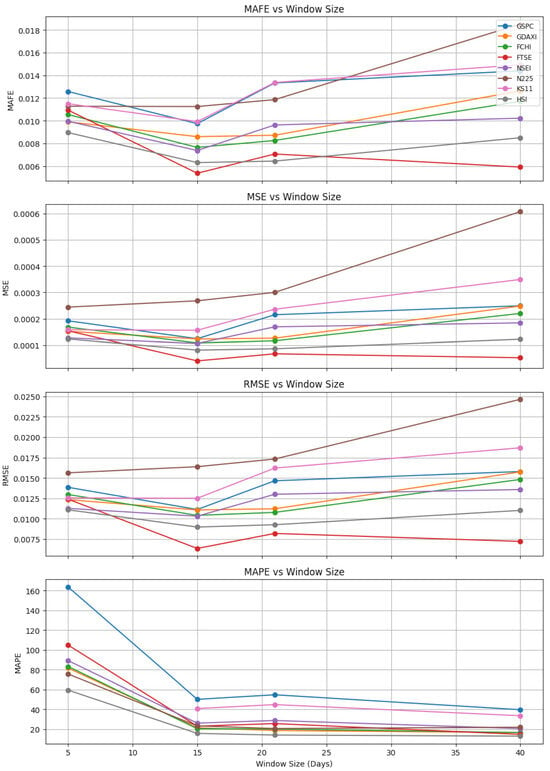

The time window size is a critical parameter that determines the extent of historical data used for volatility prediction. The Temporal GAT model is exposed to different temporal patterns by varying the time window size, thereby capturing short- or long-term dependencies in financial time series data. In this analysis, we analyze the trend using four time window sizes (Note: Window size of 21 represents approximately one trading month.), 5, 15, 21, and 40 days, to investigate their effect on the prediction accuracy and model stability. Table 5 summarizes the comparative performance of different time window sizes for each metric—MAFE, MSE, RMSE, and MAPE across the eight market indices. This comparison highlights the Temporal GAT model’s sensitivity to temporal aspects and guides the selection of an optimal window size across different forecasting scenarios.

Table 5.

MAFE, MSE, RMSE and MAPE values for Different Window Sizes.

From Table 5 and Figure 9, we observe that across most indices, the error metrics (MAFE, MSE, RMSE) generally increase with window size. When window sizes are smaller, such as 15, FTSE performs well across a wide range of error metrics, suggesting that it is simpler to forecast with high accuracy. Across all metrics and window sizes, N225 typically exhibits higher errors, especially at larger window sizes (e.g., window size 40), making accurate forecasting more difficult. In particular, MAPE shows a wide range of errors in GSPC, indicating that its percentage forecast error varies considerably across window sizes.

Figure 9.

MAFE, MSE, RMSE and MAPE values for Different Window Sizes.

Furthermore, regarding the MAFE, we observe that the GSPC and GDAXI exhibit increasing errors as the window size increases, whereas the FTSE has the lowest MAFE values, particularly for smaller window sizes. For the MSE, the errors generally increase with larger window sizes across all indices, though some, like FTSE, maintain relatively low values throughout. For the RMSE, the errors grow with window size, with N225 consistently showing higher RMSE than other indices. Finally, the GSPC and KS11 demonstrate the highest variation in percentage error, while HSI and GDAXI tend to have more stable MAPE values across different window sizes when considering MAPE. Hence, this indicates that smaller window sizes generally lead to more accurate forecasts, whereas larger window sizes result in increased error and reduced model precision.

5.5.2. Graph Properties (Node Features)

In this section, we explore the Temporal GAT model’s sensitivity to variations in node features. Within the proposed framework, each stock index is represented as a node whose features are constructed from different market-based time-series inputs, enabling the model to capture both temporal dynamics and cross-market spillover effects. Four node feature configurations are evaluated: volatility proxies, closing price, trading volume, and a combined price-and-volume specification, to assess how distinct sources of market information contribute to forecasting volatility proxies. Models using volatility proxies or closing prices as node features achieve comparatively strong predictive accuracy, reflecting the fact that both past volatility and price levels carry information relevant to future volatility dynamics.

In contrast, trading volume used in isolation yields substantially poorer results, consistent with its well-documented noisiness, regime dependence, and relatively weak short-run relationship with future volatility when not conditioned on price movements [53]. Volume has unstable and limited predictive power for future return volatility once information in prices and returns is taken into account. In most cases, its apparent explanatory power disappears entirely when proper return-based volatility dynamics are modelled [53]. Thus, feeding the GNN with volume alone deprives the model of the more direct signals about price variability and return magnitudes that are critical for short-horizon volatility forecasting, leading to much weaker performance than feature sets that include volatility proxies or closing prices.

To provide a richer representation, the combined specification assigns each node a two-dimensional feature vector that integrates the closing price and trading volume. This design allows the GNN to learn interactions between price dynamics and liquidity conditions and to evaluate whether volume adds incremental predictive value once contextualized by price behaviour, offering a more comprehensive view of how different market features jointly shape volatility outcomes.

The empirical results presented in Table 6 reinforce these findings across multiple evaluation metrics (MAFE, MSE, MAPE, and ) for all eight indices. Averaged across all indices, the RV feature set shows the strongest performance, achieving the lowest average errors (MAFE = 0.0117, MSE = 0.000281, MAPE = 30.68%) and the least negative (−0.028), confirming that past volatility proxy remains the most informative predictor of future volatility. The CP configuration performs moderately with higher error values (MAFE = 0.5866; MSE = 0.5235) but still substantially better than the V specification, which performs the worst by a wide margin across all metrics (MAFE = 0.8723; MSE = 0.8765; MAPE = 198.9%; = −2.400), indicating that volume alone contributes little meaningful predictive content. The P+V configuration markedly improves on the volume-only model and achieves error levels close to RV (MAFE = 0.0158; MSE = 0.000416), demonstrating that trading volume becomes informative primarily when contextualised by closing-price information.

Table 6.

Forecasting performance across node feature specifications.

Overall, the results show that the choice of node features substantially influences forecasting performance. While closing prices provide moderately informative signals for volatility prediction, trading volume alone offers a highly unstable and weak foundation for short-term forecasts, as reflected in its significant average errors and strongly negative values. In contrast, the volatility proxy and the combined price-and-volume specification deliver the highest accuracy, indicating that these feature sets best capture the dynamics relevant for the Temporal GAT model across multiple forecast horizons.

Remark 3 (Volume-Based Features).

The strongly negative values for volume-based models likely stem from the pronounced non-stationarity of raw trading volume, which exhibits long-term trends and structural shifts that standardization alone cannot remove. During the data preprocessing phase of this research, the volume is z-score normalized on a per-asset basis. This preprocessing addresses scale differences but does not correct underlying temporal instabilities that hinder generalization. As a result, volume provides a limited predictive signal for future volatility in the considered setting, leading to degraded out-of-sample performance. This explains the inferior performance of volume-based models relative to return- or volatility-based specifications and motivates the focus on volatility proxies as the primary predictive features.

5.5.3. Model Hyperparameters

In this section, we explore the sensitivity of the Temporal GAT model to variations in key hyperparameters, including hidden dimensions, number of heads, and learning rates. Adjusting these parameters is crucial in determining the model’s ability to generalize and capture complex relationships within the data. To identify the optimal configuration, we conducted a comprehensive grid search over a range of hyperparameter values, as described below.

- 1.

- Hidden Dimensions: We experimented with three values for the hidden dimensions: 32, 64, and 128. The hidden dimension defines the size of the feature space in the hidden layers of the model. A larger hidden dimension allows the model to learn more complex patterns, but can lead to over-fitting if not appropriately regularised.

- 2.

- Number of Heads in GAT Layer: We tested two values for the number of heads: 4 and 8. The number of heads controls the level of attention the model can distribute across different nodes in the graph, influencing the aggregation of information from neighbouring nodes.

- 3.

- Learning Rates: We evaluated three learning rates, 0.0001, 0.001, and 0.01, to determine the optimal step size for updating the model’s parameters. An appropriate learning rate ensures effective convergence during training while avoiding oscillations or premature stagnation.