Abstract

Gait recognition using wearable sensor data is crucial for healthcare, rehabilitation, and monitoring neurological and musculoskeletal disorders. This study proposes a deep learning framework for gait classification using inertial measurements from four body-mounted IMU sensors (head, lower back, and both feet). The data were collected from a publicly available, clinically annotated dataset comprising 1356 gait trials from 260 individuals with diverse pathologies. The framework, G-MASA-TCN (Gait Multi-Anchor, Space-Aware Temporal Convolutional Network), integrates multi-scale temporal fusion, graph-informed spatial modeling, and residual dilated convolutions to extract discriminative gait signatures. To ensure both high performance and interpretability, Integrated Gradients is incorporated as an explainable AI (XAI) method, providing sensor-level and temporal attributes that reveal the features driving model decisions. The framework is evaluated via repeated cross-validation experiments, reporting detailed metrics with cross-run statistical analysis (mean ± standard deviation) to assess robustness. Results show that G-MASA-TCN achieves 98% classification accuracy for neurological, orthopedic, and healthy cohorts, demonstrating superior stability and resilience compared to baseline architectures, including Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), Transformer neural networks, and standard TCNs, and 98.4% accuracy in identifying individual subjects based on gait. Furthermore, the model offers clinically meaningful insights into which sensors and gait phases contribute most to its predictions. This work presents an accurate, interpretable, and reliable tool for gait pathology recognition, with potential for translation to real-world clinical settings.

Keywords:

Multi-Anchor Space-Aware Temporal Convolutional Neural Network (MASA-TCN); Clinical Gait; Multimodal Data; Integrated Gradients; Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU); Transformer Neural Networks; Neurological; Orthopedic MSC:

37M10

1. Introduction

Human locomotion, particularly walking, represents a cornerstone of daily human function, requiring seamless integration among musculoskeletal, neuromotor, and sensory systems; alterations in gait biomechanics are highly sensitive biomarkers for underlying physiological and neurological pathologies [1,2]. The accelerating global demographic shift toward aging has precipitated a surge in gait-associated morbidities, encompassing osteoarthritis, post-stroke hemiparesis, Parkinsonian gait freezing, and sarcopenic decline [3,4]. Such disorders profoundly impair mobility, erode autonomy, and elevate susceptibility to falls, institutionalization, and premature death [5]. Consequently, proactive gait surveillance and early anomaly detection emerge as pivotal strategies in precision preventive medicine and neurorehabilitation [2,6].

Gait assessment traditionally relies on laboratory-based motion capture systems, force platforms, and instrumented treadmills [7,8]. While these tools provide precise biomechanical measurements such as joint angles, ground reaction forces, and step timing, their deployment is limited by high cost, technical complexity, and the inability to capture naturalistic, daily-life walking patterns [9,10]. Consequently, many clinically relevant gait abnormalities remain undetected until substantial functional decline occurs [11]. Wearable inertial measurement units (IMUs) have emerged as practical alternatives, capable of capturing continuous tri-axial acceleration and angular velocity data from key body segments such as the feet, shanks, or trunk [12,13]. These devices allow high-frequency motion data collection in real-world environments, enabling the detection of subtle gait deviations that may not manifest in laboratory assessments [2]. Recent studies validate the accuracy of IMUs against optical motion capture systems, demonstrating reliable measurement of stride length, cadence, and variability [14].

Despite their advantages, IMU datasets are high-dimensional, temporally complex, and often noisy, necessitating advanced computational approaches for meaningful interpretation [14,15]. Classical machine learning approaches such as support vector machines, random forests, and k-nearest neighbors rely heavily on handcrafted features, limiting their capacity to model complex, nonlinear temporal dependencies across multiple sensor axes [14]. Deep learning approaches, including convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, and Transformer architectures, have demonstrated superior capability in learning hierarchical features from raw time-series data [7,16,17]. CNNs are particularly effective for learning local temporal and spatial features, while LSTMs excel in modeling long-term temporal dependencies [16,17]. Transformers, utilizing self-attention mechanisms, can capture global dependencies across sequences but demand larger datasets and substantial computational resources [18,19].

Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCNs) offer an efficient alternative, employing dilated causal convolutions to capture long-range temporal dependencies while maintaining manageable computational cost [20,21]. However, standard TCNs often collapse multi-axis sensor data, losing critical spatial relationships such as inter-limb coordination and cross-joint interactions [14,22]. Preserving both spatial and temporal correlations is essential for accurate classification of gait conditions, particularly when subtle deviations reflect early-stage neurological or musculoskeletal impairments [11]. Insights from human-in-the-loop exoskeleton studies further underscore the importance of detailed spatiotemporal modeling. Exoskeleton-assisted walking has demonstrated that optimizing torque profiles based on real-time feedback can improve walking economy, reduce metabolic cost, and enhance gait symmetry [23,24]. Notably, adaptive multi-joint assistance based on continuous monitoring of joint angles and muscle activation has enabled personalized intervention strategies that improve mobility outcomes [25]. These findings emphasize the necessity of capturing multi-scale spatial and temporal features when designing AI-based gait assessment models.

The Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN) represents a recent advancement in deep learning for multivariate time-series classification, particularly in EEG for emotion recognition [26,27], and for action segmentation and detection [20]. The TCN extends conventional TCNs by incorporating multiple temporal anchors with distinct receptive fields, preserving both local and global temporal information while maintaining spatial correlations across sensor channels [28,29]. The model further integrates attention mechanisms to dynamically weigh contributions from each temporal and spatial anchor, enhancing feature interpretability and robustness [30,31]. This architecture has demonstrated superior performance in classifying complex spatial and temporal datasets compared to conventional CNN, LSTM, and standard TCN models [14,20].

In addition to spatial and temporal datasets, TCN and related architectures are increasingly applied in brain–computer interface (BCI) systems for emotion recognition, cognitive workload estimation, and neural decoding [28,29,32]. These applications highlight the versatility of multi-scale, space-aware temporal models in extracting meaningful features from high-dimensional, temporally structured signals [28,33]. For instance, deep convolutional and graph convolutional neural networks have been successfully applied to EEG datasets, capturing local–global interactions essential for reliable decoding of neural signals [32,34]. Transformer-based architectures have further improved performance by leveraging hierarchical attention mechanisms, enabling simultaneous modeling of spatial and temporal dependencies [27,29,35,36].

Despite its strong performance in modeling complex neural dynamics, Multi-Anchor Space-Aware Temporal Convolutional Network (MASA-TCN) has been used exclusively in EEG-based emotion recognition and has never been applied to human gait analysis [26]. This represents a notable gap, particularly given the critical role gait plays as an indicator of health, aging, fall risk, frailty, and neurological decline [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Wearable IMU-based gait analysis has become central to mobility assessment, enabling the extraction of stride parameters, joint coordination patterns, and dynamic balance metrics that are clinically meaningful and responsive to disease progression [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,37].

Introducing MASA-TCN into this domain offers several key advantages. First, its multi-anchor temporal convolutions are well suited to capture the fine-grained temporal structure of gait cycles, including stride timing, swing–stance transitions, and stride-to-stride variability features that are strongly linked to gait stability and fall risk [1,2,9]. Second, the model’s spatial-attention fusion provides a principled way to identify the most informative IMU channels and motion axes, supporting interpretable analysis of how specific body segments contribute to normal or pathological gait patterns, consistent with findings across sensor-based gait studies [10,11,12,13,14,15]. Third, MASA-TCN’s lightweight, TCN-driven architecture enables efficient real-time inference, aligning with advances in wearable-sensor gait tracking and activity recognition systems designed for continuous monitoring in real-world settings [21,38,39,40].

Taken together, these factors position MASA-TCN as a novel and technically well-justified architecture for gait analysis. Its proven ability to model multi-scale temporal–spatial patterns in EEG, combined with the clinical importance of gait and the growing maturity of wearable sensing, provides a strong foundation for applying MASA-TCN to gait datasets for the first time. This also paves the way for integrating MASA-TCN with XAI methods to deliver transparent, clinically interpretable gait assessments, an essential requirement for future healthcare and mobility-monitoring applications.

Wearable exoskeleton studies have further informed the design and evaluation of AI-based gait models. For instance, adaptive hip exosuits have been shown to reduce metabolic cost during walking and running, while ankle and knee exoskeletons improve stability and joint-specific assistance [24,25,41]. Human-in-the-loop optimization enables dynamic adjustment of torque profiles based on user-specific biomechanics, emphasizing the importance of accurate multi-channel sensor modeling [42]. These findings reinforce the notion that effective AI-based gait analysis must account for both local joint-level dynamics and global locomotor coordination, which MASA-TCN accomplishes through its multi-anchor, space-aware design [26,43]. This study’s contributions, as shown in Figure 1, are the following:

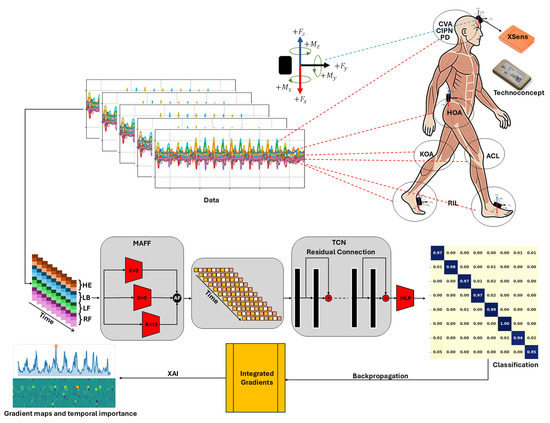

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed G-MASA-TCN framework, consisting of three components: the MAAF block, the TCN block, and the classification block. IMU sensors are positioned using Velcro bands on the lower back (L5), forehead, and both feet (upper sensors: XSens; lower sensors: Technoconcept). Example gait sub-segments are shown for multiple conditions: HOA, KOA, ACL, CVA, PD, CIPN, and RIL. The parameter in the SAT module denotes the temporal kernel length. Backpropagation is included for XAI Gradient maps and temporal importance. Where red dashed lines collected signal locations, black arrows data flow in the framework.

- Development of G-MASA-TCN, a unified deep learning model for multi-condition gait classification and individual identification.

- Space-aware temporal layers for spatial–spectral learning across multiple IMU channels.

- Multi-anchor attentive fusion for capturing dynamic gait events at multiple temporal scales.

- Evaluation on 260 real patients with eight clinically confirmed conditions, demonstrating high classification and identification accuracy.

- Comparative analysis with standard TCN, Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), and Transformer neural network-based architectures.

G-MASA-TCN offers a unified approach for analyzing human gait, capturing complex spatiotemporal patterns, and enabling accurate, clinically relevant classification and identification. It advances automated gait analysis by overcoming limitations of prior deep learning methods, providing both rich spatial–temporal modeling and high recognition accuracy.

The article is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the experimental design, participants, gait signal data, and preprocessing methods. It also presents the G-MASA-TCN with the deep neural network architecture. Section 3 and Section 4 present and analyze the results obtained. Finally, Section 5 offers conclusions and suggests potential directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

This study employs a publicly accessible dataset titled Clinical Gait Signals with Wearable Sensors from Healthy, Neurological, and Orthopedic Cohorts [37]. The dataset includes multimodal gait recordings captured using four inertial measurement units (IMUs) to analyze human locomotion across multiple clinical populations.

Participants were recruited from hospitals affiliated with the Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Paris, France and the Hôpital d’Instruction des Armées, France. The sample comprised both healthy volunteers and patients from neurological and orthopedic departments. The control group, healthy subjects (HSs), included 73 adults (41 males, 32 females; ages 18–87) with no medical conditions confirmed through clinical examination. The patient population was divided into two major cohorts:

- The orthopedic cohort (44 participants) with diagnoses of hip osteoarthritis (HOA), knee osteoarthritis (KOA), or anterior cruciate ligament injury (ACL).

- The neurological cohort (143 participants) encompassing cerebrovascular accident (CVA), Parkinson’s disease (PD), chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN), and radiation-induced leukoencephalopathy (RIL).

Each participant underwent a standardized clinical assessment using established scoring systems corresponding to their condition (see Table 1). Differences in age distributions across cohorts reflect disease-specific characteristics rather than sampling bias. All procedures complied with ethical standards approved by the Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile de France II (CPP 2014-10-04 RNI). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants for data collection and sharing [37].

Table 1.

Summary of clinical or radioclinical scores calculated by the physician for each pathology. HOA: hip osteoarthritis; KOA: knee osteoarthritis; ACL: anterior cruciate ligament injury; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; PD: Parkinson’s disease; CIPN: chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy; RIL: radiation-induced leukoencephalopathy, HSs: healthy subjects [37].

Sensor Configuration

Four IMU sensors were positioned on the head (HE), lower back (LB), left foot (LF), and right foot (RF) (see Table 2) using adhesive straps as shown in Figure 1. Two hardware types were used: XSens and Technoconcept I4 Motion (see Figure 1), both functionally equivalent in capturing time-series acceleration and angular velocity signals. Sensors operated at a sampling frequency of 100 Hz, with full synchronization before each session [37]. The recorded data are presented for each class in this dataset in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Table 2.

IMUs Sensor distribution and recorded data for reading for head, back, right foot, and left foot.

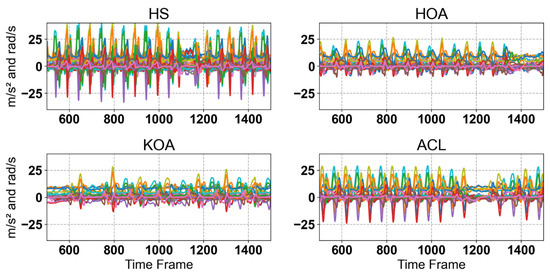

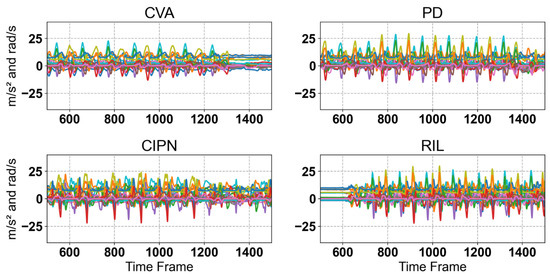

Figure 2.

Raw IMUs Sensor singles for Hs, HOA, KOA, and ACL. Each plot shows multiple gait cycles for the corresponding class, illustrating the variability across samples. As can be seen, there are noticeable differences in signal patterns between the classes, reflecting variations in gait dynamics associated with different musculoskeletal conditions.

Figure 3.

Raw IMU sensor singles for CVA, PD, CIPN, and RIL. Each plot shows multiple gait cycles for the corresponding class, illustrating the variability across samples. As can be seen, there are noticeable differences in signal patterns between the classes, reflecting variations in gait dynamics associated with different musculoskeletal conditions.

2.2. Data Processing Pipeline

The raw multivariate gait signals were processed through a structured pipeline to ensure consistency across subjects, robustness against inter-trial variability, and suitability for temporal modeling using the G-MASA-TCN architecture. Each trial in the dataset initially consisted of a variable-length sequence of T time steps sampled at 100 Hz, with 36 synchronized sensor channels capturing triaxial acceleration, free acceleration, and gyroscope readings from multiple body locations. Because gait speed differed significantly across clinical cohorts including HSs, HOA, KOA, ACL, PD, CVA, CIPN, and RIL, the resulting signal lengths also varied substantially. Empirically, the longest trial contained 18,639 frames, whereas the shortest contained 2490 frames. To manage this heterogeneity, two complementary preprocessing strategies were adopted for model training and evaluation.

2.2.1. Experiment 1: Zero-Padding Strategy (Full-Length Alignment)

In the first strategy, each trial was temporally aligned by zero-padding shorter sequences up to the maximum observed length . Formally, for a trial , the padded sequence is defined as

This approach preserved the full temporal structure of each trial and enabled the G-MASA-TCN to model complete gait cycles without discarding information. The padded sequences maintained the two-dimensional temporal–spatial organization of the data, consistent with the network’s convolutional design

2.2.2. Experiment 2: Fixed-Length Segmentation Strategy (500-Frame Windows)

In the second strategy, no temporal padding was applied. Instead, each variable-length trial was divided into consecutive non-overlapping sub-segments of frames with the fixed length :

Because the sampling rate was 100 Hz, each 500-frame window corresponded to a 5 s segment of gait motion. Each segment retained its original spatial–temporal structure as a matrix of size . This method provided the G-MASA-TCN with uniformly sized windows while preserving the natural variability of gait patterns without introducing padding artifacts. Both preprocessing strategies were used independently for model training, allowing direct comparison of classification accuracy across full-length padded sequences and fixed-length unpadded segments.

2.2.3. Experiment 3: Subject-Level Identification via Gait Patterns

To ensure accurate prediction of the eight gait classes, encompassing neurological, orthopedic, and healthy cohorts, the model was evaluated on its ability to differentiate the gait patterns of 260 individual subjects as a biometric task. Gait analysis was approached as a subject identification problem, analogous to biometric fingerprint recognition. Each sample in the dataset is associated with a unique subject ID, and the model was trained to classify gait sequences according to their originating subject. Formally, let denote the label matrix, where the first column encodes the subject ID (), and the additional columns may encode metadata such as gait class. The dataset consists of 260 distinct subjects. Unlike traditional class-based partitioning, the G-MASA-TCN model is trained to distinguish among all 260 subjects simultaneously, learning unique gait signatures for each individual. Each subject is treated as a separate class: . The training and evaluation process uses the full set of subjects, enabling the model to associate specific spatiotemporal gait patterns with their corresponding subject IDs. By framing gait sequences as subject-specific biometric identifiers, the model can predict the subject from previously unseen gait sequences, akin to a forensic system linking latent fingerprints to a known individual. This subject-level identification framework ensures that the model’s performance reflects its ability to capture individual-specific gait characteristics, rather than only generic class differences. Such an approach provides a strong foundation for extending the model in healthcare applications, enabling reliable classification across multiple gait-related conditions and cohorts.

2.2.4. Standardization of Training and Testing Data

Before feeding the signals into the G-MASA-TCN, each feature channel was standardized using statistics computed only from the training data. For training data , the mean vector and standard deviation vector across the temporal and sample dimensions were computed as

To avoid division by zero, channels with were replaced with 1. The standardized data was computed as

Standardization ensures that each sensory channel contributes proportionally during con volution, stabilizes gradient flow, and improves training convergence by rescaling all features to comparable ranges.

2.2.5. Final Data Representation for G-MASA-TCN

After segmentation, subject-level splitting, and standardization, each sample fed into the G-MASA-TCN has the shape

where

- for zero-padded full-length trials, for a total of 1356 samples;

- for fixed-length segmented windows, for a total number of 7455 samples.

This consistent representation aligns with the G-MASA-TCN’s multi-anchor spatial–temporal convolutional layers, which operate across the temporal dimension while jointly capturing inter-channel spatial dependencies.

2.2.6. Real-World IMU Data for Compression

Although the G-MASA-TCN model is primarily developed for clinical gait analysis, specifically to differentiate between neurological, orthopedic, and healthy cohorts, it still requires validation under more generalized data and real-world scenarios. Therefore, without additional experimentation, we evaluate the applicability of the proposed model to human gait performance on irregular and uneven surfaces and during natural everyday walking in an urban environment as shown in Figure 4. For the real-world irregular surface dataset [44], the data were collected from 30 healthy participants (15 males and 15 females) who wore six IMU sensors placed on the forearms, thighs, ankles, and lower back while walking across nine different outdoor surface conditions (e.g., paved, grass, uneven stone, ramps, stairs) with multiple trials per participant covering a range of terrains and subtle gait pattern variations [44]. All subjects in the dataset were healthy; subject identity was used as the classification label in our experiments. We applied the same preprocessing procedure to these data: the raw IMU signals were segmented into fixed-length sequences of 500 steps, as described in Section 2.2.2, followed by assigning unique subject IDs as class labels according to Section 2.2.3. Finally, the segmented sequences were standardized as outlined in Section 2.2.4, resulting in a structured dataset suitable for evaluating the generalizability of the G-MASA-TCN model on non-clinical gait data.

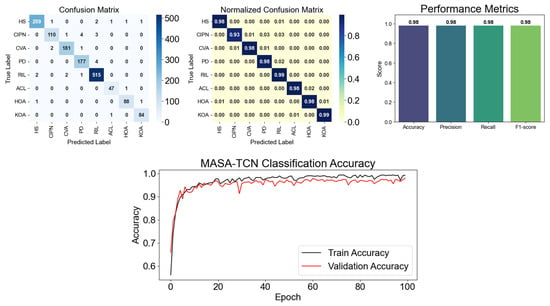

Figure 4.

G-MASA-TCN classification results for Experiment 2 using the fixed-length segmentation strategy with 500-frame windows. The figure shows the confusion matrix for all classes, highlighting the normalized accuracy of predicted samples compared to true positives. Performance metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score are also presented. Additionally, the training and validation learning curves illustrate the model’s performance across epochs, demonstrating proper alignment and indicating the absence of overfitting.

2.3. G-MASA-TCN: A Gait-Multi-Scale Space-Aware Temporal Convolutional Network for Gait Pathology Classification

This study classifies eight gait conditions—HSs, HOA, KOA, ACL, PD, CVA, CIPN, and RIL—using multivariate time series collected from four IMUs positioned on the head (HE), lower back (LB), left foot (LF), and right foot (RF). Each IMU recorded tri-axial acceleration, gravity-compensated (free) acceleration, and angular velocity, resulting in input channels per time step. The input tensor is defined as

where is the batch size and corresponds to 5 s of data at 100 Hz sampling rate. To address this challenging multi-class classification task, an adapted version of the Multi-Anchor Space-Aware Temporal Convolutional Network (MASA-TCN), originally proposed in [26] for EEG-based emotion recognition, was employed. The model is specifically tailored to capture multi-scale temporal dynamics, inter-limb coordination, and causal real-time inference all critical for clinical gait assessment.

2.3.1. SAT Layer: Space-Aware Temporal Feature Extraction

The foundational building block of G-MASA-TCN is the Space-Aware Temporal (SAT) layer, designed to extract local temporal patterns while preserving spatial relationships across sensor channels, as shown in Figure 1. Unlike traditional 1D convolutions applied independently per channel, the SAT layer treats the input as a 2D feature map, enabling joint modeling of sensor location and signal dynamics. Given an input , the SAT layer proceeds as follows:

- Reshaping for 2D Convolution:

- Context Convolution (Multi-Channel Temporal Modeling): A 2D convolution with the kernel size and dilation is applied:

- This operation extracts temporal patterns of length across all 36 channels simultaneously, with causal padding ensuring no future information leakage. The output is cropped to the original length:

- Spatial Mixing via 1 × 1 Convolution: A pointwise convolution mixes information across the feature maps:

- Normalization and Regularization:

Traditional 1D convolutions treat each IMU channel independently, ignoring anatomical and functional relationships (e.g., head–trunk coupling in PD, asymmetric foot loading in KOA). The SAT layer’s 2D kernel spanning all channels enables the network to learn cross-sensor dependencies, for instance, compensatory head motion in response to lower limb instability. The use of causal dilated convolution ensures the model can be deployed in real-time clinical settings, where future frames are unavailable.

2.3.2. MAAF Block: Multi-Scale Adaptive Feature Fusion

Gait cycles exhibit hierarchical temporal structures: micro-events (heel-strike, toe-off), step-level patterns (~1 s), and stride-level symmetry (~2 s). To capture multi-scale dynamics, the Multi-Anchor Adaptive Fusion (MAAF) block, illustrated in Figure 1, is employed, which executes three SAT layers in parallel with kernel sizes :

The outputs are concatenated:

A 1 × 1 fusion convolution learns to adaptively weight and combines multi-scale representations:

This is followed by batch normalization and ReLU:

Rationale for Multi-Scale Design

- Kernel = 3 (~30 ): Captures rapid acceleration spikes during foot contact.

- Kernel = 5 (~50 ): Models mid-stance and push-off phases.

- Kernel = 15 (~150 ): Encodes step-level transitions and inter-limb coordination.

This inception-style parallelism allows the model to represent gait at multiple temporal resolutions without increasing depth, improving robustness to stride variability seen in pathological gait (e.g., shuffling in PD, limping in HOA).

2.3.3. Residual Temporal Convolutional Blocks

The MAAF (See Figure 1) output is squeezed to and processed by three residual dilated 1D convolutional blocks with increasing dilations: . For the -th block,

In this formulation,

- represents the nonlinear dilated convolutional transformation;

- denotes the residual connection, which either performs a projection (when channel dimensions differ) or passes the input directly;

- The block output is obtained by summing the transformed output and the residual pathway.

With for all blocks, the effective receptive field after three layers is

However, when combined with SAT dilation () and multi-scale kernels, the total receptive field exceeds 1.2 s, sufficient to model full gait cycles. Why is the residual TCN used? Recurrent networks (LSTM, GRU) suffer from vanishing gradients and slow inference. Dilated TCNs offer exponential receptive field growth, parallel training, and constant-time inference ideal for embedded clinical devices. Weight normalization and residual connections stabilize training of deep temporal models.

2.3.4. Classification Head and Training

After the final residual TCN block, the feature map contains rich temporal representations that encode multi-scale gait dynamics across all sensor channels. To produce a single prediction per input sequence, global average pooling is applied along the temporal dimension, summarizing the entire 5 s gait segment into a compact fixed-length vector:

This operation not only reduces dimensionality but also enforces translation invariance across the gait cycle, making the model robust to variations in stride timing a common challenge in pathological gait where cadence and phase durations differ significantly between conditions. The pooled representation is then passed through a fully connected layer with the weight matrix and bias , producing class logits for the eight target pathologies:

During training, the model is optimized end-to-end using the cross-entropy loss, which measures the discrepancy between predicted probabilities and ground-truth labels:

The Adam optimizer is employed with an initial learning rate of , enabling stable convergence even with the high-dimensional 36-channel input. Dropout with a probability of 0.1 is consistently applied throughout the network to prevent overfitting, particularly important given the relatively small sample sizes typical in clinical gait studies. This training paradigm ensures that the model learns discriminative features directly from raw IMU signals without requiring hand-crafted gait parameters such as stride length, stance time, or symmetry indices.

2.4. Why G-MASA-TCN for Gait Pathology Classification?

Pathological gait is characterized by complex, multi-scale temporal alterations. For instance, PD often manifests as reduced step length and increased cadence variability at the sub-step level, while hemiparetic gait following CVA introduces pronounced asymmetry over full stride cycles. The MAAF block, with its parallel SAT layers using kernel sizes of 3, 5, and 15, captures hierarchical dynamics: short kernels detect rapid acceleration transients during foot contact, medium kernels model mid-stance and propulsion phases, and longer kernels encode inter-limb coordination and stride-level symmetry. The effective receptive field of a single SAT layer with kernel size and dilation is

yielding 5, 9, and 29 frames, respectively, for . After adaptive fusion and the subsequent residual TCN stack with the dilations and kernel size 3, the total receptive field expands exponentially:

This covers > 1.2 s at 100 Hz sampling sufficient for multiple gait cycles without explicit event detection pipelines [26]. Second, the spatial arrangement of IMU sensors on the head, lower back, and bilateral feet forms a natural anatomical hierarchy that influences gait stability and compensation strategies. In healthy walking, trunk and head motion are tightly coupled with lower limb kinematics; in contrast, patients with HOA may exhibit increased pelvic tilt to reduce joint loading, while those CIPN display reduced distal coordination. The SAT layer’s 2D convolution with kernel height equal to all 36 channels jointly models cross-sensor dependencies, outperforming channel-independent 1D convolutions that miss inter-segment coordination [38].

Third, clinical deployment demands real-time, causal inference. Wearable gait monitoring systems must provide immediate feedback during ambulatory assessments or fall risk evaluation. The entire G-MASA-TCN architecture—causal padding in SAT layers, dilated convolutions with increasing rates, and absence of recurrent units—ensures that predictions at the time depend only on inputs :

Equation (25) enables low-latency inference on edge devices [39]. Furthermore, the model strikes an effective balance between expressiveness and efficiency. With approximately 0.92 million parameters, it is substantially lighter than hybrid ConvLSTM architectures, which often exceed 1.2 million parameters due to recurrent gating mechanisms. The residual TCN blocks, enhanced with weight normalization and PReLU activations, facilitate stable training of deep temporal hierarchies without gradient vanishing, a common issue in long-sequence gait data. Finally, the proven generalization of MASA-TCN from EEG emotion recognition to IMU-based movement analysis underscores its robustness to noisy, high-dimensional, multivariate time series, a hallmark of real-world sensor data affected by motion artifacts, sensor drift, and environmental interference [26].

2.5. Baseline Model Architectures

To establish a fair performance comparison, the proposed G-MASA-TCN was evaluated against three widely used sequence-modeling architectures: a Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN), Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), and Transformer encoder. The first baseline, a TCN model, follows the design introduced in [45], which employs stacked dilated causal convolutions to efficiently expand the receptive field and capture long-range temporal dependencies without recurrence. While TCNs provide strong temporal modeling capabilities, they do not capture spatial correlations across IMU channels. The second baseline is a deep bidirectional GRU network, inspired by [46], which models temporal sequences through gated recurrence and hidden-state transitions. GRUs are effective for sequential data but struggle with long sequences and lack the ability to model multi-scale gait variations, especially when compared to convolutional approaches. The third baseline uses a Transformer encoder architecture introduced in [47], leveraging multi-head self-attention to model global dependencies across all time steps. Although Transformers excel at long-range modeling, they require larger datasets to avoid overfitting and do not inherently encode temporal priors or spatial sensor interactions. In contrast to these baselines, the proposed G-MASA-TCN integrates multi-anchor spatial–temporal filtering, graph-aware feature learning, and residual dilated convolutions, enabling it to capture fine-to-coarse gait dynamics and inter-sensor dependencies beyond those modeled by the TCN, GRU, or Transformer baselines.

2.6. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) for G-MASA-TCN

Although G-MASA-TCN provides state-of-the-art performance in classifying gait disorders, interpretability remains essential, especially in clinical and biomechanical applications where understanding model makes a particular decision is as critical as the prediction itself. To enhance transparency, the model integrates an explainable AI (XAI) framework centered on Integrated Gradients (IG), a mathematically principled attribution method introduced in [48]. IG was selected over alternative interpretation techniques such as Saliency Maps, SmoothGrad [49], Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP), and SHAP because it satisfies key axioms required for reliable medical decision support: sensitivity, implementation invariance, linearity, and completeness. Most gradient-based methods fail to satisfy these axioms [50], while perturbation-based methods such as SHAP or LIME are computationally expensive for high-dimensional time-series models and often produce unstable results. IG, in contrast, provides smooth, theoretically grounded attributions that align uniquely well with G-MASA-TCN’s multi-anchor temporal representation, making it the most suitable XAI choice for clinical gait modeling.

Integrated Gradients measures how much each input feature contributes to the model’s output by integrating the gradients along a straight-line path between an input, , and a baseline, (typically a zero or mean sensor sequence). For an input feature , the IG attribution is defined as

where is the G-MASA-TCN output logit for the predicted class. In practical implementations, the integral is approximated using interpolation steps:

For G-MASA-TCN, each input is a multichannel IMU time series:

where denotes the temporal window and indicates the number of sensor channels. IG backpropagates its gradients through every component of the architecture including the Multi-Anchor Attention Fusion (MAAF), the residual dilated TCN blocks, and the temporal global pooling stage, allowing the attribution map to reflect the true contribution of early spatial–temporal convolutional filters as well as deeper receptive-field expansions. This enables G-MASA-TCN to reveal class-specific reliance on short-range vs. long-range temporal filters, biomechanically meaningful gait events such as heel-strike or toe-off, and fine-grained cross-sensor dependencies. The resulting IG attribution tensor

is used to construct two complementary interpretability visualizations. Feature importance is computed by averaging the absolute attributions over time:

This allows identification of the dominant sensor channels for each gait pathology. Temporal importance is obtained by averaging the absolute attributions across selected sensor channels:

This highlights which gait-cycle segments (e.g., stance, swing, transition) exert the strongest influence on the model’s classification decision. Together, these visualizations form clinically meaningful sensor–time heatmaps that reveal how MASA-TCN grounds its predictions in biomechanically relevant features rather than noise or spurious correlations. Integrated Gradients therefore ensures both local (sample-level) and global (class-level) interpretability, enabling clinicians and researchers to validate, audit, and trust the G-MASA-TCN model. Its mathematical guarantees, stability, and compatibility with high-resolution temporal-convolutional models make it superior to alternative XAI methods for gait-pathology analysis.

3. Results

To ensure that the evaluation of all models was statistically reliable, reproducible, and free from artifacts caused by dataset shuffling, each experiment was repeated five times using different random seeds and a subject-level 5-fold cross-validation, with 70% of the data used for training, 10% for validation, and 20% for testing in each fold. This combined procedure allows assessment of model variance, robustness, and sensitivity to initialization, while maintaining rigorous, non-overlapping test partitions for unbiased evaluation. Model training was conducted on Google Colab cloud infrastructure using an NVIDIA GPU, with an average training time of approximately 5 min, while testing and inference evaluations were performed on a local workstation equipped with an Intel Core i7 (10th generation) CPU to assess deployment feasibility on standard hardware. For each experiment, two complementary sets of results are reported: (1) the best-performing run in terms of validation accuracy, including the confusion matrix, precision, recall, F1-scores, overall accuracy, and full training/validation accuracy curves; (2) aggregate statistics across all five runs, represented by the mean confusion matrix and corresponding standard deviations. To further visualize the model’s ability to cluster gait dynamics across the eight classes (HSs, HOA, KOA, ACL, PD, CVA, CIPN, and RIL), a t-SNE projection of the learned embeddings is provided for each experiment.

Because diagnostic applications require not only strong predictive performance but also transparent decision-making, these quantitative results are complemented by a comprehensive explainable AI (XAI) analysis. This interpretability framework reveals the internal spatiotemporal representations learned by each model and identifies the most influential sensor channels and gait-cycle segments contributing to classification. Together, the statistical evaluation and XAI visualizations provide a complete and trustworthy assessment of both model accuracy and interpretability in biomechanical and clinical contexts. In the following sections, the results of the training and evaluation strategies introduced, followed by an evaluation using the Integrated Gradients (IG) XAI method.

3.1. Experiment 1: Zero-Padding Strategy

This experiment investigated the effect of zero padding on modeling variability in gait duration among participants. Since real-world gait recordings vary in length due to differences in stride cycles, cadence, mobility level, and pathological conditions, all sequences were standardized to the global maximum length by padding shorter sequences with zeros. This ensured that architectures such as the TCN, Transformer, and the GRU could process all trials in a unified tensor format while preserving complete temporal dynamics. However, the impact of padding on learning stability varied substantially across models. Across the five independent seeds (see Table 3), the baseline TCN reached , confirming that conventional dilated convolutions can capture long-range temporal dependencies but remain sensitive to variation in gait rhythm. The Transformer, however, performed considerably worse at , likely due to its positional-encoding dependence and limited ability to regulate noisy or padded temporal segments. The GRU exhibited the weakest performance at , which suggests that recurrent architectures face difficulty maintaining stable hidden-state transitions when padding disrupts stride periodicity.

Table 3.

Mean and standard deviation with different random seed for each experiment for the classification of gait with 70% for training, 10% for validation, and 20% for testing.

In sharp contrast, the proposed G-MASA-TCN achieved 95.2% ± 0.8%, not only outperforming all baseline models but also exhibiting extremely low variance across all five seeds. This demonstrates the architecture’s stability under variable-length gait conditions and its ability to extract discriminative temporal cues from complete, natural gait cycles. The multi-anchor temporal filters of MASA-TCN allow the model to analyze gait at multiple temporal scales simultaneously, enabling it to capture subtle abnormalities such as reduced stride length in HOA and KOA, elevated gait asymmetry in ACL and CVA, and tremor-induced high-frequency fluctuations in PD. Moreover, the spatial-attention fusion mechanism highlights the most informative IMU channels and axes when distinguishing neuropathic gait alterations in CIPN and central motor disruption patterns in RIL. The results of this experiment include the confusion matrix for the best seed run, the mean confusion matrix across all runs, accuracy/precision/recall/F1 metrics, and the complete training and validation accuracy curves are summarized in Figure 4. The data show that G-MASA-TCN manages temporal irregularities caused by pathology-specific gait disruptions, supporting its advantage over architectures with limited spatial adaptivity or weaker temporal stability.

3.2. Experiment 2: Fixed-Length Segmentation (500-Frame Windows)

This experiment evaluated the impact of fixed-length segmentation, which eliminated zero padding altogether. Gait signals were windowed into non-overlapping 500-frame segments, corresponding to approximately 5 s of motion. This segmentation reduced temporal variability between samples, thereby stabilizing the learning process by presenting the models with consistent temporal structures. Under this standardized alignment, the baseline models improved significantly across all five seeds, as shown in Table 3. The traditional TCN reached , the Transformer achieved , and the GRU improved markedly to . These gains reflect the benefit of ensuring that each input segment contained a comparable number of gait cycles, a crucial factor given the distinct stride dynamics across HSs, HOA, KOA, and PD and the irregular timing patterns in ACL, CVA, CIPN, and RIL.

The G-MASA-TCN once again delivered the strongest performance, achieving 96.8% ± 1.2% across the five seeds. This marks an improvement over Experiment 1 and indicates that MASA-TCN benefited from clean, uniformly segmented gait windows in which stride-level micro-patterns were preserved without padding artifacts. The multi-scale anchoring mechanism was especially advantageous here: it captured the interaction between low-frequency gait-cycle components (e.g., stance–swing transitions) and high-frequency pathological markers (e.g., PD tremor- or CIPN-related proprioceptive instability). The spatial-attention module also became more effective in this setting, consistently highlighting hip-mounted and shank-mounted IMU axes that strongly differentiate HOA, KOA, and ACL conditions. The results of this experiment, including detailed confusion matrices for the best run, the aggregated mean matrices, and the learning curves, are displayed in Figure 4. The improvement across all architectures confirms that fixed-length segmentation fostered more stable temporal learning, but G-MASA-TCN maintained a decisive performance advantage, approaching near-perfect discrimination across all eight gait classes.

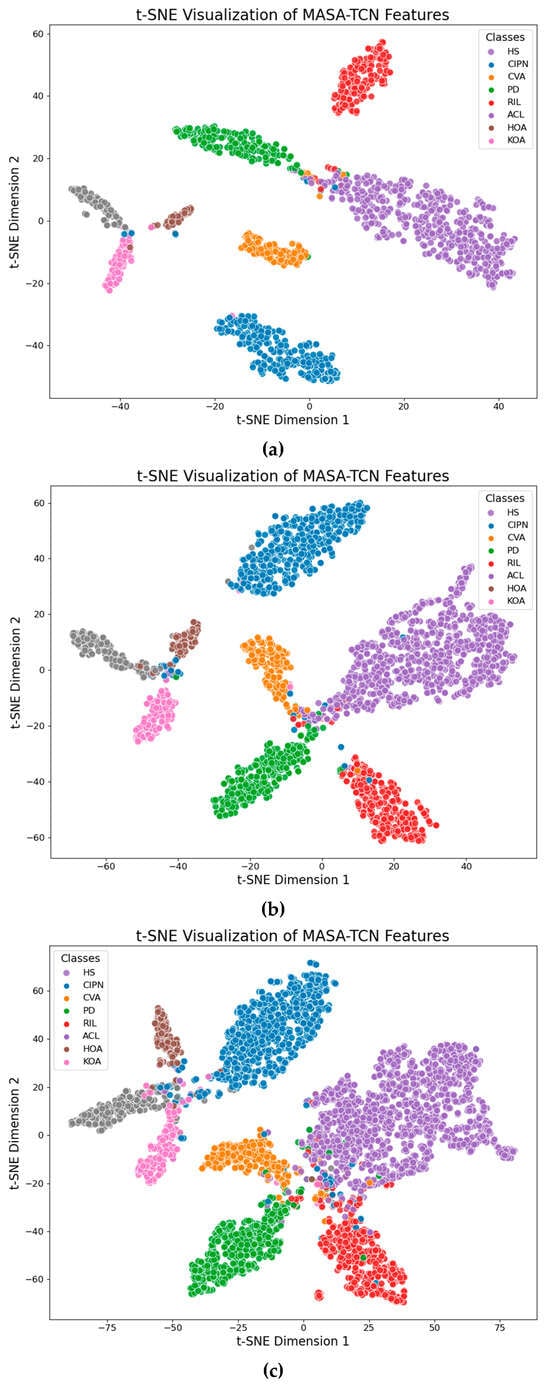

The models were initially trained and validated using 70% of the available dataset, with 60% allocated for training and 10% reserved for validation, while the remaining 30% was held out for testing. This initial split enabled optimization of model parameters and hyperparameters while providing an unbiased evaluation of performance on unseen data. Given that G-MASA-TCN achieved the highest predictive performance among all architectures, further experiments were conducted to evaluate its robustness across different training-to-testing ratios. Specifically, the model was retrained on 60% of the data and tested on the remaining 40%, then trained on 40% and tested on 60%, and finally trained on 30% with testing on 70% of the dataset. Across all these splits, the observed changes in model accuracy were minimal and statistically insignificant, which can be attributed to the large size of the dataset comprising 7455 samples and the use of fixed-length segmentation of 500 samples per segment, which ensured consistent input representations for training and testing. The results for each split are presented not only in terms of standard performance metrics but also visually through t-SNE clustering of the predicted eight gait classes (HSs, HOA, KOA, ACL, CVA, PD, CIPN, RIL), demonstrating clear separation and alignment with clinical groupings as shown in Figure 5. These analyses collectively confirm the stability, robustness, and generalization capability of G-MASA-TCN across varying training data sizes.

Figure 5.

G-MASA-TCN t-SNE plots for different data split. (a) Training used 70% and remaining 30% was held out for testing. (b) Training used 60% and remaining 40% was held out for testing. (c) Training used 30% and remaining 70% was held out for testing.

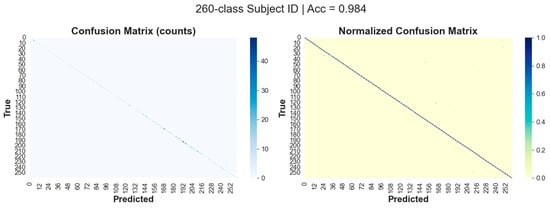

3.3. Experiment 3: Subject-Level Identification via Gait Signatures

This experiment explored a fundamentally different problem setup: subject identification from gait signals. Unlike pathology classification, the models were tasked with identifying 260 individual subjects, requiring each architecture to learn unique, person-specific gait signatures. This scenario emphasized subtle spatiotemporal features that remained consistent across trials, despite variations in pathology or sensor noise. Using 500-frame segments, as shown in Table 3, the GRU achieved 76% ± 3.3%, outperforming the Transformer (62% ± 4.1%) but slightly below the TCN (79% ± 3.5%). The GRU’s performance reflects its suitability for capturing individualized rhythmic patterns. However, the G-MASA-TCN again achieved the highest performance, reaching 96.4% ± 2.1% across the five seeds.

To further evaluate generalization and mimic biometric identification scenarios, an additional test was conducted in which 10 subjects were completely removed from the training set and treated as unknown “imposters” during testing. G-MASA-TCN returned zero predictions for these unseen subjects, indicating that it did not falsely classify unknown individuals as any of the enrolled subjects. This result mirrors real-world biometric systems, where unknown individuals are correctly recognized as imposters, demonstrating that G-MASA-TCN reliably captures subject-specific gait signatures without overfitting to the training population.

This result highlights architecture’s exceptional capability to learn high-resolution gait signatures, capturing discriminative temporal cues that differ across individuals even within the same pathology class. Such signatures include personalized cadence, foot–ground contact profiles, habitual asymmetries, and joint-coordination rhythms. The multi-anchor mechanism, by analyzing the gait signals at varying temporal scales, enables the model to discover nuanced personal stride features that conventional TCN, Transformer, and GRU architectures fail to isolate consistently. The spatial attention module complements this by selecting the most identity-relevant IMU axes, often focusing on lateral acceleration and angular velocity channels associated with personalized stride lateralization. The results for this experiment, including the best-run confusion matrix, mean confusion matrix, and complete evaluation metrics, are presented in Figure 6. The t-SNE plots reveal well-separated clusters, demonstrating that G-MASA-TCN learns highly discriminative representations of individual gait signatures, confirming its promise for gait biometrics.

Figure 6.

G-MASA-TCN classification results for Experiment 3 using the fixed-length segmentation strategy (500-frame windows) for ID classification, showing the confusion matrix.

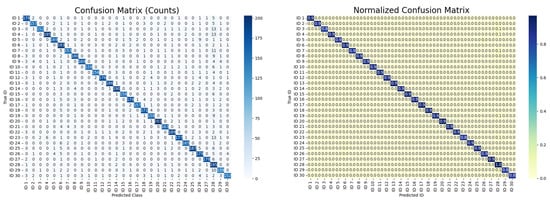

3.4. Experiment 4: 5-Fold Cross Validation

In this experiment, all models were trained and evaluated using 5-fold cross-validation. In each fold, two subjects from each class were held out for testing, while the remaining subjects were used for training. The test subjects were randomly selected under the constraint that no subject was included in the testing set more than once across all five folds.

The choice of using two test subjects per class was motivated by the limited number of available subjects in the HO, KOA, and ACL classes, each containing fewer than 20 subjects. Selecting two subjects per fold provided a more reliable and balanced evaluation under these constraints. The testing results, reported in Table 3, indicate that the proposed G-MASA-TCN with fixed-length inputs achieved the best overall performance. Specifically, it attained a peak accuracy of 96.1%, with a mean accuracy of 94.3% ± 1.8% across the 5-fold cross-validation. This outcome further confirms the consistency of the results obtained in Experiments 1 and 2.

3.5. Experiment 5: Subject-Level Identification via Real-World Gait Signature Data

To evaluate the generalization capability of the proposed G-MASA-TCN model, experiments were conducted on two real-world IMU-based gait datasets (see Section 2.2.5): irregular and uneven surface walking 30 subjects and natural everyday walking in an urban environment. For this dataset, the models was trained twice under two evaluation protocols. In the first experiment, the model was trained to classify all subjects, where each subject was treated as an independent class. This setup evaluated the model’s ability to capture subject-specific gait signatures under non-clinical, real-world walking conditions. The obtained classification performance demonstrates that the proposed architecture can effectively learn discriminative gait representations from IMU data recorded on uneven and irregular surfaces as well as during natural urban walking. The results, as reported in the confusion matrix in Figure 7, show that the best-performing model achieved 93% accuracy in predicting the classes of each subject. Across the five random-seed repetitions, the model obtained a mean accuracy of 91% ± 2%, demonstrating consistent performance and reliability across different data splits.

Figure 7.

G-MASA-TCN classification results for Experiment 5 using the fixed-length segmentation strategy (500-frame windows) for ID classification of real-world gait signature data, showing the confusion matrix.

In the second experiment, an imposter detection protocol was employed to further assess G-MASA-TCN model robustness. Five subjects were randomly selected and completely excluded from the training set. During testing, the model was required to identify these unseen subjects as imposters, i.e., subjects not belonging to any of the known classes learned during training and it return zero F1 score. This experiment evaluated the model’s ability to generalize beyond trained identities and to detect unfamiliar gait patterns encountered in real-world scenarios.

The primary objective of this validation was twofold: to assess the ability of G-MASA-TCN to capture human gait characteristics outside the clinical environment and to evaluate its robustness in modeling gait patterns during walking on uneven, irregular, and uncontrolled surfaces. The quantitative results for the dataset experimental protocol are summarized in Table 3. Overall, the results confirm that the proposed G-MASA-TCN model maintains strong performance in real-world settings, highlighting its potential applicability for robust gait modeling beyond controlled clinical conditions.

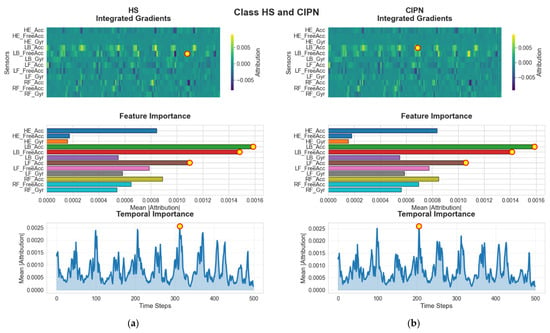

3.6. XAI Evaluation

The explainability analysis based on Integrated Gradients (IG) offers a comprehensive view of how the G-MASA-TCN model interprets sensor data to classify gait patterns across eight distinct conditions. By incorporating multiple visualization techniques including sample-level IG heatmaps, global feature importance bar plots, and temporal relevance curves, the analysis reveals the spatial and temporal characteristics that guide the model’s decision-making. These interpretations provide insight into how specific sensor modalities, representing different anatomical locations and biomechanical movements, contribute to distinguishing healthy gait from pathological gait patterns. The features used in this study include a diverse set of acceleration and gyroscope measurements collected from the head (HE_Acc, HE_FreeAcc, HE_Gyr), lower back (LB_Acc, LB_FreeAcc, LB_Gyr), and bilateral foot sensors (LF_Acc, LF_FreeAcc, LF_Gyr for the left foot; RF_Acc, RF_FreeAcc, RF_Gyr for the right foot). Together, these measurements capture a rich representation of whole-body dynamics during gait.

The first layer of interpretability arises from the IG heatmaps, which illustrate how the model allocates attention to different sensor channels over time for each selected representative sample. Each heatmap contains twelve rows, each corresponding to one of the twelve sensor features, with columns spanning the full temporal sequence of the gait cycle. The color intensities encode the magnitude of the IG attributions, allowing the viewer to identify which sensor–time combinations most influence the model’s prediction. The point of maximum attribution is marked in each heatmap, serving as an indicator of the single most influential sensor reading in the sample. Through these visualizations, it becomes evident that the model’s feature utilization is not uniform across classes; rather, each pathology exhibits its own unique pattern of spatial and temporal emphasis.

For HSs and participants with CIPN, the heatmaps in Figure 8 consistently highlight the lower-back acceleration sensor (LB_Acc). This feature captures the linear acceleration of the trunk, which is a central component of the gait process and highly sensitive to deviations in postural control or stability. In both HS and CIPN samples, LB_Acc displays a pronounced attribution concentration around the mid-stance region of the gait cycle. This similarity may reflect the fundamental importance of trunk dynamics in maintaining balance and gait rhythm, even though CIPN subjects often exhibit subtle alterations due to sensory deficits. Nevertheless, the model successfully captures class-specific signatures, as reflected in the distinct intensity distributions across time. The fact that both groups rely heavily on the LB_Acc sensor suggests that trunk kinematics contain robust diagnostic information for discriminating against normal gait patterns from those affected by neuropathic conditions.

Figure 8.

G-MASA-TCN XAI for Experiment 2 (healthy vs. CIPN) where the red circle with yellow dot is the dominant feature. (a) HS: Integrated Gradients (IG) attribution highlights LB_FreeAcc as the primary feature driving the model’s prediction. The individual-sample IG heatmaps and the global importance panel both show a strong concentration of relevance on LB_Acc and LB_FreeAcc. Temporally, the model places the highest emphasis around frame ~200. (b) CIPN Cohort: For participants with CIPN, IG attribution similarly identifies LB_Acc as the dominant discriminatory feature. The global relevance plot confirms its importance, and the temporal IG distribution again peaks around frame ~200, indicating a consistent temporal sensitivity.

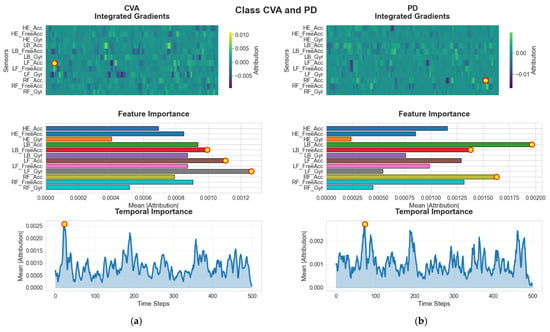

In contrast to the HS and CIPN groups, the SVA and PD (see Figure 9) cohorts show different attribution patterns aligned with their respective biomechanical abnormalities. For individuals with SVA, the model assigns strongest importance to LF_Gyr, the angular velocity of the left foot. This sensor primarily reflects rotational foot movements, which may be particularly relevant for identifying stability-related deviations characteristic of SVA. The IG heatmaps show that LF_Gyr accumulates most of its attribution early in the gait cycle, around frame 10. This finding suggests that the onset of stance or the initial contact phase carries discriminative cues for this population. For subjects with PD, however, the model’s focus shifts toward RF_Acc, the acceleration of the right foot. Parkinsonian gait is known for asymmetries, reduced foot clearance, and irregular acceleration patterns. The concentration of attribution around frame 200 for PD subjects reflects characteristic movement disruptions occurring during the mid-stance or transition phases, when foot stability is challenged. These class-specific patterns demonstrate that the G-MASA-TCN model is attuned to the biomechanical signatures associated with distinct pathologies.

Figure 9.

G-MASA-TCN XAI for Experiment 2 (SVA vs. PD) where the red circle with yellow dot is the dominant feature. (a) SVA Group: IG explanations reveal that LF_Gry is the key feature contributing to classification, as shown by both the sample-level heatmaps and the global feature ranking. The model displays a distinct temporal focus near frame ~10, suggesting early-sequence relevance. (b) For PD Group samples, RF_Acc emerges as the most influential feature. The IG heatmaps and global importance panel consistently highlight this feature, while the temporal relevance pattern reaches its maximum around frame ~200.

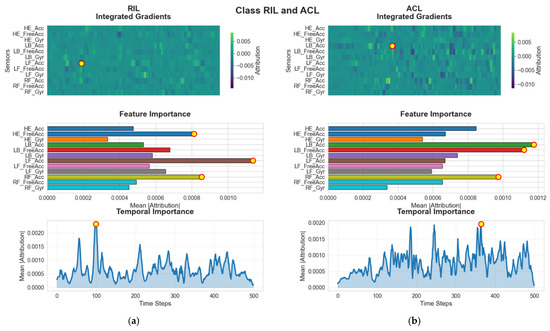

The RIL and ACL groups (See Figure 10) further exhibit unique attribution patterns centered around lower-limb accelerations. For RIL, the model’s attention is most strongly associated with LF_Acc, indicating that the linear acceleration of the left foot serves as a key differentiator for this condition. The temporal peak around frame 100 suggests that mid-stance alterations play a critical role in distinguishing this group. In ACL subjects, however, the dominant feature reverts back to LB_Acc. The attribution for this cohort is delayed relative to others, reaching its highest intensity around frame 380, near the end of the gait cycle. This timing suggests that late-stance and pre-swing phases when the knee undergoes significant load-bearing and extension may contain the strongest indicators of compensation or deficit resulting from ACL.

Figure 10.

G-MASA-TCN XAI for Experiment 2 (RIL vs. ACL) where the red circle with yellow dot is the dominant feature. (a) RIL Group: IG attributions indicate that LF_Acc is the dominant feature across both individual and global analyses. The temporal contribution curve identifies a notable relevance peak at frame ~100, marking this interval as critical for classification. (b) ACL Group: For individuals with ACL injuries, LB_Acc stands out as the leading predictive feature, supported by both sample-level IG visualizations and the global feature ranking. Temporal importance increases sharply around frame ~380, highlighting a late-sequence decision region.

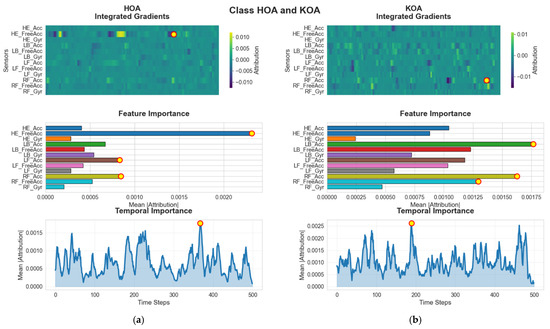

Similarly distinct patterns arise in the HOA and KOA groups (see Figure 11). In HOA samples, the head kinematics specifically HE_FreeAcc (head acceleration minus gravity) are highlighted as the most influential feature. This sensor captures subtle head-movement adjustments associated with discomfort or instability resulting from HOA. The temporal importance peak around frame 220 suggests that the model identifies instability or compensatory adjustments during late mid-stance or early push-off as the key discriminative moment. For KOA subjects, the model again prioritizes RF_Acc, the right-foot acceleration, with its temporal peak around frame 190. KOA commonly influences loading, propulsion, and weight transfer, which explains the reliance on foot acceleration measurements during the mid-gait phases.

Figure 11.

G-MASA-TCN XAI for Experiment 2 (HOA vs. KOA) where the red circle with yellow dot is the dominant feature. (a) HOA Group: The IG results emphasize HE_FreeAcc as the most informative feature for distinguishing HOA samples. The global importance analysis confirms its consistent contribution, and the temporal relevance peaks around frame ~220, indicating a mid-sequence focus. (b) KOA Group: For the KOA cohort, RF_Acc is identified as the principal classification feature, clearly visible in both the IG heatmaps and the global feature importance distribution. The model’s temporal attention is strongest near frame ~190, marking this region as crucial for prediction.

While the IG heatmaps provide sample-level insights, the global feature importance plots aggregate these attributions across time to identify which sensors contribute most consistently across the gait cycle. For each class, the three highest-ranking features reflect the sensors most frequently relied upon by the model. Importantly, the dominant features in the heatmaps always correspond to those with highest mean importance globally. Thus, the importance assigned to LB_Acc in CIPN and ACL, LF_Gyr in SVA, RF_Acc in PD and KOA, LF_Acc in RIL, and HE_FreeAcc in HOA is not limited to single time steps but represents a consistent pattern across the entire gait sequence. These global visualizations help reveal the biomechanical drivers characteristic of each pathology: trunk acceleration for neuropathy-related or ligament injuries, foot angular velocity for balance-related abnormalities, head acceleration for hip-related impairments, and foot acceleration for Parkinsonian and osteoarthritic gait deviations.

The third visualization modality, the temporal importance plot, provides complementary insights by summarizing how the model’s attention evolves across the gait cycle. By averaging attributions across all sensor channels in each time step, the plot identifies critical phases that the model deems most informative. The temporal patterns vary substantially across conditions. HSs and CIPN show their peaks near frame 200, SVA near frame 10, PD again near frame 200, RIL around frame 100, ACL close to frame 380, HOA near frame 220, and KOA around frame 190. These differences emphasize that each pathology manifests discriminative movement signatures at distinct gait phases. By identifying when the model focuses on particular gait events initial contact, mid-stance, push-off, or late-swing, researchers can correlate these moments with clinical gait abnormalities.

Taken together, these three forms of visual explanation offer a rich, multilayered interpretation of the G-MASA-TCN model’s predictions. The IG heatmaps reveal which sensors the model treats as most informative, the global feature importance plots summarize the overall influence of each sensor across time, and the temporal relevance plots pinpoint when in the gait cycle the critical diagnostic information emerges. This integrated analysis enhances understanding of the model’s internal logic, enabling clinicians and researchers to identify not only the anatomical locations most relevant for classification but also the specific phases of movement that contain the strongest biomechanical indicators of pathology. Ultimately, these insights contribute to a more transparent and interpretable gait-classification system, supporting the reliability, clinical credibility, and potential translational application of the model across diverse gait disorders.

4. Discussion

4.1. Result Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate the effectiveness of integrating multi-sensor wearable gait data with advanced temporal deep learning architectures to capture clinically relevant movement signatures across a broad spectrum of neurological and musculoskeletal conditions. By leveraging information from four strategically placed IMUs located on the head, lower back, and both feet, the model was able to exploit both global and segment-specific movement patterns, resulting in highly accurate classification across diverse cohorts. The consistently strong performance across all experimental conditions underscores the richness of wearable inertial data and the suitability of temporal convolutional representations for gait analysis.

A key outcome of this work is the demonstration that gait dynamics, when represented as multi-channel time series, contain sufficiently distinctive patterns to differentiate among multiple pathologies as well as between individuals. The large, clinically annotated dataset used in this study provided a wide range of gait behaviors, including patterns associated with neuropathy, osteoarthritis, ligament injuries, and neurological impairment, alongside healthy control data. The high classification accuracy obtained across repeated cross-validation suggests that these conditions manifest in reproducible sensor-level and temporal signatures. This supports the broader view within the gait analysis community that wearable kinematic data can serve as a reliable proxy for more complex biomechanical measurements traditionally obtained using laboratory motion-capture systems.

Beyond accuracy, the interpretability component of this work provided valuable insights into how different conditions influence movement patterns. The Integrated Gradients analysis revealed that certain sensor channels particularly those associated with lower-back acceleration, foot rotations, and free-acceleration measurements played a dominant role in many classifications. These findings align with established biomechanical understanding: conditions such as neuropathy and osteoarthritis often alter foot–ground interaction forces, trunk stability, and gait symmetry, all of which are reflected in the accelerometer and gyroscope signals captured by wearable IMUs. Temporal attribution further highlighted that specific phases of the gait cycle, such as loading response, mid-stance, or push-off, were more informative for distinguishing pathological gait from normal movement. The convergence of these data-driven insights with clinical expectations strengthens confidence in the relevance and reliability of the extracted gait features. Further, the strong accuracy obtained on real-world gait data highlights the model’s ability to generalize effectively to uncontrolled walking conditions, capturing discriminative subject-specific gait signatures while maintaining robustness across different evaluation protocols.

Another notable result is the model’s ability to identify individuals with high accuracy in the subject-identification experiment. This indicates that gait, when captured at sufficient temporal resolution, functions as a unique biometric signature. Such findings have important implications for personalized healthcare, long-term patient monitoring, and the development of individualized rehabilitation protocols. They also highlight the robustness of the temporal representation learned by the model, which was able to generalize beyond pathology classification to a fundamentally different task requiring fine-grained discrimination.

Overall, the findings advance the field by showing that high-performing, interpretable gait classification is achievable using lightweight wearable sensors and modern deep learning techniques. The integration of explainable AI ensures that predictions are not treated as black-box outputs but are instead grounded in meaningful sensor-level and temporal evidence. This combination of performance, robustness, and transparency positions the proposed framework as a promising tool for future clinical applications, including automated screening, fall-risk assessment, disease progression monitoring, and personalized rehabilitation. Future work may explore real-time deployment, continuous gait tracking in free-living environments, and the use of domain adaptation to enhance applicability across populations and sensor configurations.

4.2. Comparison with the Original MASA-TCN (EEG Emotion Recognition)

Although our gait classification model retains the core structure of the original MASA-TCN proposed in [26] for EEG-based emotion recognition, several adaptations were introduced to better suit the characteristics of inertial gait data. In the original work, the input consisted of relative power spectral density (rPSD) features computed across multiple frequency bands (typically 5–6), resulting in a tensor of the shape , where denotes the number of spectral bands. The SAT layer was designed to operate on a per-channel, per-frequency basis, using a context kernel of the size and stride of to extract band-specific temporal patterns, followed by spatial fusion across electrode channels via a kernel of the size .

In contrast, our implementation processes raw time-domain IMU signals with 36 channels and no explicit frequency decomposition. The SAT context convolution therefore uses a kernel of the size , treating the full set of sensor streams as a single spatial dimension. This modification preserves the spirit of space-aware modeling but reinterprets “space” as anatomical sensor placement rather than spectral content. While the original model supported both continuous emotion regression (using Concordance Correlation Coefficient loss) and discrete classification, our application focuses exclusively on multi-class discrete classification via cross-entropy, necessitating only the mean-pooling classification head.

Activation functions also differ: while the original model used PReLU throughout, ReLU activation followed by batch normalization is applied in the MAAF block, which has shown superior stability when training on raw acceleration and angular velocity signals prone to high variance. The TCN dilation schedule is fixed at in our version, yielding a consistent receptive field across experiments, whereas the original dynamically adjusted dilations starting from the SAT layer’s . Despite these differences, the fundamental contribution—adaptive fusion of multi-scale, spatially informed temporal features—is retained and transferred from brain signals to full-body movement dynamics [26].

4.3. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Gait Classifiers

To contextualize the performance and design of our G-MASA-TCN, it is instructive to compare it with leading deep learning architectures previously applied to IMU-based gait classification. One prominent approach is the DeepConvLSTM framework introduced by Ordóñez and Roggen (2016) [38], which combines four convolutional layers for local feature extraction with two bidirectional LSTM layers to model long-range temporal dependencies. While effective, this hybrid architecture relies on sequential processing in the recurrent component, resulting in higher computational cost and memory usage during inference particularly challenging for real-time clinical applications. Moreover, the LSTM component introduces future context through bidirectionality, violating causality and preventing online deployment.

Another competitive baseline is the attention-augmented TCN-BiGRU model proposed in [40], which stacks dilated temporal convolutional layers with bidirectional GRUs and attention mechanisms. This design achieves a large receptive field of approximately 340 via exponential dilation in the TCN:

This yields strong performance on activity recognition tasks; however, the inclusion of bidirectional recurrence again precludes causal inference, and the parameter count remains high (~1.0 M) due to the recurrent module and attention softmax computations. In contrast, our G-MASA-TCN eliminates recurrence entirely, relying instead on dilated convolutions and multi-scale parallelism to achieve an effective receptive field exceeding 1.2 s, sufficient to encompass multiple gait cycles while maintaining full causality and parallel computation.

More recently, Xiong Wei and Zifan Wan (2024) [39] introduced a TCN-Attention model that augments a temporal convolutional backbone with channel-wise and temporal attention mechanisms to dynamically weigh sensor streams and key timestamps. This approach improves interpretability and adaptability to varying signal quality but introduces additional computational overhead from the attention scoring and softmax operations. Our G-MASA-TCN achieves comparable sensor prioritization implicitly through the learned 1 × 1 fusion weights in the MAAF block and the spatially joint 2D convolutions in SAT layers, without requiring explicit attention modules. This results in a simpler, faster model with fewer hyperparameters.

In terms of parameter efficiency, our model (0.92 M parameters) offers a favorable trade-off between capacity and deployability compared to heavier recurrent hybrids (>1.2 M) and attention-augmented models (~0.8–1.0 M). Crucially, the explicit multi-scale anchor design and built-in spatial fusion provide structured inductive biases tailored to gait kinematics, potentially leading to better generalization across heterogeneous patient populations compared to generic attention or recurrent mechanisms [38,39,40].

Although direct comparison with prior methods on the same dataset is not possible due to the dataset’s recent release (October 2025), the existing literature highlights several limitations of commonly used baseline models for IMU-based gait analysis. Recurrent models such as GRUs often struggle with long-range temporal dependencies and are sensitive to sequence length and noise [38,51]. Transformer-based models, while powerful, typically require large-scale datasets and incur high computational cost, limiting their effectiveness in moderate-sized clinical datasets [52,53]. Similarly, conventional TCNs rely on fixed dilation patterns, which may restrict their ability to capture heterogeneous temporal dynamics across different gait pathologies [45].

In contrast, the proposed G-MASA-TCN integrates multi-scale temporal modeling and adaptive attention mechanisms, enabling robust learning of both short- and long-term gait characteristics across diverse clinical conditions. This architectural design aligns with recent trends in state-of-the-art IMU-based gait analysis [54] while extending them to a more challenging multi-cohort setting.

4.4. Computational Complexity and Power Consumption Analysis

The proposed G-MASA-TCN integrates multi-scale dilated temporal convolutions, channel-wise attention, and residual temporal modeling. While these design choices enhance representational capacity, they may increase computational demand. Therefore, a detailed complexity analysis in terms of Gigaoperations (GOPs) and an estimation of inference-time power consumption are provided to assess practical deployability.

4.4.1. Operation Count (GOP Analysis)

The dominant computational cost of G-MASA-TCN arises from one-dimensional convolutional layers. For a 1D convolution with input channels, , output channels, , the kernel size , and the temporal length , the number of floating-point operations (FLOPs) is approximated as

where the factor of 2 accounts for multiplication and addition. Using the fixed-length input setting adopted in this work (, ), the total complexity per forward pass is summarized as follows:

- SAT layers (multi-scale temporal extraction)

- SAT-1: ; ; : ≈0.007 GOPs.

- SAT-2: ; ; : ≈0.041 GOPs.

- SAT-3: ; ; : ≈0.229 GOPs.

- Attention mechanism

- The channel-attention module consists of a fully connected projection applied after global average pooling. Its computational cost is negligible relative to convolutional layers (<0.001 GOPs).

- Temporal convolution block with residual connection

- TCN-1: ; ; : ≈0.098 GOPs.

- TCN-2: ; ; : ≈0.025 GOPs.

- Residual projection (1 × 1 convolution): ≈0.008 GOPs.

- Fully connected classification head

- The dense layers contribute marginally (<0.001 GOPs). Summing all components, the total computational complexity of G-MASA-TCN is approximately 0.41 GOPs per inference sample for a 5 s gait segment.

4.4.2. Power Consumption Estimation

To estimate inference-time energy consumption, we adopt commonly reported hardware efficiency values. Modern GPUs and embedded AI accelerators typically consume approximately 0.5–1.0 nJ per FLOP, while mobile CPUs require slightly higher energy per operation. Assuming a conservative value of 1 nJ/FLOP, the estimated energy per inference is

This low per-sample energy requirement indicates that G-MASA-TCN is suitable for real-time gait analysis and continuous monitoring scenarios. Importantly, inference is causal and convolution-based, avoiding the quadratic complexity associated with self-attention in Transformer models.

4.4.3. Discussion of Efficiency

Compared with baseline architectures evaluated in this study, G-MASA-TCN exhibits a favorable trade-off between accuracy and efficiency. Transformer-based models typically scale as with sequence length, leading to substantially higher computational and memory costs for long gait sequences. Recurrent architectures such as the GRU require sequential processing, limiting parallelization and increasing latency. In contrast, G-MASA-TCN scales linearly with temporal length () and supports full parallel inference. Despite integrating multi-scale temporal fusion and attention mechanisms, the model remains computationally lightweight, enabling deployment on wearable, edge, or clinical monitoring systems without excessive power consumption.

4.5. Real-Time Inference and Latency Analysis