Abstract

The deep learning paradigm is progressively shifting from non-smooth activation functions, exemplified by ReLU, to smoother alternatives such as GELU and SiLU. This transition is motivated by the fact that non-differentiability introduces challenges for gradient-based optimization, while an expanding body of research demonstrates that smooth activations yield superior convergence, improved generalization, and enhanced training stability. A central challenge, however, is how to systematically transform widely used non-smooth functions into smooth counterparts that preserve their proven representational strengths while improving differentiability and computational efficiency. To address this, we propose a general activation smoothing framework grounded in mollification theory. Leveraging the Epanechnikov kernel, the framework achieves statistical optimality and computational tractability, thereby combining theoretical rigor with practical utility. Within this framework, we introduce Smoothed ReLU (S-ReLU), a novel second-order continuously differentiable (C2) activation derived from ReLU that inherits its favorable properties while mitigating inherent drawbacks. Extensive experiments on CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and ImageNet-1K with Vision Transformers and ConvNeXt consistently demonstrate the superior performance of S-ReLU over existing ReLU variants. Beyond computer vision, large-scale fine-tuning experiments on language models further show that S-ReLU surpasses GELU, underscoring its broad applicability across both vision and language domains and its potential to enhance stability and scalability.

MSC:

68T07

1. Introduction

The expressive capacity and optimization dynamics of artificial neural networks are largely influenced by activation functions, which introduce nonlinearity to transform linear computations into complex representations and capture complex data patterns. Over the past three decades, more than 400 activation functions have been proposed to enhance network performance and efficiency [1]. A clear evolutionary trend has emerged: a shift from nonsmooth activation functions toward more smooth ones. The key reason is that the non-differentiability of nonsmooth functions at certain points presents theoretical challenges for optimization algorithms and constitutes a practical bottleneck limiting performance improvements. In contrast, a growing body of theoretical work shows that smooth activation functions can deliver superior performance [2,3]. Specifically, studies on loss landscape visualization demonstrate that smooth functional curves facilitate the formation of flatter loss landscapes [4], which guide optimizers away from poor local minima, ensure better gradient information propagation [3], and significantly improve training stability. However, most existing smooth functions are exploratory modifications that address nonsmoothness but do not necessarily preserve the proven representational strengths of the original activation functions. Hence, developing a systematic framework for reshaping nonsmooth activation functions holds considerable value for machine learning research.

Our work addresses the three research questions outlined above. We first define a smoothing kernel and apply it to transform a non-smooth activation into a smooth one. After verifying its smoothness and approximation, we analyze its Lipschitz constant and establish the connection between smoothness and gradient stability. To address the third question, we propose S-ReLU as a polished variant of the traditional ReLU. We evaluate its effectiveness on Vision Transformer [5], its related derivatives [6,7], and ConvNeXt [8], across CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100 [9], and ImageNet-1K [10]. The results consistently show that S-ReLU outperforms baseline activation functions. Moreover, fine-tuning experiments on large language models (LLMs) using Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) [11] further demonstrate that S-ReLU surpasses GELU, highlighting its broad applicability in practical scenarios. Compared to heuristic smoothing approaches or sigmoid-based approximations, mollification theory offers a mathematically rigorous framework that guarantees uniform convergence to the original activation function. Crucially, it allows for precise control over the approximation error through the smoothing radius . Furthermore, by selecting compact support kernels like the Epanechnikov kernel, this framework yields activation functions with polynomial closed-form expressions. This avoids the computational overhead of transcendental functions (e.g., exponential or error functions) commonly found in other smooth activations like GELU and SiLU, thereby balancing theoretical optimality with deployment efficiency. The principal contributions of this work are summarized below:

- First, we show that the mollification can smoothly transform non-smooth activation functions while preserving the desirable properties of the original. This ensures that the resulting activation not only inherits the advantages of the base function but also benefits from smoothness.

- Second, we establish that higher degrees of smoothness lead to greater stability of training gradients, and we derive a quantitative relationship between the two. This provides a theoretical foundation for subsequent studies on activation functions.

- Third, we introduce S-ReLU, a new activation function derived from ReLU via mollification. Extensive experiments across architectures, datasets, and tasks demonstrate that S-ReLU consistently outperforms existing activation functions and achieves state-of-the-art performance.

2. Related Work

The study of activation functions has evolved through several stages. Early works introduced compression functions such as Sigmoid and Tanh [12], which bound outputs to a finite interval but often saturate under extreme inputs, leading to gradient vanishing. To address these limitations, non-compression functions were proposed, with the rectified linear unit (ReLU) [13] marking a landmark contribution. By preserving a unit gradient in the positive region and truncating negative activations to zero, ReLU greatly improved optimization stability. However, its asymmetric form results in structural drawbacks: neurons can become permanently inactive (“dying ReLU”), and the absence of negative outputs introduces distributional bias in subsequent layers.

To overcome these issues, a variety of variants were developed. Leaky ReLU [14] introduces a fixed negative slope to maintain gradient flow for sub-zero inputs, while Parameterized ReLU (PReLU) [15] adapts this slope as a learnable parameter. The Exponential Linear Unit (ELU) [16] produces smooth negative outputs that reduce mean-shift effects, and the Continuously Differentiable Exponential Linear Unit (CELU) [17] simplifies the ELU parameterization for easier adjustment. More recently, smoother activations have gained traction for their theoretical and empirical benefits. Swish (SiLU) [18] leverages a smooth and differentiable form to improve gradient propagation and training stability, while Mish [19] combines unbounded positive outputs with moderated negative values, facilitating deeper signal transmission and enhancing generalization.

On the applied side, GELU [20] and its variants have become the dominant activations in large-scale vision and language architectures. They are the default in BERT and RoBERTa [21], used in ViT [5], and widely believed to support successive GPT models [22,23] and recent models like PaLM [24], LLaMA [25], and DeepSeek-V2 [26]. This reliance underscores the role of smooth activations in scaling and stabilizing deep learning. By contrast, a few open-source models, notably Mixtral [27], adopt SiLU, reflecting continued exploration of alternatives.

3. Motivation

Although piecewise linear activations such as ReLU are widely adopted for their simplicity and effectiveness, they suffer from intrinsic drawbacks that hinder further progress in deep neural networks. These include gradient instability arising from non-differentiability [2,28], inefficient information propagation that accelerates signal degradation in deep layers [3], and limited theoretical guarantees for regularization.

Our key idea is to build on the proven representational strengths of established activations and enhance them through systematic smoothing. By introducing smoothness while retaining the core advantages of the original function, we aim to improve differentiability, stability of gradient-based optimization, information propagation across layers, and regularization properties simultaneously. This perspective shifts the focus from designing entirely new exploratory functions to refining and elevating existing well-validated ones. Such an approach promises not only stronger and more stable performance in conventional deep learning tasks, but also provides a principled foundation for advancing modern large-scale architectures, including contemporary vision and language models.

4. Methodology

4.1. Smooth Activation Fuction Is Better

Research by Hayou et al. [3] indicate that the smoothness of an activation function is a key factor influencing the effective propagation of information in deep neural networks. A sufficient condition for an activation function to be smooth is that its second-order derivative can be piecewise represented as a sum of continuous functions. For smooth activation functions, the correlation between inter-layer neuron outputs converges to 1 at a rate of , with the specific formula being , where c represents the correlation, l is the number of network layers, and is a coefficient determined by the target variance q and the activation function f. In contrast, for non-smooth functions like ReLU, this correlation converges at a rate of , with the specific relationship being . This research reveals that in deep networks employing non-smooth activation functions, the correlation of neuron outputs rapidly approaches 1 as the network depth increases. This high degree of correlation impedes the effective propagation of information, leading to unstable gradients and diminished expressive power, ultimately impairing model performance. Intuitively, the non-differentiability of functions like ReLU at the origin acts as a ’kink’ that introduces abrupt changes in the gradient flow. In deep networks, the accumulation of these sharp transitions can rapidly decorrelate the input–output relationship, causing information to degrade as it propagates through layers. Smoother activations, by contrast, offer a continuous transition of derivatives. This preserves the local geometry of the data manifold and ensures that gradients vary more predictably, thereby maintaining stronger signal correlations even in very deep architectures. Therefore, selecting activation functions that meet specific smoothness requirements is an important strategy for enhancing both the training efficiency and the final performance of deep learning models.

4.2. Smoothed Kernel Function

To smooth non-smooth activation functions, we can use the mollification method. This approach involves smoothing the target function by convolving it with a specific kernel. The goal is to create a smooth approximation of the original function without sacrificing its valuable attributes.

Definition 1.

We define the smoothing kernel as follows:

Here, constant A is defined as

Proposition 1.

The smoothing kernel is normalized, i.e., .

Proposition 2.

, i.e., is infinitely differentiable on and . Furthermore, for each natural number k, is bounded on .

Detailed proofs of Propositions 1 and 2 can be found in Appendix A.

Definition 2.

For any we define a family of smoothing kernels generated by scaling the smoothing kernel as follows:

This family of functions has several important properties. Each is normalized, maintaining , and its support is scaled to the interval . As , the family converges to the Dirac delta function in the sense of distributions. We can now employ this framework to smooth the target activation function.

4.3. Smoothness of the Mollified Activation Function

Definition 3.

Let be a locally integrable activation function. The convolution of with the smoothing kernel is called a smoothing of , denoted by or , and defined as:

Remark 1.

It is important to clarify that while the smoothed activation is defined via a convolution integral, this operation is performed analytically during the derivation phase (as shown later in Section 4.6). Consequently, the actual implementation relies on the resulting closed-form polynomial expression, avoiding the need for expensive numerical integration during training or inference. Thus, the convolution-based definition provides theoretical rigor without imposing a runtime computational burden.

Let . Taking partial derivative of it, we can get:

This partial derivative exists for any , because is a function according to Proposition 2. Let be a fixed, arbitrary point. We will consider values of x within a neighborhood of . The function is continuous and has compact support, which implies that it is bounded on the . Let

The support of the integrand with respect to y is the interval . For any x in the chosen neighborhood, this interval is contained in the larger compact set . From Equation (1), we obtain the following bound:

where is the characteristic function of the set K, its specific form is as follows:

Since , it is integrable on the compact set K. This implies that the dominating function is integrable. This argument shows that for any order k, the control conditions required for the differential operator are satisfied. According to the Lebesgue Dominated Convergence Theorem, we can move any order differential operator into the integral sign. Therefore, we can directly calculate the k-th derivative of :

This implies that the k-th derivative of exists for any positive integer k. Let

Since the function is continuous with compact support, it is uniformly continuous on . Consider an arbitrary , we then have

Then we establish a dominating function for the integrand. By the triangle inequality,

Due to the uniform continuity of , when , we have

Thus, we have proven that for any , the derivative is continuous, which implies . This establishes that the mollification process transforms the original activation function into a smooth approximation .

4.4. Approximation Properties of the Mollified Activation Function

While achieving smoothness, a crucial question arises: to what degree does the new function retain the core properties of the original function ? Have we “distorted” the essence of the activation function in pursuit of smoothness? Let us discuss these questions next.

To analyze the approximation error, we start with the term . Since the smoothing kernel integrates to 1, we can rewrite in the following form:

For the term , recall its definition and perform a substitution by letting , which implies . Thus,

According to the triangle inequality for integrals and the fact that :

We consider the activation function that is continuous. Let be an arbitrary compact set. Since , both x and lie within the larger compact set . By the Heine-Cantor Theorem, a function that is continuous on a compact set is also uniformly continuous. Therefore, is uniformly continuous on . By the definition of uniform continuity, for any given at the beginning, there must exist a such that whenever , holds for all . We choose our smoothing parameter to be less than given by uniform continuity, i.e., . In this way, for all in our integral expression, we have . Therefore, for these u, applying the property of uniform continuity yields the following:

Substitute Equation (6) back into our integral:

In summary, we have proven that for any , there exists a such that whenever , then holds for all . From this, we can conclude the uniform convergence of the smoothed activation function to the original activation function on the set D.

By choosing a sufficiently small smoothing parameter , we can make the smoothed activation function approximate the original function arbitrarily accurately. Uniform convergence plays a key role by ensuring that the smoothed activation function maintains the desirable characteristics of the original. It also ensures that the maximum error between the two functions approaches zero over any input interval of interest, thus avoiding unexpected deviations in specific regions.

4.5. Lipschitz Continuity Analysis

In the field of deep learning, an abstract mathematical concept—Lipschitz continuity—is increasingly becoming a key factor in building more reliable, robust, and generalizable neural network models. From theoretical analysis to practical applications, Lipschitz continuity provides a powerful tool for deeply understanding and effectively controlling the behavior of deep networks. Lipschitz continuity offers a stronger condition than standard continuity by constraining a function’s maximum rate of change. To understand this property, we will start with its formal definition.

Definition 4

(Lipschitz Continuous Function [29]). A function with domain is said to be C-Lipschitz continuous with respect to an α-norm for some constant if the following condition holds for all :.

In our analysis, we concentrate on the smallest value of C that satisfies the aforementioned condition. This value is formally defined as the Lipschitz constant. Lipschitz continuity of the activation function is crucial for ensuring well-behaved optimization, thereby promoting efficient convergence during training. Ensuring model stability by controlling the Lipschitz property is an effective way to prevent gradient runaway [30,31,32,33]. The smaller the Lipschitz constant, the more stable the training gradients [29,34].

From the previous derivation, we know that the support set of the smoothing kernel function is . The support set of a function derivative must be contained within the support set of the original function. Therefore, the support set of is also contained in . So we have

For a continuous function , it must be bounded within the closed interval , so we can find a constant that satisfies the condition . Substitute into the above equation and simplify:

Now let us calculate the integral . We know that , by variable substitution :

The value of this integral is completely determined by the kernel function we initially chose. It is a constant that is independent of f, , and x; we denote this constant as . Combining Equations (7) and (8), we can conclude that

This shows that the Lipschitz constant of , , satisfies: . An increase in the value of leads to a broader refinement range for the original activation function, consequently enhancing its overall smoothness. Additionally, increasing the value of lowers the Lipschitz upper bound of the enhanced activation function, thereby promoting a more stable training gradient. Therefore, we can conclude: the higher the smoothness, the higher the training gradient stability, and there is a quantitative relationship between the two, where the specific quantitative relationship is determined by constants M and . This conclusion provides a principled guiding framework for the design of activation functions in the future.

4.6. Reshaping Relu(S-Relu): From Relu to Better

In Section 4.1, we provide evidence that smoother activation functions are advantageous for enhancing both the efficiency of the training process and the final performance of the model. Section 4.3 and Section 4.4 further establish that activation functions constructed via smoothing theory possess desirable smoothness and approximation properties; specifically, they are infinitely differentiable and can approximate the original activation function arbitrarily closely, thereby preserving its favorable characteristics. Building upon these findings, we next apply the proposed methodology to a concrete instance. In particular, we select the widely used ReLU function as the basis for mollification. Regarding the choice of kernel, we strike a balance between theoretical rigor and engineering practicality by adopting the Epanechnikov kernel, which is theoretically optimal for minimizing the Mean Integrated Squared Error. While the Gaussian kernel is a common choice for smoothing, we select the Epanechnikov kernel for two strategic reasons. First, convolving a ReLU with a Gaussian kernel results in expressions involving the Error Function (erf) or exponentials, which are computationally expensive transcendental operations. In contrast, the Epanechnikov kernel is a polynomial; its convolution with ReLU yields a simple piecewise polynomial (S-ReLU), which can be computed using only basic arithmetic operations. Second, the Epanechnikov kernel has a finite support . This ensures that the smoothing effect is strictly local—S-ReLU is exactly linear (preserving ReLU’s properties) outside this interval. Gaussian smoothing, with its infinite support, asymptotically alters the function over the entire domain, theoretically sacrificing the strict linearity and sparsity of the original ReLU.

The standard ReLU activation function computes the maximum of zero and its input, as given by . We select the Epanechnikov kernel function, denoted as , parameterized by the smoothing radius . This kernel acts as a weighting function with compact support on the interval . Its normalized form is:

Applying the preceding theory yields the smoothed activation function S-ReLU:

Remark 2.

While introducing smoothness often incurs a computational premium, the proposed S-ReLU minimizes this overhead through its design. Unlike widely used smooth activations such as GELU [20] or SiLU [18], which rely on computationally expensive transcendental functions, S-ReLU is constructed as a piecewise polynomial function. Within the smoothing interval , it requires only basic arithmetic operations (addition, multiplication) and avoids the latency associated with approximating infinite series. Consequently, S-ReLU maintains a computational efficiency comparable to leaky ReLU variants, making it highly suitable for both large-scale training and latency-sensitive inference scenarios.

Differentiating the S-ReLU function twice yields the following:

This indicates that S-ReLU is an activation function with continuous second derivatives, which meets the definition of a smooth function in Section 4.1. We specifically target second-order differentiability () rather than higher-order or infinite smoothness () for two pragmatic reasons. First, from an optimization perspective, continuity ensures a well-defined and continuous Hessian matrix, which is sufficient to guarantee stability of curvature-based optimization dynamics and avoid abrupt changes in the loss landscape. Second, achieving typically requires kernels with infinite support, which leads to computationally expensive transcendental functions. In contrast, restricting smoothness to allows us to utilize the Epanechnikov kernel, yielding a computationally efficient piecewise polynomial form while still satisfying the rigorous requirements for gradient stability. We use the uniform error metric to quantify how well S-ReLU approximates the target function. The calculation result is given as follows:

This result clearly demonstrates that, compared to ReLU, the approximation error of S-ReLU is controllable and proportional to the smoothing radius . This is a valuable property, as it allows us to precisely control the extent of the approximation error introduced by the smoothing operation by choosing the value of . A detailed proof is provided in Appendix B. Further details regarding S-ReLU are available in the appendices. Specifically, Appendix C presents the Python-style pseudocode, while Appendix D contains a more in-depth discussion of its characteristics. Finally, we discuss Lipschitz continuity. Based on the theory in Section 4.5, we can calculate the Lipschitz constant for each activation function.

Fact 1.

Lipschitz constant of GELU is 1.084; Lipschitz constant of SiLU is 1.100; Lipschitz constant of Mish is 1.089. Lipschitz constant of S-ReLU is 1.000.

Remark 3.

The Lipschitz constants presented in Fact 1 reveal a fundamental structural advantage of S-ReLU. Theoretically, an activation function f with a Lipschitz constant (such as GELU and SiLU) acts as an expansive operator. In deep neural networks, where gradients are computed via the chain rule involving products of layer Jacobians, an expansive activation can cause the gradient magnitude to grow exponentially with depth d (upper bounded by ), potentially leading to gradient explosion or optimization instability. In contrast, S-ReLU guarantees , making it a strictly non-expansive operator. This ensures that the gradient norm is never mathematically amplified by the activation layer itself (). This property provides a quantifiable theoretical guarantee for training stability in deep architectures, distinguishing S-ReLU from existing smooth variants.

The detailed proof can be found in Appendix E. S-ReLU’s Lipschitz constant of 1 ensures that its output never changes more rapidly than its input. This property acts as a vital safeguard for stabilizing gradient flow in the network, which helps prevent the problem of exploding gradients and makes the model more robust to small input perturbations—a clear advantage over other activation functions.

4.7. Theoretical Connection: From Mollification to Optimization

The mathematical properties derived from our mollification framework translate directly into the empirical improvements observed in the subsequent experiments. Specifically, the guarantee of continuity ensures a continuous Hessian matrix, which effectively smooths out the loss landscape. This regularity allows second-order information—often implicitly utilized by adaptive optimizers like Adam—to guide the optimization trajectory more robustly than is possible with the singular Hessian of non-smooth functions. Furthermore, by selecting the normalized Epanechnikov kernel, we mathematically constrain the Lipschitz constant to exactly 1.000. This ensures that S-ReLU acts as a strictly non-expansive operator, thereby preventing the exponential accumulation of gradient magnitudes in deep layers, which serves as a crucial theoretical advantage over expansive activations like GELU or SiLU. Finally, the uniform convergence property guarantees that S-ReLU approximates the representational sparsity of ReLU with a controllable error bound, allowing the model to retain the favorable linear regions of the original function while eliminating the optimization difficulties caused by the non-differentiable singularity at the origin.

5. Experiments

Experimental Setup. We conducted experiments on the CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and ImageNet-1K datasets to evaluate the effectiveness of S-ReLU for image classification, as well as on LLM fine-tuning with human preference datasets SHP [35], HH [36], and GPT-2 [22]. We compare against representative ReLU variants, including GELU, ELU, PReLU, CELU, SiLU, and Mish. Detailed training configurations and hyperparameters are provided in Appendix F. For image classification, we use CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100 [9], and ImageNet-1K [10], which cover small- to large-scale benchmarks with increasing category numbers and image resolutions. For LLM fine-tuning, we adopt the human preference datasets SHP [35] and HH [36], which are widely used for aligning model outputs with human judgments. We also fine-tune GPT-2 (137M parameters); given its moderate size, we perform full parameter fine-tuning rather than LoRA-based tuning. We compare S-ReLU against representative ReLU variants, including GELU [20], ELU [16], PReLU [15], CELU [17], SiLU [18], and Mish [19], as detailed in Section 2 and Section 3. All experiments were conducted on 4 × A100 GPUs using the AdamW optimizer (weight decay 0.05), truncated normal initialization, gradient clipping norm of 1.0, cross-entropy loss, and a cosine annealing learning rate scheduler with linear warmup. For all transformer- and CNN-based architectures, we set (see Section 5.3 for sensitivity analysis). Each experiment was repeated three times, and we report mean and standard deviation. Additional hyperparameter details are provided in Appendix F.

Datasets. In the experiments on image classification tasks, we use three datasets, ranked by the number of categories: CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100 [9], and ImageNet-1K [10]. In the experiments on the Large-Scale Language Model (LLM) fine-tuning task, we use two human preference datasets: SHP [35] and HH [36].

Baselines. We experimentally compared the performance of S-ReLU with several typical ReLU correction methods described in Section 2 and Section 3: GELU [20], ELU [16], PReLU [15], CELU [17], SiLU [18], and Mish [19].

Experimental hyperparameters. For all transformer-based and CNN-based architectures, we directly set to 0.001. See Section 5.3 for sensitivity analysis of parameter delta. Detailed experimental hyperparameters are provided in Appendix F.

5.1. Task of Image Classification

Evaluation of ViTs on CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and ImageNet-1K. To comprehensively evaluate the proposed activation, we conducted experiments on ViT, DeiT and TNT. CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 were selected to examine the sensitivity of activation functions under different data distributions, while ImageNet-1K, with its larger image resolution and broader category coverage, was employed to assess performance in more challenging large-scale scenarios.

As summarized in Table 1, S-ReLU consistently outperforms all existing ReLU variants across every dataset and architecture. The gains are evident on both small-scale benchmarks(CIFAR-10/100), where S-ReLU achieves markedly higher accuracy, and on the large-scale ImageNet-1K dataset, where it surpasses strong baselines under more demanding conditions. These results demonstrate not only the superior fitting ability of S-ReLU, but also its strong generalization capacity, showing that the advantages of smoothing are preserved across data regimes of different scales and complexities.

Table 1.

Test accuracy on CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and ImageNet-1K over 100 epochs.

Evaluation of ConvNeXt on CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100 and ImageNet-1K. Beyond transformer families, we investigate the universality of S-ReLU in convolutional networks by testing it on ConvNeXt, a leading convolutional model designed with modern principles to rival Transformers. This setting provides a stringent test of whether the performance improvements of S-ReLU are tied to specific architectural choices or generalize broadly across models.

Experimental results on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 with 100 training epochs demonstrate that ConvNeXt models equipped with S-ReLU achieve consistently higher classification accuracy than those with existing activation functions. Notably, on the more challenging ImageNet-1K benchmark, S-ReLU continues to surpass GELU, SiLU, Mish, and other baselines, establishing new performance levels for ConvNeXt. These results confirm that the advantages of S-ReLU are not restricted to Transformer-based architectures but extend robustly to convolutional networks as well. Together with our earlier findings on Vision Transformers, these results highlight that S-ReLU delivers both architectural universality and strong generalization ability (Table 2).

Table 2.

Testaccuracy of experiments conducted on ConvNeXt-tiny for 100 epochs.

5.2. Task of Large Language Model (LLM) Fine-Tuning

To test the generalizability of our proposed S-ReLU activation function outside of computer vision, we also evaluated its performance in the increasingly important field of Large Language Models. Specifically, we fine-tune GPT-2 on the SHP and HH datasets using DPO. Importantly, both datasets pose challenges of stability and nuanced representation, making them suitable testbeds for evaluating whether activation functions like S-ReLU can enhance optimization robustness and expressive capacity. Specifically, we employ the standard DPO objective function [11], which optimizes the policy directly from human preferences without explicit reward modeling. The loss function is defined as:

where and denote the preferred and dispreferred completions, respectively, and is the KL-divergence penalty coefficient. Regarding the evaluation metrics reported in Table 3, we define the Implicit Reward for a given input x and output y as . Chosen Reward and Rejected Reward refer to the average implicit rewards assigned to the ground-truth preferred () and dispreferred () responses in the test set. Preference Accuracy is calculated as the percentage of cases where the model assigns a higher implicit reward to the chosen response than to the rejected one. Because DPO relies on a reference strategy that may diverge from the true data distribution, we begin with supervised fine-tuning (SFT) to reduce this gap and then apply DPO with different penalty coefficients .

Table 3.

Metrics comparison between S-RELU and GELU in the task of LLM fine-tuning.

Table 3 reports the mean and standard deviation for each evaluation metric, averaged over several experimental runs. Compared with GELU, S-ReLU consistently achieves higher chosen rewards, lower rejected rewards, larger reward margins, and improved preference accuracy. These results indicate that S-ReLU not only enhances the model’s ability to assign higher utility to preferred responses while penalizing non-preferred ones, but also strengthens its discriminative margin and alignment with human feedback. The consistent performance gains on all metrics confirm that introducing smoothness is an effective strategy, especially since it maintains the representational capabilities of the initial activation function. This demonstrates that the advantages of S-ReLU generalize robustly from vision tasks to LLM preference optimization, thereby confirming its potential as a broadly applicable activation function for deep learning.

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis

In this section, we focus on the impact of different on the final results. We set at 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 5, and 10, and perform experiments on the CIFAR10 and CIFAR100 datasets using ViT-tiny. We perform three runs and report the mean and standard deviation in Table 4.

Table 4.

Test accuracy of ViT on CIFAR-10 with different sensitivity parameters for 100 epochs.

The sensitivity analysis presented reveals that S-ReLU achieves peak performance at across both CIFAR-10 () and CIFAR-100 (), with performance remaining remarkably robust within the magnitude range of to . While increasing beyond causes a theoretically consistent drop in accuracy due to excessive smoothing of the rectified non-linearity essential for feature representation, the stability observed in the lower range confirms that S-ReLU is not hypersensitive to hyperparameter perturbations. Consequently, the consistent optimality of across datasets of varying complexity establishes it as a reliable universal default, thereby eliminating the need for extensive grid search and significantly enhancing the practical usability of the activation function for real-world deployments.

5.4. Empirical Verification of Gradient Stability

In Section 4.5, we theoretically derived that the Lipschitz constant of S-ReLU is inversely proportional to the smoothing parameter , specifically bounded by . This theoretical insight implies that increasing the smoothing radius should mathematically constrain the maximum rate of change of the activation function, thereby suppressing the magnitude of gradients during backpropagation. To empirically validate this property and quantify the relationship between smoothness and optimization stability, we monitored the average global Gradient Norm of the ViT model trained on CIFAR-10 over 100 epochs under varying configurations, with the detailed results reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Test gradient norm of ViT on CIFAR-10 with different sensitivity parameters for 100 epochs.

The experimental data demonstrates a strict inverse correlation between the smoothing parameter and the gradient norm, providing strong empirical corroboration for our theoretical analysis. Specifically, at a small smoothing radius of , the gradient norm remains relatively high at , exhibiting behavior similar to the standard ReLU which permits sharper gradient updates; however, as increases to and beyond, the gradient norm decreases monotonically, dropping to at and further to at . These findings confirm that effectively acts as a control knob for optimization dynamics, where a larger enforces a tighter Lipschitz constraint to suppress gradient magnitudes and promote stability, whereas a smaller allows for more aggressive updates akin to non-smooth activations.

5.5. Computational Efficiency Analysis

To evaluate the practical deployment efficiency of S-ReLU relative to standard baselines, we conducted a rigorous micro-benchmark. We measured the average execution time for forward and backward passes, as well as the peak memory footprint with the detailed results summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Test Computational Efficiency of ViT on CIFAR-10 for 100 epochs.

The benchmarking results highlight that S-ReLU achieves a highly competitive computational profile, demonstrating superior or comparable efficiency to existing state-of-the-art activations. Specifically, in the forward pass, S-ReLU (55.2 ms) outperforms widely used functions such as GELU (59.2 ms), ELU (57.7 ms), and PReLU (57.5 ms); this efficiency gain is primarily attributed to S-ReLU’s piecewise polynomial formulation, which avoids the latency associated with computationally expensive transcendental operations. Furthermore, in terms of backward propagation and memory usage, S-ReLU maintains performance parity with efficient baselines like SiLU and CELU while avoiding the significant computational overhead observed in PReLU (which requires 189.5 ms for the backward pass), thereby confirming that the proposed smoothing framework incurs negligible additional cost and is well-suited for high-throughput practical applications.

6. Discussion

Developing effective activation functions has long been a central problem in machine learning. While non-smooth activations suffer from well-documented limitations, smooth activations have emerged as a promising direction. Yet, a general methodology for systematically smoothing non-smooth activations remains absent. In this work, we introduce a mathematically rigorous and practically effective framework based on mollification theory to smooth non-smooth activations while preserving their desirable properties. Within this framework, we establish a quantitative relationship between smoothness and gradient stability, offering a theoretical foundation for advancing activation function design. Building on this, we derive a new activation function, S-ReLU, as a polished variant of ReLU. Across image classification and LLM fine-tuning tasks, S-ReLU consistently outperforms existing rectified ReLU variants. Our findings position S-ReLU as a strong new member of the family of high-performance activation functions, while also opening avenues for future research on smooth and stable architectures.

Limitations and Future Work

The results point to both theoretical and practical opportunities for advancing activation research. First, we employed the Epanechnikov kernel as the smoothing kernel due to its strong theoretical characterization, but alternative choices may yield improvements. In particular, shifting kernel design from fixed theoretical selection to dynamic, data-driven, or learnable formulations could provide greater flexibility and performance. Second, the applicability of mollification to other architectures, such as Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks (KANs), remains an open question. Third, although this work establishes the link between smoothness and gradient stability and analyzes the Lipschitz constant, deeper theoretical investigations are needed to understand the impact of smoothing on representational capacity, generalization bounds, and convergence. Fourth, beyond fixed or learnable parameterizations, the temporal scheduling of the smoothing parameter offers a promising direction. Similarly to learning rate annealing, a dynamic strategy—starting with a larger to ensure a convex, easy-to-optimize landscape during the early training phase, and gradually annealing it towards zero to recover the sparsity and efficiency of ReLU—could potentially combine the optimization benefits of smoothing with the representational sparsity of the original function. We plan to investigate such scheduling strategies in future work. Then, while S-ReLU demonstrates strong empirical results in image classification and large-scale language model fine-tuning, its extension to broader domains holds promise for advancing future studies. Finally, while this study validates S-ReLU across the currently dominant backbones—including CNNs, Vision Transformers, and LLMs—we acknowledge that the landscape of deep learning is vast. Future work could extend the evaluation of S-ReLU to other specialized architectures, such as Diffusion Models for generative tasks or RNNs for time-series forecasting, to further verify its universality.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/math14010072/s1, File S1: Mollification-code.

Author Contributions

Methodology, W.Z.; Software, Y.Z. (Yuxin Zheng); Validation, W.Z.; Resources, W.Z. and Y.Z. (Yutong Zhang); Writing—original draft, W.Z. and W.M.; Supervision, Y.Z. (Yutong Zhang) and W.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the efforts made by the reviewers and editorial team for our article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Proof of Propositions 1 and 2

Proof of Proposition 1.

The Smoothing Kernel has normalization

□

Proof of Proposition 2.

For , In this interval, . Any derivative of the constant function is 0, so is in this interval.

For , is an elementary function and naturally has derivatives of any order.

For , since is an even function, we only need to consider case where . According to the definition, for , so all right-sided derivatives are 0. Our task is to prove that all left-sided derivatives are also 0. We use mathematical induction to prove that the proposition holds for all .

For , obviously valid. Assume that holds for some . For takes the form: , where is a polynomial with x and as variables, i.e., a rational function. We need to prove that holds, i.e., . According to the definition of derivatives

Since and for , the right limit is obviously 0. We only need to calculate the left limit:

Therefore , holds true. According to mathematical induction, for all . Similarly, this also holds at . In summary, , and show that is infinitely differentiable over the entire . □

Lemma A1 (Extreme Value Theorem).

A continuous function defined on a compact set must be bounded and can reach its maximum and minimum values.

From the lemma, we know that there exists a constant such that for all , we have . And for all . Therefore, for any , we have .

Appendix B. Proofs Related to S-ReLU

First, prove the expression for S-ReLU.

- (1)

- When , at this point, the right boundary of the integration window satisfies . This implies that the entire integration interval falls within the range . Within this interval, . Therefore, the integral is:

- (2)

- When , at this point, the left boundary of the integration window satisfies . This means the entire integration interval [, ] lies within the range where . Within this interval, . The integral is:

- (3)

- When , at this point, the integration interval spans the origin. According to our previous analysis, the lower limit of integration is , and the upper limit is . The integral is:

Therefore, the expression for S-ReLU is

Next, we will calculate the uniform error. When or : In these two intervals, the definition of is identical to that of ReLU(x), so the error is 0. When , the error function is given by

This function is monotonically decreasing on , so its minimum value is . Similarly, the same result holds for the interval , so the uniform error is .

Appendix C. Smoothed ReLU(S-ReLU) Pseudocode

| Algorithm A1 Smoothed ReLU(S-ReLU) Pseudocode |

| import torch |

| import torch.nn as nn |

| import torch.nn.functional as F |

| class SReLU(nn.Module): |

| def __init__(self, trainable=False): |

| super().__init__() |

| super(SReLU, self).__init__() |

| def forward(self, x): |

| a = 0.01 |

| condition1 = (x <= -a) |

| condition2 = (x > -a) & (x < a) |

| condition3 = (x >= a) |

| p1 = torch.zeros_like(x) |

| p2 = (x/2.0 + 3.0*x**2/(8.0*a) + 3.0*a/16.0 - x**4/(16.0*a**3)) |

| p3 = x |

| output = torch.where(condition1, p1,torch.where(condition2, |

| p2,p3)) |

| return output |

Appendix D. Further Discussion on Properties of S-ReLU

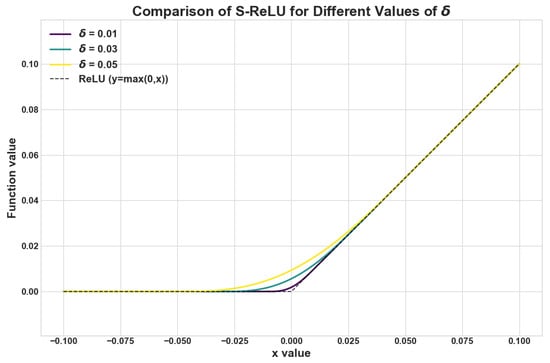

Figure A1 shows S-ReLU images obtained for different values of . When approaches 0, the function becomes the ReLU. As shown in the figure, the S-ReLU is smooth and differentiable everywhere, completely eliminating the non-differentiability of the ReLU at the origin, which is crucial for gradient-based optimization algorithms. Smooth activation functions produce smoother loss landscapes, theoretically helping to accelerate the optimization process and find better solutions. Within the interval , the S-ReLU function value varies, while its gradient persists and is non-zero. This directly addresses the drawback of the standard ReLU, where the gradient is always zero on the negative half-axis, effectively avoiding the “dead ReLU problem”—a phenomenon in which neurons permanently stop learning due to improper weight updates. The parameter , as an adjustable hyperparameter, allows precise control of the degree of smoothing based on specific task requirements.

Figure A1.

S-ReLU with different value.

Appendix E. Proof of Lipschitz Continuity Analysis

Remark A1.

Lipschitz constant of GELU is 1.084.

Proof.

To establish the Lipschitz continuity of the GELU activation function, we first analyze its derivative to find its upper bound. The first derivative of GELU(x) is defined as:

where is the cumulative distribution function and is the probability density function of the standard normal distribution. To find the maximum value of this derivative, we utilize the second derivative test. The second derivative is calculated as:

The extrema of the first derivative occur where the second derivative equals zero. Setting , we solve for x:

Since the exponential term is always positive, the expression is zero only when . This yields the critical points . By evaluating the first derivative at these critical points, we can determine its maximum value. For , we find:

This value represents the maximum slope of the GELU function. Since the derivative is bounded by this value, we confirm that GELU is Lipschitz continuous with a Lipschitz constant of approximately 1.084. □

Remark A2.

Lipschitz constant of SiLU is 1.100.

Proof.

To establish the Lipschitz continuity of the SiLU (Sigmoid Linear Unit) function, we first analyze its derivative to find its upper bound. The SiLU function is defined as:

The Lipschitz constant is the maximum absolute value of its derivative, . To find this maximum, we employ the second derivative test. The first and second derivatives are:

The extrema of the first derivative occur where the second derivative equals zero. Setting , we solve for the critical points, which are found to be . By evaluating the first derivative at these critical points and analyzing its behavior, we find that its value is bounded within the interval . The Lipschitz constant is the supremum of the derivative’s absolute value. Therefore, we conclude that the Lipschitz constant for SiLU is approximately . □

Remark A3.

Lipschitz constant of Mish is 1.089.

Proof.

To determine the Lipschitz constant for the Mish activation function, we perform an analysis of its derivatives. The objective is to find the supremum of the absolute value of the first derivative, which requires locating its global extrema. The Mish function is defined by the expression:

The extrema of its first derivative are found by identifying the roots of the second derivative. The first and second derivatives are as follows:

By setting the second derivative to zero, we solve for the critical points of the first derivative. This calculation yields two approximate solutions: and . Evaluating the first derivative at these critical points and analyzing its global behavior reveals that its values are bounded within the interval . Therefore, the Lipschitz constant for the Mish function, which is the maximum absolute value of its derivative, is established to be . □

Remark A4.

Lipschitz constant of S-ReLU is 1.000.

Proof.

We know that the expression for SiLU:

Calculating the first derivative yields:

Calculating the second derivative yields:

We already know that on the interval , , and on the interval , . Now we need to analyze the extrema of the derivative on the interval . Let . We find its critical points by taking the derivative of :

Setting to find the fixed point yields . The fixed point lies on the boundary of the interval. This indicates that within the interval , is monotonic. For any , we have . Therefore, . Thus, calculating the derivative at the endpoint yields:

Therefore, the derivative of S-ReLU is bounded within the interval . Therefore, S-ReLU’s Lipschitz constant is 1.000. □

Appendix F. Details of Experimental Settings

In this appendix, we provide implementation details and hyperparameter settings to facilitate reproducibility. The main datasets and baseline methods are introduced in the main text (Section 5). Here we report additional training configurations specific to each model and dataset. Hyperparameter sensitivity to is reported in Section 5.3; according to the experimental results, we use for all experiments.

Image classification. For CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100, we trained ViT-Tiny, DeiT-Tiny, and TNT-Small for 100 epochs. All models used AdamW with weight decay of 0.05, cosine annealing learning rate scheduling (initial learning rate , minimum , with 20 warmup epochs starting from ), and gradient clipping of 1.0. Training was performed with a batch size of 256, cross-entropy loss, and layer normalization, without dropout or drop path. For CIFAR tasks, images of size were divided into patches of size 4, with embedding dimensions of 192 for ViT-Tiny and DeiT-Tiny and 384 for TNT-Small. Standard data augmentations provided by timm were applied.

For ImageNet-1K, we trained ViT-Tiny and DeiT-Tiny for 100 epochs under largely similar optimization settings. Images were resized to , patch size was set to 16, and the embedding dimension was 192. The same AdamW optimizer, learning rate schedule, batch size (256), loss function, and normalization strategy were adopted, with no dropout or drop path used.

LLM fine-tuning. For SHP, HH, and GPT-2 fine-tuning tasks, we adopted full-parameter fine-tuning. All experiments were conducted on 4 × A100 GPUs, and each experiment was repeated three times, with mean and standard deviation reported.

References

- Kunc, V.; Kléma, J. Three decades of activations: A comprehensive survey of 400 activation functions for neural networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.09092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, K.; Kumar, S.; Banerjee, S.; Pandey, A.K. Smooth maximum unit: Smooth activation function for deep networks using smoothing maximum technique. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 794–803. [Google Scholar]

- Hayou, S.; Doucet, A.; Rousseau, J. On the impact of the activation function on deep neural networks training. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 2672–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Xu, Z.; Taylor, G.; Studer, C.; Goldstein, T. Visualizing the loss landscape of neural nets. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2018, 31, 6391–6401. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16 × 16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Online, 26–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Xiao, A.; Wu, E.; Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y. Transformer in transformer. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 15908–15919. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Cord, M.; Douze, M.; Massa, F.; Sablayrolles, A.; Jégou, H. Training data-efficient image transformers & distillation through attention. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 10347–10357. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.Y.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A convnet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 11976–11986. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Hinton, G. Learning Multiple Layers of Features from Tiny Images; Technical Report; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Rafailov, R.; Sharma, A.; Mitchell, E.; Manning, C.D.; Ermon, S.; Finn, C. Direct preference optimization: Your language model is secretly a reward model. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 53728–53741. [Google Scholar]

- Hornik, K. Approximation capabilities of multilayer feedforward networks. Neural Netw. 1991, 4, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, V.; Hinton, G.E. Rectified linear units improve restricted boltzmann machines. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-10), Haifa, Israel, 21–24 June 2010; pp. 807–814. [Google Scholar]

- Maas, A.L.; Hannun, A.Y.; Ng, A.Y. Rectifier nonlinearities improve neural network acoustic models. In Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on International Conference on Machine Learning, Atlanta, GA, USA, 16–21 June 2013; Volume 30, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Delving deep into rectifiers: Surpassing human-level performance on imagenet classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 13–16 December 2015; pp. 1026–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Clevert, D.A.; Unterthiner, T.; Hochreiter, S. Fast and accurate deep network learning by exponential linear units (elus). arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.07289. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, J.T. Continuously differentiable exponential linear units. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.07483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, P.; Zoph, B.; Le, Q.V. Searching for activation functions. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.05941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, D. Mish: A self regularized non-monotonic activation function. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.08681. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrycks, D.; Gimpel, K. Gaussian error linear units (gelus). arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.08415. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; Volume 1, pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI Blog 2019, 1, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhery, A.; Narang, S.; Devlin, J.; Bosma, M.; Mishra, G.; Roberts, A.; Barham, P.; Chung, H.W.; Sutton, C.; Gehrmann, S.; et al. Palm: Scaling language modeling with pathways. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2023, 24, 1–113. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.13971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Feng, B.; Wang, B.; Wang, B.; Liu, B.; Zhao, C.; Dengr, C.; Ruan, C.; Dai, D.; Guo, D.; et al. Deepseek-v2: A strong, economical, and efficient mixture-of-experts language model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.04434. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, A.Q.; Sablayrolles, A.; Roux, A.; Mensch, A.; Savary, B.; Bamford, C.; Chaplot, D.S.; Casas, D.d.L.; Hanna, E.B.; Bressand, F.; et al. Mixtral of experts. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.04088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. Mathematical analysis and performance evaluation of the gelu activation function in deep learning. J. Math. 2023, 2023, 4229924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khromov, G.; Singh, S.P. Some Fundamental Aspects about Lipschitz Continuity of Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Erichson, N.B.; Azencot, O.; Queiruga, A.; Hodgkinson, L.; Mahoney, M.W. Lipschitz Recurrent Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, New Orleans, LO, USA, 6–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fazlyab, M.; Robey, A.; Hassani, H.; Morari, M.; Pappas, G.J. Efficient and accurate estimation of lipschitz constants for deep neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamba, M.; Azizpour, H.; Björkman, M. On the lipschitz constant of deep networks and double descent. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.12309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, F.; Rolland, P.; Cevher, V. Lipschitz constant estimation of Neural Networks via sparse polynomial optimization. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.08688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Liang, J.; Song, Y.; Yu, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, W.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Lipschitz generative adversarial nets. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 7584–7593. [Google Scholar]

- Ethayarajh, K.; Choi, Y.; Swayamdipta, S. Understanding dataset difficulty with V -usable information. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–23 July 2022; pp. 5988–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Jones, A.; Ndousse, K.; Askell, A.; Chen, A.; DasSarma, N.; Drain, D.; Fort, S.; Ganguli, D.; Henighan, T.; et al. Training a helpful and harmless assistant with reinforcement learning from human feedback. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.05862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.