Abstract

The celebrated question of whether continues to define the boundary between the feasible and the intractable in computer science. In this paper, we revisit the problem from two complementary angles: Time-Relative Description Complexity and automated discovery, adopting an epistemic rather than ontological perspective. Even if polynomial-time algorithms for NP-complete problems do exist, their minimal descriptions may have very high Kolmogorov complexity. This creates what we call an epistemic barrier, making such algorithms effectively undiscoverable by unaided human reasoning. A series of structural results—relativization, Natural Proofs, and the Probabilistically Checkable Proofs (PCPs) theorem—already indicate that classical proof techniques are unlikely to resolve the question, which motivates a more pragmatic shift in emphasis. We therefore ask a different, more practical question: what can systematic computational search achieve within these limits? We propose a certificate-first workflow for algorithmic discovery, in which candidate algorithms are considered scientifically credible only when accompanied by machine-checkable evidence. Examples include Deletion/Resolution Asymmetric Tautology (DRAT)/Flexible RAT (FRAT) proof logs for SAT, Linear Programming (LP)/Semidefinite Programming (SDP) dual bounds for optimization, and other forms of independently verifiable certificates. Within this framework, high-capacity search and learning systems can explore algorithmic spaces far beyond manual (human) design, yet still produce artifacts that are auditable and reproducible. Empirical motivation comes from large language models and other scalable learning systems, where increasing capacity often yields new emergent behaviors even though internal representations remain opaque. This paper is best described as a position and expository essay that synthesizes insights from complexity theory, Kolmogorov complexity, and automated algorithm discovery, using Time-Relative Description Complexity as an organising lens and outlining a pragmatic research direction grounded in verifiable computation. We argue for a shift in emphasis from the elusive search for polynomial-time solutions to the constructive pursuit of high-performance heuristics and approximation methods grounded in verifiable evidence. The overarching message is that capacity plus certification offers a principled path toward better algorithms and clearer scientific limits without presuming a final resolution of .

Keywords:

P ≟ NP; NP-completeness; Kolmogorov complexity; automated algorithm discovery; approximation algorithms; certificate-first verification; Natural Proofs barrier; PCP theorem; exponential time hypothesis (ETH); human-discoverable algorithms MSC:

68Q15; 68Q19

1. Introduction

- Classical context.

Foundational work by Cook and Karp established the framework of NP–completeness that continues to guide how we think about computational difficulty [1,2,3,4]. Many canonical problems, such as the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) (a list of abbreviations is presented at the end of the paper), remain intractable in practice. After decades of research, no polynomial-time algorithm has been found for any NP–complete problem. This persistent absence of progress is not in itself proof that , but it underscores the depth of the challenge. Several well-known theoretical barriers further explain why standard techniques are unlikely to succeed. Relativization showed that many proof strategies behave identically in oracle worlds where and where [5]. The Natural Proofs framework revealed why many combinatorial approaches cannot establish strong lower bounds under reasonable cryptographic assumptions [6]. Algebrization extended these obstacles to a broader range of algebraic techniques [7]. In parallel, the Probabilistically Checkable Proofs (PCPs) theorem, and its refinements, account for the widespread hardness of approximation [8,9,10]. Taken together, these results suggest that any eventual resolution of will require new ideas beyond our current theoretical toolkit.

This article is written for computer scientists and researchers who are familiar with basic notions such as polynomial time, , and NP-completeness, but who may not be specialists in structural complexity theory. We therefore pair formal statements with brief intuitive explanations and explicit references, so that non-experts in complexity can follow the main narrative without needing every technical detail on first reading.

- Relevance and current state of research.

Although the formal question of whether remains open, its implications reach far beyond theory. Intractability limits what can be achieved in optimization, planning, verification, and even in modern machine learning. Because proving complexity separations has proved so difficult, current research often focuses instead on understanding what progress is still possible within these limits. Fine-grained complexity sharpens running-time lower bounds within P via exponent-preserving reductions (for running time, up to factors), typically under SETH/ETH, APSP, or 3SUM-type conjectures [11,12,13]. Parameterised complexity exploits hidden structure to make specific instances more tractable. Approximation algorithms and heuristics aim for the best achievable performance under hardness assumptions. Meanwhile, large-scale search and learning systems have begun to discover effective algorithms automatically. This raises a new challenge: such systems often produce results that are powerful but opaque. This shift motivates a complementary question: How can computational discovery proceed responsibly when interpretability and provability are limited?

- Motivation and purpose.

The rise in high-capacity search and learning systems has created new opportunities to explore very large algorithmic spaces that were once inaccessible. Massive computational power, combined with formal verification and proof logging, makes it possible to search systematically for heuristics, approximation algorithms, and exponential-time improvements. Even if the theoretical question of cannot yet be settled, this technological context allows us to revisit how discovery itself might be organised and validated. Our goal is to propose a framework that encourages such exploration while maintaining scientific accountability.

- Aim and contributions.

This paper offers a methodological framework for algorithmic discovery under persistent theoretical uncertainty. Its main contributions are as follows:

- It introduces a time-relative notion of description complexity, . This complexity measure helps explain why efficient but high–description–complexity algorithms may fall outside human design priors.

- It proposes a pragmatic certificate–first discovery protocol, in which machine-generated algorithms or heuristics are regarded as valid only when accompanied by independent, machine-checkable evidence.

- It connects modern discovery paradigms—from superoptimization to neuro–symbolic program search—to long-standing complexity-theoretic limits such as relativization and Natural Proofs.

- It presents concise case studies showing how certificate-based discovery can produce auditable and reproducible artifacts, even when their internal logic is not easily interpretable.

Together, these elements form a unifying capacity + certificates framework for exploring algorithmic frontiers while ensuring that claims remain verifiable.

This paper does not attempt to resolve . Instead, it makes two complementary claims. First, the discoverability asymmetry: even if efficient algorithms for NP-complete problems exist, their shortest descriptions may be large (high-K). This high complexity forms an ’epistemic barrier’ (see Section 3.5) placing them beyond what humans are likely to design unaided. Second, the pragmatism of automated discovery: with modern computational resources, we can systematically search rich program spaces for promising heuristics. We must require that all such discoveries be accompanied by machine-checkable certificates of correctness or quality.

We formalize a Time-Relative Description Complexity for decision, search, and optimization problems (Section 2), use it to frame the high–K hypothesis (Section 2.4), and outline a certificate-first discovery protocol (Section 4). Empirical context is provided through examples from large language models (Section 4.6), followed by concise case studies (Section 5). The paper concludes with implications for and a summary of the main ideas (Section 6 and Section 7).

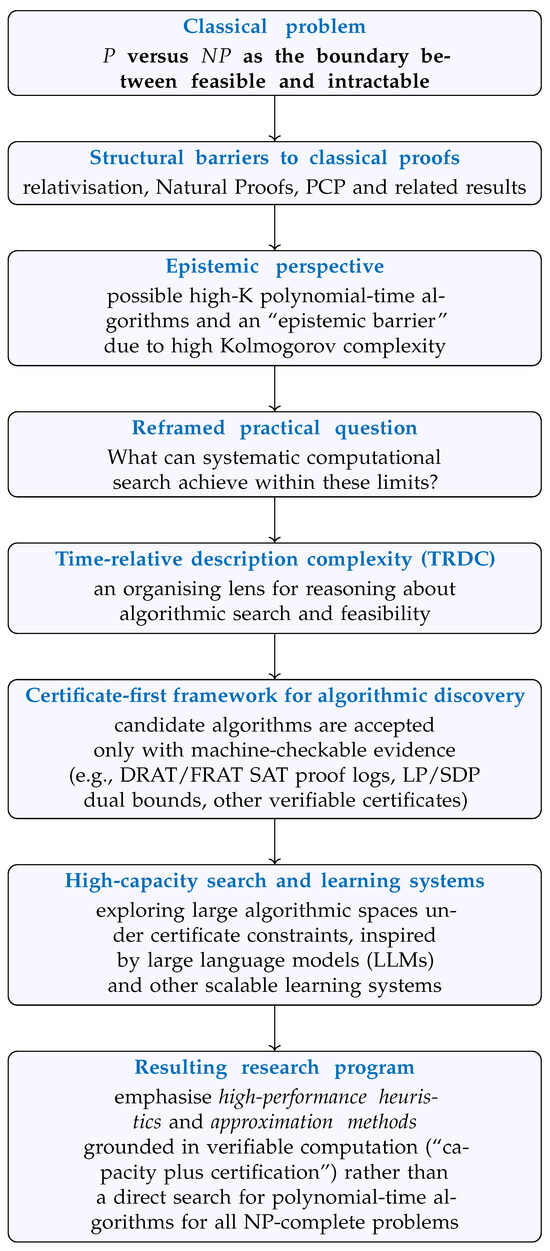

In order to make the structure of our argument explicit, Figure 1 summarizes the conceptual workflow of the paper. We begin from the classical formulation of and the known structural barriers to resolving it, then introduce an epistemic perspective based on Kolmogorov complexity and Time-Relative Description Complexity (TRDC). This motivates a reframed, practice-oriented question about what systematic computational search can achieve, leading to our certificate-first framework for algorithmic discovery and, finally, to the proposed research program centered on “capacity plus certification” as a pragmatic way to push the frontier of feasible computation without presupposing a resolution of .

Figure 1.

Conceptual workflow of the paper. The argument proceeds from the classical P versus question and known structural barriers, through an epistemic perspective based on Time-Relative Description Complexity (TRDC), to a certificate-first framework for algorithmic discovery and a research program centered on “capacity plus certification”.

- Relation to prior work.

Our perspective builds on, and connects, several existing strands of research rather than introducing a new technical formalism in isolation. On the complexity-theoretic side, we rely on classical barrier results for separating P and , including relativisation [5], the Natural Proofs framework [6], and algebrisation [7], as well as PCP-based hardness of approximation [8,9,10]. Our use of description length ideas draws on the theory of Kolmogorov complexity and the related Minimum Description Length (MDL) principles [14,15]. The certificate-first viewpoint is informed by work on verifiable computation and proof logging in SAT and optimization, where large-scale solving is coupled to machine-checkable artifacts such as DRAT/FRAT proof traces and LP/SDP-based bounds [16,17,18]. Finally, our discussion of high-capacity search and learning systems as tools for exploring algorithmic spaces is motivated by recent advances in learning-guided and neuro-symbolic program discovery, including reinforcement-learning and large-model approaches to algorithm design and synthesis [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. To the best of our knowledge, however, these ingredients have not previously been combined into an explicitly epistemic account of P versus based on Time-Relative Description Complexity, nor into a unified “capacity plus certification” research agenda that treats high-capacity search and learning systems as tools for exploring algorithmic spaces under verifiable constraints.

- Terminology

Throughout the paper, we use the phrase certificate-first to describe a discovery workflow in which candidate algorithms or heuristics are considered scientifically valid only when accompanied by machine-checkable evidence of correctness or quality. Examples include DRAT/FRAT (Deletion/Resolution Asymmetric Tautology (DRAT)/Flexible RAT (FRAT)) logs for SAT, LP/SDP dual solutions for optimization, or explicit approximation ratios. In short, discovery may be opaque or high-K (high Kolmogorov complexity), but acceptance requires that results be independently and efficiently verifiable. Readers are asked to note that, while the classical definition uses “certificate” for witnesses to YES-instances of decision problems, our usage is deliberately broader. In this paper, the certificate-first workflow applies equally to decision, search, and optimization problems. Here, a “certificate” is any efficiently (polynomial-time) checkable artifact that attests to feasibility, objective value, or approximation quality (for example, proof logs, dual bounds, or explicit approximation guarantees).

2. Background

- Algorithmic landscapes.

For parameterised algorithms and exact exponential techniques, see [27,28]. For a broad overview of computability and complexity notions relevant here, see [29]. This section briefly reviews the complexity-theoretic notions used in the rest of the paper. We recall the standard classes P, , NP-complete, and NP-hard, the role of Karp reductions, and the main structural results that shape expectations about . We then introduce the Kolmogorov-motivated description measures and Time-Relative Description Complexity (TRDC) that underpin our later high-K heuristic. This sets the stage for a discussion of human cognitive limits and algorithmic discoverability.

2.1. Complexity Classes: NP, NP-Completeness, and NP-Hardness

For readers who do not work daily in complexity theory, the purpose of this section is to recall standard notions (decision problems, running time, , NP-completeness, NP-hardness) and to introduce the Kolmogorov-style description measures that we rely on later in the paper. We signpost the main ideas and keep the technical development lightweight, referring to standard texts for an exposition when appropriate.

The study of computational complexity involves classifying problems based on their inherent difficulty and the resources (time and memory) required to solve (optimally, in the case of NP-hard problems) or verify them. This section focuses on the class , which consists of decision problems where solutions can be verified in polynomial time, and explores NP-completeness and NP-hardness, which formalize the notions of the most challenging problems within and beyond. These classifications form the foundation for understanding the question and the complexity landscape of many practical and theoretical problems.

2.1.1. Decision Problems and the Class NP

Informally, a decision problem is a computational problem where the answer is either “yes” or “no.” For example:

- Given a Boolean formula, is there an assignment of truth values that satisfies it?

- Given a weighted graph G, does there exist a Hamiltonian cycle of weight k or less in G?

- Given a graph G, does there exist a clique of size k or more in G?

Formally, fix a binary encoding of instances. A decision problem is a function

We write for the bit-length of the instance x.

Problem Instances and Running Time

Fix a binary encoding of instances; let denote the bit length of a problem instance x. An algorithm runs in polynomial time if its number of steps is for some constant k.

Definition 1

(The Class P). A decision problem belongs to the class P if there exists a deterministic algorithm that, for every input instance x, outputs the correct / answer in time polynomial in .

Definition 2

(Class (via verification)). A decision problem belongs to if there exist: (i) a polynomial and (ii) a deterministic Boolean verifier that runs in time polynomial in , such that the following holds for every instance x:

- If the correct answer on x is , then there exists a certificate (witness) y with for which accepts.

- If the correct answer on x is , then for all strings y with , returns .

Equivalently, consists of problems decidable by a nondeterministic algorithm that halts in polynomial time on every branch and accepts an input if there exists at least one accepting branch. Intuitively, the machine “guesses” a short certificate y and then performs the same polynomial time check as . The verifier and nondeterministic definitions coincide; see, e.g., [4] (Ch. 7).

Thus, for problems in , a short certificate, when it exists, can be checked quickly (in polynomial time).

Example 1

(SAT). An instance x is a Boolean formula. A certificate y is an assignment to its variables. The verifier evaluates the formula under y and returns YES iff the formula is true. V runs in time polynomial in (and in , which is itself polynomial in ).

Remark 1.

This verifier definition is equivalent to the standard nondeterministic-machine view of , but it avoids machine and formal language membership notation and requires no oracle model.

Example 2

(Traveling Salesman Problem). Consider the decision version of the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP-DEC):

Instance. A complete weighted graph on labeled vertices with non-negative integer edge weights , and a threshold .

Question. Is there a Hamiltonian tour (a permutation of V) whose total weight is at most k?

Certificate (witness). A permutation of the vertices.

Verifier .

- Check that lists each vertex exactly once (permutation test).

- Compute the tour weight

- Return iff .

All steps run in time polynomial in the input length. Therefore TSP-DEC belongs to via polynomial-time verification.

2.1.2. NP-Completeness

Definition 3 (The Class NP-complete (NPC)).

A decision problem L is NP-Complete if:

- ;

- L is as hard as any problem in , meaning every problem in can be Karp-reduced to L in polynomial-time.

A Karp reduction transforms, in time that is polynomial in the size of the instance, instances of one problem into instances of another problem .

Definition 4

(Karp Reduction). Let and be decision problems. A Karp reduction from to , denoted by , is a polynomial-time computable function f such that for every input instance x of , the following holds:

In other words, solving on the transformed input allows us to solve on the original input x, and the transformation f takes time polynomial in the size of x.

Intuitively, this means that if we have an algorithm for , and we can transform any instance of into an instance of using the function f, then we can solve by first applying f and then invoking the algorithm for . The reduction ensures that the “yes”/“no” answer is preserved and that the transformation is efficient (i.e., runs in polynomial-time).

Lemma 1

(Closure of NP-completeness under Karp reductions). Let A and B be decision problems in . Assume that

- A is NP-complete;

- There is a polynomial-time Karp reduction from A to B, i.e., a polynomial-time computable transformation f that maps instances x of A to instances of B such that x is a “yes”-instance of A if and only if is a “yes”-instance of B.

Then, B is NP-complete.

Proof.

Since A is NP-complete, it is in and every decision problem C in can be reduced to A by a polynomial-time Karp reduction. Concretely, for any decision problem , there exists a polynomial-time transformation g that maps instances x of C to instances of A such that x is a “yes”-instance of C if and only if is a “yes”-instance of A.

By assumption, there is also a polynomial-time Karp reduction f from A to B: for every instance y of A, is an instance of B and y is a “yes”-instance of A if and only if is a “yes”-instance of B.

Now fix any decision problem . Define a new transformation h by composing g and f:

Because both g and f run in polynomial time, their composition h also runs in polynomial time. Moreover, for every instance x of C we have

| x is a “yes”-instance of C ⇔ |

| is a “yes”-instance of A ⇔ |

| is a “yes”-instance of B. |

Thus, h is a polynomial-time Karp reduction from C to B. Since was arbitrary, this shows that every problem in Karp-reduces to B, so B is NP-hard.

By hypothesis , so B is both NP-hard and in . Therefore, B is NP-complete. □

Note that Karp reduction is a preorder (reflexive and transitive relation). A consequence of Lemma 1 and the transitivity of Karp reduction is that, to show that a given problem X is NP-complete one need only show a Karp reduction from a known NP-complete problem to X.

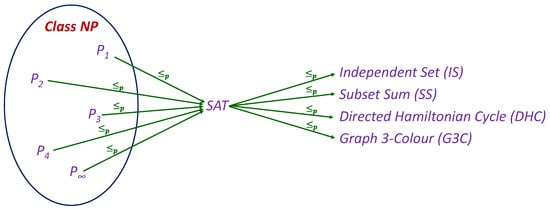

Figure 2 depicts the reduction structure underlying NP-completeness proofs. Informally, all problems in can be Karp-reduced to SAT, and SAT itself reduces to other canonical NP-complete problems such as Vertex Cover. Because Karp reductions are transitive, establishing that a problem X is NP-complete amounts to reducing some fixed NP-complete problem (e.g., SAT) to X in polynomial-time, as indicated by the arrows in the diagram.

Figure 2.

The structure of NP-Completeness established by Karp reductions (). Following the Cook-Levin theorem, any problem in NP can be reduced to SAT. SAT itself can then be reduced to other decision problems (e.g., 3-SAT, CLIQUE, TSP). The transitivity of these reductions demonstrates how these subsequent problems are also proven to be NP-Complete.

2.1.3. NP-Hardness

Definition 5.

A problem L is NP-hard if every problem in can be Karp-reduced to L in polynomial-time. Unlike NP-complete problems, NP-hard problems are not required to be in , may not be decision problems, and may not have polynomial-time verifiability. For example:

- Decision Problems: NP-complete problems, such as SAT, are also NP-hard.

- Optimization Problems: Finding the shortest Hamiltonian cycle in a graph is NP-hard but not a decision problem.

- Undecidable Problems: Problems such as the Halting Problem are NP-hard but not computable.

NP-hardness generalizes the concept of NP-completeness, capturing problems that are computationally at least as hard as the hardest problems in . Note that NP-hard problems may lie outside altogether and include problems that are undecidable (such as the Halting Problem, the Busy Beaver Problem, Post’s Correspondence Problem, and others). To summarize the preceding discussion, Table 1 presents a brief glossary of the main complexity classes used in this work—P, , NP-complete, and NP-hard—along with the informal interpretations that will be assumed throughout.

Table 1.

Glossary of key complexity classes.

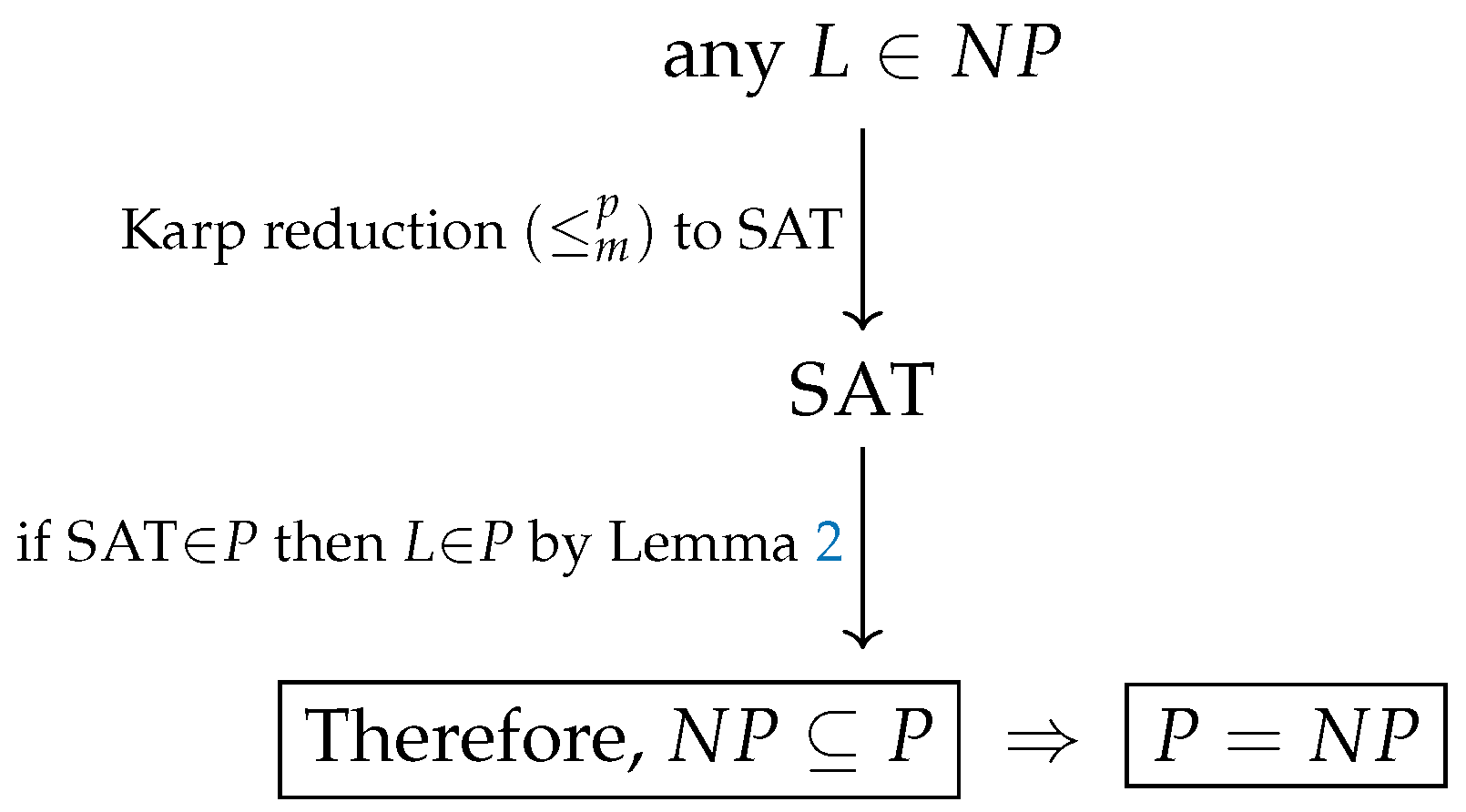

Figure 3 illustrates the informal set-theoretic relationships between the central classes, assuming . The class P is drawn as a proper subset of ; their intersection with the NP-hard region yields the NP-complete problems, while NP-hard problems outside represent optimization or decision problems at least as hard as any NP-complete problem but not themselves in .

Figure 3.

A conceptual diagram of the relationships between the major complexity classes, assuming . The class P is shown as a subset of NP. The NP-complete (NPC) class is the set of problems that are both in NP and NP-hard. This also illustrates the existence of NP-hard problems that are not in NP.

2.2. Lemmas and Consequences of Karp Reductions

Lemma 2

(Easy-in ⇒ Easy-out). If and , then .

Proof.

Given x, compute in polynomial-time and run the polynomial-time decider for B on . The composition of two polynomial-time procedures is polynomial. □

Corollary 1.

If some NP-complete problem C lies in P, then .

Proof.

For any , by Definition 3 we have . Since , Lemma 2 implies . Thus , and trivially . □

- Why NP-complete problems matter. A single polynomial-time algorithm for any NP-complete problem collapses P and by Corollary 1. We illustrate this below.

Remark 2

(On the use of “collapse”). In complexity theory, a collapse means that two or more complexity classes that are believed to be distinct are shown to be equal. For example, if any NP-complete problem (such as SAT) admits a polynomial time algorithm, then every problem in reduces to it in polynomial-time, implying —a collapse of the two classes. Similarly, the Karp–Lipton theorem [30] shows that if , then the entire polynomial hierarchy collapses to its second level, [31].

2.2.1. The Question

The question asks whether every efficiently verifiable decision problem is also efficiently decidable:

Or, equivalently:

If , then all NP-complete problems, such as SAT, would have polynomial-time algorithms. This is precisely because all NP-complete problems can be Karp-reduced to each other. If , then every standard search or optimization problem whose decision version is NP-complete has a polynomial-time algorithm (via self-reduction), assuming the objective values are polynomially bounded.

Why Does “One NP-Complete Problem” Suffice?

If C is NP-complete and , then for any problem we have a polynomial-time Karp reduction , so (compose the reduction with the decider for C). Hence . Note that this result is due to the transitivity of .

Consequences if

All NP-complete problems (e.g., SAT, 3-SAT, Clique, and Hamiltonian Cycle) admit polynomial-time algorithms. Moreover, the associated search/optimization versions for the usual problems also become polynomial-time solvable: using standard self-reductions, one can reconstruct a witness (or an optimal solution when the decision version is in P) via polynomially many calls to the decider and polynomial-time bookkeeping (Formally, implies ; for common problems (SAT, TSP decision to TSP optimization, etc.) the reconstruction uses well-known self-reduction schemes.).

Consequences if

Then, no NP-complete problem lies in P (otherwise the previous paragraph would force ). NP-complete problems are therefore those whose YES answers can be verified quickly (in polynomial-time) but, in the worst case, cannot be decided quickly.

2.3. Kolmogorov Complexity

We begin with the original definition of Kolmogorov complexity, which quantifies the informational content of strings based on the length of the shortest algorithm that generates them. We then extend this concept to computational problems, focusing on the complexity of describing solutions or algorithms for such problems. Finally, we further refine the definition to account for the complexity of algorithms within specific asymptotic time classes, particularly polynomial and exponential, in the context of the question.

2.3.1. Definition for Strings

The Kolmogorov complexity of a string x with respect to a universal Turing machine U is defined as the length of the shortest program p that, when run on U, outputs x and halts [14,32]:

The invariance theorem [32] states that the choice of U affects by at most an additive constant. Kolmogorov complexity is uncomputable [4].

This measures the information content or compressibility of the string. For example,

- A highly structured string (e.g., “1010101010...”) has low Kolmogorov complexity.

- A random string has high Kolmogorov complexity because it cannot be compressed.

A known limitation of standard Kolmogorov complexity is that it ignores the computational resources, particularly time, required for the program to produce the string. A short program may run for an intractably long time. To bridge the gap between descriptive and computational complexity, resource-bounded Kolmogorov complexity was introduced by Hartmanis [33]. For a complexity class C, the resource-bounded complexity of a string x, denoted , is defined as the length of the smallest program that outputs x and runs within the resource bounds of C. This allows for a formal study of the descriptive complexity of feasible string generation.

Remark 3

(String-level KC notation). Throughout the paper, we use:

- for plain (unbounded) Kolmogorov complexity of a string x;

- for resource-bounded Kolmogorov complexity of a string x, where C is a time/space complexity class.

When speaking informally, we use to mean ‘Kolmogorov complexity’ in this sense; in formulas we distinguish , , , and as defined below.

Relation to Other Resource-Bounded Refinements

Resource-bounded and time-sensitive refinements of Kolmogorov complexity have been explored in several directions, including Blum complexity measures for general complexity spaces [34], Levin’s complexity [35], which trades description length against running time, and Bennett’s logical depth [36], which measures the computational “history” required to generate an object from a near-minimal description. Our Time-Relative Description Complexity is closest in spirit to these resource-bounded and time-indexed measures, but applied at the problem/function level rather than the string level.

2.3.2. Time-Relative Description Complexity (TRDC)

We now extend the notion of Kolmogorov complexity from strings to computational problems. A computational problem can be represented by a (total) function where I is the set of instances and S is the set of solutions. The (unbounded) description complexity of a problem , denoted , is the length of the shortest program p that computes f:

For example, the TSP has a very small because a naïve brute-force algorithm that enumerates all possible certificates (tours) and returns the shortest one can be described by a short program.

However, inherits the same limitation as : it ignores the runtime. The short brute-force TSP algorithm, for instance, runs in exponential time. To formalize our paper’s central hypothesis, we must therefore define the resource-bounded descriptive complexity for problems. We call this Time-Relative Description Complexity (TRDC).

Definition 6

(Time-Relative Description Complexity). Let be a computational function, and let C be a complexity class (e.g., ). We define the Time-Relative Description Complexity (TRDC) of f with respect to class C, denoted , as the length of the smallest program p (for a fixed universal Turing machine U) that computes f and runs within the resource bounds of C:

Remark 4

(Overloading of K). For clarity, we intentionally overload K as follows:

- and refer to string-level Kolmogorov complexity (plain and resource-bounded), as in Section 2.3.1;

- and refer to problem-level description complexity and TRDC as in Definition 6.

The type of the argument (string x vs. function/problem f) disambiguates the meaning in every occurrence. When we discuss “high-K algorithms,” we always mean “algorithms whose description complexity is large” in the appropriate sense.

- This function-based definition of TRDC is general and powerful, as it transparently covers the three main classes of computational problems:

- Decision Problems: The function f is a predicate, mapping the instance x to an output in .

- Search Problems: The function f maps an instance x to a valid certificate (solution) s, or a special symbol ⊥ if no solution exists.

- Optimization Problems: The function f maps an instance x to a string representing the optimal solution (or its value).

In each case, represents the minimal description length of an algorithm that solves the problem within the bounds of class C.

This formalism allows us to state our hypothesis with precision. For an NP-complete problem such as TSP (represented by its function ), the TRDC with respect to is small (i.e., is small) because a naïve brute-force algorithm is short. Our hypothesis is that even if , the TRDC with respect to P may be intractably large (i.e., ).

Two Special Cases

We will use

for the problem-level TRDC associated with polynomial and exponential time. Concretely, for a given function f:

Remark 5

(Notation). Throughout the paper we use the symbol “” to denote definition by equality. For example, writing means that A is defined to be B, rather than asserting an equation that could be true or false.

Examples

Let be the function that computes the sorted form of a list. It has short classical polynomial-time algorithms, so (and is small in absolute terms). For an NP-complete decision problem such as TSP-DEC, let its characteristic function be . There is a short exponential-time template: enumerate all candidate certificates of polynomial length and verify each in polynomial-time. Hence, and is small up to encoding, whereas the finiteness of hinges on [4,14].

Basic Facts

(Analogous forms hold for search/optimization functions.)

- Finiteness characterizes classes. For a language L with characteristic function : ; . In particular, since , every has . In simpler terms: if a problem has a finite polynomial-time description, it is in P. If it only has a finite exponential-time description, it is in . All NP problems are in .

- NP via short exponential templates. For any (with function and verifier ), a fixed “enumerate-and-verify’’ schema yields a deterministic decider; thusIn simpler terms: every problem can be solved by the naïve brute-force strategy of trying all possible certificates. This always gives an exponential-time algorithm with a short description (its size is dominated by the size of the verifier).

- Dependence on . If and C is NP-complete (with function ), then while . If , then every (with function ) has . In simpler terms: whether short polynomial-time descriptions for NP-complete problems are even finite depends on the outcome of the question.

- Monotonicity across budgets. For any function f: (a looser time budget cannot increase the shortest description length). In simpler terms: if you allow yourself more time, you never need a longer program.

- Karp reduction sensitivity. If (via translator t) and C is a time class, then:by composing the shortest C-solver for B with the polynomial-time Karp reduction t. Since t is poly-time, is finite and small. In simpler terms: if problem A reduces to problem B, the complexity of describing a solver for A is at most the complexity of B plus the (small) size of the reduction.

- Orthogonality to running time. Small programs can have huge runtime (e.g., the naïve brute-force algorithm for TSP-DEC), so description length and running time are logically independent—hence, the value of the time-relative refinement.

- Uncomputability. In general, cannot be computed or even bounded algorithmically (by standard Kolmogorov arguments; cf. Rice’s theorem) [14]. In simpler terms: there is no algorithm that can always tell you the exact TRDC of a problem.

This section builds a formal framework to discuss the “descriptive size” of algorithms, moving from classical string-level Kolmogorov complexity to the Time-Relative Description Complexity of decision, search, and optimization problems. It also fixes the notational conventions we use later, especially the shorthands and for polynomial-time and exponential-time TRDC.

This progression moves from classical concepts to the paper’s central definition:

- Classical Kolmogorov Complexity: The standard definition for strings, , which is the length of the shortest program to output x. A key limitation is that this ignores runtime (a short program could run forever).

- Resource-Bounded KC for Strings: To address this, we use resource-bounded KC for strings, (Hartmanis), which is the shortest program to output x that also runs within the time/resource bounds of a complexity class C.

- KC for Problems: We then extend this idea from strings to problems. A problem is represented by a computational function f (e.g., a function that solves TSP). The unbounded is the length of the shortest program that computes f, regardless of its runtime.

- Time-Relative Description Complexity (TRDC): This is the paper’s central definition. TRDC, denoted , is the size of the smallest program that computes the problem-function f and runs within the time bounds of class C.

- Generality of TRDC: This definition is powerful because the function f can transparently represent decision problems (output 0/1), search problems (output a solution), or optimization problems (output the optimal solution).

- Key Hypothesis: This formalism allows the paper to precisely state its hypothesis: For an NP-complete problem like TSP (represented by ), its exponential-time TRDC, , is small. The hypothesis is that even if , its polynomial-time TRDC, , might be intractably large.

The section concludes by defining the shorthand and and listing several key properties of TRDC, such as its ability to characterize complexity classes () and its relationship to the question.

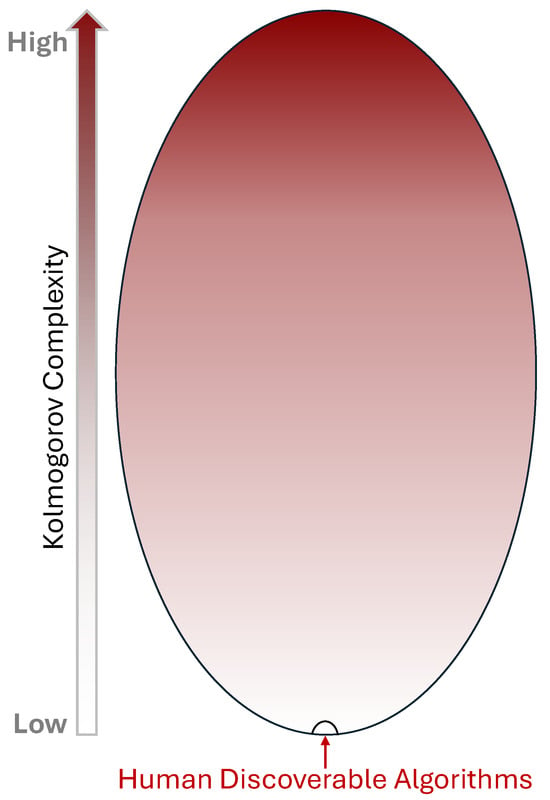

2.4. Human Discoverability of High-Description-Complexity Algorithms (High-K)

The central heuristic of this paper is that human-discoverable algorithms occupy a tiny, structured region of the full algorithmic design space for problems in (see Figure 4). We make this precise by appealing to (i) description complexity, (ii) elementary counting arguments, and (iii) human cognitive limits.

Figure 4.

The space of all algorithms ordered by descriptive (Kolmogorov) complexity. The human-discoverable region (bottom) is very small relative to the full space; efficient solutions for hard problems, if they exist, may lie outside the human-discoverable region.

2.4.1. Low Description vs. High Description

Let denote the TRDC from Definition 6. An algorithm of low description complexity has a short specification (few lines or a compact program); a high-description algorithm requires a long, intricate specification. Kolmogorov’s framework makes this formal for strings/programs and is machine-independent up to by the invariance theorem [14].

Definition 7

(Low-K and high-K algorithms). Fix a time class (in this paper typically or ). For an algorithm A solving a function f, we write for its Time-Relative Description Complexity. We use the informal terms low-K (with respect to ) for algorithms with comparatively small , and high-K for algorithms whose is large—outside the range of concise, human-comprehensible descriptions. Unless otherwise specified, “high-K efficient algorithm’’ refers to an algorithm with large (polynomial-time TRDC).

2.4.2. Counting Intuition

There are only binary strings of length , so only that many programs can be “short.” In contrast, the number of Boolean functions on n inputs is , which is astronomically larger. Therefore, almost every function cannot be realized by a short program or a small circuit [37]. Thus, “most’’ computable behaviours are of high description (or circuit) complexity: concise specifications are rare and high description complexity is typical. While this does not prove anything about specific problems, it makes it plausible that some practically useful procedures may lack short descriptions and thus be high-Kolmogorov-complexity (high-K).

For ease of reference, Table 2 summarizes the main symbols used in our treatment of Kolmogorov complexity and Time-Relative Description Complexity (TRDC). We distinguish carefully between string-level quantities (such as and ) and problem-level quantities (such as and ), and we use the shorthands Kpoly and Kexp for the TRDC of f with respect to the classes P and , respectively. The informal terms “low-K” and “high-K” are always understood relative to Kpoly for a fixed time class, while “proxy-K” denotes any computable surrogate for description length (for example, MDL-style criteria, AST size, or compressed length) used in our illustrative case studies, in the spirit of the Minimum Description Length (MDL) principle [15,38].

Table 2.

Notation and abbreviations used for Kolmogorov complexity and TRDC.

2.4.3. Human Cognitive Constraints

Human reasoning favors short, “chunkable’’ procedures; working memory and intrinsic cognitive load bound how much unstructured detail humans can manipulate [39,40]. A substantial body of work in cognitive science indicates a general simplicity bias in perception and concept learning, often formalized in terms of description length or algorithmic complexity [41,42,43,44]. This jointly suggests a discovery bias toward low-K descriptions with clear modularity, reuse, and mnemonic structure—algorithms humans can devise, verify, and teach. In contrast, the program space overwhelmingly contains behaviours whose shortest correct descriptions are long and non-obvious; hence many effective procedures may sit in high Kolmogorov complexity regions (high-K) that exceed routine human synthesis. It is therefore plausible that a significant subset of practically valuable algorithms are high-K and rarely found by unaided insight. A pragmatic response is to employ large-scale computational search (e.g., program synthesis, evolutionary search, neural/architecture search, and meta-learning) under constraints and certificates (tests, proofs, and invariants) to explore these regions safely. In short, cognitive bounds shape our algorithmic priors toward brevity and structure, while powerful compute can systematically probe beyond them to surface useful but non-succinct procedures.

2.4.4. NP Problems as a Case Study

Every admits a low-description exponential-time template that enumerates certificates and verifies them in polynomial-time. Consequently, for the characteristic function , the value is finite and typically small up to encoding [4,14]. For an NP-complete language C with characteristic function ,

Hence, the empirical asymmetry: short inefficient algorithms are easy (templates exist), whereas any efficient algorithm, if it exists, might sit at high description complexity, beyond typical human cognitive limits and discoverability.

2.4.5. Interpretation and Limits

This “high-K efficient algorithm” hypothesis is heuristic, not a statement about the truth of . It offers a plausible explanation for why decades of human effort have yielded powerful heuristics and proofs of hardness/limits, but no general polynomial-time algorithms for NP-complete problems. This heuristic is at least consonant with independent evidence that human cognition strongly favors low-description explanations and patterns [41,42,43,44], but we do not claim any direct empirical measurement of for concrete algorithms. It also motivates automated exploration of high-description code spaces, coupled with machine-checkable verification (certificates, proofs, oracles in the promise sense when appropriate), to make discovery scientifically testable.

With these preliminaries in place, we now review structural barriers (relativization, Natural Proofs, algebrization, and PCP-driven hardness) that temper expectations of simple polynomial-time solutions and motivate the later emphasis on capacity-driven automated discovery with machine-checkable certificates.

3. Structural Barriers to the Existence of Efficient Algorithms for NP-Hard Problems

Theoretical computer science has produced deep insights into why the P versus question has proved so resistant to resolution. Beyond the absence of direct progress, a set of structural results delineates what our current proof techniques can—and crucially, cannot—achieve. These theorems do not exclude the possibility that , but they map out the boundaries of existing methods and shape expectations about what kinds of breakthroughs remain plausible. Understanding these barriers is essential: it clarifies why the field has reached an impasse and motivates alternative approaches that work within these constraints, such as the capacity-driven, certificate-first framework proposed in this paper.

It is well known that if a single NP-complete problem were to be solved in polynomial time, then all problems in would be solvable in polynomial time, implying . The implications of such a result would be profound: many cryptographic protocols rely on the assumption that certain problems are hard on average [45]. If , those assumptions would collapse, and this would jeopardize many standard public-key schemes predicated on average-case hardness assumptions related to NP problems (or stronger), though the precise impact depends on average-case reductions and concrete schemes. Despite decades of effort, however, no polynomial-time algorithm has been discovered for any NP-complete problem. This lack of progress is often interpreted as indirect evidence that , although such an argument remains speculative. The absence of success is not a proof, and history reminds us that long-standing problems—such as the Four Color Theorem or Fermat’s Last Theorem—have sometimes yielded unexpectedly once new techniques emerged [46,47,48,49]. What distinguishes P versus , however, is that several foundational results suggest our existing mathematical machinery may be inherently limited.

3.1. Key Structural Results

A number of landmark theorems are frequently cited as providing structural barriers to proving or to constructing simple polynomial-time algorithms for NP-complete problems:

- The Karp–Lipton theorem [30,31] shows that if , then the polynomial hierarchy collapses to its second level. This implies that any approach relying on non-uniform circuits or advice strings must confront the risk of trivializing large portions of the hierarchy.

- The Natural Proofs barrier, due to Razborov and Rudich (1997), explains why many combinatorial circuit-lower-bound techniques cannot separate P from under standard cryptographic assumptions [6].

- The Probabilistically Checkable Proofs (PCPs) theorem underlies strong hardness-of-approximation results for many NP-hard problems [8], showing that even approximate solutions can remain intractable.

- Intuition for non-specialists.

Very roughly, Karp–Lipton says that if had “small” non-uniform circuit families, large parts of the polynomial hierarchy would collapse; Natural Proofs explains why a broad class of combinatorial lower-bound arguments seem unable to rule out such small circuits, assuming standard cryptographic primitives exist; and the PCP theorem shows that even obtaining good constant-factor approximations for some NP-hard problems would already imply unexpectedly strong algorithmic consequences. Together they indicate that many of the most straightforward proof strategies for separating P from are blocked for highly structured reasons, not just for lack of ingenuity.

Taken together, these results suggest that our current proof paradigms are not merely incomplete but structurally constrained. They show where ingenuity alone may not suffice and where new conceptual tools, computational methods, or discovery frameworks must intervene.

3.2. The ETH/SETH Context

- ETH. There is no -time algorithm for 3-SAT [50].

- SETH. For every there exists k such that k-SAT cannot be solved in time [13].

- Intuition for non-specialists.

ETH and SETH are widely used working hypotheses that say, informally, that even the fastest algorithms for SAT still need essentially exponential time in the number of variables. Assuming them lets us argue that many improvements people might hope for (for example, shaving an exponential factor down to quasi-polynomial time) would already contradict these conjectures. In this paper we do not rely on ETH/SETH as axioms, but we use them as a backdrop: they illustrate how seriously the community takes the possibility that certain exponential-time behaviours may be intrinsic.

These conjectures calibrate expectations about how much improvement is realistically possible. Under ETH, many classic NP-hard problems are unlikely to admit sub-exponential-time algorithms, while SETH yields fine-grained lower bounds for k-SAT and related problems. For this paper, ETH and SETH serve as a backdrop rather than a target: our capacity-driven automated discovery approach operates within these assumptions, seeking smaller exponential bases, improved constants, and broader fixed-parameter tractability—without claiming sub-exponential breakthroughs that would contradict them.

- Interpretive note.

ETH and SETH concern runtime complexity, not descriptional complexity. They do not imply that any efficient algorithm for an NP-complete problem must have high Kolmogorov complexity. Our claim is heuristic: taken together with known proof technique barriers, these conjectures suggest that if polynomial-time algorithms for NP-complete problems exist, they are unlikely to arise from today’s simple, low-description methods. Such algorithms—if they exist—may occupy regions of high descriptive complexity, beyond unaided human discoverability, but possibly still within reach of systematic computational search.

3.3. The Karp–Lipton Theorem

The Karp–Lipton theorem [30,31] provides an early example of a structural implication linking to non-uniform computation. It states that if , then the polynomial hierarchy (PH) collapses to its second level:

If , then [30,31].

Intuitively, this means that if nondeterministic polynomial-time problems could be solved by deterministic polynomial-time machines with polynomial-size advice strings (non-uniform circuits), the rich hierarchy of alternating quantifiers that defines PH would reduce to just two levels. Such a collapse would be deeply counter-intuitive and is viewed as strong evidence against . In our context, the theorem illustrates how even seemingly modest containments can have far-reaching consequences, and why uniform, verifiable discovery methods—as opposed to opaque non-uniform constructions—are desirable.

3.4. The Natural Proofs Barrier

Razborov and Rudich’s Natural Proofs framework explains why many circuit-lower-bound techniques may not scale to separate P from [6] (see also [45], §20.4). A property of Boolean functions on n inputs is said to be:

- Large if it holds for a non-negligible fraction of all functions.

- Constructive if membership can be decided efficiently given the truth table.

- Useful against a circuit class if it excludes all functions computable by circuits of size within but includes at least one explicit hard family .

3.4.1. Barrier (Conditional)

Assuming the existence of strong pseudorandom objects secure against -circuits, there is no property that is simultaneously large, constructive, and useful against [6]. In particular, under standard cryptographic assumptions, no “natural” combinatorial property can prove super-polynomial lower bounds for .

3.4.2. Interpretation

This framework captures a paradox: methods that are too explicit or uniform tend to be powerless against the very hardness they hope to expose. For this paper’s argument, the analogy is instructive. Human designed algorithms—valued for simplicity and transparency—may, by virtue of those very properties, be confined to low-complexity regions of the design space. If efficient algorithms for NP-complete problems exist, they may therefore inhabit regions that are neither natural nor human-legible, reinforcing the relevance of automated, high-capacity search guided by machine-verifiable certification.

3.5. The PCP Theorem and the Hardness of Approximation

The Probabilistically Checkable Proofs (PCPs) theorem revolutionized our view of : it shows that proofs can be verified probabilistically by inspecting only a few randomly chosen bits. Formally,

meaning that membership in can be verified using logarithmic randomness and a constant number of queries [8]. This result established deep connections between verification, randomness, and inapproximability.

Table 3 summarizes three major structural obstacles to resolving —relativization, natural proofs, and algebrization—each showing that broad families of otherwise-plausible proof techniques provably cannot resolve the question, thereby constraining what a successful separation strategy must look like.

Table 3.

Summary of Formal Barriers to Resolving .

3.5.1. Consequences for Approximation

The PCP machinery leads to gap reductions showing that even approximate solutions are hard to compute:

- Max-3SAT: No polynomial-time algorithm can achieve a ratio better than for any unless [9].

- Vertex Cover: Approximating within a factor of is NP-hard [51]; the best known ratio is 2.

- Set Cover: Approximating within is hard unless [10].

- Max Clique/Chromatic Number: -approximation is NP-hard for any fixed [52,53].

3.5.2. Interpretation

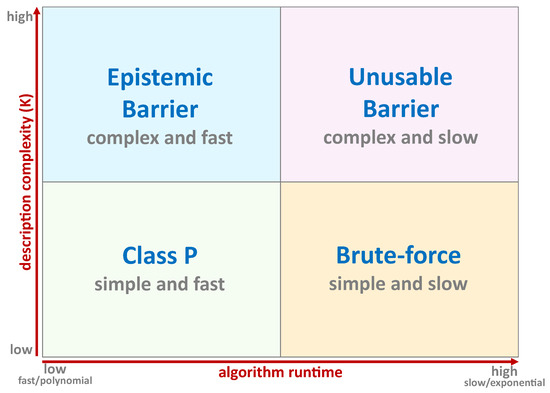

The PCP theorem re-frames intractability: it is not only difficult to find exact solutions but even to approximate them within tight bounds. Yet, it also offers a silver lining by highlighting the role of verification. Hardness-of-approximation results demonstrate that rigorous certificates of quality—approximation ratios, dual bounds, or proof logs—are essential for establishing trust in heuristic solutions. This observation directly aligns with the certificate-first philosophy advocated in this paper: progress may come not from breaking these barriers but from working within them, developing auditable heuristics that trade interpretability for verifiable performance. With this, we can state our main premise. We propose that a vast space of algorithms is hidden from human-led discovery by an ’epistemic barrier’ of high description (high-K) complexity (Figure 5). We call the practical consequence of this barrier the discoverability asymmetry.

Figure 5.

A visualization of this paper’s epistemic barrier premise, mapping the problem-solving space by Algorithm Runtime (x-axis) and Description Complexity K (y-axis). The Epistemic Barrier (top-left) represents hypothetical polynomial-time algorithms that are too complex (high–K) for unaided human discovery. This is contrasted with known Class P problems (bottom-left), which are both fast and simple (low–K) to discover.

3.5.3. Synthesis

The Karp–Lipton theorem, the Natural Proofs barrier, and the PCP theorem each describe a different frontier of limitation: non-uniformity, naturalness, and approximation. Together with ETH and SETH, they define a landscape where exact polynomial-time algorithms for NP-complete problems appear increasingly implausible. For this reason, future progress must focus on what remains open—the systematic, verifiable discovery of high-performing heuristics and approximation methods within these constraints. Our approach views this as an opportunity rather than a defeat: by combining computational capacity with certification, we can explore the algorithmic frontier responsibly and productively, even without resolving itself.

4. Automated Algorithm/Heuristic Discovery: A New Frontier

Automated discovery, as used here, grows out of familiar lines of work. From empirical algorithms comes the idea of portfolios and automatic configuration, where strength comes from choosing well rather than insisting on a single universal solver [25,26]. From learning-augmented algorithms comes the view that predictions can serve as advice, with safeguards that limit the damage when the advice is wrong [54,55,56]. From implicit computational complexity comes polytime-by-construction design, in which the language itself carries the resource discipline [57].

The aim is not to propose a fixed pipeline but to suggest a change in perspective. With modern compute it now becomes feasible to explore program spaces that extend far beyond what can be examined by humans. What matters is not opacity for its own sake, but reach: compact templates and systematic search may surface high–K procedures that would be hard for humans to invent directly. Credibility then follows from what travels with the code—proof logs, formal proofs, and dual bounds—so that claims can be checked and trusted on an instance-by-instance basis.

What follows offers a shared vocabulary and a few recurring patterns of discovery. The targets remain concrete: better approximations within known floors, broader fixed-parameter regimes, and smaller exponential bases, together with the evidence that allows such results to enter practice.

4.1. Definitions (Model-Agnostic)

For clarity, we use the following terms informally and in line with standard texts.

- Heuristic. A polynomial-time procedure that returns a feasible decision or solution on every input, typically without a worst-case optimality bound [58]. Randomised variants run in expected polynomial time or succeed with high probability.

- Approximation algorithm. For minimization with optimum , an algorithm A is an -approximation if for all instances of size n, with polynomial running time (and analogously for maximization). Canonical regimes include constant-factor, PTAS/EPTAS, and polylogarithmic-factor approximations [59,60].

- Meta-heuristic. A higher-level search policy—e.g., evolutionary schemes, simulated annealing, or reinforcement learning—that explores a space of concrete heuristics or pipelines adapted to a target distribution [61,62].

- Algorithmic discovery system. Given a design space (programs, relaxations, and proof tactics), a distribution , and an objective J (e.g., certified gap or runtime), the system searches for that scores well under J within resource limits, and emits certificates when applicable, such as LP/SDP dual bounds from linear relaxations or primal–dual methods [63] and proof logs for SAT instances [16]. Crucially, this framework decouples discovery from correctness: the search process itself need not be correct-by-construction, provided that its outputs can be rigorously validated ex post by an independent verifier.

4.2. Discovery Paradigms

There is no single road to discovery; several strands point in the same direction. One is search and synthesis: local or stochastic search over code and algorithmic skeletons with equivalence checking (Massalin’s Superoptimizer; STOKE) [64,65], SAT/SMT-guided construction of combinatorial gadgets such as optimal sorting networks [66], and recent reinforcement-learning setups for small algorithmic kernels [19].

Another is learning-guided generation. Systems that generate or repair code by tests and specifications (e.g., AlphaCode) and program search guided by LLMs with formal validation (e.g., FunSearch) show how statistical guidance and verification can coexist [20,21].

A third strand is neuro-symbolic structure. Syntax-guided synthesis (SyGuS), equality saturation with e-graphs, and wake–sleep library growth (DreamCoder) combine search with inductive bias from symbolic structure [22,23,24].

Finally, evolutionary and RL approaches remain natural for structured search over algorithmic design spaces, especially for tuning heuristics or inner loops (e.g., learned branching or cutting policies), where compact policies can be discovered and then judged by certificates [61,67,68]. Recent work on AlphaTensor, which discovered new matrix multiplication algorithms via RL over tensor decompositions while retaining formal guarantees on correctness and running time [69], is a concrete example of this “high-capacity search plus verification” pattern.

4.3. Targets for Approximation and Heuristics

Reductions and relaxations. Automated reductions, LP/SDP relaxations, and learned policies for branching and cutting provide a flexible substrate. Dual-feasible solutions and lower bounds certify quality, while SAT-family problems admit independently checkable proof logs [45,63].

Rounding schemes. Classical rounding ideas can be viewed as templates to explore, with guarantees inherited from the template: randomised rounding [70], SDP-based rounding such as Goemans–Williamson for MAX-CUT [71], and metric embeddings that translate structure into approximation [72].

Algorithmic skeletons. Sound skeletons—local search with a potential function, primal–dual methods, greedy with exchange arguments—set the envelope of correctness. Searched or learned choices (moves, neighborhoods, and tie-breaks) then tune behaviour within that envelope [59,60].

4.4. Evidence and Evaluation

Because this is a position paper, the emphasis is on what tends to constitute persuasive evidence. Correctness comes first: constraint checks for feasibility; for decision tasks, proof logs or cross-verified certificates where available. When worst-case guarantees exist they should be stated; where they are out of reach, per-instance certified gaps via primal–dual bounds are informative. Efficiency is often clearer from anytime profiles (solution quality over time on fixed hardware) than from a single headline number. Generalization benefits from clean train/test splits, stress outside the training distribution, and simple ablations for learned components. Reproducibility follows from releasing code, seeds, models, datasets, and the verification artifacts themselves (certificates and any auxiliary material needed to independently check results such as proofs, logs, or counterexamples).

4.5. High-K Perspective, Limits, and Compute as an Enabler

High–K artifacts—large parameterisations or intricate codelets—may lie beyond familiar design priors yet remain straightforward to verify. The working view is that worst-case optimality for canonical NP-hard problems is unlikely, so practice leans on heuristics and approximations; automated discovery, constrained by polytime-by-construction scaffolds and paired with certificates, offers a way to surface stronger ones and, at times, to tighten provable bounds. Compute changes what is plausible: modern compute clusters make it realistic to explore vast program spaces, from code optimization to small-scale algorithm design [19,20,21,65]. The same scale brings predictable risks—benchmark overfitting, reward hacking, unverifiable “speedups,” distribution shift—best mitigated by certified outputs, standard verification tools, and transparent reporting.

4.6. Observations from LLMs and Scaling

- Scope and stance.

We use large language models (LLMs) as an analogy and hypothesis-source, not as direct evidence about the question. The claim here is explicitly methodological: expanding capacity (e.g., model size, training data) can enable search to reach complex—potentially high–K—mappings, and applying a certificate-first mindset ensures that artifacts remain auditable.

- Empirical regularities in LLMs.

Empirical studies of LLMs demonstrate two relevant patterns. First, predictive loss scales in a smooth power-law fashion with model size, dataset size and compute budget. For example, Kaplan et al. found that negative log-likelihood loss L approximately follows where N = parameters, D = tokens [73]. Second, a notable phenomenon called “emergent abilities” appears: abilities that are essentially absent at smaller scales yet appear once a model crosses a certain size threshold. In the seminal work, Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models [74] the authors define emergent abilities as “not present in smaller-scale models but present in large-scale models” and not predictable simply by extrapolation. A recent survey reviews this phenomenon in detail, noting that while scale correlates with emergence, the exact mechanism remains unclear [75]. Together, these findings motivate the working intuition that larger capacity expands the reachable function space for model-search, including functions of higher descriptive complexity.

From analogy to testable hypothesis.

Let denote the mapping implemented by a trained model with parameter vector . Classical Kolmogorov complexity is uncomputable; accordingly we propose operational proxy measures of description complexity and state falsifiable predictions.

4.6.1. Proxy Measures for Description Complexity

- Minimum Description Length (MDL) proxy:This combines model size with residual uncertainty after training, following the Minimum Description Length principle [15,38] and in line with recent work that explicitly studies the description length of deep neural models [76].

- Compressed program-size proxy: size of an executable (model weights + inference code) that reproduces on the distribution within tolerance .

- Distillation or compression gap proxy: given a distilled/rule-extracted surrogate g that approximates to error , compute ; a large gap suggests high inherent complexity in .

4.6.2. Falsifiable Predictions (Hypotheses)

- P1

- Capacity–Reachability: For fixed design of search/training procedure and fixed distribution , increasing parameter budget (N) or data/dataset size extends the reachable space of mappings. Some mappings (e.g., long-range algorithmic structure) are only reached above certain scale thresholds (as in emergent ability findings).

- P2

- Description-Complexity Variation: Among models trained under compute-optimal scaling, improved task performance correlates with either increased model-size term or decreased residual term in . Hence, total may increase or decrease, but ideally remains bounded while performance improves—signaling higher complexity but still efficient encoding.

- P3

- Compression Gap Persistence: Mappings accessed only at high capacity will show a persistent gap between the size of the full model and the size of any distilled/rule surrogate; i.e., complexity cannot easily be compressed without loss.

- P4

- Transfer to Algorithm Discovery: In algorithmic/heuristic search domains (SAT, TSP, etc.), if one expands the search or policy-class capacity (e.g., more parameters, larger architectures, deeper templates), then the larger class should more frequently yield certified improvements (proof logs, dual bounds) than smaller classes – even if those discoveries are opaque.

- Minimal certificate-first micro-experiments.

We propose two low-overhead studies to instantiate these ideas in the algorithmic domain:

- SAT branching policy search: Parameterise branching/learnt-clause deletion policies of size ; measure fraction of solved instances and total proof codelength (DRAT/FRAT) on held-out benchmarks, requiring independently checkable proof logs. Hypothesis P4: larger s yields shorter proofs or higher solve-rate more often.

- Metric TSP heuristic search: Explore insertion/3–opt neighborhood policies with increasing parameter class; certify solution quality using 1-tree or Lagrangian dual lower bounds and report certified gap and time-to-target. Hypothesis P4: larger classes achieve smaller certified gaps (under equal compute) more often.

- Clarifying what we are not claiming.

We do not assert that parameter count equals Kolmogorov complexity, nor that scaling alone yields AGI, nor that LLM internal mappings correspond directly to high–K in the formal sense. The relation between circuit/program complexity and neural parameterisations is open (see e.g., Nonuniform ACC Circuit Lower Bounds by Williams). Our point is narrower: in practical terms, capacity expansion enables search into richer function spaces; if those spaces contain functions that are hard to compress, then our certificate-first workflow provides a path to trusted discovery.

4.6.3. Takeaway for This Paper

LLMs motivate a practical design prior: use capacity to explore, and use certificates to trust. The analogy suggests how to search (expand capacity, richer representations), while the core of the paper remains about what is certified (proof logs, dual bounds, measurable description proxies) when artifacts emerge.

5. Case Studies: Applying the Workflow

This section is illustrative. It shows how the certificate-first workflow (see Figure 6) may apply to canonical problems. It does not present experiments. The goal is to make the method concrete without prescribing one toolchain.

Figure 6.

The proposed “certificate-first” workflow for automated discovery. (1) The “discovery” engine systematically searches the High-K space to generate (2) an unverified “candidate” algorithm. This candidate is then passed to (3) the “certification” step (a polynomial-time verifier) to formally check its properties, resulting in (4) a final, Certified Artifact.

- A workable protocol.

(1) Fix a task and an instance distribution. (2) Choose baselines users already trust. (3) Specify a compact search space or DSL and a proxy for description length (e.g., AST nodes or compressed size). (4) Require machine-checkable certificates. (5) Report practical metrics: gap, time-to-target, success rate, fraction certified.

5.1. SAT (CNF)

Targets. Better branching, clause learning, and clause-deletion policies. Search space. Small policies over clause and variable features; proxy-K by AST size or token count. Certificates. Verify UNSAT with DRAT/FRAT; validate SAT by replaying assignments [16,17,77]. Context. Portfolios and configuration improve robustness; they integrate naturally with certificate-first outputs [25,26]. Outcome. A discovered policy is acceptable once it produces proofs or checkable models on the target distribution.

5.2. Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP)

Targets. Lower tour gaps and stronger anytime behaviour. Search space. Insertion rules or LKH parameter templates; proxy-K by rule length [78]. Certificates. Use 1-tree and related relaxations as lower bounds; export tours and bounds with Concorde-style utilities [79,80]. Outcome. A policy is credible when tours come with lower bounds that certify the reported gaps.

5.3. Vertex Cover and Set Cover

Targets. Simple rounding and local-improvement templates. Search space. Short heuristics that map LP or greedy features to choices; proxy-K by template length. Certificates. Dual-feasible solutions certify costs; hardness thresholds calibrate expectations [10,51,70,81]. Outcome. New templates are useful when they offer certified gaps or better anytime profiles on the intended distribution.

5.4. Learning-Augmented and Discovery Tools

Role. Predictions serve as advice with robustness guarantees; portfolios hedge uncertainty [26,54,55,56]. Program search and RL can propose compact rules; superoptimization and recent discovery systems show feasibility on small domains [19,20,21,64,65,66]. Certificate-first turns such proposals into auditable artifacts.

Scope

This is a position paper. This section does not claim superiority over mature solvers. It shows how to pair capacity and search with certificates and structure so that high-description solutions—if found—are scientifically usable.

6. Implications for

If , then the longstanding intuition is confirmed: exact polynomial-time algorithms for NP-complete problems are, in the worst case, out of reach. This does not close off progress, but it shifts what “progress” means. Advances then come from approximation, from exploiting structure through parameterised approaches, from tightening exponential-time algorithms, or from combining diverse methods into robust portfolios. Each of these directions represents ways of performing better even when the ultimate barrier remains.

Seen in this light, the focus moves away from hoping for a breakthrough algorithm that overturns complexity theory, and toward a pragmatic exploration of what can be achieved within known limits. Certificates and verifiable relaxations are valuable because they allow even opaque or high-complexity procedures to be trusted. If P were ever shown equal to , the same emphasis on auditable artifacts would still matter: high-K algorithms would need to be made scientifically usable.

The broader implication is that the question, while unresolved, should not dominate practice. Assuming encourages a re-framing: instead of waiting for resolution, we can treat complexity-theoretic limits as the backdrop against which useful heuristics, approximations, and verifiable improvements are sought.

7. Discussion

In this section, we interpret the methodological and practical implications of the proposed framework and its limitations. The stance we advocate is deliberately pragmatic: explore high-description-complexity (high-K) spaces while anchoring discovery to independently checkable certificates. Even without resolving , this pairing—capacity for discovery plus auditable evidence—can yield stronger heuristics and approximation procedures and, in some cases, tighten known bounds.

Our emphasis shifts from algorithms that are simple to narrate toward treating discovery itself as an object of study. Capacity-rich systems can traverse design spaces that unaided reasoning is unlikely to explore. When such searches are paired with epistemic safeguards—SAT proof logs (DRAT/FRAT), LP/SDP dual bounds, 1-tree relaxations, or equivalence checking—the resulting artifacts become auditable and trustworthy. In this re-framing, understanding shifts from producing hand-crafted algorithms to verifying the correctness of artifacts and bounding their behavior.

Assuming , exact polynomial-time algorithms for NP-complete problems do not exist. Progress must then be understood in other terms: stronger approximation methods within known hardness floors, parameterised techniques that exploit hidden structure, incremental improvements to exponential-time algorithms, or more robust combinations of solvers into portfolios. What counts as success in this setting is not a definitive breakthrough but the production of efficiently computable procedures whose reliability is guaranteed by independent certification rather than by intuitive transparency.

The proposed framework is deliberately domain-agnostic. In SAT and related constraint problems, proof logs render unsatisfiability independently checkable. In graph optimization and routing, dual bounds and relaxations serve a similar role. Discovery costs can be absorbed offline, while deployed procedures remain polynomial time and instance-auditable. This way, even when artifacts are opaque or high-K, their use can be grounded in verifiable evidence.

There are, of course, limitations and risks. High-K artifacts may be brittle, or they may conceal dependencies that are difficult to manage. Certification mitigates some of these issues but does not eliminate them. Benchmarks can be overfit; data distributions can shift; compute and energy costs are nontrivial. Claims of speed or optimality carry weight only when tied to released artifacts—code, seeds, models, and certificates—that allow independent checking, validation, and reproduction.

Several open directions suggest themselves. Polytime-by-construction DSLs could gain richer expressivity while preserving verifiability. Neuro-symbolic approaches might combine relaxations and rounding with machine-checked proofs. Transfer across problems may be enabled by embeddings or e-graphs, provided certification is preserved. Learning-augmented and portfolio methods can hedge against distributional uncertainty, especially when accompanied by explicit certificate-coverage guarantees. Community benchmarks would benefit from requiring not only solutions but also certificates of correctness.

Within this picture, our conclusions extend and organise prior work rather than contradict it. Classical barrier results, description-length principles, and automated discovery techniques remain intact; we treat them as constraints and tools. The contribution of the present framework is to integrate these strands into a single “capacity plus certification” viewpoint that treats high-K exploration as routine, insists on machine-checkable evidence, and offers a common language for comparing progress across domains.

8. Conclusions

The broader message of this paper is methodological. Algorithm design has often assumed that useful procedures must be human-discoverable and human-comprehensible. We have argued that this is a restrictive assumption. Once one takes seriously the possibility of high-description-complexity algorithms, it becomes natural to view computational capacity and systematic search as central tools for discovery, and to decouple how an artifact is found from how it is justified.

The proposed capacity plus certification perspective treats high-K exploration as routine while requiring that new artifacts arrive with machine-checkable evidence. In this view, high-capacity search and learning systems are not competitors to classical theory but instruments that operate within its constraints. Structural results about barriers to resolving , description-length principles, and existing techniques for automated search and verification remain valid; our conclusions extend and organise these strands by placing them inside a unified framework that emphasises verifiable discovery over explicit construction of low-complexity algorithms.

- Contributions.

The main contributions of this paper are conceptual and programmatic. (i) We articulate a capacity plus certificates framing for algorithmic discovery in high-K spaces. (ii) We argue for machine-checkable evidence (such as proof logs, dual bounds, relaxation-based bounds, and equivalence checks) as the epistemic basis for trust in opaque artifacts. (iii) We sketch a domain-agnostic workflow that decouples costly offline discovery from lightweight, instance-auditable deployment.

- Limitations.

The arguments presented here are heuristic and do not bear on the truth of . Certification does not prevent brittleness, distribution shift, or hidden dependencies, and it cannot, by itself, guarantee that discovered procedures are optimal for all instances of interest. Compute and energy budgets also constrain feasibility. The framework should therefore be seen as a way to organise and focus research efforts, not as a definitive resolution of long-standing questions.

- Outlook.

Progress will come from operationalising verifiable discovery pipelines in concrete domains: richer polytime-by-construction DSLs, neuro-symbolic relaxations equipped with proofs, portfolio methods with explicit guarantees on certificate coverage, and benchmarks that require certified artifacts rather than bare solutions. In short, capacity is the engine of discovery and certification is its safeguard. By taking both seriously, we can make steady, auditable progress on hard problems without presupposing a final answer to .

Possible Threats to Validity

- (1)

- Benchmark bias: Overfitting to public instances; this risk can be mitigated by using held-out distributions and disclosing random seeds.

- (2)

- Certificate coverage: Proofs and bounds may not cover all claim types; it is important to report clearly what is certified and what is supported only by empirical evidence.

- (3)

- Reproducibility: Reproducible research requires releasing code, models, seeds, and certificates, and using deterministic or well-documented runs where possible.

- (4)

- Resource limits: Compute and energy budgets constrain which discovery pipelines are practical; reporting these budgets and including ablation studies that separate search from verification cost helps to clarify what is scalable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.; methodology, J.A.; validation, J.A., C.L., and E.C.; formal analysis, J.A.; investigation, J.A.; resources, J.A., C.L., and E.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.; writing—review and editing, J.A., C.L., and E.C.; visualization, J.A.; supervision, J.A., C.L., and E.C.; project administration, J.A., C.L., and E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement