Abstract

Precise recognition and localization of electronic components on printed circuit boards (PCBs) are crucial for industrial automation tasks, including robotic disassembly, high-precision assembly, and quality inspection. However, strong visual interference from silkscreen characters, copper traces, solder pads, and densely packed small components often degrades the accuracy of deep learning-based detectors, particularly under complex industrial imaging conditions. This paper presents a two-stage, coarse-to-fine PCB component localization framework based on an optimized YOLOv11 architecture and a sub-pixel geometric refinement module. The proposed method enhances the backbone with a Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) to suppress background noise and strengthen discriminative features. It also integrates a tiny-object detection branch and a weighted Bi-directional Feature Pyramid Network (BiFPN) for more effective multi-scale feature fusion, and it employs a customized hybrid loss with vertex-offset supervision to enable pose-aware bounding box regression. In the second stage, the coarse predictions guide contour-based sub-pixel fitting using template geometry to achieve industrial-grade precision. Experiments show significant improvements over baseline YOLOv11, particularly for small and densely arranged components, indicating that the proposed approach meets the stringent requirements of industrial robotic disassembly.

Keywords:

PCB component detection; YOLOv11; attention mechanisms; Bi-directional feature pyramid network; sub-pixel localization MSC:

68T07

1. Introduction

Industrial automation increasingly requires precise perception of electronic components on printed circuit boards (PCBs), especially for robotic disassembly, repair, recycling, and high-precision quality inspection. These tasks demand accurate recognition of component categories, detailed structural understanding, and pose estimation at sub-pixel precision. However, PCB images exhibit dense silkscreen characters, copper traces, solder pads, and cluttered layouts that generate strong visual interference, significantly degrading the performance of generic deep learning-based detectors. Small components, such as 0201/0402 resistors, are particularly susceptible to feature loss in deep networks, while larger integrated circuits (ICs) may appear at arbitrary orientations requiring precise rotation estimation rather than axis-aligned bounding boxes.

Deep learning has transformed object detection over the last decade. Region-proposal approaches such as R-CNN and Faster R-CNN [1] pioneered high-quality detection pipelines, while the YOLO family [2] and SSD [3] enabled real-time single-stage detection. Improvements such as Focal Loss [4] and Feature Pyramid Networks (FPN) [5] strengthened detection under class imbalance and multi-scale conditions. Later works including EfficientDet with BiFPN [6], DETR transformer-based detection [7], YOLOv4 [8], and Scaled-YOLOv4 [9] further advanced accuracy and robustness. Despite these advances, transferring generic models to PCB imagery remains challenging due to the severe background clutter and the presence of extremely small components.

Attention mechanisms have provided powerful tools for enhancing feature discriminability. Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) modules [10], CBAM [11], global-transformer attention in ViT [12], and attention-augmented CNNs [13] have shown strong capabilities in suppressing irrelevant context and highlighting task-relevant regions. These properties are crucial in PCB imagery, where misleading textures such as parallel traces, silkscreen symbols, and solder pads can closely resemble true components.

Meanwhile, keypoint-based and pose-aware detectors such as CornerNet [14], CenterNet [15], HRNet [16], and stacked hourglass networks [17] demonstrated the importance of geometric reasoning beyond bounding-box regression—an essential capability for robotic manipulation of electronic components where orientation and vertex locations must be estimated precisely.

In PCB-specific vision research, a variety of deep learning-based solutions have been proposed. Representative works include the PCB defect dataset and baseline detection benchmarks released by [18], a variety of CNN-based automated optical inspection (AOI) pipelines for surface defect classification [19], and YOLO-family detectors adapted for PCB component and defect inspection [20]. Recent studies further investigate improved detection of small defects using attention-enhanced networks and feature-pyramid refinements [21]. Despite these advances, most prior systems focus on pixel-wise defect segmentation or bounding-box detection; few works address the combined requirement of robust detection of micro-scale PCB features and sub-pixel geometric localization accuracy, which is essential for industrial robot alignment and precision assembly.

Traditional industrial vision methods—such as template matching, edge detection, and geometric metrology—remain indispensable in high-accuracy automation tasks. Classical techniques including the SUSAN operator [22] and the Canny edge detector [23] demonstrate robust low-level feature extraction, while modern image-alignment and registration methods provide the foundation for sub-pixel localization and precise template matching (e.g., Lucas–Kanade frameworks and extensions [24]). However, classical methods typically degrade under variations in lighting, noise, and unseen defect types, motivating hybrid AOI pipelines that combine deep learning for robust feature detection with classical geometric refinement for sub-pixel alignment accuracy.

Given the limitations in existing PCB component detection—small-object sensitivity, background interference, pose estimation, and lack of sub-pixel accuracy—there is a need for a unified framework that integrates advanced deep learning with precise geometric modeling. This work proposes a PCB-specific detection and localization algorithm that combines deep neural feature extraction, attention-based noise suppression, multi-scale feature enhancement, and a geometry-based refinement stage. Unlike conventional approaches, the system predicts both bounding boxes and vertex offsets that encode component orientation, while a subsequent contour-based stage pushes precision to the sub-pixel level. The contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- A specialized, high-precision PCB component dataset is constructed, featuring multi-modal annotations that include not only bounding boxes but also pin-level vertex coordinates for thousands of components, enabling supervised learning of pose and fine-grained geometry.

- An enhanced YOLOv11 architecture tailored for PCB imagery, incorporating CBAM attention and a BiFPN-based multi-scale fusion neck to effectively suppress silkscreen/trace-induced background interference, significantly improving the detection robustness of small and densely arranged components.

- A pose-aware decoupled detection head with vertex-offset regression is introduced, allowing the model to predict fine-grained geometric details, such as component rotation and key pin positions, which conventional axis-aligned bounding boxes cannot capture.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 details the proposed two-stage methodology, including the construction of the PCB component dataset, the enhanced YOLOv11-based coarse localization network, and the sub-pixel geometric refinement procedure. Section 3 presents the experimental setup and evaluates detection and localization performance on the constructed dataset. Section 4 provides a technical discussion of the results, including the benefits and limitations of the proposed framework. Finally, Section 5 concludes this study and outlines future research directions.

2. Methods

2.1. Dataset Construction and Pose Annotation

To support high-precision pose estimation of PCB components under complex industrial conditions, we constructed a dedicated dataset containing both bounding-box and pose-level annotations. All images are captured with a high-resolution industrial camera (1920 × 1080) in factory environments, covering variations in illumination, contamination, PCB density, and device categories. A total of 10,000 PCB images are collected, containing over 150,000 annotated component instances across 20 devices (e.g., resistors, capacitors, inductors, QFP ICs, BGA chips, and connectors). Approximately 50% of the instances are small objects (< pixels), which is essential for evaluating robustness in dense-component scenarios.

Unlike standard PCB datasets that only include axis-aligned bounding boxes, our dataset introduces a multi-modal pose annotation strategy to capture fine-grained structural characteristics of components. In addition to the class label and bounding box, selected devices—particularly ICs and connectors that require precision manipulation—were annotated with key structural vertices. For chips, this includes the four corner pin locations; for connectors, the alignment vertex and pin-array reference points. These high-precision vertex labels serve as ground-truth supervision for the vertex-offset regression branch in the proposed model.

To enhance generalization across real production environments, we applied a series of augmentation techniques: random cropping, photometric distortion, Gaussian noise injection, and MOSAIC composition [8]. The MOSAIC strategy is especially critical for training the tiny-object detection branch, as it places multiple small components in a single forward pass, improving multi-target spatial reasoning.

2.2. Coarse Localization with Enhanced YOLOv11

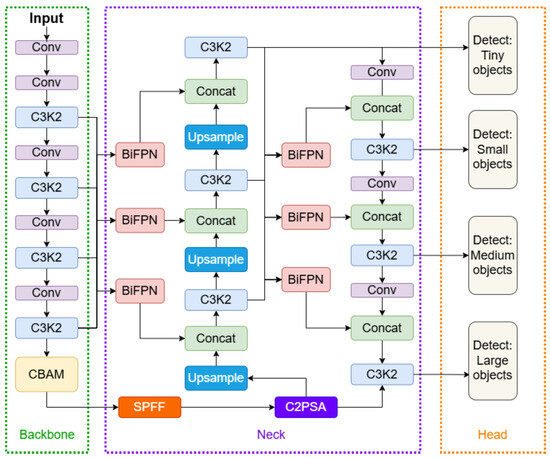

The coarse localization stage produces an initial estimate of location and pose of each device by extending the standard YOLOv11 framework in three coordinated aspects: enhanced feature extraction, multi-scale fusion with a tiny-object branch, and a pose-aware decoupled detection head. Figure 1 shows the overall architecture of our framework.

Figure 1.

Overall architecture of the enhanced YOLOv11 detection network, integrating CBAM attention in the backbone, BiFPN-based multi-scale feature fusion in the neck, and a decoupled detection head with vertex-offset regression for pose-aware PCB component detection.

2.2.1. Backbone Enhancement with CBAM Attention

To address the severe background interference present in PCB imagery—such as silkscreen characters, copper traces, and solder pads—we embed the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) into the deep layers of the YOLOv11 backbone. CBAM refines feature representation through two sequential attention operations: Channel Attention Module (CAM), which determines what to focus on, and Spatial Attention Module (SAM), which determines where to focus. The combined effect allows the backbone to suppress clutter while selectively amplifying discriminative features of small or densely packed components.

Given an intermediate feature map , CAM first computes two channel descriptors by spatial global pooling:

where both outputs are of shape .

These descriptors are then passed through a shared two-layer MLP with reduction ratio r:

where with and . The channel attention map is obtained via and is used to refine the feature via channel-wise reweighting:

This operation enhances channels describing component contours, solder interfaces, and material boundaries, while suppressing channels dominated by background textures or repeated silkscreen fonts.

The channel-refined feature is then processed by SAM to generate a spatial attention map that highlights the exact pixel regions corresponding to true component areas. SAM computes channel-wise average and max pooling:

resulting in two feature maps of size , which are concatenated and passed through a convolution to obtain the spatial attention map:

Finally, the spatial attention map reweights the feature spatially:

SAM ensures that the model focuses on true device contours and pin boundaries while deemphasizing visually similar but irrelevant structures such as copper traces immediately adjacent to components.

2.2.2. BiFPN-Based Multi-Scale Fusion with Tiny-Object Branch

To address the extreme scale variation of PCB components—from sub-millimeter resistors to large integrated circuits—the neck architecture is enhanced using a Bi-Directional Feature Pyramid Network (BiFPN) together with an additional 16× downsampled tiny-object detection branch. The tiny-object branch preserves high-resolution spatial details that would otherwise vanish in deeper layers, ensuring that components smaller than pixels remain detectable by subsequent fusion layers. After building this high-resolution branch, feature maps across all scales are fused using a BiFPN structure that introduces learnable weights to adaptively balance contributions from different resolutions.

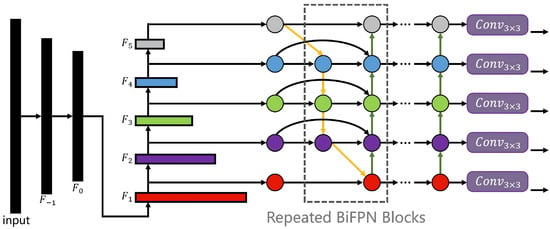

As shown in Figure 2, in BiFPN, each fused feature node receives multiple inputs , each representing a feature tensor from either a top-down or bottom-up pathway. Instead of naively summing these inputs, BiFPN computes a normalized weighted fusion:

where are learnable scalar importance weights (enforced via ReLU to keep them non-negative) and is a small constant to prevent division by zero. This normalization ensures stable gradient flow and allows the model to learn which scales are more relevant for a given PCB component type. After the normalized fusion, each output node is refined using a convolution:

Figure 2.

Architecture of the Bi-Directional Feature Pyramid Network (BiFPN), illustrating repeated top-down and bottom-up feature fusion with learnable weighted connections and depthwise separable convolutions for efficient multi-scale representation.

To realize bi-directionality, each scale repeats this process twice, i.e., once during the top-down pathway and once during the bottom-up pathway. The repeated bi-directional passes allow the fused features to integrate both semantic information from deeper layers and fine-grained spatial detail from shallow layers, which is an essential capability for PCB inspection scenarios, where small SMD devices lie adjacent to large ICs and the background contains high-frequency patterns such as silkscreen and copper traces.

Through this mechanism, the network learns scale-adaptive fusion patterns: for large ICs, deeper semantic layers receive larger weights; for small resistors or capacitors, the high-resolution 16× branch dominates the fusion. This adaptive and learnable cross-scale aggregation significantly boosts tiny-object recall and stabilizes detection performance across diverse PCB layouts.

2.2.3. Pose-Aware Decoupled Detection Head and Composite Loss

To enable the detector to output not only axis-aligned bounding boxes but also component pose information, the proposed model employs a pose-aware decoupled detection head in which the classification and regression tasks are optimized through separate branches. This design avoids mutual interference between heterogeneous objectives and improves convergence stability in dense PCB scenes.

The regression loss integrates two components: a bounding-box alignment term using Complete-IoU loss and a vertex-offset supervision term based on distance. Specifically, the CIoU loss for the predicted box B and the ground-truth box is defined as:

where is the Euclidean distance between the box centers, d is the diagonal length of the smallest enclosing box of B and , v measures the aspect-ratio consistency, which is defined as , and is a balancing factor.

To enable the network to predict the full oriented geometry of each PCB component, we extend the YOLOv11 regression head to output four corner-vertex offsets in addition to the axis-aligned bounding box. For each detected instance with predicted box

where and denote the center coordinates of the bounding box, and and denote its width and height, the network predicts four 2D offset vectors , each representing the displacement from the predicted center to one of the true corner vertices of the component. The absolute vertex coordinates are reconstructed as follows:

During training, each predicted offset is directly supervised using the ground-truth annotated vertex positions :

where denotes the ground-truth component center. This loss forces the detector to learn the true oriented quadrilateral of each component, rather than only approximating it with an axis-aligned box. The vertex offsets will then be used to generate an initial, rotation-aware polygon that serves as the starting pose estimate for sub-pixel geometric fitting, which will be further discussed in Section 2.3.

For the classification branch, the prediction p for the ground-truth label is optimized using Focal Loss, which mitigates the severe class imbalance typical in PCB datasets where some components (e.g., resistors) appear far more frequently than rare IC packages. The Focal Loss is defined as:

where is the focusing parameter that down-weights easy examples and enhances hard-sample learning, and balances positive and negative sample contributions. In practice, and provide stable gradients for small and sparse components.

The total loss is defined as follows:

where the balancing weights and are chosen to keep all three terms on comparable scales ( in our implementation). Since the vertex-offsets provide only an initial pose estimate for Stage 2, this term is weighted moderately to avoid overwhelming the CIoU box regression.

2.3. Fine Localization via Sub-Pixel Template Fitting

After obtaining coarse component predictions from the enhanced YOLOv11 detector, the final high-precision localization is performed through a constrained sub-pixel refinement process. For each detected device, the predicted bounding box serves as a Region of Interest (ROI), which restricts computation to a small, high-confidence spatial window.

To obtain a clean sub-pixel contour within the ROI, we first compute image gradients of the smoothed ROI using Sobel operators:

Adaptive Canny thresholds are set from gradient quantiles:

followed by non-maximum suppression to obtain a thin edge set E. For each edge pixel , we compute the unit normal:

and sample the intensity profile orthogonal to the edge:

Fitting a quadratic yields the closed-form sub-pixel displacement

The refined sub-pixel edge point is:

Collecting all refined points gives the final contour , which will be used in the least-squares fitting of Equation (22) to produce the final pose .

In the refinement stage, each PCB component is represented by a geometric template, defined as a small set of canonical vertices or boundary curves that describe the ideal shape of the component in a normalized coordinate frame. For rectangular ICs, the template consists of four corner points ; for connectors or specialized packages, additional structural points (e.g., pin-array reference vertices) may be included. The template does not encode absolute position or size; instead, it serves as a parametric shape that can be transformed by translation, rotation, and scale parameters to match the observed component in the image.

Before template optimization begins, the four corner vertices predicted by the enhanced YOLOv11 detector, which are given in Equation (11), are used to generate an initial, rotation-aware pose estimate. An initial similarity transform is obtained from:

This produces a coarse oriented template that already aligns closely with the actual component. Since the predicted vertices encode its approximate rotation and geometry, the initialization lies within a few pixels of the true contour.

The refined pose is then solved using the sub-pixel contour :

where is the closest point on the transformed template boundary. With as initialization, Gauss–Newton refinement converges rapidly to the final sub-pixel-accurate pose . This optimization yields refined estimates of the center, orientation angle, bounding contour, and, when applicable, the precise coordinates of key structural vertices or pin tips. Even when one or more structural vertices are not visible in the image, once the transformation is optimized using the available contour points, all template vertices—including those occluded or partially missing—can be mapped back into the image via the optimized transformation.

3. Results

3.1. Dataset and Experimental Setup

Experiments were conducted on the dedicated PCB-component dataset constructed in this study. The approximately 150,000 annotated component instances span 20 device categories, exhibiting a naturally imbalanced but realistic distribution consistent with industrial PCB manufacturing. Small passive components (e.g., 0201/0402 resistors and capacitors) dominate the dataset with approximately 65,000–75,000 instances due to their high density on most boards. Mid-sized components such as inductors, crystal oscillators, and compact connectors contribute 35,000–45,000 instances, while larger components—including QFP- and BGA-packaged ICs—account for 20,000–30,000 instances. Additionally, 30,000 instances include manually annotated corner-pin vertex coordinates to support the proposed vertex-offset regression branch.

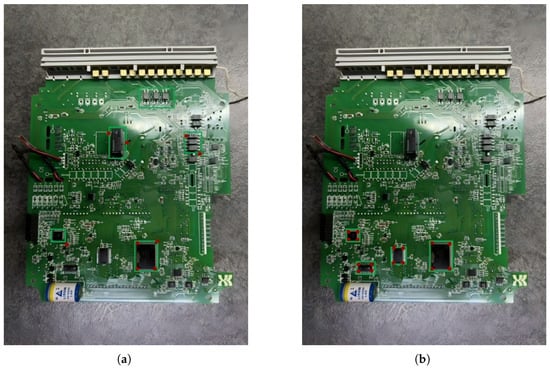

Unlike images captured in clean laboratory conditions, the PCBs in our collection were primarily sourced from industrial recycle stations, encompassing a wide spectrum of real-world degradation patterns. These boards include discarded industrial control modules, communication interface boards, power-control PCBs, and various embedded processing units. Due to prolonged use and uncontrolled storage, many boards exhibit mechanical warping, surface contamination, oxidation, scratches, and partial component damage. This diversity in board condition, combined with varied component densities and irregular backgrounds, provides a challenging testbed that better reflects realistic industrial inspection scenarios.

The dataset was divided into 80%/10%/10% for training, validation, and testing. To avoid any form of data leakage, the dataset is partitioned in a strictly board-wise manner: each physical PCB appears in only one of the train, validation, or test splits, ensuring that no image or crop from the same board is shared across subsets.

The YOLOv11-based detector is trained using the AdamW optimizer with an initial learning rate of , weight decay of , and momentum parameters . A cosine-annealing learning-rate schedule with a 5-epoch warm-up is applied over 300 epochs. Input images are resized to while preserving aspect ratio, followed by random cropping and multi-scale augmentation in the range [0.8, 1.2]. Non-maximum suppression (NMS) uses an IoU threshold of 0.65 and a confidence threshold of 0.25; during inference, class-agnostic NMS is applied unless otherwise noted. Models are trained with a batch size of 16 on a NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU.

3.2. Detection Performance

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed two-stage framework, we first analyze the detection accuracy obtained from the enhanced YOLOv11-based Stage 1 detector. Table 1 compares the baseline YOLOv11 model with several architectural variants, including attention-augmented backbones (SE, CBAM), BiFPN-based feature aggregation, and our full design incorporating a tiny-object detection branch and vertex-offset regression.

Table 1.

Overall detection accuracy (mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95) for baseline YOLOv11, ablation variants, and the proposed models.

The results show that both attention mechanisms (SE, CBAM) and feature aggregation improvements (BiFPN) individually contribute to higher detection accuracy. Combining CBAM with BiFPN yields a significant gain, indicating that attention-guided feature refinement and multi-scale fusion are complementary. Furthermore, the tiny-object branch provides a clear additional boost, particularly for fine-grained passive components (0201/0402 resistors and capacitors), ultimately allowing the full model to achieve 99.6% mAP@0.5 and 97.8% mAP@0.5:0.95.

To further analyze performance at different spatial scales, Table 2 reports AP@0.5 for small, medium, and large components. Small-object detection is critical for PCB inspection due to the prevalence of tiny passives and densely packed layouts.

Table 2.

Detection accuracy (AP@0.5) for small, medium, and large PCB components (COCO scale definitions).

The proposed detector achieves the highest scores across all scales, with a notable +14% improvement over the baseline for small components. This verifies that the tiny-object branch successfully enhances high-resolution feature representation and that CBAM–BiFPN coupling strengthens multi-scale feature extraction. Medium and large objects are already near saturation in baseline YOLOv11, but the proposed model offers consistent improvements.

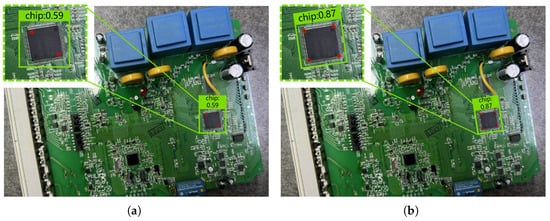

As shown in Figure 3, visual comparisons further reveal that the baseline YOLOv11 suffers from frequent missed detections for 0201/0402 resistors and small passive components, whereas the optimized network preserves their spatial details and confidently distinguishes them from visually similar background textures.

Figure 3.

Detection performance comparison between the baseline YOLOv11 and the proposed method. (a) Baseline YOLOv11 result, exhibiting two missed chips and one false detection. (b) The proposed framework, successfully detecting all key chips with no erroneous predictions.

3.3. Localization Accuracy

The proposed two-stage coarse-to-fine framework was evaluated on pin-level localization accuracy. Using the deep-learning output as the initial ROI, the final localization coordinates are yielded through the sub-pixel edge extraction and the following template-based least-squares geometric optimization. Figure 4 shows the result of localization.

Figure 4.

Localization comparison between the original YOLOv11 and the proposed framework. (a) Original YOLOv11, which predicts only two diagonal vertices with significant localization error. (b) The proposed framework, accurately predicting all four vertices of each chip, demonstrating superior localization precision over tradition methods especially when the objects are rotated.

The four configurations in Table 3 are constructed by toggling the two key components of the localization pipeline: (i) Vertex-Offset Initialization, which uses the predicted vertex offsets from Stage 1 to estimate an initial transformation via Equation (21), and (ii) Sub-pixel Refinement, which performs least-squares template fitting using sub-pixel contour points via Equation (22).

Table 3.

Ablation study on Vertex-Offset Initialization and Sub-pixel Refinement. Columns report: (1) mean center-point localization error (mm); (2) maximum vertex error across the four template corners (mm); (3) mean time needed to produce vertex coordinates (ms); and (4) failure rate, defined as the percentage of ROIs where the optimizer diverged or converged to a high-residual local minimum.

The Configuration (a) reflects the raw output of Stage 1 without any geometric post-processing. Because no template-based correction is applied, this configuration inherits all prediction errors from the detector and cannot recover missing or misaligned keypoints. This leads to the highest center and vertex errors, as well as a relatively high failure rate, demonstrating that direct regression alone is insufficient for reliable keypoint localization on complex PCB layouts.

Configuration (b) leverages the predicted vertex offsets to solve Equation (21) and estimate an oriented quadrilateral that better aligns with the underlying component. This reduces both center and vertex errors compared to the Configuration (a). However, without refinement, this configuration still relies on the quality of Stage 1 predictions: if the detector misses a keypoint or produces a biased offset, the resulting cannot correct it. This explains the moderate remaining errors and the observable failure cases.

In contrast, Configuration (c) improves accuracy dramatically because the refinement stage incorporates dense sub-pixel boundary points capable of reconstructing missing or noisy keypoints. However, poor initialization often places the optimizer outside the attraction basin of the true minimum, especially for rotated components or components with strong background clutter. This leads to longer convergence times, more local-minima traps, and a noticeably higher failure rate than in the full pipeline.

The full pipeline (d) yields the best performance across all metrics. Vertex-Offset Initialization provides a rotation-aware initialization that positions the template close to the true solution, while Sub-pixel Refinement delivers the fine-grained geometric correction necessary for sub-pixel accuracy. As a result, the optimizer converges faster, avoids poor basins of attraction, and achieves the lowest failure rate. The synergy between these two stages also leads to the smallest errors in both center and vertex localization, confirming that neither module alone is sufficient to achieve the desired level of precision.

4. Discussion

The experimental results confirm that the proposed coarse-to-fine framework effectively addresses the long-standing challenges of PCB component detection under strong background interference. The CBAM-enhanced backbone and BiFPN fusion significantly improve small-object discrimination by jointly suppressing the noise induced by silkscreen and trace, and by preserving multi-scale structural cues. This aligns with prior findings in attention-based object detection, yet the present study demonstrates that such mechanisms are particularly impactful in PCB imagery, where background textures often exceed components in visual saliency.

A key contribution of this work is the introduction of vertex-offset regression, which provides a compact pose-aware representation that bridges the gap between conventional bounding-box detectors and the precise rotational and structural requirements of automated PCB disassembly. Unlike prior approaches that output only axis-aligned or rotated boxes, the proposed vertex-supervised regression allows the detector to infer corner geometry and orientation cues, yielding a substantially improved initialization for the subsequent refinement stage. Importantly, the refinement module does not rely on the correctness or completeness of every predicted or annotated vertex. Because the template-fitting stage optimizes a global similarity transformation, all structural vertices—including those missing, severely occluded, or imperfectly annotated—are mapped back into the image once the optimal transformation is obtained. This ensures that the method remains robust even when certain vertices are not visible or when manual ground-truth labeling is noisy or inconsistent. The sub-pixel geometric fitting therefore demonstrates the complementary strengths of learning-based prediction and model-based optimization: the former supplies reliable coarse localization under challenging visual conditions, while the latter enforces global geometric coherence and delivers the fine-grained accuracy required for high-precision industrial manipulation.

Despite these advantages, several limitations must be acknowledged. The refinement stage depends on predefined template geometry and may struggle with unknown or highly irregular components. Localization may degrade under heavy occlusion or contamination, and the current pipeline assumes planar PCB surfaces without accounting for board warp or 3D variation. These limitations suggest promising avenues for future research, including learning-based sub-pixel regressors to replace template matching, multi-view or depth-assisted modeling to handle nonplanarity, meta-learning for rapid adaptation to unseen component types, and deeper integration with robotic execution for fully autonomous disassembly.

5. Conclusions

This work presents a high-precision PCB component recognition and localization framework that combines an optimized YOLOv11 detector with a sub-pixel geometric refinement stage. By integrating CBAM attention, multi-scale BiFPN fusion, and vertex-offset regression, the method effectively suppresses PCB background interference and captures component pose with high fidelity. Experiments demonstrate substantial gains in small-object detection and reliable sub-pixel localization accuracy, meeting the stringent requirements of industrial automated disassembly. The proposed approach offers a practical and efficient solution for precision PCB perception and provides a solid foundation for future extensions towards more general, adaptive, and fully autonomous industrial vision systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W.; methodology, L.W. and A.W.; software, L.O. and X.C.; validation, X.C.; formal analysis, L.O. and A.W.; investigation, H.W. and X.C.; writing—original draft, L.W.; writing—review and editing, K.Z.; visualization, H.W.; supervision, A.W.; project administration, K.Z.; funding acquisition, K.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was funded by the State Grid Zhejiang Electric Power Science and Technology Project (5211WF250006) Research on Key Component Reverse Disassembly Technology of Scrap Electric Energy Meter Circuit Boards Based on Embodied Intelligence.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Li Wang, Liu Ouyang, Huiying Weng, Xiang Chen, and Anna Wang were employed by State Grid Zhejiang Electric Power Co., Ltd. The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PCB | Printed Circuit Board |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| CBAM | Convolutional Block Attention Module |

| FPN | Feature Pyramid Network |

| BiFPN | Bi-Directional Feature Pyramid Network |

| IC | Integrated Circuit |

| R-CNN | Region-based Convolutional Neural Network |

| SSD | Single-Shot MultiBox Detector |

| DETR | Detection Transformer |

| SE | Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks |

| ViT | Vision Transformer |

| HRNet | High-Resolution Net |

| AOI | Automated Optical Inspection |

| SUSAN | Smallest Univalue Segment Assimilating Nucleus |

| QFP | Quad Flat Package |

| BGA | Ball Grid Array |

| CAM | Channel Attention Module |

| SAM | Spatial Attention Module |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| SMD | Surface-Mount Device |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| NMS | Non-Maximum Suppression |

References

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1506.01497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1506.02640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2016; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switherland, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollar, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollar, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. EfficientDet: Scalable and Efficient Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10778–10787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.12872. [Google Scholar]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.Y.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. Scaled-YOLOv4: Scaling Cross Stage Partial Network. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2011.08036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.06521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, I.; Zoph, B.; Vaswani, A.; Shlens, J.; Le, Q.V. Attention Augmented Convolutional Networks. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1904.09925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, H.; Deng, J. CornerNet: Detecting Objects as Paired Keypoints. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1808.01244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, D.; Krähenbühl, P. Objects as Points. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.07850. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sun, K.; Xiao, B.; Liu, D.; Wang, J. Deep High-Resolution Representation Learning for Human Pose Estimation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.09212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, A.; Yang, K.; Deng, J. Stacked Hourglass Networks for Human Pose Estimation. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1603.06937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Wei, P. A PCB Dataset for Defects Detection and Classification. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.08204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.K.; Kwon, B.K.; Park, J.H.; Kang, D.J. Machine Learning-Based Imaging System for Surface Defect Inspection. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 2016, 3, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Liu, S.; Zhao, D.; Tang, L.; Zou, W.; Zheng, B. PCB-YOLO: An Improved Detection Algorithm of PCB Surface Defects Based on YOLOv5. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Wan, F.; Lei, G.; Xu, L.; Ye, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhou, W.; Xu, C. EC-YOLO: Improved YOLOv7 Model for PCB Electronic Component Detection. Sensors 2024, 24, 4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.M.; Brady, J.M. SUSAN—A New Approach to Low Level Image Processing. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 1997, 23, 45–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canny, J. A Computational Approach to Edge Detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1986, PAMI-8, 679–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.; Matthews, I. Lucas–Kanade 20 Years On: A Unifying Framework. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 56, 221–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.