Abstract

In 2024, four papers that presented four different solution approaches for the knapsack problem with forfeits (KPF) appeared in the OR literature. However, none of these four solution approaches compared their performance to the other three on a standard set of 120 KPF test instances. In this short paper, both empirically and statistically, these four KPF solution approaches are compared. Furthermore, by using the solutions from the best method (HESM) among the four to initialize Gurobi, bounded solutions are obtained. For the 120 KPF test instances, this simple hybrid approach resulted in solutions that, on average, were guaranteed to be within 7% of the optimums. This type of guarantee does not exist for other KPF solution methods in the literature. It is very important for operations research (OR) practitioners that need to ensure the value of their solutions to management to have some guarantee of the quality of these solutions.

Keywords:

knapsack problems; soft conflict constraints (forfeits); test instances; metaheuristics; Gurobi; bounded solutions MSC:

90-08

1. Introduction and Background

In a 2020 paper [1], the knapsack problem with forfeits (KPF), which is an extension of the classic knapsack problem (KP), was introduced. In addition to maximizing profit of items inserted into the knapsack without exceeding the knapsack capacity, the KPF requires that pairs of items that are in conflict cannot both be inserted into the knapsack without a penalty. In other words, pairs of items that are “in conflict” can both be inserted into the knapsack provided a penalty is incurred. This is in contrast to the knapsack problem with conflicts (KPC), in which pairs of items that are in conflict cannot both be inserted into the knapsack [2]. In [1], 40 instances of the KPF are defined and a greedy algorithm (GA) and a carousel greedy (CG) [3] algorithm are used to solve these problems, with the CG outperforming the GA. In a 2022 paper [4], the first 80 additional instances of the KPF were defined. Of these 80 KPF instances, 40 were larger than the 40 defined in [1] and 40 had more forfeits than the 40 defined in [1]. This resulted in a set of 120 KPF instances that could be used for testing KPF solution methods. In [4], in addition to solving these 120 KPF instances with the GA and CG as in [1], a hybrid solution approach was defined that combined the CG with a genetic algorithm. This solution approach is referred to as GA-CG. In [4], by solving the 120 KPF instances, GA-CG outperformed both the GA and CG.

In 2024, four papers [5,6,7,8] that were published in four different OR journals presented four different solution approaches to the KPF. Vieira et al. [5] presented an approach that is referred to as ILS-VND that involves iterated local search, variable neighborhood descent, and tabu search. This heuristic takes into account four neighborhood structures and introduces an efficient data structure to explore these structures. Zhao and Hifi [6] presented an approach that is referred to as RL-DCSS that involves adaptive learning and scatter search exploration. The RL-DCSS algorithm iteratively generates and combines subsets using path-relinking followed by a two-stage improvement process. Jovanovic and Voss [7] presented an approach that is referred to as MFSS that involves using a fixed set search with integer programming to solve subproblems. A new ground set of elements for the KPF is used to augment the information provided by the fixed set. Additionally, the method for creating fixed sets is modified to increase solution diversity. Zhou et al. [8] presented an approach that is referred to as HESM that is a hybrid heuristic that combines evolutionary search with adaptive feasible and infeasible search. Additionally, HESM uses a streamlining technique to accelerate candidate solutions evaluation.

When tested on the 120 KPF instances presented in [4], all four of these 2024 papers demonstrated that their solution approaches outperform the greedy, CS, and GA-CG that were discussed in [4]. However, only the RL-DCSS [6] is compared to the MFSS [7] on the 120 KPF instances presented in [4]. Vieira et al. [5] do not compare their ILS-VND to RL-DCSS, MFSS, or HESM. Jovanovic and Voss [7] do not compare their MFSS to ILS-VND, RL-DCSS, or HESM. Zhou et al. [8] do not compare their HESM to ILS-VND, RL-DCSS, or MFSS. Hence, the purpose of this paper is twofold: (1) to empirically and statistically compare the performances of ILS-VND, RL-DCSS, MFSS, and HESM on the 120 KPF test instances discussed in [4], and (2) to demonstrate that by providing Gurobi with an initial heuristic KPF solution, Gurobi can generate bounded solutions in a timely manner. Hence, the lack of any efficient KPF solution procedures in the literature that provide guarantees on solution quality is addressed.

In the next section, a mathematical formulation for the KPF will be given. Then, the empirical performance of the four KPF solution approaches will be compared empirically using the 120 KPF instances discussed in [4]. This will be followed by a statistical analysis comparing the performance of these four KPF solution approaches on the 120 KPF test instances. Next, how using the best 2024 KPF solution approach as an initial solution for Gurobi results in the generation of bounded solutions for these test problems is discussed. Some observations will complete this paper.

2. Mathematical Formulation for the KPF

We now provide the mathematical formulation that was used in [5] for the KPF.

Let X be a set of available items, where pi and wi represent the value and weight of item i, respectively, for all . Let b be the maximum knapsack capacity, and F be the set of penalized pairs (i,j)k of size l, where i,j and dk are the penalty associated with pair (i,j)k.

Given these definitions, the KPF can be formulated as the following Integer Linear Programming (ILP) model:

The decision variables are binary, indicating whether each item i is inserted in the knapsack or not. Also, a set of binary variables vk is introduced to indicate whether each pair of items (i,j)k is selected or not. The objective function (1) maximizes the total value of the selected items minus the total penalty cost. Constraint (2) ensures that the weight capacity b is not exceeded. Constraint (3) ensures that for all penalized pairs (i,j)k, vk = 1 when items i and j are both part of the solution. Constraints (4) and (5) ensure that the variables are binary.

In the next section we will compare for the first time in the OR literature the four KPF solution methods published in 2024.

3. Comparison of the Four KPF Solution Methods Published in 2024

3.1. The 120 KPF Test Instances

In [1], 40 KPF instances (referred to as O(Original)) were defined such that the number of items n belongs to the set {500, 700, 800, 1000}. The number of forfeit pairs l is equal to 6n, and each of them is composed of a random pair of items. The capacity b is equal to 3n. The item weights, profits, and forfeit costs are randomly chosen integers in the intervals [3, …, 20], [5, …, 25], and [2, …, 15], respectively. For each value of n, 10 different instances were generated.

In [4], 40 LK (large knapsack) instances were generated corresponding to the set O instances but with a larger b value equal to 5n. Also, in [4], 40 MF (more forfeits) instances were generated with the same b values and the same number of items as set O. However, for each instance, there are now 8n new randomly generated forfeit pairs.

3.2. Empirical Comparison of the Four 2024 KPF Solution Methods on the 120 KPF Test Instances

It was noted previously that each of the four KPF solution methods published in 2024 outperformed the GA, CG, and GA-CG on the 120 KPF test problems. Hence, the comparison we are making here (which has not been performed before) is among the four 2024 KPF solution methods. Table 1 summarizes their average objective function values and number of best solutions obtained for each data set (O, LK, MF) and overall. All data is based on the detailed results reported in [5,6,7,8]. Each of these four KPF solution methods is stochastic in nature and we are using the best solution reported when each method is executed 10 times for each of the 120 KPF instances. The last column in this table is based on taking the best objective function value found for the four methods. In other words, these average objective function values represent executing each method 10 times, taking the best of the 10 runs, then taking the best of these four values, and finally taking the average over the 40 instances for the O, LK, and MF data sets, and the average over the 120 instances for the total.

Table 1.

Comparison of four knapsack problems with forfeits solution approaches published in 2024 (40 instances in each category: O, LK, MF).

We see from Table 1 that for the O data set, ILS-VND does not perform as well as the other three (RL-DCSS, MFSS, HESM) in both average objective function value and number of best solutions obtained. However, for the LK and MF data sets, the HESM outperforms the other three in both average objective function values and number of best solutions obtained. Overall, for all 120 instances, based on average objective function values, RL-DCSS and HESM are very close. However, HESM found the best solution 88 times (73%) and RL-DCSS found the best solution 61 times (51%). In the next section, the performance of these four solution methods on these 120 KPF test instances will be analyzed statistically.

4. Statistical Analysis of the Four KPF Solution Methods

We compared four KPF solution methods—ILS_VND, RL-DCSS, MFSS, and HESM—using 120 test instances from [4], focusing on their objective function values.

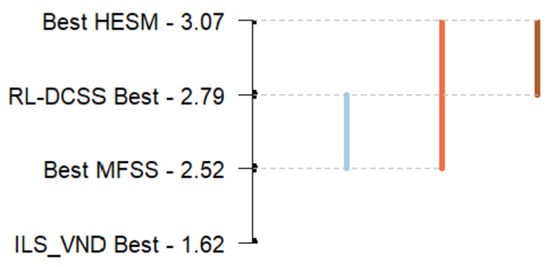

A Friedman test was performed to assess overall performance differences, as it is appropriate for related samples (Song et al., 2025 [9]). The test revealed highly significant differences among the methods (p = 0.0000; see Figure 1). A post hoc Nemenyi test at the 5% significance level was then conducted to identify which pairs are different significantly while controlling for multiple comparisons (Song et al., 2025 [9]).

Figure 1.

Friedman test and post hoc Nemenyi test of four solution methods. Average ranks are shown. The Friedman test indicates statistically significant differences among the methods (p < 0.001), with a critical distance of 0.428 at the 5% significance level.

Figure 1 shows the ranks of the four methods, where higher ranks correspond to better performance. A critical distance of 0.4282 was applied: when the difference in ranks between two methods is smaller than this threshold, their performance is considered statistically indistinguishable; when it equals or exceeds the threshold, the difference is statistically significant.

The resulting groups are as follows:

- Group 1: HESM and RL-DCSS (represented by the purple and upper orange bars), which achieved the highest ranks.

- Group 2: RL-DCSS and MFSS (lower orange and blue bars).

- Group 3: ILS_VND, which ranked lowest. The overlap of RL-DCSS in both Group 1 and Group 2 is normal in the Nemenyi test results; it indicates that RL-DCSS serves as a statistical bridge between the two groups—its performance is not significantly different from either HESM or MFSS.

Overall, HESM significantly outperformed MFSS and ILS_VND, while its performance was statistically indistinguishable from RL-DCSS.

5. Gurobi Analyses

Of the four KPF solution methods published in 2024, we have shown empirically that HESM [8] performed the best on 120 KPF test instances in terms of both average objective function values and the greatest number of best solutions, with RL-DCSS [6] a close second (see Table 1). Furthermore, we showed statistically that HESM [8] significantly outperformed MFSS [8] and ILS-VND [5], while its performance was statistically indistinguishable from RL-DCSS [6]. However, none of these four KPF solution methods guarantee that optimums have been found or that the solutions generated are guaranteed to be close to the optimums.

In this section, using Gurobi (12.0.3) on a standard computer, we show that by providing Gurobi with the HESM solution as a starting point, Gurobi is capable of generating either guaranteed optimums (data set O) or solutions that are guaranteed to be close to the optimums (data sets O, LK, MF) in reasonable computing times. The mipgap = [best upper bound—best current solution]/(best current solution) is a measure of how close the current solution is to the optimum. Note that once the mipgap is less than 0.01%, the best solution generated is reported as optimum and Gurobi terminates.

In Table 2, although the best Gurobi solutions found are only slightly better than the starting HESM solutions, Gurobi does provide important bounds on its solutions. Specifically, the average mipgaps are 2%, 10%, and 10% for data sets O, LK, and MF, respectively. In order to try to reduce the execution time, we decided to execute Gurobi in an iterative manner, periodically increasing the acceptable mipgap for Gurobi termination. This iterative approach is referred to in the OR literature as the simple sequential increasing tolerance (SSIT) strategy. In Table 2, the SSIT results show that the execution times can be reduced significantly with only a small increase in mipgap values. Hence, by providing Gurobi with an initial HESM solution, Gurobi used in either a default mode or in an iterative manner can generate solutions that are bounded close to the optimums. This is not true for any of the KPF solutions that currently appear in the literature. Finally, by having Gurobi start with the best HESM solution, for the same Gurobi execution time, the average mipgap is reduced by 9% compared to cold-starting Gurobi.

Table 2.

Default Gurobi versus SSIT strategy both warm-started with HESM.

6. Summary

In 2024, four different solution approaches for the knapsack problem with forfeits (KPF)—ILS-VND, RL-DCSS, MFSS, and HESM—were published in the operations research literature, but their performance was not compared to a common benchmark. This paper provides the first empirical and statistical comparison of these four methods using the standard set of 120 KPF test instances. The results show that HESM achieved the highest average objective function values and the greatest number of best solutions, with RL-DCSS performing as a close second; statistical analysis using the Friedman test with a follow-up Nemenyi test indicates that HESM significantly outperformed MFSS and ILS-VND, while its performance was statistically indistinguishable from RL-DCSS. Furthermore, by using the HESM solutions to warm-start the commercial solver Gurobi, the solver was able to produce either proven optimal solutions or solutions with guaranteed optimality gaps for all 120 test instances within reasonable computation times, with an average guarantee of being within approximately 7% of the optimum. Within the scope of the solution methods and benchmark instances examined in this study, this warm-started hybrid approach provides solution quality guarantees that are not available from the standalone KPF solution methods currently reported in the literature.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, P.C., Y.L., M.S.S. and F.J.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cerulli, R.; D’Ambrosio, C.; Raiconi, A.; Vitale, G. The Knapsack Problem with Forfeits. In Proceedings of the Combinatorial Optimization: 6th International Symposium, ISCO 2020, Montreal, QC, Canada, 4–6 May 2020; Revised Selected Papers. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coniglio, S.; Furini, F.; San Segundo, P. A new combinatorial branch-and-bound algorithm for the Knapsack Problem with Conflicts. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 289, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrone, C.; Cerulli, R.; Golden, B. Carousel greedy: A generalized greedy algorithm with applications in optimization. Comput. Oper. Res. 2017, 85, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capobianco, G.; D’Ambrosio, C.; Pavone, L.; Raiconi, A.; Vitale, G.; Sebastiano, F. A hybrid metaheuristic for the knapsack problem with forfeits. Soft Comput. 2022, 26, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.M.; Nogueira, B.; Pinheiro, R.G.S. An integrated ILS-VND strategy for solving the knapsack problem with forfeits. J. Heuristics 2024, 30, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Hifi, M. A reinforcement learning-driven cooperative scatter search for the knapsack problem with forfeits. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 198, 110713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, R.; Voss, S. Fixed set search matheuristic applied to the knapsack problem with forfeits. Comput. Oper. Res. 2024, 168, 106685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Hao, J.K.; Jiang, Z.Z.; Wu, Q. Adaptive feasible and infeasible evolutionary search for the knapsack problem with forfeits. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2024, 32, 1442–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.S.; Lu, Y.; Rando, D.; Vasko, F.J. Statistical Analyses of Solution Methods for the Multiple-Choice Knapsack Problem with Setups: Implications for OR Practitioners. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 262, 125622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.