Abstract

The increasing global demand for cleaner transportation has intensified the importance of efficient AdBlue® (AUS32) production, a key chemical in selective catalytic reduction (SCR) systems that reduces nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions from diesel engines. This work presents a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation study of the urea–water mixing process within a high shear mixer (HSM), aiming to enhance the sustainability of AdBlue® manufacturing. The model evaluates the hydrodynamic characteristics critical to optimising the dissolution of urea pellets in deionised water, which conventionally requires significant preheating. Experimental validation was conducted by comparing pressure drop simulation results with operational data from an active industrial facility in the United Kingdom. Therefore, this study validates the CFD model against an industrial two-stage Rotor–stator under real operating conditions. The computational framework combines a refined mesh with the k-ω SST turbulent model to resolve flow structures and capture near-wall effects and shear stress transport in complex flow domains. The results reveal opportunities for process optimisation, particularly in reducing thermal energy input without compromising solubility, thus offering a more sustainable pathway for AdBlue® production. The main contribution of this work is to close existing gaps in industrial practice and propose and computationally validate strategies to improve the numerical design of HSM for solid dissolution.

MSC:

76D17; 76F25; 76M50

1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, the exponential growth of industrialisation and modernisation has introduced a range of environmental and societal challenges, including an increase in pollution levels, depletion of natural resources, urban overpopulation, and the progressive desertification of rural regions. Among these, air pollution has emerged as a primary concern, increasing attention from international regulatory and public health organisations due to its impact on human health and environmental sustainability. Recognised by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as a significant environmental health risk, air pollution contributes to approximately 7 million premature deaths annually worldwide [1].

Noorimotlagh et al. [2] define air pollution as the presence of a mixture of several types of substances, including: (i) gases such as carbon monoxide (CO), ground-level ozone (O3), nitrogen oxides—NOx = NO + NO2—and sulfur oxides (SOx), among others; (ii) solids such as particulate matter (PM) with different aerodynamic diameters, especially coarse particles (PM10), fine particles (PM2.5), ultrafine particles (PM1), and nanoparticles (PM0.1); (iii) volatile metals such as zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), and lead (Pb); and (iv) volatile organic compounds (VOC), such as bioaerosols and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). In general, air pollutants comprise a broad range of substances, including greenhouse gases (GHGs), particulate matter and ozone.

The transport sector is the second-largest contributor to GHGs emissions in Europe, following the energy sector, with road transport accounting for about 20% of total emissions [3]. Among transport-related emissions, nitrogen oxides are particularly critical due to their adverse environmental and health effects. NOx compounds are predominantly emitted from anthropogenic combustion sources, notably transportation (46%), agriculture (20%), power generation (10%), industry and residential heating (each contributing approximately 5%) [4,5]. NOx emissions are precursors to the formation of ground-level ozone and photochemical smog and are associated with acidification of soil and water bodies, contributing to biodiversity loss [6]. Epidemiological studies have also linked long-term exposure to NOx with increased incidences of cardiovascular diseases, ischemic stroke, chronic respiratory conditions, and neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease [2,7].

In response to the growing evidence on the harmful effects of NOx, regulatory authorities, particularly within the European Union, have introduced increasingly stringent emission standards [8]. To comply with these regulations, automotive manufacturers have adopted a suite of exhaust aftertreatment technologies, including the Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) system, which has demonstrated NOx removal efficiencies of up to 96% under optimal operating conditions [9,10,11,12].

The Urea-SCR technology is currently the dominant solution in the automotive market and is based on ammonia-SCR technology [13]. SCR technology reduces NOx emissions by injecting a reductant, commonly ammonia, into the exhaust stream, where it reacts with NOx in the presence of a catalyst to produce nitrogen and water [14]. Due to ammonia’s corrosive nature and associated safety risks, direct storage on board vehicles is unfeasible [15]. Consequently, ammonia is supplied in the form of an aqueous urea solution (AUS32), commercially known as AdBlue®, a registered trademark of the German Association of the Automotive Industry (VDA). AdBlue® comprises 32.5% ± 0.7 (w/w) high-purity urea and 67.5% ± 0.7 (w/w) deionised water [16]. This solution suffers thermolysis and hydrolysis when dosed and injected into the diesel exhaust gas (DEG) stream [14].

AdBlue® is produced by dissolving solid urea in high-purity deionised water. Given that water constitutes over two-thirds of the final solution, its purity is essential. This is achieved using advanced water treatment methods such as distillation, deionisation, ultrafiltration, or reverse osmosis [16].

In this industry, there are two main mixing processes for the production of AdBlue®: the traditional method based on a stirred tank and the in-line production method [17]. Although the chemical process is identical in both approaches, the in-line production method has become predominant due to its greater versatility.

The traditional method, also known as batch production, involves the discrete mixing of a predetermined amount of urea (NH2CONH2) with a specific volume of deionised water in a stirred tank. The major disadvantages of this method are: (i) the limitation in the volume of solution produced, which cannot exceed the total volume of the mixing tank; and (ii) the requirement for the solvent to be at a high temperature to accelerate dissolution.

The in-line (continuous) production method is a more flexible and scalable approach where raw materials are continuously fed, and product output is only constrained by the availability of inputs and storage capacity. High shear mixers (HSMs) are commonly used to ensure effective and efficient dissolution, even at lower solvent temperatures [18].

High-shear mixers, also referred to as rotor–stator (RS) mixers, are among the most advanced mixing devices used in applications requiring intense dispersion, emulsification, and deagglomeration [18]. An HSM typically consists of a high-speed rotor operating at 500–25,000 rpm within proximity (100–3000 µm) to a fixed stator [19]. This configuration generates intense shear fields and turbulent flows that facilitate fast particle size reduction through mechanisms such as: (i) erosion, when a larger agglomerate is fragmented, leading to a progressive reduction in its size; (ii) rupture, when the large agglomerate is broken into smaller agglomerates, but all of the same size, this process is repeated until the smallest agglomerate size is obtained; and (iii) shattering, when large agglomerates are broken directly into very small pieces, without the existence of a passage through intermediate agglomerate size [20].

Mixing operations can be carried out either in batch or continuous mode. In batch mixing, the components are introduced into a vessel and agitated for a defined period until the desired degree of homogeneity is achieved. This cyclic operation can result in longer processing times and variability between batches. In contrast, continuous (in-line) mixing is performed under controlled conditions, where streams of raw materials are continuously fed at controlled flow rates and mixed. The mixing efficiency is determined by flow dynamics, mixer geometry and impeller speed [21]. Continuous mixing offers advantages such as reduced residence time, improved process control, and consistent product quality, making it particularly suitable for large-scale and high-throughput applications [18,22]. The devices utilise rotors with tailored geometries to promote shear and turbulence, which are critical for homogenization and deagglomeration. Optimization parameters include rotor speed, number and height of rotor teeth, shear gap, and blade inclination [18,23,24].

In the analysis of mixing quality reported by Gong et al. [23], high homogeneity of the final solution is achieved by using high blade/rotor speeds, with the number of blades significantly influencing the kinetics of mixing into granules. In another study by Liu et al. [24], the performance of the HSM mixer can be increased by increasing the rotor speed, the number and height of the rotor teeth, and reducing the spacing between the rotor and the stator, also known as shear gap. The inclination of the rotor teeth also influences the efficiency of the RS set, and in this study, the use of vertical teeth is recommended. This geometry improves material deagglomeration, given the high turbulent dissipation energy generated in the stator. Ming et al. investigate the effect of stator geometry on the performance of continuous high-shear mixers [21]. Experiments have shown that slot width, area, and angle affect both flow rate and power consumption. Increasing the slot width improves the flow rate while reducing power consumption, whereas enlarging the slot area raises both the flow rate and energy use.

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has emerged as a valuable tool for studying and optimising the complex flow behaviour within rotor–stator systems. CFD enables the detailed analysis of velocity fields, turbulence structures, and the shear stress distributions that are otherwise difficult to measure experimentally due to the opaque and highly dynamic nature of these systems [17]. By resolving local flow phenomena, CFD supports the design of more efficient mixer geometries and the refinement of operating parameters, thereby enhancing process performance and sustainability.

Recent advances in turbulence modelling, mesh refinement techniques, and computational resources have improved the predictive accuracy of CFD models applied to HSMs. For instance, the Multiple Reference Frame (MRF) and Sliding Mesh (SM) methods, which provide steady-state and transient representations of rotor motion, respectively, have been used to simulate rotor–stator interactions [25,26]. The accuracy of these simulations largely depends on the choice of turbulence model. Among the commonly employed models, the k–ε, k–ω SST, and Reynolds Stress Model (RSM) have demonstrated the ability to predict turbulent energy dissipation and shear stress transport in complex flow domains. Table 1 presents a comparison of turbulence models used in CFD simulations of HSMs.

Table 1.

Comparison of standard turbulence models used in CFD simulations of rotor–stator high shear mixers (HSMs).

For industrial-scale HSM simulations, the k–ω SST model typically offers the optimal balance between computational efficiency and predictive accuracy, particularly in capturing near-wall and interfacial shear regions. The Reynolds Stress Model (RSM) is recommended for detailed validation or design investigations where turbulence anisotropy has a significant impact on mixing behaviour. Meanwhile, standard or RNG k–ε models remain valuable for rapid, process-scale simulations and preliminary design optimisation.

Despite these advances, challenges remain in bridging the gap between laboratory-scale simulations and industrial-scale operations. Scale-up is often hindered by the nonlinear relationship between shear rate, flow regime, and mixing efficiency [17]. Therefore, validating CFD models with experimental or plant-scale data is essential to ensure that numerical predictions accurately reflect real operational behaviour. In the context of AdBlue® production, such validation is critical to support process optimisation efforts aimed at reducing thermal energy consumption while maintaining solubility and product quality.

To evaluate and optimize the hydrodynamic performance of the HSM employed in AdBlue® production, a three-phase numerical simulation approach was adopted: (i) Phase I: CFD simulation of the first rotor–stator (RS) assembly; (ii) Phase II: Simulation of the second RS assembly to investigate interactive hydrodynamic effects and (iii) Phase III: In situ measurements of flow, temperature, and mixing variables within the operating HSM used in commercial AdBlue® production.

These simulations provide insights into flow dynamics and mixing homogeneity, which are critical for improving process efficiency and ensuring consistent AdBlue® quality. The CFD models are validated using an industrial case study of AdBlue® production, supporting their application in the design and optimisation of HSM units.

2. CFD Simulation of an HSM

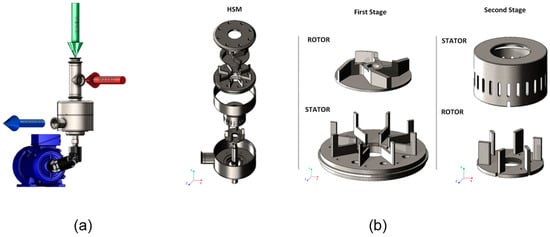

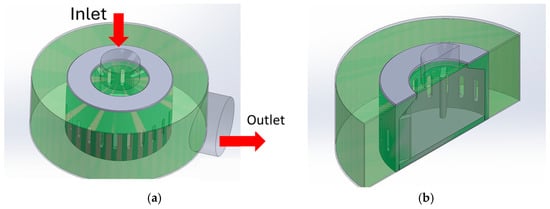

The HSM used to carry out CFD simulations is based on an industrial vertical high-shear mixer composed of two separate RS and feed assemblies. Urea is fed by gravity along the vertical axis. The water is fed using a hydraulic pump in the axial direction. Figure 1a shows the overall 3D design of this equipment. The production process is conducted in two stages. Each stage consists of a rotor–stator assembly. Each of the rotors is fixed to the transmission shaft-driven shaft. This shaft is located in the geometric center of the mixer and connects to the shaft of an electric motor, a motor shaft using two flexible cardan couplings. The 3D geometries of the HSM were developed using SolidWorks® 2022 software and are presented in Figure 1b.

Figure 1.

(a) Representation of the feed inlets (green—urea; red—water) and outlet represented in blue (AdBlue®). (b) Detailed view of the HSM: (i) view of the two stages; (ii) rotor–stator assembly of the first stage; (iii) rotor–stator assembly of the second stage.

The first stage of the HSM is responsible for premixing. The solid urea particles combine with the previously heated deionised water. At this stage, a 4-bladed polygonal rotor, together with an 8-bladed stator, disperses the urea and water, forming a slurry that is directed to the next stage. In this second stage, this slurry, in which the urea is partly dissolved and partly suspended, is again subjected to dispersion and shearing by the second set of RS. The 6-blade rotor is encapsulated in a cylindrical diffuser stator with 24 openings. This assembly leads to the complete disintegration of the solid structure of the urea particles suspended in the water, which should result in a completely homogeneous solution of AdBlue® at the outlet of the volute. The rotor–stator mixer presents a highly complex geometry, characterised by narrow gaps, detailed features, and strong shear regions that require a fine mesh to correctly resolve the local flow structures. Performing a full-domain simulation with the necessary level of refinement would result in an extremely large mesh, leading to prohibitively high computational costs and impractically long runtimes. To maintain numerical accuracy while ensuring the simulations remained computationally feasible, the CFD analysis was therefore split into two sections. This approach enabled the mesh to be kept sufficiently refined in each region of interest without exceeding available computational resources.

The geometric properties of each part of the HSM are presented in detail in Supplementary Information.

2.1. First Stage of HSM

2.1.1. Geometric Modeling

The 3D geometries of the RS assemblies of the HSM were developed using SolidWorks® 2022 software and are presented in Figure 1b. For the phase I, Rotor and Stator assembly are spaced 4 mm apart.

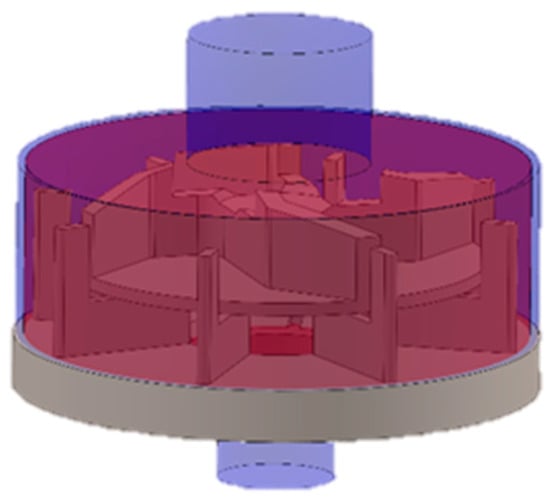

Both geometries were enclosed within static cavities, which define the flow domain boundaries around the agitators/rotors. The first flow boundary of the RS assembly is represented by a red cylinder; this domain corresponds to the internal volume where the fluid is in motion. The total flow domain of the first RS assembly is represented by three vertically stacked cylinders. Each of these cylinders represents, respectively: (i) the inlet region; (ii) the fluid contact with the RS assembly; and (iii) the outlet. Both fluid domains of this RS assembly are intrinsically connected. This relationship is clearly illustrated in Figure 2, which shows the complete domain of the first stage of the HSM.

Figure 2.

Fluid flow domain of RS phase I. The grey regions represent the solid components, and the translucent areas represent the fluid zones.

Table 2 presents the dimensions of the components of the first stage of the HSM.

Table 2.

Geometric properties of the first-stage parts.

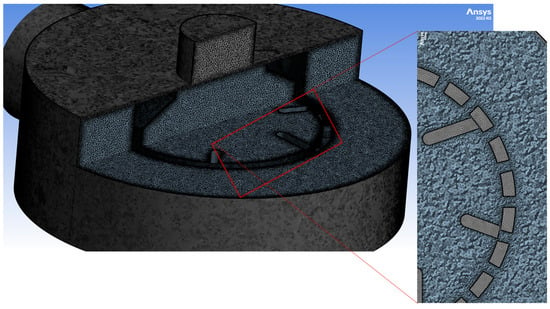

2.1.2. Domain Discretisation

In this case study, the mesh was generated automatically and refined several times until it met the following convergence criteria, which are the values of: (i) maximum dimensionless wall distance—Max Wall y+; (ii) maximum wall shear stress; and (iii) the area-weighted average of static pressure.

Seventeen meshes were generated and refined during Phase I. Simulations included linear, quadratic, and automatic meshes, mostly with hexahedral elements (hexadominant) combined with tetrahedral elements (tetrahedron), using mixed cell geometries (multizone), with and without cell-space refinements (inflation, face sizing), etc. These simulations involved meshes ranging from 565,000 cells up to a maximum of 35 million cells. Table 3 presents the mesh refinements carried out during Phase I.

Table 3.

List of results from the 15 simulations performed in Phase I.

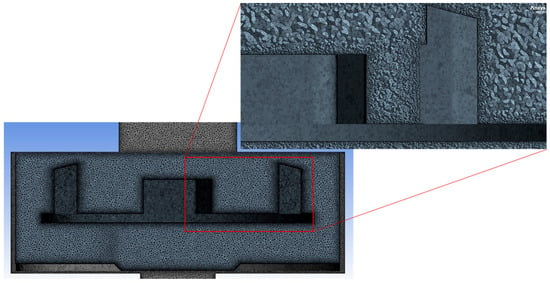

In Figure 3, a section view of mesh No. 13 is shown.

Figure 3.

Section view on the YZ plane of mesh No. 13 with a close-up on rotor walls.

2.1.3. Flow Simulations of RS 1st Stage

CFD simulations were carried out to investigate the fluid flow characteristics within the domain, incorporating turbulence modelling to capture the effects of rotational motion and wall interactions, using the ANSYS Fluent 2022 R2 solver. The simulations were carried out in a desktop workstation equipped with AMD Ryzen Model, 12 cores, 3.7 GHz and a RAM 432 GB, DDR4 3600 MHz CL18.

The flow field is governed by the continuity and Navier–Stokes equations, which describe mass and momentum conservation, respectively. The continuity equation (for an incompressible Newtonian fluid) is given by:

where the velocity in the direction, which is decomposed into the mean () and fluctuating () components ().

Conservation of momentum in an inertial reference frame is described by:

where is the density, is the velocity, is the static pressure, is the viscous stress tensor, is the Reynolds stress tensor and is the gravitation acceleration.

To solve turbulence effects, the k–ω Shear Stress Transport (SST) model was employed. This two-equation turbulence model is known for its effectiveness in capturing near-wall behaviour and flow separation under adverse pressure gradients, making it especially suitable for rotating equipment and internal flow systems. The SST formulation blends the standard k–ω model near walls with the k–ε model in the free stream, enhancing robustness and accuracy. Therefore, the turbulence kinetic energy (k) and turbulence dissipation rate (ω) equations of k–ω model SST were solve. The turbulence kinetic energy, , was obtained from the following transport equation:

where represents the generation of turbulent kinetic energy due to mean velocity gradients, is the effective diffusivity of k, and is the dissipation of k due to turbulence.

And the turbulence dissipation rate (ω) is given by:

represents the generation of , represents the effective diffusivity of , is the effective diffusivity of , and is the dissipation of due to turbulence. The effective diffusivity for is given by:

where is the turbulent viscosity, and is the turbulent Prandtl number for . On the other hand, the effective diffusivity for ω can be expressed as:

is the turbulent Prandtl number for .

The and , which are the terms that accounts for production of turbulence kinetic energy and turbulence dissipation rate, are given by Equations (7) and (8), respectively:

where S is the modulus of the mean rate-of-strain tensor, and are model coefficients and is the turbulent (eddy) kinematic viscosity.

Regarding the dissipation terms, and are described as:

where and are model coefficents.

In turbulent flows, the near-wall region plays a critical role, mainly where high velocity gradients and wall shear stresses occur. The behaviour of the flow in this region has been extensively studied, and Theodore Von Kármán (1930) described how the velocity distribution near walls follows a logarithmic behaviour relative to the distance from the wall [29]. Based on this, Ludwieg and Tillmann (1950) and other researchers developed dimensionless parameters used to characterise the flow near solid boundaries [30], such as the wall distance parameter , defined as:

where is the distance from the wall, is the friction velocity and represents the kinematic viscosity.

The wall shear stress can be solved using the following equation:

where is the wall shear stress [31].

The value determines how well the CFD model solves the viscous sublayer near the wall. In this study, the mesh was refined in wall-adjacent regions to ensure that the first node from the wall lies within the viscous sublayer ( < 1). This approach avoids reliance on empirical wall functions. It enables the k–ω SST model to solve the boundary layer directly, which improves the accuracy of simulations in regions with strong wall effects and turbulent shear. These considerations were particularly important for the rotor–stator configuration analysed in this work, where wall shear stresses, separation, and flow curvature play a dominant role in the fluid dynamics of the system.

The area-weighted average static pressure was calculated to obtain a representative surface value. This average is defined as the integral of the static pressure over the surface, normalised by the total surface area. In discrete form, it can be expressed as:

where denotes the static pressure at facet i, is the corresponding facet area, and A is the total surface area. This approach ensures that the contribution of each facet is weighted according to its area, providing a physically meaningful measure of the average pressure across the surface.

2.1.4. Boundary Conditions

The boundary conditions remained the same in all simulations performed. The computational simulations were conducted using a pressure-based and a steady-state solver. The modelled flow is incompressible.

The working fluid is set as water at 20 °C, and the following physical properties were retained: a density (ρ) of 998.2 kg m−3 and a dynamic viscosity (μ) of 10−3 Pa.s. At the inlet, a velocity of 1.53 m s−1 was specified, corresponding to the operating conditions of an industrial AdBlue® production facility. The outlet was defined with a constant pressure boundary condition set to atmospheric pressure.

The domain was divided into two primary fluid zones. The first is assigned to the water-liquid material. A rotational frame of reference was applied, with the rotation axis defined along -axis, producing motion in the -direction within the plane -plane. The second zone, also assigned to water-liquid, shares the same rotation axis direction as the first zone.

The wall conditions were configured with the rotor defined as a moving wall, where rotational motion was applied along -axis. The rotor operated at an angular speed of 400 revolutions per minute (RPM). In contrast, the stator was treated as a stationary wall with a no-slip condition, representing a fixed boundary.

2.1.5. Numerical Schemes

A coupled pressure-velocity solver was selected for improved convergence performance. A second-order upwind scheme was set to solve momentum equations, turbulent kinetic energy (k) and specific dissipation rate (ω). The pressure equations were solved using a second-order spatial discretisation scheme, and for the gradient, a least-squares cell-based scheme was employed. The Global Pseudo Time Step method was adopted to stabilise the solution process during the steady-state computation.

To promote convergence while maintaining solution stability, the following under-relaxation factors were applied: 0.5 for pressure and momentum, 0.75 for turbulent kinetic energy and specific dissipation rate and 1.0 for density, body forces and turbulent viscosity.

For the convergence criteria, residuals were defined as 10−3 for all the equations.

2.1.6. Results Analysis of RS 1st Stage

Within the scope of the CFD analysis of the first RS assembly, a total of 15 meshes were simulated using the same boundary conditions and initial values. Only the mesh type and configuration were changed, with the primary objective of determining the best mesh topology and the corresponding number of cells.

Table 2 presents the results obtained, focusing on the three parameters of interest: (i) Max Wall y+; (ii) Max Wall Shear; and (iii) area-weighted average of static pressure.

A quick analysis of the results in Table 2 enables the identification of meshes No. 2, 3, 4, and 6 as non-convergent, since their respective values of Max Wall y+, Max Wall Shear, and Area-Weighted Average are disproportionate compared to the others. These meshes produce unstable solutions with irregular residuals. On the other hand, all the remaining meshes resulted in stable solutions.

Analysing Wall y+ as the convergence factor in Table 2, it is noted that refining to meshes denser than No. 13 causes little change in the Wall y+ value despite the increase in the number of mesh cells. This mesh enables the flow simulation to converge, presenting the optimal balance between the number of cells, the Wall y+ value, and processing time. This mesh was selected for the evaluation of the RS first-stage results.

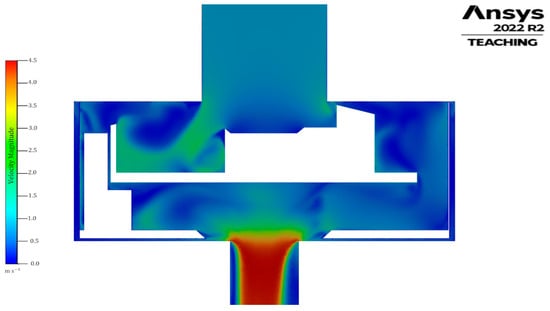

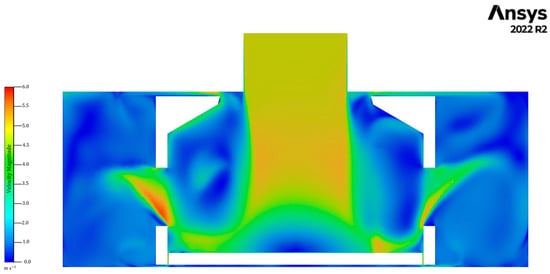

Figure 4 shows the scalar velocity magnitude map of the RS assembly with the encapsulation, displayed as a cross-sectional view in the YZ plane at = 45 mm. The fluid is propelled by the rotor blades, creating a low-pressure zone in the tube located at the upper axial position. A high-velocity region forms at the suction of the inlet tube. There is a transfer of momentum from the rotor to the fluid, which is verified by the pressure difference between the inlet and the outlet. For AdBlue production, these hydrodynamic features are beneficial because the high-velocity jet and associated shear layers promote large velocity gradients, i.e., shear stresses, that induce urea pellets breakage and accelerate dissolution, enhance mixing, and prevent local saturation or crystal formation. The low-pressure region further promotes the transport of fresh solution into the high-shear zone, ensuring continuous renewal of the fluid processed by the rotor. These mechanisms support a faster and more homogeneous AdBlue production, improving batch quality and reducing mixing time.

Figure 4.

Contours of the scalar velocity magnitude of the RS assembly with the casing, shown in a cut view on the YZ plane at x = 45 mm.

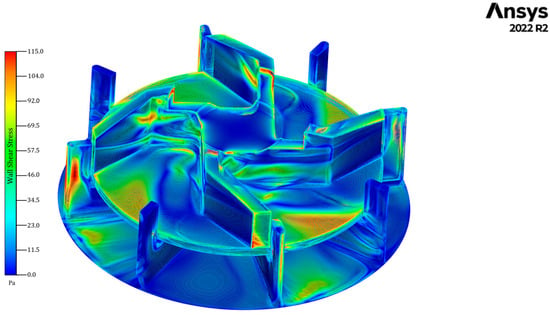

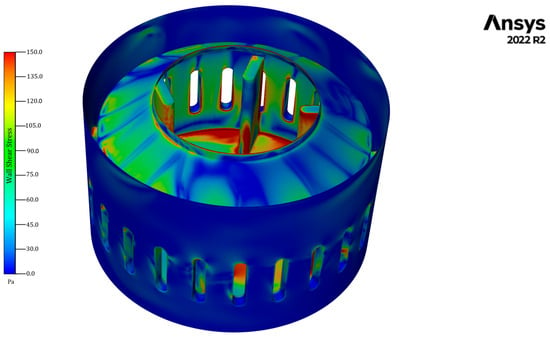

In Figure 5 and Figure 6, the contours of Wall Shear Stress and Wall y+ on the rotor and stator walls are displayed, respectively. The distribution of the highest shear stress zones does not follow a defined pattern and is scattered across the rotor head. The tips of the rotor blades and the stator baffles near the rotor blades exhibit higher wall shear stress values. The Wall y+ stress has a similar distribution and is shown in Figure 6. This spatially localised shear concentration is consistent with the operating principles of high-shear mixers. These regions correspond to areas where the fluid is subjected to larger velocity gradients, directly contributing to turbulence production and the breakdown of urea pellets and homogenisation of concentration gradients during urea dissolution. Therefore, the observed shear distribution is a key mechanism through which the RS promotes rapid mixing and enhances AdBlue homogeneity.

Figure 5.

Wall Shear Stress contours of the RS 1st stage.

Figure 6.

Wall y+ contours of the RS 1st stage.

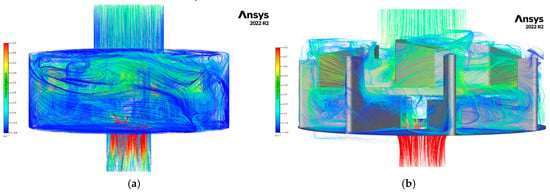

This analysis culminated in the generation of flow pathlines for the scalar velocity in the RS assembly. Figure 7a shows the flow trajectories colored according to the magnitude of the scalar velocity in the assembly, i.e., wall, rotor, stator, inlet, and outlet. Figure 7b incorporates the visual elements of the rotor and stator into Figure 7a, removing the wall to improve graphical representation and facilitate understanding. The velocity trajectories indicate a highly three-dimensional and unsteady topology characterised by zones of separation and reattachment, strong recirculation pockets near the stator and rotational structures induced by the rotor’s motion.

Figure 7.

Scalar velocity pathlines in the entire RS assembly in (a) the fluid domain and (b) with the rotor and stator visible.

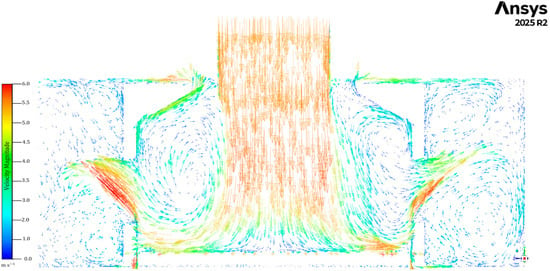

In summary, Figure 8 presents the pathlines of the scalar velocity in the YZ plane at = 45 mm of this assembly. The images with the trajectories show the complex nature of the flow, with zones of separation, flow recirculation, and vortices. These complex patterns are integrated within the main flow direction described previously, with the fluid entering, then separating around the rotor, and converging toward the outlet, accompanied by rotational movements induced by the rotor. The recirculation patterns are advantageous in AdBlue production, as they increase high-shear zones and promote repeated exposure of the urea–water mixture to regions with high turbulent kinetic energy.

Figure 8.

Scalar velocity pathlines in the RS assembly viewed at the YZ plane at x = 45 mm.

After analysing the data obtained for mesh No. 13, it is possible to observe that the velocity of the mixture flow accelerates as it moves through the RS assembly in the downward direction along the -axis. The average inlet velocity is 2.0 m/s. At the outlet, this velocity increases to approximately 4.49 m/s. This increase in kinetic energy is compatible with the expected performance of a rotor–stator system and is directly linked to the shear generation responsible for promoting rapid dissolution.

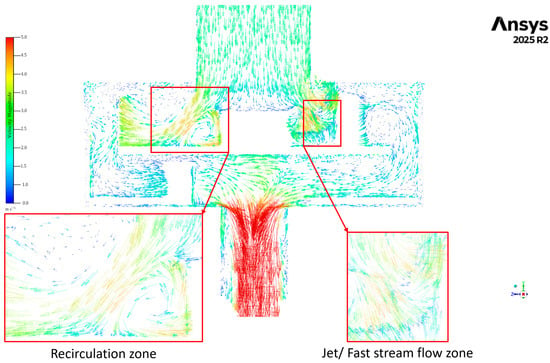

Examining the results in the YZ plane cut view at = 70 mm, it is possible to identify fast stream flow and recirculation zones. The jet formation zones are located near the rotor walls, while the recirculation zones occur near the stator blades. Figure 9 shows detailed views of these jets and the vortices formed by them near the mixer walls. These are also the zones with the highest values of turbulence, Wall y+, and Wall Shear Stress. For this process, where rapid mass transfer between urea particles and water is required, these zones play a crucial role in accelerating dissolution and ensuring uniform concentration distribution.

Figure 9.

Vector Map of jet and recirculation zones in the cut view on the YZ plane at x = 70 mm.

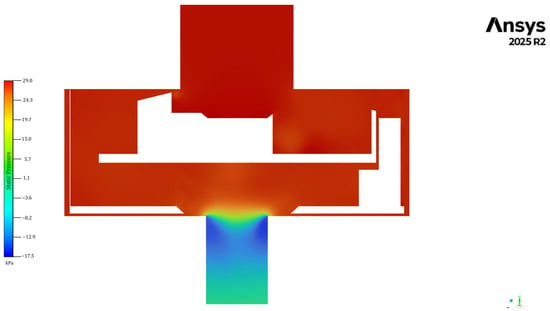

Figure 10 presents the static pressure contours of the RS assembly. The pressure field clearly shows a low-pressure region immediately on the bottom of rotor–stator and a higher-pressure zone within the surrounding stator–casing volume. This pressure gradient is a direct result of the momentum transfer from the rotating blades to the fluid and is a key driver of the internal circulation pattern. The low-pressure region promotes continuous entrainment of fresh urea solution into the rotor–stator gap, while the elevated pressure inside the casing supports strong radial discharge through the stator openings. Together, these mechanisms enhance the renewal of fluid within the high-shear zone, accelerate mixing, and reduce dead-flow regions. From a process standpoint, this pressure-driven transport is beneficial for AdBlue® production: it ensures faster homogenization of the urea–water mixture, supports more homogeneous concentration distribution, and contributes to shortening the overall mixing time required to achieve specification-compliant solution quality.

Figure 10.

Contours of the static pressure of the RS assembly, shown in a cut view on the YZ plane at x = 45 mm.

In summary, the results indicate that the RS first-stage assembly generates a complex, turbulence-rich flow pattern that combines shear-driven mixing, vortex-induced recirculation, and jet-impingement dynamics. These hydrodynamic mechanisms are essential for achieving efficient urea dissolution at controlled operating temperatures and directly support the applicability of the high-shear rotor–stator design in AdBlue® manufacturing.

2.2. Second Stage of HSM

2.2.1. Geometric Model

Following the same procedure as in the first stage, in the second phase, the rotor and stator were also encapsulated in moulds to create the respective boundaries of the flow domain. Figure 1b presents the geometry of the RS assembly of the second stage, and Figure 11 illustrates the moulds used to define the corresponding boundaries of the fluid domain.

Figure 11.

Rotor and stator of the second stage encapsulated in a representative mould of the total fluid flow domain, (a) view A and (b) view B.

Table 4 presents the geometric properties of the rotor, stator, and casing of the second stage. The Inner represents the fluid domain at this stage, i.e., it represents the free space between the solid parts where the fluid moves within the stage.

Table 4.

Geometric properties of the second stage parts.

2.2.2. Mesh Definition

In this phase, the mesh was generated automatically and refined multiple times until it met the previously established convergence criteria. Here, only nine meshes were generated and refined. The criteria and methodologies were kept the same as those used for the first stage RS simulations. These simulations involved meshes consisting of 2 million cells up to a maximum of 31 million cells. Table 5 presents the refinement levels of the meshes simulated during Phase II.

Table 5.

List of results from the 9 simulations performed in Phase II.

Figure 12 presents the geometry in the views of the two previous planes (YZ and ZX). This figure aims to provide a clearer visual representation of the negative moulds created and their respective domain boundaries.

Figure 12.

Mesh of Phase II RS assembly. Cut view in both planes—YZ and ZX.

2.2.3. Flow Simulations of RS 2nd Stage

As in Phase I, turbulence was modelled using the two-equation k–ω SST (Shear Stress Transport) model. The solved equations are described in Section 2.1.3.

2.2.4. Boundary Conditions and Initial Values

The boundary conditions established were kept constant across all 9 simulations performed. Only the mesh was modified through refinement. The computational simulations were carried out using the ANSYS Fluent 2022 R2 solver, employing a pressure-based, steady-state solution approach. The materials and boundaries were similar to those defined in phase I. The output results from the first stage simulation were subsequently used as initial conditions for the simulation of the second stage. Thus, a velocity boundary condition of 4.49 m/s was applied at the inlet, while the outlet was assigned a pressure boundary condition equal to atmospheric pressure.

Furthermore, the numerical schemes and discretisation were the same as those used in Phase I. For the convergence criteria, residuals were defined as 10−3 for all the equations.

2.2.5. Results Analysis of RS 2nd Stage

The CFD analysis of the second RS set, referred to as Phase II, was based on the simulation of a total of 9 meshes under the same boundary conditions and initial values. As in the Phase I procedure, a quick review of Table 5 confirms that all simulated meshes produced stable solutions based on the three parameters of interest: (i) Max Wall y+; (ii) Max Wall Shear; and (iii) area-weighted average static pressure.

Using the maximum Wall y+ as the convergence criterion, it is evident that Mesh No. 24 is the mesh of interest for the intended simulation. This is due to the variation in the maximum dimensionless wall distance that remains small as the number of iterations increases. Therefore, all relevant data for this work can be extracted based on Mesh No. 24, which also has a reduced simulation time compared to the others. These were the main reasons for selecting this mesh for Phase II.

The results observed for Mesh 24 in static pressure and Wall Shear Stress are attributed to its refined boundary layer discretization. This mesh includes four times more boundary layers than the others, allowing a higher resolution of near-wall velocity gradients and viscous effects. As a result, the static pressure is locally higher, and the Wall Shear Stress is lower, providing a more accurate representation of the near-wall flow. These features make Mesh 24 the most suitable choice for simulating phase II, where wall effects play a critical role.

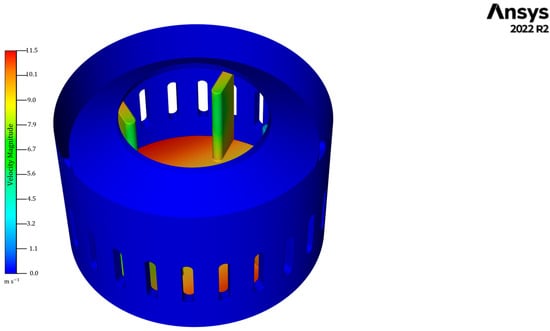

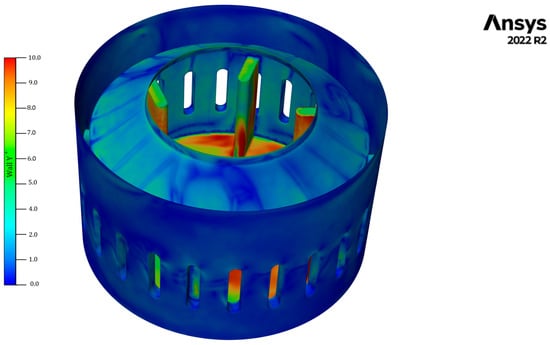

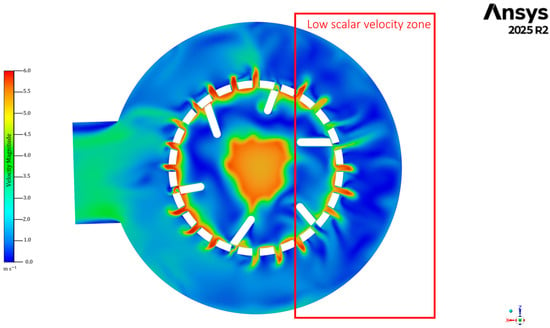

Similar to Phase I, Figure 13 and Figure 14 present the contours of scalar velocity (velocity magnitude) in the RS assembly under the previously described conditions.

Figure 13.

Scalar velocity contours of the RS 2nd stage.

Figure 14.

Scalar velocity contours of the RS assembly with a cut view on the YZ plane at x = 34 mm.

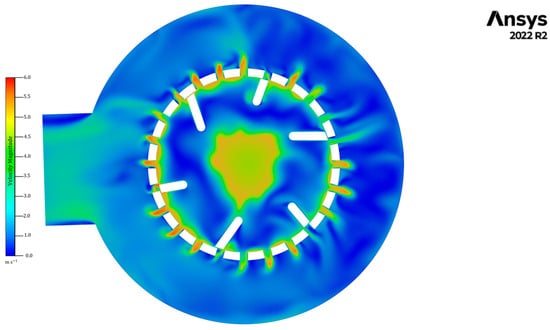

Figure 15 presents the scalar velocity in the RS assembly with the casing, showing a cross-sectional view of the ZX plane at = 65 mm.

Figure 15.

Scalar velocity contours of the RS assembly in the cut view on the ZX plane at y = 65 mm.

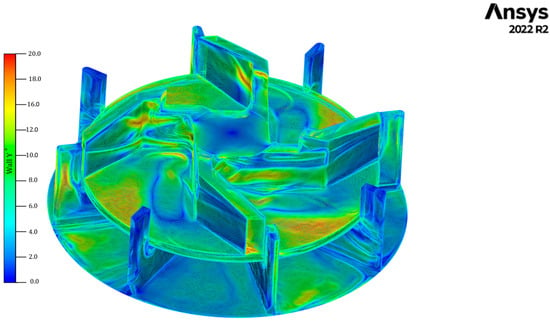

Figure 16 and Figure 17 present the contours of Wall Shear Stress and Wall y+ on the rotor and stator, respectively.

Figure 16.

Wall Shear Stress contours of the RS 2nd stage.

Figure 17.

Wall y+ contours of the RS 2nd stage.

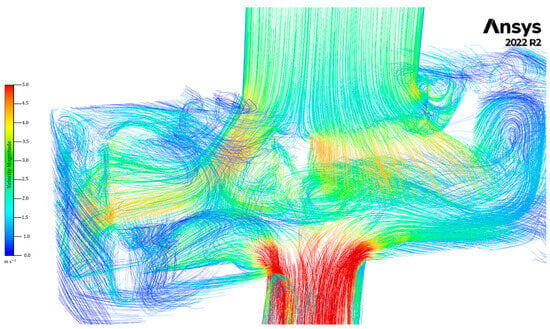

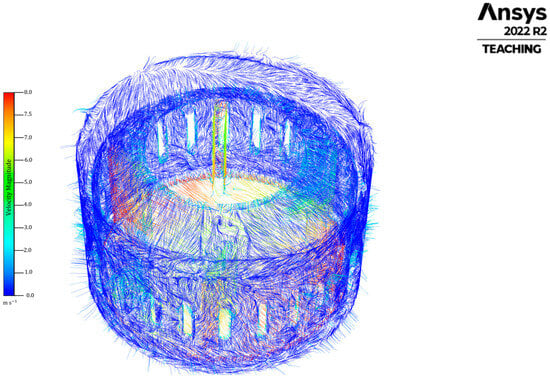

This analysis culminated in the generation of pathlines of the velocity magnitude for the RS assembly. Figure 18 shows the pathlines of the velocity magnitude in the assembly.

Figure 18.

Scalar velocity pathlines in the RS assembly.

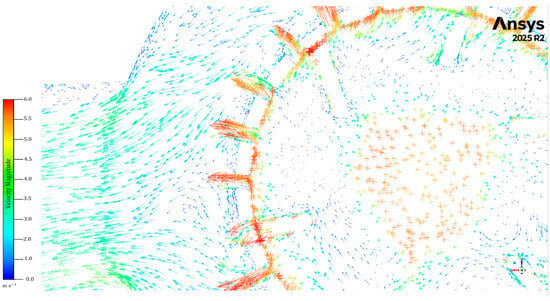

Analysing the data obtained for mesh No. 24, it is possible to observe in the YZ plane cut view at = 34 mm, an acceleration of the mixture in the clearance zone and the openings of the stator—Figure 19.

Figure 19.

Mixing acceleration zone (velocity vector map) in the cross-sectional view on the YZ plane at x = 34 mm.

In the annulus region, a deceleration of the flow can be observed. The initial velocity magnitude was set at 3.5 m/s, with the velocity at the outlet ranging between approximately 0.3 m/s near the walls and about 2.4 m/s in between (Figure 20). However, the greatest velocity deceleration is located in the annulus region opposite the volute (i.e., the outlet).

Figure 20.

Mixing deceleration zone (velocity vector map) at the outlet in the view of the ZX plane at y = 65 mm.

Similar to the results obtained in Phase I, the predominant jet zones are located near the rotor walls (Figure 21). Contrary to Phase I, the predominant circulation zones are located in the annulus region. According to the previous Phase I results, both zones correspond to the highest values of turbulence Wall y+ and Wall Shear Stress. These effects are generated by the rotor’s rotational forces around the y-axis. As with the Phase I results, the zones of highest velocity magnitude coincide with the zones of highest turbulence, as well as Wall y+ and Wall Shear Stress.

Figure 21.

Velocity contours of the mixture in the annulus in the view of the ZX plane at y = 65 mm.

The identified high-velocity jets and recirculation zones are directly beneficial for urea dissolution and homogenization. The acceleration zones and associated shear near the rotor walls enhance mass transfer and prevent local supersaturation, while the annular recirculation regions promote mixing uniformity across the bulk of the tank, supporting consistent quality in AdBlue production.

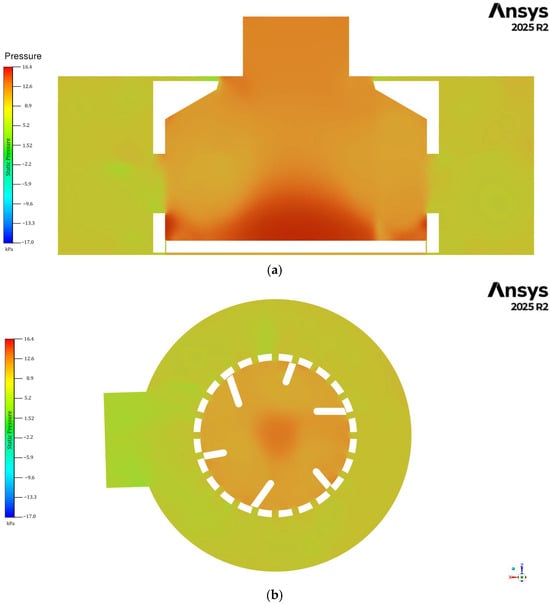

Figure 22 shows the static pressure contours within the second-stage rotor–stator (RS) assembly. As expected for this stage of the mixer, the pressure field exhibits a pronounced increase in the vicinity of the rotor–stator interface, where the flow is forced through the narrow blade passages. The central region displays elevated static pressure (orange–red tones), indicating flow deceleration and controlled compression before the fluid progresses to the downstream channels. The surrounding annular region shows lower pressure levels, reflecting the acceleration induced by the casing geometry and the RS rotation.

Figure 22.

Contours of the static pressure of the RS assembly with the casing, shown in a cut view on (a) the YZ plane at = 34 mm and (b) the ZX plane at y = 65 mm.

These pressure characteristics are directly relevant for AdBlue (preparation and conditioning prior to injection. The second-stage RS is responsible for refining the mixture homogeneity and stabilizing the pressure. A sufficiently elevated and uniform static pressure helps maintain continuous UWS delivery and reduces cavitation risk. Furthermore, regions with smooth pressure gradients minimize internal recirculation zones where urea deposits can form. Overall, the contours confirm that the second-stage RS provides the necessary pressure stability and mixing intensity for reliable AdBlue production.

3. Experimental Validation

Operational data were obtained from an HSM employed in AdBlue® production at an industrial facility located in the United Kingdom and used to analyse and validate all the simulation work described previously. The in situ data collected refer to AdBlue® production using a High Shear Mixer (HSM) coupled to a 2-pole synchronous electric motor operating at 50 Hz, with a maximum rotational speed of 2955 rpm. For the production batch highlighted in this comparison, the setpoint on the electric motor speed controller was 55% of maximum, corresponding to an approximate rotational speed of 1625 rpm. The inlet flow rate was measured using a vortex-type flow meter and recorded as 11.95 m3/h, approximately 1.53 m/s. These initial values were used as boundary conditions for the fluid flow simulation of the first stage of the HSM. The output results from the first-stage simulation were used as initial conditions for the second-stage simulation.

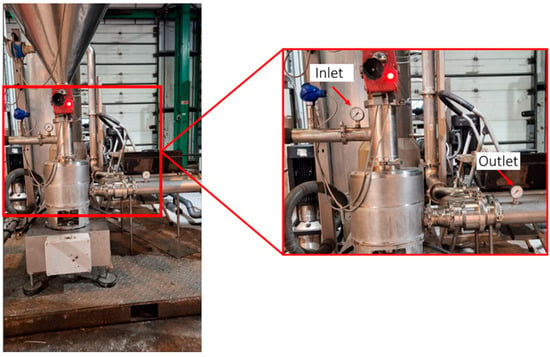

3.1. In Situ Survey

Key parameters of the HSM, as displayed in Figure 23, were recorded during continuous AdBlue production.

Figure 23.

Two-stage HSMs used for in-line AdBlue® production in service in the United Kingdom.

Several key parameters collected were, namely: rotational speed of the HSM, temperature of deionised water at the HSM inlet, temperature of the mixture at the HSM outlet, flow rate of deionised water at the inlet, flow rate of the mixture at the outlet, pressure at the HSM inlet, and pressure at the HSM outlet. Table 6 presents the survey of the data obtained.

Table 6.

In situ data collected from the HSM in England, United Kingdom, during weeks 43 to 50 of 2023.

The results demonstrate good reproducibility in terms of pressure drop. The data presented in Table 6 encompass all the required characteristics for validating the numerical model used in this study. Model validation was performed by comparing the experimental results (specifically the second experiment, conducted with a water velocity equal to the inlet velocity of the CFD simulation) with the simulation outcomes.

3.2. Model Validation—ΔpT

As previously discussed, the numerical simulations were performed using mesh No. 13 for the first stage and mesh No. 26 for the second stage, with a rotor speed of 400. Therefore, to mimic the experimental conditions, a new simulation was conducted for both stages, corresponding to a rotor speed of 1625 rpm. The boundary conditions in both cases remained unchanged.

For the first stage, the initial values were set equal to the actual on-site measurements. In contrast, the second stage simulation used as its initial conditions the results obtained at the outlet of the first stage.

The pressure values collected in situ were obtained directly from the pressure gauges installed on the inlet and outlet pipes of the HSM. These gauges are positioned at a height above the ground reference, shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Values of the manometric heights relative to the reference of the pressure gauges of the in situ HSM.

Figure 24 schematically shows the arrangement of the HSM pressure gauges.

Figure 24.

Position of the pressure gauges on the inlet and outlet piping of the in situ HSM.

The validation of the simulation results against real data collected in situ was performed based on the pressure difference.

In both datasets, recorded and simulated, the pressures measured and numerically obtained were converted into total pressures using Bernoulli’s equation:

where is the static pressure, is the hydrostatic pressure resulting from the product of the fluid density (), gravitational force (), and fluid height (); (iii) the dynamic pressure of the fluid, where is the fluid’s volumetric mass density and is the squared velocity; and (iv) is the total pressure value in bar.

Table 8 shows the same ΔpT value for both cases presented and studied here. This agreement confirms and validates the numerical simulation work presented here, thus endorsing the numerical methodology adopted.

Table 8.

Comparison of differential pressure values between the in situ HSM and the numerical simulation.

At the conclusion of both simulations, the total pressure at the outlet of the second stage was subtracted from the total pressure at the inlet of the first stage. This total pressure differential (∆pT) was then compared with the in situ pressure differential observed on the manometers during the measurements. The analysis of the results can be regarded as conclusive. In both cases, the total pressure differential (∆pT) was found to be −0.28 Bar under identical operating conditions.

Therefore, this study validates the CFD model using an industrial HSM configuration under real operating conditions, ensuring that the numerical approach accurately reflects the practical process behaviour. The computational setup incorporates a refined mesh to adequately resolve the flow structures, together with the k–ω SST turbulent model, which provides reliable predictions of near-wall behaviour and shear stress transport in complex flow domains. Wall functions are applied to efficiently capture boundary layer effects, striking a balance between computational cost and accuracy. This combination enables a robust representation of turbulent mixing phenomena, thereby consolidating the model’s relevance for the design and optimisation of industrial-scale AdBlue production systems.

4. Conclusions

This work presents a CFD-based hydrodynamic analysis of a High Shear Mixer used in the continuous production of AdBlue®. The study focused on a dual rotor–stator configuration, with simulations carried out in three phases to evaluate the performance of each RS assembly and the system as a whole. The CFD results demonstrated that the HSM generates high shear and turbulent energy dissipation, which are fundamental for achieving fast and homogeneous dissolution of urea in deionised water.

The numerical results provide a reliable basis for design optimisation and process improvement in industrial AdBlue® production, as the model was experimentally validated using pressure drop measurements, confirming its predictive accuracy under operational conditions. The validated model enables the assessment of key process parameters, including rotor speed, temperature, and flow rates, and their impact on mixing efficiency.

Therefore, this study enhances our understanding of the complex hydrodynamics in high shear mixing systems and offers a framework for designing and optimising industrial mixing processes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/math13244027/s1, Figure S1: Dimensions of the Rotor of RS Phase I; Figure S2: Dimensions of the Stator of RS Phase I; Figure S3: Dimensions of the Rotor of RS Phase II; Figure S4: Dimensions of the Stator of RS Phase II.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.J.S. and A.M.S.C.; methodology, L.F.A., A.M.S.C. and R.J.S.; validation, L.F.A., I.S.O.B., A.M.S.C. and R.J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.F.A. and I.S.O.B.; writing—review and editing, I.S.O.B., A.M.S.C. and R.J.S.; supervision, A.M.S.C. and R.J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P./MCTES through national funds: LSRE-LCM, UID/50020/2025; and ALiCE, LA/P/0045/2020 (DOI: 10.54499/LA/P/0045/2020).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Mr. Ludovic F. Ascenção was employed by the company Navistokes Engineering Lda. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Buruiana, D.L.; Sachelarie, A.; Butnaru, C.; Ghisman, V. Important Contributions to Reducing Nitrogen Oxide Emissions from Internal Combustion Engines. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noorimotlagh, Z.; Azizi, M.; Pan, H.F.; Mami, S.; Mirzaee, S.A. Association between air pollution and Multiple Sclerosis: A systematic review. Environ. Res. 2021, 196, 110386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Driscoll, R.; Stettler, M.E.J.; Molden, N.; Oxley, T.; ApSimon, H.M. Real world CO2 and NOx emissions from 149 Euro 5 and 6 diesel, gasoline and hybrid passenger cars. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 621, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, H.; Feng, X.; Fu, T.-M.; Wang, Y. NOx Emission Reduction and Recovery during COVID-19 in East China. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zheng, W.; Wang, Q. Effects of hydrogen peroxide, sodium carbonate, and ethanol additives on the urea-based SNCR process. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 772, 145551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baia, L.V.; de Araujo, L.R.R.; Pereira, C.G.; de Souza, W.C.; de Figueiredo, M.A.G. Adsorption as alternative process in the preliminary production of automotive additive. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Q. 2020, 26, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Luo, X.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Han, M.; Qie, R.; Wu, X.; Liu, D.; et al. Long-term association of ambient air pollution and hypertension in adults and in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 796, 148620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Khaled, A.; Khaled-El Feki, A.E.F.B. Distributed Real-Time Simulation of Numerical Models: Application to Power-Train; Université Grenoble Alpes: Saint-Martin-d’Hères, France, 2014; pp. 1–184.

- Latha, H.S.; Prakash, K.V.; Veerangouda, M.; Maski, D.; Ramappa, K.T. A Review on SCR System for NOx Reduction in Diesel Engine. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2019, 8, 1553–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ximinis, J.; Massaguer, A.; Pujol, T.; Massaguer, E. Nox emissions reduction analysis in a diesel Euro VI Heavy Duty vehicle using a thermoelectric generator and an exhaust heater. Fuel 2021, 301, 121029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de França, H.H.; da Silva, N.C.; Honorato, F.A. Evaluation of diesel exhaust fluid (DEF) using near-infrared spectroscopy and multivariate calibration. Microchem. J. 2019, 150, 104155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrabie, V.; Scarpete, D.; Zbarcea, O. The new exhaust aftertreatment system for reducing NOx emissions of diesel engines: Lean NOx trap (LNT). A study. Sci. Proc. XXIV Int. Sci.-Tech. Conf. Trans MOTAUTO 16 2016, 1, 110–113. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Z.; Li, S.; Guo, X.; Long, W. Research status and development trend of Urea-SCR technology. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Mechatronics, Materials, Chemistry and Computer Engineering (ICMMCCE 2015), Xi’an, China, 12–13 December 2015; pp. 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Tischer, S.; Bornhorst, M.; Amsler, J.; Schoch, G.; Deutschmann, O. Thermodynamics and reaction mechanism of urea decomposition. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 16785–16797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondzic, J.; Sremacki, M.; Popov, S.; Mihajlovic, I.; Vujic, B.; Petrovic, M. Exposure to hazmat road accidents—Toxic release simulation and GIS-based assessment method. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 293, 112941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 22241-1:2019; Diesel Engines—NOx Reduction Agent AUS 32, 1—Exigences de Qualité. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–14.

- Mortensen, H.H.; Arlov, D.; Innings, F.; Håkansson, A. A validation of commonly used CFD methods applied to rotor stator mixers using PIV measurements of fluid velocity and turbulence. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2018, 177, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konz, A.K.; Windhab, E. Experimental and computational study of a high speed pin mixer via PEPT, visualization and CFD. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2016, 155, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, W.; Guo, J.; Li, W.; Wang, B.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J. Effects of rotor and stator geometry on dissolution process and power consumption in jet-flow high shear mixers. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2020, 15, 384–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, S.; Li, W. High shear mixers: A review of typical applications and studies on power draw, flow pattern, energy dissipation and transfer properties. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2012, 57–58, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, M.; Wang, H.; Yang, X.; Wang, D.; Yuang, F.; Yu, W.; Du, J. The Impact of Stator Geometric Design on the Power Consumption in Continuous High-Shear Mixers. J. Food Process Eng. 2025, 48, e70194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, T.P.; Panesar, J.S.; Kowalski, A.; Rodgers, T.L.; Fonte, C.P. Linking power and flow in rotor-stator mixers. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 207, 504–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.; Zuo, Z.; Xie, G.; Lu, H.; Zhang, J. Numerical simulation of wet particle flows in an intensive mixer. Powder Technol. 2019, 346, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, J.; Li, W.; Yang, X.; Li, W.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, J. Comparison and estimation on deagglomeration performance of batch high shear mixers for nanoparticle suspensions. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 429, 132420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Zheng, K.; He, J.; Xiong, Y.; Tian, Z.; Lin, Y.; Long, D. Turbulent CFD Simulation of Two Rotor-Stator Agitators for High Homogeneity and Liquid Level Stability in Stirred Tank. Materials 2022, 15, 8563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utomo, A.T.; Baker, M.; Pacek, A.W. Flow pattern, periodicity and energy dissipation in a batch rotor–stator mixer. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2008, 86, 1397–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utomo, A.; Baker, M.; Pacek, A.W. The effect of stator geometry on the flow pattern and energy dissipation rate in a rotor–stator mixer. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2009, 87, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi, A.; Nilsson, H. Detailed numerical investigation of a Kaplan turbine with rotor-stator interaction using turbulence-resolving simulations. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2017, 63, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Karman, T. Mechanische Ahnlichkeit and Turbulenz. In Nachrichten der Akademie der Wissenschaften Gottingen; Göttingen Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Göttingen, Germany, 1930; pp. 58–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwieg, H.; Tillmann, W. Investigation of the Wall-Shearing Stress in Turbulent Boundary Layers; Technical Memorandum 1285; National Advisory Committee For Aeronautics: Hampton, VA, USA, 1950; p. 26.

- Nascimento, E.L. Suspensão e Deposição de Material Particulado Emitido por Pilhas de Estocagem de Granulados: Uma Abordagem Numérica Empregando LES; Engenharia ambiental; Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo: Vitória, Brazil, 2014; p. 182.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).