Abstract

Accurate detection of concealed items in X-ray baggage images is critical for public safety in high-security environments such as airports and railway stations. However, small objects with low material contrast, such as plastic lighters, remain challenging to identify due to background clutter, overlapping contents, and weak edge features. In this paper, we propose a novel architecture called the Contrast-Enhanced Feature Pyramid Network (CE-FPN), designed to be integrated into the YOLO detection framework. CE-FPN introduces a contrast-guided multi-branch fusion module that enhances small-object representations by emphasizing texture boundaries and improving semantic consistency across feature levels. When incorporated into YOLO, the proposed CE-FPN significantly boosts detection accuracy on the HiXray dataset, achieving up to a +10.1% improvement in mAP@50 for the nonmetallic lighter class and an overall +1.6% gain, while maintaining low computational overhead. In addition, the model attains a mAP@50 of 84.0% under low-resolution settings and 87.1% under high-resolution settings, further demonstrating its robustness across different input qualities. These results demonstrate that CE-FPN effectively enhances YOLO’s capability in detecting small and concealed objects, making it a promising solution for real-world security inspection applications.

MSC:

68T01

1. Introduction

Ensuring public safety in high-risk environments such as airports, subways, and government facilities relies on the reliable automated detection of prohibited items in X-ray baggage screening systems. X-ray imaging offers strong penetration and material discrimination capabilities, enabling non-contact and non-destructive analysis of enclosed objects. As a result, it has been widely applied in both medical [1,2,3,4] and security [5] domains.

Despite extensive research on X-ray image analysis, most existing detection frameworks (e.g., Faster R-CNN, SSD, YOLOv5) are primarily optimized for natural image datasets such as COCO and Pascal VOC. When directly applied to X-ray imagery, their performance often degrades sharply due to the domain gap—manifested as low contrast, overlapping transparency, and lack of color cues. Moreover, conventional feature pyramids tend to overemphasize high-level semantics while neglecting boundary-sensitive cues critical for recognizing small and non-metallic items.

Unlike natural images, X-ray scans exhibit a complex overlap of multiple objects, where metallic and non-metallic materials interpenetrate under varying attenuation levels. This superposition leads to visual clutter and blurred boundaries, complicating small-object localization. In security screening scenarios, metallic threats (e.g., knives, firearms) typically exhibit strong X-ray absorption and distinct contours, making them relatively easy to detect. In contrast, non-metallic objects, such as plastic lighters, pose a significantly greater challenge due to their weak X-ray attenuation, low visual contrast, and frequent occlusion by surrounding clutter. Furthermore, the lack of color and texture diversity limits feature discriminability, posing a severe challenge even for advanced CNN- or transformer-based detectors. These characteristics often result in missed detections in real-world systems, thereby introducing serious security risks. Consequently, enhancing the visibility and detectability of small, concealed non-metallic items in X-ray images remains a critical challenge in security-oriented object detection.

To address these issues, we design a novel architecture that explicitly enhances contrast-sensitive and boundary-aware representations within the feature pyramid. The goal is to preserve fine-grained structural information across scales and improve robustness under heavy occlusion and low contrast conditions, which are prevalent in real-world X-ray security screening.

The contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- A novel feature pyramid network, termed the Contrast-Enhanced Feature Pyramid Network (CE-FPN), is proposed for integration into the YOLO framework. It incorporates a contrast-guided multi-branch fusion module to enhance the representation of small and low-contrast objects in cluttered X-ray security images.

- The proposed multi-branch design simultaneously improves boundary sensitivity and semantic consistency across feature scales, enabling more accurate detection of visually ambiguous items, such as plastic lighters, even under occlusion and overlapping conditions.

- Extensive experiments demonstrate that CE-FPN consistently outperforms mainstream FPN-based detectors, achieving notable accuracy improvements while maintaining a lightweight computational cost.

2. Related Work

In recent years, significant progress has been made in object detection for X-ray security inspection imagery. Existing approaches can be broadly categorized into traditional image-analysis-based methods and deep-learning-based methods. Representative studies of both categories are reviewed below.

2.1. Traditional Methods for X-Ray Baggage Object Detection

Early research primarily relied on handcrafted features and classical machine learning algorithms. For example, some studies extracted local features using Bag of Visual Words (BoVW) models and then applied Support Vector Machines (SVM) for prohibited-item classification [6]. These methods depend heavily on manually designed features such as edges and textures, making them sensitive to image quality and occlusions, and often struggle with achieving high recall in complex baggage imagery.

To evaluate such traditional approaches, Mery et al. constructed the public GDXray dataset [6], which contains more than 19,000 X-ray images across several categories including luggage, castings, and welds. Although traditional methods achieved notable results on GDXray, overall detection accuracy was limited.

To address the issue of overlapping objects causing missed detections, Mery and Katsaggelos introduced a logarithmic X-ray imaging model for baggage inspection [7]. Their model transforms the multiplicative nature of foreground–background overlap into an additive relation in the log domain, enabling linear separation strategies to segment suspicious objects from complex backgrounds. Using sparse representation within this framework, the method successfully detected concealed knives, blades, and guns in simulated X-ray baggage imagery.

2.2. Deep Learning-Based Methods for X-Ray Baggage Object Detection

With the rise of deep learning, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have demonstrated powerful capabilities in X-ray image analysis [8]. Akçay et al. systematically explored CNN architectures for object classification and detection within X-ray baggage images [8]. Even with most convolutional layers frozen, transfer-learned CNNs significantly outperformed traditional BoVW + SVM methods in binary classification tasks.

Large-scale datasets have also accelerated progress. Miao et al. introduced the SIXray dataset [9]. The dataset includes highly overlapped scenes, making detection extremely challenging. To address extreme class imbalance and occlusion, they proposed the Class-Balanced Hierarchical Refinement (CHR) model [9], which incorporates reverse connections and cascaded refinement to better distinguish targets in cluttered scenes.

Occlusion-focused datasets have further enriched the field. Wei et al. constructed the OPIXray dataset [10], which includes 8885 images of five types of knives under varying degrees of occlusion. They introduced the De-occlusion Attention Module (DOAM), which enhances existing detectors by generating attention maps from X-ray-specific color–texture cues. DOAM significantly improved detection performance under heavy occlusion.

Recognizing that real-world inspection involves deeply hidden objects, Tao et al. [11] presented the HiXray dataset and proposed a Lateral Inhibition Module (LIM) to suppress noisy background and highlight boundary cues via bidirectional propagation and boundary activation.

To further tackle severe occlusion and exploit global context, Ma et al. [12] proposed a Global Context-aware Multi-Scale Feature Aggregation (GCFA) framework, which integrates a learnable Gabor convolution layer, a Spatial-Attention (SA) mechanism, a Global Context Feature Extraction (GCFE) module, and a Dual-Scale Feature Aggregation (DSFA) module. Experiments on SIXray, OPIXray and WIXray show that this method achieves state-of-the-art performance under heavy occlusion.

Additionally, Transformer-based architectures have recently emerged as a new direction in X-ray image analysis. Vision Transformers (ViT) enable global context modeling through self-attention, addressing the locality limitations of CNNs. Studies have shown that Transformer-enhanced detectors such as Swin-Transformer Faster R-CNN and Deformable DETR outperform CNN-only detectors on SIXray and OPIXray [13]. Although pure Transformer models are computationally expensive, hybrid CNN–Transformer architectures offer a promising balance between accuracy and efficiency.

Ma et al. [14] proposed a Transformer-based two-stage “coarse-to-fine” framework for prohibited-object detection in X-ray images. They introduce Position & Class Object Queries (PCOQ) and a Progressive Transformer Decoder (PTD) that distinguishes high- and low-score queries (where low-score queries correspond to heavily occluded objects). Their method improves accuracy on datasets such as SIXray, OPIXray and HiXray, while reducing model computational complexity by 21.6% compared to baseline DETR.

Recent research has increasingly focused on overcoming the challenges of object occlusion, low contrast, and cluttered backgrounds in X-ray baggage images, as these factors significantly hinder the detection of small or concealed items.

Zhu et al. [15] proposed FDTNet, a frequency-aware dual-stream transformer network designed for detecting prohibited objects in X-ray images, which enhances detection accuracy by utilizing frequency domain features and attention mechanisms. Hassan et al. [16]. proposed a novel incremental convolutional transformer system that effectively detects overlapping and concealed contraband in baggage X-ray scans through a distillation-driven incremental instance segmentation scheme. Meng et al. [17] proposed a dual-view feature fusion and prohibited item detection model based on the Vision Transformer framework for X-ray security inspection images, utilizing dual-view security inspection equipment to address issues of object occlusion and poor imaging angles in single-view imaging.

YOLO-based object detectors have demonstrated remarkable robustness across heterogeneous imaging domains. For example, they have been successfully applied to real-time fracture detection in borehole image logs with high precision [18], as well as to fracture identification from conventional well-log data using sliding-window image constructions [19]. Although these studies originate from subsurface reservoir characterization rather than security inspection, they share similar challenges—including complex backgrounds, subtle target features, and strong class imbalance—which closely mirror the difficulties encountered in X-ray baggage imagery. The consistent performance of YOLO across such diverse modalities provides compelling evidence of its adaptability to non-standard visual data and further underscores its suitability for X-ray security inspection tasks.

Overall, deep learning approaches—especially CNNs, Transformers, and hybrid architectures—have become the dominant paradigm in X-ray baggage object detection, achieving state-of-the-art performance on multiple public benchmarks and moving the field closer to real-world, high-accuracy automated security inspection.

3. Methodology

We propose CE-FPN to improve the detection of small and visually ambiguous objects in cluttered X-ray security images. The proposed module is designed as a plug-and-play neck component and integrated into the YOLO11 detection framework by replacing its default FPN. CE-FPN enhances small object representation by jointly leveraging multi-scale semantic information, local contrast cues, and cross-level feature consistency.

3.1. Design Motivation

Detecting small objects such as nonmetallic lighter in X-ray baggage images is particularly challenging due to weak visual contrast, overlapping contents, and blurred boundaries. Conventional feature pyramid structures in one-stage detectors, including the original YOLO11 neck, primarily rely on top-down pathways to fuse semantic information, but often fail to retain fine-grained spatial details or emphasize regions with significant contrast.

To address these limitations, CE-FPN is designed with two key objectives: (1) to preserve and enhance edge and texture cues that are critical for detecting small, low-contrast objects; and (2) to reinforce cross-scale semantic consistency while amplifying contrast-relevant regions.

3.2. Architecture of Proposed Method

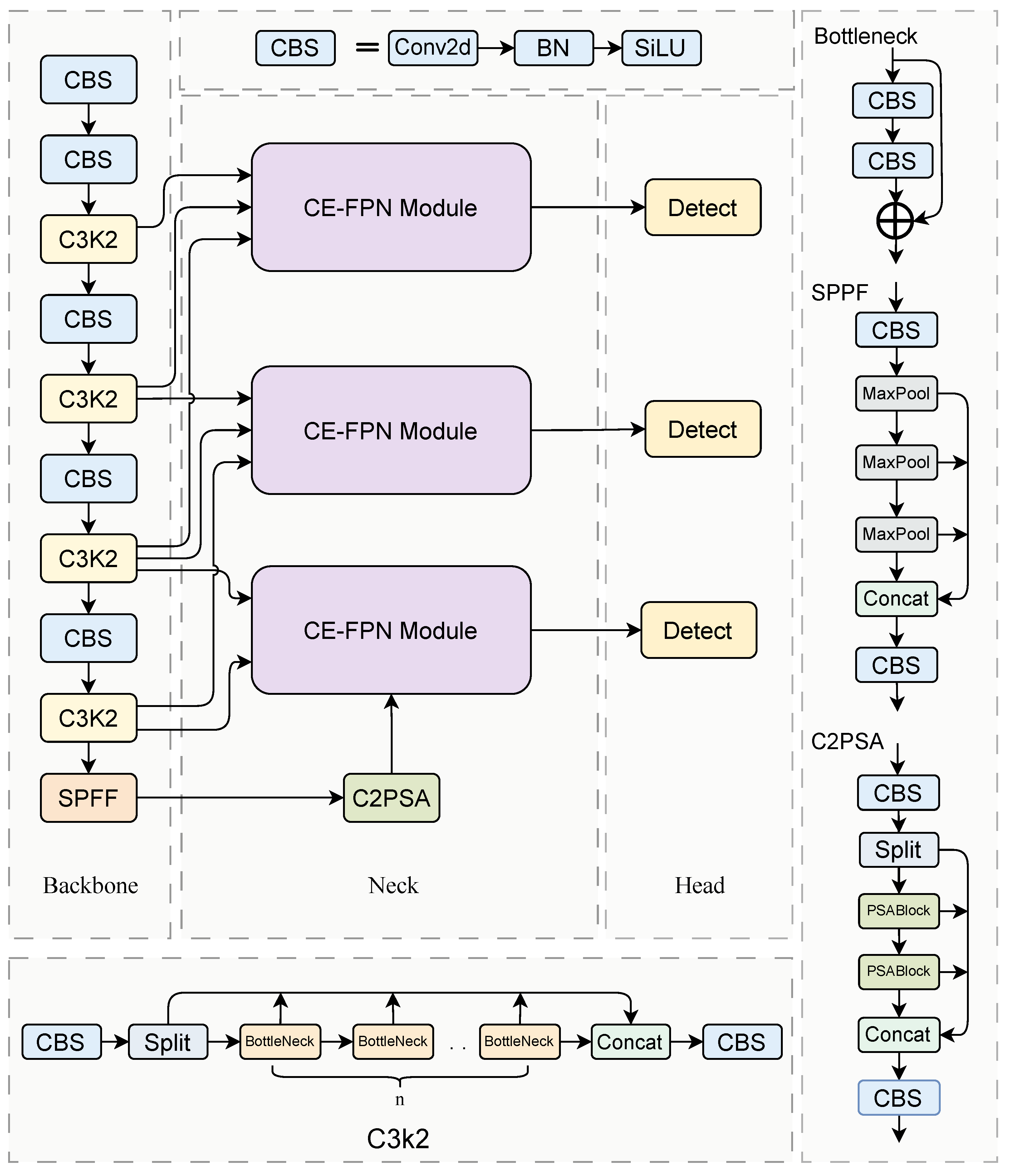

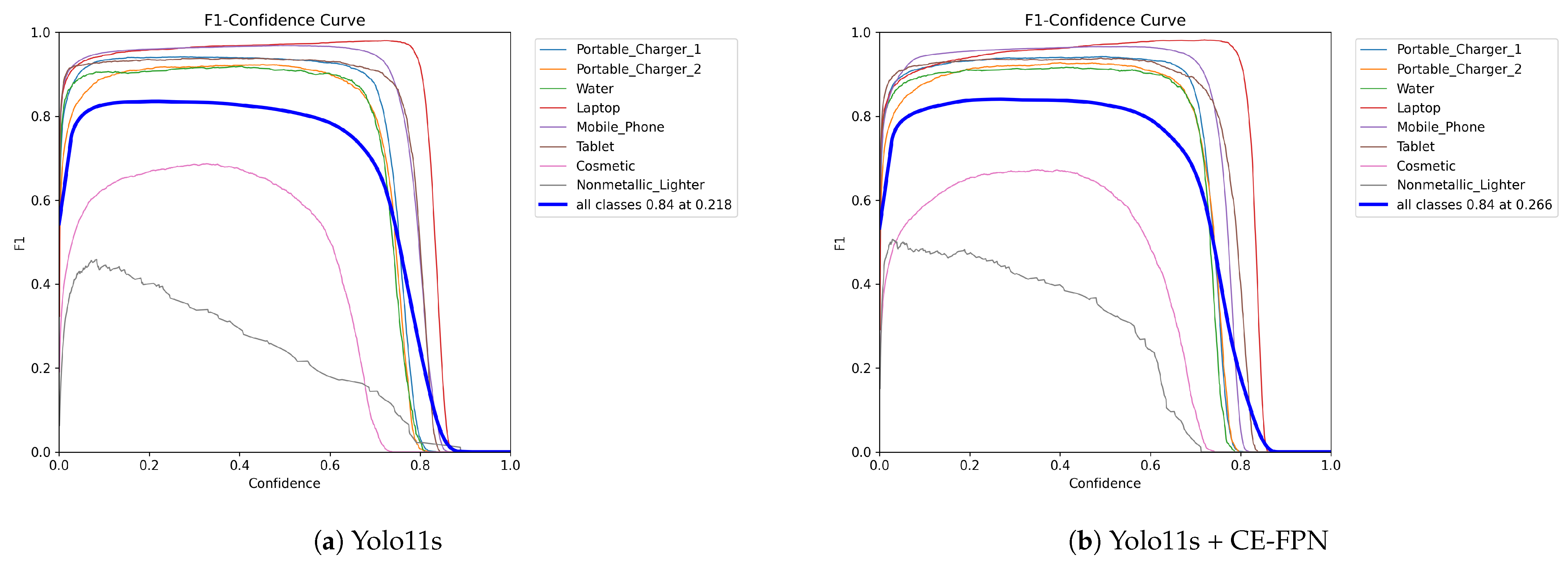

The proposed object detection framework is based on the YOLO11 architecture, in which the original neck component is replaced by the proposed CE-FPN module. The overall network consists of three primary stages: a backbone for hierarchical feature extraction, the CE-FPN neck for contrast-guided multi-scale feature refinement, and a detection head for object classification and localization. The overall architecture is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Architecture of the proposed CE-FPN-enhanced detection framework.

We adopt the CSPDarknet backbone from YOLO11, which generates hierarchical feature maps at three different spatial resolutions via successive convolutional and residual layers. These feature maps capture visual patterns at multiple levels of abstraction and serve as inputs to the neck module.

The extracted multi-scale features are fed into the proposed CE-FPN, which incorporates a contrast-guided multi-branch fusion mechanism. This module enhances object representations by: (1) preserving shallow spatial details such as edges and textures, (2) enriching semantic context across scales, and (3) emphasizing regions of high local contrast through spatial attention. The resulting features are both semantically coherent and contrast-sensitive, making them well-suited for detecting small and ambiguous objects in cluttered X-ray baggage images.

The refined features produced by CE-FPN are passed to the standard YOLO detection head, which performs anchor-based bounding box regression and object classification at three scales. The detection head remains unchanged, ensuring compatibility with existing training and inference pipelines.

This modular design enables CE-FPN to serve as a plug-and-play replacement for the standard neck in one-stage detectors. In Section 4, we further demonstrate the versatility of our approach by integrating CE-FPN into additional detection frameworks, including YOLOv5 and YOLOv8.

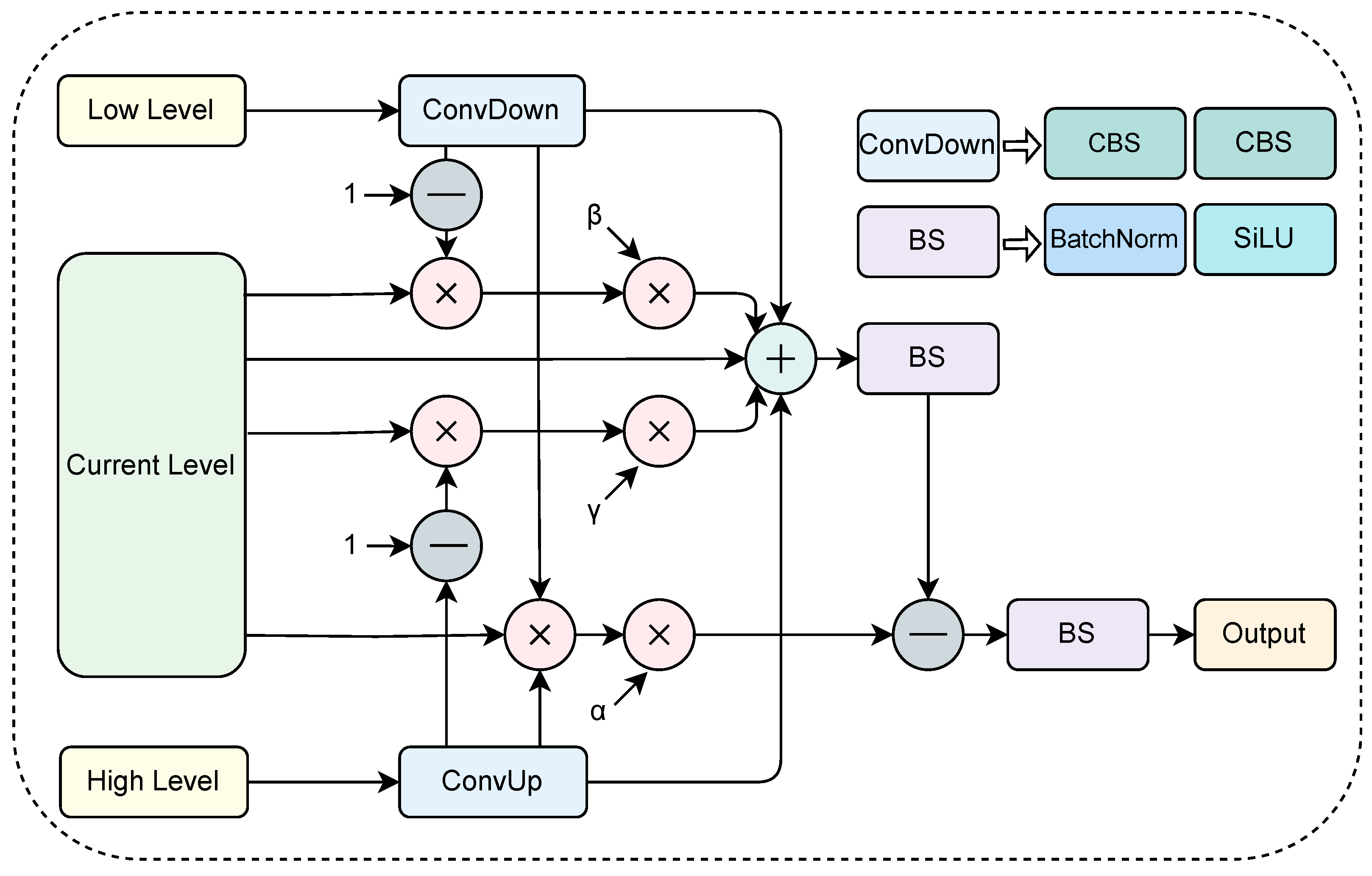

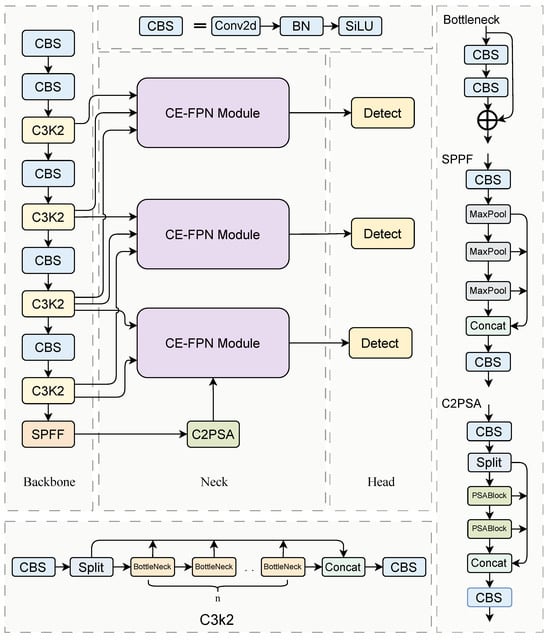

3.3. CE-FPN

As illustrated in Figure 2, the proposed CE-FPN is a contrast-aware, multi-branch fusion module designed to enhance the representation of small and visually ambiguous objects, such as nonmetallic lighters, in complex X-ray baggage images. It addresses the limitations of conventional FPNs by jointly leveraging spatial contrast and semantic hierarchy within a unified, learnable framework.

Figure 2.

Architecture of the proposed CE-FPN module. Low-, current-, and high-level features are integrated through learnable weights (α, β, γ) and refined via two BS blocks (BatchNorm + SiLU), enabling contrast- and semantic-aware feature fusion.

3.3.1. Feature Representation and Motivation

Let x, y, and z denote the high-level, mid-level, and low-level feature maps extracted from the backbone (e.g., YOLO11’s C5, C4, and C3 layers), with corresponding channel dimensions C1, C2, and C3. These features represent different levels of abstraction:

- x: semantically rich but lacking spatial detail,

- z: rich in spatial detail (edges and textures) but semantically shallow,

- y: intermediate-level features, serving as the fusion base.

The objective of CE-FPN is to fuse these three feature representations through a contrast-guided strategy, allowing the network to emphasize foreground object regions while suppressing background noise and irrelevant information.

To integrate multi-level representations, CE-FPN formulates the fusion process as:

where denotes the overall feature fusion operator.

To emphasize discriminative regions, a contrast-guided modulation is introduced:

where ψ(·, ·) and ϕ(·, ·) are contrastive enhancement functions designed to amplify feature disparities between foreground and background representations.

To achieve this, we design three consecutive stages: semantic enhancement, contrast reweighting, and learnable aggregation, as detailed below.

3.3.2. High-Level Semantic Enhancement

To align it with the mid-level feature , we apply a 3 × 3 convolution with padding 1 to transform the channel dimension to C2, followed by bilinear upsampling to match the spatial resolution. This process ensures that high-level semantic features, which typically have lower spatial resolution, are projected into a compatible feature space before fusion. The resulting activation is used as a semantic attention mask, formulated as:

This semantic mask captures the global contextual information from high-level representations, guiding subsequent fusion by highlighting regions that are semantically relevant to potential object areas. In essence, it acts as a spatial prior emphasizing object-centric regions and suppressing background noise.

3.3.3. Low-Level Contrast Reweighting

The low-level feature , which contains fine-grained edge and texture information, is first projected into a reduced channel dimension C2 and spatially downsampled to match the resolution of y:

This operation generates a contrast-oriented map that encodes local structural details, such as object boundaries and intensity gradients, which are often lost in deeper layers. By combining two consecutive convolutions with different strides, both local edge information and downsampled contextual cues are retained. The resulting masklow thus serves as a complementary attention cue to the high-level mask.

The reweighting process begins by enhancing the mid-level feature y with the semantic guidance from maskhigh:

This element-wise multiplication emphasizes semantically meaningful regions while suppressing irrelevant background responses. Subsequently, the low-level contrast map refines this result by injecting edge-sensitive cues:

Here, the fine-grained contrast attention selectively strengthens high-frequency spatial details around object boundaries, helping the model to better detect low-contrast or small objects that are easily overlooked.

Meanwhile, two complementary components are derived to suppress redundant semantics and contrast information:

Consequently, three refined feature components are obtained: the foreground-enhanced feature fp, the semantic-suppressed feature fn1, and the contrast-suppressed feature fn2. This triplet formulation enables the network to jointly model foreground and suppressed cues, thereby balancing enhancement and suppression across semantic and structural dimensions. The algorithmic procedure of CE-FPN is shown in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Forward propagation of the CE-FPN module |

|

3.3.4. Learnable Feature Aggregation

To adaptively integrate these three refined branches, learnable weights α, β, and γ are introduced to balance their relative contributions. The aggregated feature is formulated as:

This intermediate representation captures both semantic and contrastive cues from multiple feature levels. It is then refined via a normalization and activation process:

where BS(·) denotes a Batch Normalization layer followed by a SiLU activation, which stabilizes feature distribution and enhances nonlinearity.

This fusion strategy mitigates the semantic dilution problem commonly found in standard FPNs by leveraging contrast as a visual cue. It effectively enhances the objectness of low-visibility targets and improves feature discrimination, especially for small objects embedded in cluttered or low-contrast environments.

Unlike conventional FPNs that mainly rely on top–down semantic propagation, CE-FPN explicitly integrates spatial contrast and semantic hierarchy during feature fusion. The high-level semantic mask highlights object-centric regions, while the low-level contrast mask preserves boundary- and texture-related cues that are often suppressed in deeper layers. Through complementary branches and learnable aggregation weights, CE-FPN simultaneously strengthens discriminative foreground responses and suppresses background clutter—addressing the key limitation of standard FPNs in detecting small, low-contrast objects in X-ray imagery.

Moreover, while existing FPN variants such as BiFPN, PANet, NAS-FPN, and attention-enhanced pyramids primarily improve multi-scale fusion pathways, they generally do not explicitly model localized contrast cues or boundary-aware structures, which are essential for objects with weak attenuation or heavy overlap. CE-FPN’s contrast-guided multi-branch design provides a unified mechanism that jointly captures both semantic priors and fine-grained structural details, offering a principled advantage in challenging X-ray scenarios where conventional pyramids lose small-object information.

4. Experiments

4.1. Dataset and Experimental Configuration

In this paper, we conduct experiments on the HiXray dataset [11] that provides diverse and realistic X-ray baggage images of carry-on baggage. The HiXray dataset consists of 45,364 images with 102,928 annotated objects across eight categories and is particularly suitable for evaluating detection models under occlusion and visual clutter, and it notably contains small and visually ambiguous items, including non-metallic threats that are challenging to detect in X-ray baggage images and are typically scarce in previous datasets. Table 1 shows the data distribution of the Hixray dataset.

Table 1.

Data distribution of training and testing samples for Hixray dataset.

All experiments are conducted on a workstation running Ubuntu 20.04.5 LTS with an NVIDIA Tesla A100 GPU. The model is implemented using PyTorch 2.0.0. We adopt Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) as the optimizer, with a weight decay of 0.0005 and an initial learning rate of 0.01. The total number of training epochs is set to 200, with a batch size of 32. During preprocessing, all input images are resized to a fixed resolution of 640 pixels and 1280 pixels while maintaining aspect ratio. All remaining hyperparameters, data augmentations, and training routines not explicitly stated follow the default YOLO implementation settings.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively assess the detection performance of the proposed CE-FPN-based framework, we adopt three standard metrics widely used in object detection: Precision (P), Recall (R), and mean Average Precision at an IoU threshold of 0.5 (mAP@50). These indicators measure the model’s ability to correctly identify prohibited items while minimizing false alarms.

4.2.1. Precision and Recall

Precision evaluates the proportion of correctly predicted positive samples, reflecting the detector’s reliability in avoiding false alarms. Recall measures the proportion of actual positive samples that are successfully detected, indicating the model’s capability to avoid missed detections. Given the number of true positives (TP), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN), Precision and Recall are defined as:

Higher Precision indicates fewer incorrect detections, while higher Recall indicates fewer missed instances—both critical in X-ray security screening, particularly for concealed or low-contrast prohibited objects.

4.2.2. Mean Average Precision at IoU = 0.5 (mAP@50)

To quantify the overall detection accuracy across confidence thresholds, we use mean Average Precision (mAP). mAP@50 computes the area under the Precision–Recall curve at an IoU threshold of 0.5. For a given class c, the Average Precision (AP) is calculated as:

The mAP@50 over N object categories is then defined as:

This metric reflects the model’s capability to accurately localize and classify objects under moderate localization constraints and is widely adopted in X-ray prohibited-item detection benchmarks.

4.3. Analysis of Results

4.3.1. Ablation Experiment

Table 2 compares the baseline YOLO11 model with its CE-FPN-enhanced variant. The proposed CE-FPN yields a clear improvement in overall mAP@50, increasing from 85.5% to 87.1%. The most notable gain occurs in the challenging Nonmetallic_Lighter class (+10.1 mAP@50), which contains small and low-contrast objects that are easily obscured in X-ray imagery. This substantial improvement highlights CE-FPN’s effectiveness in strengthening discriminative cues for visually ambiguous targets. Moderate gains are also observed for Tablet and Cosmetic, while performance on large, easily detectable categories (e.g., Laptop, Portable_Charger) remains stable, confirming that CE-FPN does not degrade performance on simpler cases.

Table 2.

Ablation results of YOLO11 with CE-FPN.

Regarding Precision (P) and Recall (R), CE-FPN produces a slight decrease in Precision for several categories but consistently improves Recall across most classes. This reflects a shift toward greater sensitivity to subtle object cues—an advantageous behavior for safety-critical X-ray screening, where missed detections are far more costly than additional false positives. The Recall gain for Nonmetallic_Lighter (+5.3) is particularly significant, indicating that CE-FPN enhances the model’s ability to capture faint signals from small or weakly attenuating objects.

As shown in Table 3, removing either the high-level or low-level branch leads to performance drops compared to the full CE-FPN. Notably, excluding the low-level branch (w/o Low) results in a larger decline, highlighting its importance in capturing spatial details. When both branches are removed, performance drops below the baseline, confirming that their joint design is essential for robust detection in cluttered X-ray baggage images.

Table 3.

Ablation study of CE-FPN design components.

As shown in Table 4, CE-FPN achieves the highest mAP@50 of 87.1%, outperforming both attention-based modules (SENet, CBAM) and fusion structures (BiFPN, ASFF). These results indicate that CE-FPN provides more effective feature enhancement and fusion, enabling better detection performance than existing alternatives.

Table 4.

Comparison of CE-FPN with other advanced fusion or attention modules.

4.3.2. Generalization Across Architectures

As shown in Table 5, the proposed CE-FPN module consistently improves detection accuracy across all YOLO variants while introducing a reasonable increase in model complexity. For instance, on YOLOv5, CE-FPN raises the mAP@50 from 84.2% to 86.3%, with parameter count increasing from 7.0M to 13.5M and GFLOPs from 16.0 to 34.6. Similar trends are observed on YOLOv8 and YOLO11, with mAP@50 gains of 1.1% and 1.6%, respectively.

Table 5.

CE-FPN performance across YOLO models.

Notably, the relative performance improvement remains stable across architectures, suggesting that CE-FPN is agnostic to the backbone and compatible with a variety of detection heads. Despite the added computational cost, the improved accuracy—especially in detecting small and low-contrast objects—justifies the inclusion of CE-FPN in scenarios where detection reliability is critical, such as X-ray security screening.

4.3.3. Controlled Experiment

Table 6 compares our CE-FPN-enhanced detectors with a wide range of state-of-the-art object detection models on the HiXray dataset under both low- and high-resolution settings. The evaluated models span classical two-stage frameworks (e.g., Faster R-CNN [20], RetinaNet [21], RepPoints [22]) as well as modern one-stage detectors from the YOLO family (YOLOv5–YOLOv13) [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31], covering a diverse set of model sizes and design philosophies. This comprehensive benchmark enables a balanced evaluation of accuracy, computational complexity, and model scalability across different resolution regimes.

Table 6.

Comparison of CE-FPN-enhanced models with advanced methods (low and high resolution).

In terms of performance, CE-FPN consistently improves baseline detectors across different YOLO variants. At low resolution, integrating CE-FPN into YOLOv5s, YOLOv8s, and YOLO11s yields mAP@50 increases of 0.8%, 0.4%, and 1.3%, respectively. Across both settings, YOLO11s + CE-FPN consistently achieves the highest mAP@50, reaching 84.0% in low resolution and 87.1% in high resolution. These results clearly outperform several larger or more complex architectures, while maintaining a significantly smaller computation.

Moreover, the results highlight CE-FPN’s versatility: it functions as a lightweight, modular enhancement that generalizes well across different YOLO generations. This allows it to improve detection without requiring changes to the backbone architecture or additional supervision, making it suitable for practical deployment in resource-constrained environments such as real-time X-ray security screening systems.

In addition to performance, CE-FPN maintains a favorable computational profile. For instance, YOLOv5s + CE-FPN requires only 13.5 M parameters and 34.4 GFLOPs, significantly lower than two-stage detectors like Faster R-CNN (41.2 M, 215.7 GFLOPs) or MAM Faster R-CNN (47.7 M, 247.3 GFLOPs), while still achieving a higher mAP@50. Even the largest of our variants, YOLO11s + CE-FPN, stays well under 16.4 M parameters and 60.5 GFLOPs, which is efficient for deployment on edge GPUs or real-time systems.

To further evaluate the robustness and cross-domain generalization ability of the proposed CE-FPN, we additionally conduct experiments on the publicly available OPIXray dataset. As shown in the Table 7, our CE-FPN-enhanced YOLO11s consistently outperforms other advanced X-ray object detection methods and DETR-based methods, which demonstrates that the proposed contrast-guided feature pyramid is not limited to the HiXray dataset but also transfers effectively to another benchmark containing different imaging conditions, occlusion patterns, and threat object types. These results further confirm the applicability of CE-FPN to broader X-ray security inspection scenarios.

Table 7.

Comparison of advanced X-ray object detection methods and DETR-based methods on OPIXray.

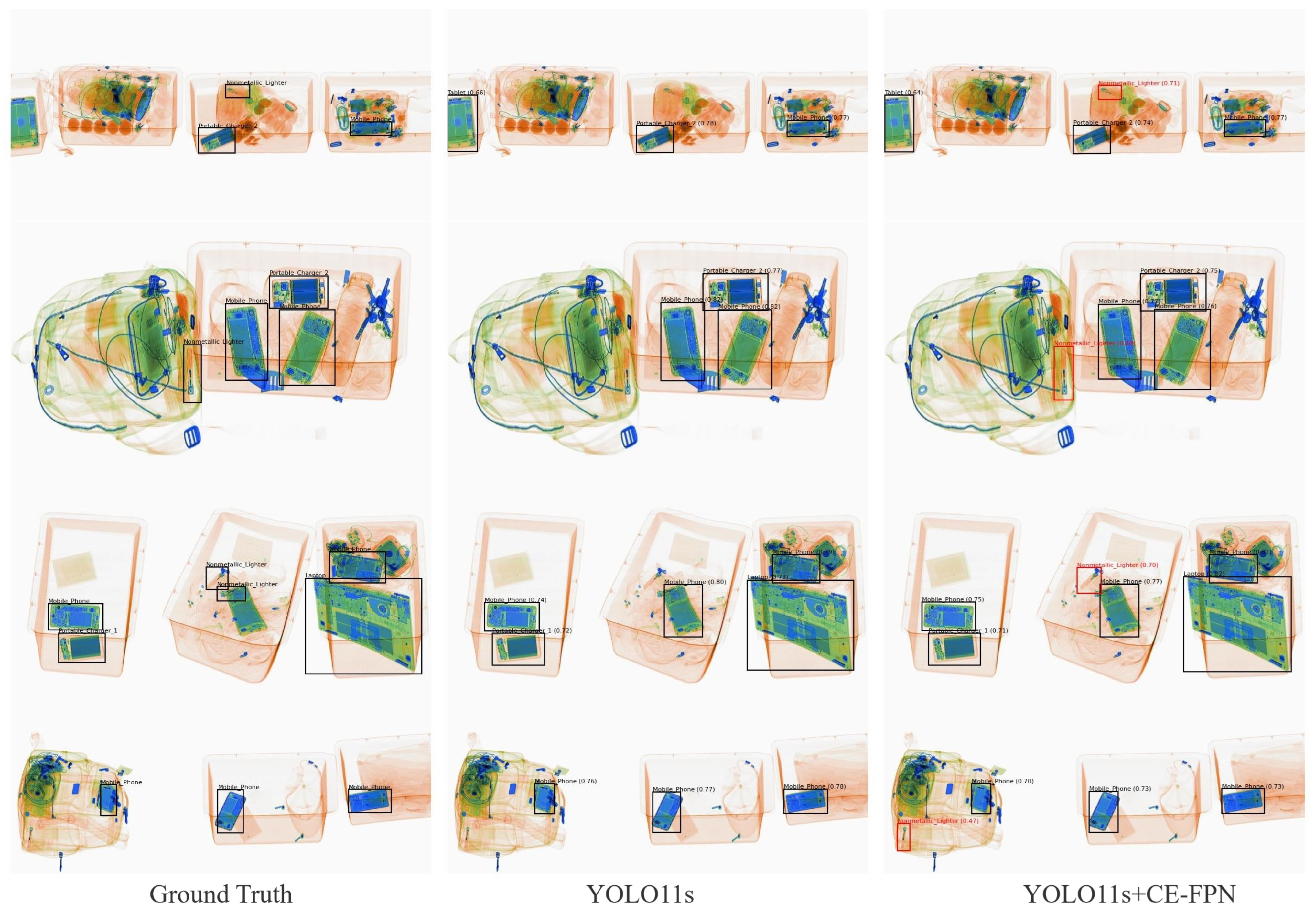

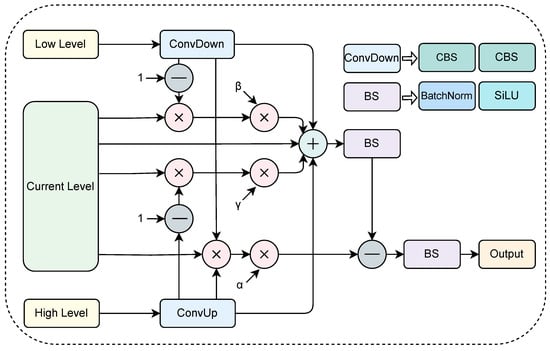

4.3.4. Qualitative Analysis

Figure 3 presents qualitative comparisons between the baseline YOLO11s model and our enhanced YOLO11s + CE-FPN on several challenging X-ray samples. Compared with the baseline, the CE-FPN-enhanced model demonstrates improved capability in detecting visually ambiguous or low-contrast items, such as Nonmetallic Lighter, which are often missed by the original network.

Figure 3.

Qualitative comparison.

Notably, in multiple examples, the baseline YOLO11s fails to detect Nonmetallic_Lighter instances altogether, likely due to their low contrast, small size, or heavy occlusion. In contrast, the CE-FPN-enhanced model successfully localizes these challenging objects with accurate bounding boxes and reasonable confidence scores.

We also observed occasional false positives in extremely cluttered regions. As illustrated in the last row of Figure 3, CE-FPN incorrectly identifies a lighter-like pattern where the baseline produces no detection. This suggests that while contrast enhancement improves recall, it may also amplify weak structural patterns that resemble small threats under heavy clutter.

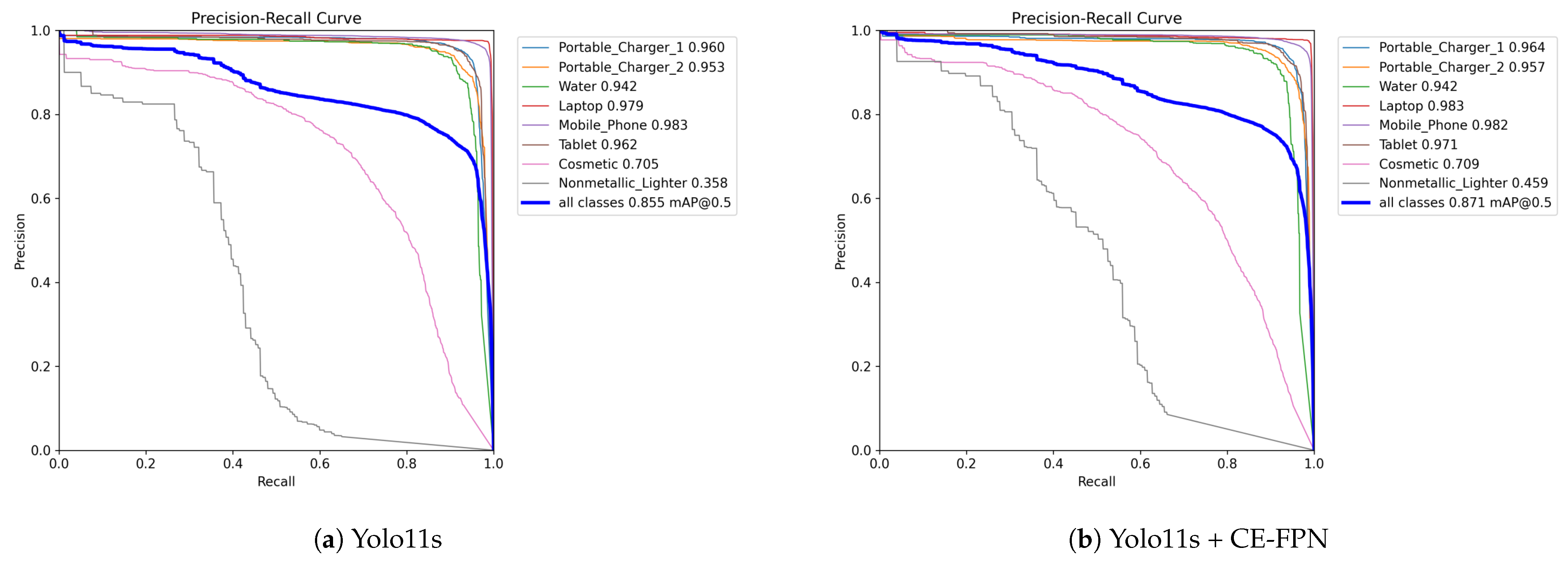

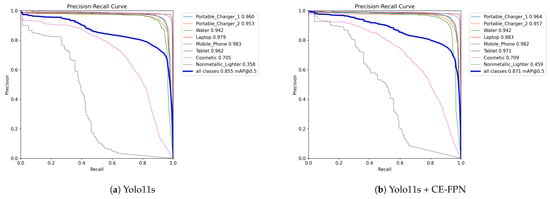

4.3.5. Precision–Recall Trade-Off in Safety-Critical Scenarios

As shown in the precision–recall curves in Figure 4, CE-FPN exhibits a generally improved precision–recall profile compared with the baseline. Although the two curves partially overlap, the overall trend indicates a larger area under the PR curve, which is consistent with the mAP@50 improvement from 85.5 to 87.1 (+1.6%). It is worth noting that the PR curve inherently evaluates performance across all confidence thresholds, thus providing a fair and comprehensive assessment of detection behavior. This also mitigates the potential bias introduced by fixing the confidence and NMS parameters to the same default values for all methods. The consistent mAP@50 gain further confirms that, even under unified settings, CE-FPN maintains a better overall balance between precision and recall that enhancing sensitivity to low-contrast objects without causing excessive false positives. To quantitatively assess this trade-off, we compared recall at fixed precision levels for both the baseline YOLO11s and our proposed CE-FPN. As summarized in Table 8, CE-FPN consistently achieves higher recall across all high-precision operating points. Specifically, at P = 90%, recall improves from 41.7% to 51.4% (+9.7%), and at P = 85%, from 51.9% to 61.7% (+9.8%), showing that CE-FPN substantially enhances sensitivity to low-contrast targets while maintaining stringent false-alarm tolerance.

Figure 4.

Comparison of PR curves between Yolo11s and Yolo11s+CE-FPN. The CE-FPN module enhances feature fusion and leads to noticeable improvements in detection performance.

Table 8.

Precision–Recall trade-off analysis.

Even under very conservative settings (P = 95%), recall still rises from 26.5% to 30.5%, indicating that the contrast-guided fusion allows more reliable detection of small, low-contrast threats (e.g., Nonmetallic_Lighter) without disproportionately increasing false positives. At moderate precision levels (P = 75–80%), the recall gap remains positive (+1.5 to 3.2%), confirming consistent improvement across different operating regimes.

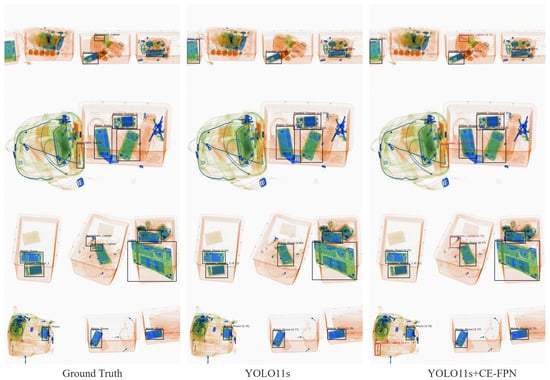

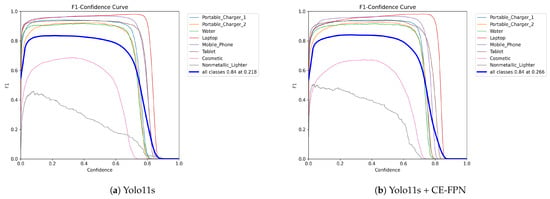

Figure 5 compares the F1–confidence curves of the baseline YOLO11s and our CE-FPN-enhanced model. The CE-FPN variant consistently achieves higher F1 scores across a wide confidence range, improving the optimal all-class F1 from 0.84 @ 0.218 (baseline) to 0.84 @ 0.266. This shift indicates that the enhanced model maintains stronger precision–recall balance at higher confidence thresholds. Notably, the Nonmetallic_Lighter class—characterized by extremely low contrast and small object size—shows a visibly more stable F1 curve, reflecting improved robustness in detecting weak-visibility objects. These results further validate that CE-FPN strengthens small-object discrimination while suppressing confidence-sensitive fluctuations.

Figure 5.

Comparison of F1 curves between Yolo11s and Yolo11s + CE-FPN.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposed CE-FPN, a contrast-enhanced feature pyramid network designed to improve the detection of small, low-contrast objects in X-ray baggage images. Experiments on the HiXray dataset show that CE-FPN achieves up to a +10.1% increase in mAP@50 for the nonmetallic lighter class and a +1.6% overall improvement, while maintaining low computational cost. These results underscore the practical value of CE-FPN for real-time X-ray object detection in high-risk security scenarios, highlighting both its technical contribution and real-world applicability. Future work will explore extending this approach to multi-view or multi-modal X-ray baggage images.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.C., T.L. and Z.C.; methodology, Q.C.; investigation, Q.C.; data curation, Q.C. and Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.C.; writing—review and editing, T.L. and Z.C.; formal analysis, J.L. and Y.L.; visualization, J.L.; supervision, T.L. and Z.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Science and Technology Development Fund of Macau under Grants 0194/2024/AGJ and 0037/2023/ITP1, and in part by the Macau University of Science and Technology Faculty Research Grants under Grant FRG-24-025-FIE.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets and code for this paper can be obtained from the following websites (accessed on 14 November 2025): https://github.com/HiXray-author/HiXray, https://github.com/OPIXray-author/OPIXray, https://github.com/jameschengds/CE-FPN.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rahman, F.; Wu, D. A Statistical Method to Schedule the First Exam Using Chest X-Ray in Lung Cancer Screening. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.H.; Le, H.; Dang, M.H.H.; Nguyen, V.D.; Do, P. Cross-Domain Approach for Automated Thyroid Classification Using Diff-Quick Images. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.; Choi, K. YOLO11-Driven Deep Learning Approach for Enhanced Detection and Visualization of Wrist Fractures in X-Ray Images. Mathematics 2025, 13, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarov, V.G.; Prokhorov, I.V.; Yarovenko, I.P. Identification of an Unknown Substance by the Methods of Multi-Energy Pulse X-ray Tomography. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriyanov, N. Using ArcFace Loss Function and Softmax with Temperature Activation Function for Improvement in X-ray Baggage Image Classification Quality. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mery, D.; Riffo, V.; Zscherpel, U.; Mondragon, G.; Lillo, I.; Zuccar, I.; Lóbel, H.; Carrasco, M. GDXray: The database of X-ray images for nondestructive testing. J. Nondestruct. Eval. 2015, 34, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mery, D.; Katsaggelos, A.K. A Logarithmic X-Ray Imaging Model for Baggage Inspection: Simulation and Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 283–290. [Google Scholar]

- Akcay, S.; Kundegorski, M.E.; Willcocks, C.G.; Breckon, T.P. Using Deep Convolutional Neural Network Architectures for Object Classification and Detection Within X-Ray Baggage Security Imagery. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2018, 13, 2203–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Xie, L.; Wan, F.; Su, C.; Liu, H.; Jiao, J.; Ye, Q. SIXray: A Large-Scale Security Inspection X-Ray Benchmark for Prohibited Item Discovery in Overlapping Images. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 2119–2128. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Tao, R.; Wu, Z.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X. Occluded Prohibited Items Detection: An X-ray Security Inspection Benchmark and De-occlusion Attention Module. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Seattle, WA, USA, 12–16 October 2020; pp. 1388–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, R.; Wei, Y.; Jiang, X.; Li, H.; Qin, H.; Wang, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X. Towards real-world X-ray security inspection: A high-quality benchmark and lateral inhibition module for prohibited items detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 10923–10932. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Zhuo, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. Occluded prohibited object detection in X-ray images with global Context-aware Multi-Scale feature Aggregation. Neurocomputing 2023, 519, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac-Medina, B.K.S.; Yucer, S.; Bhowmik, N.; Breckon, T.P. Seeing Through the Data: A Statistical Evaluation of Prohibited Item Detection Benchmark Datasets for X-Ray Security Screening. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 530–539. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Du, L.; Gao, Z.; Zhuo, L.; Wang, M. A Coarse to Fine Detection Method for Prohibited Object in X-ray Images Based on Progressive Transformer Decoder. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM ’24, New York, NY, USA, 16–19 June 2024; pp. 2700–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, N.; Ye, J.; Ling, X. FDTNet: Enhancing frequency-aware representation for prohibited object detection from X-ray images via dual-stream transformers. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, T.; Hassan, B.; Owais, M.; Velayudhan, D.; Dias, J.; Ghazal, M.; Werghi, N. Incremental convolutional transformer for baggage threat detection. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 153, 110493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Feng, H.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zou, W.; Ouyang, X. Transformer-based dual-view X-ray security inspection image analysis. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 138, 109382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizzadeh Mehmandost Olya, B.; Mohebian, R.; Bagheri, H.; Mahdavi Hezaveh, A.; Khan Mohammadi, A. Toward real-time fracture detection on image logs using deep convolutional neural network YOLOv5. Interpretation 2024, 12, SB9–SB18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Hao, J.; Zeng, L.; Yang, X.; Wang, L.; Ji, C.; Zhong, Z.; Chen, S.; Fu, K. A Deep Learning Object Detection Method for Fracture Identification Using Conventional Well Logs. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, S.; Hu, H.; Wang, L.; Lin, S. RepPoints: Point Set Representation for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 9657–9666. [Google Scholar]

- Jocher, G.; Qiu, J. Ultralytics YOLO11. Available online:https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/yolo11/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Jocher, G. Ultralytics YOLOv5. Available online:https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Weng, K.; Geng, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Z.; Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Nie, W.; et al. YOLOv6: A single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.02976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.M. YOLOv7: Trainable Bag-of-Freebies Sets New State-of-the-Art for Real-Time Object Detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar]

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; Qiu, J. Ultralytics YOLOv8. Available online:https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/yolov8/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Wang, C.Y.; Yeh, I.H.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv9: Learning What You Want to Learn Using Programmable Gradient Information. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. YOLOv10: Real-Time End-to-End Object Detection. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2024; Volume 37, pp. 107984–108011. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Ye, Q.; Doermann, D. Yolov12: Attention-centric real-time object detectors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12524. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, M.; Li, S.; Wu, Y.; Hu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, X.; Ding, G.; Du, S.; Wu, Z.; Gao, Y. YOLOv13: Real-Time Object Detection with Hypergraph-Enhanced Adaptive Visual Perception. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.17733. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H.; Huang, B.; Gao, H. Feature-Aware Prohibited Items Detection for X-Ray Images. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 8–11 October 2023; pp. 1040–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Sun, D.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Han, X.; Yang, H. ABTD-Net: Autonomous Baggage Threat Detection Networks for X-ray Images. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), Brisbane, Australia, 10–14 July 2023; pp. 1229–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, F.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X. An improved YOLOv8 model for prohibited item detection with deformable convolution and dynamic head. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2025, 22, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Yuan, P.; Wu, H.; Iwahori, Y.; Liu, Y. Improved YOLOv8 for Dangerous Goods Detection in X-ray Security Images. Electronics 2024, 13, 3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhu, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, H. MAM Faster R-CNN: Improved Faster R-CNN based on Malformed Attention Module for object detection on X-ray security inspection. Digit. Signal Process. 2023, 139, 104072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, Y. ScanGuard-YOLO: Enhancing X-ray Prohibited Item Detection with Significant Performance Gains. Sensors 2024, 24, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Du, H.; Mei, W.; Wang, S.; Yuan, D. Material-aware Cross-channel Interaction Attention (MCIA) for occluded prohibited item detection. Vis. Comput. 2023, 39, 2865–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ding, H.; Chen, C. AC-YOLOv4: An object detection model incorporating attention mechanism and atrous convolution for contraband detection in x-ray images. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 26485–26504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ma, B.; Wang, H.; Chen, D.; Jia, T. GADet: A Geometry-Aware X-Ray Prohibited Items Detector. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 1665–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Jia, T.; Wang, H.; Ma, B.; Lu, H.; Lin, S.; Cai, D.; Chen, D. AO-DETR: Anti-Overlapping DETR for X-Ray Prohibited Items Detection. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 12076–12090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Su, W.; Lu, L.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Dai, J. Deformable DETR: Deformable Transformers for End-to-End Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:cs.CV/2010.04159. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Jia, T.; Lu, H.; Ma, B.; Wang, H.; Chen, D. MMCL: Boosting deformable DETR-based detectors with multi-class min-margin contrastive learning for superior prohibited item detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.03176. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, A.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhong, L.; Zhang, L. Detecting prohibited objects with physical size constraint from cluttered X-ray baggage images. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 237, 107916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhu, L.; Dou, S.; Deng, W.; Wang, L. Detecting Overlapped Objects in X-Ray Security Imagery by a Label-Aware Mechanism. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2022, 17, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).