Abstract

Several Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA)-based benchmarking approaches have been proposed to enable step-by-step performance improvement; however, they frequently overlook the practical aspects necessary to ensure the feasibility and success of the benchmarking process for real-world operations. Simply, these approaches allow inefficient Decision Making Units (DMUs) to reach their targets step by step, thus facilitating gradual performance improvement. Most of the relevant studies in the literature have focused on stratifying DMUs into multiple efficiency layers. This paper introduces a new, practical DEA-based benchmarking framework tailored to the maritime port industry. Specifically, it proposes a feasibility-weighted multi-layer benchmarking path optimization (FW-MLBP) model that determines optimal stepwise benchmarking targets for inefficient ports by minimizing the total amount of controllable resource adjustment required at each stage. This model enables an inefficient port to select a series of manageable intermediate benchmarking targets from a set of efficient ports before ultimately reaching the best-performing one. To validate the effectiveness and practicality of our proposed methodology, we applied it to 30 international port terminals, successfully identifying their optimal stepwise benchmarking targets and demonstrating a viable, incremental path toward enhanced efficiency.

Keywords:

Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA); benchmarking path optimization; port-operational efficiency; port benchmarking MSC:

90C05

1. Introduction

The global economy of the 21st century has been fundamentally reshaped by maritime logistics. Approximately 90% of world trade is conducted via sea transport, involving over 1.2 billion tons of cargo and more than a billion containers annually, and ports have evolved into critical hubs of the global supply chain. The Asia-Pacific region is the world’s largest market for trade, with major ports such as Shanghai, Singapore, and Busan serving as vital nodes of international commerce. Significant vulnerabilities in port infrastructure, however, have been exposed by recent global disruptions including climate change, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Russia-Ukraine conflict. These events, leading to severe supply chain bottlenecks, have highlighted the urgency of efficiency maximization and adaptability enhancement for ports. As a consequence, efficiency evaluation and benchmarking have become essential strategies for sustained competitiveness and indeed, survival.

Ports, multifaceted platforms generating both economic and social value, face three pressing challenges. First, intensifying environmental regulations, among which is the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) target of a 40% carbon-emissions reduction by 2030, are obliging ports’ adoption of eco-friendly operations. Second, global shipping giants’ rapid implementation of smart port initiatives, entailing technologies such as blockchain, IoT, and AI, necessitates digital transformation. Third, there is a critical need for port-throughput optimization, which was underscored by the severe vessel backlogs and congestion incurred during the pandemic. In this context, efficiency evaluation allows for resource optimization, while benchmarking facilitates innovative-solution adoption, specifically by identifying, and learning from, best practices. These measures are no longer optional but imperative, particularly for ports’ successful navigation of an increasingly volatile world.

Benchmarking has been defined as “a continuous, systematic process for evaluating the products, services, and work processes of organizations that are recognized as representing best practices for the purpose of organizational improvement”. Among various approaches, Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) has been widely employed for benchmarking purposes [1]. DEA evaluates the relative efficiency of homogeneous Decision-Making Units (DMUs) by employing multiple performance metrics categorized as either inputs or outputs. In this way, it identifies a set of best-practice DMUs that form a trade-off curve, known also as the efficient frontier, comprising Pareto-optimal DMUs along with their respective performance scores [2,3]. These efficient DMUs serve as empirical benchmarking targets, while inefficient DMUs are assessed based on the extent to which their input or output levels deviate from those of the Pareto-optimal DMUs. For broader overviews of DEA methodologies and applications, see Liu et al. [4] for an early comprehensive survey and Emrouznejad and Yang [5], as well as more recent domain-specific reviews such as Fotova Čiković et al. [6]. From a practical benchmarking perspective, conventional DEA projections are often interpreted as requiring inefficient DMUs to close the entire efficiency gap to the efficient frontier in a single step, which can be difficult to implement when financial, resource, and operational constraints are substantial [4,7,8]. This issue becomes more pronounced where the efficiency gap is wider, as financial constraints, limited resources, and operational complexities, all of which make sudden, dramatic improvements virtually impossible, are unaccounted for. For port authorities, a single-step leap can be overwhelming and, indeed, demotivating. A step-by-step benchmarking approach becomes crucial, therefore, as it provides a more realistic and attainable pathway for gradual improvement; importantly, this allows ports to, over time, strategically allocate resources and implement changes, without disrupting ongoing operations.

Several alternative DEA-based benchmarking approaches have been proposed for step-by-step performance improvement [3,4,7,9,10,11,12,13]; however, they often neglect practical aspects necessary to ensure a feasible and successful benchmarking process for real-world port operations. These approaches, simply, allow inefficient DMUs to reach their targets step by step, thus facilitating gradual performance improvement. Most of the relevant studies in the literature have focused on stratifying DMUs into multiple efficiency layers.

The present research aimed to address this critical gap by developing a new and more practical DEA-based benchmarking framework that is tailored specifically to the maritime port industry. Unlike prior studies, crucially, our approach does not assume that a single leap to the efficient frontier is possible. Instead, it introduces a method for identification and selection of intermediate benchmarking targets in a stepwise manner, thereby providing a realistic and achievable performance improvement pathway. Specifically, we propose a feasible-weighted multi-layer benchmarking path optimization (FW-MLBP) model that determines optimal stepwise benchmarking targets for inefficient ports by minimizing the total amount of controllable resource adjustment required at each stage. In this way, the model enables an inefficient port to select a series of manageable intermediate benchmarking targets from a set of efficient ports before ultimately reaching the best-performing one. To validate the effectiveness and practicality of our proposed methodology, we applied it to 30 international port terminals, successfully identifying their optimal stepwise benchmarking targets and demonstrating a viable, incremental path toward enhanced efficiency.

2. Literature Review

There is a large body of literature on employment of DEA for port-efficiency evaluation. In this study, we limited our review to port benchmarking research that is directly relevant to our work and that highlights key differences from our approach.

Before discussing DEA-based benchmarking in detail, it is worth noting that traditional benchmarking practices in ports have relied heavily on ratio analysis, for example, throughput per berth, crane productivity, or various financial ratios. Ratio analysis is attractive because of its simplicity and transparency, but single or partial ratios cannot adequately represent multi-input–multi-output production processes and do not provide a unified efficiency frontier or systematic peer targets [14,15]. In contrast, DEA can be viewed as a generalization of ratio analysis that simultaneously considers multiple inputs and outputs, constructs an empirical efficiency frontier, and yields explicit benchmark units and improvement paths. In this study, we adopt DEA as the primary benchmarking tool and extend it further with a feasibility-weighted multi-layer path optimization framework tailored to port terminals.

Hayuth and Roll [16] were probably the first to attempt to apply DEA to port-efficiency evaluation. They used a CCR (Charnes, Cooper and Rhodes) DEA model to rate the efficiency of 20 container ports, utilizing three inputs and four outputs. Since then, various DEA studies on port terminal performance evaluation and benchmarking have been undertaken. Martinez-Budria et al. [17] developed a BCC model to evaluate the relative efficiencies of 26 Spanish ports based on 1993–1997 input and output data. Park and De [18] tested an alternative multi-stage DEA method for seaport-efficiency evaluation. Barros and Athanassiou [19] applied DEA to estimate the relative efficiencies of Portuguese and Greek seaports. Mithun and Song [20] proposed, for effective measurement of inefficient terminals, a diagnostic tool in the form of a stepwise projection method. This method uses data mining and DEA to reach the efficient frontier according to a port’s maximum capacity and similar input properties. Khalid [21] modeled container terminal operations as a container-flow process, analyzing both their site-specific and combined efficiency by applying a two-stage supply chain DEA model. Mithun and Song [13] proposed a new, decision-tree-based DEA model for benchmark optimization and DMU-variable prioritization in the container port industry. Their model had been designed to enhance both the flexibility and capability of classical DEA. Jaehun Park et al. [22] employed DEA to evaluate the efficiency of port units, proposing a stepwise path for inefficient ports’ setting of benchmarking targets and gradual efficiency improvement. Wang et al. [23] combined two-stage DEA with the Malmquist index in order to separately evaluate Vietnamese ports’ operational and logistics service efficiency. By validating rank stability through a resampling technique, they were able to identify stepwise improvement points and enhance the reliability of benchmarking results. Yu et al. [24] used context-dependent DEA for arrangement of Chinese coastal ports into performance-based layers, based on which they proposed a stepwise benchmarking path. Danladi et al. [25] used DEA to diagnose the efficiency level of individual ports, specifically by decomposing technical efficiency, pure technical efficiency, and scale efficiency. Li et al. [26] proposed a network DEA cross-efficiency model that considers, simultaneously, the initial network structure of port operations and greenhouse gas emissions. This model offers a new benchmarking approach that pursues both efficiency and sustainability by reflecting environmental constraints in increasing the differentiation among efficient units. Tsakalidis [27] utilized CCR/BCC models and window analysis to conduct a time-series comparison of major Mediterranean ports’ efficiencies. Ibeh et al. [28] applied a super-efficiency SBM model to evaluate major West African ports’ relative efficiencies. The analysis revealed more practical benchmarking targets for inefficient ports, namely unloading-productivity improvement and vessel turnaround time reduction, as the primary improvement tasks. Zhang et al. [29] used meta-frontier DEA to analyze and compare the efficiency of different clusters for 80 ports worldwide. Singh et al. [30] applied three-stage DEA to analyze port efficiency from a multidimensional perspective in carbon neutrality context. Their study accounted for both environmental and operational factors in deriving final rankings, and proposed a benchmarking roadmap for prioritization of green infrastructure investments.

Previous studies have proposed extended DEA models for port-efficiency evaluation; however, neither the characteristics nor the optimal utilization of resources were considered in benchmarking target selection. Particularly, they did not distinguish between resources that can be improved and those that cannot in rendering an inefficient DMU efficient. This limitation is critical in the port industry, where initial investments are, necessarily, very substantial. There are various capital-intensive resources that influence port efficiency; while some are useful for measuring efficiency scores, others cannot be easily reduced or expanded for efficiency improvement [22]. For instance, whereas port attributes such as berth length and yard area are meaningful indicators of efficiency, they are inappropriate for benchmarking, due particularly to the high costs of expansion or reduction in the real world. For this reason, categorizing resources into controllable and uncontrollable types, and incorporating this distinction into the selection of benchmarking targets, becomes practically very important.

In particular, existing stepwise benchmarking and network-based approaches such as Estrada et al. [7], Suzuki and Nijkamp [12], and Park and Sung [8] share several components with our framework in that they employ DEA stratification, multi-layer benchmark structures, and distance-based or proximity-based target selection. However, these studies generally do not embed explicit feasibility coefficients for controllable versus uncontrollable resources, nor do they formulate a global optimization model that minimizes a feasibility-weighted adjustment cost over the entire multi-layer benchmarking network. Moreover, their applications are not specifically tailored to port resources, where capital-intensive infrastructure such as berth length and yard area plays a critical role. In contrast, the present study integrates resource controllability into both the distance metric and the path selection process, and employs an MILP-based global optimization model to identify the most practical stepwise benchmarking path for port terminals.

In the present study, we applied a mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) model-based global optimization approach to determine stepwise benchmarking targets in consideration of the characteristics of port resources, in two key steps: first, benchmarking targets are selected such that improvements in uncontrollable resources are minimized; second, benchmarking targets are chosen such that the total adjustment of controllable resources is minimized. To achieve this, we propose a feasible-weighted multi-layer benchmarking path optimization (FW-MLBP) model, which allows for assignment of feasible weights to both controllable and uncontrollable resources. To the best of our knowledge, no previous research has considered this type of approach. In this respect, the main contribution of our study lies in its introduction of a new method of stepwise benchmarking that reflects a more realistic perspective on resource utilization in ports and, thereby, offers a practical pathway for inefficient ports’ efficiency improvement.

To clearly position the proposed FW-MLBP framework relative to existing stepwise benchmarking and network-based DEA approaches, we summarize the main similarities and differences in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative summary of stepwise benchmarking and network-based DEA approach.

3. Framework of Proposed Method

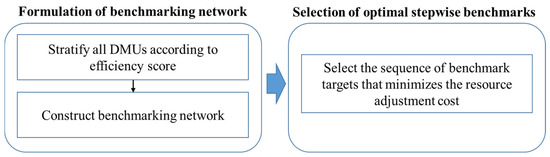

The framework of the proposed method consists of two parts, as illustrated in Figure 1: formulation of a benchmarking network, and selection of the optimal stepwise benchmarking targets. Here, the benchmarking targets are represented by the benchmarking ports. The procedure begins by stratifying all DMUs (ports) into several layers based on their efficiency scores. Once the DMUs are stratified, a benchmarking network is constructed, consisting of all possible sequences of intermediate benchmark targets (IBTs), which can be used as an inefficient DMU aiming to improve its efficiency score toward a final benchmarking target (FBT). Finally, the optimal stepwise benchmarking targets and path are determined by selecting the sequence of IBTs that minimizes the resources (inputs and outputs) adjustment cost (i.e., improvement amount) between ports.

Figure 1.

Framework of proposed method.

3.1. Formulation of Benchmarking Network

All DMUs are stratified into several layers according to their efficiency scores, so that the evaluated DMU, which wants to select its benchmarking target, can gradually select IBTs using the DMU stratification method.

Definition 1.

DMU stratification: This process stratifies all DMUs into several layers according to their efficiency score, utilizing the stratification DEA model introduced by Seiford and Zhu (2003) [31]. Park and Sung [8] employed this stratification DEA model to select benchmarking targets in a step-by-step manner. The DMU stratification is conducted according to the following algorithm:

- Step 1: Set , and is the set of all DMUs.

- Step 2: Evaluate the set of DMUs, , by model (1) to obtain the l-th-layer efficient DMUs, which is set .

- Step 3: Exclude the efficient DMUs from future DEA runs: . (If = Ø, stop.)

- Step 4: Evaluate the new subset of “inefficient” DMUs, , by model (1) to obtain a new set of efficient DMUs (the new frontier).

- Step 5: Let l = l + 1. Go to step 2.

- Stopping rule: If = Ø, the algorithm stops.

The model considers m input variables and s output variables across a total of n DMUs. and are the i-th input and r-th output values, respectively, produced by the evaluated DMU k. λj represents the weight with a value of 0 or 1 given to the j-th port’s input and output. and denote the i-th input slack and r-th output slack values, respectively.

We signify that is the DMU set in the l-th layer and that is the efficient DMU set in the i-th layer. When l = 1, the DMUs in set define the first-level efficient frontier, which might be the most efficient layer. For gradual selection of benchmarking targets based on the stratified layers, we specify that the evaluated DMU can sequentially select IBTs in each layer. For example, the evaluated DMU in can select its IBT in , which is relatively more efficient than that in , and the evaluated DMU in can select its IBT in . After stratifying DMUs, we can construct the benchmarking network for the evaluated DMU as directed graph G = (V, E). Let V = be the set of all DMUs grouped by layer, where L is the total number of layers. The set of directed edges is defined as E⊆{|} where each edge represents a possible benchmarking relationship in which DMU in layer l can be the benchmarking target of DMU in layer l − 1. An edge indicates that DMU belongs to a higher-efficiency layer than DMU and thus serves as a potential benchmark for . A single DMU may be connected to multiple benchmark candidates DMU , and conversely, a benchmark DMU may be referred by multiple lower-layer DMUs .

It should be noted that, as in Seiford and Zhu [31], the context-dependent stratification does not guarantee that DEA efficiency scores are strictly monotonic across layers. A DMU that appears in an upper layer is efficient with respect to the reduced set after removing previously identified frontiers, but its original CCR efficiency may be lower than that of some DMUs in lower layers. Consequently, the scalar efficiency measure along a stratified path may not increase monotonically.

For an illustration of the construction of a benchmarking hierarchy, consider the stylized example originally introduced [9], with additional DMUs incorporated, as shown in Table 2. This example consists of twelve DMUs, each consuming three inputs and yielding one output. This example is a generic pedagogical illustration of the model’s procedure and the industry-specific validation of the FW-MLBP framework is carried out using real data from international container terminals in Section 4.

Table 2.

Illustrative example dataset for constructing the benchmarking network.

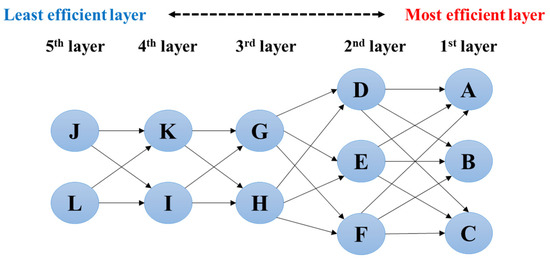

When the DMU stratification method is applied to the data in Table 2, the DMUs are grouped into five efficiency layers as follows: (most efficient, 1st layer) = {A, B}, = {E, F}, = {C, D}, = {G, H}, = {K}, = {I}, and (least efficient, 7th layer) = {J, L}. In this hierarchy, DMUs in the lowest efficiency layer (e.g.,) can identify IBTs by sequentially referencing DMUs in the upper layers (, , , , , ). Since each layer may contain multiple DMUs, various stratified benchmarking paths can be formed for a given evaluated DMU. For instance, if DMU L is selected as the evaluated DMU, the benchmarking network can visualize as directed network, as shown in Figure 2, where each directed edge represents a feasible step to a more efficient layer. This full-sized benchmarking network includes all of the 16 possible alternative benchmarking target sequences from the evaluated DMU (L) to the UBTs (A or B).

Figure 2.

Benchmarking network of illustrative example data of Table 2.

3.2. Selection of Optimal Stepwise Benchmarking Targets

Park and Sung [8] and Park [32] argued that if a firm is identified as inefficient, the most effective method for selecting a benchmarking target is to choose the firm that minimizes the required improvement in inputs and outputs from the perspective of resource utilization. To reflect this, this study utilized the concept of input/output improvement minimization when selecting stepwise benchmarking targets. That is, the stepwise benchmarking of an inefficient DMU is designed to select a target that minimizes the resource improvement.

Port resources such as loading/unloading machinery, berth areas, and container-handling equipment are capital-intensive and closely interconnected with other infrastructure. Consequently, substantial financial investment and time are required to optimize them. Key components, for example, berth length and yard capacity, are inherently inflexible, making them difficult to scale up or down freely. Such elements are thus categorized as uncontrollable resources. In contrast, machinery such as cranes or conveyors offers operational flexibility, enabling easier adjustments in capacity. These types of resources can be classified as controllable. By distinguishing between these two categories, stakeholders can prioritize scalable improvements while respecting infrastructural constraints.

In our framework, these differences are encoded via feasibility coefficients assigned to each input and output. A coefficient close to 0 indicates that a resource is effectively fixed in the short to medium term (e.g., capital-intensive infrastructure such as berth length or total yard area), whereas a coefficient close to 1 indicates a relatively flexible resource that can be adjusted through purchases, leases, or reallocation (e.g., cranes and yard transporters). Intermediate values represent partially controllable resources whose effective capacity can be improved by operational measures such as extended operating hours, personnel reallocation, or process redesign (e.g., CFS area). Thus, the feasibility coefficients act as policy parameters that reflect managerial judgments about the relative ease, cost, and time required to adjust each resource.

We propose the Feasible-Weighted Multi-Layer Benchmarking Path optimization (FW-MLBP) model to determine stepwise benchmarking targets that minimize resource improvement in consideration of the characteristics of port resources (controllable and uncontrollable resources). The FW-MLBP is an optimization model based on mixed-integer linear programming (MILP).

The FW-MLBP model’s notation is as follows.

- Sets and Indices

- : Set of DMUs belonging to layer l (l = 1, …, L)

- : Set of efficient DMUs in layer l.

- : DMU j located in layer l.

- : DMU k located in upper layer l − 1.

- Parameters

- : Input i of DMU j in layer l.

- : Output r of DMU j in layer l.

- : Output r of DMU j in layer l.

- : Feasible coefficient of input i, taking a value between 0 (hard to improve) and 1 (fully improvable)

- : Feasible coefficient of output r, taking a value between 0 (hard to improve) and 1 (fully improvable)

- : Min and max values of input i across all DMUs.

- : Min and max values of output r across all DMUs.

- Decision variable

The objective is to minimize the total input improvement cost, as normalized per unit and weighted by feasibility coefficients, when lower-layer DMUs benchmark progressively against higher-layer efficient DMUs:

To ensure that the selected benchmarking path is feasible and continuous, the model imposes the following four constraints:

- Each DMU selects exactly one IBT in the next upper layer:

- 2.

- If a DMU is selected as part of the path, it must also connect to a DMU in the next layer:

- 3.

- The final benchmarking target must be the designated FBT in the top layer:

- 4.

- Binary nature of decision variables:

This model ensures that an inefficient DMU can select a stepwise benchmarking path through a stratified structure of efficient DMUs, thus minimizing the effort required to improve performance in practice when considering controllable and uncontrollable inputs and outputs. It serves as a practical decision-support tool for implementation of achievable benchmarking strategies in multi-stage efficiency improvement settings.

To demonstrate the proposed FW-MLBP model, we applied it to the illustrative dataset described in Table 2. In this example, DMU L, located in the lowest efficiency layer, aims to benchmark the most efficient DMU B through a sequence of IBTs. Each DMU is characterized by a three-dimensional input vector . Let and be the controllable resources, and let be the uncontrollable resource. A feasibility coefficient of 1 is assigned to controllable resources, while a value of 0.2 is assigned to uncontrollable resources, indicating that the potential for improvement is limited to approximately 20%. In the example of Table 2, the Input 2 corresponds to such an uncontrollable input: it is not entirely immutable but can be improved only to a limited extent compared with other resources such as Input 1 or Input 3. If a resource is completely uncontrollable and cannot be improved at all, its feasibility coefficient should be set to 0.

Using the proposed model, the optimal stepwise benchmarking path for DMU L is determined as L → K → H → E → B, L → K → H → F → B, L → I → H → E → B, and L → I → H → F → B. These paths minimize the total input and output resource improvement cost, calculated as the weighted sum of normalized adjustments between adjacent DMUs in the path. The total cost incurred along these paths is approximately 0.63.

To validate the optimality of the proposed method, we further enumerated all feasible stepwise paths from DMU L to B, selecting one IBT from each intermediate layer. Table 3 summarizes the total input reduction costs of all of the valid benchmarking paths to DMU B. As indicated, the proposed MILP model successfully identifies the path with the lowest cumulative input adjustment, which confirms the model’s ability to derive the most practical and resource-efficient benchmarking strategy among all possible alternatives.

Table 3.

Comparison of benchmarking paths from DMU L to FBT.

The proposed FW-MLBP model optimizes the feasibility-weighted resource adjustment cost along the path, rather than enforcing monotonicity of the conventional DEA efficiency index at every step. As a result, for certain datasets, a cost-minimizing path may include an intermediate DMU whose CCR score is slightly lower than that of the previous DMU, as pointed out by the reviewer. We now explicitly recognize this as a limitation of the stratification-based framework and clarify that ‘upper layers’ are defined in the sense of context-dependent DEA, not as a strict total order of scalar efficiency scores.

4. Port Application

In a case study, we applied our proposed method to actual port terminal data in order to select the optimal stepwise benchmarking path of an inefficient port by minimizing the total improvement amount of resources when considering resource characteristics. The data sources for 30 container port terminals were gathered from the Containerization International Year Book, excluding incomplete data. Though this data is not recent, it effectively characterized the port and was sufficient for application of the proposed method. The berth length (m), total area (m3), Container Freight Station (CFS), number of cranes, and number of yard transporters were used as inputs, while the number of complete loadings and unloadings (TEU) were used as outputs for the port’s efficiency evaluation. Container gantries, yard gantries, quay cranes, floating cranes and mobile cranes were included in the number of cranes, and straddle carriers, forklifts, reach stackers, top lifters, yard tractors and yard trailers were included in the number of yard transporters; empty containers and full containers were included in the number of loaded and unloaded containers, respectively.

We set the berth length and total area as uncontrollable resources, because these could be regarded as high-cost and long-term improvements. This means that the berth length and the yard area could be regarded as useful resources for efficiency measurement but were inappropriate resources for benchmarking, because they could not be reduced or expanded in a practical port environment, due to the high cost incurred. Accordingly, their feasible coefficients were set to zero (i.e., = 0, = 0). Although the CFS is a physical facility, its operational efficiency can be adjusted to some extent by controlling its operating hours and the allocation of internal personnel. For this reason, the CFS is considered a partially controllable resource. So, we assigned it a partially feasible coefficient of 0.3 (i.e., = 0.3). By contrast, the number of cranes and number of yard transporters were classified as controllable resources, because their numbers could be increased through mid-to-long-term purchases or leases, making them comparatively easy to manage. The feasible coefficient assigned to the number of cranes and the number of yard transporters was set to 1 (i.e., = 1, = 1).

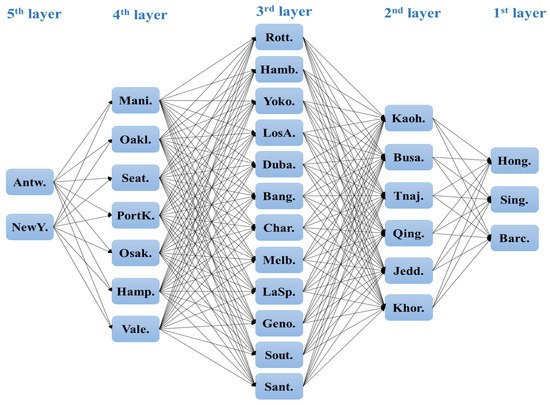

The descriptive statistics for the inputs and outputs of the 30 ports are listed in Table 4, and the benchmarking network is visualized in Figure 3. If Antw. (in the 5th layer) is selected as the evaluated port and Hong. (in the 1st layer) is the FBT, there are a total of 504 possible paths that can be reached step-by-step. If the FBT is not specifically set and the goal is to benchmark against any one of the potential FBTs in the final layer (the 1st layer), the total number of reachable paths for Antw. is 1260. From the numerous step-by-step benchmarking targets and paths reachable by Antw., the IBTs were selected by applying the FW-MLBP model, which minimizes the total amount of resource improvements.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics for inputs and outputs used.

Figure 3.

Benchmarking network of Antw. port.

We set Antw. as the evaluated port that wishes to benchmark, and explored the optimal stepwise benchmarking targets and paths that minimize total resource improvement. Considering the characteristics of port resources, let us explore the stepwise benchmarking targets and paths from two perspectives. First, we calculated the stepwise benchmarking targets for Antw. port under the assumption that all of the resources (berth length, total area, container freight station, number of cranes, number of yard transporters, complete loadings/unloadings) are fully controllable. Second, we calculated the stepwise benchmarking targets under the assumption that some resources (the berth length and total area) are realistically uncontrollable, while another resource (container freight station) is partially controllable. We then compared the results of these two.

First, we assumed that all of the resources are controllable. That is, was assigned as [0, 0, 1, 1, 0.3], and was assigned as [1, 1]. These values were chosen to reflect a typical container terminal context, where berth length and total yard area are largely fixed in the short to medium term, the CFS can be improved to a limited extent through operational adjustments, and the numbers of cranes and yard transporters can be modified through investment and leasing decisions. In practice, the feasibility coefficients can be elicited from port authorities and planners and may differ across terminals depending on local investment constraints and policy priorities. Among the stepwise benchmarking targets for Antw. port, the targets/path that could achieve the minimum optimal resource improvement was Oakl. → Sout. → Qing. → Barc. That is, Antw. port should select Oakl., which is in the 4th layer, as the first IBT, and next Sout., which is in the 3rd layer, and next Qing., which is in the 2nd layer, and finally Barc., which is in the 1st layer. At this time, the total amount of resources that Antw. port must improve, based on the normalized value, became 1.428. The experimental results showing the top 10 and bottom 10 targets and paths for minimization of resource improvement, among the total 1260 stepwise benchmarking paths that Antw. port could select, are summarized in Table 5. Conversely to minimizing resource improvement, the inefficient stepwise benchmarking targets/path for Antw. port that maximized resource improvement became Vale. → Rott. → Khor. → Hong., and the normalized value for the total amount of resources that Antw. port must improve was about 3 times greater (1.428:4.313) than that for the path that minimizes resource improvement.

Table 5.

Stepwise benchmarking targets and paths of Antw. port in consideration of all resources being controllable.

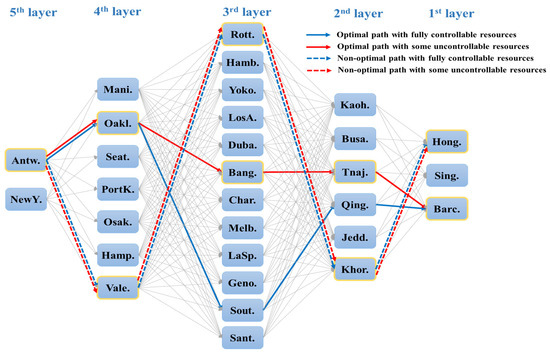

Next, we explored the stepwise benchmarking targets for Antw. port by considering berth length and total area as uncontrollable resources, CFS as a partially controllable resource, and the remainder as controllable resources. That is, was assigned as [0, 0, 1, 1, 0.3] and was assigned as [1, 1]. The stepwise benchmarking targets/path that achieved the minimum resource improvement for Antw. port was Oakl. → Bang. → Tanj. → Barc. Specifically, Antw. port should select Oakl. (in the 4th layer) as the first IBT, followed by Bang. (in the 3rd layer), then Tanj. (in the 2nd layer), and finally Barc. (in the 1st layer). The total normalized resource improvement required for Antw. port along this optimal path was 0.349. The experimental results, summarizing the top 10 and bottom 10 targets and paths for minimization of resource improvement among the total 1260 stepwise benchmarking paths available to Antw. port, are presented in Table 6. Among the total 1260 paths, the inefficient benchmarking targets/paths that maximized resource improvement were Vale. → Rott. → Khor. → Hong, with a total normalized resource improvement value of 3.055. This indicates that the total amount of resources Antw. port needed to improve was approximately 8.7 times greater (0.349:3.055) than that for the minimum resource improvement path. The optimal and non-optimal paths of Antw. port are illustrated in Figure 4.

Table 6.

Stepwise benchmarking targets/paths of Antw. port in consideration of some resources being uncontrollable.

Figure 4.

Optimal and non-optimal paths according to resource controllability.

It is worth noting that the FW-MLBP framework can be applied under alternative feasibility-coefficient scenarios. For example, if port authorities regard berth length or yard area as partially adjustable in the long run, small positive feasibility values can be assigned to these resources, which would reweight the adjustment cost and may change the relative attractiveness of some benchmarking paths. Similarly, treating CFS as more or less controllable would shift the balance between infrastructure-related and equipment-related improvements. Therefore, the feasibility coefficients should be interpreted as policy levers that can be tuned to reflect local conditions, and the resulting stepwise paths should be analyzed in conjunction with the assumed feasibility profile.

We computed the burden (share) of improvements by resource to identify which resource demanded the largest adjustment when Antw. port followed the optimal benchmarking path. Specifically, at each layer, we summed the required improvement for each resource and divided it by the total improvement across all resources to obtain its share. Table 7 reports the results: the yard transporters showed an improvement intensity of 0.95 and accounted for 50.7% of the total, indicating they were the most demanding resource for Antw. port.

Table 7.

Share of improvements by resource.

From the application of the proposed method to actual port terminals, we learned that the proposed method can provide more practical benchmarking information than a general DEA approach, in that the proposed method can select more rational benchmarking targets by considering the minimization of resource improvement; this is crucial, given that many resources in the port industry are long-term and cost-intensive. For this reason, we expect that the proposed method will lead to more practical and effective benchmarking target selections and efficiency improvement strategies for port terminals.

5. Concluding Remarks

This paper presented a practical framework, namely the feasibility-weighted multi-layer benchmarking path optimization (FW-MLBP) model, which is a mixed-integer linear programming (MILP)-based method that embeds feasibility weights to reflect differences in resource controllability and guides inefficient ports to sequentially select attainable intermediate benchmarks. In experiments on 30 container terminals, the Antw. port case showed that under the all-controllable assumption, the path Oakl. → Sout. → Qing. → Barc. attained the minimum adjustment cost, with a normalized total improvement of 1.428, thereby reducing the burden threefold compared with the worst path, Vale. → Rott. → Khor. → Hong, at 4.313. Under a realistic scenario that accounted for uncontrollable resources and a partially controllable resource, the optimal path still emerged, with a total of 0.349, about 8.7 times lower than the worst case at 3.055, demonstrating that modeling resource controllability is decisive for path quality. The per-resource analysis identified yard transporters as the primary bottleneck, with improvement intensity 0.95 and improvement share 50.7%, thus informing concrete priorities such as capacity expansion, layout redesign, and operating-hour adjustments.

From a managerial standpoint, the FW-MLBP model is intended to support medium-term strategic and operational planning for port authorities. In a given planning horizon, decision makers can first estimate efficiency scores via DEA, construct the multi-layer benchmarking network, and then apply the FW-MLBP model to derive a stepwise sequence of intermediate benchmarks that minimizes feasibility-weighted resource adjustments. These intermediate targets can be aligned with planned investment stages, such as phased acquisitions of yard equipment or gradual process improvements in CFS operations. As demand conditions, technology, and regulatory constraints evolve, the DEA model and the FW-MLBP analysis can be re-estimated in a rolling-horizon fashion, allowing port authorities to update the benchmarking path and adjust their improvement strategies while maintaining a clear view of the long-term efficiency frontier.

The proposed methodology, notwithstanding its great utility, does not consider the number of benchmarking steps necessary for an inefficient Decision Making Unit (DMU) to reach the final benchmarking target. In an actual inefficient organization, the number of benchmarking steps can be an important decision factor: if there are too many stepwise benchmarking targets, the benchmarking task might incur significant practical difficulty for the DMU. Moreover, the present analysis is static: it is based on a single cross-section of port data and does not explicitly account for demand uncertainty, time-phased budget constraints, or technological change. Future research could extend the FW-MLBP framework to a dynamic setting by combining it with rolling-horizon DEA, demand forecasting, or capital-budgeting models, and by explicitly optimizing not only the composition of the benchmarking path but also the number and timing of steps. If practitioners require that efficiency scores strictly increase along the path, an extended version of the MILP can be formulated by adding additional constraints that impose monotonicity of a chosen efficiency index at each step. Developing and testing such a constrained variant is left as a topic for future research.

Overall, the FW-MLBP model complements existing stepwise benchmarking and network-based DEA approaches by embedding feasibility weights for port resources and by using an MILP-based global optimization scheme to derive practically implementable, stepwise benchmarking paths for inefficient terminals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P.; Methodology, J.P.; Software, J.P.; Validation, J.P.; Formal analysis, H.K. and J.P.; Investigation, J.P.; Resources, J.P.; Data curation, H.K. and J.P.; Writing – original draft, J.P.; Writing – review & editing, J.P.; Visualization, J.P.; Supervision, J.P.; Project administration, J.P.; Funding acquisition, J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the 5th Educational Training Program for the Shipping, Port and Logistics from the Ministry of Ocean and Fisheries.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available because they were obtained under a confidentiality agreement with Busan Port Authority in the Republic of Korea. No additional data can be shared due to these contractual restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Spendolini, M.J. The Benchmarking Book; AMACOM: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Donthu, N.; Hershberger, E.K.; Osmonbekov, T. Benchmarking marketing productivity using data envelopment analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 1474–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.; Droge, C. An integrated benchmarking approach to distribution center performance using DEA modeling. J. Oper. Manag. 2002, 20, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.S.; Lu, L.Y.Y.; Lu, W.M.; Lin, B.J.Y. A survey of DEA application. Omega 2013, 41, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emrouznejad, A.; Yang, G.-L. A survey and analysis of the first 40 years of scholarly literature in DEA: 1978–2016. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2018, 61, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotova Čiković, K.; Martinčević, I.; Lozić, J. Application of Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) in the sustainable supplier selection: A bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, S.A.; Song, H.S.; Kim, Y.A.; Namn, S.H.; Kang, S.C. A method of stepwise benchmarking for inefficient DMUs based on the proximity-based target selection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 11595–11604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Sung, S.I. Integrated approach to construction of benchmarking network in DEA-based stepwise benchmark target selection. Sustainability 2016, 8, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, W.W.; Seiford, L.M.; Tone, K. Introduction to Data Envelopment Analysis and Its Uses: With DEA Solver Software and References; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Talluri, S. A benchmarking method for business-process reengineering and improvement. Int. J. Flex. Manuf. Syst. 2000, 12, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alirezaee, M.R.; Afsharian, M. Model improvement for computational difficulties of DEA technique in the presence of special DMUs. Appl. Math. Comput. 2007, 186, 1600–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Nijkamp, P. A stepwise-projection data envelopment analysis for public transport operations in Japan. Lett. Spatial Resour. Sci. 2011, 4, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.J.; Yu, S.J. Benchmark optimization and attribute identification for improvement of container terminals. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 201, 568–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanassoulis, E. A comparison of data envelopment analysis and ratio analysis as tools for performance assessment. Omega 1996, 24, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-C.; McGinnis, L.F. Reconciling ratio analysis and DEA as performance assessment tools. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 178, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayuth, Y.; Roll, Y. Port performance comparison applying data envelopment analysis (DEA). Marit. Policy Manag. 1993, 20, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Budría, E.; Diaz-Armas, R.; Navarro-Ibáñez, M.; Ravelo-Mesa, T. A study of the efficiency of Spanish port authorities using data envelopment analysis. Int. J. Transp. Econ. 1999, 26, 237–253. [Google Scholar]

- Park, R.-K.; De, P. An alternative approach to efficiency measurement of seaports. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2004, 6, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, C.P.; Athanassiou, M. Efficiency in European seaports with DEA: Evidence from Greece and Portugal. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2004, 6, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mithun, J.S.; Song, J.-Y. Performance based stratification and clustering for benchmarking of container terminals. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 5016–5022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichou, K. A two-stage supply chain DEA model for measuring container-terminal efficiency. Int. J. Shipp. Transp. Logist. 2011, 3, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lim, S.; Bae, H. DEA-based port efficiency improvement and stepwise benchmarking target selection. Information 2012, 15, 6155–6172. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.N.; Nguyen, P.H.; Nguyen, T.L.; Nguyen, T.G.; Nguyen, D.T.; Tran, T.H.; Phung, H.T. A two-stage DEA approach to measure operational efficiency in Vietnam’s port industry. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Ma, D.P.; Gan, G.Y. Context-dependent data-envelopment-analysis-based efficiency evaluation of coastal ports in China based on social network analysis. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2023, 31, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danladi, C.; Tuck, S.; Tziogkidis, P.; Tang, L.; Okorie, C. Efficiency analysis and benchmarking of container ports operating in lower-middle-income countries: A DEA approach. J. Shipp. Trade 2024, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, J.; Yang, J.; Ma, X.; Yuan, H. Investigating the efficiency of container terminals through a network DEA cross efficiency approach. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2024, 53, 101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakalidis, C.; Liani, E.; Tsakalidis, G.; Vergidis, K.; Madas, M. Benchmarking Efficiency in Mediterranean Ports: A DEA-Based Analysis of Connectivity and Operational Performance. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, Porto, Portugal, 4–6 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ibeh, F. Comparative analysis of container ports performance in West Africa. J. Shipp. Trade 2025, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Luo, M.; Yang, D. Are efficient ports for port operators also those for shipping companies? A meta-frontier analysis of global top 80 container ports. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2025, 263, 107616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Emrouznejad, A.; Pratap, S. Achieving net zero: Enhancing maritime port efficiency through multi-objective integrated DEA-MORCOS. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2025, 22, 101597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiford, L.M.; Zhu, J. Context dependent data envelopment analysis measuring attractiveness and progress. Omega 2003, 31, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. Combined Text-Mining/DEA method for measuring level of customer satisfaction from online reviews. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 232, 120767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).