Abstract

Based on explicit computations, various concepts of discrete time scattering theory are reviewed, discussed, and illustrated. The dynamics take place on a discrete half-space. All operators are represented graphically. The expressions obtained for the wave operators lead to an easily visualized interpretation of Wold’s decomposition, a seminal result of operator theory. This work has a clear pedagogical orientation, with the aim of providing explicit formulas and graphical representations for operators which are usually only known to exist.

MSC:

47A40

1. Introduction

Scattering theory is a well-developed theory that provides asymptotic information about the evolution of dynamical systems as time approaches to plus or minus infinity. If the time parameter is continuous, the evolution is mainly driven by unitary groups of the form with H a self-adjoint operator on a Hilbert space, while if the time parameter is discrete, one often considers unitary groups of the form with U a unitary operator.

In this pedagogically oriented paper, we provide an example of a discrete time evolution system that allows for all computations to be performed explicitly. As a consequence, various outcomes of scattering theory can be easily visualized, and several concepts can be concretely discussed. Notions such as the invariance of certain subspaces under the evolution, the commutation relation of the scattering operator with the free evolution, and the chain rule, can all be represented in pictures and checked graphically. We also take the opportunity of obtaining explicit expressions to illustrate a fundamental result of operator theory: Wold’s decomposition. This result says that any isometry can be decomposed into the sum of a unitary operator and a collection of shift operators. For all wave operators computed in this paper, we directly exhibit this decomposition, without any further effort.

Let us note that visualizing scattering systems is not a new concept, it appeared for example already in [1,2], see also the references therein. However, to the best of our knowledge, this convenient tool has never been used for the wave operators, but mainly for the scattering operator. In addition, its use for illustrating Wold’s decomposition seems to be original.

We now describe more precisely the content of this paper. In Section 2, we recall the main idea of discrete time scattering theory and introduce the wave operators and the scattering operator. These operators will play a prominent role in the rest of the paper. We then immediately describe the specific scattering model we focus on. The framework consists of the lattice representing a discrete two-dimensional half-space. Various unitary evolution groups are defined in this space by exhibiting the action of these operators on a natural basis of the corresponding Hilbert space . Using these concrete operators, explicit expressions and graphical representations are provided for the wave operators and for the corresponding scattering operators.

In Section 3, we recall a few general properties of the wave operators and exemplify them using our explicit models. Here, the intertwining relation satisfied by the wave operators plays a crucial role. We discuss the ranges of the wave operators and their cokernels. Special emphasis is placed on the invariance of these subspaces with respect to the evolution groups. The properties of the scattering operator are also discussed. Even though the wave operators are highly non-trivial, the scattering operators are quite simple. This simplicity is mainly due to their commutation relationship with the free evolution group, as explained in this section.

With numerous explicit expressions for the wave operators available, we would like to make the best use of them to illustrate a seminal result valid for all isometries: Wold’s decomposition. At no cost, this abstract result can be clearly visualized. In Section 4 we recall this theorem and explain how the previous expressions can be understood in this context. This section also supports our strong belief that the interaction between scattering theory and abstract operator theory is not only interesting but also fruitful: the former provides many interesting and meaningful examples while the latter organizes various results and broadens perspectives. In summary, our aim is to illustrate various concepts of scattering theory with examples and pedagogical explanations.

2. Discrete Time Scattering Theory and Explicit Expressions

Let us start by recalling the main question and ideas of scattering theory, and provide some important definitions. We concentrate on discrete time scattering theory. A related recent work based on discrete time evolution groups can be found in [3].

Given a unitary operator U on a Hilbert space , and given an element , can one find an auxiliary unitary operator and two elements such that the following asymptotic estimates hold:

Equivalently , these conditions also read

Thus, if the limits exist in the sense mentioned above, we set

where stands for a strong limit and corresponds to the limit defined in (1). Note that other notations are also used for in the literature, and even the convention for the ± sign depends on the authors. We then infer that the following relations hold:

These equalities mean that the evolution can be approximated by the evolution for if and only if f belongs to the range of the so-called wave operators . Clearly, this approach is interesting only if is simpler than U. In particular, is often assumed to be an operator with an absolutely continuous spectrum.

Let us also emphasize that not only the ranges of the wave operators are of interest, but their orthocomplement also contains interesting information. Indeed, any element of orthogonal to the range of cannot be described asymptotically by the evolution defined by . This means that these elements either do not scatter, or scatter with an asymptotic evolution which is not well approximated by . Both situations can take place, as we shall see in the models introduced below.

2.1. Initial Model

In this and the following two subsections, we introduce the models (initially inspired by [4] (Ex. 5.12)) and provide the main results relevant to scattering theory. The configuration space for our models is the discrete half-space , with . Accordingly, the description takes place in the complex Hilbert space , endowed with the standard orthonormal basis

defined by if and , and otherwise. For any , the scalar product of these two elements is given by

while the norm on this Hilbert space is defined by .

We consider two unitary operators and defined by their action on the standard basis, namely

and

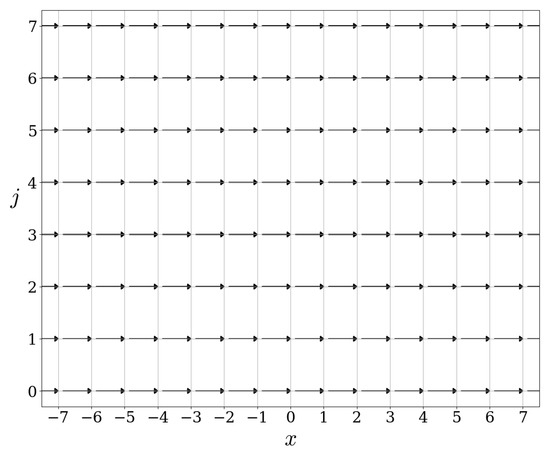

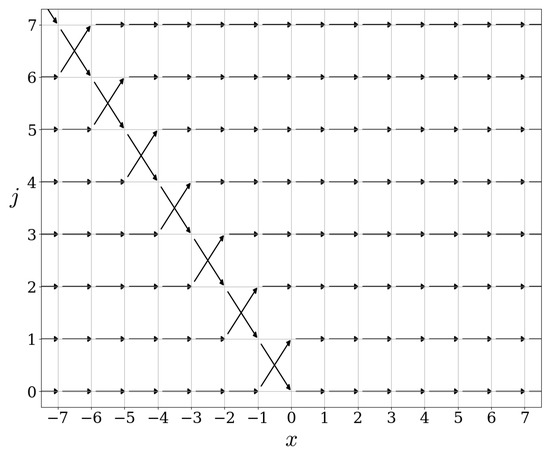

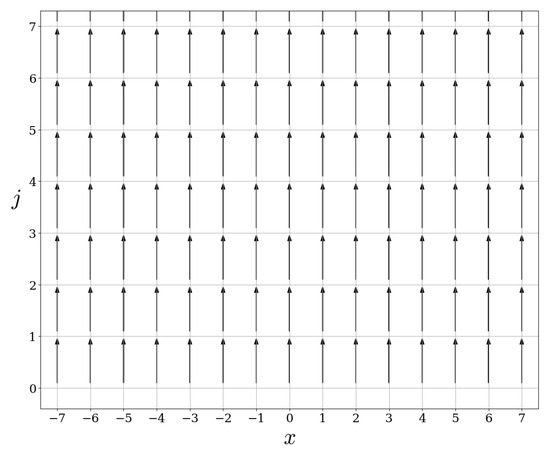

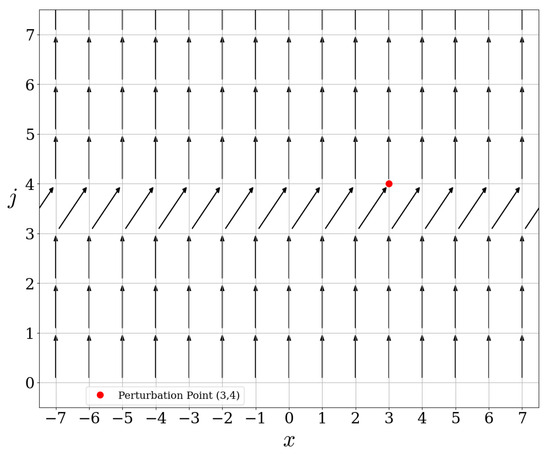

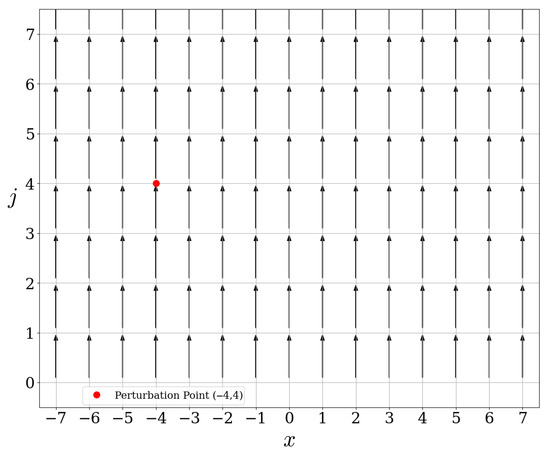

We refer to Figure 1 and Figure 2 for graphical representations of the actions of these operators.

Figure 1.

Action of .

Figure 2.

Action of .

Remark 1.

Let us explain how to read the figures provided in this paper: each point on the lattice can be associated to an element of the basis introduced in (2). If A corresponds to the operator represented in a figure, then an arrow starting at and ending at means . A black dot at means that , or in other words the operator A acts as the identity on the element of the basis of .

By using the scalar product on and the relations and it follows that while

Given and , let us consider the wave operators defined by

By linearity, it is enough to consider the limits , which can be computed explicitly by using Figure 1 and Figure 2. One then gets:

and

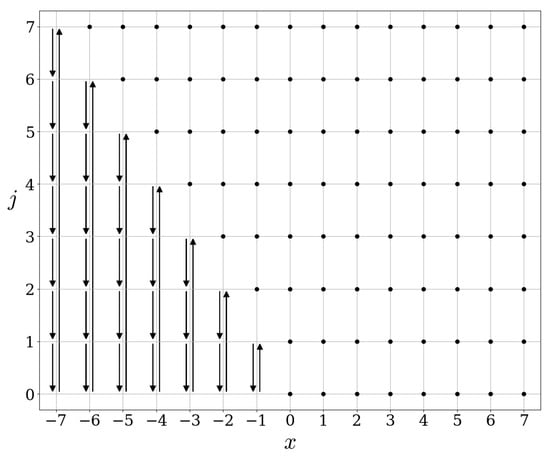

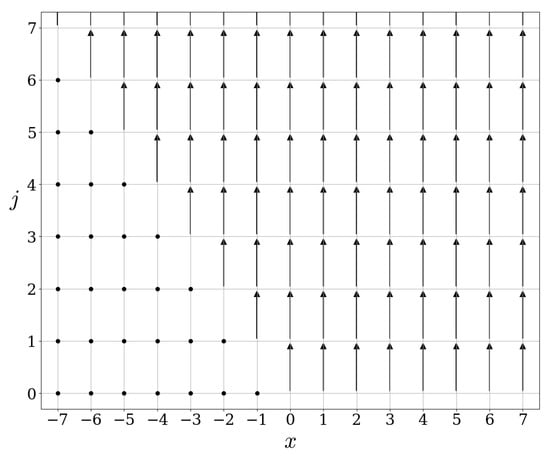

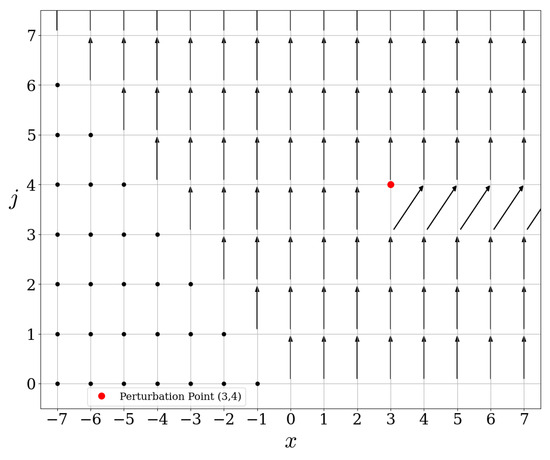

We refer to Figure 3 and Figure 4 for graphical representations of the actions of these operators.

Figure 3.

Action of .

Figure 4.

Action of .

Note that that the existence of the operators and their precise expressions can be inferred rather informally. However, for completeness we provide a precise proof in Lemma A1, which has been transferred to Appendix A in order to retain the flow of the presentation.

Recall now that the range of these operators is defined by

The method for deducing the range from a figure is explained in the following remark:

Remark 2.

On a figure representing an operator A, the range of the operator A corresponds to the ending points of all arrows together with the black dots. The cokernel of A can be identified with the points that are neither the ending point of any arrow nor a black dot.

By taking this remark into account one readily observes that while . The orthocomplement of the range is called the cokernel. By a closer inspection at these subspaces one obtains and

with

Here, means the subspace of generated by the mentioned elements.

Note that for these operators, their kernel and their cokernel can also be obtained by analytic formulas, namely (see for example [4] (Prop. 2.9))

and

where the adjoint can be computed from the equality

In order to use the above formulas, we firstly deduce from (3), (4), and (8) that

and that

Based on these expressions we can then confirm the following:

Lemma 1.

One has , , and

The proof of this statement is provided in Appendix A. Now, with the already computed expressions for and , the next object of scattering theory to be introduced is the scattering operator . It is defined by the product

Note that the product of two operators can be computed according to the following remark:

Remark 3.

If A and B correspond to operators represented in two figures, the action of the product on the element can be obtained by looking at the action of B on where is given by the relation . The resulting element represents the image of by the product .

Based on this remark, one can obtain the action of the scattering operator on the orthonormal basis, namely

By a direct computation, one observes that this operator is not unitary and that

As for the wave operators, the scattering operator is only an isometry (this fact is discussed in Section 3). The action of is represented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Action of .

2.2. Perturbed Model 1

We now introduce a perturbation to the model studied in the previous section. For that purpose, we use the bra-ket notation, namely for any we set

The perturbation is localized around the position in the configuration space, on the right of the diagonal .

We fix with and . The new unitary operator is defined by

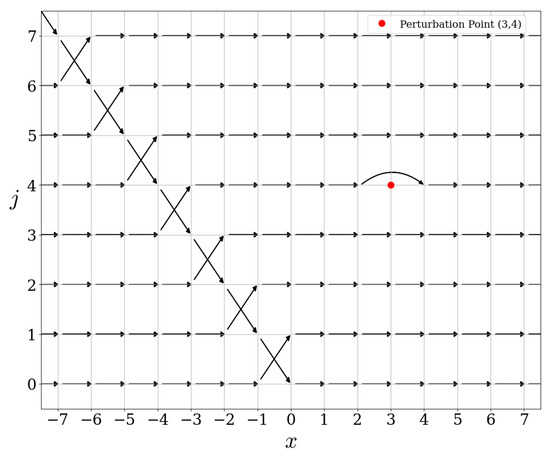

We refer to Figure 6 for the graphical representation of the action of this operator.

Figure 6.

Action of .

By a direct computation, one gets

and

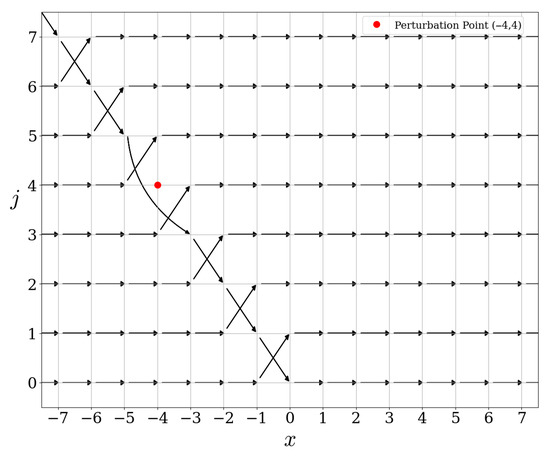

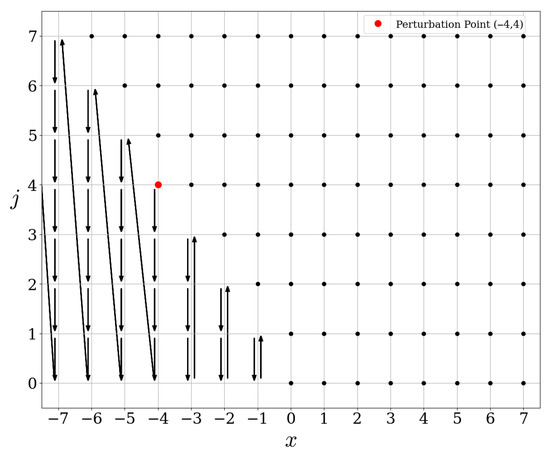

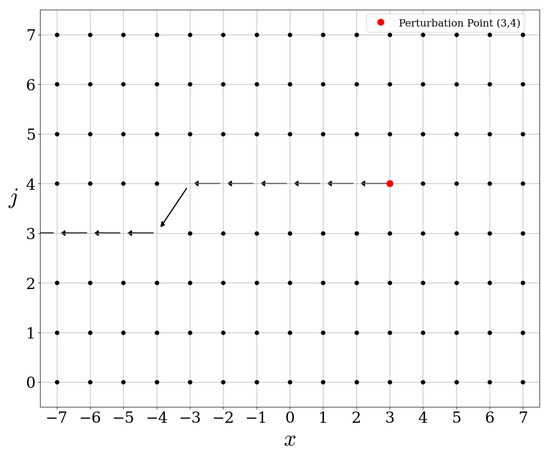

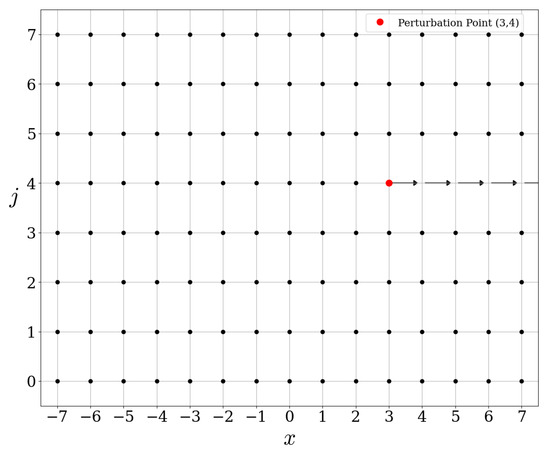

We refer to Figure 7 and Figure 8 for the actions of these operators.

Figure 7.

Action of .

Figure 8.

Action of .

From these results, one observes that the cokernels of these two operators are given by and , with defined in (5). For the adjoint of we find

Then, the scattering operator is given by

As before, one observes that

The action of is represented in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Action of .

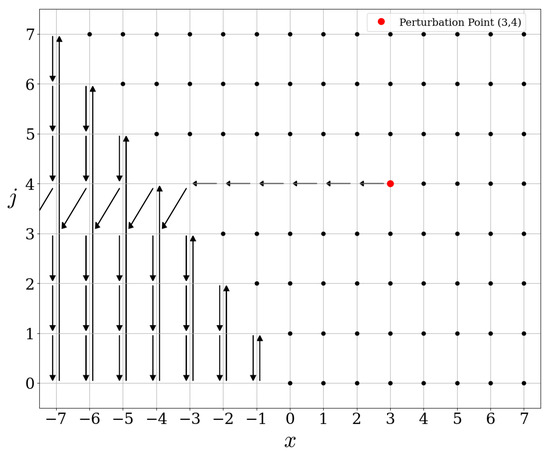

2.3. Perturbed Model 2

We shall again perturb the initial model, but this time the perturbation is located on the diagonal. More precisely, we fix with and define the new unitary operator by

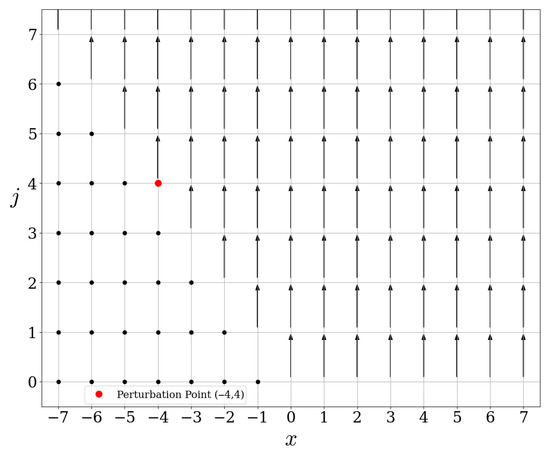

We refer to Figure 10 for the action of this operator.

Figure 10.

Action of .

By a direct computation, we find

and

We refer to Figure 11 and Figure 12 for the actions of these operators.

Figure 11.

Action of .

Figure 12.

Action of .

This gives and , with defined in (5). For the adjoint of one gets

Then, the scattering operator is given by

which has an action similar to the one of , see Figure 13 and the comment in the next section.

Figure 13.

Action of .

3. Scattering Outcomes

In this section, we start by recalling a few general properties of scattering systems, and then illustrate these properties on the models introduced in the previous section.

3.1. General Properties

Let us assume that the following wave operators exist:

where are unitary operators on a Hilbert space . Most of the subsequent properties are based on the intertwining relation. More precisely, for any one has

This general relation can be deduced from (15), by a change of variable in the limits.

From these relations, one first deduces the invariance of the range of the wave operators, and accordingly the cokernel of these operators. Indeed, since by definition one has

where we have used the fact that . These equalities mean that

Since , one readily deduces that

Another general property which follows from the intertwining relation is the commutation relation between the scattering operator and the free evolution . More precisely one has

leading to the equality . As will be illustrated using the models, the commutation relation implies a very strong constraint on the form of the scattering operator.

We finally mention one final property related to the wave operators: the chain rule. It says that if one considers three unitary operators and if the wave operators exist for two pairs, then they also exist for the third pair, provided a certain compatibility condition (ordering) is satisfied, see Section 3.2.3 for a precise statement. We will illustrate this rule explicitly on our examples.

3.2. Illustration on the Models

We now come back to the models of Section 2 and illustrate the preceding relations.

3.2.1. Invariance of Cokernels

Firstly, the invariance of the cokernels can be checked by hand. Indeed, recall that , with defined in (5), and that

One can then check that , that , and that . Similarly, one has , and . In addition, the following invariance also holds: with

As explained in the Introduction, elements in the cokernel of the wave operators cannot be described asymptotically by the evolution group generated by . This fact becomes clear when we consider for . Indeed the action of on , of on , and of on are equivalent to the action of a shift operator on , but the iterated actions , , and on these respective domains bear no relations to when , see Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 6 and Figure 10. This explains why the cokernel of is not empty, for . On the other hand, when , the asymptotic evolution generated by matches the asymptotic evolution generated by , ensuring the existence of the wave operators with nothing in the cokernel except the bound states of . As a result of this asymmetry in the ranges of and , the rather common equality does not hold for our examples. The main consequence is that the scattering operator is not unitary, while this property holds when the ranges are equal.

We also observe that the 1-dimensional subspace spanned by is left invariant by the action on , and the 1-dimensional subspace spanned by is left invariant by . These subspaces correspond to bound states of the operators and , respectively. Clearly, the evolution on these subspaces has nothing to do with the evolution generated by , and must therefore belong to the cokernels of and , respectively.

3.2.2. Commutation Between Scattering Operators and Free Evolution

Let us now illustrate the commutation relation of the scattering operators with the free evolution . This commutation relation is visible in the figures. Indeed, the action of on is independent of , for , see Figure 5, Figure 9 and Figure 13. Since the action of is precisely a shift on the x-variable, the commutation relation holds automatically. In fact, any operator commuting with must have an action on which is independent of x.

As already observed for the perturbed model 2, the equality holds, even if and are different. Clearly, this equality has a profound consequence: by just knowing the scattering operator, it is not possible to distinguish between the initial scattering system modeled by the evolution and the perturbed evolution driven by . Thus, the uniqueness of the inverse scattering problem based only on the scattering operator will not be possible for these systems. However, the prior knowledge of the existence of a bound state from and the absence of any bound state for might help for the inverse problem. We do not investigate the inverse problem any further here.

We add one final remark on the scattering operators. Clearly, the operators and differ only by a finite rank perturbation. However, the operators and are quite different, and this difference is not even compact, see Lemma 2. This feature is rather well-known in scattering theory: a small change in the initial evolution operators can lead to a drastic change in the resulting scattering operators. The perturbed model 1 is a good illustration of this phenomenon.

Lemma 2.

The difference is not a compact operator in .

The proof of this statement is provided in the Appendix A.

3.2.3. Chain Rule

Let us start by recalling the general feature of the chain rule adapted to the unitary setting: given three unitary operators , , and , and assuming that

exist, then also exists and verifies

Note that the proof of this statement is straightforward since (17) implicitly assumes that and are purely absolutely continuous operators. We now illustrate this general result based on our model.

The wave operators have already been computed in the previous section, but let us show that they can be obtained by the above product. For that purpose, one needs to compute . This can be readily computed and one obtains

We refer to Figure 14 and Figure 15 for the actions of these operators.

Figure 14.

Action of .

Figure 15.

Action of .

4. Wold’s Decomposition

Let us first introduce one notation: one sets for the shift operator acting on . On the standard basis of , this operator acts as . We also recall that an isometry W on a Hilbert space satisfies , or equivalently . In particular, is an isometry. We now state Wold’s decomposition:

Theorem 1

(Thm. V.2.1 of [5]). If W is an isometry on a Hilbert space , then there is a cardinal number α and a unitary operator U (possibly vacuous) such that W is unitarily equivalent to .

We now show that all isometries introduced in Section 2 fit well with this statement and the unitary equivalence can be implemented explicitly. We start with the operators of Section 2.1. Recall that the operator is unitary, while the operator is only an isometry, with a cokernel described by (5). Evidently, there is nothing special to say in relation to Wold’s decomposition for the operator . Still, it is interesting to observe on Figure 3 that the unitary character of is due to two distinct types of orbits: fixed points for for , and cyclic orbits otherwise.

For represented in Figure 4, the key observation is that this isometry already has a form that suits well with Wold’s decomposition. Indeed, let us provide an alternative form of the Hilbert space , namely

with

and for

Then, leaves each of these subspaces invariant, and while . Thus, in relation to Wold’s decomposition, the cardinal number is 0 for , while this cardinal number is (called “aleph-zero”, it represents the cardinality of the set ) for .

The situation for , represented in Figure 8 is quite similar: A decomposition of the Hilbert space

with defined in (19), and with and . The spaces and can be defined by following the infinite paths made of arrows, and the action of on and on is unitarily equivalent to the shift operator . As a consequence for .

On the other hand, the operator represented in Figure 7 shows a decomposition of this operator into a unitary part made of fixed points and non-trivial cycles, and one part (obtained by following the only infinite path of arrows and starting at ) unitarily equivalent to the shift operator in . Ultimately, for the operator .

Finally, the isometry represented in Figure 12 is quite similar to the operator with respect to Wold’s decomposition. On the other hand, the wave operator represented in Figure 11 is quite similar to . Indeed, this operator can be decomposed into a unitary part made of fixed points and non-trivial cycles, and one part unitarily equivalent to a shift operator in the Hilbert space . This part is again obtained by the infinite path of arrows visible in Figure 11 and starting at . As a consequence, one has for the operator .

Note that all scattering operators and the wave operators of Section 3.2.3 are also isometries, and therefore the same observations with respect to Wold’s decomposition also hold for them. We leave this simple exercise for the interested reader.

Remark 4.

It is worth noting that Wold’s decomposition has already been linked to scattering theory a long time ago, see for example [6,7]. In particular, it has been connected to the Lax–Phillips approach of scattering theory. However, we could not find explicit descriptions or pictures as provided in the present work.

5. Conclusions

The model introduced in this paper allows for the explicit computations of all objects in the related discrete time scattering theory. Various properties of these operators are clearly illustrated and discussed. Dynamical systems with explicit expressions are rather rare and should be used for introducing the theory at a pedagogical level. Finally, the expressions obtained illustrate a rather deep theorem of operator theory: Wold’s decomposition of isometries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R.; Methodology, S.R.; Software, R.R.F.; Validation, R.R.F. and S.R.; Formal analysis, S.R.; Investigation, R.R.F. and S.R.; Resources, R.R.F. and S.R.; Data curation, R.R.F. and S.R.; Writing—original draft, S.R.; Writing—review & editing, R.R.F. and S.R.; Visualization, R.R.F.; Supervision, S.R.; Project administration, S.R.; Funding acquisition, S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the referees for their critical reading of the manuscript and for their useful comments which led to a drastic improvement of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

In this section, we gather the technical results and proofs. We start with a proof of the existence of . Note that the argument can be mimicked for proving the existence of all other wave operators considered in this paper.

Proof.

Consider for some fixed and . Then, observe that the product can be computed explicitly and becomes independent of n for large enough. More precisely, for any one has

Similarly for any one has

Since the r.h.s. are independent of n, one infers that exist and are given by the above expressions. By linearity, and since is bounded with a norm independent of n, one infers that the wave operators exist. Their action on are the ones provided above. □

Proof of Lemma 1.

By a direct computation using the expressions obtained in (3) and (9), and in (4) and (10), one infers that for any and . By linearity, it then follows that , and the first statement is obtained by using the analytic formula (6). Similarly, by a direct computation one gets for any and . By linearity, one deduces that , and the analytic formula (7) leads to the second statement. Finally, one can also obtain that

from which we infer that

By linearity, the equality (11) follows from the analytic formula (7). □

Note that the above proof can be mimicked for obtaining the kernel and the cokernel of all wave operators or the scattering operator introduced in this paper.

Proof of Lemma 2.

It is known that if K is a compact operator and, if is any sequence converging weakly to 0 as , then converges strongly to 0 as , see for example [4] (Prop. 2.12). Thus, let us consider the sequence which is weakly converging to 0 as . Then by (12) and (13) one has

implying that the sequence does not converge strongly to 0 as . As a consequence, the operator is not a compact operator. □

References

- Asch, J.; Bourget, O.; Joye, A. Chirality induced interface currents in the Chalker-Coddington model. J. Spectr. Theory 2019, 9, 1405–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asch, J.; Bourget, O.; Joye, A. On stable quantum currents. J. Math. Phys. 2020, 61, 092104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisio, A.; Mosco, N.; Perinotti, P. Scattering and perturbation theory for discrete-time dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 126, 250503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amrein, W. Hilbert Space Methods in Quantum Mechanics; EPFL Press: Lausanne, Switzerland; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, K. C*-Algebras by Example; Fields Institute Monographs; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1996; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Masani, P. On the representation theorem of scattering. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 1968, 74, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sz.-Nagy, B. Isometric flows in Hilbert space. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1964, 60, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).