Abstract

Domain adaptation in image semantic segmentation has attracted more and more attention from computer vision and machine learning researchers. While the high cost of manual annotation is an unavoidable bottleneck in the semantic segmentation task, it is a high-quality solution to adopt pixel-level annotation from synthetic data, which provides additional support for deep learning training. Numerous studies have attempted to comprehensively investigate deep domain adaptation, but there is less focus on the sub-direction of the semantic segmentation task. This paper is devoted to this new topic in transfer learning. First, we describe the terminology and background concepts in this field. Next, the main datasets and evaluation metrics are introduced. Then, we classify the current research methods and introduce their contributions. Moreover, the quantitative results of the methods involved are compared, and the results are discussed. Finally, we suggest future research directions for this field. We believe researchers who are interested in this field will find this work to be an effective reference.

Keywords:

domain adaptation; semantic segmentation; transfer learning; unsupervised learning; urban scene understanding MSC:

68T05

1. Introduction

Computer vision tasks grounded in deep learning frequently hinge on a substantial volume of meticulously annotated data. However, the prohibitive expense and time-intensiveness associated with manual annotation pose significant hurdles for large-scale deep learning endeavors and impede the achievement of broad generalizability. Learning from synthetic data has emerged as a premium strategy, increasingly captivating the interest of the research community. Advanced computer graphics technology can efficiently generate synthetic images and their pixel-level annotations, providing support for training in deep learning, and these have been widely used in the field of computer vision [1], such as optical flow [2], object detection [3], semantic segmentation [4], multiview stereo [5], depth estimation [6], and target tracking [7]. In the realm of semantic segmentation, the advantages conferred by synthetic data are particularly pronounced. Tasks demanding pixel-level precision for dense prediction face the formidable and tedious challenge of manually delineating object boundaries with absolute accuracy. In the realm of semantic segmentation, the advantages conferred by synthetic data are particularly pronounced. This is exemplified by the laborious process of annotation: in the real dataset Cityscapes, it takes 90 min for each image to be labeled [8] and 60 min for each image in Camvid [9]. By contrast, the average annotation time of the synthetic dataset GTA5 is 7 s per image [10].

Inevitably, there are discrepancies between synthetic and real-world datasets that encompass variations in texture, lighting, and feature distribution. These disparities often hinder models trained exclusively on synthetic data from excelling when applied to real-world imagery. Researchers have attempted to tackle the problem using transfer learning [11] and have regarded the synthetic image as the source domain, the real image as the target domain, and the differences between them as the domain shift. Considering that the source domain contains sufficient pixel-level annotation, while the target domain does not, some researchers reduced the domain shift from discrepancy-based [12,13], adversarial-based [14,15], and reconstruction-based [16,17] perspectives. Collectively, these scholarly pursuits have yielded compelling evidence that deep domain adaptation has indeed made significant enhancements in the ability of models to generalize from synthetic to real-world environments.

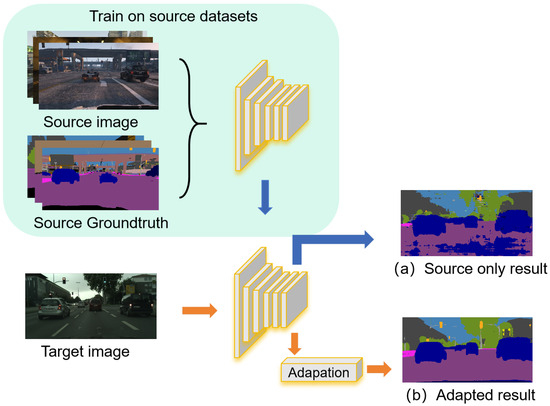

Figure 1 shows an example of semantic segmentation on unsupervised domain adaptation. In the training phase, labeled frames from video games are employed to train the segmentation network. In the testing phase, unlabeled frames from street view videos are used. In the absence of adaptation, as shown in Figure 1a on the right, obviously, the segmentation results are not satisfactory. However, after adaptation, the accuracy of the semantic category, semantic coherence, and segmentation edge has been significantly improved, as shown in Figure 1b.

Figure 1.

An example of semantic segmentation on unsupervised domain adaptation.

Currently, domain adaptation-based semantic segmentation faces several pivotal challenges. First, the issue of negative transfer poses a considerable hurdle. It refers to the phenomenon in which some features in the target domain have well-corresponded to their semantic counterparts but have been unexpectedly mapped to incorrect semantic categories after adaptation, decreasing the segmentation accuracy of the task. More recent attention has focused on how to automatically avoid negative transfer. Second is the fine segmentation challenge. We can see from segmentation results that the segmentation accuracy of large contour categories such as buildings and roads are usually very high, up to 98%. For small contour categories, such as pedestrians and traffic lights, the accuracy is significantly reduced, because the contour is too small to accurately locate the object boundaries. Even after adaptation, the segmentation accuracy of small contour categories is still not improved. Finally, there is the challenge of contextual information mining. In the process of transfer, some important contextual information including spatial and structural information can be used to improve the segmentation accuracy and avoid dividing a target into multiple parts or classifying different categories of targets into the same category.

Unsupervised domain adaptation enhances semantic segmentation by targeting three key areas. For the semantic category, it employs class-balanced losses and category-level adversarial alignment to correct classifier bias towards source-domain features, ensuring consistent recognition of object classes like “bus” or “tree” across domains. To improve semantic coherence, self-training with pseudo-labels and context-aware modeling enforces global prediction consistency, preventing unrealistic class adjacencies. For segmentation edges, multi-scale feature alignment and boundary-aware losses specifically refine object contours by aligning fine-grained features and penalizing blurry transitions, resulting in crisper and more precise boundaries in the target domain.

With the rise of multi-modal large models, a plethora of high-performance large-scale pre-training algorithms for general domains have emerged. When general models are used for specific tasks, domain adaptation issues also need to be addressed. DAFormer [18] first conducted benchmark tests on different network structures for UDA and revealed the potential of the Transformer in UDA semantic segmentation. Vision Transformers (ViTs) excel in unsupervised domain adaptation for semantic segmentation due to their self-attention mechanism, which provides a global receptive field from the first layer. This enables the modeling of long-range contextual dependencies, leading to shape-based representations that are more robust across domains than the texture-biased features of convolutional neural networks (CNNs). Additionally, ViTs’ weaker inductive biases force them to learn more fundamental visual concepts from data, creating features that are inherently more domain-invariant. This architectural superiority allows models like DAFormer to effectively bridge the domain gap by leveraging consistent semantic structures.

In the past few years, several systematic reviews of domain adaptation have been undertaken. In [11], transfer learning is divided into three categories: inductive transfer learning, transductive transfer learning, and unsupervised transfer learning. In [19], deep transfer learning is divided into four categories: instances-based deep transfer learning, mapping-based deep transfer learning, network-based deep transfer learning, and adversarial-based deep transfer learning [20]. According to the training loss, the deep domain adaptation method can be divided into three categories: classification loss, discrepancy loss, and adversarial loss. The subtitle of [21] summarizes the methods of semantic segmentation on domain adaptation, but it does not involve a related data introduction and comparative adaptation. Therefore, on the basis of reviewing the previous surveys, we make a more comprehensive investigation into the related research. Ref. [22] reviewed over 40 representative transfer learning methods from the perspectives of data and models and briefly introduced the applications of transfer learning. According to its classification, our work focuses on the subproblem of heterogeneous transfer learning, which is the knowledge transfer process carried out in different domains with different feature spaces. Ref. [23] organized semantic segmentation tasks from the perspective of open vocabulary, and inspired by this work, we conducted a review from the perspective of domain adaptation.

In this work, we have investigated semantic segmentation in the deep domain adaptation literature, and all the selected papers have been presented at professional conferences or published in journals. In detail, we introduce the main datasets and evaluation metrics. Meanwhile, we identify the difficulties, challenges, and future development directions. We aspire for this survey to provide researchers within the domain with an expanded understanding, offering them a holistic viewpoint that fosters deeper insights and inspires novel explorations in the realm of semantic segmentation under deep domain adaptation.

The remainder of this review is structured as follows. Section 2 provides the related notion and definition of this direction and arranges the main datasets and evaluation metrics. The approaches are analyzed and compared in Section 3. In Section 4, we suggest future research directions. Finally, the conclusion of this work is presented in Section 5.

2. Overview

2.1. Notations and Definitions

In this section, we introduce the symbols and definitions involved in this review. In order to maintain consistency across surveys, we use the symbols from [11,20,24] and extend them on this basis. Domain consists of feature space and marginal probability distribution , where , and the corresponding label is . Task consists of annotation space and target prediction function . From the perspective of probability, the target prediction function can also be regarded as the conditional probability distribution . We can learn from the labeled data , where , .

According to the definition in [24], the domain-adaptive semantic segmentation task belongs to the category of transductive TL. Both the source domain task and the target domain are semantic segmentation tasks. The source domain has sufficient labels, and the target domain has no or few labels. can learn from . At present, most of the work has been conducted under the unsupervised setting. Some novel work has started to explore the scenarios of data inaccessibility in the source domain, as well as few-shot in the target domain and multi-target domain. Our work investigates the relevant ideas and methods.

In the above settings, the training network on the source domain is supervised. Therefore, the cross-entropy loss commonly used in segmentation tasks is used in the source domain. On the one hand, limits the target task and does not deviate too far from the source solution. On the other hand, it guarantees the performance of the segmentation task. is commonly defined as follows:

represents the softmax predictions of the model, which represent the class probabilities, and is the number of classes.

2.2. Datasets

To better introduce the current methods of UDA for segmentation, we first introduce the mainstream datasets used in this field. First, the synthetic image in the source domain is similar to the real image in the target domain to some extent. In the existing scene, street view images are commonly used, most of which are converted from the synthetic street view to the real image captured from the driver’s perspective. Second, different domains share most of the categories. There are certain similarities in the category distribution of the image and the spatial structure.

The most commonly used synthetic-to-real datasets like GTA5 to Cityscapes and SYNTHIA to Cityscapes represent critical domain gaps in semantic segmentation. These include stark differences in visual style, with synthetic data exhibiting unrealistic textures and oversimplified object surfaces. The illumination models diverge significantly, creating unnatural lighting and shadow effects. Additionally, synthetic environments lack the complex noise, motion blur, and weather variations present in real-world imagery. Most importantly, they display limited object diversity and simplified geometric layouts, failing to capture the intricate chaos of authentic urban environments, which challenges model generalization.

Table 1 compares the main characteristics of the relevant datasets. The unit of resolution is the pixel, the unit of amount represents a single sheet, the instance level refers to whether the dataset contains instance-level annotation, the source refers to the acquisition method of images, and the depth refers to whether the dataset contains depth information. The bbbreviation Syn. means synthetic.

Table 1.

Comparison of mainstream datasets.

2.2.1. Cityscapes

The Cityscapes [8] (https://www.cityscapes-dataset.com, accessed on 5 November 2025) evaluation dataset was released by Mercedes Benz in 2015. It is one of the most authoritative and professional image semantic segmentation evaluation sets in the field of automatic driving. Focusing on the understanding of urban road environment in real scenes, Cityscapes includes 5000 fine annotation images and 2000 coarse annotation images under 30 categories. Figure 2 gives an example (https://www.cityscapes-dataset.com/examples, accessed on 5 November 2025) of these two types of annotation. The dataset was captured from more than 50 cities in Germany, France, and Switzerland. The scenes involved different seasons, weather, time, and traffic conditions. There are two tasks in the dataset: instance-level segmentation and pixel-level segmentation. Because of the high quality of the annotations, this dataset has become the default benchmark for semantic segmentation. Most of the articles mentioned in this work chose Cityscapes as the real scene dataset.

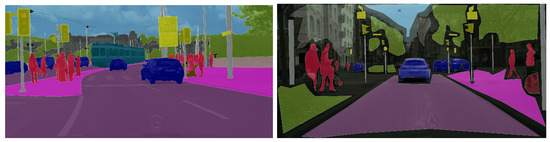

Figure 2.

The left side of the picture is fine annotation, and the right side is rough annotation.

2.2.2. GTA5

The GTA5 [10] (https://bitbucket.org/visinf/projects-2016-playing-for-data/src/master/, accessed on 5 November 2025) dataset obtains large-scale and accurate annotation data from famous commercial video game GTAV using advanced game engines. The game highly simulates the real world, from the texture of automobile materials, the spatial layout, and the movement of vehicles and pedestrians to the light; the details of the buildings are restored with great realism. GTA5 used computer graphics technology to extract 24,966 frames from GTAV. The resolution of each frame is 1914 × 1052 pixels, and the marking process takes 49 h to complete. These data cover 19 categories, which is a good virtual counterpart to the Cityscapes dataset. This dataset does not include instance-level annotation or depth information.

2.2.3. SYNTHIA

SYNTHIA [25] (http://synthia-dataset.net, accessed on 5 November 2025) is a virtual city image set generated by the Unity (https://unity.com, accessed on 5 November 2025) development tool, with a resolution of 1280 × 960. The image frame is obtained from multiple viewpoints and contains a related depth map. By simulating different times of the day and different seasons of the year, SYNTHIA also provides simulation images of sunny and cloudy skies, dusk, and four seasons. The image set contains 9400 high-resolution images and their pixel-level annotations. Annotations in SYNTHIA also include instance-level annotations. In addition, SYNTHIA contains multiple versions of image and video sets. Among them, the subset SYNTHIA-RAND-Cityscapes is compatible with the Cityscapes dataset [8], which contains 9400 synthetic road scene images.

The Unity engine enables SYNTHIA’s rich features through its real-time 3D-rendering capabilities, generating multiple perspectives and precise depth maps from virtual cameras navigating the simulated environment. Including diverse lighting conditions and seasons serves as explicit domain randomization, forcing models to learn illumination- and weather-invariant representations. This variability significantly improves model robustness by exposing the network to a wider spectrum of visual appearances, reducing overfitting to specific environmental conditions and enhancing generalization to real-world street scenes with unpredictable weather and temporal changes.

The SYNTHIA dataset extends beyond RAND-Cityscapes with sequences like SYNTHIA-Seasons (featuring varying weather conditions) and SYNTHIA-AL (simulating different times of day), which are vital for testing environmental robustness. It also includes video sequences enabling temporal consistency research for autonomous driving. The RAND-Cityscapes subset, with its precise semantic and instance-level alignment to Cityscapes’ classes, provides a controlled benchmark that eliminates annotation inconsistencies, allowing researchers to isolate and study pure domain shift without real-world data collection bottlenecks.

2.2.4. BDD100K

UC Berkeley released the BDD100K [26] (http://bdd-data.berkeley.edu, accessed on 5 November 2025) dataset, the largest and most diversified open driving video dataset so far, containing 100,000 videos. BAIR researchers sampled key frames on the video and obtained 100,000 pictures. The resolution of the pictures is 1280 × 720, and they provided comments for these key frames. BAIR performed full-frame instance segmentation for a data subset of 10,000 images. The annotation set is compatible with the training annotation in the Cityscapes dataset, making it convenient to study the domain adaptation between the two datasets. BDD100K, which was shot in the United States, covers different weather conditions, including sunny, cloudy, and rainy days, as well as different times of day and night. BAIR held a challenge competition based on its data in CVPR 2018 Autonomous Driving Workshop, including three tasks: road object detection, drivable area segmentation, and domain adaptation of semantic segmentation. Figure 3 gives an example of the annotations of the full-frame instance segmentation.

Figure 3.

Example annotations of full-frame instance segmentation from BDD100K dataset.

2.3. Evaluation Metrics

For the semantic segmentation on the UDA task, the evaluation metrics are divided into two aspects: segmentation metrics and adaptation metrics. From the perspective of image segmentation, the Intersection-over-Union () and Mean Intersection-over-Union () are used to evaluate the segmentation accuracy of the target domain. From the perspective of domain adaptation, the reduction in the adaptation method in domain shift is evaluated by comparing the differences between the adapted method and the corresponding source method. In Section 4, we use the following metrics to compare the methods mentioned in this work.

The MIoU gap is calculated by subtracting the target domain MIoU of the source-only model (trained solely on labeled source data) from the target domain MIoU of the adapted model (trained with UDA methods). A reduced gap signifies that the adaptation process has successfully bridged the domain shift, enabling the model to generalize its knowledge from the source domain to the target domain, rather than suffering from the performance degradation typically caused by distribution differences.

2.3.1. Segmentation Metrics

The mean intersection over union () [27] calculates the value of Intersection-over-Union () on each class, where the IoU is the standard of evaluation to detect the accuracy of the corresponding objects. Suppose in an image has classes (from 0 to K, including an empty class or background), where represents the number of pixels belonging to class i in the image and correctly predicted, that is, the number of true positive (), and () represents the number of pixels belonging to class i (j) but predicted as class j (i), that is, the number of false positive () and false negative () and the off-diagonal elements of the confusion matrix. The formula of is calculated as follows:

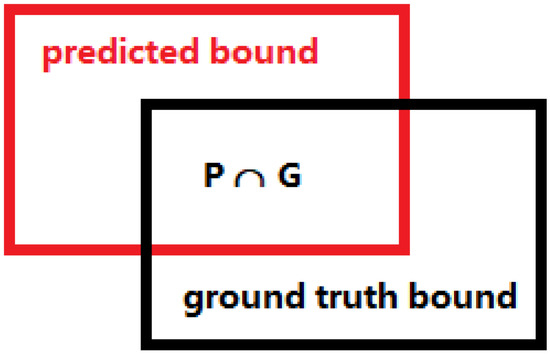

Visually, the represents the degree of coincidence between the predicted object box (predicted bound) and the real ground box (ground truth bound), that is, the ratio of the intersection and union of the two. If the value of is high, the higher the correlation is and the more accurate the prediction is; on the contrary, the lower the value is, the less accurate the prediction result is. The optimal value is 1; that is, the intersection and union are identical. It is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Calculation of MIoU.

The can be expressed as

2.3.2. Adaptation Metrics

The gain is the difference between the result of the segmentation task of the model with and without adaptations in the target domain. The model without adaptations is called the source model, which reflects the lower bound of the space that can be promoted by the corresponding method. The larger the gain value is, the more domain shifts are eliminated by the adapted model. The gain can be expressed as follows:

3. Methods

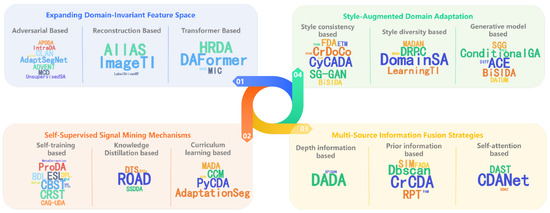

To systematically construct a research framework for adaptive semantic segmentation in urban scenes, we explore four core dimensions as shown in Figure 5: (1) Expanding Domain-Invariant Feature Space: how to construct more generalizable high-level semantic spaces through cross-domain representation learning; (2) Self-Supervised Signal Mining Mechanisms: how to leverage self-supervised cues to enhance feature discriminability; (3) Style-Augmented Domain Adaptation: how to reduce inter-domain distribution gaps via image style transfer and feature style disentanglement; (4) Multi-Source Information Fusion Strategies: how to integrate heterogeneous information to improve model robustness.

Figure 5.

Four dimensions to systematically construct a research framework for adaptive semantic segmentation in urban scenes.

3.1. Expanding Domain-Invariant Feature Space

In the task of universal domain adaptation, the first focus is on how to make the features between domains inseparable, explore the largest possible domain invariant space, and enable unsupervised target domains to obtain more sufficient guidance from source domain supervision information, thereby improving the performance of the target domain.

3.1.1. Adversarial-Based

Adversarial-based methods aim to learn domain-invariant feature representations by establishing a min–max game between a domain discriminator and a feature extractor. The target domain is directly regarded as the generated sample instead of the process of generating the sample. The generator acts as a feature extractor; learning the features of domain data constantly makes the discriminator unable to distinguish which domain the features come from. Adversarial training can be used in different stages of a network to improve the segmentation performance.

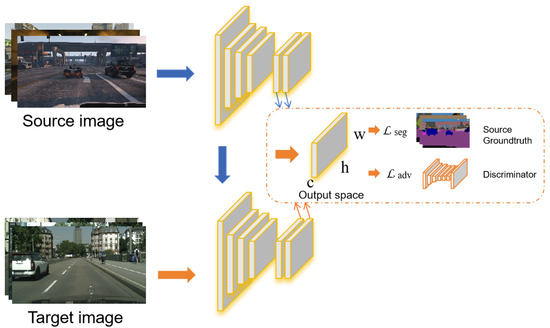

Early on, researchers used adversarial training to narrow down the inter-domain gap. In [28], the adversarial training is firstly applied to global domain alignment to obtain domain-invariant features in the global domain alignment together with MIL loss [29] in the category specific adaptation to align the local information in the category space. Subsequently, researchers attempted to use adversarial training from different perspectives to narrow down the inter-domain gap. In the space structure level, AdaptSegNet [4] (https://github.com/wasidennis/AdaptSegNet, accessed on 5 November 2025) observed that although the target domain and the source domain are different in appearance, their output is structured and shared spatially and locally, as shown in Figure 6. A multi-level adaptive learning scheme is proposed, which is used to discriminate between output (segmentation) space and low-level feature space, respectively. In the image space level, ref. [30] introduced a generator to transform the feature space into the image space; then, adversarial training was carried out on the generated image and the original image in the image space, and the domain invariance of the feature space was constrained by adversarial loss. In the activation distribution level, ref. [31] (https://github.com/RsEnts/DAM_release, accessed on 5 November 2025) extends the method of adversarial training to the activation distribution of the middle layer. Furthermore, ref. [32] extends the output space alignment to the patch level. In the weighted self-information space level, ADVENT [33] (https://github.com/valeoai/ADVENT, accessed on 5 November 2025) uses adversarial training to minimize the distribution distance between the source domain and target domain in weighted self-information space. IntraDA [34] (https://github.com/feipan664/IntraDA.git, accessed on 5 November 2025) extends adaptation to the gap inside the target domain based on ADVENT. A two-step self-supervised domain adaptation method is proposed. After inter-adaptation, the target domain is divided into a simple and a hard subdomain by entropy-based ranking, resulting in intra-domain differences. Furthermore, a self-training method is adopted to reduce the intra-domain gap. Ref. [35] introduces conservative loss based on adversarial training. The work of APODA [36] aims to mitigate domain shift through adaptive perturbation of the feature space from the perspective of an adversarial attack.

Figure 6.

Overview of method proposed in AdaptSegNet.

Furthermore, researchers deal with domain adaptation tasks from the perspective of a decision boundary between categories. In ADR [37] and MCD [38], in the prediction process, two different but effective classifiers are introduced with the dropout [39] method. SlicedWD [40] introduces the Sliced Wasserstein Discrepancy (SWD), utilizing the Wasserstein metric to minimize the cost of transporting marginal distributions between task-specific classifiers. The CLAN [41] (https://github.com/RoyalVane/CLAN, accessed on 5 November 2025) method extends two mutually exclusive classifiers to evaluate the alignment of features. When the difference between the two classifiers’ prediction results is large, it means that the features have not been well aligned, and the weight of the adversarial loss should be increased to better align the source domain and the target domain. The work of UnsupervisedSA [42] also uses two classifiers, but unlike CLAN, the author formulates in vivo memory regularization as the internal prediction discrepancy between the two classifiers.

Adversarial methods suffer from two fundamental limitations: First, excessive pursuit of domain invariance weakens feature discriminability, particularly causing semantic information loss in marginal categories leading to negative transfer. Second, global alignment ignores intra-domain class distribution imbalance, resulting in significantly worse cross-domain alignment quality for long-tail categories compared to frequent classes.

3.1.2. Reconstruction-Based

Reconstruction-based methods aim to maximize the exploration of the domain-invariant space through a combination of tailored reconstruction strategies, loss functions, and consistency constraints.

ImageTI [43] proposed the strategy of embedding space based on an encoder–decoder framework, which transforms between the source domain and the embedding space, the embedding space and the target domain, and constrains the consistency of the transformation through translation adversarial losses and cycle consistency losses. Meanwhile, it uses adversarial training to limit the domain independence of embedding space. The source domain and the target domain can share the annotation space and complete the domain adaptation. Discriminator distinguishes features from the X and Y fields in hidden space Z, , . These are binary tags from the X and Y fields. The loss function can be defined as the confidence of the discriminator, as follows:

where is the appropriate loss, which refers to the cross-entropy loss in the traditional GAN [44] and the mean square error of the least squares GAN [45]. The training goal of the counter is to maximize and minimize this error.

The encoder–decoder framework can not only obtain the hidden space through the overall image transformation, but also decouple the image into a domain-independent structure part and a domain-related texture part. Segmentation and adversarial training are only conducted in the domain-independent structure part to make the domain adaptive. In AllAS [46], the encoder is divided into two parts: a common encoder and a private encoder, with the common encoder coding the domain-independent structure and the private encoder coding the domain-related texture part.

LabelDrivenRF [47] combines inter domain translation with label-driven reconstruction. The author first makes target-to-source translation to obtain source-like image, and then perform segmentation on these translated images. The segmentation accuracy in the target domain is improved by reconstructing both source and target images from their predicted labels.

Reconstruction-based domain adaptation methods exhibit two limitations. First, the strong assumption of feature disentanglement often fails in practice, as encoders cannot fully separate domain-invariant and domain-specific features. Second, pixel-level reconstruction loss forces the model to focus on low-level texture details, which conflicts with the high-level semantic understanding required for segmentation.

3.1.3. Transformer-Based

Transformer-based methods aim to utilize the superior representation learning capabilities of large-scale models to discover and characterize domain-invariant spaces.

DAFormer [18] is the opening work of unsupervised domain adaptation for semantic segmentation using Transformer, as shown in Figure 7. Furthermore, HRDA [48] can adapt to small objects and preserve fine segmentation details, while the MIC [49] module randomly masks image patches and enforces consistency between the corresponding masked target images, additionally generating pseudo-labels through an exponential moving average teacher model based on the complete images. DGSS [50] uses a set of collaborative foundational models for domain-wide semantic segmentation and proposes a framework called CLOUDS that integrates various FMs.

Figure 7.

Overview of method proposed in DAFormer.

Transformer-based domain adaptation methods exhibit certain limitations. For instance, the self-attention mechanism shows insufficient perception of local details; while it effectively captures the global context, it tends to overlook edge features critical for segmentation tasks, such as object boundaries and small target structures. Given the high computational cost and resource constraints associated with large pre-trained models, the most promising methods for efficient unsupervised domain adaptation in urban scene segmentation focus on strategic resource allocation through parameter-efficient fine-tuning techniques like low-rank adaptation (LoRA) or visual prompt tuning, which update only minimal parameters while preserving pre-trained knowledge.

3.2. Self-Supervised Signal Mining Mechanisms

In domain-adaptive semantic segmentation tasks, since the target domain does not have labeled information, auxiliary tasks (proxy tasks) can be designed through self-supervised learning to mine the representation characteristics of the data themselves as supervised information, in order to improve the feature extraction ability of the model. Therefore, how to design auxiliary tasks is the key to domain-adaptive semantic segmentation tasks. We introduce four perspectives: knowledge distillation, course learning, self training, and active learning.

3.2.1. Self-Training-Based

Self-training-based methods aim to improve model performance by using predictions from a previous training state as pseudo-labels for unlabeled data. These labels are then used to supervise the training of the current model, effectively bootstrapping its learning from its own most confident outputs.

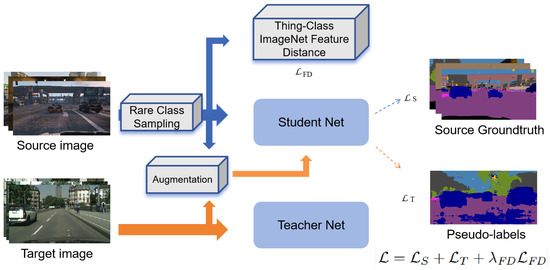

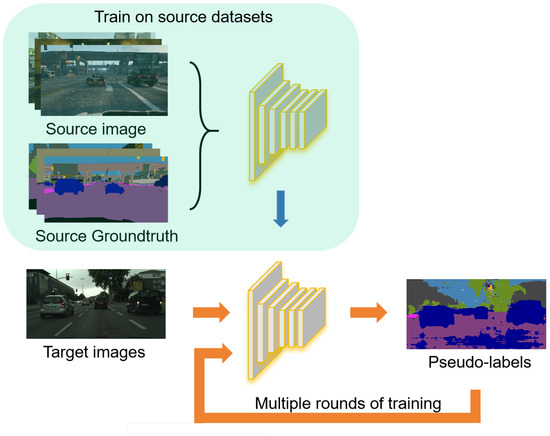

CBST [51] (https://github.com/yzou2/cbst, accessed on 5 November 2025) proposed a Class-Balanced Self-Training framework based on self-training, as shown in Figure 8. Inspired by self-paced learning, using the learning strategy of easy-to-hard, a pseudo-label with high confidence was selected to participate in the next round of training, and the threshold is selected by the self-training of multiple iterations. CRST [52] (https://github.com/yzou2/CRST, accessed on 5 November 2025) proposed two methods of confidence regularization to reduce the misleading effect caused by incorrect or ambiguous supervision in CBST. Zheng et al. [53] (https://github.com/layumi/Seg-Uncertainty, accessed on 5 November 2025) model the uncertainty via the prediction variance, and the uncertainty is used to rectify the pseudo-label.

Figure 8.

Overview of method proposed in CBST.

ESL [54] proposed a novel viewpoint in the selection of pseudo-labels, which uses entropy as a confidence indicator to produce more accurate pseudo-labels. The performance of the segmentation network is improved by improving the quality of the label map.

Some methods are promoted at the framework level. BDL [55] (https://github.com/liyunsheng13/BDL, accessed on 5 November 2025) proposes a bidirectional learning framework method, which consists of two independent phases. In the translation to segmentation phase, the source domain and target domain are trained at the same time, while the pixel blocks with high confidence are retained, and the pixel blocks with low confidence are discarded. In the segmentation to translation phase, conceptual loss is introduced to constrain semantic consistency. DPL [56] (https://github.com/royee182/DPL, accessed on 5 November 2025) proposed a novel dual path learning framework to alleviate visual inconsistency. It contains two complementary and interactive single-domain adaptation pipelines aligned in the source and target domains, respectively. SAC [57] (https://github.com/visinf/da-sac, accessed on 5 November 2025) proposed an end-to-end model using co-evolving pseudo-labels.

Some methods are promoted at the category level. CAG-UDA [58] (https://github.com/RogerZhangzz, accessed on 5 November 2025) proposed an anchor-guided unsupervised domain adaptation model. The centroid of category-wise features in the source domain is used as anchors to identify the active features in the target domain. Then, pseudo-labels are assigned to these activity features according to the category of the closest anchor. LearningFS [59] proposed an approach of exploiting the scale-invariance property of the model to generate pseudo-labels. Class-specific dynamic entropy thresholding is introduced so that pixels belonging to classes at different adaptation stages could be judged differently when included in the loss function. ProDA [60] (https://github.com/microsoft/ProDA, accessed on 5 November 2025) rectified the pseudo-labels by estimating the class-wise likelihoods according to their relative feature distances to all class prototypes. The author proposes to align soft prototypical assignments for different views of the same target, which produces a more compact target feature space. Ref. [61] proposed a coarse-to-fine pipeline that seamlessly combines coarse image-level alignment with finer category-level feature distribution regularization.

MetaCorrection [62] (https://github.com/cyang-cityu/MetaCorrection, accessed on 5 November 2025) presents a DMLC strategy that formulates the misclassification probability of inter-classes to model noise distribution in the target domain and devises a domain-aware meta-learning algorithm to estimate the NTM for loss correction in a data-driven manner. The framework provides matched and compatible supervision signals for different layers to boost the adaptation performance of model.

SAC [57] proposed a strategy for self-supervised data augmentation consistency, which combines standard data augmentation techniques and semantic consistency constraints in a lightweight self-supervised framework to reduce the complexity of the self-supervised model. DiGA [63] proposed a threshold free dynamic pseudo-label selection mechanism to solve the problem of selecting appropriate classification thresholds, enabling the model to better adapt to the target domain. RPLR [64] proposes a reliable pseudo-label retraining strategy that utilizes the prediction consistency of a network trained on mult-view source images to select clean pseudo-labels for retraining on unlabeled target images.

Refign [65] applies self-training methods to DAFormer. Furthermore, ref. [66] applied self-training to domain-adaptive semantic segmentation tasks without accessing source data. Ref. [67] proposed using implicit neural representations to estimate the correction values for predicting pseudo-labels.

Self-training-based domain adaptation methods face two limitations. First, initial errors in pseudo-labels become amplified through iterative reinforcement, creating a vicious cycle of error confirmation that particularly impacts long-tail categories and boundary regions. Second, the confidence threshold mechanism presents an inherent dilemma: high thresholds yield sparse supervisory signals, while low thresholds introduce substantial label noise.

3.2.2. Knowledge Distillation-Based

Knowledge distillation- [68] based methods aim to compress model knowledge by training a lightweight student model to mimic the output distribution of a powerful teacher model. The core idea is to transfer generalization ability; by learning from the teacher’s “soft targets”, which contain richer information than hard labels, the student model achieves better performance than training on the original data alone, as formalized by a modified Softmax objective function:

Based on the standard SoftMax function, the parameter of temperature T is introduced. In the standard SoftMax, T is 1, that is, a hard target. The amount of information contained in it is very low. The amount of information contained in a soft target is large, and it contains information on different kinds of relationships.

ROAD [69] designs a new loss function in target-guided distillation and spatial aware adaptation. The real image is input into the segmentation model and the pre-training model, respectively, and distillation loss is used to encourage the segmentation model to distill knowledge from the pre-training model. SSDDA [70] contains a two-step semi-supervised dual-domain adaptation approach and introduces a new perspective of intra-domain discrepancy within the target domain. Intra-domain adaptation is achieved using a separate student–teacher network.

DTS [71] applies self-training methods to DAFormer and proposes a new dual teacher student framework, equipped with a bidirectional learning strategy. RTEa [72] proposed a pseudo-relation learning framework called relation teacher, which can effectively utilize pixel relations to use unreliable pixels and learn generalized representations.

Knowledge distillation-based domain adaptation methods face several key limitations. First, their effectiveness heavily relies on the teacher model’s quality—if the teacher contains domain-specific biases, these errors can be amplified when transferred to the student model. Second, tuning the temperature parameter T requires extensive experimentation, and a fixed value often fails to adapt to the varying uncertainty distributions across different samples.

3.2.3. Curriculum Learning-Based

Curriculum learning- [73] based methods aim to accelerate training and converge to a better local optimum by imitating human learning. This is achieved through a curriculum that progressively shifts the training focus from easy to hard samples, initially weighting them differently before final unified training on the entire dataset.

AdaptationSeg [74] (https://github.com/YangZhang4065/AdaptationSeg, accessed on 5 November 2025) uses the global alignment of the image and the alignment of the super-pixel label distribution to perform the domain adaptation task. Inspired by curriculum learning, the author chooses to infer the target properties of the target image and the landmark superpixels distribution as the simple task of the deny prediction task. The results of simple tasks can effectively assist the prediction of semantic segmentation tasks.

PyCDA [75] (https://github.com/lianqing11/pycda, accessed on 5 November 2025) introduces the method of self-motivated pyramid curriculum domain adaptation, where a pyramid curriculum contains various properties of the target domain. These properties are mainly about the desired label distributions on target domain images, image regions, and pixels. By enforcing piecewise, the neural network observes these properties, and the generalization capability of the network to the target domain can be improved. CCM [76] (https://github.com/Solacex/CCM, accessed on 5 November 2025) actively selects positive source information for training to avoid negative transfer. The author uses Content-Consistent Matching (CCM) to select positive source samples and their positive pixels, which includes Semantic Layout Matching and Pixel-wise Similarity Matching. A self-training paradigm is adopted in the implementation of CCM; that is, the representations are updated through self-training, and the source-matching results are updated through CCM.

MADA [77] (https://github.com/munanning/MADA, accessed on 5 November 2025) introduced a multi-anchor-based active learning strategy. By adopting multiple anchors instead of a single centroid, the source domain can be better characterized as a multi-modal distribution; thus, more representative and complimentary samples are selected from the target domain. RIPU [78] proposed a simple region-based active learning approach for semantic segmentation under a domain shift, aiming to automatically query a small partition of image regions to be labeled while maximizing the segmentation performance.

Curriculum learning-based domain adaptation methods face two limitations. First, the criteria for defining “easy vs. hard samples” lack objective quantification, as current approaches predominantly rely on prediction confidence, where confidence scores often deviate from actual errors. Second, these methods exhibit high sensitivity to data distribution, making it difficult to balance learning progression between common and rare categories within complex long-tailed urban scenes.

3.3. Style-Augmented Domain Adaptation

Compared with general domain-adaptive tasks, semantic segmentation tasks focus more on extracting semantic features and predicting at the pixel level. Therefore, researchers have attempted to study this from the perspective of style enhancement. The method of adversarial training can also be applied to domain-adaptive semantic segmentation from the perspective of style consistency. Huang and [79,80] generate labeled images with the target domain style to expand the training data. With the rise in generative models, researchers have further introduced diffusion models. In DASS tasks, style enhancement mainly includes the following perspectives: (1) style consistency-based, (2) style diversity-based, and (3) generative model-based.

3.3.1. Style Consistency-Based

Style consistency-based methods aim to narrow the domain gap by explicitly aligning the style characteristics between the source and target domains, while often incorporating semantic consistency constraints to facilitate the discovery of a larger domain-invariant space.

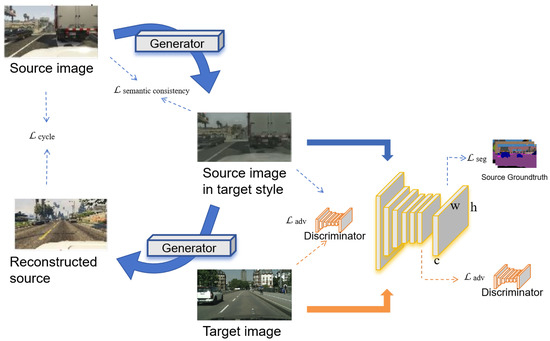

Hoffman et al. proposed Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Domain Adaptation (CyCADA) [81] (https://github.com/jhoffman/cycada_release, accessed on 5 November 2025), as shown in Figure 9. Inspired by Cycle-GANs, CyCADA transforms the source domain image into the target style and then transforms the target domain image into the source style. Under the condition of semantic consistency, the transformed image can share the label with the source domain image, that is to say, label transfer. SG-GAN [82] (https://github.com/Peilun-Li/SG-GAN, accessed on 5 November 2025) introduced semantic-aware Grad-GAN. A gradient-sensitive objective is introduced into the generator to render distinct colors/textures for each semantic region to maintain the semantic boundary. Distinct discriminate parameters are learned in the semantic-aware discriminator, so as to examine regions with respect to each semantic label.

Figure 9.

Overview of method proposed in CyCADA.

CrDoCo’s method [83] (https://yunchunchen.github.io/CrDoCo/, accessed on 5 November 2025) transfers the source domain image into the target domain style image and the target domain image into the source domain style image. Meanwhile, semantic consistency after constraint transformation is achieved by image level and feature level adversarial training. The method in FDA [84] does not require any training to perform domain alignment, only simple Fourier transform and its inverse. BiSIDA [85] also adopts a bidirectional style-induced method. The innovation is to use the style-induced image generator as an enhancement method and transfer each target domain image together with some randomly sampled source domain images. ETM [86] (https://github.com/joonh-kim/ETM, accessed on 5 November 2025) introduced an Expanding Target-specific Memory framework for continual UDA. It contains Target-specific Memory (TM) for each target domain to alleviate catastrophic forgetting.

FCAN [87] introduced a method of domain adaptation that separates the appearance level and the representation level, that is, style and semantic information. Only the style part is transferred, while the semantic part acquires the unchanging part of the domain through adversarial training. Similar to FCAN, DCAN [88] divides the domain shift into low and high levels. While preserving spatial structures and semantic information, the features of the composite image are further normalized specifically to the sampled target image, and finally, the segmentation results are generated. CIR [89] introduces the idea of Content Invariant Representation (CIR), which uses an intermediate domain to share invariant content with the source and similar distribution to target. Combined with the Ancillary Classifier Module (ACM), it adaptively assigns different weights to pixels, to reduce the local domain gap. Ref. [90] designs the structure of one content encoder and two style encoders with zero-style loss and realizes more accurate feature-level domain adaptation by independently separating the content and style of the image.

Style consistency-based domain adaptation methods face two limitations. First, excessive focus on style transfer may compromise the structural integrity, while strict semantic maintenance can restrict the degree of style transformation. Second, these methods often define style features narrowly, focusing mainly on low-level statistics like color and texture, which inadequately captures complex domain variations such as lighting conditions and weather changes.

3.3.2. Style Diversity-Based

Style diversity-based methods aim to expand the model’s representational capacity by exposing it to a broad spectrum of stylistic variations beyond the immediate source and target domains, thereby forcing it to learn more domain-agnostic features.

The method of DomainSA [3] is divided into two steps, domain stylization (DS) and semantic segmentation learning (SSL), which are carried out alternately. The domain styling (DS) part uses the method in fastphotostyle [91] to randomly select 10 images from the real image and the virtual image, respectively, convert the virtual image to the real image style, and carry out alternate training with the semantic segmentation learning (SSL) step.

DRPC [92] (introduces the method of domain randomization. By using CYCLE-GAN, the source domain image can be transformed into multiple auxiliary domains. The style of the auxiliary domain is different from the source domain, but the semantic information can be retained to the maximum extent. The extended data are used to train the segmentation model. LearningTI [93] (https://github.com/MyeongJin-Kim/Learning-Texture-Invariant-Representation, accessed on 5 November 2025) further expands the diversity of domains on the basis of DRPC [92]. The author considers that texture is the fundamental difference between the two domains. They propose to adapt to the texture of the target domain and use the style transfer algorithm Style-swap [94] and Cycle-GAN [80] to create texture diversity in synthetic images.

MADAN [95] (https://github.com/Luodian/MADAN, accessed on 5 November 2025) proposes a pixel-level dynamic adversarial image generation module, which is similar to the idea of CyCADA. Sub-domain Aggregation Discriminator and Cross-domain Cycle Discriminator are designed to align multi-source domains. Unlike MADAN, MSDA [96] aims to translate source domain images to the target style by aligning different distributions to the target domain in LAB color space. Then, domain adaptation is combined with collaborative learning between source domains.

Style diversity-based domain adaptation methods face two limitations. First, the generated multi-style samples often lack guaranteed semantic consistency, as geometric distortions and texture artifacts during style transfer may corrupt structural information in the original images. Second, these methods heavily depend on the coverage of the style library. If the stylistic distribution of auxiliary domains significantly diverges from the actual target domain, it may cause the model to learn irrelevant domain-invariant features, resulting in adaptation bias in real-world scenarios.

3.3.3. Generative Model-Based

Generative model-based methods aim to address the challenges of domain adaptation in semantic segmentation by leveraging the power of generation to produce task-specific images that bridge the domain gap. Generative style transfer methods fundamentally advance beyond early GANs by leveraging diffusion models to achieve finer and more controllable stylization. Unlike GANs’ adversarial single-style mapping, diffusion models employ progressive denoising to generate higher-fidelity and diversified stylized outputs.

Inspired by [79], ACE [97] proposes a style transfer method using an encoder and generator to generate a source domain image with the target domain style and constrain its semantic consistency and then generate a target domain image with a label. Inspired by lifelong learning [98], using source domain images and synthetic images to train the segmentation network at the same time, the segmenter uses the knowledge accumulated in the past to learn and adapt to new tasks. ConditionalGA [99] uses noise and low-level fine-grained detailed features as the input of a conditional generator, and feature maps of the source image are transformed, to make it like sampling from the target domain, while maintaining its semantic spatial layouts. BiSIDA [85] also adopts a bidirectional style-induced method. The innovation is to use the style-induced image generator as an enhancement method and transfer each target domain image together with some randomly sampled source domain images. In the supervised stage and unsupervised stage, the direction of high-dimensional perturbation is opposite.

With the rise in large models, researchers have begun to seek new style transfer methods from the perspective of diffusion models to achieve better domain adaptation. Researchers describe cross-domain image translation as a denoising diffusion process. SGG [100] utilizes a new semantic gradient guidance method to constrain the translation process, limiting it to pixel-level source labels. DATUM [101] introduced a text-to-image diffusion model, where the text interface allows us to guide image generation towards the desired semantic concepts while maintaining the spatial context of the original training images. DIFF [102] uses diffusion feature fusion as the backbone for extracting and integrating effective semantic representations through diffusion processes. PFA [103] uses a progressive feature alignment method to align the intermediate domain image generated by the generative model with the source domain image.

Generative model-based domain adaptation methods face two limitations. First, high-quality image generation typically requires complex models that significantly increase the computational costs, while lightweight models may lead to semantic information loss or boundary distortion. Second, excessive emphasis on style variation can disrupt structural consistency, whereas overly conservative generation strategies fail to adequately cover the target domain’s true distribution, limiting the model’s generalization capability.

3.4. Multi-Source Information Fusion Strategies

In addition to the above research ideas, researchers have further explored the introduction of diverse information into the unsupervised source domain to explore richer guidance information for the target domain. We discuss this in three categories: depth information, prior information, and self-attention.

3.4.1. Depth Information-Based

Depth information-based methods aim to leverage depth cues to enhance domain adaptation for semantic segmentation. These approaches typically employ an auxiliary network that predicts the depth from shared inputs to assist adversarial training. By integrating depth-aware modules that encode and fuse depth predictions with backbone features, they effectively narrow the domain gap between the source and target domains, improving segmentation performance in unsupervised adaptation scenarios.

SPIGAN [104] makes full use of the depth information in the SYNTHIA dataset as privileged information and introduces the privileged network P to assist the adversary training network in the task network T segmentation task training. The input into the privilege information training network and task network is the same; the difference is that the output of the task network is semantic segmentation, and the output of the privilege information training network is the prediction of the depth information. Inspired by SPIGAN [104], the author of ADVENT [33] further studies the role of depth information in task segmentation. DADA [105] (https://github.com/valeoai/DADA, accessed on 5 November 2025) introduces a new depth-aware segmentation pipeline. A new module is added to the existing segmented network structure. First, the backbone CNN features are encoded, and the encoded output is predicted by depth mapping through the average pooling layer. At the same time, the output decoding after encoding is fused with the backbone features. Depth information and weighted self-information are integrated, and the gap between the source domain and the target domain is narrowed through adversarial training.

Methods based on depth information face two limitations. First, their effectiveness heavily depends on the accuracy of the depth estimation: the target domain depth data can be unreliable or exhibit domain discrepancies. Second, the fusion mechanism between depth and semantic features is often simplistic, struggling to establish effective semantic correspondence between the two modalities.

3.4.2. Prior Information-Based

Prior information-based methods aim to leverage intrinsic properties like contextual relations, category semantics, and spatial logic to enhance domain adaptation. These approaches utilize co-occurrence relationships, category-level grouping strategies, and fine-grained feature alignment to improve segmentation consistency. By incorporating structural priors through pseudo-label transfer and specialized discriminators, they effectively narrow the domain gap while maintaining semantic coherence across domains.

CrCDA [106] focuses on the co-occurrence relation in global-level alignment and proposes a local context-consistent domain adaptation method. Through Dbscan [107], the pseudo-annotation information of the local context is established in the source domain ground truth and is transferred to the target domain to improve the segmentation quality. RPT [108] represents Regularizer of Prediction Transfer (RPT), which can find additional regularization methods based on semantic segmentation intrinsic and generic properties in the target domain. The model transformation is regularized by patch-based consistency, cluster-based consistency, and spatial logic in an unsupervised way. SIM [109] began to explore internal differences at the category level. This paper proposes a framework based on stuff and instance matching (SIM), which improves the consistency of the semantic level by different strategies for stuff regions and for things. The work of [110] is similar to SIM. The difference is that the author divides the category into multiple groups. The grouping network and segmentation network can be trained in a joint and boosting manner. FADA [82] further extends intrinsic properties to the category level. Class information is directly incorporated into the discriminator and encourages it to align features at a fine-grained level, in order to distinguish the importance of intra-domain category knowledge. PAM [111] focuses on category asymmetry in category level feature alignment. This work aims to distinguish the importance of outlier categories and non-outlier categories from the perspective of partial adaptation.

Methods based on prior information face two main limitations. First, the semantic relationships or spatial logic they rely on are often derived from source domain statistics, which may become ineffective or even introduce biases when target domain distributions differ significantly. Second, complex prior modeling substantially increases the computational complexity, and the optimization objectives across multiple modules are difficult to balance, easily leading to training instability.

3.4.3. Self-Attention-Based

Self-attention-based methods aim to enhance domain adaptation by capturing cross-domain context dependencies through attention mechanisms. These approaches utilize spatial and channel attention modules to model transferable features across domains, while some methods employ discriminator-guided attention to identify and focus on poorly-aligned features. By sharing attention maps between domains or leveraging confidence scores to refine feature alignment, these methods effectively improve the adaptation of contextual information in semantic segmentation tasks.

CDANet [112] proposes the transfer of context information at the image level. The author proposes a cross-attention mechanism based on self-attention to capture context dependencies between domains and to adapt to the transferable context. Inspired by DANet [113], two cross-domain attention modules are designed to capture the context dependencies of spatial and channel views, respectively. DAST [114] (introduces a new method with discriminator attention. It is used to explicitly distinguish between well-aligned and poorly-aligned features and guide the model to pay attention to the latter. Unlike CDANet [112], DAST implements the attention map from the discriminator confidence score of intermediate features.

In the DAFormer stage, CDAC [115] introduced cross-domain attention consistency, using cross-domain attention layers to share attention maps between the source and target domains for adaptive execution.

Self-attention-based domain adaptation methods face two limitations. First, the high computational complexity of self-attention modules restricts their application in resource-constrained scenarios. Second, attention mechanisms are susceptible to domain discrepancies and may focus on irrelevant contextual information in the target domain, potentially amplifying cross-domain biases. Additionally, while attention maps offer strong interpretability, directly constraining them may undermine the model’s feature learning capacity.

3.5. Comparison

To clearly demonstrate the quantitative progression of the field, this study selects widely adopted standard benchmarks (GTA5 to Cityscapes and SYNTHIA to Cityscapes) and employs representative backbone networks from the ResNet and DeepLab series for systematic comparative analysis.

In the process of data adaptation from the SYNTHIA dataset to the Cityscapes dataset, some methods use 13 classes of the SYNTHIA dataset, some methods use 16 classes of the SYNTHIA–Cityscapes dataset, and we use ∗ to mark the data under the 13 classes condition.

The ResNet [116] and DeepLab [117] series represent mainstream architectures in contemporary semantic segmentation research. This survey systematically selects and compares algorithms built upon these backbone networks for comprehensive analysis. The methods in our survey use ResNet-38, ResNet-50, and ResNet-101 as the base net. The results of the quantitative comparison are shown in Table 2 and Table 3. For DeepLab series, the methods in this work use Deeplab V2 [118] and Deeplab V3 [119] as the base net. The results of the quantitative comparison are shown in Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 2.

Comparison of ResNet series from GTA5 to Cityscapes.

Table 3.

Comparison of ResNet series base net from SYNTHIA to Cityscapes.Some methods use 16 classes of the SYNTHIA–Cityscapes dataset, and we use * to mark the data under the 13 classes condition.

Table 4.

Comparison of Deeplab series from GTA5 to Cityscapes.Some methods use 16 classes of the SYNTHIA–Cityscapes dataset, and we use * to mark the data under the 13 classes condition.

Table 5.

Comparison of Deeplab series base net from SYNTHIA to Cityscapes.

In the GTA5 to Cityscapes task, Table 2 and Table 4 show that domain-adaptive semantic segmentation performance has a continuous improvement trend. Methods based on the ResNet series progressed from a baseline of 36.6% through adversarial learning (AdaptSegNet reached 42.4%) and self-training (BDL reached 48.5%), to prototype alignment (ProDA reached 57.5%). The DeepLab series demonstrated even higher potential, advancing from a baseline of 40.0% via multi-source domain adaptation (MADAN reached 55.7%) and multi-anchor strategies (MADA reached 64.9%) to achieve remarkable breakthroughs. The overall evolution trajectory reveals that DeepLab V3, with its superior contextual modeling capabilities, eventually surpassed ResNet in later stages, while innovations in training strategies became the primary driver of performance gains.

In the SYNTHIA to Cityscapes task, Table 3 and Table 5 show that domain adaptation methods demonstrate a steady performance improvement trajectory. The ResNet series started from a baseline of 33.5%, progressing through adversarial training (DCAN reached 36.5%) and self-supervised optimization (IntraDA reached 41.7%) to advanced fusion strategies (SAC reached 52.6%). The DeepLab series shows more prominent performance, advancing from a baseline of 34.9% via curriculum learning (ETM reached 38.7%), through pseudo-label optimization (RectifyingPL reached 47.9%) to prototype denoising (ProDA reached 55.5%), achieving remarkable breakthroughs. Overall, methods evaluated under the 16-class metric system average approximately 7–9 percentage points lower than those under the 13-class system; however, the best methods exhibit consistent performance growth under both evaluation standards. The refinement of pseudo-label quality and feature alignment strategies emerge as key drivers of this progress.

4. Future Research Directions

The above work summarizes the latest research in domain adaptation for segmentation, which marks the state of the art in this field. Based on this, we suggest future research directions, which will be an interesting list for researchers to pursue.

4.1. Open Vocabulary Scenario

Open-vocabulary semantic segmentation aims to segment images into semantic regions based on text descriptions, including categories unseen during training. While numerous excellent works like ZeroSeg [121], OVSeg [122], SAN [123], ProxyCLIP [124], and Mask-Adapter [125] have leveraged pre-trained Vision-Language Models (VLMs) like CLIP and demonstrated effectiveness on general datasets, their application in complex urban scenes faces distinct challenges. General models like CLIP often struggle with the fine-grained class distinctions crucial in urban environments—for instance, differentiating between visually similar vehicle types such as “sedan,” “SUV,” and “truck” or distinguishing specific road structures like “roundabouts” versus “intersections.” The reliance on broad semantic concepts during pre-training may not capture these nuanced domain-specific visual features, limiting model precision in practical applications like autonomous driving. Therefore, future work must focus on enhancing the fine-grained recognition capabilities of VLMs within the urban context.

4.2. Multi-Modal Scenario

Under multi-modal settings, semantic segmentation adapted to urban scenes can significantly improve generalization by leveraging complementary information from diverse sensors. Beyond foundational visual-language models like FLAVA [126], urban environments offer rich complex data sources including radar, LiDAR, and depth information. Effective fusion strategies are key: for instance, early fusion can combine raw LiDAR point clouds with RGB pixels through voxelization or projection, while intermediate fusion could align radar object detections with image features via cross-attention mechanisms. Decision-level fusion offers another avenue, where segmentation logits from RGB and LiDAR streams are merged using confidence-weighted averaging. Exploring these fusion methods specifically for cross-domain alignment—such as using LiDAR’s structural consistency to guide RGB feature adaptation—represents a critical research direction.

Furthermore, multi-modal foundation models like CLIP can revolutionize urban scene UDA by generating more accurate pseudo-labels through cross-modal reasoning. Their text-guided visual understanding enables precise class boundary detection in ambiguous scenarios—distinguishing “construction barrier” from “curb” using semantic context. By incorporating textual descriptions of urban elements (“wet road,” “night scene”), these models provide richer contextual cues that help bridge domain gaps.

4.3. Prompt-Based Large Model Scenario

Pre-trained large Vision-Language Models (VLMs) have achieved remarkable success across various downstream tasks. Ref. [127] has shown that unsupervised prompt-based tuning of VLMs can effectively reduce distribution shifts between the source and target domains in UDA tasks. For urban scene adaptation, designing effective prompts is crucial. These might include contextual cues like “a city street scene at night with wet roads,” domain-invariant descriptions such as “an urban driving view with vehicles and pedestrians,” or task-specific instructions like “segment all drivable areas and dynamic objects.” However, research on applying prompt-based VLMs to domain-adaptive semantic segmentation in urban environments remains nascent and warrants substantial further investigation.

4.4. Source-Free Domain Adaptation Scenario

Source-free domain adaptation has garnered widespread attention due to its ability to address issues related to data privacy, transmission, and storage. In this setting, model adaptation can only utilize a pre-trained model from the source domain without accessing any original source data. SHOT [128] learns target domain features solely using the features extracted by the source model through information maximization and pseudo-label self-training. SFDA [129] proposed a teacher–student-like framework that gradually adapts to the target domain by generating high-quality pseudo-labels. These methods provide feasible technical pathways for real-world deployment in data-constrained scenarios.

4.5. Multi-Target Domain Adaptation Scenario

Multi-target domain adaptation aims to enable a model to simultaneously adapt to multiple target domains with different data distributions (e.g., adapting to multiple cities with different climates or urban styles). This aligns closely with the real-world need to deploy models across diverse environments at once. MTDA [130] handles multiple target domains simultaneously through feature alignment and the design of domain-specific classifiers.

4.6. Continual/Lifelong Adaptation Scenario

Continual/Lifelong adaptation requires models to learn continuously from non-stationary data streams, adapting to environmental changes (such as seasonal transitions from summer to winter) without catastrophically forgetting previously acquired knowledge. This is considered a core capability for achieving long-term autonomous systems. Continual DA [131] preserves adaptation capability for previous domains through knowledge distillation and feature replay. This direction is crucial for realizing truly intelligent and evolving perception systems.

5. Conclusions

As transfer learning continues to evolve, its research scope and applications have become increasingly diverse. Distinguishing itself from broader surveys, our work zeroes in on this nascent frontier of transfer learning, encapsulating the discipline’s cutting-edge and most recent advancements. By doing so, we equip readers with the foundational knowledge vital for navigating this emergent discipline. We cover methods and datasets in the contemporary literature and provide a comprehensive survey of mainstream methods and datasets. This work describes the datasets in detail, explains their usage and characteristics, and provides an effective way to obtain them, so that researchers can choose the most suitable dataset to meet the needs. According to the dataset and the base net, we summarize and compare the method table form and discuss the research results. Finally, we analyze the research direction that can be promoted and provide a reference for researchers who pay attention to this field.

In conclusion, semantic segmentation on domain adaptation has achieved a lot of success, and its solution has been proved to be very useful in application to the real world, but there is still a lot of room for improvement. We are looking forward to more innovations in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z. and Q.T.; formal analysis, L.M. and S.H.; investigation, L.D.; resources, X.L.; data curation, N.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z.; writing—review and editing, Q.T.; visualization, L.D. and S.H.; supervision, L.M.; funding acquisition, N.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the R & D and Application Demonstration of Trustworthy Multimodal Large Models for Industrial Situation Awareness and Decision-Making, grant number Z241100001324010.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UDA | Unsupervised Domain Adaptation |

| VLM | Vision-Language Model |

| VL | Vision-Language |

| RPT | Regularizer of Prediction Transfer |

| SIM | Stuff and Instance Matching |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| PFA | Progressive Feature Alignment |

| SGG | Semantic Gradient Guidance |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| SSL | Semantic Segmentation Learning |

| DS | Domain Stylization |

| CIR | Content Invariant Representation |

| ACM | Ancillary Classifier Module |

| ETM | Expanding Target-Specific Memory |

| TM | Target-Specific Memory |

| CyCADA | Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Domain Adaptation |

| CCM | Content-Consistent Matching |

| PyCDA | Pyramid Curriculum Domain Adaptation |

| SSDDA | Semi-Supervised Dual-Domain Adaptation |

| RPLR | Reliable Pseudo-Label Retraining |

| SAC | Self-Supervised Augmentation Consistency |

| DPL | Dual Path Learning |

| CBST | Class-Balanced Self-Training |

| CRST | Confidence Regularized Self-Training |

| MIoU | Mean Intersection over Union |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| GTAV | Grand Theft Auto V |

References

- Nikolenko, S.I. Synthetic Data for Deep Learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.11512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Lyu, M.R.; King, I.; Xu, J. SelFlow: Self-Supervised Learning of Optical Flow. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 4566–4575. [Google Scholar]

- Dundar, A.; Liu, M.Y.; Wang, T.C.; Zedlewski, J.; Kautz, J. Domain Stylization: A Strong, Simple Baseline for Synthetic to Real Image Domain Adaptation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.09384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.H.; Hung, W.C.; Schulter, S.; Sohn, K.; Yang, M.H.; Chandraker, M.K. Learning to Adapt Structured Output Space for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 7472–7481. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolet, B.; Philip, J.; Drettakis, G. Repurposing a Relighting Network for Realistic Compositions of Captured Scenes. In Proceedings of the I3D ’20: Symposium on Interactive 3D Graphics and Games, San Francisco, CA, USA, 15–17 September 2020; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, C.; Cham, T.J.; Cai, J. T2Net: Synthetic-to-Realistic Translation for Solving Single-Image Depth Estimation Tasks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.01454. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Huang, J.B.; Yang, X.; Yang, M.H. Hierarchical Convolutional Features for Visual Tracking. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 3074–3082. [Google Scholar]

- Cordts, M.; Omran, M.; Ramos, S.; Rehfeld, T.; Enzweiler, M.; Benenson, R.; Franke, U.; Roth, S.; Schiele, B. The Cityscapes Dataset for Semantic Urban Scene Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 3213–3223. [Google Scholar]

- Brostow, G.J.; Fauqueur, J.; Cipolla, R. Semantic object classes in video: A high-definition ground truth database. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2009, 30, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, S.R.; Vineet, V.; Roth, S.; Koltun, V. Playing for Data: Ground Truth from Computer Games. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1608.02192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.J.; Yang, Q. A Survey on Transfer Learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2010, 22, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.; Zhu, H.; Wang, J.; Jordan, M.I. Deep Transfer Learning with Joint Adaptation Networks. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2017, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; Volume 70, pp. 2208–2217. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, J.; Tzeng, E.; Darrell, T.; Saenko, K. Simultaneous Deep Transfer Across Domains and Tasks. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 4068–4076. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.Y.; Tuzel, O. Coupled Generative Adversarial Networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.07536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousmalis, K.; Silberman, N.; Dohan, D.; Erhan, D.; Krishnan, D. Unsupervised Pixel-Level Domain Adaptation with Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Bousmalis, K.; Trigeorgis, G.; Silberman, N.; Krishnan, D.; Erhan, D. Domain Separation Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 29: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 5–10 December 2016; pp. 343–351. [Google Scholar]

- Ghifary, M.; Kleijn, W.B.; Zhang, M.; Balduzzi, D.; Li, W. Deep Reconstruction-Classification Networks for Unsupervised Domain Adaptation. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision-ECCV 2016-14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Volume 9908, pp. 597–613. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer, L.; Dai, D.; Van Gool, L. Domain Adaptive and Generalizable Network Architectures and Training Strategies for Semantic Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. PAMI 2024, 46, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Sun, F.; Kong, T.; Zhang, W.; Yang, C.; Liu, C. A Survey on Deep Transfer Learning. In Proceedings of the Artificial Neural Networks and Machine Learning—ICANN 2018—27th International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, Rhodes, Greece, 4–7 October 2018; Volume 11141, pp. 270–279. [Google Scholar]

- Csurka, G. Domain Adaptation for Visual Applications: A Comprehensive Survey. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1702.05374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; David, P.; Foroosh, H.; Gong, B. A Curriculum Domain Adaptation Approach to the Semantic Segmentation of Urban Scenes. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 42, 1823–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, F.; Qi, Z.; Duan, K.; Xi, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Xiong, H.; He, Q. A Comprehensive Survey on Transfer Learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.02685v3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Chen, L. A Survey on Open-Vocabulary Detection and Segmentation: Past, Present, and Future. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 46, 8954–8975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Deng, W. Deep visual domain adaptation: A survey. Neurocomputing 2018, 312, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]