Abstract

This paper examines the relationship between weak orthogonality and almost orthogonality for complete non-algebraic 1-types in weakly ordered minimal theories. A central element of our approach is the concept of neighborhoods, which encapsulate local properties of type realizations. This work contributes to a deeper understanding of the geometry of types in weakly ordered minimal theories and provides tools that may be applied in related model-theoretic contexts.

Keywords:

weakly o-minimal theories; weak orthogonality; almost orthogonality; convex set; quasisolitary type; quasirational type; irrational type MSC:

03C64

1. Introduction

This paper investigates weak orthogonality and almost orthogonality in the context of weakly ordered minimal structures. Recall that ordered minimality, introduced in Van den Dries’ work [1], provides a setting in which every definable subset of the domain is a finite union of points and intervals. Weak ordered minimality relaxes this condition by allowing definable subsets to be finite unions of convex sets, a concept introduced by Dickmann [2]. In the study of weak o-minimality, the work of Macpherson, Marker, and Steinhorn [3] was especially important, as it laid the basis for later research on minimality and its applications.

Our focus is on the interaction between non-algebraic complete 1-types. A key tool in our analysis is the study of neighborhoods, which capture local information about realizations of types.

The techniques used in this paper have also been applied in related contexts, such as expansion by unary externally definable predicates, and in the study of conservative extensions and type definability in weakly o-minimal theories.

The notions of orthogonality and almost orthogonality played a significant role in [4]. Furthermore, orthogonality plays an important role in counting countable models, as shown in the work of L. Mayer [5] and in later contributions in [6,7,8].

Our main results characterize the precise relationship between weak and almost orthogonality in for weakly ordered minimal theories, and provide criteria for their equivalence. We also describe how these notions behave for specific classes of types, such as rational, irrational, solitary, and quasisolitary.

In contrast to the study of expansions, where quasi-neighborhoods play the central role, the investigation of orthogonality focuses on neighborhoods. Orthogonality has been extended to convex orthogonality for incomplete 1-types. In [9], convex orthogonality is considered for the convex closure of a complete type. The results obtained here complement those of [10].

Our results expand upon the framework introduced in an unpublished preprint, completing and extending several of its central arguments.

2. Preliminaries

We adhere to the following convention throughout.

Let with and , we write to mean . Let , then .

Throughout, is a model of a weakly o-minimal theory T, and is a sufficiently large saturated elementary extension of , the Latin letters denote elements of : , , , , while the Greek letters denote elements of : , , , .

For any , we write if whenever , . For , we write if .

For any set

If with , write . Note that .

We use for inclusion, i.e., whenever implies , and for proper inclusion, i.e., if if and .

Whenever a set of parameters is fixed, we assume that is -saturated.

Types will always be non-algebraic complete 1-types over A. By an isolated type, we mean a non-algebraic isolated type.

is the group of all automorphisms of that fix A pointwise, that is, for any and any .

We use the following notations:

Definition 1.

Let A be a linearly ordered set, and . We say that B is convex if, for all , and all ,

Definition 2.

We say that a formula , with , is convex to the right if

We say that a formula , with , is convex to the left if

Definition 3

(Baizhanov B.S., Verbovskii V.V., [11]). 1. The convex closure of a formula is the following formula:

- 2.

- The convex closure of a type is the following type:

Definition 4

(Baizhanov B.S., [12]). Let . We say that a formula , with , is p-stable (p-preserving) if

Other recent studies explore formulas from different perspectives, including partial clones of linear formulas [13] and superassociative structures [14].

Definition 5

(Marker D. [15]). A cut is uniquely realizable over if and only if, for any c realizing , c is the only realization of in the prime model .

Following Marker’s notion of uniquely realizable types, we generalize this concept to the context of weakly o-minimal theories and refer to such types as solitary.

Definition 6

(Baizhanov B.S. [10]). Let be a non-algebraic type.

We say that p is semi-quasisolitary to the right if there exists the greatest p-preserving convex to the right 2-A-formula , where .

We say that p is semi-quasisolitary to the left if there exists the greatest p-preserving convex to the left 2-A-formula , where .

We say that p is quasisolitary if it is semi-quasisolitary to the right and to the left.

Let be the greatest convex to the right p-preserving formula, and is the greatest convex to the left p-preserving formula. It was proved in [16] that the formula is an equivalence relation.

Let be quasisolitary. We say that p is solitary if .

Definition 7

([16]). A type is social if there exists no greatest convex to the right (equivalently, convex to the left) on p formula.

Definition 8

([17]). A partition of into two convex subsets C and D, such that , is said to be a cut in A. If C has a supremum or D has an infimum in , then the cut is said to be rational.

Definition 9

([10]). Let be non-isolated. We say that p is quasirational to the right if there exists a formula with such that, for any the following is true:

We say that p is quasirational to the left if there exists a formula with such that, for any the following is true:

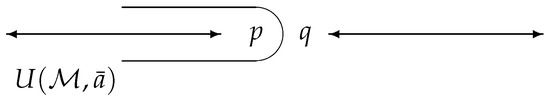

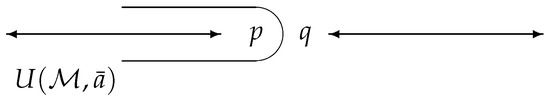

A non-isolated, non-quasirational type p is said to be irrational (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

p is a quasirational to the right type and q is a quasirational to the left type.

Remark 1

([16]). 1. If T is o-minimal, then each quasisolitary type is solitary (uniquely realizable [Laskovski M., Steinhorn Ch., [18]).

- 2.

- There exist the following six essential kinds of non-algebraic 1-types over sets of models with a weakly o-minimal theory:

- (1–2)

- isolated (quasisolitary, social);

- (3–4)

- quasirational (quasisolitary, social);

- (5–6)

- irrational (quasisolitary, social).

Definition 10.

Let , such that is -saturated. Then a neighborhood of a set B in the type p is the following set:

This definition adapts the notion of neighborhoods, which was introduced in the context of semi-isolation.

3. Results

Proposition 1.

Let .

- (i)

- Let . Then if and only if p is solitary.

- (ii)

- p is quasisolitary if and only if there exists , and is -definable set. (In fact

Proof.

(i) (⇒) Let p be a solitary type. It follows that, , which means that for every , the equivalence class under contains only one element: itself. Since is defined as the equivalence class of under , if p is solitary, then

- (⇐)

- Suppose , then identifies only trivial equivalences. Consequently, , and p is solitary.

- (ii)

- The neighborhood is defined as the equivalence class of under , i.e.,:

- (⇒)

- Let , then there exists a formula such that . LetSince is convex . Notice thatThen On the other hand, by definition, . Hence, .

- (⇐)

- Assume that for some , the set is -definable. That is, there exists a formula such thatMoreover, since is an equivalence class under , it is convex and contained in . Define the formula as follows:Then defines an equivalence relation on with convex classes, and for the fixed , we have:Therefore, p is quasisolitary.

□

Lemma 1.

Proof.

We know that if then for every formula it holds that Now consider an automorphism f of fixing A such that , .

It is clear that , consequently . Therefore, there exists such that .

Suppose . Then there exists a formula and elements such that:

If then . Thus, the formula serves as a witness to the fact that , since for any the formula fails at (such that □

Theorem 1

(Compactness Theorem, Henkin L. [19]). If every finite subset of a set T of L-sentences is satisfiable, then T itself is satisfiable.

Lemma 2.

1. Let be non-algebraic, , and let , where , be such that (that is, p isolates q).

- 2.

- If q is irrational to the left, then there is no M-definable formula with and for any formula , where , with , there exists such that

- 3.

- If q is irrational to the right, that is, there does not exist an M-definable formula with then for any formula , where , with , there exists such that

Proof.

1. Let be non-algebraic types, , and let be a formula with parameters such that (p isolates q). Let

Fix any formula , and define the formula

Since then

- 2.

- Let be irrational to the left. We claim that there is no M-definable formula such that Suppose there is such formula , then is consistent because for any finite set of formulasThus, there is a realization of contradicting the assumption.Let be any formula with parameters . This implies that for every , there is an element such thatOtherwise would be bounded below inside , contradicting the irrationality of q to the left. Thus, the setis consistent, and therefore there exists some such that

- 3.

- Let be irrational to the right. We claim that there is no -definable formula such thatSuppose such a formula exists. Then the set is consistent because for any finite set of formulas , we haveThus, there is a realization of , which contradicts the assumption that q is irrational to the right.Let be any formula with parameters . This implies that for every , there is an element such thatOtherwise, would be bounded above inside , contradicting the irrationality of q to the right. Thus, the setis consistent, yielding some such that such that .

□

Theorem 2.

Let , such that M is -saturated. Then the following holds:

- (i)

- is convex or empty.

- (ii)

- Let p be irrational. Then , for any formula

- (iii)

- (iv)

- (v)

Proof.

(i) By Definition 10.

- (ii)

- By Definition 10 and by Lemma 2 (ii), (iii).

- (iii)

- By Definition 10 and by Compactness Theorem (Theorem 1).

- (iv)

- Suppose that there exists such that . Then there exists , with , and there is , with , such thatBy Definition 10 there are such thatLet , , be such that . Define , . Thenand either or . Now letThen , while . Let be a convex subformula of such that ThusThen and . Which is a contradiction.

- (v)

- Assume .

- Step 1.

- We are going to show that . Suppose for contradiction that and are not disjoint sets . Let andPick some . DefineSince , with , and , it follows that .This is a contradiction, because we assumed . Hence, we conclude that .

- Step 2.

- Now we will show that .

- (a)

- is definable.

- (a1)

- is definable.Let be the right border of the neighborhood .Since , then .

- (a2)

- The neighborhood isThe set of formulasis consistent, and consequently there is that satisfies the set. Then

- (b)

- is non-definable. Since by Step 1 , then the lower bound of is non-definable. The set of formulasis consistent. Therefore, there is an element that satisfies the set.

□

We will use notations analogous to those in Stability Theory [20,21].

Definition 11.

If p is not weakly orthogonal to q, we will denote this fact by .

Let . We say that p is weakly orthogonal to q () if for any , with , for any , the following holds:

Lemma 3.

(i) .

- (ii)

- is a complete 2-A-type.

- (iii)

- If p is algebraic, then for every , it follows that .

Proof.

(i) Assume . Then there exist an A–formula , some , and there are such that

- Assume . Since satisfies , then Let us define the following set of formulas:satisfies . Thenis consistent and closed over finite conjunction. Since for any finiteThere is some that satisfies the setSince , then . Therefore, .In general the weak orthogonality relation is symmetric.

- (ii)

- (⇒)

- Assume , and let , . Then for any A-formula , for any and anyIf there exists a realization of q such that holds, then by weak orthogonality every realization of q also must satisfy . Consequently, for every pair we haveTherefore,Since was arbitrary, decides every A-formula in the variables . Thus is a complete 2-A-type.

- (⇐)

- Assume that is a complete 2-A-type.Let , and let be any –formula. Suppose Let with . By completeness of applied to the formula we haveThe second alternative cannot hold, since , , and . HenceTherefore, for every we have , i.e.,Since and were arbitrary, this is exactly the definition of .

- (iii)

- Let p is algebraic over A. Then there is an A-formula whose set of solutions is exactly . Then , and .Let suppose there are such that . Thenisolates exactly one element.Suppose there is in p such that in q.Since x is singular then it is consistent thatSince the formulas are mutually contradictory, they cannot be used together. Therefore, .

□

Definition 12.

Let . We say that p is almost orthogonal to q (), if (), and . If p is not almost orthogonal to q, then we denote this fact by .

From this definition if and only if . And there is a formula such that there are ,

Lemma 4.

Let . Then the following propositions are true:

- (i)

- .

- (ii)

- There exists T — a weakly o-minimal theory such that , and .

- (iii)

- Let T be o-minimal. Then .

Proof.

(i) Assume . By the definition of weak orthogonality, for every A-definable formula and every ,

- By the definition of the neighborhood , there exist and an A-definable formula such thatIn particular, but (since lie outside the convex set ). This contradicts (1).Hence for (some hence all) , which is exactly by the definition of almost orthogonality.

- (ii)

- Let consider , and .Let is a binary relation such thatThe theory of this structure has quantifier elimination. Let us define non-algebraic 1-typesThus, , since for an arbitrary the set and the set are both consistent.Let consider an authomorphism f such that , and .Since we do not have any formula in that type, then . Therefore, .

- (iii)

- (⇒)

- Since by (i) in any theory, then it is true for o-minimal theories.

- (⇐)

- Assume . We must show that . Let be any A-definable formula and let . SupposeSet . By o-minimality, S is a finite union of points and open intervals; Hence it is a finite union of convex sets. Since is convex, the intersection is again a finite union of convex subsets of .We claim that . Suppose not. Then there exists a nonempty convex component which is a proper subset of . Because is convex, we can choose withBut , soBy the definition of the neighborhood , this implies , contradicting . Hence, the assumption was false, and we must have .Since , and were arbitrary, we have shown that for every A-definable and every ,which is exactly by definition.

□

The following example illustrates that that the inverse of Lemma 4 (i) does not hold.

Example 1.

And let if and only if .

Let , where U is a binary predicate, < is the standard relation of dense linear order without endpoints, for all , from and all from , and

Define , and . The types p and q are distinct non-isolated types over the empty set. Let be an arbitrary model of realizing the type p. For each the set is a convex set such that , , and . Moreover, there is no ∅-definable formula such that is a proper subset of . Then , but .

Theorem 3.

Let . Then the following propositions are true:

- (1)

- Let . If p is social, then q is social, and .

- (2)

- .

- (3)

- is a relation of equivalence on .

- (4)

- is a relation of equivalence on .

In proof of the theorem:

- (1)

- We will use Lemma 5, Remark 2, Lemmas 6 and 7, and Remark 3.

- (2)

- Follows from the Lemma 5.

- (3)

- We already know that is reflexive and symmetric. We are going to show that is transitive relation using Lemma 8, Remark 4, and Theorem 2.

- (4)

- We already know that is reflexive and symmetric (Note 3). We are going to show that is transitive relation using Lemma 7, Remark 3.

Proof.

Clearly,

Since T is weakly o-minimal, , , is a union of convex -separable subsets, there are , is the maximal convex -definable subset such that

Consider the following formula:

It follows that,

It follows from Lemma 2 (ii) that if q is quasirational to the left or isolated, then there exists a 1-A-formula , with such that

Let

It is clear that

This contradicts the fact that .

Consider arbitrary , then ,

For , there exists such that . By Remark 2, we then have This leads to a contradiction, since . Therefore,

Then suppose that for any

Thus,

Then

Hence, Lemma 8 is proved.

It follows that:

By a similar consideration of the formula

we obtain a formula such that and

Suppose and with . Let be the maximal convex subformula of such that . Then, . For there is such that . Hence, we have Consider the formula

(1) Consider two cases:

- (a)

- ,

- (b)

- , and .

Lemma 5(Claim 37 in [16]). Let p isolate q by a formula , with , such that there exist and there are , , such that , and . Then there exists a formula such that for all there exist , such thatand p is quasisolitary if and only if q is quasisolitary.If , then by Lemma 5, if p is social, then q is social.Consider the case , . We can construct the 2-A-formula , with such that for any , both , and are convex,

Remark 2.

Let . Consider , such that . Then

Lemma 6.

Let .

- (i)

- If , , then if and only if if and only if if and only if .

- (ii)

- If such that , , then or .

Proof of Lemma 6

- (i)

- This is an immediate corollary of the proof of Theorem 2 (iv).

- (ii)

- By Theorem 2 (iv), the following is true:ThenSuppose there is such that . Let , with be a formula such that . Consider the following formula:Then , while . Consequently, . Which is a contradiction. Consideration of other cases are the same. Hence, Lemma 6 is proved.

Lemma 7.

If (respectively, ) then for any (respectively, ), with , . And there exists , with , (respectively, ) such that

Proof of Lemma 7

We suppose that , a consideration of the case is the same. Let , then

Suppose there exists , with , and .

Consider three -definable sets:

Consider three cases:

We have two possibilities for p:

- a.

- p is irrational to the left. Then there exists , with , such that

- b.

- p is quasirational to the left. Then there exists , with , such that

Thus, we obtain:

Then and . Which is a contradiction.

Then there is — maximal -definable subset of such that

Let

If such that , then . This contradicts . Thus

Notice that .

Consider an arbitrary , then and Then

i = 3.

Then there is — maximal -definable subset of such that

Let So,

If , then . Contradiction with .

Thus It follows from Lemma 2 (ii) that if q is quasirational to the left or isolated. Then there is a 1-A-formula , with such that

Let

It follows that is the maximal -definable subset of . Clearly, is the required formula. Hence, Lemma 7 is proved.

Let . Then, is maximal convex to the left p-stable 2-A-formula. This implies that p is quasisolitary. Consequently, if p is social and , then . By Lemma 5 it follows that q is social.

Remark 3.

Let , and . Then the following hold:

- (i)

- If then .

- (ii)

- If , and then

- (iii)

- If , and such that then

- (2)

- follows from Lemma 5.

- (3)

- for any by Definition 12. If then by Lemma 3 (ii). Suppose , and .

Lemma 8.

Let , , , such that . Then for any , for any , with such that for the formula the following is true:

Proof of Lemma 8

By Lemma 6 (ii), for any

Remark 4.

Let , and , and such that M is -saturated.

- (i)

- If , with then for such that the following is true:

- (ii)

- For every , and for every type , with the following is true:

Consider , then because . By Remark 4 (i) and Theorem 2 (iii) . Then, .

- (4)

- for any by Definition 1. If then by Note 3 (i). Suppose , , and . Thus, by Theorem 3 (ii), p and q are quasisolitary. Let be a formula from Lemma 7. Then from Remark 3 (ii), it follows:Let . If there exists such that , andthen for any

Without loss of generality suppose that is increasing on classes of equivalence of elements from . Consider the following formula:

If p is quasirational to the left then there exists such that .

If p is non-quasirational to the left, then there is such that

Let . Then there is the formula such that

Therefore, , because . Moreover, , since . Thus, . Hence, Theorem 3 is proved. □

Corollary 1.

The equivalence relations and partition the set of non-algebraic types from into the classes of equivalence as follows:

- (i)

- Every -class contains -classes or it coincides with a -class.

- (ii)

- Every -class contains types only of one kind from six basic kinds of Remark 1.

- (iii)

- Every -class, which contains social types, is a -class.

Lemma 9

the following is true

([16]). Let , and is p-stable formula where . There is , with and there are , such that Then there are , from such that for the formula

Theorem 4.

Let such that M is -saturated, , and . Then the following hold:

- (i)

- If , then if and only if .

- (ii)

- If , , , then there exists such that

- (iii)

- If , and there is such that , then

Proof.

Then for any , we have

Thus, there exist such that Suppose . Let us define

Then there are such that

because there are such that

Thus, since there is such that

Consider the formula

The existence of these follows from proof of (ii). Let be such that and . Suppose . Then . If , then there is , with , and such that . Consider the following formula:

We then have

(i) It follows from Lemma 8 and Remark 4 (ii).

(ii) Let be a formula from Lemma 7, which was obtained from the fact , and , such that the following hold:

Without loss of generality, as in the proof of Lemma 7, we suppose:

Suppose , for all .

Let . Then there are two formulas , and , with such that and there are such that

Consider the formula .

Because is p-stable, Lemma 9 guarantees the existence of of such that . Moreover, for every , it follows that . Let

Then by the same consideration as for . Thus, . Which is a contradiction.

Thus, such that . For quasisolitary type q, . Hence, (ii) is proved.

(iii) By Theorem 2 (v), we have where , , and

Thus, , and .

Suppose . Then . If , then there is , with , and such that . Consider the following formula:

Thus, if , then , and consequently . This yields a contradiction. Hence,

□

4. Discussion

The main result of this work is the unification of the concepts of type orthogonality and neighborhoods in a type. It can be observed that the notion of a neighborhood of an element within a type generalizes the idea of algebraic closure in a type.

The concept of orthogonality, originally introduced by Shelah S. in [22], is further refined here. In particular, semi-isolation between 1-types splits into two distinct notions: weak orthogonality and almost orthogonality for weakly o-minimal theories.

This paper establishes the connection between p-stable (p-preserving) types and neighborhoods, highlighting how local type behavior can be captured through neighborhood analysis.

The orthogonality properties of types in weakly o-minimal theories, as explored in this article, can be extended to the broader class of NIP theories. In particular, the foundations for this extension, including the notion of ordered stable theories (o-stable theories), were established in works [9,11,23].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B.; Formal analysis, B.B., N.T. and T.Z.; Funding acquisition, B.B.; Methodology, B.B. and N.T.; Supervision, B.B.; Validation, B.B., N.T. and T.Z.; Writing—original draft, B.B. and N.T.; Writing—review and editing, B.B., N.T. and T.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP19677434).

Data Availability Statement

The materials supporting this study are provided in the article. For any additional questions, please contact the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- van den Dries, L. Remarks on Tarski’s problem concerning . In Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickmann, M.A. Elimination of quantifiers for ordered valuation rings. In Proceedings of the 3rd Easter Model Theory Conference, Gross Koris, Germany, 8–13 April 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson, D.; Marker, D.; Steinhorn, C. Weakly o-minimal structures and real closed fields. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 2000, 352, 5435–5483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marker, D.; Steinhorn, C. Definable types in o-minimal theories. J. Symb. Log. 1994, 59, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, L. Vaught’s conjecture for o-minimal theories. J. Symb. Log. 1988, 53, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibek, A.; Baizhanov, B.S.; Kulpeshov, B.S.; Zambarnaya, T.S. Vaught’s conjecture for weakly o-minimal theories of convexity rank 1. Ann. Pure Appl. Log. 2018, 169, 1190–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulpeshov, B.S. Vaught’s conjecture for weakly o-minimal theories of finite convexity rank. Izv. Math. 2020, 84, 324–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulpeshov, B.S.; Sudoplatov, S.V. Vaught’s conjecture for quite o-minimal theories. Ann. Pure Appl. Log. 2017, 168, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baizhanov, B.; Umbetbayev, O.; Zambarnaya, T. Non-orthogonality of 1-types in theories with a linear order. Bull. Irkutsk. State Univ. Ser. Math. 2025, 53, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baizhanov, B.S. Orthogonality of one-types in weakly o-minimal theories. In Algebra and Model Theory; Pinus, A.C., Ponomaryov, K.N., Eds.; Novosibirsk State Technical University: Novosibirsk, Russia, 1999; pp. 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Baizhanov, B.S.; Verbovskii, V.V. O-stable theories. Algebra Log. 2011, 50, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baizhanov, B.S. One-Types in Weakly O-Minimal Theories; Informatics and Control Problems Institute: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 1996; pp. 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Denecke, K. The Partial Clone of Linear Formulas. Sib. Math. J. 2019, 60, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumduang, T.; Sriwongsa, S. Superassociative structures of terms and formulas defined by transformations preserving a partition. Commun. Algebra 2023, 51, 3203–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marker, D. Omitting types in o-minimal theories. J. Symb. Log. 1986, 51, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baizhanov, B.S.; Tazabekova, N.S. Essential kinds of 1-types over sets of models of weakly o-minimal theories. Kazakh Math. J. 2023, 23, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascar, D.; Poizat, B. An introduction to forking. J. Symb. Log. 1979, 44, 330–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskovski, M.; Steinhorn, C. On o-minimal expansions of Archimedean ordered groups. J. Symb. Log. 1995, 60, 817–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkin, L. The completeness of the first-order functional calculus. J. Symb. Log. 1949, 14, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelah, S. Classification Theory and the Number of Non-Isomorphic Models; North Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, J. Fundamentals of Stability Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Shelah, S. Classification Theory and the Number of Non-Isomorphic Models; Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics; North-Holland Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; New York, NY, USA; Oxford, UK, 1990; Volume 92, p. xxxiv + 705. [Google Scholar]

- Verbovskiy, V. On a classification of theories without the independence property. Math. Log. Q. 2013, 59, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).